Difference between revisions of "Greek philosophy, Ancient" - New World Encyclopedia

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) |

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

[[Archelaus (philosopher)|Archelaus]] was a Greek philosopher of the 5th century B.C.E., born probably in Athens, though Diogenes Laërtius (ii. 16) says in Miletus. He was a pupil of Anaxagoras, and is said by Ion of Chios (Diogenes Laërtius, ii. 23) to have been the teacher of Socrates. Some argue that this is probably only an attempt to connect Socrates with the Ionian School; others (e.g. Gomperz, Greek Thinkers) uphold the story. There is similar difference of opinion as regards the statement that Archelaus formulated certain ethical doctrines. In general, he followed Anaxagoras, but in his cosmology he went back to the earlier Ionians. | [[Archelaus (philosopher)|Archelaus]] was a Greek philosopher of the 5th century B.C.E., born probably in Athens, though Diogenes Laërtius (ii. 16) says in Miletus. He was a pupil of Anaxagoras, and is said by Ion of Chios (Diogenes Laërtius, ii. 23) to have been the teacher of Socrates. Some argue that this is probably only an attempt to connect Socrates with the Ionian School; others (e.g. Gomperz, Greek Thinkers) uphold the story. There is similar difference of opinion as regards the statement that Archelaus formulated certain ethical doctrines. In general, he followed Anaxagoras, but in his cosmology he went back to the earlier Ionians. | ||

| − | === | + | ===[[Pythagoras]] and [[Pythagoreans]]=== |

| − | + | '''Pythagoras''' (c. 570 B.C.E.-496 B.C.E.), [[Greek language|Greek]]: | |

| + | Πυθαγόρας) was a [[mystic]], and a [[mathematician]], known best for the [[Pythagorean theorem]]. | ||

| − | + | The earliest Greek philosophers in [[Ionia]], known as the [[Ionians]], such as [[Thales]], [[Anaximander]], and [[Anaximenes]], explored the origin of existing beings and developed theories of nature in order to explain the natural processes of the formation of the world. Pythagoras, who was born on an island off the coast of Ionia and later moved to Southern Italy, explored the question of the salvation of human beings by clarifying the essence of existing beings, and developing a mystical religious philosophy. Pythagoras developed both a theoretical foundation and a practical methodology, and formed an ascetic religious community. Followers of Pythagoras are known as Pythagoreans. | |

| + | |||

| + | Pythagoras approached the question of being from an angle that was different from that of early Ionian philosophers. While the Ionians tried to find the original matter out of which the world is made, Pythagoras dove into the principles that give order and harmony to the elements of the world. In other words, Pythagoras found the essence of being not in “what is to be determined” but in “what determines.” From Pythagoras’ perspective, the Ionians’ prime elements, such as Thales’ “water” and Anaximander’s “indefinite,” were beings that were equally determined, and they did not explain why and how the world was orderly structured and maintained its rhythm and harmony. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to Pythagoras, “[[number]]” or mathematical principle was that which gives order, harmony, rhythm, and beauty to the world. This harmony keeps a balance both in the cosmos and in the soul. For Pythagoras, “numbers” are not abstract concepts but embodied entities manifested as norms, cosmos, and sensible natural objects. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The mathematical order in beings is perceivable not by the physical senses but by senses of the soul. Unlike the modern concept of mathematical exercises, Pythagoras conceived mathematics as the method for liberating the soul from the bondages of bodily senses and essentially as religious training. For Pythagoras, the soul is [[Immortality of the soul|immortal]]* and the cultivation of the soul is achieved by the studies of truth and the ascetic life. Aristotle noted that Pythagoras was the first person who took up the issue of “[[virtue]]” in philosophy (DK. 58B4). | ||

| + | Pythagoras opened a new path to early Greek [[ontology]] by his focus on the soul, virtue, and the ascetic life. He presented a new integral model of thought where the mystic and the mathematical or the religious and the scientific (as well as the aesthetic) are uniquely integrated. This type of thought is uncommon in mainstream philosophy today. Like other wise men of antiquity, Pythagoras had a broad knowledge encompassing medicine, music, cosmology, astronomy, mathematics and others. Finally, his thought made a strong impact on [[Plato]] which is seen through his works. | ||

===[[Parmenides]] and the other [[Eleatic]] philosophers=== | ===[[Parmenides]] and the other [[Eleatic]] philosophers=== | ||

| Line 69: | Line 77: | ||

===[[Leucippus]], [[Democritus]] and the other [[atomism|Atomists]]=== | ===[[Leucippus]], [[Democritus]] and the other [[atomism|Atomists]]=== | ||

| + | '''Leucippus''' or '''Leukippos''' ([[Greek language|Greek:]] {{Polytonic|Λεύκιππος}}, first half of [[5th century B.C.E.]]) was among the earliest philosophers of [[atomism]], the idea that everything is composed entirely of various imperishable, indivisible elements called [[atom]]s. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Democritus''' ([[Greek language|Greek]]: {{Polytonic|Δημόκριτος}}) was a [[The Presocratics|pre-Socratic]] [[Hellenic civilization|Greek]] [[philosopher]] (born at [[Abdera, Thrace|Abdera]] in [[Thrace]] ca. [[460 B.C.E.]] - died ca [[370 B.C.E.]]).<ref>''Encyclopedia Britannica''. [http://www.britannica.com/ebc/article-9362512 Democritus]. Retrieved 2006-10-21.</ref><ref>''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy''. [http://www.iep.utm.edu/d/democrit.htm Democritus]. Retrieved 2006-08-01.</ref> Democritus was a student of [[Leucippus]] and co-originator of the belief that all [[matter]] is made up of various imperishable, indivisible [[Classical element#Classical elements in Greece|elements]] which he called ''atoma'' (sg. ''atomon'') or "indivisible units", from which we get the English word [[Atomism|atom]]. It is virtually impossible to tell which of these ideas were unique to Democritus and which are attributable to Leucippus. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===[[Sophists]]=== | ||

| + | The Greek words [[sophos]] or [[sophia]] had the meaning of "wise" or "wisdom" since the time of the poet [[Homer]], and originally connoted anyone with expertise in a specific domain of knowledge or craft. Thus a charioteer, a sculptor, a warrior could be [[sophoi]] in their occupation. Gradually the word came to denote general wisdom (such as possessed by the [[Seven Sages of Greece]]), this is the meaning that appears in the histories of Herodotus. At about the same time, the term [[sophistes]] was a synonym for "poet", and (by association with the traditional role of poets as the teachers of society) a synonym for one who teaches, especially by writing prose works or speeches that impart practical knowledge. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the second half of the 5th century B.C.E., and especially at [[Athens]], "sophist" came to denote a class of itinerant intellectuals who employed [[rhetoric]] to achieve their purposes, generally to persuade or convince others. Most of these sophists are known today primarily through the writings of their opponents (specifically [[Plato]] and [[Aristotle]]), which makes it difficult to assemble an unbiased view of their practices and beliefs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Many of them taught their skills, apparently often for a fee. Due to the importance of such skills in the litigious social life of Athens, practitioners of such skills often commanded very high fees. The practice of taking fees, coupled with the willingness of many sophists to use their rhetorical skills to pursue unjust [[lawsuit]]s, eventually led to a decline in respect for practitioners of this form of teaching and the ideas and writings associated with it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Protagoras]] is generally regarded as the first of these sophists. Others included [[Gorgias]], [[Prodicus]], [[Hippias]], [[Thrasymachus]], [[Lycophron]], [[Callicles]], [[Antiphon (person)|Antiphon]], and [[Cratylus]]. | ||

| − | + | In Plato's dialogs, [[Socrates]] challenged their [[moral relativism]] by arguing the eternal existence of truth. | |

===[[Empedocles]]=== | ===[[Empedocles]]=== | ||

| Line 126: | Line 146: | ||

[[Category:philosophy and religion]] | [[Category:philosophy and religion]] | ||

| − | {{Credits|Greek_philosophy|103276965|Ionian_School|157957942|Eleatics|148313093|}} | + | {{Credits|Greek_philosophy|103276965|Ionian_School|157957942|Eleatics|148313093|Leucippus|164855315|Democritus|168238813|Sophism|168453635}} |

Revision as of 01:47, 2 November 2007

Ancient Western philosophy designates the philosophy from around the sixth century B.C.E. to the sixth century C.E.. This period became important because of three great thinkers, Socrates (fifth century B.C.E.), his student Plato (fourth century B.C.E.), and Plato's student Aristotle (fourth century B.C.E.). They laid the foundation of Western philosophy by exploring and defining the range, scope, method, terminology, and problematics of philosophical inquiry.

Ancient Western philosophy is generally divided into three periods centering on them: the fist, the period prior to Socrates, all thinkers prior to Socrates are called PreSocratics; second, the period of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle; and the last, the period that covers diverse philosophy after them, which includes Stoics, Epicureans, Skeptics in Hellenistic age, and Neo-Platonists, Aristotelians under Roman Empire. Spread of christianity ushered the end of Ancient Philosophy in the sixth century C.E.

Pre-Socratic philosophers

Greek philosophers prior to Socrates are called Pre-Socratics or pre-Socratic philosophers. They were the earliest Western philosophers, active during the fifth and sixth centuries B.C.E. in ancient Greece. These philosophers tried to discover original principles (arkhế; ἀρχή; the origin or the beginning) that could uniformly, consistently, and comprehensively explain all natural phenomena and the events in human life without resorting to mythology. They initiated a new method of explanation known as philosophy which has continued in use until the present day, and developed their thoughts primarily within the framework of cosmology and cosmogony.

Socrates was a pivotal philosopher who shifted the central focus of philosophy from cosmology to ethics and morality. Although some of these earlier philosophers were contemporary with, or even younger than Socrates, they were considered pre-Socratics (or early Greek Philosophers) according to the classification defined by Aristotle. The term "Pre-Socratics" became standard since H. Diels' (1848 - 1922) publication of Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, the standard collection of fragments of pre-Socratics.

It is assumed that there were rich philosophical components in religious traditions of Judaism and Ancient Egyptian cultures, and some continuity of thought from these earlier traditions to pre-Socratics is also assumed. Although we do not have much information sources about their continuity, Proclus, fifth century Neo-Platonist, for example, noted that the earliest philosophy such as Thales studied geometry in Egypt.

The pre-Socratic style of thought is often called natural philosophy, but their concept of nature was much broader than ours, encompassing spiritual and mythical as well as aesthetic and physical elements. They brought human thought to a new level of abstraction; raised a number of central questions of ontology, which are still relevant today; and cultivated the human spirit so as to open our eyes to the eternal truth. Primary sources for their philosophical discourses have all been lost except in a fragmentary form preserved in the works of various doxographers, and the best source is Aristotle. Although Aristotle’s interpretation of their thought dominated for centuries, modern scholars have gone beyond Aristotle to identify the original and unique contributions of the pre-Socratics.

In Athens, cultural activities such as tragedy flourished around fourth and fifth century B.C.E. Early philosophical activities, however, emerged in Eastern colonies of Asia Minor and Western Italian colonies. In Ionian colonies, the pursuit of material principle was primary and naturalism, holyzoism, and materialism developed. In Italian colonies, however, the pursuit of religious principles, logic, and mathematics developed.

Ionian School

The Ionian School, a type of Greek philosophy centred in Miletus, Ionia in the 6th and 5th centuries B.C.E., is something of a misnomer. Although Ionia was a centre of Western philosophy, the scholars it produced, including Anaximander, Anaximenes, Heraclitus, Anaxagoras, Diogenes Apolloniates, Archelaus, Hippon and Thales, had such diverse viewpoints that it cannot be said to be a specific school of philosophy. Aristotle called them physiologoi meaning 'those who discoursed on nature', but he did not group them together as an "Ionian school." The classification can be traced to the second century historian of philosophy Sotion. They are sometimes referred to as cosmologists, since they were largely physicalists who tried to explain the nature of matter.

While some of these scholars are included in the Milesian school of philosophy, others are more difficult to categorize.

Most cosmologists thought that although matter can change from one form to another, all matter has something in common which does not change. They did not agree what it was that all things had in common, and did not experiment to find out, but used abstract reasoning rather than mythology to explain themselves, thus becoming the first philosophers in the Western tradition.

Later philosophers widened their studies to include other areas of thought. The Eleatic school, for example, also studied epistemology, or how people come to know what exists. But the Ionians were the first group of philosophers that we know of, and so remain historically important.

Thales

Thales (Greek: Θαλης) of Miletus (ca. 624 B.C.E. - 545 B.C.E.) is generally understood as the earliest western philosopher. Before Thales, the Greeks explained the origin and nature of the world through myths of anthropomorphic gods and heroes. Phenomena like lightning or earthquakes were attributed to actions of the gods. By contrast, Thales attempted to find naturalistic explanations of the world, without reference to the supernatural. He explained earthquakes by imagining that the Earth floats on water, and that earthquakes occur when the Earth is rocked by waves.

Thales identified "water" as the ultimate principle or the original being, and held that all other beings were consisted of this ultimate element. Since no information source is available except short fragments, we do not know much about his reasoning. We can only speculate a number of reasons why he identified water as the universal, original element: water can take three forms (liquid, gas, slid) in natural temperatures; circulation of water is vital to changes in nature; the vital element of life; often used for religious rituals such as "purification."

Anaximander

Anaximander (Greek: Άναξίμανδρος) (611 B.C.E. – ca. 546 B.C.E.) has a reputation which is due mainly to a cosmological work, little of which remains. From the few extant fragments, we learn that he believed the beginning or first principle (arche, a word first found in Anaximander's writings, and which he probably invented) is an endless, unlimited, and unspecified mass (apeiron), subject to neither old age nor decay, which perpetually yields fresh materials from which everything we can perceive is derived. We can see a higher level of abstraction in Anaximander's concept of "unlimited mass" than earlier thinker like Thales who identified a particular element ("water") as the ultimate.

Anaximenes

Anaximenes (Greek: Άναξιμένης) of Miletus (585 B.C.E. - 525 B.C.E.) held that the air (breath), with its variety of contents, its universal presence, its vague associations in popular fancy with the phenomena of life and growth, is the source of all that exists. Everything is air at different degrees of density, and under the influence of heat, which expands, and of cold, which contracts its volume, it gives rise to the several phases of existence. The process is gradual, and takes place in two directions, as heat or cold predominates. In this way was formed a broad disk of earth, floating on the circumambient air. Similar condensations produced the sun and stars; and the flaming state of these bodies is due to the velocity of their motions.

Heraclitus

Heraclitus (Greek: Ἡράκλειτος) of Ephesus (ca. 535 - 475 B.C.E.) disagreed with Thales, Anaximander, and Pythagoras about the nature of the ultimate substance and claimed instead that everything is derived from the Greek classical element fire, rather than from air, water, or earth. This led to the belief that change is real, and stability illusory. For Heraclitus "Everything flows, nothing stands still." He is also famous for saying: "No man can cross the same river twice, because neither the man nor the river are the same." His concept of being as process or flux showed a sharp contrast with Parmenides who identified being as immutable.

Empedocles

Empedocles (ca. 490 B.C.E. – ca. 430 B.C.E.) was a citizen of Agrigentum, a Greek colony in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for being the origin of the cosmogenic theory of the four classical elements. He maintained that all matter is made up of four elements: water, earth, air and fire. Empedocles postulated something called Love (philia) to explain the attraction of different forms of matter, and of something called Strife (neikos) to account for their separation. He was also one of the first people to state the theory that light travels at a finite (although very large) speed, a theory that gained acceptance only much later.

Diogenes Apolloniates

Diogenes Apolloniates (ca. 460 B.C.E.) was a native of Apollonia in Crete. Like Anaximenes, he believed air to be the one source of all being, and all other substances to be derived from it by condensation and rarefaction. His chief advance upon the doctrines of Anaximenes is that he asserted air, the primal force, to be possessed of intelligence—"the air which stirred within him not only prompted, but instructed. The air as the origin of all things is necessarily an eternal, imperishable substance, but as soul it is also necessarily endowed with consciousness."

Archelaus

Archelaus was a Greek philosopher of the 5th century B.C.E., born probably in Athens, though Diogenes Laërtius (ii. 16) says in Miletus. He was a pupil of Anaxagoras, and is said by Ion of Chios (Diogenes Laërtius, ii. 23) to have been the teacher of Socrates. Some argue that this is probably only an attempt to connect Socrates with the Ionian School; others (e.g. Gomperz, Greek Thinkers) uphold the story. There is similar difference of opinion as regards the statement that Archelaus formulated certain ethical doctrines. In general, he followed Anaxagoras, but in his cosmology he went back to the earlier Ionians.

Pythagoras and Pythagoreans

Pythagoras (c. 570 B.C.E.-496 B.C.E.), Greek: Πυθαγόρας) was a mystic, and a mathematician, known best for the Pythagorean theorem.

The earliest Greek philosophers in Ionia, known as the Ionians, such as Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes, explored the origin of existing beings and developed theories of nature in order to explain the natural processes of the formation of the world. Pythagoras, who was born on an island off the coast of Ionia and later moved to Southern Italy, explored the question of the salvation of human beings by clarifying the essence of existing beings, and developing a mystical religious philosophy. Pythagoras developed both a theoretical foundation and a practical methodology, and formed an ascetic religious community. Followers of Pythagoras are known as Pythagoreans.

Pythagoras approached the question of being from an angle that was different from that of early Ionian philosophers. While the Ionians tried to find the original matter out of which the world is made, Pythagoras dove into the principles that give order and harmony to the elements of the world. In other words, Pythagoras found the essence of being not in “what is to be determined” but in “what determines.” From Pythagoras’ perspective, the Ionians’ prime elements, such as Thales’ “water” and Anaximander’s “indefinite,” were beings that were equally determined, and they did not explain why and how the world was orderly structured and maintained its rhythm and harmony.

According to Pythagoras, “number” or mathematical principle was that which gives order, harmony, rhythm, and beauty to the world. This harmony keeps a balance both in the cosmos and in the soul. For Pythagoras, “numbers” are not abstract concepts but embodied entities manifested as norms, cosmos, and sensible natural objects.

The mathematical order in beings is perceivable not by the physical senses but by senses of the soul. Unlike the modern concept of mathematical exercises, Pythagoras conceived mathematics as the method for liberating the soul from the bondages of bodily senses and essentially as religious training. For Pythagoras, the soul is immortal and the cultivation of the soul is achieved by the studies of truth and the ascetic life. Aristotle noted that Pythagoras was the first person who took up the issue of “virtue” in philosophy (DK. 58B4).

Pythagoras opened a new path to early Greek ontology by his focus on the soul, virtue, and the ascetic life. He presented a new integral model of thought where the mystic and the mathematical or the religious and the scientific (as well as the aesthetic) are uniquely integrated. This type of thought is uncommon in mainstream philosophy today. Like other wise men of antiquity, Pythagoras had a broad knowledge encompassing medicine, music, cosmology, astronomy, mathematics and others. Finally, his thought made a strong impact on Plato which is seen through his works.

Parmenides and the other Eleatic philosophers

The Eleatics were a school of pre-Socratic philosophers at Elea, a Greek colony in Campania, Italy. The group was founded in the early fifth century B.C.E. by Parmenides. Other members of the school included Zeno of Elea and Melissus of Samos. Xenophanes is sometimes included in the list, though there is some dispute over this.

The school took its name from Elea, a Greek city of lower Italy, the home of its chief exponents, Parmenides and Zeno. Its foundation is often attributed to Xenophanes of Colophon, but, although there is much in his speculations which formed part of the later Eleatic doctrine, it is probably more correct to regard Parmenides as the founder of the school.

Xenophanes had made the first attack on the mythology of early Greece in the middle of the 6th century, including an attack against the whole anthropomorphic system enshrined in the poems of Homer and Hesiod. In the hands of Parmenides this spirit of free thought developed on metaphysical lines. Subsequently, either because its speculations were offensive to the contemporary thought of Elea, or because of lapses in leadership, the school degenerated into verbal disputes as to the possibility of motion and other such academic matters. The best work of the school was absorbed into Platonic metaphysics.

The Eleatics rejected the epistemological validity of sense experience, and instead took mathematical standards of clarity and necessity to be the criteria of truth. Of the members, Parmenides and Melissus built arguments starting from indubitably sound premises. Zeno, on the other hand, primarily employed the reductio ad absurdum, attempting to destroy the arguments of others by showing their premises led to contradictions (Zeno's paradoxes).

The main doctrines of the Eleatics were evolved in opposition to the theories of the early physicalist philosophers, who explained all existence in terms of primary matter, and to the theory of Heraclitus, which declared that all existence may be summed up as perpetual change. The Eleatics maintained that the true explanation of things lies in the conception of a universal unity of being. According to their doctrine, the senses cannot cognize this unity, because their reports are inconsistent; it is by thought alone that we can pass beyond the false appearances of sense and arrive at the knowledge of being, at the fundamental truth that the All is One. Furthermore, there can be no creation, for being cannot come from non-being, because a thing cannot arise from that which is different from it. They argued that errors on this point commonly arise from the ambiguous use of the verb to be, which may imply existence or be merely the copula which connects subject and predicate.

Though the conclusions of the Eleatics were rejected by the later Presocratics and Aristotle, their arguments were taken seriously, and they are generally credited with improving the standards of discourse and argument in their time. Their influence was likewise longlasting — Gorgias, a Sophist, argued in the style of the Eleatics in his work "On Nature or What Is Not," and Plato acknowledged them in the Parmenides, the Sophist and the Politicus. Furthermore, much of the later philosophy of the ancient period borrowed from the methods and principles of the Eleatics.

Leucippus, Democritus and the other Atomists

Leucippus or Leukippos (Greek: Λεύκιππος, first half of 5th century B.C.E.) was among the earliest philosophers of atomism, the idea that everything is composed entirely of various imperishable, indivisible elements called atoms.

Democritus (Greek: Δημόκριτος) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher (born at Abdera in Thrace ca. 460 B.C.E. - died ca 370 B.C.E.).[1][2] Democritus was a student of Leucippus and co-originator of the belief that all matter is made up of various imperishable, indivisible elements which he called atoma (sg. atomon) or "indivisible units", from which we get the English word atom. It is virtually impossible to tell which of these ideas were unique to Democritus and which are attributable to Leucippus.

Sophists

The Greek words sophos or sophia had the meaning of "wise" or "wisdom" since the time of the poet Homer, and originally connoted anyone with expertise in a specific domain of knowledge or craft. Thus a charioteer, a sculptor, a warrior could be sophoi in their occupation. Gradually the word came to denote general wisdom (such as possessed by the Seven Sages of Greece), this is the meaning that appears in the histories of Herodotus. At about the same time, the term sophistes was a synonym for "poet", and (by association with the traditional role of poets as the teachers of society) a synonym for one who teaches, especially by writing prose works or speeches that impart practical knowledge.

In the second half of the 5th century B.C.E., and especially at Athens, "sophist" came to denote a class of itinerant intellectuals who employed rhetoric to achieve their purposes, generally to persuade or convince others. Most of these sophists are known today primarily through the writings of their opponents (specifically Plato and Aristotle), which makes it difficult to assemble an unbiased view of their practices and beliefs.

Many of them taught their skills, apparently often for a fee. Due to the importance of such skills in the litigious social life of Athens, practitioners of such skills often commanded very high fees. The practice of taking fees, coupled with the willingness of many sophists to use their rhetorical skills to pursue unjust lawsuits, eventually led to a decline in respect for practitioners of this form of teaching and the ideas and writings associated with it.

Protagoras is generally regarded as the first of these sophists. Others included Gorgias, Prodicus, Hippias, Thrasymachus, Lycophron, Callicles, Antiphon, and Cratylus.

In Plato's dialogs, Socrates challenged their moral relativism by arguing the eternal existence of truth.

Empedocles

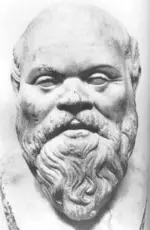

Socrates

Socrates, an Athenian philosopher, believed that a person should always try to do well. He believed that one should "know thyself." This is evidenced by the inscription at the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. He claimed that one has an obligation to disobey a bad command. He made his most important contribution to Western thought through his method of inquiry. In addition, he also taught many famous Greek philosophers. His most famous pupil was Plato. However, since Socrates discussed ideas that upset many people (some in high positions), he was sentenced to death by drinking the poison hemlock. The ironic thing about this is that during the reign of the Thirty Tyrants he was often threatened, but survived despite his continued protests for democracy. When democracy came, he was executed for corrupting their young. Most of what we know about Socrates came from Plato as Socrates wrote nothing down.

Plato and Aristotle

Aristotle, known as Aristoteles in most languages other than English (Aristotele in Italian), (384 B.C.E. - March 7, 322 B.C.E.) has, along with Plato, the reputation of one of the two most influential philosophers in Western thought.

Their works, although connected in many fundamental ways, differ considerably in both style and substance. Plato wrote several dozen philosophical dialogues—arguments in the form of conversations, usually with Socrates as a participant—and a few letters. Though the early dialogues deal mainly with methods of acquiring knowledge, and most of the last ones with justice and practical ethics, his most famous works expressed a synoptic view of ethics, metaphysics, reason, knowledge, and human life. Predominant ideas include the notion that knowledge gained through the senses always remains confused and impure, and that the contemplative soul that turns away from the world can acquire "true" knowledge. The soul alone can have knowledge of the Forms, the real essences of things, of which the world we see is but an imperfect copy. Such knowledge has ethical as well as scientific import. One can view Plato, with qualification, as an idealist and a rationalist.

Aristotle was one of Plato's students, but placed much more value on knowledge gained from the senses, and would correspondingly better earn the modern label of empiricist. Thus Aristotle set the stage for what would eventually develop into the scientific method centuries later. The works of Aristotle that still exist today appear in treatise form, mostly unpublished by their author. The most important include Physics, Metaphysics, (Nicomachean) Ethics, Politics, De Anima (On the Soul), Poetics, and many others.

Aristotle was a great thinker and philosopher, and was called 'the master' by Avicenna in the following centuries. His views and approaches dominated early Western science for almost 2000 years. As well as philosophy, Aristotle was a formidable inventor, and is credited with many significant inventions and observations. Robert M. Pirsig, the author of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, makes the observation that Aristotle both helped create the analytic approach which forms the backbone of the scientific method and much of philosophy, but that against this, he also took great pride in categorizing nature into lists and taxonomic schemes, which in some cases led to subjects such as rhetoric evolving over time from rich art forms, into recipe-like rules.

Schools of thought in the Hellenistic period

In the Hellenistic period, many different schools of thought developed in the Greek world and often attracted Romans who were responsible for the development of these Greek philosophies. The most notable schools were:

- Neo-Platonism: Ammonius Saccas, Porphyry, Plotinus (Roman), Iamblichus, Proclus

- Academic Skepticism: Arcesilaus, Carneades

- Pyrrhonian Skepticism: Pyrrho, Sextus Empiricus

- Cynicism: Antisthenes, Diogenes of Sinope, Crates of Thebes (taught Zeno of Citium, founder of Stoicism)

- Stoicism: Zeno of Citium, Crates of Mallus (brought Stoicism to Rome c. 170 B.C.E.), Seneca (Roman), Epictetus (Roman), Marcus Aurelius (Roman)

- Epicureanism: Epicurus and Lucretius (Roman)

- Eclecticism: Cicero (Roman)

The spread of Christianity through the Roman world ushered in the end of the Hellenistic philosophy and the beginnings of Medieval Philosophy.

Notes

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica. Democritus. Retrieved 2006-10-21.

- ↑ Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Democritus. Retrieved 2006-08-01.

See also

- Ancient philosophy

- Aristotelianism

- Paideia

- Philosophy

- Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance—a book which inter alia examines the nature of Greek philosophy and its early development.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- John Burnet, Early Greek Philosophy, 1930.

- William Keith Chambers Guthrie, A History of Greek Philosophy: Volume 1, The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans, 1962.

- Martin Litchfield West, Early Greek Philosophy and the Orient, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1971.

- Martin Litchfield West, The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth, Oxford [England] ; New York: Clarendon Press, 1997.

- Charles Freeman (1996). Egypt, Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press.

External links

- The Impact of Greek Culture on Normative Judaism from the Hellenistic Period through the Middle Ages c. 330 B.C.E.- 1250 C.E.

- Greek Philosophy for Kids

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Greek_philosophy history

- Ionian_School history

- Eleatics history

- Leucippus history

- Democritus history

- Sophism history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.