Poe, Edgar Allan

m (Robot: Remove claimed tag) |

|||

| (78 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} |

{{epname|Poe, Edgar Allan}} | {{epname|Poe, Edgar Allan}} | ||

| − | |||

{{Infobox Writer | {{Infobox Writer | ||

| − | + | | name = Edgar Allan Poe | |

| − | | name | + | | image = Edgar_Allan_Poe_2.jpg |

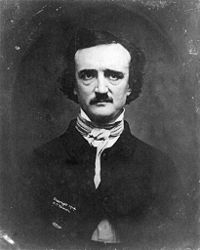

| − | | image | + | | caption = 1848 [[daguerreotype]] of Poe |

| − | | caption | + | | pseudonym = |

| − | | | + | | birthname = |

| − | | | + | | birthdate = {{birth date|mf=yes|1809|01|19}} |

| − | | | + | | birthplace = [[Boston]], [[Massachusetts]], [[United States|USA]] |

| − | | | + | | deathdate = {{death date and age|mf=yes|1849|10|7|1809|01|19}} |

| − | | occupation | + | | deathplace = [[Baltimore]], [[Maryland]], USA |

| − | + | | occupation = [[Poetry|Poet]], [[Short story|short-story writer]], [[Editing|editor]], [[Literary criticism|literary critic]] | |

| − | | genre | + | | nationality = |

| − | | | + | | ethnicity = |

| − | | | + | | citizenship = |

| − | | | + | | education = |

| − | | spouse | + | | alma_mater = |

| − | | | + | | period = |

| − | | | + | | genre = [[Horror fiction]], [[crime fiction]], [[detective fiction]] |

| + | | subject = | ||

| + | | movement = [[Romanticism]] | ||

| + | | notableworks = | ||

| + | | spouse = [[Virginia Eliza Clemm Poe]] | ||

| + | | partner = | ||

| + | | children = | ||

| + | | relatives = | ||

| + | | influences = | ||

| + | | influenced = | ||

| + | | awards = | ||

| + | | signature = | ||

| + | | website = | ||

| + | | portaldisp = | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Edgar Allan Poe''' (January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American [[poet]], [[Short story|short-story]] writer, [[Editing|editor]] and [[Literary criticism|literary critic]], and is considered part of the American [[Romanticism|Romantic Movement]]. Best known for his tales of [[Mystery (fiction)|mystery]] and the [[macabre]], Poe was one of the earliest American practitioners of the short story. He is considered the inventor of the [[detective fiction]] genre as well as contributing to the emerging genre of [[science fiction]]. He was the first well-known American writer to try to earn a living through writing alone, resulting in a financially difficult life and career. Although his poem ''[[The Raven]]'', published in January 1845, was highly acclaimed, it brought him little financial reward. | |

| − | + | The darkness that characterized many of Poe's writings appears to have roots in his life. Born Edgar Poe in [[Boston]], [[Massachusetts]], he was soon left without parents; John and Frances Allan took him in as a [[foster child]] but they never formally [[adoption|adopted]] him. In 1835, he married [[Virginia Eliza Clemm Poe|Virginia Clemm]], his 13-year-old cousin; unfortunately, in 1942 she contracted [[tuberculosis]] and died five years later. Her sickness and death took a great toll on Poe. Two years later, at age 40, Poe died in [[Baltimore]] under strange circumstances. The cause of his death has remained unknown and has been variously attributed to [[alcohol]], brain congestion, [[cholera]], drugs, [[heart disease]], [[rabies]], [[suicide]], tuberculosis, and other agents. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Poe's works remain popular and influential, both in terms of their style and content. His fascination with [[death]] and violence, the loss of a beloved, possibilities of reanimation or life beyond the grave in some physical form, and with macabre and tragic mysteries continue to intrigue readers worldwide, reflecting human interest in [[life after death]] and desire for the revealing of truth. His interest and works in areas such as [[cosmology]] and [[cryptography]] showed an intuitive intelligence with ideas ahead of his time. Poe continues to appear throughout popular culture in literature, music, films, and television. | ||

| − | + | ==Life== | |

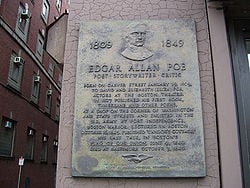

| − | + | [[Image:Edgar Allan Poe Birthplace Boston.jpg|thumb|250 px|This plaque marks the approximate location where Edgar Poe was born in Boston.]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ==Life | ||

| − | [[Image:Edgar Allan Poe | ||

===Early life=== | ===Early life=== | ||

| − | + | '''Edgar Poe''' was born in [[Boston, Massachusetts]], on January 19, 1809, the second child of actress [[Eliza Poe|Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins Poe]] and actor David Poe, Jr. He had an elder brother, [[William Henry Leonard Poe]], and a younger sister, Rosalie Poe.<ref name="hervey">Hervey Allen, "Introduction," ''The Works of Edgar Allan Poe'' (New York, NY: P. F. Collier & Son, 1927).</ref> His father abandoned their family in 1810, and his mother died a year later from [[tuberculosis|consumption]]. Poe was then taken into the home of John Allan, a successful Scottish merchant in [[Richmond, Virginia]], who dealt in a variety of goods including tobacco, cloth, wheat, tombstones, and [[slavery|slaves]].<ref>Jeffrey Meyers, ''Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy'' (New York, NY: Cooper Square Press, 1992, ISBN 0815410387), 8.</ref> The Allans served as a [[foster family]] but never formally [[adoption|adopted]] him,<ref>Arthur Hobson Quinn, ''Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography'' (New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1941, ISBN 0801857309), 61.</ref> although they gave him the name "Edgar Allan Poe."<ref name=Meyers9>Meyers, 9.</ref> | |

| − | The Allan family had | + | The Allan family had Poe baptized in the [[Episcopal Church in the United States of America|Episcopal Church]] in 1812. John Allan alternately spoiled and aggressively disciplined his foster son.<ref name=Meyers9/> The family, including Poe and Allan's wife, Frances Valentine Allan, sailed to England in 1815. Poe attended the [[grammar school]] in [[Irvine, North Ayrshire|Irvine]], [[Scotland]] (where John Allan was born) for a short period in 1815, before rejoining the family in London in 1816. He studied at a [[boarding school]] in [[Chelsea, London|Chelsea]] until summer 1817. He was subsequently entered at the Reverend John Bransby’s Manor House School at [[Stoke Newington]], then a suburb four miles (6 km) north of London.<ref>Kenneth Silverman, ''Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-Ending Remembrance'' (New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1991, ISBN 0060923318), 16–18.</ref> |

| − | Poe moved back with the Allans to Richmond, Virginia in 1820. In 1825, John Allan's | + | Poe moved back with the Allans to Richmond, Virginia in 1820. In March 1825, John Allan's uncle<ref>Meyers, 20.</ref> and business benefactor William Galt, said to be one of the wealthiest men in Richmond, died and left Allan several acres of real estate. The inheritance was estimated at $750,000. By summer 1825, Allan celebrated his expansive wealth by purchasing a two-story brick home named Moldavia.<ref>Silverman, 27–28.</ref> Poe may have become engaged to [[Sarah Elmira Royster]] before he registered at the one-year-old [[University of Virginia]] in February 1826 to study languages.<ref>Silverman, 29–30.</ref> Although he excelled in his studies, during his time there Poe lost touch with Royster and also became estranged from his foster father over [[gambling]] debts and his foster father's refusal to cover all his expenses. Poe withdrew permanently from the school after only one year of study, and, not feeling welcome in Richmond, especially when he learned that his sweetheart Royster had married Alexander Shelton, he traveled to [[Boston]] in April 1827, sustaining himself with odd jobs as a clerk and newspaper writer.<ref name=Meyers32>Meyers, 32.</ref> At some point he started using the [[pseudonym]] Henri Le Rennet.<ref>Silverman, 41.</ref> That same year, he released his first book, a 40-page collection of [[poetry]], ''[[Tamerlane and Other Poems]]'', attributed with the byline "by a Bostonian." Only 50 copies were printed, and the book received virtually no attention.<ref>Meyers, 33–34.</ref> |

===Military career=== | ===Military career=== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:FtIndependence2.jpg|left|thumb|250 px|Poe was first stationed at Boston's [[Fort Independence (Massachusetts)|Fort Independence]] while in the army.]] | |

| + | Unable to support himself, on May 27, 1827, Poe enlisted in the [[United States Army]] as a private. Using the name "Edgar A. Perry," he claimed he was 22 years old even though he was 18.<ref name=Cornelius>Kay Cornelius, "Biography of Edgar Allan Poe," Harold Bloom (ed.) ''Bloom's BioCritiques: Edgar Allan Poe'' (Philadelphia, PA: Chelsea House Publishers, 2002, ISBN 0791061736), 13-14.</ref> He first served at [[Fort Independence (Massachusetts)|Fort Independence]] in [[Boston Harbor]].<ref name=Meyers32/> Poe's regiment was then posted to [[Fort Moultrie National Monument|Fort Moultrie]] in [[Charleston, South Carolina]] and traveled there by ship on the brig ''Waltham'' on November 8, 1827. Poe was promoted to "artificer," an enlisted tradesman who prepared shells for [[artillery]], and had his monthly pay doubled.<ref>Meyers, 35.</ref> After serving for two years and attaining the rank of Sergeant Major for Artillery (the highest rank a non-commissioned officer can achieve), Poe sought to end his five-year enlistment early. He revealed his real name and his circumstances to his [[commanding officer]], Lieutenant Howard. Howard would allow Poe to be [[military discharge|discharged]] only if he reconciled with John Allan. His foster mother, Frances Allan, died on February 28, 1829, and Poe visited the day after her burial. Perhaps softened by his wife's death, John Allan agreed to support Poe's attempt to be discharged in order to receive an appointment to the [[United States Military Academy]] at [[West Point]].<ref>Silverman, 43–47.</ref> | ||

| − | Poe | + | Poe was discharged on April 15, 1829, after securing a replacement to finish his enlisted term for him.<ref>Meyers, 38.</ref> Before entering West Point, Poe moved back to [[Baltimore]] for a time, to stay with his widowed aunt Maria Clemm, her daughter, [[Virginia Eliza Clemm Poe|Virginia Eliza Clemm]] (Poe's first cousin), his brother Henry, and his invalid grandmother Elizabeth Cairnes Poe.<ref name=Cornelius/> Meanwhile, Poe published his second book, ''Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane and Minor Poems'', in Baltimore in 1829.<ref>Dawn B. Sova, ''Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z'' (New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2001, ISBN 081604161X), 5.</ref> |

| − | Poe traveled to West Point | + | Poe traveled to West Point and matriculated as a cadet on July 1, 1830.<ref>Joseph Wood Krutch, ''Edgar Allan Poe: A Study in Genius'' (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1926), 32.</ref> In October 1830, John Allan married his second wife, Louisa Patterson.<ref name=Cornelius/> The marriage, and bitter quarrels with Poe over the children born to Allan out of affairs, led to the foster father finally disowning Poe.<ref>Meyers, 54–55.</ref> Poe decided to leave West Point by purposely getting [[court-martial]]ed. On February 8, 1831, he was tried for gross neglect of duty and disobedience of orders for refusing to attend formations, classes, or church. Poe tactically pled not guilty to induce dismissal, knowing he would be found guilty.<ref>William J. Hecker, ''Private Perry and Mister Poe: The West Point Poems'' (Louisiana State University Press, 2005), 49–51.</ref> |

| − | + | He left for New York in February 1831, and released a third volume of poems, simply titled ''Poems.'' The book was financed with help from his fellow cadets at West Point; they may have been expecting verses similar to the [[satire|satirical]] ones Poe had been writing about commanding officers.<ref>Meyers, 50–51.</ref> Printed by Elam Bliss of New York, it was labeled as "Second Edition" and included a page saying, "To the U.S. Corps of Cadets this volume is respectfully dedicated." The book once again reprinted the long poems "Tamerlane" and "Al Aaraaf" but also six previously unpublished poems including early versions of "[[To Helen]]," "[[Israfel]]," and "[[The City in the Sea]]".<ref>Hecker, 53–54.</ref> He returned to Baltimore, to his aunt, brother and cousin, in March 1831. His elder brother Henry, who had been in ill health in part due to problems with [[alcoholism]], died on August 1, 1831.<ref>Quinn, 187–188.</ref> | |

| − | He | ||

| − | + | ===Marriage=== | |

| + | [[File:P1020279.JPG|thumb|left|250 px|Poe spent the last few years of his life in a small cottage in the [[Fordham, Bronx|Bronx, New York]].]] | ||

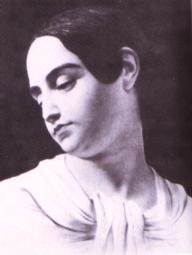

| + | Poe secretly married Virginia, his cousin, on September 22, 1835. She was 13 at the time, though she is listed on the marriage certificate as being 21.<ref>Meyers, 85.</ref> On May 16, 1836, they had a second wedding ceremony in Richmond, this time in public.<ref>Silverman, 124.</ref> | ||

| − | + | One evening in January 1842, Virginia showed the first signs of consumption, now known as [[tuberculosis]], while singing and playing the piano. Poe described it as breaking a blood vessel in her throat.<ref>Silverman, 179.</ref> She only partially recovered, and Poe began to drink more heavily under the stress of his wife's illness. In 1946, Poe moved to [[Edgar Allan Poe Cottage|a cottage]] in the [[Fordham, Bronx|Fordham]] section of [[The Bronx, New York]]. Virginia died there on January 30, 1847.<ref name="Poe Cottage">[http://bronxhistoricalsociety.org/poe-cottage/ The Edgar Allan Poe Cottage] Bronx Historical Society. Retrieved February 26, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Increasingly unstable after his wife's death, Poe attempted to court the poet [[Sarah Helen Whitman]], who lived in [[Providence, Rhode Island]]. Their engagement failed, purportedly because of Poe's drinking and erratic behavior. However, there is also evidence that Whitman's mother intervened and did much to derail their relationship.<ref>Richard P. Benton, [http://www.eapoe.org/papers/psbbooks/pb19871c.htm “Friends and Enemies: Women in the Life of Edgar Allan Poe,”] Retrieved February 26, 2020. In Benjamin Franklin Fisher (ed.), ''Myths and Reality: The Mysterious Mr. Poe'' (Baltimore, MD: Edgar Allan Poe Society, 1987, ISBN 0961644915). </ref> Poe then returned to Richmond and resumed a relationship with his childhood sweetheart, Sarah Elmira Royster, whose husband had died in 1944.<ref>Quinn, 628.</ref> | |

| + | [[Image:Poe's grave Baltimore MD.jpg|thumb|upright|180px|Edgar Allan Poe is buried in [[Baltimore, Maryland]]. The circumstances and cause of his death remain uncertain.]] | ||

| − | + | ===Death=== | |

| + | On October 3, 1849, Poe was found on the streets of [[Baltimore]] delirious, "in great distress, and... in need of immediate assistance," according to the man who found him, Joseph W. Walker.<ref>Quinn, 638.</ref> He was taken to the Washington College Hospital, where he died on Sunday, October 7, 1849.<ref name=Meyers255>Meyers, 255.</ref> Poe was never coherent long enough to explain how he came to be in his dire condition, and, oddly, was wearing clothes that were not his own. All medical records, including his death certificate, have been lost.<ref>Birgit Bramsback, "The Final Illness and Death of Edgar Allan Poe: An Attempt at Reassessment," ''Studia Neophilologica'' (University of Uppsala, 1970), XLII, 40.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Newspapers at the time reported Poe's death as "congestion of the brain" or "cerebral inflammation," common [[euphemism]]s for deaths from disreputable causes such as [[alcoholism]]; the actual cause of his death, however, remains a mystery.<ref>Silverman, 435–436.</ref> From as early as 1872, [[cooping]] (a practice in the United States by which unwilling participants were forced to vote multiple times for a particular candidate in an election; they were given alcohol or drugs in order for them to comply) was commonly believed to have been the cause,<ref name=Walsh>John Evangelist Walsh, ''Midnight Dreary: The Mysterious Death of Edgar Allan Poe'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, ISBN 978-0312227326).</ref> and speculation has included ''[[delirium tremens]]'', [[heart disease]], [[epilepsy]], [[syphilis]], [[meningitis|meningeal inflammation]],<ref name=Meyers256>Meyers, 256.</ref> [[cholera]], brain tumor, and even [[rabies]] as medical causes; [[murder]] has also been suggested.<ref>Natasha Geiling, [https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/still-mysterious-death-edgar-allan-poe-180952936/ The (Still) Mysterious Death of Edgar Allan Poe] ''Smithsonian Magazine'', October 7, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2020.</ref> <ref name=Walsh/> | |

| − | + | ==Career== | |

| + | Poe was the first well-known American author and poet to try to live on his writing alone.<ref name=Meyers138>Meyers, 138.</ref><ref name=Quinn305>Quinn, 305.</ref> He chose a difficult time in American publishing to do so.<ref name=Whalen>Terance Whalen, "Poe and the American Publishing Industry." In J. Gerald Kennedy (ed.), ''A Historical Guide to Edgar Allan Poe'' (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0195121506), 63–94.</ref> He was hampered by the lack of an international [[copyright]] law.<ref>Silverman, 247.</ref> Publishers often pirated copies of British works rather than paying for new work by Americans.<ref name=Quinn305/> The industry was also particularly hurt by the [[Panic of 1837]].<ref name=Whalen/> Despite a booming growth in American periodicals around this time period, fueled in part by new technology, many did not last beyond a few issues<ref>Silverman, 99.</ref> and publishers often refused to pay their writers or paid them much later than they promised.<ref name=Whalen/> As a result Poe, throughout his attempts at pursuing a successful literary career, was forced to constantly make humiliating pleas for money and other assistance.<ref>Meyers, 139.</ref> | ||

| − | + | [[Image:VirginiaPoe.jpg|right|thumb|Poe married his 13-year old cousin, [[Virginia Eliza Clemm Poe|Virginia Clemm]]. Her early death may have inspired some of his writing.]] | |

| − | [[Image: | + | After his early attempts at poetry, Poe turned his attention to prose. He placed a few stories with a [[Philadelphia]] publication and began work on his only drama, ''[[Politian (play)|Politian]]''. The ''Saturday Visitor'', a Baltimore paper, awarded Poe a prize in October 1833 for his short story "[[MS. Found in a Bottle]]".<ref>Sova, 162.</ref> The story brought him to the attention of [[John P. Kennedy]], a Baltimorian of considerable means. He helped Poe place some of his stories, and introduced him to Thomas W. White, editor of the ''[[Southern Literary Messenger]]'' in [[Richmond, Virginia|Richmond]]. Poe became assistant editor of the periodical in August 1835;<ref>Sova, 225.</ref> however, within a few weeks, he was discharged after repeatedly being found drunk.<ref>Meyers, 73.</ref> Reinstated by White after promising good behavior, Poe went back to Richmond with Virginia and her mother. He remained at the ''Messenger'' until January 1837, publishing several poems, book reviews, criticism, and stories in the paper. During this period, its circulation increased from 700 to 3,500.<ref name="hervey" /> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Poe | + | ''[[The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket|The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym]]'' was published and widely reviewed in 1838. In the summer of 1839, Poe became assistant editor of ''[[Burton's Gentleman's Magazine]]''. He published numerous articles, stories, and reviews, enhancing his reputation as a trenchant critic that he had established at the ''Southern Literary Messenger''. Also in 1839, the collection ''[[Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque]]'' was published in two volumes, though it made him little money received mixed reviews.<ref>Meyers, 113.</ref> Poe left ''Burton's'' after about a year and found a position as assistant at ''[[Graham's Magazine]]''.<ref>Sova, 39, 99.</ref> |

| − | + | In June 1840, Poe published a prospectus announcing his intentions to start his own journal, ''[[The Stylus]]''.<ref>Meyers, 119.</ref> Originally, Poe intended to call the journal ''The Penn'', as it would have been based in [[Philadelphia]], Pennsylvania. In the June 6, 1840 issue of Philadelphia's ''[[Saturday Evening Post]]'', Poe bought [[advertising]] space for his prospectus: ''"Prospectus of the Penn Magazine, a Monthly Literary journal to be edited and published in the city of Philadelphia by Edgar A. Poe."''<ref>Silverman, 159.</ref> The journal would never be produced before Poe's death. | |

| − | The | ||

| − | + | He left ''Graham's'' and attempted to find a new position, for a time angling for a government post. He returned to New York, where he worked briefly at the ''Evening Mirror'' before becoming editor of the ''[[Broadway Journal]]'' and, later, sole owner.<ref name=Sova34>Sova, 34.</ref> There he alienated himself from other writers by publicly accusing [[Henry Wadsworth Longfellow]] of [[plagiarism]], though Longfellow never responded.<ref>Quinn, 455.</ref> On January 29, 1845, his poem "[[The Raven]]" appeared in the ''Evening Mirror'' and became a popular sensation. Though it made Poe a household name almost instantly,<ref>Hoffman, 80.</ref> he was paid only $9 for its publication.<ref>John Ward Ostrom, "Edgar A. Poe: His Income as Literary Entrepreneur," ''Poe Studies'' 5.1 (1982): 5.</ref> The ''Broadway Journal'' failed in 1846.<ref name=Sova34/> | |

| − | === | + | ==Literary style and themes== |

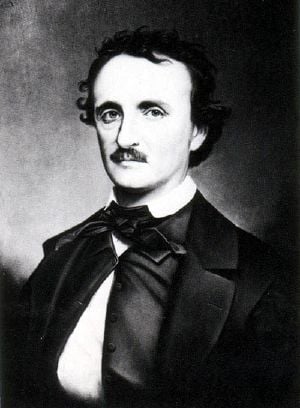

| − | + | [[Image:Edgar Allan Poe portrait B.jpg|thumb|1860s portrait by Oscar Halling after an 1849 [[daguerreotype]]]] | |

| − | + | ===Genres=== | |

| + | Poe's best known fiction works are [[Gothic fiction|Gothic]],<ref>Meyers, 64.</ref> a genre he followed to appease the public taste.<ref name=Royot> Daniel Royot, "Poe's Humor," Kevin J. Hayes (ed.), ''The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe'' (Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0521797276).</ref> Many of his works are generally considered part of the [[dark romanticism]] genre, a literary reaction to [[transcendentalism]], which Poe strongly disliked.<ref name=Kent> Kent Ljunquist, "The poet as critic," Kevin J. Hayes (ed.), ''The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe'' (Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0521797276), 15.</ref> He referred to followers of that movement as "Frogpondians" after the pond on [[Boston Common (park)|Boston Common]].<ref name=Royot/> and ridiculed their writings as "[[metaphor]]-run," lapsing into "obscurity for obscurity's sake" or "mysticism for mysticism's sake."<ref name=Kent/> | ||

| − | + | Poe described many of his works as "tales of ratiocination"<ref> Silverman, 171.</ref> in which the primary concern of the plot is ascertaining truth, and the means of obtaining the truth is a complex and mysterious process combining intuitive logic, astute observation, and perspicacious inference. Such stories, especially those featuring the fictional [[detective]], C. Auguste Dupin, laid the groundwork for future detectives in literature. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Poe | + | Much of Poe's poetry and prose features his characteristic interest in exploring the [[psychology]] of man, including the perverse and self-destructive nature of the conscious and [[subconscious]] mind which leads to [[insanity]]. His most recurring themes deal with questions of [[death]], including its physical signs, the effects of decomposition, concerns of [[premature burial]], the reanimation of the dead, and [[mourning]].<ref>J. Gerald Kennedy, ''Poe, Death, and the Life of Writing'' (Yale University Press, 1987, ISBN 0300037732), 3.</ref> Biographers and critics have often suggested that Poe's frequent theme of the "death of a beautiful woman" stems from the repeated loss of women throughout his life, including his wife.<ref>Karen Weekes, "Poe's feminine ideal," Kevin J. Hayes (ed.), ''The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe'' (Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0521797276), 149. </ref> Some of Poe’s notable dark romantic works include the short stories "[[Ligeia]]" and "[[The Fall of the House of Usher]]" and poems "[[The Raven]]" and "[[Ulalume]]." |

| − | + | Poe's works often feature an unnamed narrator and the tale or poem tracks his descent into madness. For example, the narrator of Poe's classic Gothic short story, ''[[The Tell-Tale Heart]]'', endeavors to convince the reader of his [[sanity]], while describing a [[murder]] he committed. The murder is carefully calculated, and the murderer dismembered the body and hid it under the floorboards. Ultimately the narrator's guilt manifests itself in an auditory [[hallucination]]: The narrator hears the man's [[heart]] still beating under the floorboards. Poe's poem ''[[The Raven]]'' is often noted for its musicality, stylized language, and [[supernatural]] atmosphere. It tells of a talking [[raven]]'s mysterious visit to an unnamed narrator, tracing his slow fall into madness. The narrator is distraught, lamenting the loss of his love, Lenore. The raven seems to further instigate his distress with its constant repetition of the word "Nevermore." | |

| − | + | Beyond horror, Poe also wrote [[satire]]s, humor tales, and [[hoax]]es. For comic effect, he used [[irony]] and ludicrous extravagance, often in an attempt to liberate the reader from cultural conformity.<ref name=Royot/> In fact, "[[Metzengerstein]]," the first story that Poe is known to have published,<ref>Silverman, 88.</ref> and his first foray into horror, was originally intended as a [[burlesque (genre)|burlesque]] satirizing the popular genre.<ref>Benjamin Franklin Fisher, "Poe's 'Metzengerstein': Not a Hoax," ''On Poe: The Best from "American Literature'' (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993), 142, 149.</ref> Poe also contributed to the emerging genre of [[science fiction]], responding in his writing to emerging technologies such as [[hot air balloon]]s in "[[The Balloon-Hoax]]".<ref>John Tresch, "Extra! Extra! Poe invents science fiction!" Kevin J. Hayes (ed.), ''The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe'' (Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0521797276), 114.</ref><ref>Brian Stableford, "Science fiction before the genre." Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn (eds.), ''The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 18–19.</ref> | |

| − | Poe | + | Poe wrote much of his work using themes specifically catered for mass market tastes.<ref name=Whalen/> To that end, his fiction often included elements of popular [[pseudoscience]]s such as [[phrenology]]<ref>Edward Hungerford, "Poe and Phrenology," ''American Literature'' 1 (1930): 209–231.</ref> and [[physiognomy]].<ref>Erik Grayson, "Weird Science, Weirder Unity: Phrenology and Physiognomy in Edgar Allan Poe," ''Mode'' 1 (2005): 56–77.</ref> |

| − | He | + | ===Literary theory=== |

| + | Poe's writing reflects his literary theories, which he presented in his criticism and also in essays such as "[[The Poetic Principle]]."<ref name=Krutch225>Krutch, 225.</ref> He disliked [[didacticism]]<ref name=Kagle104>Steven E. Kagle, "The Corpse Within Us," Benjamin Franklin Fisher IV (ed.), ''Poe and His Times: The Artist and His Milieu'' (Baltimore, MD: The Edgar Allan Poe Society, Inc., 1990, ISBN 0961644923), 104.</ref> and [[allegory]],<ref>Edgar Allan Poe, [https://www.eapoe.org/works/CRITICSM/GLB47HN1.HTM "Tale-Writing—Nathaniel Hawthorne"], ''Godey's Lady's Book'' (November 1847), 252–256. Retrieved March 5, 2020.</ref> though he believed that meaning in literature should be an undercurrent just beneath the surface. Works with obvious meanings, he wrote, cease to be art.<ref name=Wilbur99>Richard Wilbur, "The House of Poe," Robert Regan (ed.), ''Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays'' (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1967), 99.</ref> He believed that quality work should be brief and focus on a specific single effect.<ref name=Krutch225/> To that end, he believed that the writer should carefully calculate every sentiment and idea.<ref>Pasquale Jannaccone, (translated by Peter Mitilineos) "[https://www.eapoe.org/pstudies/ps1970/p1974101.htm The Aesthetics of Edgar Poe]," ''Poe Studies'' VII(1, 7) (June 1974):1-13. Retrieved March 5, 2020.</ref> In "[[The Philosophy of Composition]]," an essay in which Poe describes his method in writing "The Raven," he claims to have strictly followed this method. | ||

| − | Poe | + | ===Cryptography=== |

| − | + | Poe had a keen interest in the field of [[cryptography]]. He had placed a notice of his abilities in the [[Philadelphia]] paper ''Alexander's Weekly (Express) Messenger'', inviting submissions of [[cipher]]s, which he proceeded to solve.<ref name=Silverman152>Silverman, 152.</ref> In July 1841, Poe had published an essay called "A Few Words on Secret Writing" in ''[[Graham's Magazine]]''. Realizing the public interest in the topic, he wrote "[[The Gold-Bug]]" incorporating ciphers as part of the story.<ref>Rosenheim, 2, 6.</ref> Poe's success in cryptography relied not so much on his knowledge of that field (his method was limited to the simple substitution cryptogram), as on his knowledge of the magazine and newspaper culture. His keen analytical abilities, which were so evident in his detective stories, allowed him to see that the general public was largely ignorant of the methods by which a simple substitution cryptogram can be solved, and he used this to his advantage.<ref name=Silverman152/> The sensation Poe created with his cryptography stunt played a major role in popularizing cryptograms in newspapers and magazines.<ref>William F. Friedman, "Edgar Allan Poe, Cryptographer," Louis J. Budd and Edwin H. Cady (eds.), ''On Poe: The Best from American Literature'' (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0822313113), 40–41.</ref> | |

| − | Poe | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The effect of Poe's interest in cryptography extended beyond increasing public interest in his lifetime. [[William Friedman]], America's foremost cryptologist, was initially interest in cryptography after reading "The Gold-Bug" as a child —an interest he later put to use in deciphering Japan's [[PURPLE]] code during [[World War II]].<ref>Rosenheim, 146.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Physics and cosmology=== | ===Physics and cosmology=== | ||

| − | ''[[Eureka | + | ''[[Eureka: A Prose Poem]]'', an essay written in 1848, was subtitled "An Essay on the Material and Spiritual Universe" and included a [[cosmology|cosmological]] theory that presaged the [[big bang]] theory by 80 years.<ref>Terry Rombeck, "[https://www2.ljworld.com/news/2005/jan/22/poes_littleknown_science/ Poe's little-known science book reprinted]," ''Lawrence Journal-World & News'' (January 22, 2005). Retrieved March 5, 2020.</ref> Adapted from a lecture he had presented on February 3, 1848 entitled "On The Cosmography of the Universe" at the Society Library in New York, ''Eureka'' describes Poe's intuitive conception of the nature of the universe. Poe eschewed the scientific method in ''Eureka'' and instead wrote from pure [[intuition (knowledge)|intuition]]. For this reason, he considered it a work of art, not science,<ref> Meyers, 214.</ref> |

| − | + | ''Eureka'' was received poorly in Poe's day and generally described as absurd, even by friends. It is full of scientific errors. In particular, Poe's suggestions opposed [[Newton's laws of motion|Newtonian principles]] regarding the density and rotation of planets.<ref>Sova, 82.</ref> Nevertheless, he considered it to be his career masterpiece.<ref>Meyers, 219.</ref> | |

| − | === | + | ==Legacy== |

| − | Poe | + | ===Griswold's "Memoir"=== |

| + | The day Edgar Allan Poe was buried, a long obituary appeared in the ''[[New York Tribune]]'' signed "Ludwig." It was soon published throughout the country. The piece began, "Edgar Allan Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it."<ref>Meyers, 259. </ref> "Ludwig" was soon identified as [[Rufus Wilmot Griswold]], an editor, critic, and anthologist who had borne a grudge against Poe since 1842. | ||

| − | Poe's | + | Griswold somehow became Poe's [[literary executor]] and attempted to destroy his enemy's reputation after his death.<ref name=Hoffman14>Hoffman, 14.</ref> He wrote a biographical article of Poe called "Memoir of the Author," which he included in an 1850 volume of the collected works. Griswold depicted Poe as a depraved, drunk, drug-addled madman and included Poe's letters as evidence.<ref name=Hoffman14/> These letters were later revealed as [[forgery|forgeries]].<ref>Quinn, 699.</ref> In fact, many of his claims were either outright lies or distorted half-truths. For example, it is now known that Poe was not a drug addict.<ref>Quinn, 693.</ref> Griswold's book was denounced by those who knew Poe well,<ref>Sova, 101.</ref> but it became a popularly accepted one, in part because it was the only full biography available and in part because readers thrilled at the thought of reading works by an "evil" man.<ref>Meyers, 263.</ref> |

| − | Poe | + | ===Poe Toaster=== |

| + | Adding to the mystery surrounding Poe's death, an unknown visitor affectionately referred to as the "Poe Toaster" has paid homage to Poe's grave every year since 1949. As the tradition has been carried on for more than 50 years, it is likely that the "Poe Toaster" is actually several individuals; however, the tribute is always the same. Every January 19, in the early hours of the morning, a figure dressed in black lays three roses and a bottle of cognac at the Poe's original grave marker. Members of the Edgar Allan Poe Society in Baltimore have helped in protecting this tradition for decades. | ||

| − | + | On August 15, 2007, Sam Porpora, a former historian at the Westminster Church in Baltimore where Poe is buried, claimed that he had started the tradition in the 1960s. The claim that the tradition began in 1949, he said, was a hoax in order to raise money and enhance the profile of the church. His story has not been confirmed, and some details he has given to the press have been pointed out as factually inaccurate.<ref>Associated Press, [https://www.foxnews.com/story/man-reveals-legend-of-mystery-visitor-to-edgar-allan-poes-grave Man Reveals Legend of Mystery Visitor to Edgar Allan Poe's Grave] ''FoxNews.com'', January 13, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ===Literary influence=== |

| − | ===Poe as a | + | During his lifetime, Poe was mostly recognized as a literary critic. Fellow critic [[James Russell Lowell]] called him "the most discriminating, philosophical, and fearless critic upon imaginative works who has written in America," though he questioned if he occasionally used [[prussic acid]] instead of [[ink]].<ref>Quinn, 432.</ref> Poe was also known as a writer of [[fiction]] and became one of the first American authors of the nineteenth century to become more popular in Europe than in the United States.<ref name=Meyers258>Meyers, 258.</ref> Poe is particularly respected in [[France]], in part due to early translations by [[Charles Baudelaire]], which became definitive renditions of Poe's work throughout Europe.<ref>Gary Wayne Harner, "Edgar Allan Poe in France: Baudelaire's Labor of Love," Benjamin Franklin Fisher IV (ed.), ''Poe and His Times: The Artist and His Milieu'' (Baltimore, MD: The Edgar Allan Poe Society, 1990, ISBN 0961644923), 218.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Poe's early [[detective fiction]] tales starring the fictitious [[C. Auguste Dupin]] laid the groundwork for future detectives in literature. Sir [[Arthur Conan Doyle]] said, "Each [of Poe's detective stories] is a root from which a whole literature has developed.... Where was the detective story until Poe breathed the breath of life into it?"<ref>Frederick S. Frank and Anthony Magistrale, ''The Poe Encyclopedia'' (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1997, ISBN 0313277680), 103.</ref> The [[Mystery Writers of America]] have named their awards for excellence in the genre the "[[Edgar Award|Edgars]]."<ref> Mark Neimeyer, "Poe and Popular Culture," Kevin J. Hayes (ed.), ''The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe'' (Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0521797276), 206.</ref> Poe's work also influenced [[science fiction]], notably [[Jules Verne]], who wrote a sequel to Poe's novel ''[[The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket]]'' called ''The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, Le sphinx des glaces''.<ref>Frank and Magistrale, 364.</ref> Science fiction author [[H. G. Wells]] noted, "''Pym'' tells what a very intelligent mind could imagine about the south polar region a century ago."<ref>Frank and Magistrale, 372.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Even so, Poe has not received only praise, partly because of the negative perception of his personal character influencing his reputation.<ref name=Meyers258/> [[William Butler Yeats]] was occasionally critical of Poe and once called him "vulgar."<ref>Meyers, 274.</ref> [[Transcendentalism|Transcendentalist]] [[Ralph Waldo Emerson]] reacted to "The Raven" by saying, "I see nothing in it."<ref>Silverman, 265.</ref> [[Aldous Huxley]] wrote that Poe's writing "falls into vulgarity" by being "too poetical" – the equivalent of wearing a diamond ring on every finger.<ref>Aldous Huxley, "Vulgarity in Literature," Robert Regan (ed.), ''Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays'' (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1967), 32.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Preserved homes, landmarks, and museums=== |

| − | + | [[Image:PoeNHS.JPG|thumb|left|upright|200 px|The Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site in Philadelphia is one of several preserved former residences of Poe]] | |

| − | + | No childhood home of Poe is still standing, including the Allan family's Moldavia estate. The oldest standing home in Richmond, the Old Stone House, is in use as the Edgar Allan Poe Museum, though Poe never lived there. The collection includes many items Poe used during his time with the Allan family and also features several rare first printings of Poe works. The dorm room Poe is believed to have used while studying at the University of Virginia in 1826 is preserved and available for visits. Its upkeep is now overseen by a group of students and staff known as the [[Raven Society]].<ref>University of Virginia, [https://aig.alumni.virginia.edu/raven/ The Raven Society]. Retrieved March 5, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | + | The earliest surviving home in which Poe lived is in [[Baltimore]], preserved as the Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum. Poe is believed to have lived in the home at the age of 23 when he first lived with Maria Clemm and Virginia (as well as his grandmother and possibly his brother William Henry Leonard Poe).<ref>Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore, [https://www.eapoe.org/balt/poehse.htm The Baltimore Poe House and Museum] Retrieved March 5, 2020.</ref> It is open to the public and is also the home of the Edgar Allan Poe Society. Of the several homes that Poe, his wife Virginia, and his mother-in-law Maria rented in [[Philadelphia]], only the last house has survived. The Spring Garden home, where the author lived in 1843–1844, is today preserved by the [[National Park Service]] as the Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site.<ref>[https://www.nps.gov/edal/index.htm Edgar Allan Poe] National Historic Site Pennsylvania. Retrieved March 5, 2020.</ref> Poe's final home is preserved as the [[Edgar Allan Poe Cottage]] in the Bronx, New York.<ref name="Poe Cottage"/> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Other Poe landmarks include a building in the [[Upper West Side]], where Poe temporarily lived when he first moved to [[New York City]]. A plaque suggests that Poe wrote "The Raven" there. In [[Boston]] in 2009, the intersection of Charles and Boylston Streets was designated "Edgar Allan Poe Square."<ref> [https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM6AMW_Edgar_Allan_Poe_Square__Boston_MA Edgar Allan Poe Square - Boston, MA] ''Waymarking.com''. Retrieved March 5, 2020.</ref> In 2014, a bronze statue of Stefanie Rocknak's sculpture "Poe Returning to Boston" was unveiled in the square.<ref> Sara Boutorabi, [https://dailyfreepress.com/2014/10/06/edgar-allan-poe-statue-unveiled-boston/ Edgar Allan Poe statue unveiled in Boston] ''The Daily Free Press'', October 6, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | + | ==Poe in popular culture== | |

| − | + | Many of Poe's writings have been adapted into film, for example a notable series featuring [[Vincent Price]] and directed by [[Roger Corman]] in the 1960s, as well as numerous movies and television shows that are based on his life. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The historical Edgar Allan Poe has often appeared as a fictionalized character, often representing the "mad genius" or "tormented artist" and exploiting his personal struggles.<ref>Mark Neimeyer, "Poe and Popular Culture," Kevin J. Hayes (ed.), ''The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe'' (Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0521797276), 209.</ref> Many such depictions also blend in with characters from his stories, suggesting Poe and his characters share identities.<ref>James W. Gargano, "The Question of Poe's Narrators," Robert Regan (ed.), ''Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays'' (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1967), 165.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ==Selected | + | ==Selected list of works== |

| − | |||

{{col-begin}} | {{col-begin}} | ||

{{Col-1-of-2}} | {{Col-1-of-2}} | ||

| − | + | '''Tales''' | |

| − | + | * "[[The Black Cat (short story)|The Black Cat]]" | |

| − | + | * "[[The Cask of Amontillado]]" | |

| − | *"[[The Black Cat (short story)|The Black Cat]]" | + | * "[[A Descent into the Maelstrom]]" |

| − | *"[[The Cask of Amontillado]]" | + | * "[[The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar]]" |

| − | *"[[ | + | * "[[The Fall of the House of Usher]]" |

| − | *"[[The | + | * "[[The Gold-Bug]]" |

| − | *"[[ | + | * "[[Ligeia]]" |

| − | *"[[ | + | * "[[The Masque of the Red Death]]" |

| − | *"[[ | + | * "[[The Murders in the Rue Morgue]]" |

| − | *"[[The Masque of the Red Death]]" | + | * "[[The Oval Portrait]]" |

| − | *"[[The Murders in the Rue Morgue]]" | + | * "[[The Pit and the Pendulum]]" |

| − | *"[[The Pit and the Pendulum]]" | + | * "[[The Premature Burial]]" |

| − | *"[[The | + | * "[[The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether]]" |

| − | *"[[The Tell-Tale Heart]]" | + | * "[[The Tell-Tale Heart]]" |

{{Col-2-of-2}} | {{Col-2-of-2}} | ||

| − | + | '''Poetry''' | |

| − | *"[[Annabel Lee]]" | + | * "[[Al Aaraaf]]" |

| − | *"[[The Bells]]" | + | * "[[Annabel Lee]]" |

| − | *"[[The City in the Sea]]" | + | * "[[The Bells]]" |

| − | *"[[Eldorado (poem)|Eldorado]]" | + | * "[[The City in the Sea]]" |

| − | *"[[The Haunted Palace (poem)|The Haunted Palace]]" | + | * "[[The Conqueror Worm]]" |

| − | *"[[Lenore]]" | + | * "[[A Dream Within A Dream]]" |

| − | *"[[The Raven]]" | + | * "[[Eldorado (poem)|Eldorado]]" |

| − | *"[[Ulalume]]" | + | * "[[Eulalie]]" |

| + | * "[[The Haunted Palace (poem)|The Haunted Palace]]" | ||

| + | * "[[To Helen]]" | ||

| + | * "[[Lenore]]" | ||

| + | * "[[Tamerlane (poem)|Tamerlane]]" | ||

| + | * "[[The Raven]]" | ||

| + | * "[[Ulalume]]" | ||

{{Col-end}} | {{Col-end}} | ||

| + | '''Other works''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | * ''[[Politian (play)|Politian]]'' (1835) – Poe's only play | ||

| + | * ''[[The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket]]'' (1838) – Poe's only complete novel | ||

| + | * "[[The Balloon-Hoax]]" (1844) – A journalistic [[hoax]] printed as a true story | ||

| + | * "[[The Philosophy of Composition]]" (1846) – Essay | ||

| + | * ''[[Eureka: A Prose Poem]]'' (1848) – Essay | ||

| + | * "[[The Poetic Principle]]" (1848) – Essay | ||

| + | * "[[The Light-House]]" (1849) – Poe's last incomplete work | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | *Allen, Hervey (ed.). ''The Works of Edgar Allan Poe''. P. F. Collier & Son, 1927. | |

| − | *Foye, Raymond. ''The Unknown Poe'' | + | *Budd, Louis J, and Edwin H. Cady (eds.). ''On Poe: The Best from American Literature''. Duke University Press Books, 1992. ISBN 978-0822313113 |

| − | *Frank, Frederick S. | + | *Cornelius, Kay, and Harold Bloom. ''Edgar Allan Poe''. Philadelphia, PA: Chelsea House Publishers, 2002. ISBN 978-0791061732 |

| − | * | + | *Fisher, Benjamin Franklin, (ed.). ''Myths and Reality: The Mysterious Mr. Poe''. Baltimore, MD: Edgar Allan Poe Society, 1987. ISBN 978-0961644918 |

| − | * | + | *Fisher, Benjamin Franklin. ''Poe and His Times: The Artist and His Milieu''. Baltimore, MD: Edgar Allan Poe Society, 1990. ISBN 978-0961644925 |

| − | *Quinn, Arthur Hobson. ''Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography'' | + | *Foye, Raymond (ed.). ''The Unknown Poe''. San Francisco, CA: City Lights, 1980. ISBN 0872861104 |

| − | * | + | *Frank, Frederick S. and Anthony Magistrale. ''The Poe Encyclopedia''. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1997. ISBN 0313277680 |

| − | *Silverman, Kenneth. ''Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never- | + | *Hayes, Kevin J. (ed.). ''The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe''. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0521797276 |

| − | * | + | *Hecker, William F. (ed.). ''Private Perry And Mister Poe: The West Point Poems''. Louisiana State University Press, 2005. |

| − | + | *Hoffman, Daniel. ''Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe''. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1998. ISBN 0807123218 | |

| + | *James, Edward, and Farah Mendlesohn (eds.). ''The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction''. Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0521016575 | ||

| + | *Kennedy, J. Gerald (ed.). ''A Historical Guide to Edgar Allan Poe''. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0195121506 | ||

| + | *Krutch, Joseph Wood. ''Edgar Allan Poe: A Study in Genius''. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1926. {{ASIN|B0014JTM8M}} | ||

| + | *Meyers, Jeffrey. ''Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy''. New York, NY: Cooper Square Press, 1992. ISBN 0815410387 | ||

| + | *Quinn, Arthur Hobson. ''Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography''. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1941. ISBN 0801857309 | ||

| + | *Regan, Robert. ''Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays''. Prentice Hall Trade, 1967. ISBN 978-0136849636 | ||

| + | *Rosenheim, Shawn James. ''The Cryptographic Imagination: Secret Writing from Edgar Poe to the Internet''. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0801853326 | ||

| + | *Silverman, Kenneth. ''Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-Ending Remembrance''. New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1991. ISBN 0060923318 | ||

| + | *Sova, Dawn B. ''Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z''. New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2001. ISBN 081604161X | ||

| + | *Walsh, John Evangelist. ''Midnight Dreary: The Mysterious Death of Edgar Allan Poe''. Palgrave Macmillan, 2000. ISBN 978-0312227326 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | All links retrieved | + | All links retrieved February 12, 2024. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * [http://www.nps.gov/edal/ Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site] | |

| − | + | * [http://www.eapoe.org/ Edgar Allan Poe Society in Baltimore] | |

| − | *{{ | + | * {{Find A Grave|id=822}} |

| − | *[http://www. | + | * [http://www.online-literature.com/poe/ Edgar Allan Poe] The Literature Network |

| − | *[http://www.poetryfoundation.org/archive/poet.html?id=81604 Poems by Edgar Allan Poe at PoetryFoundation.org] | + | * [http://www.poemuseum.org/ Poe Museum] in Richmond, Virginia |

| − | *[http://www. | + | * [http://www.blackcatpoems.com/p/edgar_allan_poe.html Poems by Edgar Allan Poe] – An extensive collection of Poe's poetry. |

| − | *[http://www. | + | * [http://www.poetryfoundation.org/archive/poet.html?id=81604 Poems by Edgar Allan Poe at PoetryFoundation.org] |

| − | *[http://www. | + | * [http://www.poestories.com/ PoeStories.com] – With summaries, quotes, and full text of Poe's short stories, a Poe timeline, and image gallery. |

| + | * [http://www.houseofusher.net/ The House of Usher] Edgar Allan Poe Virtual Library | ||

| + | * {{gutenberg author|id=Edgar_Allan_Poe|name=Edgar Allan Poe}} | ||

| + | * [http://www.archive.org/search.php?query=creator%3Aedgar%20poe%20-contributor%3Agutenberg%20AND%20mediatype%3Atexts Works by Edgar Allan Poe], available at Internet Archive. Scanned illustrated books. | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Romanticism}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | }} | ||

| + | [[Category:Biography]] | ||

[[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | [[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | ||

[[Category:Writers and poets]] | [[Category:Writers and poets]] | ||

| − | {{credit1|Edgar_Allen_Poe| | + | {{credit1|Edgar_Allen_Poe|270759715}} |

Latest revision as of 18:07, 12 February 2024

| Edgar Allan Poe | |

|---|---|

1848 daguerreotype of Poe | |

| Born | January 19 1809 Boston, Massachusetts, USA |

| Died | October 7 1849 (aged 40) Baltimore, Maryland, USA |

| Occupation | Poet, short-story writer, editor, literary critic |

| Genres | Horror fiction, crime fiction, detective fiction |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Spouse(s) | Virginia Eliza Clemm Poe |

Edgar Allan Poe (January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American poet, short-story writer, editor and literary critic, and is considered part of the American Romantic Movement. Best known for his tales of mystery and the macabre, Poe was one of the earliest American practitioners of the short story. He is considered the inventor of the detective fiction genre as well as contributing to the emerging genre of science fiction. He was the first well-known American writer to try to earn a living through writing alone, resulting in a financially difficult life and career. Although his poem The Raven, published in January 1845, was highly acclaimed, it brought him little financial reward.

The darkness that characterized many of Poe's writings appears to have roots in his life. Born Edgar Poe in Boston, Massachusetts, he was soon left without parents; John and Frances Allan took him in as a foster child but they never formally adopted him. In 1835, he married Virginia Clemm, his 13-year-old cousin; unfortunately, in 1942 she contracted tuberculosis and died five years later. Her sickness and death took a great toll on Poe. Two years later, at age 40, Poe died in Baltimore under strange circumstances. The cause of his death has remained unknown and has been variously attributed to alcohol, brain congestion, cholera, drugs, heart disease, rabies, suicide, tuberculosis, and other agents.

Poe's works remain popular and influential, both in terms of their style and content. His fascination with death and violence, the loss of a beloved, possibilities of reanimation or life beyond the grave in some physical form, and with macabre and tragic mysteries continue to intrigue readers worldwide, reflecting human interest in life after death and desire for the revealing of truth. His interest and works in areas such as cosmology and cryptography showed an intuitive intelligence with ideas ahead of his time. Poe continues to appear throughout popular culture in literature, music, films, and television.

Life

Early life

Edgar Poe was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on January 19, 1809, the second child of actress Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins Poe and actor David Poe, Jr. He had an elder brother, William Henry Leonard Poe, and a younger sister, Rosalie Poe.[1] His father abandoned their family in 1810, and his mother died a year later from consumption. Poe was then taken into the home of John Allan, a successful Scottish merchant in Richmond, Virginia, who dealt in a variety of goods including tobacco, cloth, wheat, tombstones, and slaves.[2] The Allans served as a foster family but never formally adopted him,[3] although they gave him the name "Edgar Allan Poe."[4]

The Allan family had Poe baptized in the Episcopal Church in 1812. John Allan alternately spoiled and aggressively disciplined his foster son.[4] The family, including Poe and Allan's wife, Frances Valentine Allan, sailed to England in 1815. Poe attended the grammar school in Irvine, Scotland (where John Allan was born) for a short period in 1815, before rejoining the family in London in 1816. He studied at a boarding school in Chelsea until summer 1817. He was subsequently entered at the Reverend John Bransby’s Manor House School at Stoke Newington, then a suburb four miles (6 km) north of London.[5]

Poe moved back with the Allans to Richmond, Virginia in 1820. In March 1825, John Allan's uncle[6] and business benefactor William Galt, said to be one of the wealthiest men in Richmond, died and left Allan several acres of real estate. The inheritance was estimated at $750,000. By summer 1825, Allan celebrated his expansive wealth by purchasing a two-story brick home named Moldavia.[7] Poe may have become engaged to Sarah Elmira Royster before he registered at the one-year-old University of Virginia in February 1826 to study languages.[8] Although he excelled in his studies, during his time there Poe lost touch with Royster and also became estranged from his foster father over gambling debts and his foster father's refusal to cover all his expenses. Poe withdrew permanently from the school after only one year of study, and, not feeling welcome in Richmond, especially when he learned that his sweetheart Royster had married Alexander Shelton, he traveled to Boston in April 1827, sustaining himself with odd jobs as a clerk and newspaper writer.[9] At some point he started using the pseudonym Henri Le Rennet.[10] That same year, he released his first book, a 40-page collection of poetry, Tamerlane and Other Poems, attributed with the byline "by a Bostonian." Only 50 copies were printed, and the book received virtually no attention.[11]

Military career

Unable to support himself, on May 27, 1827, Poe enlisted in the United States Army as a private. Using the name "Edgar A. Perry," he claimed he was 22 years old even though he was 18.[12] He first served at Fort Independence in Boston Harbor.[9] Poe's regiment was then posted to Fort Moultrie in Charleston, South Carolina and traveled there by ship on the brig Waltham on November 8, 1827. Poe was promoted to "artificer," an enlisted tradesman who prepared shells for artillery, and had his monthly pay doubled.[13] After serving for two years and attaining the rank of Sergeant Major for Artillery (the highest rank a non-commissioned officer can achieve), Poe sought to end his five-year enlistment early. He revealed his real name and his circumstances to his commanding officer, Lieutenant Howard. Howard would allow Poe to be discharged only if he reconciled with John Allan. His foster mother, Frances Allan, died on February 28, 1829, and Poe visited the day after her burial. Perhaps softened by his wife's death, John Allan agreed to support Poe's attempt to be discharged in order to receive an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point.[14]

Poe was discharged on April 15, 1829, after securing a replacement to finish his enlisted term for him.[15] Before entering West Point, Poe moved back to Baltimore for a time, to stay with his widowed aunt Maria Clemm, her daughter, Virginia Eliza Clemm (Poe's first cousin), his brother Henry, and his invalid grandmother Elizabeth Cairnes Poe.[12] Meanwhile, Poe published his second book, Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane and Minor Poems, in Baltimore in 1829.[16]

Poe traveled to West Point and matriculated as a cadet on July 1, 1830.[17] In October 1830, John Allan married his second wife, Louisa Patterson.[12] The marriage, and bitter quarrels with Poe over the children born to Allan out of affairs, led to the foster father finally disowning Poe.[18] Poe decided to leave West Point by purposely getting court-martialed. On February 8, 1831, he was tried for gross neglect of duty and disobedience of orders for refusing to attend formations, classes, or church. Poe tactically pled not guilty to induce dismissal, knowing he would be found guilty.[19]

He left for New York in February 1831, and released a third volume of poems, simply titled Poems. The book was financed with help from his fellow cadets at West Point; they may have been expecting verses similar to the satirical ones Poe had been writing about commanding officers.[20] Printed by Elam Bliss of New York, it was labeled as "Second Edition" and included a page saying, "To the U.S. Corps of Cadets this volume is respectfully dedicated." The book once again reprinted the long poems "Tamerlane" and "Al Aaraaf" but also six previously unpublished poems including early versions of "To Helen," "Israfel," and "The City in the Sea".[21] He returned to Baltimore, to his aunt, brother and cousin, in March 1831. His elder brother Henry, who had been in ill health in part due to problems with alcoholism, died on August 1, 1831.[22]

Marriage

Poe secretly married Virginia, his cousin, on September 22, 1835. She was 13 at the time, though she is listed on the marriage certificate as being 21.[23] On May 16, 1836, they had a second wedding ceremony in Richmond, this time in public.[24]

One evening in January 1842, Virginia showed the first signs of consumption, now known as tuberculosis, while singing and playing the piano. Poe described it as breaking a blood vessel in her throat.[25] She only partially recovered, and Poe began to drink more heavily under the stress of his wife's illness. In 1946, Poe moved to a cottage in the Fordham section of The Bronx, New York. Virginia died there on January 30, 1847.[26]

Increasingly unstable after his wife's death, Poe attempted to court the poet Sarah Helen Whitman, who lived in Providence, Rhode Island. Their engagement failed, purportedly because of Poe's drinking and erratic behavior. However, there is also evidence that Whitman's mother intervened and did much to derail their relationship.[27] Poe then returned to Richmond and resumed a relationship with his childhood sweetheart, Sarah Elmira Royster, whose husband had died in 1944.[28]

Death

On October 3, 1849, Poe was found on the streets of Baltimore delirious, "in great distress, and... in need of immediate assistance," according to the man who found him, Joseph W. Walker.[29] He was taken to the Washington College Hospital, where he died on Sunday, October 7, 1849.[30] Poe was never coherent long enough to explain how he came to be in his dire condition, and, oddly, was wearing clothes that were not his own. All medical records, including his death certificate, have been lost.[31]

Newspapers at the time reported Poe's death as "congestion of the brain" or "cerebral inflammation," common euphemisms for deaths from disreputable causes such as alcoholism; the actual cause of his death, however, remains a mystery.[32] From as early as 1872, cooping (a practice in the United States by which unwilling participants were forced to vote multiple times for a particular candidate in an election; they were given alcohol or drugs in order for them to comply) was commonly believed to have been the cause,[33] and speculation has included delirium tremens, heart disease, epilepsy, syphilis, meningeal inflammation,[34] cholera, brain tumor, and even rabies as medical causes; murder has also been suggested.[35] [33]

Career

Poe was the first well-known American author and poet to try to live on his writing alone.[36][37] He chose a difficult time in American publishing to do so.[38] He was hampered by the lack of an international copyright law.[39] Publishers often pirated copies of British works rather than paying for new work by Americans.[37] The industry was also particularly hurt by the Panic of 1837.[38] Despite a booming growth in American periodicals around this time period, fueled in part by new technology, many did not last beyond a few issues[40] and publishers often refused to pay their writers or paid them much later than they promised.[38] As a result Poe, throughout his attempts at pursuing a successful literary career, was forced to constantly make humiliating pleas for money and other assistance.[41]

After his early attempts at poetry, Poe turned his attention to prose. He placed a few stories with a Philadelphia publication and began work on his only drama, Politian. The Saturday Visitor, a Baltimore paper, awarded Poe a prize in October 1833 for his short story "MS. Found in a Bottle".[42] The story brought him to the attention of John P. Kennedy, a Baltimorian of considerable means. He helped Poe place some of his stories, and introduced him to Thomas W. White, editor of the Southern Literary Messenger in Richmond. Poe became assistant editor of the periodical in August 1835;[43] however, within a few weeks, he was discharged after repeatedly being found drunk.[44] Reinstated by White after promising good behavior, Poe went back to Richmond with Virginia and her mother. He remained at the Messenger until January 1837, publishing several poems, book reviews, criticism, and stories in the paper. During this period, its circulation increased from 700 to 3,500.[1]

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym was published and widely reviewed in 1838. In the summer of 1839, Poe became assistant editor of Burton's Gentleman's Magazine. He published numerous articles, stories, and reviews, enhancing his reputation as a trenchant critic that he had established at the Southern Literary Messenger. Also in 1839, the collection Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque was published in two volumes, though it made him little money received mixed reviews.[45] Poe left Burton's after about a year and found a position as assistant at Graham's Magazine.[46]

In June 1840, Poe published a prospectus announcing his intentions to start his own journal, The Stylus.[47] Originally, Poe intended to call the journal The Penn, as it would have been based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In the June 6, 1840 issue of Philadelphia's Saturday Evening Post, Poe bought advertising space for his prospectus: "Prospectus of the Penn Magazine, a Monthly Literary journal to be edited and published in the city of Philadelphia by Edgar A. Poe."[48] The journal would never be produced before Poe's death.

He left Graham's and attempted to find a new position, for a time angling for a government post. He returned to New York, where he worked briefly at the Evening Mirror before becoming editor of the Broadway Journal and, later, sole owner.[49] There he alienated himself from other writers by publicly accusing Henry Wadsworth Longfellow of plagiarism, though Longfellow never responded.[50] On January 29, 1845, his poem "The Raven" appeared in the Evening Mirror and became a popular sensation. Though it made Poe a household name almost instantly,[51] he was paid only $9 for its publication.[52] The Broadway Journal failed in 1846.[49]

Literary style and themes

Genres

Poe's best known fiction works are Gothic,[53] a genre he followed to appease the public taste.[54] Many of his works are generally considered part of the dark romanticism genre, a literary reaction to transcendentalism, which Poe strongly disliked.[55] He referred to followers of that movement as "Frogpondians" after the pond on Boston Common.[54] and ridiculed their writings as "metaphor-run," lapsing into "obscurity for obscurity's sake" or "mysticism for mysticism's sake."[55]

Poe described many of his works as "tales of ratiocination"[56] in which the primary concern of the plot is ascertaining truth, and the means of obtaining the truth is a complex and mysterious process combining intuitive logic, astute observation, and perspicacious inference. Such stories, especially those featuring the fictional detective, C. Auguste Dupin, laid the groundwork for future detectives in literature.

Much of Poe's poetry and prose features his characteristic interest in exploring the psychology of man, including the perverse and self-destructive nature of the conscious and subconscious mind which leads to insanity. His most recurring themes deal with questions of death, including its physical signs, the effects of decomposition, concerns of premature burial, the reanimation of the dead, and mourning.[57] Biographers and critics have often suggested that Poe's frequent theme of the "death of a beautiful woman" stems from the repeated loss of women throughout his life, including his wife.[58] Some of Poe’s notable dark romantic works include the short stories "Ligeia" and "The Fall of the House of Usher" and poems "The Raven" and "Ulalume."

Poe's works often feature an unnamed narrator and the tale or poem tracks his descent into madness. For example, the narrator of Poe's classic Gothic short story, The Tell-Tale Heart, endeavors to convince the reader of his sanity, while describing a murder he committed. The murder is carefully calculated, and the murderer dismembered the body and hid it under the floorboards. Ultimately the narrator's guilt manifests itself in an auditory hallucination: The narrator hears the man's heart still beating under the floorboards. Poe's poem The Raven is often noted for its musicality, stylized language, and supernatural atmosphere. It tells of a talking raven's mysterious visit to an unnamed narrator, tracing his slow fall into madness. The narrator is distraught, lamenting the loss of his love, Lenore. The raven seems to further instigate his distress with its constant repetition of the word "Nevermore."

Beyond horror, Poe also wrote satires, humor tales, and hoaxes. For comic effect, he used irony and ludicrous extravagance, often in an attempt to liberate the reader from cultural conformity.[54] In fact, "Metzengerstein," the first story that Poe is known to have published,[59] and his first foray into horror, was originally intended as a burlesque satirizing the popular genre.[60] Poe also contributed to the emerging genre of science fiction, responding in his writing to emerging technologies such as hot air balloons in "The Balloon-Hoax".[61][62]

Poe wrote much of his work using themes specifically catered for mass market tastes.[38] To that end, his fiction often included elements of popular pseudosciences such as phrenology[63] and physiognomy.[64]

Literary theory

Poe's writing reflects his literary theories, which he presented in his criticism and also in essays such as "The Poetic Principle."[65] He disliked didacticism[66] and allegory,[67] though he believed that meaning in literature should be an undercurrent just beneath the surface. Works with obvious meanings, he wrote, cease to be art.[68] He believed that quality work should be brief and focus on a specific single effect.[65] To that end, he believed that the writer should carefully calculate every sentiment and idea.[69] In "The Philosophy of Composition," an essay in which Poe describes his method in writing "The Raven," he claims to have strictly followed this method.

Cryptography

Poe had a keen interest in the field of cryptography. He had placed a notice of his abilities in the Philadelphia paper Alexander's Weekly (Express) Messenger, inviting submissions of ciphers, which he proceeded to solve.[70] In July 1841, Poe had published an essay called "A Few Words on Secret Writing" in Graham's Magazine. Realizing the public interest in the topic, he wrote "The Gold-Bug" incorporating ciphers as part of the story.[71] Poe's success in cryptography relied not so much on his knowledge of that field (his method was limited to the simple substitution cryptogram), as on his knowledge of the magazine and newspaper culture. His keen analytical abilities, which were so evident in his detective stories, allowed him to see that the general public was largely ignorant of the methods by which a simple substitution cryptogram can be solved, and he used this to his advantage.[70] The sensation Poe created with his cryptography stunt played a major role in popularizing cryptograms in newspapers and magazines.[72]

The effect of Poe's interest in cryptography extended beyond increasing public interest in his lifetime. William Friedman, America's foremost cryptologist, was initially interest in cryptography after reading "The Gold-Bug" as a child —an interest he later put to use in deciphering Japan's PURPLE code during World War II.[73]

Physics and cosmology

Eureka: A Prose Poem, an essay written in 1848, was subtitled "An Essay on the Material and Spiritual Universe" and included a cosmological theory that presaged the big bang theory by 80 years.[74] Adapted from a lecture he had presented on February 3, 1848 entitled "On The Cosmography of the Universe" at the Society Library in New York, Eureka describes Poe's intuitive conception of the nature of the universe. Poe eschewed the scientific method in Eureka and instead wrote from pure intuition. For this reason, he considered it a work of art, not science,[75]

Eureka was received poorly in Poe's day and generally described as absurd, even by friends. It is full of scientific errors. In particular, Poe's suggestions opposed Newtonian principles regarding the density and rotation of planets.[76] Nevertheless, he considered it to be his career masterpiece.[77]

Legacy

Griswold's "Memoir"

The day Edgar Allan Poe was buried, a long obituary appeared in the New York Tribune signed "Ludwig." It was soon published throughout the country. The piece began, "Edgar Allan Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it."[78] "Ludwig" was soon identified as Rufus Wilmot Griswold, an editor, critic, and anthologist who had borne a grudge against Poe since 1842.

Griswold somehow became Poe's literary executor and attempted to destroy his enemy's reputation after his death.[79] He wrote a biographical article of Poe called "Memoir of the Author," which he included in an 1850 volume of the collected works. Griswold depicted Poe as a depraved, drunk, drug-addled madman and included Poe's letters as evidence.[79] These letters were later revealed as forgeries.[80] In fact, many of his claims were either outright lies or distorted half-truths. For example, it is now known that Poe was not a drug addict.[81] Griswold's book was denounced by those who knew Poe well,[82] but it became a popularly accepted one, in part because it was the only full biography available and in part because readers thrilled at the thought of reading works by an "evil" man.[83]

Poe Toaster

Adding to the mystery surrounding Poe's death, an unknown visitor affectionately referred to as the "Poe Toaster" has paid homage to Poe's grave every year since 1949. As the tradition has been carried on for more than 50 years, it is likely that the "Poe Toaster" is actually several individuals; however, the tribute is always the same. Every January 19, in the early hours of the morning, a figure dressed in black lays three roses and a bottle of cognac at the Poe's original grave marker. Members of the Edgar Allan Poe Society in Baltimore have helped in protecting this tradition for decades.

On August 15, 2007, Sam Porpora, a former historian at the Westminster Church in Baltimore where Poe is buried, claimed that he had started the tradition in the 1960s. The claim that the tradition began in 1949, he said, was a hoax in order to raise money and enhance the profile of the church. His story has not been confirmed, and some details he has given to the press have been pointed out as factually inaccurate.[84]

Literary influence

During his lifetime, Poe was mostly recognized as a literary critic. Fellow critic James Russell Lowell called him "the most discriminating, philosophical, and fearless critic upon imaginative works who has written in America," though he questioned if he occasionally used prussic acid instead of ink.[85] Poe was also known as a writer of fiction and became one of the first American authors of the nineteenth century to become more popular in Europe than in the United States.[86] Poe is particularly respected in France, in part due to early translations by Charles Baudelaire, which became definitive renditions of Poe's work throughout Europe.[87]

Poe's early detective fiction tales starring the fictitious C. Auguste Dupin laid the groundwork for future detectives in literature. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle said, "Each [of Poe's detective stories] is a root from which a whole literature has developed.... Where was the detective story until Poe breathed the breath of life into it?"[88] The Mystery Writers of America have named their awards for excellence in the genre the "Edgars."[89] Poe's work also influenced science fiction, notably Jules Verne, who wrote a sequel to Poe's novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket called The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, Le sphinx des glaces.[90] Science fiction author H. G. Wells noted, "Pym tells what a very intelligent mind could imagine about the south polar region a century ago."[91]

Even so, Poe has not received only praise, partly because of the negative perception of his personal character influencing his reputation.[86] William Butler Yeats was occasionally critical of Poe and once called him "vulgar."[92] Transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson reacted to "The Raven" by saying, "I see nothing in it."[93] Aldous Huxley wrote that Poe's writing "falls into vulgarity" by being "too poetical" – the equivalent of wearing a diamond ring on every finger.[94]

Preserved homes, landmarks, and museums

No childhood home of Poe is still standing, including the Allan family's Moldavia estate. The oldest standing home in Richmond, the Old Stone House, is in use as the Edgar Allan Poe Museum, though Poe never lived there. The collection includes many items Poe used during his time with the Allan family and also features several rare first printings of Poe works. The dorm room Poe is believed to have used while studying at the University of Virginia in 1826 is preserved and available for visits. Its upkeep is now overseen by a group of students and staff known as the Raven Society.[95]

The earliest surviving home in which Poe lived is in Baltimore, preserved as the Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum. Poe is believed to have lived in the home at the age of 23 when he first lived with Maria Clemm and Virginia (as well as his grandmother and possibly his brother William Henry Leonard Poe).[96] It is open to the public and is also the home of the Edgar Allan Poe Society. Of the several homes that Poe, his wife Virginia, and his mother-in-law Maria rented in Philadelphia, only the last house has survived. The Spring Garden home, where the author lived in 1843–1844, is today preserved by the National Park Service as the Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site.[97] Poe's final home is preserved as the Edgar Allan Poe Cottage in the Bronx, New York.[26]

Other Poe landmarks include a building in the Upper West Side, where Poe temporarily lived when he first moved to New York City. A plaque suggests that Poe wrote "The Raven" there. In Boston in 2009, the intersection of Charles and Boylston Streets was designated "Edgar Allan Poe Square."[98] In 2014, a bronze statue of Stefanie Rocknak's sculpture "Poe Returning to Boston" was unveiled in the square.[99]

Poe in popular culture

Many of Poe's writings have been adapted into film, for example a notable series featuring Vincent Price and directed by Roger Corman in the 1960s, as well as numerous movies and television shows that are based on his life.

The historical Edgar Allan Poe has often appeared as a fictionalized character, often representing the "mad genius" or "tormented artist" and exploiting his personal struggles.[100] Many such depictions also blend in with characters from his stories, suggesting Poe and his characters share identities.[101]

Selected list of works

|

Tales

|

Poetry

|

Other works

- Politian (1835) – Poe's only play

- The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838) – Poe's only complete novel

- "The Balloon-Hoax" (1844) – A journalistic hoax printed as a true story

- "The Philosophy of Composition" (1846) – Essay

- Eureka: A Prose Poem (1848) – Essay

- "The Poetic Principle" (1848) – Essay

- "The Light-House" (1849) – Poe's last incomplete work

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hervey Allen, "Introduction," The Works of Edgar Allan Poe (New York, NY: P. F. Collier & Son, 1927).

- ↑ Jeffrey Meyers, Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy (New York, NY: Cooper Square Press, 1992, ISBN 0815410387), 8.

- ↑ Arthur Hobson Quinn, Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography (New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc., 1941, ISBN 0801857309), 61.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Meyers, 9.

- ↑ Kenneth Silverman, Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-Ending Remembrance (New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1991, ISBN 0060923318), 16–18.

- ↑ Meyers, 20.

- ↑ Silverman, 27–28.

- ↑ Silverman, 29–30.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Meyers, 32.

- ↑ Silverman, 41.

- ↑ Meyers, 33–34.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Kay Cornelius, "Biography of Edgar Allan Poe," Harold Bloom (ed.) Bloom's BioCritiques: Edgar Allan Poe (Philadelphia, PA: Chelsea House Publishers, 2002, ISBN 0791061736), 13-14.

- ↑ Meyers, 35.

- ↑ Silverman, 43–47.

- ↑ Meyers, 38.

- ↑ Dawn B. Sova, Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z (New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2001, ISBN 081604161X), 5.