Dragon

The dragon is a mythical creature typically depicted as a large and powerful serpent or other reptile with magical or spiritual qualities. Mythological creatures possessing some or most of the characteristics typically associated with dragons are common throughout the world's cultures.[1] It is well known that there is a negative image in the western world of the dragon, but in East Asia, especially in China, the dragon has a positive image and is a benevolent god.

Overview

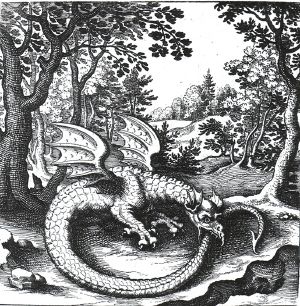

Dragons are commonly portrayed as serpentine or reptilian, hatching from eggs and possessing extremely large, typically scaly, bodies; they are sometimes portrayed as having large eyes, a feature that is the origin for the word for dragon in many cultures, and are often (but not always) portrayed with wings and a fiery breath. Some dragons do not have wings at all, but look more like long snakes. Dragons can have a variable number of legs: none, two, four, or more when it comes to early European literature. Modern depictions of dragons are very large in size, but some early European depictions of dragons were only the size of bears, or, in some cases, even smaller, around the size of a butterfly.

Although dragons (or dragon-like creatures) occur commonly in legends around the world, different cultures have perceived them differently. Chinese dragons (Simplified Chinese: 龙; Traditional Chinese: 龍; pinyin: lóng), and Eastern dragons generally, are usually seen as benevolent, whereas European dragons are usually malevolent (there are of course exceptions to these rules). Malevolent dragons also occur in Persian mythology (see Azhi Dahaka) and other cultures.

Dragons are particularly popular in China. Along with the phoenix, the dragon was a symbol of the Chinese emperors. Dragon costumes manipulated by several people are a common sight at Chinese festivals.

Dragons are often held to have major spiritual significance in various religions and cultures around the world. In many Eastern and Native American cultures dragons were, and in some cultures still are, revered as representative of the primal forces of nature and the universe. They are associated with wisdom—often said to be wiser than humans—and longevity. They are commonly said to possess some form of magic or other supernormal power, and are often associated with wells, rain, and rivers. In some cultures, they are said to be capable of human speech. They are also said to be able to talk to all animals and converse with humans.

Dragons are very popular characters in fantasy literature, role-playing games and video games today.

The term dragoon, for infantry that move around by horse yet still fight as foot soldiers, is derived from their early firearm, the "dragon", a wide-bore musket that spat flame when it fired, and was thus named for the mythical beast.

Symbolism

In medieval symbolism, dragons were often symbolic of apostasy and treachery, but also of anger and envy, and eventually symbolized great calamity. Several heads were symbolic of decadence and oppression, and also of heresy. They also served as symbols for independence, leadership and strength. Many dragons also represent wisdom; slaying a dragon not only gave access to its treasure hoard, but meant the hero had bested the most cunning of all creatures. In some cultures, especially Chinese, or around the Himalayas, dragons are considered to represent good luck.

Joseph Campbell in the The Power of Myth viewed the dragon as a symbol of divinity or transcendence because it represents the unity of Heaven and Earth by combining the serpent form (earthbound) with the bat/bird form (airborne).

Dragons embody both male and female traits as in the example from Aboriginal myth that raises baby humans to adulthood training them for survival in the world (Littleton, 2002, p. 646). Another contrast in the way dragons are portrayed is their ability to breathe fire but live in the ocean—water and fire together. And like in the quote from Joseph Campbell above, they also include the opposing elements of earth and sky. Dragons represent the joining of the opposing forces of the cosmos.

Yet another symbolic view of dragons is the Ouroborus, or the dragon encircling and eating its own tail. When shaped like this the dragon becomes a symbol of eternity, natural cycles, and completion.

In Christianity

The Latin word for a dragon, draco (genitive: draconis), actually means snake or serpent, emphasizing the European association of dragons with snakes. The Medieval Biblical interpretation of the Devil being associated with the serpent who tempted Adam and Eve, thus gave a snake-like dragon connotations of evil. Generally speaking, Biblical literature itself did not portray this association (save for the Book of Revelation, whose treatment of dragons is detailed below). The demonic opponents of God, Christ, or good Christians have commonly been portrayed as reptilian or chimeric.

In the Book of Job Chapter 41, the sea monster Leviathan, which has some dragon-like characteristics.

In Revelation 12:3, an enormous red beast with seven heads is described, whose tail sweeps one third of the stars from heaven down to earth (held to be symbolic of the fall of the angels, though not commonly held among biblical scholars). In most translations, the word "dragon" is used to describe the beast, since in the original Greek the word used is drakon (δράκον).

In iconography, some Catholic saints are depicted in the act of killing a dragon. This is one of the common aspects of Saint George in Egyptian Coptic iconography [1], on the coat of arms of Moscow, and in English and Catalan legend. In Italy, Saint Mercurialis, first bishop of the city of Forlì, is also depicted slaying a dragon.[2] Saint Julian of Le Mans, Saint Veran, Saint Crescentinus, and Saint Leonard of Noblac were also venerated as dragon-slayers.

However, some say that dragons were good, before they fell, as humans did. Also contributing to the good dragon argument in Christianity is the fact that, if they did exist, they were created as were any other creature, as seen in Dragons In Our Midst, a contemporary Christian book series by author Bryan Davis.

Chinese zodiac

The years 1916, 1928, 1940, 1952, 1964, 1976, 1988, 2000, 2012, 2024, 2036, 2048, 2060 are considered the Year of the Dragon in the Chinese zodiac.

The Chinese zodiac purports that people born in the Year of the Dragon are healthy, energetic, excitable, short-tempered, and stubborn. They are also supposedly honest, sensitive, brave, and inspire confidence and trust. The Chinese zodiac purports that Dragon people are the most eccentric of any in the eastern zodiac. They supposedly neither borrow money nor make flowery speeches, but tend to be soft-hearted which sometimes gives others an advantage over them. They are purported to be compatible with Rats, Snakes, Monkeys, and Roosters.

In East Asia

Dragons are commonly symbols of good luck or health in some parts of Asia, and are also sometimes worshipped. Asian dragons are considered as mythical rulers of weather, specifically rain and water, and are usually depicted as the guardians of flaming pearls.

In China, as well as in Japan and Korea, the Azure Dragon is one of the Four Symbols of the Chinese constellation, representing spring (season), the element of Wood and the east. Chinese dragons are often shown with large pearls in their grasp, though some say that it is really the dragon's egg. The Chinese believed that the dragons lived under water most of the time, and would sometimes offer rice as a gift to the dragons. The dragons were not shown with wings like the European dragons because it was believed they could fly using magic.

A Yellow dragon (Huang long) with five claws on each foot, on the other hand, represents the change of seasons, the element of Earth (the Chinese 'fifth element') and the center. Furthermore, it symbolizes imperial authority in China, and indirectly the Chinese people as well. Chinese people often use the term "Descendants of the Dragon" as a sign of ethnic identity. The dragon is also the symbol of royalty in Bhutan (whose sovereign is known as Druk Gyalpo, or Dragon King).

In Vietnam, the dragon (Vietnamese: rồng) is the most important and sacred symbol. According to the ancient creation myth of the Kinh people, all Vietnamese people are descended from dragons through Lạc Long Quân, who married Âu Cơ, a fairy. The eldest of their 100 sons founded the first dynasty of Hùng Vương Emperors.

History and origins of dragons

Template:Cleanup-date

Where the original concept of a dragon came from is unknown, as there is no accepted scientific theory or any evidence to support that dragons actually exist or have existed.

Some believe that the dragon may have had a real-life counterpart from which the legends around the world arose — typically dinosaurs or other archosaurs are mentioned as a possibility — but there is no physical evidence to support this claim, only alleged sightings collected by cryptozoologists. In a common variation of this hypothesis, giant lizards such as Megalania are substituted for the living dinosaurs. Some Creationists hold that dragons are just an exaggerated depiction of what we now call dinosaurs and that humans and dinosaurs (dragons) did co-exist.[2] All of these hypotheses are widely considered to be pseudoscience or myth.

Dinosaur fossils were once thought of as "dragon bones" — a discovery in 300 B.C.E. in Wucheng, Sichuan, China, was labeled as such by Chang Qu.[3] It is unlikely, however, that these finds alone prompted the legends of flying monsters, but may have served to reinforce them.

Herodotus, often called the "father of history", visited Judea c.450 B.C.E. and wrote that he heard of caged dragons in nearby Arabia, near Petra, Jordan. Curious, he travelled to the area and found many skeletal remains of serpents and mentioned reports of flying serpents flying from Arabia into Egypt but being fought off by Ibises Histories. Histories (Greek). Retrieved 2006-06-14..

According to Marco Polo's journals, Polo was walking through Anatolia into Persia and came upon real live flying dragons that attacked his party caravan in the desert and he reported that they were very frightening beasts that almost killed him in an attack.[citation needed] Polo did not write his journals down — they were dictated to his cellmate in prison, and there is much dispute over whether this writer may have invented the dragon to embellish the tale.[citation needed] Polo was also the first western man to describe Chinese "dragon bones" with early writing on them. These bones were presumably either fossils (as described by Chang Qu) or the bones of other animals.[citation needed] Reference: Il Milione

It has also been suggested by proponents of catastrophism that comets or meteor showers gave rise to legends about fiery serpents in the sky.[citation needed] In Old English, comets were sometimes called fyrene dracan or fiery dragons. Volcanic eruptions may have also been responsible for reinforcing the belief in dragons, although instances in Europe and asian countries were rare.

In Hindu mythology, Manasa and Vasuki are serpent like creatures associated with the dragon. [3] Indra, is the hindu storm god who slays Vritra, a large serpent like creature on a mountain.

The Vietnamese dragon is the combined image of crocodile, snake, lizard and bird. Historically, Vietnamese people lived near rivers, so they venerated crocodiles as "Giao Long", the first kind of Vietnamese dragon. Then, many kinds of dragon were developed in architecture, painting, literature and Vietnamese consciousness.

In Greek mythology there are many snake or dragon legends, usually in which a serpent or dragon guards some treasure. The first Pelasgian kings of Athens were said to be half human, half snake. The dragon Ladon guarded the Golden Apples of the Sun of the Hesperides. Another serpentine dragon guarded the Golden Fleece, protecting it from theft by Jason and the Argonauts. Similarly, Pythia and Python, a pair of serpents, guarded the temple of Gaia and the Oracular priestess, before the Delphic Oracle was seized by Apollo and the two serpents were draped around his winged caduceus, which he then gave to Hermes.

The Greek myths of Hercules and Ladon and others are believed to be based upon earlier from Canaanite myth where Baal overcame Lotan, and Israelite Yahweh overcame Leviathan. These stories too go back still further in history 1,500 B.C.E., to the Hittite or Hurrian hero Kumarbi who had to overcome the dragon Illuyankas of the Sea.

In Australian Aboriginal mythology, the Rainbow Serpent was a culture hero in many parts of the country. Known by different names in different places, from the Waugal of the South Western Nyungar, to the Ganba of the North Central Deserts or the Wanambee of South Australia, the rainbow serpent, associated with the creation of waterholes and river courses, was to be feared and respected.

Recently, the Discovery Channel ran a programme titled Dragons: A Fantasy Made Real. The programme tries to look at plausible scientific explanations to assume a "what if" scenario, putting various theories and portraying dragons as if they had existed.[4]

European dragons

In European folklore, a dragon is a serpentine legendary creature. The Latin word draco, as in the constellation Draco, comes directly from Greek δράκων, drákōn. The word for dragon in Germanic mythology and its descendants is worm (Old English: wyrm, Old High German: wurm, Old Norse: ormr), meaning snake or serpent. In Old English wyrm means "serpent", draca means "dragon". Finnish lohikäärme means directly "salmon-snake", but the word lohi- was originally louhi- meaning crags or rocks, a "mountain snake". Though a winged creature, the dragon is generally to be found in its underground lair, a cave that identifies it as an ancient creature of earth. Likely, the dragons of European and Mid Eastern mythology stem from the cult of snakes found in religions throughout the world.

The dragon of the modern period is typically depicted as a huge fire-breathing, scaly and horned dinosaur-like creature, with leathery wings, with four legs and a long muscular tail. It is sometimes shown with feathered wings, crests, fiery manes, and various exotic colorations. Iconically it has at last combined the Chinese dragon with the western one. Asian dragons are long serpent like creatures which possess the scales of a carp, horns of a deer, feet of an eagle, the body of a snake, a feathery mane, large eyes, and can be holding a pearl to control lightning. They usually have no wings. Imperial dragons that were sewn on to silk had five claws (for a king), or four for a prince, or three for courtiers of a lower ranking. The dragons were bringers of rain and lived in and governed bodies of water (e.g lakes, rivers, oceans, or seas). Asian dragons were benevolent, but bossy (this strict behavior is why one of China's nicknames is "the Dragon"). In Western folklore, dragons are usually portrayed as evil, with exceptions mainly in modern fiction.

Many modern stories represent dragons as extremely intelligent creatures who can talk, associated with (and sometimes in control of) powerful magic. Dragon's blood often has magical properties: for example it let Siegfried understand the language of the Forest Bird. The typical dragon protects a cavern or castle filled with gold and treasure and is often associated with a great hero who tries to slay it, but dragons can be written into a story in as many ways as a human character. This includes the monster being used as a wise being whom heroes could approach for help and advice.

Roman dragons

Roman dragons evolved from serpentine Greek ones, combined with the dragons of the Near East, in the mix that characterized the hybrid Greek/Eastern Hellenistic culture. From Babylon, the musrussu was a classic representation of a Near Eastern dragon. John's Book of Revelation — Greek literature, not Roman — describes Satan as "a great dragon, flaming red, with seven heads and ten horns". Much of John's literary inspiration is late Hebrew and Greek, but John's dragon, like his Satan, are both more likely to have come originally through the Near East. Perhaps the distinctions between dragons of western origin and Chinese dragons (q.v.) are arbitrary. A later Roman dragon was certainly of Iranian origin: in the Roman Empire, where each military cohort had a particular identifying signum, (military standard), after the Dacian Wars and Parthian War of Trajan in the east, the Draco military standard entered the Legion with the Cohors Sarmatarum and Cohors Dacorum (Sarmatian and Dacian cohort) — a large dragon fixed to the end of a lance, with large gaping jaws of silver and with the rest of the body formed of colored silk. With the jaws facing into the wind, the silken body inflated and rippled, resembling a windsock. This signum is described in Vegetius Epitoma Rei Militaris, 379 C.E. (book ii, ch XIII. 'De centuriis atque vexillis peditum'):

Dragons in Slavic mythology

Dragons of Slavic mythology hold mixed temperaments towards humans. For example, dragons (дракон, змей, ламя) in Bulgarian mythology are either male or female, each gender having a different view of mankind. The female dragon and male dragon, often seen as brother and sister, represent different forces of agriculture. The female dragon represents harsh weather and is the destroyer of crops, the hater of mankind, and is locked in a never ending battle with her brother. The male dragon protects the humans' crops from destruction and is generally loving to humanity. Fire and water play major roles in Bulgarian dragon lore; the female has water characteristics, whilst the male is usually a fiery creature. In Bulgarian legend, dragons are three headed, winged beings with snake's bodies.

In Russian, Belarusian, and Ukrainian lore, a dragon, or zmey (Russian), smok (Belarussian) zmiy (Ukrainian), is generally an evil, four-legged beast with few if any redeeming qualities. Zmeys are intelligent, but not very highly so; they often place tribute on villages or small towns, demanding maidens for food, or gold. Their number of heads ranges from one to seven or sometimes even more, with three- and seven-headed dragons being most common. The heads also regrow if cut off, unless the neck is "treated" with fire (similar to the hydra in Greek mythology). Dragon blood is so poisonous that Earth itself will refuse to absorb it.

The most famous Polish dragon is the Wawel Dragon or smok wawelski. It supposedly terrorized ancient Kraków and lived in caves on the Vistula river bank below the Wawel castle. According to lore based on the Book of Daniel, it was killed by a boy who offered it a sheepskin filled with sulphur and tar. After devouring it, the dragon became so thirsty that it finally exploded after drinking too much water. A metal sculpture of the Wawel Dragon is a well-known tourist sight in Kraków. It is very stylised but, to the amusement of children, noisily breathes fire every few minutes. The Wawel dragon also features on many items of Kraków tourist merchandise.

Other dragon-like creatures in Polish folklore include the basilisk, living in cellars of Warsaw, and the Snake King from folk legends.

Dragons in Germanic mythology

The most famous dragons in Norse mythology and Germanic mythology, are:

- Níðhöggr who gnawed at the roots of Yggdrasil;

- The dragon encountered by Beowulf;

- Fafnir, who was killed by Siegfried. Fafnir turned into a dragon because of his greed.

- Lindworms are monstrous serpents of Germanic myth and lore, often interchangeable with dragons.

Many European stories of dragons have them guarding a treasure hoard. Both Fafnir and Beowulf's dragon guarded earthen mounds full of ancient treasure. The treasure was cursed and brought ill to those who later possessed it.

Dragons in the emblem books popular from late medieval times through the 17th century often represent the dragon as an emblem of greed. (Some quotes are needed) The prevalence of dragons in European heraldry demonstrates that there is more to the dragon than greed.

Though the Latin is draco, draconis, it has been supposed by some scholars, including John Tanke of the University of Michigan, that the word dragon comes from the Old Norse draugr, which literally means a spirit who guards the burial mound of a king. How this image of a vengeful guardian spirit is related to a fire-breathing serpent is unclear. Many others assume the word dragon comes from the ancient Greek verb derkesthai, meaning "to see", referring to the dragon's legendarily keen eyesight. In any case, the image of a dragon as a serpent-like creature was already standard at least by the 8th century when Beowulf was written down. Although today we associate dragons almost universally with fire, in medieval legend the creatures were often associated with water, guarding springs or living near or under water.

Other European legends about dragons include "Saint George and the Dragon", in which a brave knight defeats a dragon holding a princess captive. This legend may be a Christianized version of the myth of Perseus, or of the mounted Phrygian god Sabazios vanquishing the chthonic serpent, but its origins are obscure.

The tale of George and the Dragon has been modified for modern works, with Saint George portrayed in one Welsh nationalist rendering as an effete wally who faints at the sight of the dragon [5] and a poem by U. A. Fanthorpe based on Paolo Uccello's painting, which hangs in the British National Gallery. In the poem, Saint George is a thug, the Maiden considers the relative sexual merits of the dragon and saint, and the Dragon is the only sane character. Certainly, Uccello's fifteenth-century painting, in which the Maiden has the dragon on a leash, is itself not the most conventional representation of the story.

It is possible that the dragon legends of northwestern Europe are at least partly inspired by earlier stories from the Roman Empire, or from the Sarmatians and related cultures north of the Black Sea. There has also been speculation that dragon mythology might have originated from stories of large land lizards which inhabited Eurasia, or that the sight of giant fossil bones eroding from the earth may have inspired dragon myths (compare Griffin).

The Germanic tribe, the Anglo Saxons, under the warriors Hengest and Horsa broght the symbol of the White Dragon to England in the United Kingdom. Today, the White Dragon is representative of England.

Dragons in Celtic mythology

However, the dragon is now more commonly associated with Wales due to the national flag having a red dragon (Y Ddraig Goch) as its emblem and their national rugby union and rugby league teams are known as the dragons. An ancient story in Britain tells of a white dragon and a red dragon fighting to the death, with the red dragon being the resounding victor. The red dragon is linked with the Britons who are today represented by the Welsh and it is believed that the white dragon refers to the Saxons - now the English - who invaded southern Britain in the 5th and 6th centuries. Some have speculated that it originates from Arthurian Legend where Merlin had a vision of the red dragon (representing Vortigern) and the white dragon (representing the invading Saxons) in battle. That particular legend also features in the Mabinogion in the story of Llud and Llevelys.

It has also been speculated that the red dragon of Wales may have originated in the Sarmatian-influenced Draco standards carried by Late Roman cavalry, who would have been the primary defence against the Saxons. In Cymric language the word "ddraich" means also a chieftain, apparently due to the Roman draco standards.

The Welsh flag is parti per fess Argent and Vert; a dragon Gules passant.

Dragons in Basque mythology

Herensuge is the name given to the dragon in Basque mythology, meaning apparently the "third" or "last serpent". The best known legend has St. Michael descending from Heaven to kill it but only once God accepted to accompany him in person.

Sugaar, the Basque male god, is often associated with the serpent or dragon but able to take other forms as well. His name can be read as "male serpent".

A. Xaho, a romantic myth creator of the 19th century, fused these myths in his own creation of Leherensuge, the first and last serpent, that in his newly coined legend would arise again some time in the future bringing the rebirth of the Basque nation.

Dragons in Catalan mythology

Dragons are well-known in Catalan myths and legends, in no small part because St. George (Catalan Sant Jordi) is the patron saint of Catalonia. Like most dragons, the Catalan dragon (Catalan drac) is basically an enormous serpent with two legs, or, rarely, four, and sometimes a pair of wings. As in many other parts of the world, the dragon's face may be like that of some other animal, such as a lion or bull. As is common elsewhere, Catalan dragons are fire-breathers, and the dragon-fire is all-consuming. Catalan dragons also can emit a fetid odor, which can rot away anything it touches.

The Catalans also distinguish a víbria or vibra (cognate with English viper and wyvern), a female dragon with two prominent breasts, two claws and an eagle's beak.

Dragons in Italian mythology

The legend of Saint George and the dragon is well-known in Italy. But other Saints are depicted fighting a dragon. For instance, the first bishop of the city of Forlì, named Saint Mercurialis, was said to have killed a dragon and saved Forlì. So he often is depicted in the act of killing a dragon. Likewise, the first patron saint of Venice, Saint Theodore of Tyro, was a dragon-slayer, and a statue representing his slaying of the dragon still tops one of the two columns in St. Mark's square.

Dragons in world mythology

The ancient Mesopotamian god Marduk and his dragon, from a Babylonian cylinder seal

- Pergamonmuseum Ishtartor 02.jpg

Oldest known picture of a "dragon" (Ishtar Gate)

Saint George slaying the dragon, as depicted by Paolo Uccello, c. 1470

| Asian dragons | |||

| Chinese dragon | Lung | Lung have a long, scaled serpentine form combined with the attributes of other animals; most (but not all) are wingless, and has four claws on each foot (five for the imperial emblem). They are rulers of the weather and water, and a symbol of power. | |

| Japanese dragon | Ryū | Similar to Chinese and Korean dragons, with three claws instead of four. They are benevolent (with exceptions) and may grant wishes; rare in Japanese mythology. | |

| Vietnamese dragon | Rồng or Long | These dragons' bodies curve lithely, in sine shape, with 12 sections, symbolising 12 months in the year. They are able to change the weather, and are responsible for crops. On the dragon's back are little, uninterrupted, regular fins. The head has a long mane, beard, prominent eyes, crest on nose, but no horns. The jaw is large and opened, with a long, thin tongue; they always keep a châu (gem/jewel) in their mouths (a symbol of humanity, nobility and knowledge). | |

| Korean dragon | Yong | A sky dragon, essentially the same as the Chinese lóng. Like the lóng, yong and the other Korean dragons are associated with water and weather. | |

| yo | A hornless ocean dragon, sometimes equated with a sea serpent. | ||

| kyo | A mountain dragon. | ||

| Siberian dragon | Yilbegan | Related to European Turkic and Slavic dragons | |

| Indian Dragon | Vyalee | Usually seen in temples of South India | |

| European dragons | |||

| Scandinavian & Germanic dragons | lindworm | A very large winged or wingless serpent with two or no legs, the lindworm is really closer to a wyvern. They were believed to eat cattle and symbolized pestilence. On the other hand, seeing one was considered good luck. The dragon Fafnir, killed by the legendary hero Sigurd, was called an ormr ('worm') in Old Norse and was in effect a giant snake; it neither flew nor breathed fire. The dragon killed by the Old English hero Beowulf, on the other hand, did fly and breathe fire. Marco Polo encountered one on his journey. | |

| Welsh dragon | Y Ddraig Goch | The red dragon is the traditional symbol of Wales and appears on the Welsh national flag. | |

| Hungarian dragons (Sárkányok) | zomok | A great snake living in swamp, which regularly kills pigs or sheeps. A group of sheperds can easily kill them. | |

| sárkánykígyó | A giant winged snake, which in fact a full-grown zomok. It often serves as flying mount of the garabonciások (a kind of magicians). The sárkánykígyó rules over storms and bad weather. | ||

| sárkány | A kind of human form dragon. Most of them are giants with multiple heads. Their strength is held in their heads. They become gradually weaker as they lose their heads. | ||

| Slavic dragons | zmey, zmiy, or zmaj | Similar to the conventional European dragon, but multi-headed. They breathe fire and/or leave fiery wakes as they fly. In Slavic and related tradition, dragons symbolize evil. Specific dragons are often given Turkic names (see Zilant, below), symbolizing the long-standing conflict between the Slavs and Turks. | |

| Romanian dragons | balaur | Balaur are very similar to the Slavic zmey: very large, with fins and multiple heads. | |

| Chuvash dragons | Vere Celen | Chuvash dragons represent the pre-Islamic mythology of the same region. | |

| Tatar dragons | Zilant | Really closer to a wyvern, the Zilant is the symbol of Kazan. Zilant itself is a Russian rendering of Tatar yılan, i.e. snake. | |

| Basque dragons | Herensuge | Basque for Dragon. One legend has St. Michael descending from Heaven to kill it, but only when God agreed to accompany him, so fearful it was. | |

| Sugaar | The male god of Basque mythology, also called Maju, was often associated to a serpent or snake, though he can adopt other forms. | ||

| American dragons | |||

| Meso-American dragon | Mex.amphthere or Am.amphithere | Feathered serpent deity responsible for giving knowledge to mankind, and sometimes also a symbol of death and resurrection. | |

| Inca dragon | Amaru | A Dragon(sometimes called a snake) on the Inca Culture. The last Inca emperor Tupak Amaru's name means "Lord Dragon" | |

| Boi-tata | A Dragon-like animal (sometimes like a snake) of the Brazilian indian cultures | ||

| Chilean dragon | Caicaivilu and Tentenvilu | Snake-type dragons, cacaivilu was the sea god and tentenvilu was the earth god, both from the chilean island "Chiloé" | |

| African dragons | |||

| African dragon | Amphisbaena | Possibly originating in northern Africa (and later moving to Greece), this was a two headed dragon (one at the front, and one on the end of its tail). The front head would hold the tail (or neck as the case may be) in its mouth, creating a circle that allowed it to roll. | |

| Dragon-like creatures | |||

| Basilisk | A basilisk is hatched by a cockerel from a serpent's egg. It is a lizard-like or snake-like creature that can supposedly kill by its gaze, its voice, or by touching its victim. Like Medusa, a basilisk may be destroyed by seeing itself in a mirror. | ||

| Leviathan | In Hebrew mythology, a leviathan was a large creature with fierce teeth. Contemporary translations identify the leviathan with the crocodile, but in the Bible, the leviathan can breathe fire (Job 41:18-21), can fly (Job 41:5), and cannot be pierced with spears or harpoons (Job 41:7), his scales so close that there is no room between them (Job 41:15-16), his upright walk (Job 41:12), his teeth close together (Job 41:14), an underbelly that could cut you(Job 41:30) so the identification does not precisely match. Over time, the term came to mean any large sea monster; in modern Hebrew, "leviathan" simply means whale. A sea serpent is also closely related to the dragon, though it is more snakelike and lives in the water. | ||

| Wyvern | Much more similar to a dragon than the other creatures listed here, a wyvern is a winged serpent with either two or no legs. The term wyvern is used in heraldry to distinguish two-legged from four-legged dragons. | ||

| zmeu | Derived from the Slavic dragon, zmeu are humanoid figures that can fly and breathe fire. | ||

Notable dragons

In myth

- Azhi Dahaka was a three-headed demon often characterized as dragon-like in Persian Zoroastrian mythology.

- Similarly, Ugaritic myth describes a seven-headed sea serpent named Lotan.

- The Hydra of Greek mythology is a water serpent with multiple heads with mystic powers. When one was chopped off, two would regrow in its place. This creature was vanquished by Heracles and his cousin.

- Smok Wawelski was a Polish dragon who was supposed to have terrorized the hills around Kraków in the Middle Ages.

- Y Ddraig Goch is now the symbol of Wales (see flag, above), originally appearing as the red dragon from the Mabinogion story Lludd and Llevelys.

- Nidhogg, a dragon in Norse mythology, was said to live in the darkest part of the Underworld, awaiting Ragnarok. At that time he would be released to wreak destruction on the world.

In literature and fiction

The Old English epic Beowulf ends with the hero battling a dragon.

Dragons remain fixtures in fantasy books, though portrayals of their nature differ. For example, Smaug, from The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien, who is a classic, European-type dragon; deeply magical, he hoards treasure and burns innocent towns.

A common theme in literature concerning dragons is the partnership of Dragon Riding between humans and dragons. This is evident in Dragon Rider and the Inheritance Trilogy. Most notably it is featured in Anne McCaffrey's Pern series; however, "dragons" (really genetically modified fire-lizards) feature prominently as workhorses, paired with so-called dragonriders to protect the planet from a deadly threat.

In Ursula K. Le Guin's Earthsea series, the portrayal of dragons undergoes significant changes from book to book.

The dragons in Harry Turtledove's Darkness series, a magical analogue of the Second World War, are beasts, highly pugnacious and under incomplete human control. In the storyline they are the analogue of fighter planes and dragon riders are obviously intended to represent fighter pilots of the Luftwaffe and the RAF.

Dragons have been portrayed in several movies of the past few decades, and in many different forms. In Dragonslayer (1981), a "sword and sorcerer"-type film set in medieval Britain, a dragon terrorizes a town's population. In contrast, Dragonheart (1996), though also given a medieval context, was a much lighter action/adventure movie that spoofed the "terrorizing dragon" stereotype, and depicts dragons as usually good beings, who in fact often save the lives of humans. Dragons can also be passionate protectors, just like the dragoness in Shrek and Shrek 2, who displays her love for a donkey. Reign of Fire (2002), also dark and gritty, dealt with the consequences of dormant dragons reawakened in the modern world.

Dragons are common (especially as non-player characters) in Dungeons & Dragons and in some computer fantasy role-playing games. They, like many other dragons in modern culture, run the full range of good, evil, and everything in between.

On the lighter side, Puff the Magic Dragon was first a poem, later a song made famous by Peter, Paul and Mary, that has become a pop-culture mainstay. The poem tells of an ageless dragon who befriends a young boy, only to be abandoned as the boy ages and dies.

Some stories give accounts of dragons in human form, notably the fourteenth-century French story Voeux du Paon [1] tells the story of Melusine, a beautiful woman who seemed faithful but refused to take communion in church. When confronted, she turned into a dragon and fled. She has been depicted in Russian art of the 18th century as a woman's head on a dragon's body [1].

As emblems

The dragon is the emblem of Ljubljana, Slovenia. The city has a dragon bridge which is embellished with four dragons. The city's basketball club are nicknamed the "Green Dragons". License plates on cars from the city also feature a dragon.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Jones, David (2002). An Instinct for Dragons. Routlege.

- ↑ Rouster, Lourella. (1997). The Footprints of Dragons. http://www.rae.org/dragons.html

- ↑ http://www.abc.net.au/science/k2/moments/s1334145.htm

Further reading

- Dragons, A Natural History by Dr. Karl Shuker Simon & Schuster (1995) ISBN 0-684-81443-9

- The Flight of Dragons by Peter Dickinson HarperCollins (1981) ISBN 0-06-011074-0

- Dragonology: The Complete Book of Dragons by Dugald A. Steer

- A Book of Dragons by Ruth Manning-Sanders (a representative collection of dragon fairy tales from around the world)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

3. Littleton, C. Scott. (2002). Mythology. The Illustrated Anthology of World Myth and Storytelling. London: Duncan Baird.

4. Theosophical University Press. "Encyclopedia Theosophical Glossary Dis – Diz. (1999). Dragons. http://www.theosociety.org/Pasadena.etgloss.dis-diz.htm.

External links

- European Dragons - an illustrated European dragon analysis, citing medieval bestiaries and contemporary works.

- Dragons in Art and on the Web, web directory with 1,470 dragon pictures

- Dragons Across Cultures on draconika.com

- General Dragon Information and Facts

- "Theoi Project" website: Dragons of classical Greece, excerpts from Greek sources, illustrations, lists and links.

- A víbria costume, as worn by a Catalan geganter.

- www.fectio.org.uk - Draco Late Roman military standard

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.