Caduceus

- This article is about the Greek symbol. For the medical symbol often mistakenly referred to as a caduceus, see Rod of Asclepius.

The Caduceus, also known as the wand of Hermes, was a symbol of the Greek god Hermes, who carried a staff (or rod) in his various exploits. This staff was represented by two serpents in the form of a double helix, and sometimes surmounted by wings. In ancient Greece, the two entwined serpents symbolized, among other things, rebirth and regeneration and therefore they were not viewed negatively. The Caduceus was depicted being carried in the left hand of the Greek god Hermes, who was the messenger of the Greek gods, guide of the dead and protector of merchants, gamblers, liars and thieves.

The caduceus is sometimes used as a symbol for medicine, especially in North America, conflating it with the traditional medical symbol, the Rod of Asclepius, which has only a single snake and no wings. Its association with medicine is sometimes traced to Roman mythology, which describes the god Mercury (the Roman version of Hermes) seeing two serpents entwined in mortal combat. Separating them with his wand, Mercury brought about peace between the snakes, and as a result the caduceus came to be seen as a sign of restoration and peace.[1] Correspondingly, in ancient Rome, Livy referred to the caduceator as one who negotiated peace arrangements under the diplomatic protection of the caduceus he carried. The caduceus may also have provided the basis for the astrological symbol representing the planet Mercury.

Etymology and Origin

The Latin word caduceus is an adaptation of the Greek kerukeion, meaning "herald's wand (or staff)," deriving from kerux, meaning "herald" or "public messenger," which in turn is related to kerusso, meaning "to announce" (often in the capacity of herald).[2] Among the Greeks the caduceus is thought to have originally been a herald's staff, which is thought to have developed from a shepherd's crook, in the form of a forked olive branch adorned with first two fillets of wool, then with white ribbons and finally with two snakes intertwined.[3] However no explanation as to how such an object would be practically used as a functional crook by shepherds is offered.

As early as 1910, Dr. William Hayes Ward discovered that symbols similar to the classical caduceus appeared not infrequently on Mesopotamian cylinder seals. He suggested the symbol originated some time between 3000 and 4000 B.C.E., and that it might have been the source of the Greek caduceus.[4] A. L. Frothingham incorporated Dr. Ward's research into his own work, published in 1916, in which he suggested that the prototype of Hermes was an "Oriental deity of Babylonian extraction" represented in his earliest form as a snake god. From this perspective, the caduceus was originally representative of Hermes himself, in his early form as the god Ningishzida, "messenger" of the "Earth Mother".[5] However, more recent classical scholarship makes no mention of Babylonian origin for Hermes or the caduceus.[6]

Mythology

In Greek mythology, several accounts of the origins of the Caduceus are told. One such etiology is found in the story of Tiresias,[7] who found two snakes copulating and killed the female with his staff. Tiresias was immediately turned into a woman, and so remained until he was able to repeat the act with the male snake seven years later. This staff later came in to the possession of the god Hermes, along with its transformative powers. Another myth relates how Hermes played a lyre fashioned from a tortoise shell for Apollo, and in return was appointed ambassador of the gods with the caduceus as a symbol of his office.[8] Another tale suggests that Hermes (or more properly the Roman Mercury) saw two serpents entwined in mortal combat. Separating them with his wand he brought about peace between them, and as a result the wand with two serpents came to be seen as a sign of peace.[9]

In ancient Rome, Livy refers to the caduceator who negotiated peace arrangements under the diplomatic protection of the caduceus he carried.

Symbolism

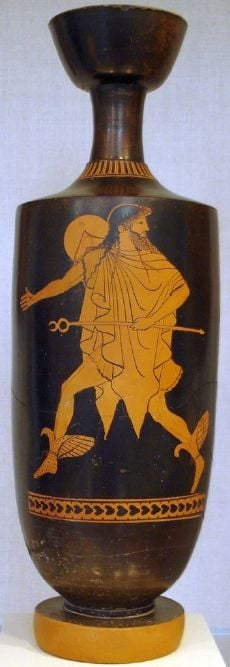

Ancient Greek depictions of the kerukeion are somewhat different from the commonly seen modern representation. Greek vases illustrate the two snakes atop Hermes' staff (or rod), crossed to create a circle with the heads of the snakes resembling horns. This old graphic form, with an additional crossbar to the staff, seems to have provided the basis for the graphical sign of Mercury widely used in works on astronomy, astrology and alchemy.[10] Another simplified variant of the caduceus is to be found in dictionaries, indicating a ‚Äúcommercial term‚ÄĚ entirely in keeping with the association of Hermes with commerce. In this form the staff is often depicted with two winglets attached and the snakes are omitted (or reduced to a small ring in the middle).[11]

Medicine

The caduceus symbol is sometimes used as a symbol for medicine or doctors (instead of the Rod of Asclepius) even though the symbol has no connection with Hippocrates and any association with healing arts is something of a stretch;[12] its singularly inappropriate connotations of theft, deception and death have provided fodder for academic humor:[13]

"As god of the high-road and the market-place Hermes was perhaps above all else the patron of commerce and the fat purse: as a corollary, he was the special protector of the traveling salesman. As spokesman for the gods, he not only brought peace on earth (occasionally even the peace of death), but his silver-tongued eloquence could always make the worse appear the better cause. From this latter point of view, would not his symbol be suitable for certain Congressmen, all medical quacks, book agents and purveyors of vacuum cleaners, rather than for the straight-thinking, straight-speaking therapist? As conductor of the dead to their subterranean abode, his emblem would seem more appropriate on a hearse than on a physician's car."[14]

However, attempts have been made to argue that the caduceus is appropriate as a symbol of medicine or of medical practitioners. Apologists have suggested that the sign is appropriate for military medical personnel because of the connotations of neutrality. Some have pointed to the putative origins of the caduceus in Babylonian mythology (as described above), particularly the suggested association with Ishtar as "an awakener of life and vegetation in the spring" as justification for its association with healing, medicine, fertility and potency.[15]

A 1992 survey of American health organizations found that 62 percent of professional associations used the rod of Asclepius, whereas in commercial organizations, 76 percent used the caduceus.[16]

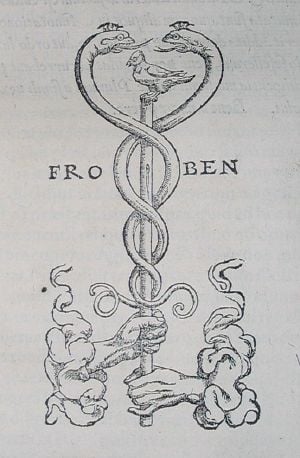

The first known use of the caduceus in a medical context was in the printer's vignette used by the Swiss medical printer Johann Frobenius (1460-1527), who used the staff entwined with serpents, not winged but surmounted by a dove, with the biblical epigraph "Be ye therefore wise as serpents and harmless as doves"[17] The caduceus was also apparently used as a symbol by Sir William Butts, physician to Henry VIII.[18] A silver caduceus presented to Caius College, Cambridge by John Caius and carried before him on the cushion he supplied in official visits to the college remains in the College's possession.[19]

However, widespread confusion regarding the supposed medical significance of the caduceus appears to have arisen as a result of events in the United States in the nineteenth century.[20] It had appeared on the chevrons of Army hospital stewards as early as 1856.[21] In 1902, it was added to the uniforms of U.S. Army medical officers. This was brought about by one Captain Reynolds,[22] who after having the idea rejected several times by the Surgeon General, persuaded the new incumbent‚ÄĒBrig. Gen. William H. Forwood‚ÄĒto adopt it. The inconsistency was noticed several years later by the librarian to the Surgeon General, but the symbol was not changed.[20] In 1901, the French periodical of military medicine was named La Caduc√©e. The caduceus was formally adopted by the Medical Department of the United States Army in 1902.[20] After World War I, the caduceus was employed as an emblem by both the Army Medical Department and the Navy Hospital Corps. Even the American Medical Association used the symbol for a time, but in 1912, after considerable discussion, the caduceus was abandoned and the rod of Asclepius was adopted instead.

There was further confusion caused by the use of the caduceus as a printer's mark (as Hermes was the god of eloquence and messengers), which appeared in many medical textbooks as a printing mark, although subsequently mistaken for a medical symbol.[20]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Stuart L. Tyson, "The Caduceus," The Scientific Monthly 34 (6): 495

- ‚ÜĎ Liddell and Scott, Greek-English Lexicon; Stuart L. Tyson, The Caduceus, in The Scientific Monthly 34 (6): 493

- ‚ÜĎ Richard Lewis Farnell. Cults of The Greek States, Vol. V. reprint ed. Kessinger Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1417921633), 20, cited in Tyson, 494

- ‚ÜĎ William Hayes Ward. The Seal Cylinders of Western Asia. (Washington: Carnegie Institute of Washington, 1910) [1]books.google. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ A. L. Frothingham, "Babylonian Origins of Hermes the Snake-God, and of the Caduceus," in American Journal of Archaeology 20 (2): 175-211

- ‚ÜĎ For example, the Oxford Classical Dictionary, Third Ed., edited by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth, (Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 019866172X) in the article on Hermes, makes no mention of any Mesopotamian origin and refers to the caduceus as having originally been a herald's staff, entirely in keeping with the etymology of the word.

- ‚ÜĎ Keith Blayney, September 2002, The Caduceus vs the Staff of Asclepius. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Tyson, 494

- ‚ÜĎ Tyson, 495

- ‚ÜĎ Signs and Symbols Used In Writing and Printing, p 269, in Webster's New Twentieth Century Dictionary of the English Language, unabridged, New York, 1953. Here the symbol of the planet Mercury is indicated as "the caduceus of Mercury, or his head and winged cap".

- ‚ÜĎ For example, see the Unicode standard, where the "staff of Hermes" signifies "a commercial term or commerce".

- ‚ÜĎ Bernice S. Engle, "The Use of Mercury's Caduceus as a Medical Emblem," The Classical Journal 25(3) (December 1929):204-208).

- ‚ÜĎ Tyson, 492-498

- ‚ÜĎ Tyson, 495

- ‚ÜĎ Engle, 204-208

- ‚ÜĎ Walter J. Friedlander. The Golden Wand of Medicine: A History of the Caduceus symbol in medicine. (Boulder, CO: Greenwood Press, 1992)

- ‚ÜĎ Matthew 10:16¬†; Engle, 204

- ‚ÜĎ Engle, 204

- ‚ÜĎ Engle, 204f.

- ‚ÜĎ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Robert A. Wilcox and Emma M. Whitham, The symbol of modern medicine: why one snake is more than two. 15 April 2003, Annals of Internal Medicine. accessdate 2007-06-15

- ‚ÜĎ Lt.-Col. Fielding H. Garrison, "The use of the caduceus in the insignia of the Army medical officer," Bulletin of the Medical Library Association 9 (1919-1920): 13-16, noted by Engle, 204, note 2.

- ‚ÜĎ Engle, 207 states, however, "The use of the caduceus in our army I believe to be due chiefly to the late Colonel Hoff, who has emphasized the suitability of the caduceus as an emblem of neutrality."

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burkert, Walter. Structure and History in Greek Mythology and Ritual. Translation, University of California, 1982. ISBN 0520047702.

- Engle, Bernice S. "The Use of Mercury's Caduceus as a Medical Emblem," The Classical Journal 25(3) (December 1929): 204-208.

- Farnell, Cults of The Greek States, Vol. V. 20, cited in Stuart L. Tyson, The Caduceus, in The Scientific Monthly 34 (6): 494.

- Friedlander, Walter J. The Golden Wand of Medicine: A History of the Caduceus symbol in medicine. Boulder, CO: Greenwood Press, 1992. ISBN 0313280231. OCLC 24246627.

- Frothingham, A. L. "Babylonian Origins of Hermes the Snake-God, and of the Caduceus," in American Journal of Archaeology 20 (2): 175-211.

- Oxford Classical Dictionary, Third Ed., edited by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth, Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 019866172X.

- Wilcox, Robert A., and Emma M. Whitham, "The symbol of modern medicine: why one snake is more than two." Annals of Internal Medicine (2003).

External links

All links retrieved November 25, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.