Anti-Semitism

Anti-Semitism (alternatively spelled antisemitism) is hostility toward or prejudice against Jews as a religious, ethnic, or racial group, which can range from individual hatred to institutionalized, violent persecution. The highly explicit ideology of Adolf Hitler's Nazism was the most extreme example of this phenomenon, leading to a genocide of the European Jewry.

Anti-Semitism takes several different forms:

- Religious anti-Semitism, or anti-Judaism. Before the 19th century, most anti-Semitism was primarily religious in nature, based on Christian or Islamic interactions with and interpretations of Judaism. Since Judaism was generally the largest minority religion in Christian Europe and much of the Islamic world, Jews were often the primary targets of religiously-motivated violence and persecution from Christian and, to a lesser degree, Islamic rulers. Unlike anti-Semitism in general, this form of prejudice is directed at the religion itself, and so generally does not affect those of Jewish ancestry who have converted to another religion, although the case of Conversos in Spain was a notable exception.

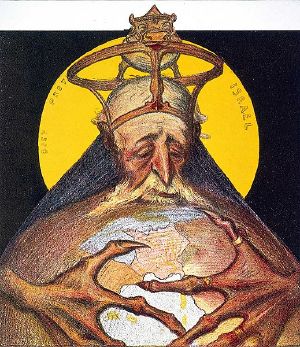

- Racial anti-Semitism. With its origins in the anthropological ideas of race that started during the Enlightenment, racial anti-Semitism became the dominant form of anti-Semitism from the late 19th century through today. Racial anti-Semitism replaced the hatred of Judaism as a religion with the idea that the Jews themselves were a racially distinct group, regardless of their religious practice, and that they were inferior or worthy of animosity. With the rise of racial anti-Semitism, conspiracy theories about Jewish plots in which Jews were acting in concert to dominate the world became a popular form of anti-Semitic expression.

- New anti-Semitism. Many analysts and Jewish groups believe there is a distinctly new form of late 20th century anti-Semitism, called the New anti-Semitism, which is associated with the Left, rather than the /right, borrowing language and concepts from anti-Zionism.[1] [2]

Etymology and usage

Technically, "anti-semitism" refers not only to Jews but all semitic peoples, including the Arabs. However, historically, it refers to prejudice towards Jews alone, and this was the only use of this word for more than a century.

German political agitator Wilhelm Marr coined the German word Antisemitismus in his book "The Way to Victory of Germanicism over Judaism" in 1879. Marr used the term as a pseudo-scientific synonym for Jew-hatred or Judenhass. Marr's book became very popular, and in the same year he founded the "League of Anti-Semites" ("Antisemiten-Liga"), the first German organization committed specifically to combatting the alleged threat to Germany posed by the Jews and advocating their forced removal from the country.

In recent decades some groups have argued that the term should be extended to include prejudice against Arabs, otherwise known as Anti-Arabism. However, Bernard Lewis, Professor of Near Eastern Studies Emeritus at Princeton University, points out that until now, "Anti-Semitism has never anywhere been concerned with anyone but Jews."[3]

Early anti-Semitism

The earliest occurrence of anti-Semitism has been the subject of debate among scholars. The basis for the prejudice against Jews revolved around their insistence that their deity alone was the True God, their refusal to eat food considered normal, and their keeping separate from the gentile neighbors. The Book of Esther, usually throught to have been written in the third or fourth century B.C.E., deals with anti-semitism in the Persian Empire, personified by the villain Haman. Although this may or may not have been historical, it does provide evidence that Jews at the time of Esther's writing considered anti-semitism a threat. Egyptian prejudices against Jews are evidenced in the writings of the Egyptian priest Manetho in the third century B.C.E.[4] These views seem to have been widespread in the Greek Empire, where Jews faced hostility in the Diaspora. Jews sometimes violently resisted Greek attempts to force them to do obeisence to Greek emperors such as Antiochus Epiphanes, gaining them a reputation as arrogant and disloyal to imperial authority. This reputation carried over into Roman times. The Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria in his Flaccus, described an attack on Jews in Alexandria in 38 C.E., in which thousands of Jews died. Philo describes Flaccus, the Roman governor of the city, as allowing Greek mobs to erect statues of their deities in Jewish synagogues and then declaring the Jews outlaws when they resisted.[5]

Anti-Judaism in the New Testament

The animosity between Christians and Jews began as argument between Jews who accepted Jesus as the Messiah and other Jews who denied his Messiahship. The early Jewish followers of Jesus continued to practice circumcision and observe the Jewish dietary laws (Acts 11:3; 15:1ff; 16:3). But this intra-Jewish debate over the Jewish Jesus soon dove-tailed with Roman anti-Judaism and created a tradition of Christian anti-semitism that lasted for two mellennia.

Most of the New Testament was written by Jews who became followers of Jesus. However, because of the increasingly bitter feelings between traditional Jews and the communities that accepted Jesus as the Messiah, a number of passages in the New Testament display harsh attitudes toward "the Jews." Such passages have frequently been used for anti-Semitic purposes, for example:

- Jesus speaking to a group of Pharisees: "I know that you are descendants of Abraham; yet you seek to kill me, because my word finds no place in you. I speak of what I have seen with my Father, and you do what you have heard from your father. They answered him, "Abraham is our father." Jesus said to them, "If you were Abraham's children, you would do what Abraham did. ... You are of your father the devil, and your will is to do your father's desires... If I tell the truth, why do you not believe me? He who is of God hears the words of God; the reason why you do not hear them is you are not of God." (John 8:37-39, 44-47, RSV)

- Stephen speaking before a synagogue council just before his execution: "You stiff-necked people, uncircumcised in heart and ears, you always resist the Holy Spirit. As your fathers did, so do you. Which of the prophets did not your fathers persecute? And they killed those who announced beforehand the coming of the Righteous One, whom you have now betrayed and murdered, you who received the law as delivered by angels and did not keep it." (Acts 7:51-53, RSV)

Some biblical scholars hold that verses like these reflect the Jewish-Christian tensions that were emerging in the late first or early second century, and do not originate with Jesus. Others point out that Jesus and Stephen are presented as Jews speaking to other Jews, and that their use of broad accusation against Israel is borrowed from Moses and the later Jewish prophets (e.g. Deut 9:13-14; 31:27-29; 32:5, 20-21; 2 Kings 17:13-14; Is 1:4; Hos 1:9; 10:9). In any case, Chrstians soon stopped thinking of themselves in any sense as Jews, and the passages indicting those Jews who rejected Jesus were viewed as pertaining to the Jews collectively.

Christian Anti-Semitism in the Roman Empire

A number of early and influential Church works display strongly anti-Jewish attitdues. After the Jewish revolt of 70 C.E. the Jews become "wholly other" to Christians. Christians often took the attitude that the suffering of the Jews was justified because the Jews had rejected of Jesus. The apocryphal Letter of Barnabas declares that Jesus had abolished the Jewish Law and portrays the Jews as worldly and materialistic, accusing them of being "wretched men [who] set their hope on the building (the Temple), and not on their God that made them." In his Dialogue with Trypho the Jew, the Christian apologist Justin Martyr said:

- The circumcision according to the flesh, which is from Abraham, was given for a sign; that you may be separated from other nations, and from us; and that you alone may suffer that which you now justly suffer; and that your land may be desolate, and your cities burned with fire; and that strangers may eat your fruit in your presence, and not one of you may go up to Jerusalem... These things have happened to you in fairness and justice, for you have slain the Just One, and His prophets before Him.' (Dialogue with Trypho, ch. 16)

In the second century, some Christians went so far as to declare that the God of the Jews was a a different being altogether from the loving Heavenly Father described by Jesus. The popular preacher Marcion developed a strong following for this belief, even arguing that the Jewish spcriptures be rejected by Christians. His views, however, were eventually rejected.

During the First Council of Nicaea in AD 325, the Roman emperor Constantine said,

... Let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd; for we have received from our Saviour a different way.[6]

Emperor Theodosius I in 391 banned pagan worship and in effect made Christianity the state religion of the Roman Empire. Bishop Ambrose of Milan contradicted this same Theodosius for being too supportive of the the rights of Jews when Theodosius ordered the rebuilding of a Jewish synogogue at church expense after a Christian mob had burned it. Ambrose argued that it was inappropriate for a Christian emperor protect the Jews in this way, saying sarastically: "You have the guilty man present, you hear his confession. I declare that I set fire to the synagogue, or at least that I ordered those who did it, that there might not be a place where Christ was denied."

In the fifth century, several of the homilies of the popular orator Saint John Chrysostom, Bishop of Antioch, were directed against the Jews and against Christians associating with them:

- "Shall I tell you of their plundering, their covetousness, their abandonment of the poor, their thefts, their cheating in trade? The whole day long will not be enough to give you an account of these things." (Homily I, VII, 1)

Prejudice against Jews in the Roman Empire was formalized in 438, when the Code of Theodosius II established Roman Catholic Christianity as the only legal religion in the Roman Empire. The Justinian Code a century later stripped Jews of many of their rights, and Church councils throughout the sixth and seventh century, including the Council of Orleans, further enforced anti-Jewish provisions. These restrictions began as early as 305, when, in Elvira, (now Granada), the first known laws of any church council against Jews appeared. Christian women were forbidden to marry Jews unless the Jew first converted to Catholicism. Jews were forbidden to extend hospitality to Catholics. In 589, in Catholic Spain, the Third Council of Toledo ordered that children born of marriage between Jews and Catholic be baptized by force. By the Twelfth Council of Toledo (681) a policy of forced conversion of all Jews was initiated (Liber Judicum, II.2 as given in Roth).[7] Thousands fled, and thousands of others converted to Roman Catholicism.

Anti-Semitism in the Middle Ages

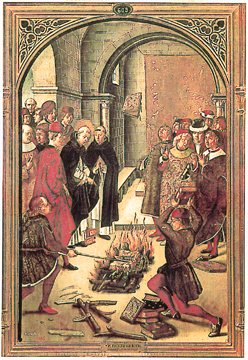

In the Middle Ages a main justification of prejudice against Jews in Europe was religious. However, this prejudice was just as violent as much of the racial anti-semitism of a later era. Jews faced villification as Christ-killers, suffered serious professional and economic restrictions, were accused of the most heinous crimes against Christians, had their books burned, were forced into ghettos, were required to wear disntinctive clothing, and faced explusions from several nations.

Deicide. Though not part of offcial Catholic dogma, many Christians, including members of the clergy, have held the Jewish people collectively responsible for rejecting and killing Jesus (see Deicide). This was a root cause for various other biases, suspicions, and accustations described below. Jews were considered arrogant, greedy, and self-righteous in their status as "chosen people." Ironically these prejudices led to a vicious cycle of policies with isolated the Jews and made them appear all the more alien to Christian majorities.

Passion plays. These dramatic stagings of the trial and death of Jesus, have historically been used in remembrance of Jesus' death during Lent. They usually depicted a racially stereotyped Judas cynically betraying Jesus for money, and a crowd Jews clamoring for Jesus' crucifixion while a Jewish leader assumed eternal collective Jewish guilt by declaring "his blood be on our heads!" For centuries, European Jews faced vicious attacks during lenten celebrations as Christian mobs vented their fury on Jews as "Christ-killers." [8]

Restrictions. Among socio-economic factors were restrictions by the authorities, local rulers, and frequently church officials. Jews were very often forbidden to own land, preventing them from farming. Because of their exlusion from guilds, most skilled trades were also closed to them, pushing them into marginal occupations considered socially inferior, such as tax- and rent-collecting or moneylending. Catholic doctrine of the time held that moneylending to one's fellow Christian for interest was a sin, and thus Jews tended to dominate this business. This provided support for stereotypic claims that Jews are insolent, greedy, involved in usury. Natural tensions between Jewish creditors and Christian debtors were added to social, political, religious, and economic strains. Peasants, who were often forced to pay their taxes and rents through Jewish agents, could villify them as the people taking their earnings while remaining loyal to the lords and rulers on whose behalf the Jews worked. The number of Jewish families permitted to reside in various places was limited; they were forcibly concentrated in ghettos; and they were subjected to discriminatory taxes on entering cities or districts other than their own.

Well Poisoning. Some Christians believed that Jews had gained special magical and sexual powers from making a deal with the devil against Christians. As the Black Death epidemics devastated Europe in the mid-14th century, rumors spread that Jews caused it by deliberately poisoning wells. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed by resulting violence. "In one such case, a man named Agimet was ... coerced to say that Rabbi Peyret of Chambery (near Geneva) had ordered him to poison the wells in Venice, Toulouse, and elsewhere. In the aftermath of Agimet’s "confession," the Jews of Strasbourg were burned alive on February 14, 1349.[9]

Host Desecration. Jews were also accused of torturing consecrated host wafers in a reenactment of the Crucifixion; this accusation was known as host desecration. Such charges sometimes resulted in serious persecutions (see picture at left).

Blood Libels. On other occasions, Jews were accused of a blood libel, the supposed drinking of blood of Christian children in mockery of the Christian Eucharist. The alleged procedure involved a child puberty being, tortured, and executed in a proceedure paralleling the supposed actions of the Jews who did likewise to Jesus. Among the documented cases of blood libels were:

- The story of young William of Norwich (d. 1144), the first known case of Jewish ritual murder alleged by a Christian monk.

- The case of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln (d. 1255) which alleged that after the boy was dead, his body was removed from the cross and laid on a table.

- The story of Simon of Trent (d. 1475), which emphasized how the boy was held over a large bowl so all his blood could be collected. (Simon was canonized by Pope Sixtus V in 1588. His cult was not officially disbanded until 1965 by Pope Paul VI.)

- In the 20th century, the Beilis Trial in Russia and the Kielce pogrom represented incidents of blood libel in Europe.

- More recently blood libel stories have appeared in the state-sponsored media of a number of Arab nations, in Arab television shows, and on websites.

Badges and Clothing. The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 was the first to proclaim the requirement for Jews to wear clothing that distinguished them as Jews. It could be a colored piece of cloth shpaed as a star or other emblem, a special hat (Judenhut), or a robe. Jews sought to evade the badges by paying what amounted to bribes in the form of temporary "exemptions" to kings, which were revoked and re-paid whenever the king needed to raise funds.

The Crusades

The Crusades were a series of several military campaigns sanctioned by the Papacy that took place during the 11th through 13th centuries. They began as Catholic endeavors to capture Jerusalem from the Muslims but developed into territorial wars.

Mobs accompanying the first three Crusades, anxious to spill "infidel" blood, attacked the Jewish communities in Germany, France, and England and put many Jews to death. Entire communities, like those of Treves, Speyer, Worms, Mayence, and Cologne, were massacred during the first Crusade by a mob army. The religious zeal fomented by the Crusades at times burned as fiercely against the Jews as against the Muslims, though attempts were made by bishops and the papacy to stop Jews from being attacked. Both economically and socially the Crusades were disastrous for European Jews.

Expulsions

England.To finance his war to conquer Wales, Edward I of England taxed the Jewish moneylenders. When the Jews could no longer pay, they were accused of disloyalty. Already restricted to a limited number of occupations, the Jews saw Edward abolish their "privilege" to lend money, choke their movements and activities and were forced to wear a yellow patch. The heads of Jewish households were then arrested, over 300 of them taken to the Tower of London and executed, while others killed in their homes. The complete banishment of all Jews from the country in 1290 led to thousands killed and drowned while fleeing. Jews were banned from England for three and a half centuries, until 1655, when Oliver Cromwell reversed the policy.

France. The practice of expelling the Jews accompanied by confiscation of their property, followed by temporary readmissions for ransom, was utilized to enrich the French crown during 12th-14th centuries. The most notable such expulsions were: from Paris by Philip Augustus in 1182, from the entirety of France by Louis IX in 1254, by Charles IV in 1322, by Charles V in 1359, by Charles VI in 1394.

Spain. In 1492, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile issued General Edict on the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain and thousands of Spain's substantial Sephardic Jewish population fled to the Ottoman Empire, others to the land of Israel/Palestine. Many Jews were later persecuted for secretly practicing their faith after pretending to convert to Chrisianity to avoid expulsion. (see also Spanish Inquisition)

Germany. In 1744, Frederick II of Prussia limited Breslau to only ten so-called "protected" Jewish families and encouraged similar practice in other Prussian cities. In 1750 he issued Revidiertes General Privilegium und Reglement vor die Judenschaft: the "protected" Jews had an alternative to "either abstain from marriage or leave Berlin" (quoting Simon Dubnow). In the same year, Archduchess of Austria Maria Theresa ordered Jews out of Bohemia but soon reversed her position, on condition that Jews pay for readmission every ten years. In 1752 she introduced the law limiting each Jewish family to one son. In 1782, Joseph II abolished most of persecution practices in his Toleranzpatent, on the condition that Yiddish and Hebrew be eliminated from public records and Jewish judicial autonomy is annulled.

- Note: the above summary deals only with national-level expulsions and only include local expulsions, pogroms, and forced ghettoization of countless other European Jews.

The Modern Era

The Reformation

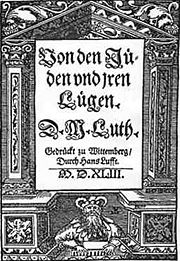

Although the Reformation was a harbinger of future religious liberty and tolerance, in the short term it did little to help the Jews. Martin Luther at first hoped that the Jews would ally with him against Rome and that his preaching of the true Gospel would convert them to Christ. When this did not come to pass he turned his pen against the Jews, writing some of Christianity's most anti-semitic lines. In On the Jews and their Lies, Luther proposes the permanent oppression and/or expulsion of the Jews. He calls for the burning of synagogues, saying: "First to set fire to their synagogues or schools and to bury and cover with dirt whatever will not burn, so that no man will ever again see a stone or cinder of them." He calls Jews "nothing but thieves and robbers who daily eat no morsel and wear no thread of clothing which they have not stolen and pilfered from us by means of their accursed usury." According to Paul Johnson, Luther's pamphlet "may be termed the first work of modern anti-Semitism, and a giant step forward on the road to the Holocaust."[10]

In his final sermon shortly before his death, however, Luther reversed himself and said: "We want to treat them with Christian love and to pray for them, so that they might become converted and would receive the Lord."[11] Still, Luther's harsh comments about the Jews are seen by many as a continuation of medieval Christian anti-Semitism.

Modern Catholicism

Throughout the 19th century and into the 20th centuries, the Catholic Church still incorporated strong anti-Semitic elements, despite increasing attempts to separate anti-Judaism — the opposition to the Jewish religion on religious grounds — and racial anti-Semitism. Pope Pius VII (1800-1823) had the walls of the Jewish Ghetto in Rome rebuilt after the Jews were released by Napoleon, and Jews were restricted to the Ghetto through the end of the papacy of Pope Pius IX (1846-1878), the last Pope to rule Rome. Pope Pius XII has been criticized for failing to act in defense of the Jews during the Hitler period. Until 1946 the Jesuits banned candidates "who are descended from the Jewish race unless it is clear that their father, grandfather, and great-grandfather have belonged to the Catholic Church." Since Vatican II, the Catholic Church has taken a stronger stand against anti-Semitism. Paul VI, in Nostra Aetate, declared that "what happened in His passion cannot be charged against all the Jews... then alive, nor against the Jews of today." Furthermore, the Catholic Church "decries hatred, persecutions, displays of anti-Semitism, directed against Jews at any time and by anyone." John Paul II went further by admitted that Christianity had done wrong in it's previous teachings concerning the Jews, admitting that by "blaming the Jews for the death of Jesus, certain Christian teachings had helped fuel anti-Semitism," and stating that ""no theological justification could ever be found for acts of discrimination or persecution against Jews. In fact, such acts must be held as sinful." [1]

Racial anti-Semitism

As the spirit of religious tolerance spread, racial anti-Semitism gradually superceded mere anti-Judaism. In the context of the Industrial Revolution, following the emancipation of the Jews, Jews rapidly urbanized and experienced a period of greater social mobility, contributing further to myth of Jewish wealth and greed. The advent of racial anti-Semitism was also linked to the growing sense of nationalism in many countries. The nationalist context viewed Jews as a separate and often "alien" nation within the countries in which Jews resided, a prejudice exploited by the elites of many governments.

The Dreyfus affair was a political scandal which divided France for many years during the late 19th century. It centered on the 1894 treason conviction of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army. Dreyfus was, in fact, innocent: the conviction rested on false documents, and when high-ranking officers realized this they attempted to cover up the mistakes. The Dreyfus Affair split France between the Dreyfusards (those supporting Alfred Dreyfus) and the Antidreyfusards (those against him).

Pogroms

Pogroms were a form of race riots, most commonly Russia and Eastern Europe, aimed specifically at Jews and often government sponsored. Pogroms became endemic during a large-scale wave of anti-Jewish riots that swept southern Russia in 1881, after Jews were wrongly blamed for the assassination of Tsar Alexander II. In the 1881 outbreak, thousands of Jewish homes were destroyed, many families reduced to extremes of poverty; women sexually assaulted, and large numbers of men, women, and children killed or injured in 166 Russian towns. The new tzar, Alexander III, blamed the Jews for the riots and issued a series of harsh restrictions on Jews. Large numbers of pogroms continued until 1884, with at least tacit inactivity by the authorities. An even bloodier wave of pogroms broke out in 1903-1906, leaving an estimated 2,000 Jews dead, and many more wounded. A final large wave of 887 pogroms in Russia and Ukraine occurred during the Russian Revolution of 1917, in which between 70,000 to 250,000 civilian Jews were killed by riots led by various sides.

During the early to mid-1900s, pogroms also occurred in Poland, Argentina, and throughout the Arab world. Extremely deadly pogroms also occurred during World War II, including the Romanian Iaşi pogrom in which 14,000 Jews were killed, and the Jedwabne massacre in Poland which killed between 380 and 1,600 Jews. The last mass pogrom in Europe was the post-war Kielce pogrom of 1946.

Anti-Jewish legislation

Anti-semitism was officially adopted by the German Conservative Party at the Tivoli Congress in 1892, on the instigation of Dr. Klasing but in the teeth of opposition led by the moderate Werner von Blumenthal.

Official anti-Semitic legislation was enacted in various countries, especially in Imperial Russia in the 19th century and in Nazi Germany and its Central European allies in the 1930s. These laws were passed against Jews as a group, regardless of their religious affiliation - in some cases, such as Nazi Germany, having a Jewish grandparent was enough to qualify someone as Jewish.

In Germany, the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 prevented marriage between any Jew and non-Jew, and made it that all Jews, even quarter- and half-Jews, were no longer citizens of their own country (their official title became "subject of the state"). This meant that they had no basic citizens' rights, e.g., to vote. In 1936, Jews were banned from all professional jobs, effectively preventing them having any influence in education, politics, higher education and industry. On 15 November of 1938, Jewish children were banned from going to normal schools. By April 1939, nearly all Jewish companies had either collapsed under financial pressure and declining profits, or had been persuaded to sell out to the Nazi government. This further reduced their rights as human beings; they were in many ways officially separated from the German populace. Similar laws existed in Hungary, Romania, and Austria.

The Holocaust

Racial anti-Semitism reached its most horrific manifestation in the Holocaust during World War II, in which about 6 million European Jews, 1.5 million of them children, were systematically murdered. Hitler taught the the Jews were basically a cancer on the body politic of Europe. A virulent anti-semitism was a central part of his ideology from the beginning, and hatred of Jews provided both a distraction from other problem and fuel for totalitarian engine that powered Nazi Germany.

The Nazi anti-Semitic program quickly expanded beyond mere hate speech. Starting in 1933, repressive laws were passed against Jews, culminating in the Nuremberg Laws (see above). Sporadic violence against the Jews became widespread with the Kristallnacht riots, which targeted Jewish homes, businesses and places of worship, killing hundreds across Germany and Austria. During the war, Jews were expelled from Germany and sent to concentration camps in other nations. Eventually, as Hitler expanded the German Reich into Eastern Europe, he determined that the Jews and other "inferior" people must be totally liquidated through a policy of efficient mass murder.

Space prevents a detailed discussion of the rise of Nazi anti-semitism and Hitler's "final solution" to the "Jewish Problem" here. Nor should the fact of the Nazi Holocaust blind us to the fact the Jews also suffered greatly the Soviet Union and that anti-semitism has continued to be a real problem in more recent years. Please see the related articles listed below for details.

New anti-Semitism

In recent years some scholars of history, psychology, religion, and representatives of Jewish groups, have noted what they describe as the new anti-Semitism, which is associated with the Left, rather than the Right, and which uses the language of anti-Zionism and criticism of Israel to attack the Jews more broadly.

Anti-Zionism is a term that has been used to describe several very different political and religious points of view (both historically and in current debates) all expressing some form of opposition to Zionism. A large variety of commentators - politicians, journalists, academics and others - believe that criticisms of Israel and Zionism are often disproportionate in degree and unique in kind, and attribute this to anti-Semitism. In turn, critics of this view believe that associating anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism is intended to stifle debate, deflect attention from valid criticism, and taint anyone opposed to Israeli actions and policies. (See Anti-Zionism.)

The European Commission on Racism and Intolerance formally defined some of the ways in which anti-Zionism may cross the line into anti-Semitism. "Examples of the ways in which anti-Semitism manifests itself with regard to the State of Israel taking into account the overall context could include:

- denying the Jewish people right to self-determination, e.g. by claiming that the existence of a state of Israel is a racist endeavor;

- applying double standards by requiring of it a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation;

- using the symbols and images associated with classic anti-Semitism (e.g. claims of Jews killing Jesus or blood libel, to characterize Israel or Israelis); and

- holding Jews collectively responsible for the actions of the State of Israel."

Muslims refer to Jews and Christians as a "People of the book" or Dhimmis. As such they are granted protection of life; the right to residence, worship, and work or trade. However, anti-Semitism in the Muslim world increased in the twentieth century, espeically as resentment against Zionist efforts in British Mandate of Palestine spread.

Anti-Zionist propaganda in the Middle Eas] frequently adopts the terminology and symbols of the Holocaust to demonize Israel and its leaders. At the same time, Holocaust denial and Holocaust minimization efforts have found increasingly overt acceptance as sanctioned historical discourse in a number of Middle Eastern countries.

Anti-Semitism in the 21st century

According to the 2005 U.S. State Department Report on Global Anti-Semitism, anti-Semitism in Europe has increased significantly in recent years. Beginning in 2000, verbal attacks directed against Jews increased while incidents of vandalism (e.g. graffiti, fire bombings of Jewish schools, desecration of synagogues and cemeteries) surged. Physical assaults including beatings, stabbings and other violence against Jews in Europe increased markedly, in a number of cases resulting in serious injury and even death.

On January 1, 2006, Britain's chief rabbi, Sir Jonathan Sacks, warned that what he called a "tsunami of anti-Semitism" was spreading globally. In an interview with BBC's Radio Four, Sacks said that anti-Semitism was on the rise in Europe, and that a number of his rabbinical colleagues had been assaulted, synagogues desecrated, and Jewish schools burned to the ground in France. He also said that: "People are attempting to silence and even ban Jewish societies on campuses on the grounds that Jews must support the state of Israel, therefore they should be banned, which is quite extraordinary because ... British Jews see themselves as British citizens. So it's that kind of feeling that you don't know what's going to happen next that's making ... some European Jewish communities uncomfortable."[12]

Much of the new European anti-Semitic violence can actually be seen as a spill over from the long running Israeli-Arab conflict since the majority of the perpetrators are from the large immigrant Arab communities in European cities. According to The Stephen Roth Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism and Racism, most of the current anti-Semitism comes from militant Islamist and Muslim groups, and most Jews tend to be assaulted in countries where groups of young Muslim immigrants reside.[13]

Similarly, in the Middle East, anti-Zionist propaganda frequently adopts the terminology and symbols of the Holocaust to demonize Israel and its leaders. This rhetoric often crosses the line separating the legitimate criticism of Israel and its policies to become anti-Semitic vilification posing as legitimate political commentary. At the same time, Holocaust denial and Holocaust minimization efforts find increasingly overt acceptance as sanctioned historical discourse in a number of Middle Eastern countries.

The problem of anti-Semitism is not only significant in Europe and in the Middle East, but there are also worrying expressions of it elsewhere. For example, in Pakistan, a country without a Jewish community, anti-Semitic sentiment fanned by anti-Semitic articles in the press is widespread. This reflects the more recent phenomenon of anti-Semitism appearing in countries where historically or currently there are few or even no Jews.

Related Artciles

Notes

- ↑ Chesler, Phyllis. The New Anti-Semitism: The Current Crisis and What We Must Do About It, Jossey-Bass, 2003, pp. 158-159, 181.

- ↑ Kinsella, Warren. The New anti-Semitism, accessed March 5, 2006.

- ↑ Lewis, Bernard.

- ↑ Schafer, Peter. Judeophobia, Harvard University Press, 1997, p 208.

- ↑ Van Der Horst, Pieter Willem. Philo's Flaccus: the First Pogrom, Philo of Alexandria Commentary Series, Brill, 2003.

- ↑ Eusebius. "Life of Constantine (Book III)", 337 C.E., accessed March 12, 2006.

- ↑ Roth, A. M. Roth, and Roth, Norman. Jews, Visigoths and Muslims in Medieval Spain, Brill Academic, 1994.

- ↑ Sennott, Charles M. "In Poland, new 'Passion' plays on old hatreds", The Boston Globe, April 10, 2004.

- ↑ Hertzberg, Arthur and Hirt-Manheimer, Aron. Jews: The Essence and Character of a People, HarperSanFrancisco, 1998, p.84. ISBN 0060638346

- ↑ Johnson, Paul. A History of the Jews, HarperCollins Publishers, 1987, p.242. ISBN 5551768589

- ↑ Luther, Martin. D. Martin Luthers Werke: kritische Gesamtausgabe, Weimar: Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, 1920, Vol. 51, p. 195.

- ↑ Gillan, Audrey. "Chief rabbi fears 'tsunami' of hatred", Guardian, January 2, 2006.

- ↑ "Annual Reports: General Analysis, 2004", The Steven Roth Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism and Racism, Tel Aviv University, accessed March 12, 2006.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bodansky, Yossef. Islamic Anti-Semitism as a Political Instrument, Freeman Center For Strategic Studies, 1999.

- Carr, Steven Alan. Hollywood and anti-Semitism: A cultural history up to World War II, Cambridge University Press 2001.

- Cohn, Norman. Warrant for Genocide, Eyre & Spottiswoode 1967; Serif, 1996.

- Freudmann, Lillian C. Antisemitism in the New Testament, University Press of America, 1994.

- Hilberg, Raul. The Destruction of the European Jews. Holmes & Meier, 1985. 3 volumes.

- Lipstadt, Deborah. Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory, Penguin, 1994.

- Prager, Dennis, Telushkin, Joseph. Why the Jews? The Reason for Antisemitism. Touchstone (reprint), 1985.

- Selzer, Michael (ed). "Kike!" : A documentary history of anti-semitism in America, New York 1972.

Further reading

- Why the Jews? A perspective on causes of anti-Semitism

- Coordination Forum for Countering Antisemitism (with up to date calendar of anti-semitism today)

- Annotated bibliography of anti-Semitism hosted by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem's Center for the Study of Antisemitism (SICSA)

- Anti-Semitism and responses

- The Stephen Roth Institute for the Study of Contemporary anti-Semitism and Racism hosted by the Tel Aviv University - (includes an annual report)

- Jews, the End of the Vertical Alliance, and Contemporary Antisemitism

- An Israeli point of view on antisemitism, by Steve Plaut

- The Anti-Semitic Disease - an analysis of Anti-Semitism by Paul Johnson in Commentary Magazine

- Council of Europe, ECRI Country-by-Country Reports

- State University of New York at Buffalo, The Jedwabne Tragedy

- Jews in Poland today

- Anti-Defamation League's report on International Anti-Semitism

- The Middle East Media Research Institute - documents antisemitism in Middle-Eastern media.

- Judeophobia: A short course on the history of anti-Semitism at [2] Zionism and Israel Information Center.

- Arab and Muslim Anti-Zionism and anti-Semitiem A mini study with extensive links and resources.

- If Not Together, How?: Research by April Rosenblum to develop a working definition of antisemitism, and related teaching tools about antisemitism, for activists.

- 'Anti-Semitism in Armenia is a Result of Hate against Israeli-Turkish Cooperation: Journal of Turkish weekly (JTW)

- Armenia’s Jewish Scepticism and Its Impact on Armenia-Israel Relations

- Rise of Anti-Semitism in Modern Armenia and Karabakh

- The Holocaust and Armenian Case: Highligting the Main Differences

- Armenian Anti-Semitism in the Ottoman Period

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.