Difference between revisions of "Bison" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 197: | Line 197: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | * Intertribal Bison Cooperative (IBC). 2006. Website[http://www.intertribalbison.org] | |

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* Lott, D.F. 2002. ''American Bison''. Berkeley, California, USA : University of California Press | * Lott, D.F. 2002. ''American Bison''. Berkeley, California, USA : University of California Press | ||

| + | * National Bison Association (NBA). 2006 Website[http://www.bisoncentral.com] | ||

* Nowak, R.M. and Paradiso, J.L. 1983. ''Walker's Mammals of the World''. Baltimore, Maryland, USA : The Johns Hopkins University Press | * Nowak, R.M. and Paradiso, J.L. 1983. ''Walker's Mammals of the World''. Baltimore, Maryland, USA : The Johns Hopkins University Press | ||

* Voelker, W. 1986. ''The Natural History of Living Mammals''. Medford, New Jersey, USA : Plexus Publishing, Inc. | * Voelker, W. 1986. ''The Natural History of Living Mammals''. Medford, New Jersey, USA : Plexus Publishing, Inc. | ||

Revision as of 19:12, 11 November 2006

| Bison | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wisent European Bison | ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Species | ||||||||||||||

|

B. antiquus |

Bison are members of the genus Bison of the Bovid family of the even-toed ungulates, or hoofed mammals. There are three types of living bison:

- The American bison (Bison bison bison), the most famous bison, formerly one of the most common large animals in North America

- The Wood bison (Bison bison athabascae), considered to be a subspecies of the American bison

- The European bison or Wisent (Bison bonasus)

There were also several other species of bison which became extinct within the last 10,000 years.

Bison are very closely related to cattle, yaks, true buffalo, and other members of the subfamily Bovinae.

American Bison

| American Bison Conservation status: Lower risk | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Alternate image | ||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||||

| Bison bison Linnaeus, 1758 | ||||||||||||||||

| Subspecies | ||||||||||||||||

|

B. b. athabasacae |

The American Bison (Bison bison) is a bovine mammal that is the largest terrestrial mammal in North America, and one of the largest wild cattle in the world. With their huge bulk, wood bison – which are the largest subspecies in North America – are only surpassed in size by the massive Asian gaur and wild water buffalo, both of which are found mainly in India. The bison inhabited the Great Plains of the United States and Canada in massive herds, ranging from the Great Slave Lake in Canada's far north to Mexico in the south, and from eastern Oregon almost to the Atlantic Ocean, taking its subspecies into account. Its two subspecies are the Plains Bison (Bison bison bison), distinguished by its smaller size and more rounded hump, and the Wood Bison (Bison bison athabascae), distinguished by its larger size and taller square hump.

The Bison is also commonly known as the American Buffalo, although it is only distantly related to either the Water Buffalo or African Buffalo.

Physiology

Bison have a shaggy, dark brown winter coat, and a lighter weight, lighter brown summer coat. Bison can reach up to 2 meters (6½ ft) tall, 3 meters (10 ft) long and weigh 450 to 900 kilograms (900 to 2,000 lb). The biggest specimens on record have weighed as much as 1140 kg (2,500 lb). The heads and forequarters are massive, and both sexes have short, curved horns, which they use in fighting for status within the herd and for defense. Bison mate in August and September; a single reddish-brown calf is born the following spring, and it nurses for a year. Bison are mature at three years of age, and have a life expectancy of 18 to 22 years in the wild and 35 to 40 years in captivity.

One very rare condition results in the white buffalo, where the calf turns entirely white. It is not to be confused with albino, since white bison still possess pigment in the skin, hair, and eyes. White bison are considered sacred by many Native Americans.

Due to its size and the protection afforded by living in a herd, the bison has few enemies besides humans. Grizzly bears and packs of wolves may attempt to attack a young calf or subadult, but only in the dead of winter when the herd cannot expend the energy to protect stragglers. A wolf pack can also take down an adult bison. The only threat, other than hunting by humans, that leads to the depletion of wild bison is interbreeding with domestic bovines. In fact, only a small number of bison herds found in North America today are pure breed bisons.

Reproductive habits and sexual behavior

Their mating habits are polygynous: dominant bulls maintain a small harem of females for mating. Individual bulls "tend" females until allowed to mate, following them around and chasing away rival males.

Juveniles are lighter in color than mature bison for the first three months of their life. The mating season is in middle to late summer, as late as September in northern ranges. Gestation is 285 days in length, and so the calves are typically born in the spring. [1]

Native hunting

The American Bison is a relative newcomer to North America, having originated in Eurasia and migrated over the Bering Strait. About 10,000 years ago it replaced the Long-horned Bison (Bison priscus), a previous immigrant that was much larger. It is thought that the Long-horned Bison may have gone extinct because of a changing ecosystem and hunting pressure following the development of the Clovis point and related technology, and improved hunting skills. During this same period, other megafauna vanished and were replaced to some degree by immigrant Eurasian animals that were better adapted to predatory humans. The American bison, technically a dwarf form, was one of these animals. Another was the brown bear, which replaced the short-faced bear.

Bison were a keystone species, whose grazing pressure was a force that shaped the ecology of the Great Plains as strongly as periodic prairie fires and which were central to the lifestyle of Native Americans of the Great Plains. But there is now some controversy over their interaction. "Hernando De Soto's expedition staggered through the Southeast for four years in the early 16th century and saw hordes of people but apparently did not see a single bison," Charles C. Mann writes in 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Mann discusses the evidence that Native Americans not only created (by selective use of fire) the large grasslands that provided the bison's ideal habitat but also kept the bison population regulated. In this theory, it was only when the aboriginal population was decimated by wave after wave of epidemic (from diseases of Europeans) after the 16th century that the bison herds propagated wildly. In such a view, the seas of bison herds that stretched to the horizon were a symptom of an ecology out of balance, only rendered possible by decades of heavier-than-average rainfall. Bison were the most numerous single species of large wild mammal on Earth.

What is not disputed is that before the introduction of horses, bison were herded into large chutes made of rocks and willow branches and then stampeded over cliffs. These bison jumps are found in several places in the U.S. and Canada, such as Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. Large groups of people would herd the bison for several miles, forcing them into a stampede that would ultimately drive many animals over a cliff. The large quantities of meat obtained in this way provided the hunters with surplus which they could trade with other cultures. A similar method of hunting was to drive the bison into natural corrals, such as Ruby site.

To get full use out of the bison, the Native Americans had a specific method of butchery, first identified at the Olsen-Chubbock archeological site in Colorado. The method involves skinning down the back in order to get at the tender meat just beneath the surface, the area known as the "hatched area." After the removal of the hatched area, the front legs are cut off as well as the shoulder blades. Doing so exposes the hump meat (in the Wood Bison), as well as the meat of the ribs and the Bison's inner organs. After everything was exposed, the spine was then severed and the pelvis and hind legs removed. Finally, the neck and head were removed as one. This allowed for the tough meat to be dried and made into pemmican.

Later when Plains Indians obtained horses, it was found that a good horseman could easily lance or shoot enough bison to keep his tribe and family fed, as long as a herd was nearby. The bison provided meat, leather, sinew for bows, grease, dried dung for fires, and even the hooves could be boiled for glue. When times were bad, bison were consumed down to the last bit of marrow.

Buffalo trails

The first thoroughfares of North America, save for the time-obliterated paths of mastodon or musk-ox and the routes of the Mound Builders, were the traces made by bison and deer in seasonal migration and between feeding grounds and salt licks. Many of these routes, hammered by countless hoofs instinctively following watersheds and the crests of ridges in avoidance of lower places' summer muck and winter snowdrifts, were followed by the Indians as courses to hunting grounds and as warriors' paths; they were invaluable to explorers and were adopted by pioneers. Bison traces were characteristically north and south; there were, however, several key east-west trails which were used later as railways. Some of these include the Cumberland Gap; along the New York watershed; from the Potomac River through the Allegheny divide to the Ohio River headwaters; and through the Blue Ridge Mountains to upper Kentucky. In Senator Thomas Hart Benton's phrase saluting these sagacious pathmakers, the buffalo blazed the way for the railroads to the Pacific.

Source: James Truslow Adams, 1940. Dictionary of American History (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons)

Buffalo hunts

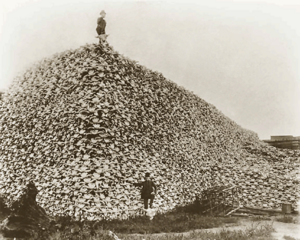

Bison were hunted almost to extinction in the 19th century and were reduced to a few hundred head by the mid-1880s, from which all the present day's managed herds are descended. One major cause was that hunters were paid by large railroad concerns to destroy entire herds, for several reasons:

- The herds formed the basis of the economies of local Plains tribes of Native Americans; without bison, the tribes would leave.

- Herds of these large animals on tracks could damage locomotives when the trains failed to stop in time.

- Herds often took shelter in the artificial cuts formed by the grade of the track winding though hills and mountains in harsh winter conditions. As a result, the herds could delay a train for days.

Bison skins were used for industrial machine belts, clothing such as robes, and rugs. There was a huge export trade to Europe of bison hides. Old West bison hunting was very often a big commercial enterprise, involving organized teams of one or two professional hunters, backed by a team of skinners, gun cleaners, cartridge reloaders, cooks, wranglers, blacksmiths, security guards, teamsters, and numerous horses and wagons. Men were even employed to recover and re-cast lead bullets taken from the carcasses. Many of these professional hunters such as Buffalo Bill Cody killed over a hundred animals at a single stand and many thousands in their career. One professional hunter killed over 20,000 by his own count. A good hide could bring $3.00 in Dodge City, Kansas, and a very good one (the heavy winter coat) could sell for $50.00 in an era when a laborer would be lucky to make a dollar a day.

The hunter would customarily locate the herd in the early morning, and station himself about 100 meters from it, shooting the animals broadside through the lungs. Head shots were not preferred as the soft lead bullets would often flatten and fail to penetrate the skull, especially if mud was matted on the head of the animal. The bison would drop until either the herd sensed danger and stampeded or perhaps a wounded animal attacked another, causing the herd to disperse. If done properly a large number of bison would be felled at one time. Following up were the skinners, who would drive a spike through the nose of each dead animal with a sledgehammer, hook up a horse team, and pull the hide from the carcass. The hides were dressed, prepared, and stacked on the wagons by other members of the organization.

For a decade from 1873 on there were several hundred, perhaps over a thousand, such commercial hide hunting outfits harvesting bison at any one time, vastly exceeding the take by American Indians or individual meat hunters. The commercial take arguably was anywhere from 2000 to 100,000 animals per day depending on the season, though there are no statistics available. It was said that the Big .50s were fired so much that hunters needed at least two rifles to let the barrels cool off; The Fireside Book of Guns reports they were sometimes quenched in the winter snow. Dodge City saw railroad cars sent East filled with stacked hides.

As the great herds began to wane, proposals to protect the bison were discussed. Cody, among others, spoke in favor of protecting the bison because he saw that the pressure on the species was too great. But these were discouraged since it was recognized that the Plains Indians, often at war with the United States, depended on bison for their way of life. General Phillip Sheridan spoke to the Texas Legislature against a proposal to outlaw commercial bison hunting for that reason, and President Grant also "pocket vetoed" a similar Federal bill to protect the dwindling bison herds. By 1884, the American Bison was close to extinction.

Comeback

The Famous Buffalo Herd of James "Scotty" Philip in South Dakota was the beginning of the reintroduction of Bison to North America. In 1899, he purchased a small herd (5 of them, including the female) from Dug Carlin, Pete Dupree's brother-in-law, whose son Fred had roped 5 calves in the Last Big Buffalo Hunt on the Grand River in 1881 and taken them back home to the ranch on the Cheyenne River. At the time of purchase there were approximately 7 pure buffalo and it was believed to be one of the largest known herds left in North America. Scotty's goal was to preserve the animal from extinction. At the time of his death in 1911 at 53, Scotty had grown the herd to an estimated 1,000 to 1,200 head of Bison.

A variety of privately owned herds have also been established, starting from this population. The current American Bison population has been growing rapidly and is estimated at 350,000, but this is compared to an estimated 60–100 million in the mid-19th century. Current herds, however, are all partly crossbred with cattle (see "beefalo"); today there are only four genetically unmixed herds and only one that is also free of brucellosis: it roams Wind Cave National Park. A founder population from the Wind Cave herd was recently established in Montana by the World Wildlife Fund.

The only continuously wild bison herd in the United States resides within Yellowstone National Park. Numbering between 3000 and 3500, this herd is descended from a remnant population of 23 individual mountain bison that survived the mass slaughter of the 1800s by hiding out in the Pelican Valley of Yellowstone Park. In 1902, a captive herd of 21 plains bison were introduced to the Lamar Valley and managed as livestock until the 1960s, when a policy of natural regulation was adopted by the park.

The end of the ranching era and the onset of the natural regulation era set into motion a chain of events that have led to the bison of Yellowstone Park migrating to lower elevations outside the park in search of winter forage. The presence of wild bison in Montana is perceived as a threat to many cattle ranchers, who fear that the small percentage of bison that carry brucellosis will infect livestock and cause cows to abort their first calves. However, there has never been a documented case of brucellosis being transmitted to cattle from wild bison. The management controversy that began in the early 1980s continues to this day, with advocacy groups arguing that the Yellowstone herd should be protected as a distinct population segment under the Endangered Species Act.

Bison hunting today

Hunting of wild bison is legal in some states and provinces where public herds require culling to maintain a target population. In Alberta, where one of only two continuously wild herds of bison exist in North America at Wood Buffalo National Park, bison are hunted to protect disease free herds of public (reintroduced) and private herds of bison. In Montana a public hunt was re-established in 2005, with 50 permits being issued. The Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks Commission increased the number of tags to 140 for the 2006/2007 season. Advocacy groups claim that it is premature to re-establish the hunt, given the bison's lack of habitat and wildlife status in Montana.

One of the bison's few natural predators is the wolf. Wolves will usually prey on the females and young and rarely will go for healthy bulls. Bears will also prey on the young of bison.

American Bison today

Bison are now raised for meat and hides. Over 250,000 of the 350,000 remaining bison are being raised for human consumption. Bison meat is lower in fat and cholesterol than beef which has led to the development of beefalo, a fertile cross-breed of bison and domestic cattle. In 2005, about 35,000 bison were processed for meat in the U.S., with the National Bison Association and USDA providing a "Certified American Buffalo" program with birth-to-consumer tracking of bison via RFID ear tags.

Recent genetic studies of privately owned herds of bison show that many of them include animals with genes from domestic cattle; there are as few as 12,000 to 15,000 pure bison in the world. The numbers are uncertain because the tests so far used mitochondrial DNA analysis, and thus would miss cattle genes inherited in the male line; most of the hybrids look exactly like purebred bison.

The American Bison was depicted on the reverse side of the U.S. "buffalo nickel" from 1913 to 1938. In 2005, the United States Mint coined a nickel with a new depiction of the bison as part of its "Westward Journey" series; the Kansas and North Dakota quarters have a depiction of the bison on its reverse as part of its "50 State Quarter" series. The Kansas State Quarter only has the bison and does not feature any writing. The North Dakota State Quarter has two bison.

The bison is a symbol of Manitoba, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Bucknell University, the University of Colorado, Lipscomb University, Harding University, Marshall University, the Independence Party of Minnesota, and North Dakota State University. It is also commonly used as a symbol of the city of Buffalo, New York and its professional sports teams, the Buffalo Bills and Buffalo Sabres, although the city was not named for the animal. The bison is also the state mammal of Wyoming. It is the state animal of Kansas (see Governor of Kansas Quick Facts).

Custer State Park in South Dakota is home to 1,500 bison, one of the largest publicly held herds in the world.

A proposal known as Buffalo Commons has been suggested by a handful of academics and policymakers to restore large parts of the drier portion of the Great Plains to native prairie grazed by bison. Proponents argue that current agricultural use of the shortgrass prairie is not sustainable, pointing to periodic disasters such as the Dust Bowl and continuing significant population loss over the last 60 years. However, this plan is opposed by most who live in the sparsely-populated area, though it might benefit participating states economically.

Dangers

Bison are among the most dangerous animals encountered by visitors to the various U.S. National Parks, especially Yellowstone National Park. Although they are not carnivorous, they will attack humans if provoked. They appear slow because of their lethargic movements, but they can easily outrun humans—they have been observed running as fast as 35 miles per hour. Between 1978 and 1992, over four times as many people in Yellowstone National Park were killed or injured by bison as by bears (12 by bears, 56 by bison). Bison also have the unexpected ability, given the animal's size and body structure, to leap over a standard barbed-wire fence.

Native American names for bison

Though commonly called buffalo or bison in English, Native American languages also have many names for the animal. They include:

- Tatanka (Lakota)

- Yąnąsh (Choctaw)

Wisent

The Wisent or European Bison (Bison bonasus) (IPA: [ˈviːzənt]) is a bison species and the heaviest land animal in Europe. A typical wisent is about 2.9 m long and 1.8–2 m tall, and weighs 300 to 1000 kg. It is typically lankier and less massive than the related American bison (B. bison), and has shorter hair on the neck, head, and forequarters. Wisents are forest-dwelling. They have few predators with only scattered reports from the 1800s of wolf and bear predation. Wisents were first scientifically described by Carolus Linnaeus in 1758. Some later descriptions treat the wisent as conspecific with the American bison. It is not to be confused with the aurochs.

The species is now endangered. In the past they were commonly killed to produce hides and drinking horns especially in the middle ages.

Near-extinction

In Western Europe, wisent were extinct by the 11th century except in the Ardennes, where they lasted into the 14th century. The last wisent in Transylvania died in 1790.

In the east, wisent were legally the property of the Polish kings, Lithuanian princes and Russian Tsars. King Sigismund the Old of Poland instituted the death penalty for poaching a wisent in the mid-1500s. Despite these and other measures, the wisent population continued to decline over the following four centuries. The last wild wisent in Poland was killed in 1919 and the last wild wisent in the world was killed by poachers 1927 in the Western Caucasus. By that year fewer than 50 remained, all in zoos.

Wisents were re-introduced successfully into the wild beginning in 1951. They are found living free-ranging in forest preserves like Western Caucasus in Russia and Białowieża Forest in Poland and Belarus. Free-ranging herds are found in Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Romania, Russia and Kyrgyzstan. Zoos in 30 countries also have quite a few animals. There were 3000 individuals as of 2000, all descended from only 12 individuals. Because of their limited genetic pool, they are considered highly vulnerable to diseases like foot and mouth disease.

Wisents are now found in the 30km exclusion zone around Chernobyl. As with other animals, it seems that the benefits of removing people from the zone have far outweighed any harm from radiation. [2]

In 1996 the IUCN classified the wisent as endangered.

More details

Wisent have lived as long as 28 years in captivity although in the wild their lifespan is shorter. Productive breeding years are between 4 and 20 years old in females and only between 6 and 12 years old in males. Wisent occupy home ranges of as much as 100 square kilometers and some herds are found to prefer meadows and open areas in forests.

Wisent can cross-breed with American Bison. The products of a German interbreeding program were destroyed after World War II. This program was related to the impulse which created the Heck cattle. The cross-bred individuals created at other zoos were eliminated from breed books by the 1950s. A Russian back-breeding program resulted in a wild herd of hybrid animals which presently lives in the Caucasian Biosphere Reserve (550 individuals in 1999).

There are also bison-wisent-cattle hybrids. In 1847 a herd of wisent-cattle hybrids named żubroń was created by Leopold Walicki. The animal was to become a durable and cheap alternative to cattle. The experiment was continued by researchers from the Polish Academy of Sciences until the late 1980s. Although the program resulted in a quite successful animal that was both hardy and could be bred in marginal grazing lands, it was eventually discontinued. Currently the only surviving żubroń herd consists of just a few animals in Białowieża Forest, Poland.

Three sub-species have been identified:

- Lowland wisent - Bison bonasus bonasus (Linneus, 1758) – (from Białowieża Forest)

- Hungarian (Carpathian) wisent - Bison bonasus hungarorum - extinct

- Caucasus wisent - Bison bonasus caucasicus - extinct, although one individual, a bull named Kaukasus was one of the 12 founders of the modern herds

The modern herds are managed as two separate lines - one consisting of only Bison bonasus bonasus (all descended from only 7 animals) and one consisting of all 12 ancestors including the one Bison bonasus caucasicus bull. Only a limited amount of inbreeding depression from the population bottleneck has been found, having a small effect on skeletal growth in cows and a small rise in calf mortality. Genetic variability continues to shrink. From 5 initial bulls, all current wisent bulls have one of only two remaining Y chromosomes.

Trivia

- The wisent (or Zubr in Slavic languages) is the largest wild animal in Belarus, and it is a national symbol of Belarus today.

- A wisent head (sometimes identified with an aurochs) featured on Moldavia's state symbols, a depiction connected with the legend of the country's foundation.

- Żubrówka Polish vodka is indirectly named after this animal (żubr in Polish). Each bottle contains a stalk of "bison grass", which produces a slighly yellowish colour and a distinctive flavour.

See also

- Żubroń

- List of extinct animals of Europe

- Carpathian Wisent

- Caucasian Wisent

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Intertribal Bison Cooperative (IBC). 2006. Website[1]

- Lott, D.F. 2002. American Bison. Berkeley, California, USA : University of California Press

- National Bison Association (NBA). 2006 Website[2]

- Nowak, R.M. and Paradiso, J.L. 1983. Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore, Maryland, USA : The Johns Hopkins University Press

- Voelker, W. 1986. The Natural History of Living Mammals. Medford, New Jersey, USA : Plexus Publishing, Inc.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ The Gale Group, Inc. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia artice on American bison. Accessed Aug 13th 2006

- ↑ Wildlife defies Chernobyl radiation, by Stefen Mulvey, BBC News