Hemingway, Ernest

m (Hemingway, Ernest moved to Ernest Hemingway) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (53 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebapproved}}{{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Status}} |

| − | + | {{epname|Hemingway, Ernest}} | |

| − | + | [[File:Ernest Hemingway in Milan 1918.jpg|thumb|300px|A young Hemingway in his World War I uniform]] | |

| − | + | '''Ernest Miller Hemingway''' (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an [[United States|American]] [[novelist]] and short story writer whose works, drawn from his wide range of experiences in [[World War I]], the [[Spanish Civil War]], and [[World War II]], are characterized by terse [[minimalism]] and [[understatement]]. | |

| − | [[ | + | Hemingway's clipped prose style and unflinching treatment of human foibles represented a break with both the [[prosody]] and sensibilities of the nineteenth-century novel that preceded him. The urbanization of America, coupled with its emergence from isolation and entry into the first World War created a new, faster paced life that was at odds with the leisurely paced, rustic nineteenth-century novel. Hemingway seems to capture perfectly the new pace of life with his language. He catalogued America's entry into the world through the eyes of disaffected expatriated intellectuals in works like ''The Sun Also Rises'', as well as the longing for a more simple time in his classic ''The Old Man and the Sea.'' |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Hemingway exerted a significant influence on the development of twentieth-century [[fiction]], both in America and abroad. Echoes of his style can still be heard in the telegraphic prose of many contemporary novelists and screenwriters, as well as in the modern figure of the disillusioned anti-hero. Throughout his works, Hemingway sought to reconcile the ruination of his times with an enduring belief in conquest, triumph, and "grace under pressure." | ||

| − | + | ==Youth== | |

| − | + | [[Image:ErnestHemingwayBabyPicture.gif|thumb|200px|right|A baby picture, c. 1900]] | |

| − | + | Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899, in Oak Park, [[Illinois]], the firstborn son of six children. His mother was domineering and devoutly religious, mirroring the strict [[Protestant]] ethic of Oak Park, which Hemingway later said had "wide lawns and narrow minds." Hemingway adopted his father's outdoor interests—hunting and fishing in the woods and lakes of northern [[Michigan]]. Hemingway's early experiences in close contact with nature would instill in him a lifelong passion for outdoor isolation and adventure. | |

| − | [[ | + | When Hemingway graduated from high school, he did not pursue a college education. Instead, in 1916, when he was 17 years old, he began his writing career as a cub [[reporter]] for the ''[[Kansas City Star]].'' While he stayed at that newspaper for only about six months, throughout his lifetime he used the admonition from the ''Star'''s [[style guide]] as a foundation for his manner of writing: "Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English. Be positive, not negative."<ref>[https://citatis.com/a19368/2622dc/ Ernest Hemingway Quotes] ''Citatis''. Retrieved November 4, 2020.</ref> |

| − | Hemingway left his reporting job after only a few months, and, against his father's wishes, tried to join the [[United States Army]] to see action in [[World War I]]. He | + | ==World War I== |

| + | [[File:Ernest Hemingway recuperates from wounds in Milan, 1918.jpg|thumb|200px|Hemingway recuperating from wounds in [[Milan]], [[Italy,]] September 1918]] | ||

| + | Hemingway left his reporting job after only a few months, and, against his father's wishes, tried to join the [[United States Army]] to see action in [[World War I]]. He failed the medical examination, instead joining the [[American Field Service]] Ambulance Corps and leaving for [[Italy]], then fighting for the Allies. | ||

| − | Soon after arriving on the Italian front, he witnessed the brutalities of the war; on his first day of duty, an [[ammunition]] factory near [[Milan]] suffered an explosion. Hemingway had to pick up the human remains, mostly of women who had worked at the factory. This first cruel encounter with human death left him shaken | + | Soon after arriving on the Italian front, he witnessed the brutalities of the war; on his first day of duty, an [[ammunition]] factory near [[Milan]] suffered an explosion. Hemingway had to pick up the human remains, mostly of women who had worked at the factory. This first cruel encounter with human death left him shaken. |

| − | |||

| − | At the Italian front on July 8, 1918, Hemingway was wounded delivering supplies to soldiers, ending his career as an ambulance driver. | + | At the Italian front on July 8, 1918, Hemingway was wounded delivering supplies to soldiers, ending his career as an ambulance driver. After this experience, Hemingway convalesced in a Milan hospital run by the [[American Red Cross]]. There he was to meet a nurse, Sister Agnes von Kurowsky. The experience would later form the foundation for his first great novel, ''A Farewell to Arms.'' |

| − | + | ==First novels and other early works== | |

| − | + | Hemingway made his debut in American literature with the publication of the short story collection ''[[In Our Time]]'' (1925). The vignettes that now constitute the interchapters of the American version were initially published in Europe as ''in our time'' (1924). This work was important for Hemingway, reaffirming to him that his minimalist style could be accepted by the literary community. "The Big Two-Hearted River" is the collection's best-known story. | |

| − | + | It is the tale of a man, Nick Adams, who goes out camping along a river to fish, while at the same time suffering flashbacks to traumatic, wartime memories. Adams struggles with his grim experiences of death until he finds peace through the act of partaking in nature by coming to the river to fish. | |

| − | + | ==Life after WWI== | |

| + | After Hemingway's return to [[Paris]], [[Sherwood Anderson]] gave him a letter of introduction to [[Gertrude Stein]]. She became his mentor and introduced Hemingway to the "Parisian Modern Movement" then ongoing in [[Montparnasse Quarter]]. This group would form the foundation of the American expatriate circle that became known as the [[Lost Generation]]. | ||

| − | [[ | + | Hemingway's other influential mentor during this time was [[Ezra Pound]],<ref>On August 10, 1943, Hemingway typed a letter to [[Archibald MacLeish]] discussing Pound's mental health and other literary matters.</ref> the founder of [[imagism]]. Hemingway later said in reminiscence of this eclectic group: “Ezra was right half the time, and when he was wrong, he was so wrong you were never in any doubt about it. Gertrude was always right.”<ref> In a conversation with John Peale Bishop, quoted in Hemingway, Cowley (ed.), 1944, xiii.</ref> |

| − | + | During his time in Montparnasse, in just over six weeks, he wrote his second novel, ''[[The Sun Also Rises]]'' (1926). The semi-autobiographical novel, following a group of expatriate Americans in Europe, was successful and met with much critical acclaim. While Hemingway had initially claimed that the novel was an obsolete form of literature, he was apparently inspired to write one after reading [[F. Scott Fitzgerald|Fitzgerald]]'s manuscript for ''[[The Great Gatsby]].'' | |

| − | + | ==''A Farewell to Arms''== | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ''[[A Farewell to Arms]],'' is considered the greatest novel to come from Hemingway's experiences in WWI. It details the tragically doomed romance between Frederic Henry, an American soldier in convalescence, and Catherine Barkley, a British [[nurse]]. After recovering sufficiently from his wounds, Henry invites Barkley to run away with him, away from the war, to [[Switzerland]] and a life of peace, but their hopes are dashed: after a tumultuous escape across [[Lake Geneva]], Barkley, heavily pregnant, collapses and dies during labor. The novel closes with Henry's dark ruminations on his lost honor and love. | |

| − | + | The novel is heavily autobiographical: the plot is directly inspired by his experience with Sister von Kurowsky in Milan; the intense labor pains of his second wife, Pauline, in the birth of Hemingway's son inspired the depiction of Catherine's labor. | |

| − | '' | + | ==''The (First) Forty Nine Stories''== |

| − | + | Following the war and the publication of ''A Farewell to Arms,'' Hemingway wrote some of his most famous short stories. These stories were published in the collection ''[[The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories]].'' Hemingway's intention, as he openly stated in his own foreword to the collection, was to write more. He would, however, write only a handful of short stories during the rest of his literary career. | |

| − | + | Some of the collection's important stories include: ''Old Man at the Bridge,'' ''On The Quai at Smyrna,'' ''Hills Like White Elephants,'' ''One Reader Writes,'' ''The Killers,'' and (perhaps most famously) ''A Clean, Well-Lighted Place.'' While these stories are rather short, the book also includes much longer stories. Among these the most famous are ''The Snows of Kilimanjaro'' and ''The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.'' | |

| − | + | ==''For Whom the Bell Tolls''== | |

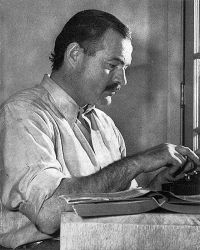

| − | + | [[File:ErnestHemingway.jpg|thumb|200px|left|Hemingway posing for a photo for the first edition of "For Whom the Bell Tolls", by Lloyd Arnold at the Sun Valley Lodge, Idaho, late 1939]] | |

| − | + | [[Francisco Franco]] and his fascist forces won the [[Spanish Civil War]] in the spring of 1939. ''[[For Whom The Bell Tolls]]'' (1940) published shortly after, was drawn extensively from Hemingway's experiences as a reporter covering the war for the ''Toronto Star.'' Based on real events, the novel follows three days in the life of Robert Jordan, an American dynamiter fighting with Spanish [[guerilla]]s on the side of the Republicans. Jordan is one of Hemingway's characteristic antiheroes: a drifter with no sense of belonging, who finds himself fighting in Spain more out of boredom than out of any allegiance to ideology. The novel begins with Jordan setting out on another mission to dynamite a bridge to prevent the Nationalist Army from taking the city of [[Madrid]]. When he encounters the Spanish rebels he is supposed to assist, however, a change occurs within him. Befriending the old man Anselmo and the boisterous matriarch Pilar, and falling in love with the beautiful young Maria, Jordan at last finds a sense of place and purpose amongst the doomed rebels. It is one of Hemingway's most notable accomplishments, and one of his most life-affirming works. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Francisco Franco]] won the [[Spanish Civil War]] in the spring of 1939. ''[[For Whom The Bell Tolls]]'' | ||

==World War II and its aftermath== | ==World War II and its aftermath== | ||

| − | The United States entered [[World War II]] on | + | The United States entered [[World War II]] on December 8, 1941, and for the first time in his life Hemingway is known to have taken an active part in a war. Aboard the ''Pilar,'' Hemingway and his crew were charged with sinking Nazi submarines off the coasts of [[Cuba]] and the United States. His actual role in this mission is dubious; his ex-wife Martha viewed the sub-hunting as an excuse for Hemingway to get gas and booze for fishing. |

| − | |||

| − | Aboard the ''Pilar'' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | After the war, Hemingway started work on ''[[The Garden of Eden]],'' which was never finished and would be published posthumously in a much abridged form in 1986. At one stage, he planned a major trilogy which was to be comprised of "The Sea When Young," "The Sea When Absent," and "The Sea in Being" (the latter eventually published in 1953 as ''The Old Man and the Sea''). There was also a "Sea-Chase" story; three of these pieces were edited and stuck together as the posthumously published novel ''[[Islands in the Stream]]'' (1970). | |

| − | In 1952, | + | ==''The Old Man and the Sea''== |

| + | [[File:Ernest Hemingway 1950 crop.jpg|thumb|200px|Hemingway aboard his yacht, circa 1950]] | ||

| + | In 1952, Hemingway published ''[[The Old Man and the Sea]].'' Often cited as his greatest work, the [[novella]]'s enormous success satisfied and fulfilled Hemingway probably for the last time in his life. It earned him both the [[Pulitzer Prize]] in 1953 and the [[Nobel Prize in Literature]] in 1954, and restored his international reputation, which had suffered after the disastrous publication of his over-the-top novel ''Across the River and Into the Trees.'' | ||

| − | + | ''The Old Man and the Sea'' is the story of an aging Cuban fisherman who sets off to fish for one last time despite his advancing age and the obsolescence of his traditional profession. The narrative proceeds rapidly using Hemingway's characteristic understatement to great effect, to the extent that it causes the reader to lose all sense of reading a work of fiction, but instead feel as though they are at sea. The fisherman encounters an enormous fish. Although he catches it, the effort nearly kills him. As he proceeds back to shore, schools of [[barracuda]] eat away at the body of the fish, so that by the time he returns the only thing the old man has to show for his struggle is the enormous fish's skeleton, bone dry. | |

| − | + | The novella is often interpreted as an allegory of religious struggle (the fish, of course, is a major figure in [[Christianity]]). The old man, though irrevocably changed by his experience on the sea, has nothing to physically show for it, and must be content to have nothing but the afterglow of an epiphany. In this sense there are considerable parallels to [[Fyodor Dostoevsky|Dostoevsky]]'s famous passage, ''[[The Grand Inquisitor]],'' a piece of literature Hemingway loved, where the Inquisitor relentlessly interrogates Christ, only to be left dumbfounded and silent by a sudden act of revelation. | |

| − | + | The story itself is also starkly existential and resists simple interpretation: though there is a sense of a certain transcendence in the old man's epic struggle, the narrative itself is arid and spartan. Hemingway seems to insist that beyond any [[allegory]], it is simply the tale of a man who went to sea and caught and lost a fish, and that this is the profoundest truth of all. | |

| − | + | ==Later Years and Death== | |

| + | Riding high on the success of his last great novel, Hemingway's notorious bad luck struck once again; on a safari he suffered injuries in two successive plane crashes. As if this were not enough, he was badly injured one month later in a [[bushfire]] accident which left him with [[burn (injury)|second degree burn]]s all over his body. The pain left him in prolonged anguish, and he was unable to travel to [[Stockholm]] to accept his [[Nobel Prize.]] | ||

| − | + | A glimmer of hope came with the discovery of some of his old manuscripts from 1928 in the Ritz cellars, which were transformed into ''[[A Moveable Feast]].'' Although some of his energy seemed to be restored, severe drinking problems kept him down. His blood pressure and cholesterol count were perilously high, he suffered from aortal inflammation, and his depression, aggravated by [[alcoholism]], worsened. | |

| + | [[File:Hemingway Memorial Sun Valley.jpg|thumb|200px|Ernest Hemingway Memorial above Trail Creek in Sun Valley, Idaho]] | ||

| + | Simultaneously, he also lost his beloved estate outside [[Havana]], [[Cuba]], that he had owned for over twenty years, forcing him into "exile" in Ketchum, [[Idaho]]. The famous photograph of [[Fidel Castro]] and Hemingway, nominally related to a fishing competition that Castro won, is believed to document a conversation in which Hemingway begged for the return of his estate, which Castro ignored. | ||

| − | Consumed with depression about these and other problems, Hemingway committed suicide on the morning of | + | Consumed with depression about these and other problems, Hemingway committed [[suicide]] at the age of 61 on the morning of July 2, 1961, as a result of a self-inflicted [[shotgun]] blast to the head. |

==Influence and legacy== | ==Influence and legacy== | ||

| + | The influence of Hemingway's writings on [[American literature]] was considerable and continues to exist today. Indeed, the influence of Hemingway's style was so widespread that it may be glimpsed in most contemporary fiction, as writers draw inspiration either from Hemingway himself or indirectly through writers who consciously emulated Hemingway's style. In his own time, Hemingway affected writers within his [[modernist]] literary circle. [[James Joyce]] called "A Clean, Well Lighted Place" "one of the best stories ever written." [[Pulp fiction]] and "hard boiled" crime fiction often owe a strong debt to Hemingway. | ||

| − | + | Hemingway's terse prose style is known to have inspired [[Bret Easton Ellis]], [[Chuck Palahniuk]], [[Douglas Coupland]], and many [[Generation X]] writers. Hemingway's style also influenced [[Jack Kerouac]] and other [[Beat Generation]] writers. [[J.D. Salinger]] is said to have wanted to be a great American [[short story]] writer in the same vein as Hemingway. | |

| − | |||

| − | Hemingway's terse prose style is known to have inspired [[Bret Easton Ellis]], [[Chuck Palahniuk]], [[Douglas Coupland]] and many [[Generation X]] writers. Hemingway's style also influenced [[Jack Kerouac]] and other [[Beat Generation]] writers. [[J.D. Salinger]] is said to have wanted to be a great American [[short story]] writer in the same vein as Hemingway. | ||

===Awards and honors=== | ===Awards and honors=== | ||

| Line 99: | Line 89: | ||

During his lifetime Hemingway was awarded with: | During his lifetime Hemingway was awarded with: | ||

*[[Silver Medal of Military Valor]] (medaglia d'argento) in [[World War I]] | *[[Silver Medal of Military Valor]] (medaglia d'argento) in [[World War I]] | ||

| − | *[[Bronze Star Medal|Bronze Star]] (War Correspondent-Military Irregular in [[World War II]]) in | + | *[[Bronze Star Medal|Bronze Star]] (War Correspondent-Military Irregular in [[World War II]]) in 1947 |

| − | *[[Pulitzer Prize]] in | + | *[[Pulitzer Prize]] in 1953 (for ''The Old Man and the Sea'') |

| − | *[[Nobel Prize in Literature]] in | + | *[[Nobel Prize in Literature]] in 1954 (''The Old Man and the Sea'' cited as a reason for the award) |

==Works== | ==Works== | ||

| Line 114: | Line 104: | ||

* (1952) ''[[The Old Man and the Sea]]'' | * (1952) ''[[The Old Man and the Sea]]'' | ||

* (1962) ''[[Adventures of a Young Man]]'' | * (1962) ''[[Adventures of a Young Man]]'' | ||

| − | * (1970) ''[[Islands in the Stream (Hemingway)]]'' | + | * (1970) ''[[Islands in the Stream (Hemingway)|Islands in the Stream]]'' |

* (1986) ''[[The Garden of Eden]]'' | * (1986) ''[[The Garden of Eden]]'' | ||

* (1999) ''[[True at First Light]]'' | * (1999) ''[[True at First Light]]'' | ||

| Line 140: | Line 130: | ||

===Film=== | ===Film=== | ||

* (1937) ''[[The Spanish Earth]]'' | * (1937) ''[[The Spanish Earth]]'' | ||

| − | * (1962) ''[[Adventures Of A Young Man]]'' is based on Hemingway's | + | * (1962) ''[[Adventures Of A Young Man]]'' is based on Hemingway's Nick Adams stories. (Also known as ''[[Hemingway's Adventures Of A Young Man]].'') |

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | *Berridge, H.R. ''Barron's Book Notes on Ernest Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms''. Stuttgart: Klett, 1990. ISBN 0812034120 |

| − | * | + | *Baker, Carlos. ''Hemingway: The Writer as Artist''. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972. ISBN 0691013055 |

| − | * | + | *Baker, Carlos (ed.). ''Ernest Hemingway: Critiques of Four Major Novels''. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1962. ISBN 0684411571 |

| − | * | + | *Burgess, Anthony. ''Ernest Hemingway and His World''. Norwich: Thames and Hudson, 1978. ISBN 0684185040 |

| − | * | + | *Hemingway, Ernest. Carlos Baker (ed.). ''Selected Letters 1917-1961''. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1981. ISBN 0743246896 |

| − | * | + | *Hemingway, Ernest. Malcolm Cowley (ed.). ''Hemingway: A Comprehensive Selection''. New York: Viking Press, 1944. |

| − | * | + | *Koch, Stephen. ''The Breaking Point: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and the Murder of Jose Robles''. New York: Counterpoint Press, 2005. ISBN 1582432805 |

| − | * | + | *Lynn, Kenneth Schuyler. ''Hemingway''. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995. ISBN 0674387325 |

| − | * | + | *Young, Philip. ''Ernest Hemingway''. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston, 1952. ISBN 0816601917 |

| − | + | ==External links== | |

| − | + | All links retrieved February 13, 2024. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* [http://www.timelesshemingway.com Timeless Hemingway] | * [http://www.timelesshemingway.com Timeless Hemingway] | ||

| − | + | * [http://www.pbs.org/hemingwayadventure Michael Palin's Hemingway Adventure.] Based on a PBS lecture series narrated by Michael Palin. | |

| − | * [http://www.pbs.org/hemingwayadventure Michael Palin's Hemingway Adventure] Based on a PBS lecture series narrated by Michael Palin. | ||

*[http://www.hemingwaysociety.org The Hemingway Society] | *[http://www.hemingwaysociety.org The Hemingway Society] | ||

| − | + | * [http://www.hemingwayhome.com/ Ernest Hemingway Home and Museum in Key West, Florida] official website | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | {{Nobel Prize in Literature Laureates 1951-1975}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * [http://www.hemingwayhome.com/ Ernest Hemingway Home and Museum in Key West, Florida | ||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] |

| + | [[Category:Writers and poets]] | ||

{{credit|32106763}} | {{credit|32106763}} | ||

Latest revision as of 19:32, 13 February 2024

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist and short story writer whose works, drawn from his wide range of experiences in World War I, the Spanish Civil War, and World War II, are characterized by terse minimalism and understatement.

Hemingway's clipped prose style and unflinching treatment of human foibles represented a break with both the prosody and sensibilities of the nineteenth-century novel that preceded him. The urbanization of America, coupled with its emergence from isolation and entry into the first World War created a new, faster paced life that was at odds with the leisurely paced, rustic nineteenth-century novel. Hemingway seems to capture perfectly the new pace of life with his language. He catalogued America's entry into the world through the eyes of disaffected expatriated intellectuals in works like The Sun Also Rises, as well as the longing for a more simple time in his classic The Old Man and the Sea.

Hemingway exerted a significant influence on the development of twentieth-century fiction, both in America and abroad. Echoes of his style can still be heard in the telegraphic prose of many contemporary novelists and screenwriters, as well as in the modern figure of the disillusioned anti-hero. Throughout his works, Hemingway sought to reconcile the ruination of his times with an enduring belief in conquest, triumph, and "grace under pressure."

Youth

Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899, in Oak Park, Illinois, the firstborn son of six children. His mother was domineering and devoutly religious, mirroring the strict Protestant ethic of Oak Park, which Hemingway later said had "wide lawns and narrow minds." Hemingway adopted his father's outdoor interests—hunting and fishing in the woods and lakes of northern Michigan. Hemingway's early experiences in close contact with nature would instill in him a lifelong passion for outdoor isolation and adventure.

When Hemingway graduated from high school, he did not pursue a college education. Instead, in 1916, when he was 17 years old, he began his writing career as a cub reporter for the Kansas City Star. While he stayed at that newspaper for only about six months, throughout his lifetime he used the admonition from the Star's style guide as a foundation for his manner of writing: "Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English. Be positive, not negative."[1]

World War I

Hemingway left his reporting job after only a few months, and, against his father's wishes, tried to join the United States Army to see action in World War I. He failed the medical examination, instead joining the American Field Service Ambulance Corps and leaving for Italy, then fighting for the Allies.

Soon after arriving on the Italian front, he witnessed the brutalities of the war; on his first day of duty, an ammunition factory near Milan suffered an explosion. Hemingway had to pick up the human remains, mostly of women who had worked at the factory. This first cruel encounter with human death left him shaken.

At the Italian front on July 8, 1918, Hemingway was wounded delivering supplies to soldiers, ending his career as an ambulance driver. After this experience, Hemingway convalesced in a Milan hospital run by the American Red Cross. There he was to meet a nurse, Sister Agnes von Kurowsky. The experience would later form the foundation for his first great novel, A Farewell to Arms.

First novels and other early works

Hemingway made his debut in American literature with the publication of the short story collection In Our Time (1925). The vignettes that now constitute the interchapters of the American version were initially published in Europe as in our time (1924). This work was important for Hemingway, reaffirming to him that his minimalist style could be accepted by the literary community. "The Big Two-Hearted River" is the collection's best-known story.

It is the tale of a man, Nick Adams, who goes out camping along a river to fish, while at the same time suffering flashbacks to traumatic, wartime memories. Adams struggles with his grim experiences of death until he finds peace through the act of partaking in nature by coming to the river to fish.

Life after WWI

After Hemingway's return to Paris, Sherwood Anderson gave him a letter of introduction to Gertrude Stein. She became his mentor and introduced Hemingway to the "Parisian Modern Movement" then ongoing in Montparnasse Quarter. This group would form the foundation of the American expatriate circle that became known as the Lost Generation.

Hemingway's other influential mentor during this time was Ezra Pound,[2] the founder of imagism. Hemingway later said in reminiscence of this eclectic group: “Ezra was right half the time, and when he was wrong, he was so wrong you were never in any doubt about it. Gertrude was always right.”[3]

During his time in Montparnasse, in just over six weeks, he wrote his second novel, The Sun Also Rises (1926). The semi-autobiographical novel, following a group of expatriate Americans in Europe, was successful and met with much critical acclaim. While Hemingway had initially claimed that the novel was an obsolete form of literature, he was apparently inspired to write one after reading Fitzgerald's manuscript for The Great Gatsby.

A Farewell to Arms

A Farewell to Arms, is considered the greatest novel to come from Hemingway's experiences in WWI. It details the tragically doomed romance between Frederic Henry, an American soldier in convalescence, and Catherine Barkley, a British nurse. After recovering sufficiently from his wounds, Henry invites Barkley to run away with him, away from the war, to Switzerland and a life of peace, but their hopes are dashed: after a tumultuous escape across Lake Geneva, Barkley, heavily pregnant, collapses and dies during labor. The novel closes with Henry's dark ruminations on his lost honor and love.

The novel is heavily autobiographical: the plot is directly inspired by his experience with Sister von Kurowsky in Milan; the intense labor pains of his second wife, Pauline, in the birth of Hemingway's son inspired the depiction of Catherine's labor.

The (First) Forty Nine Stories

Following the war and the publication of A Farewell to Arms, Hemingway wrote some of his most famous short stories. These stories were published in the collection The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories. Hemingway's intention, as he openly stated in his own foreword to the collection, was to write more. He would, however, write only a handful of short stories during the rest of his literary career.

Some of the collection's important stories include: Old Man at the Bridge, On The Quai at Smyrna, Hills Like White Elephants, One Reader Writes, The Killers, and (perhaps most famously) A Clean, Well-Lighted Place. While these stories are rather short, the book also includes much longer stories. Among these the most famous are The Snows of Kilimanjaro and The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.

For Whom the Bell Tolls

Francisco Franco and his fascist forces won the Spanish Civil War in the spring of 1939. For Whom The Bell Tolls (1940) published shortly after, was drawn extensively from Hemingway's experiences as a reporter covering the war for the Toronto Star. Based on real events, the novel follows three days in the life of Robert Jordan, an American dynamiter fighting with Spanish guerillas on the side of the Republicans. Jordan is one of Hemingway's characteristic antiheroes: a drifter with no sense of belonging, who finds himself fighting in Spain more out of boredom than out of any allegiance to ideology. The novel begins with Jordan setting out on another mission to dynamite a bridge to prevent the Nationalist Army from taking the city of Madrid. When he encounters the Spanish rebels he is supposed to assist, however, a change occurs within him. Befriending the old man Anselmo and the boisterous matriarch Pilar, and falling in love with the beautiful young Maria, Jordan at last finds a sense of place and purpose amongst the doomed rebels. It is one of Hemingway's most notable accomplishments, and one of his most life-affirming works.

World War II and its aftermath

The United States entered World War II on December 8, 1941, and for the first time in his life Hemingway is known to have taken an active part in a war. Aboard the Pilar, Hemingway and his crew were charged with sinking Nazi submarines off the coasts of Cuba and the United States. His actual role in this mission is dubious; his ex-wife Martha viewed the sub-hunting as an excuse for Hemingway to get gas and booze for fishing.

After the war, Hemingway started work on The Garden of Eden, which was never finished and would be published posthumously in a much abridged form in 1986. At one stage, he planned a major trilogy which was to be comprised of "The Sea When Young," "The Sea When Absent," and "The Sea in Being" (the latter eventually published in 1953 as The Old Man and the Sea). There was also a "Sea-Chase" story; three of these pieces were edited and stuck together as the posthumously published novel Islands in the Stream (1970).

The Old Man and the Sea

In 1952, Hemingway published The Old Man and the Sea. Often cited as his greatest work, the novella's enormous success satisfied and fulfilled Hemingway probably for the last time in his life. It earned him both the Pulitzer Prize in 1953 and the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954, and restored his international reputation, which had suffered after the disastrous publication of his over-the-top novel Across the River and Into the Trees.

The Old Man and the Sea is the story of an aging Cuban fisherman who sets off to fish for one last time despite his advancing age and the obsolescence of his traditional profession. The narrative proceeds rapidly using Hemingway's characteristic understatement to great effect, to the extent that it causes the reader to lose all sense of reading a work of fiction, but instead feel as though they are at sea. The fisherman encounters an enormous fish. Although he catches it, the effort nearly kills him. As he proceeds back to shore, schools of barracuda eat away at the body of the fish, so that by the time he returns the only thing the old man has to show for his struggle is the enormous fish's skeleton, bone dry.

The novella is often interpreted as an allegory of religious struggle (the fish, of course, is a major figure in Christianity). The old man, though irrevocably changed by his experience on the sea, has nothing to physically show for it, and must be content to have nothing but the afterglow of an epiphany. In this sense there are considerable parallels to Dostoevsky's famous passage, The Grand Inquisitor, a piece of literature Hemingway loved, where the Inquisitor relentlessly interrogates Christ, only to be left dumbfounded and silent by a sudden act of revelation.

The story itself is also starkly existential and resists simple interpretation: though there is a sense of a certain transcendence in the old man's epic struggle, the narrative itself is arid and spartan. Hemingway seems to insist that beyond any allegory, it is simply the tale of a man who went to sea and caught and lost a fish, and that this is the profoundest truth of all.

Later Years and Death

Riding high on the success of his last great novel, Hemingway's notorious bad luck struck once again; on a safari he suffered injuries in two successive plane crashes. As if this were not enough, he was badly injured one month later in a bushfire accident which left him with second degree burns all over his body. The pain left him in prolonged anguish, and he was unable to travel to Stockholm to accept his Nobel Prize.

A glimmer of hope came with the discovery of some of his old manuscripts from 1928 in the Ritz cellars, which were transformed into A Moveable Feast. Although some of his energy seemed to be restored, severe drinking problems kept him down. His blood pressure and cholesterol count were perilously high, he suffered from aortal inflammation, and his depression, aggravated by alcoholism, worsened.

Simultaneously, he also lost his beloved estate outside Havana, Cuba, that he had owned for over twenty years, forcing him into "exile" in Ketchum, Idaho. The famous photograph of Fidel Castro and Hemingway, nominally related to a fishing competition that Castro won, is believed to document a conversation in which Hemingway begged for the return of his estate, which Castro ignored.

Consumed with depression about these and other problems, Hemingway committed suicide at the age of 61 on the morning of July 2, 1961, as a result of a self-inflicted shotgun blast to the head.

Influence and legacy

The influence of Hemingway's writings on American literature was considerable and continues to exist today. Indeed, the influence of Hemingway's style was so widespread that it may be glimpsed in most contemporary fiction, as writers draw inspiration either from Hemingway himself or indirectly through writers who consciously emulated Hemingway's style. In his own time, Hemingway affected writers within his modernist literary circle. James Joyce called "A Clean, Well Lighted Place" "one of the best stories ever written." Pulp fiction and "hard boiled" crime fiction often owe a strong debt to Hemingway.

Hemingway's terse prose style is known to have inspired Bret Easton Ellis, Chuck Palahniuk, Douglas Coupland, and many Generation X writers. Hemingway's style also influenced Jack Kerouac and other Beat Generation writers. J.D. Salinger is said to have wanted to be a great American short story writer in the same vein as Hemingway.

Awards and honors

During his lifetime Hemingway was awarded with:

- Silver Medal of Military Valor (medaglia d'argento) in World War I

- Bronze Star (War Correspondent-Military Irregular in World War II) in 1947

- Pulitzer Prize in 1953 (for The Old Man and the Sea)

- Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954 (The Old Man and the Sea cited as a reason for the award)

Works

Novels

- (1925) The Torrents of Spring

- (1926) The Sun Also Rises

- (1929) A Farewell to Arms

- (1937) To Have and Have Not

- (1940) For Whom the Bell Tolls

- (1950) Across the River and Into the Trees

- (1952) The Old Man and the Sea

- (1962) Adventures of a Young Man

- (1970) Islands in the Stream

- (1986) The Garden of Eden

- (1999) True at First Light

- (2005) Under Kilimanjaro

Nonfiction

- (1932) Death in the Afternoon

- (1935) Green Hills of Africa

- (1960) The Dangerous Summer

- (1964) A Moveable Feast

Short story collections

- (1923) Three Stories and Ten Poems

- (1925) In Our Time

- (1927) Men Without Women

- (1932) The Snows of Kilimanjaro

- (1933) Winner Take Nothing

- (1938) The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories

- (1947) The Essential Hemingway

- (1953) The Hemingway Reader

- (1972) The Nick Adams Stories

- (1976) The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway

- (1995) Collected Stories

Film

- (1937) The Spanish Earth

- (1962) Adventures Of A Young Man is based on Hemingway's Nick Adams stories. (Also known as Hemingway's Adventures Of A Young Man.)

Notes

- ↑ Ernest Hemingway Quotes Citatis. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ↑ On August 10, 1943, Hemingway typed a letter to Archibald MacLeish discussing Pound's mental health and other literary matters.

- ↑ In a conversation with John Peale Bishop, quoted in Hemingway, Cowley (ed.), 1944, xiii.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Berridge, H.R. Barron's Book Notes on Ernest Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms. Stuttgart: Klett, 1990. ISBN 0812034120

- Baker, Carlos. Hemingway: The Writer as Artist. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972. ISBN 0691013055

- Baker, Carlos (ed.). Ernest Hemingway: Critiques of Four Major Novels. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1962. ISBN 0684411571

- Burgess, Anthony. Ernest Hemingway and His World. Norwich: Thames and Hudson, 1978. ISBN 0684185040

- Hemingway, Ernest. Carlos Baker (ed.). Selected Letters 1917-1961. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1981. ISBN 0743246896

- Hemingway, Ernest. Malcolm Cowley (ed.). Hemingway: A Comprehensive Selection. New York: Viking Press, 1944.

- Koch, Stephen. The Breaking Point: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and the Murder of Jose Robles. New York: Counterpoint Press, 2005. ISBN 1582432805

- Lynn, Kenneth Schuyler. Hemingway. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995. ISBN 0674387325

- Young, Philip. Ernest Hemingway. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston, 1952. ISBN 0816601917

External links

All links retrieved February 13, 2024.

- Timeless Hemingway

- Michael Palin's Hemingway Adventure. Based on a PBS lecture series narrated by Michael Palin.

- The Hemingway Society

- Ernest Hemingway Home and Museum in Key West, Florida official website

|

1951: Pär Lagerkvist | 1952: François Mauriac | 1953: Winston Churchill | 1954: Ernest Hemingway | 1955: Halldór Laxness | 1956: Juan Ramón Jiménez | 1957: Albert Camus | 1958: Boris Pasternak | 1959: Salvatore Quasimodo | 1960: Saint-John Perse | 1961: Ivo Andrić | 1962: John Steinbeck | 1963: Giorgos Seferis | 1964: Jean-Paul Sartre | 1965: Michail Aleksandrovich Sholokhov | 1966: Shmuel Yosef Agnon, Nelly Sachs | 1967: Miguel Ángel Asturias | 1968: Yasunari Kawabata | 1969: Samuel Beckett | 1970: Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn | 1971: Pablo Neruda | 1972: Heinrich Böll | 1973: Patrick White | 1974: Eyvind Johnson, Harry Martinson | 1975: Eugenio Montale |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.