Difference between revisions of "Social theory" - New World Encyclopedia

(copied from Wikipedia) |

m |

||

| (29 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Sociology]] | [[Category:Sociology]] | ||

| + | {{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}} | ||

| + | {{Sociology}} | ||

| + | '''Social theory''' refers to the use of abstract and often complex theoretical frameworks to describe, explain, and analyze the social world. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | A good social theory reveals things that otherwise remain hidden. It also makes predictions about future actions, activity or situations. In general, the appeal of social theory derives from the fact that it takes the focus away from the individual (which is how most humans look at the world) and focuses it on the society itself and the social forces that affect our lives. This [[sociology|sociological]] insight (often termed the "sociological imagination") looks beyond the assumption that [[social structure]]s and patterns are purely random, and attempts to provide greater understanding and meaning to human existence. To succeed in this endeavor, social theorists, from time to time, incorporate methodologies and insights from a variety of disciplines. | ||

| + | == Introduction == | ||

| − | ''' | + | Although many commentators consider '''social theory''' a branch of [[sociology]], it has several interdisciplinary facets. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, other areas of the [[social sciences]], such as [[anthropology]], [[political science]], [[economics]], and [[social work]] branched out into their own disciplines, while social theory developed and flourished within sociology. Sociological subjects related to understanding society and its development became part of social theory. During this period, social theory by and large reflected traditional views of society, including traditional views of [[family]] and [[marriage]]. |

| − | + | Attempts at an interdisciplinary discussion free of the restrictions imposed by the more scientifically oriented disciplines began in the late 1920s. The [[Frankfurt School|Frankfurt Institute for Social Research]] provided the most successful example. The Committee on Social Thought at the [[University of Chicago]] followed in the 1940s. In the 1970s, programs in Social and Political Thought were established at Sussex and York College. Others followed, with various different emphases and structures, such as Social Theory and History ([[University of California|University of California, Davis]]). Cultural Studies programs, notably that of Birmingham University, extended the concerns of social theory into the domain of [[culture]] and thus [[anthropology]]. A chair and undergraduate program in social theory was established at the University of Melbourne and a number of universities began to specialize in social theory. | |

| − | + | Meanwhile, social theory continued to be used within sociology, [[economics]], and related [[social sciences]] that had no objections to scientific restrictions. | |

| − | ==Social | + | == History == |

| + | === Pre-classical Social Theorists === | ||

| − | [[ | + | Prior to the nineteenth century, social theory was largely narrative and [[norm]]ative, expressed in story form, with [[ethics|ethical]] principles and moral acts. Thus [[religion|religious]] figures can be regarded as the earliest social theorists. In [[China]], Master Kong (otherwise known as [[Confucius]] or Kung Fu-tzu) (551–479 <small>B.C.E.</small>) envisaged a just society that improved upon the Warring States. Later in China, [[Mozi]] (c. 470 – c. 390 <small>B.C.E.</small>) recommended a more pragmatic, but still ethical, sociology. In [[Greece]], [[philosophy|philosophers]] [[Plato]] (427–347 <small>B.C.E.</small>) and [[Aristotle]] (384–322 <small>B.C.E.</small>) were known for their commentaries on social order. In the [[Christianity|Christian]] world, [[Augustine of Hippo|Saint Augustine]] (354–430) and [[Thomas Aquinas]] (c. 1225–1274) concerned themselves exclusively with a just society. St. Augustine, who saw the late [[Ancient Rome|Ancient Roman]] society as corrupt, theorized a contrasting "City of God." |

| + | [[Europe]]an philosophers also theorized about society and contributed important ideas to the development of social theory. [[Thomas Hobbes]] (1588–1679) saw the social order as being created by people who have the right to withdraw their consent to a [[monarchy]]. [[John Locke]] (1632–1704) recognized that people can agree to work together. Baron de [[Montesquieu]] (1689–1775) postulated a natural social law that could be observed. [[Jean-Jacques Rousseau]] (1712–1778) believed that people working together can create the laws needed to establish a good society. [[Edmund Burke]] (1729–1797) saw society is an organic whole. [[Immanuel Kant]] (1724–1804) believed that only the rational, moral person, not ruled by passion, can be free. [[Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel]] (1770–1831) described the way in which rationality and morality develop together as people reflect on society. | ||

| − | + | The early thinkers were concerned with establishing an ideal society, however, not analyzing society as it exists. A notable exception was [[Ibn Khaldun]] (1332–1406), a [[Islam|Muslim]] philosopher and statesman from [[Egypt]] and [[Tunisia]]. In his book ''Al Muqaddimah'', (or ''The Introduction to History'') he analyzed the policies that led to the rise and fall of dynasties, explaining that in the [[Arab]] world the conquering [[nomad]]s originally settled in the towns. Later, when the invaders lost their [[desert]] skills and adopted the vices and slackness of town life, they become ripe for a new group of conquering nomads. His contemporaries ignored his theories, but they found their way into Western commentaries on national wealth. | |

| − | + | Hegel was the European philosopher who most influenced modern social analysts. ''Phenomenology of Spirit'' (sometimes translated ''Phenomenology of Mind'') is his description of social development through thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. This can be seen at work in a group that has a fixed set of ideas about the world. The more ardently the group presses their ideas, the more likely another group will challenge them. Both groups are likely to be somewhat extreme. Over time, a middle view that incorporates aspects of each group develops and is accepted by society. Thus does a society refine itself and progress towards ever more sophisticated concepts of life and morality. | |

| − | + | === Classical Social Theory === | |

| − | + | More elaborate social theories (known as classical theories) were developed by [[Europe]]an thinkers after several centuries of drastic social change in Western Europe. The [[Reformation]], [[Renaissance]] and the [[Age of Enlightenment|Enlightenment]] were followed by [[industrialization]], [[urbanization]] and [[democracy]]. Traditional ways of life were crumbling. The authority of the [[church]], the [[king]], and the upper [[social class|class]]es was challenged, [[family|families]] were separated by the migration to the [[city]], and previously self-sufficient farmers became dependent upon others for their daily needs. New means of [[transportation]] and [[communication]] increased the speed of change, and the individual came to be seen as a person worthy of rights and privileges. | |

| − | + | The classical theorists tried to make sense of all of these changes. Their theories are known as “grand theories”—comprehensive views that attempted to explain all of society with a single set of concepts. They usually included the [[Christianity|Christian]] idea of "social progress" and [[religion|religious]] elements, although the theorists themselves were not necessarily religious. They also included [[science]] and [[technology]], either as a saving [[grace]] or something to be feared. Many of the classical theorists had [[university]] appointments: [[Emile Durkheim]] was the first to have a [[sociology]] appointment. | |

| − | + | [[Auguste Comte]] (1798–1857), considered the "father of sociology," developed the theory of "Human Progress," in which development started with the [[theology|theological]] stage in which people attribute the cause of social events to [[God]]. In the [[metaphysics|metaphysical]] stage people are more realistic, and in the [[positivism|positivistic]] stage they come to understand life in terms of empirical evidence and science. This theory was popularized by [[Harriet Martineau]] (1802–1876), who translated Comte's work into English. A social theorist in her own right, Martineau's theories remained largely unknown for many years. | |

| − | + | The theory of social evolution known as [[social Darwinism]] was developed by | |

| + | [[Herbert Spencer]] (1820–1903). It was Spencer, not [[Charles Darwin|Darwin]], who coined the famous term "survival of the fittest," which he used to explain social inequalities. His lesser-known theory, the Law of Individuation, contends that each person develops into own separate [[identity]]. A fierce advocate of personal freedom and development, Spencer believed that the state ultimately existed to protect the rights of the individual. | ||

| − | + | [[Marxism]] is the theory of social inequality developed by Karl Marx (1818–1883), who claimed he turned Hegel “on its head.” Concerned about the consequences of industrial development, Marx advocated a revolution of the working class to overthrow the ruling [[capitalism|capitalists]]. The political components of his theory inspired a number of revolutions around the world including the [[Russian Revolution of 1917]]. Although Marx was a contemporary of Spencer and Comte, his social theory did not become popular until the twentieth century. | |

| − | The | + | The idea of a "collective conscious" (the [[belief]]s and sentiments of a group), reminiscent of Hegel, came from [[Emile Durkheim]], who thought that a person is not truly human without the social. Durkheim viewed [[norms]], the unwritten and unspoken rules of behavior that guide social interaction, as essential to a healthy society. Without them, ''[[anomie]]'', or a state of normlessness, when a society is unable to provide guidance results, and persons experiencing ''[[anomie]]'' feel lost and are susceptible to ''suicide''. “[[Sacred]],” “profane” (not sacred) and “[[totem]]” (an external representation of the collective spiritual experience) are significant concepts from his theory of [[religion]]. He predicted a future age of individual religion—“the cult of the individual”—when people internalize and revise collective totems for their own inner needs. |

| − | + | In ''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism'', [[Max Weber]] (1864–1920) predicted that the external pursuit of wealth, even if taken as evidence of God’s approval (as it was for the [[Calvinism|Calvinists]]), would become a cage of mundane passions. Weber was also concerned about the effects of rational authority, especially as found in [[bureaucracy]]. | |

| − | + | Other classical theories include the ideas of [[Vilfredo Pareto]] (1848–1923) and [[Pitirim Sorokin]], who were skeptical of [[technology]] and argued that progress is an illusion. Their social cycle theory illustrated the point that history is really a cycle of ups and downs. [[Ferdinand Tönnies]] (1855–1936) focused on "community" and "society," developing the concepts of [[Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft]] to describe the contrast between personal, intimate relationships and impersonal, bureaucratic ones. | |

| − | + | === Modern Social Theory === | |

| − | " | + | By and large, the classical theorists were strongly "structural-functional:" they tended to see society as an integrated system of stable social patterns {[[social structure]]}. Society was often compared to a living organism, with [[custom]]s and activities filling different functions or needs. |

| − | + | Early in the twentieth century, social theory began to include free will, individual choice, and subjective [[reasoning]]. Instead of classical [[determinism]], human activity was acknowledged to be unpredictable. Thus social theory became more complex. The "symbolic interactionist" perspective of [[George Herbert Mead]] (1863–1931) argued that individuals, rather than being determined by their environment, helped shape it. Individual [[identity]] and their [[role]]s in relationships are a key aspect of this theory. | |

| − | + | The "social conflict" perspective, based on [[Karl Marx|Marx]]’s theory, focused on the unequal distribution of physical resources and social rewards, particularly among groups differentiated by race, gender, [[social class|class]], age, and ethnicity. Since it included studies of prejudice and discrimination, it not surprisingly became a favorite of women and minorities. Conflict theorists believe that those in power created society’s rules for their own benefit and, therefore, that conflict and confrontation may be necessary to bring [[social change]]. | |

| − | + | These three perspectives became the dominant paradigms within [[sociology]] during the twentieth century. Each paradigm represents an historical development and new areas of exploration about society. Generally, theorists have advocated one perspective over the others. | |

| − | + | == Later Developments == | |

| − | + | The latter part of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century saw the emergence of several new types of social theory, building on previous approaches but incorporating new ideas both from within [[sociology]] and the [[social sciences]], but also from more distant fields in the [[science|physical]] and [[life science]]s, as well as incorporating new [[philosophy|philosophical]] orientations. | |

| − | + | === Systems Theory === | |

| − | + | [[Systems theory]] is one of the theoretical trends that developed in the late twentieth century that is truly interdisciplinary. In general, it is structural, but always holistic—a system cannot be understood by understanding the parts. Interaction and relationships are essential to a complete understanding of a social system. Systems theories are not reductionist, and they tend toward non-linearity and indeterminacy. In these ways they reject traditional scientific concepts, although most systems theorists still subscribe to time honored scientific methods. | |

| − | + | [[Talcott Parsons]]’ (1902–1979) systems theory dominated [[sociology]] from 1940 to 1970. It was a grand systems theory, wherein each system was composed of actors, goals and values, boundaries and patterns of interaction. His theory included the idea of human agency. A co-author of Parson's "Toward a General Theory of Action" was Edward Shils (1911–1995), who subsequently became concerned about the dumbing down, politicization and compromises within the intellectual life. For Shils, a civil society is an important mediator between the state and the individual. | |

| − | + | The [[biology|biologist]] [[Ludwig von Bertalanffy]] (1901–1972), whose General Systems Theory appeared almost simultaneously with Parson’s theory, believed his theory would be a new paradigm to guide model construction in all the sciences. He sought to capture the dynamic life processes in theoretical terms, using concepts such as open systems, equilibrium, system maintenance, and hierarchical organization. His theory gained wide recognition in both the physical and social sciences and is often associated with [[cybernetics]], a mathematical theory of [[communication]] and regulatory feedback developed by W. Ross Ashby and [[Norbert Wiener]] in the 1940s and 1950s. | |

| − | + | The Living Systems Theory developed by James Grier Miller (1916–2002) focused on characteristics unique to living systems—open, self-organizing systems that interact with their environment. Walter Buckley (1921–2005) focused on psychological and sociocultural systems, drawing distinctions between the simple mechanical systems of physical science with no feedback loops, and the complex adaptive systems that have feedback loops, are self regulatory, and exchange information and energy with the environment. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Network theory grew out of the studies of British [[anthropology|anthropologists]] (Elizabeth Bott and others) in the 1950s, using Moreno’s [[sociometry]] and other graphic models from [[social psychology]], as well as [[cybernetics]] and [[mathematics|mathematical]] concepts, to chart relationship patterns. Network theory appeals especially to macrotheorists who are interested in [[community]] and nation power structures. Related to network is exchange theory&madash;a theory that started as a behavioralistic theory with George C. Homans (1910-1989) and expanded to include power, equity, and justice (Richard Emerson, Karen Cook), as well as the sources of strain and conflict in micro and macro situations (Peter Blau). | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | Niklas Luhmann (1927-1998) used systems to describe society, but his approach is less deterministic than the theories above. He envisioned a self-organizing, living system with no central coordination. Such a system is created by the choices that people make, and trust and risk are key components. | |

| − | + | In the 1970s, [[René Thom]] introduced the idea of bifurcation—a state of system overload created by multiple feedback channels—through his development of [[catastrophe theory]]. In this situation, a deterministic system can generate two or more solutions. Non-linear phenomena were further examined in the 1980s in [[chaos theory]]. Developed by theorists from a range of disciplines—[[mathematics]], [[technology]], [[biology]], and [[philosophy]]—chaos theory spread to all academic disciplines. [[Complexity]] theory that followed was a return to more deterministic principles. With the idea of [[emergence]], or system choice, the line between living and non-living things became blurred. | |

| − | + | === Neo Marxism === | |

| − | + | Critical theory came from members of the [[Frankfurt School]] ([[Theodore Adorno]] (1903–1969), [[Max Horkheimer]] (1895–1973), [[Herbert Marcuse]] (1898–1979), [[Eric Fromm]] (1900–1980), [[Jurgen Habermas]] (1929–) and others). They began their work in the 1920s but it did not become well-known until the 1960s. They were severe critics of [[capitalism]] but believed that [[Karl Marx|Marx]]’s theory had come to be interpreted too narrowly. They believed that objective knowledge is not possible because all ideas are produced by the society in which they arise. Horkheimer saw popular culture as a means of manipulation. Adorno believed that [[jazz]] and pop [[music]] distracted people and made them passive. His study on the "authoritarian personality" concluded that prejudice came from rigid, authoritarian homes. Marcuse proclaimed that thought became flattened in the one-dimensional modern society. | |

| − | + | One of the most influential critical theorists, Habermas developed his hermeneutic (understanding) theory, concluding that modern society would come to a point of crisis because it could not meet individuals' needs and because institutions manipulate individuals. He advocated that people respond by "communicative action" ([[communication]]), reviving rational debate on matters of political importance in what he called the "public sphere." | |

| − | + | Contributions to the critical perspective have come from other countries. [[France|French]] sociologists, [[Pierre Bourdieu]] (1930–2002), analyzed society in terms of sometimes autonomous fields (as in academic field), not classes. He introduced the now popular terms social (relationships) and cultural capital, along with economic capital. American theorist [[C. Wright Mills]] (1916–1962) claimed America was ruled by the power elite. It was the sociological imagination that would turn personal problems into public issues and create change. British theorist [[Ralph Dahrendorf]] (1929–) concluded that [[conflict]] is the great creative force of history. When the balance of power shifts, changes happen. Immanuel Wallerstein (1930–) expanded conflict theory to a world level in his World Systems Theory. | |

| − | + | === Post Modern and Post Structural Theory === | |

| + | |||

| + | In the 1970s, a group of theorists developed a critique of contemporary society using [[language]] as a source of evidence for their claims. Like critical theorists, they were critical of [[science]]. Like the neo-Marxists, they were more likely to discuss large scale social trends and structures using theories that were not easily supported or measured. Extreme [[deconstruction]]ists or [[poststructural]]ists may even argue that any type of research method is inherently flawed. | ||

| − | + | The idea of discourse and deconstruction came from [[Jacques Derrida]] (1930—2004). He thought of talking as something that mediates reality. His poststructuralist view was that there is no structure, no cause, only discourse and text. A text can have a range of meanings and interpretations. Questioning the accepted meaning can result in strikingly new interpretations. | |

| − | + | An important postmodern critique came from [[Michel Foucault]] (1926–1984), who analyzed the social institutions of [[psychiatry]], [[medicine]], and [[prison]] as an exemplification of the modern world. He observed shifts of power, and talked about epistimes that define an age. | |

| − | + | [[Postmodern]]ists claim there has been a major shift from modern to postmodern, the latter being characterized as a fragmented and unstable society. [[Globalization]] and [[consumerism]] has contributed to the fragmentation of authority and the commoditization of knowledge. For the postmodernist, experience and meaning are personal, and cannot be generalized, so universal explanations of life are unreal. [[Norm]]s and cultural behavior of the past are being replaced by individualized ideologies, [[myth]]s, and stories. In this view, [[culture]] is as important as [[economics]]. Social theory in this sense becomes less analysis and more social commentary. | |

| − | === | + | === Other Theories === |

| + | |||

| + | Other significant social theories include [[Phenomenology]], developed by [[Edmund Husserl]] (1859–1938). There has been a trend toward [[evolution]]ary theories, from Gerhard Lenski to Anthony Giddens and others. [[Feminism|Feminist theory]] has become a separate focus, as has [[sociobiology]]. | ||

| + | == Future of Social Theory == | ||

| − | + | In the end, social theories are created by people, so they reflect the shortcomings of the theorists. While popular theories are refined by continual use, and hence come to acquire a perspective larger than any single person, it is difficult to develop a single theory comprehensive enough to describe all of the facets of society and the various social relationships. Twenty-first century theorists became more inclined to appreciate theorists in different camps than before, with the result that several different theories may be used in one research project. The major problem with combining of theories is the accompanying baggage associated with each theory, mainly the different assumptions and definitions. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Overall, social theory at the beginning of the twenty-first century became, in some ways, more fragmented than in the past, due in part to changing social morals. This is seen especially in the area of [[family]]—an area with a great deal of research, but little coherent theory to pull it together. | ||

| + | Nevertheless, in an age of [[globalization]], the need for social theory has become increasingly essential. In a shrinking and diverse world, understanding social relations has become paramount. A successful social theory must, therefore, incorporate all aspects of our world, harmonizing the methodologies and insights from a wide range of disciplines. | ||

| + | == Sources == | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Ahmad, Imad A. "An Islamic Perspective on the Wealth of Nations" in [http://www.minaret.org/malaysia.htm ''Minaret of Freedom Institute'']. Bethesda, M.D. | ||

| + | *Allen, Kenneth. 2006. ''Contemporary Social and Sociological Theory''. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. | ||

| + | *Elliott, Anthony & Bryan S. Turner (eds.). 2001. ''Profiles in Contemporary Social Theory''. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. | ||

| + | *Matthews, George. [http://www.angelfire.com/mac/egmatthews/worldinfo/glossary/ibn.html ''Ibn Khaldun'']. Accessed May 26, 2006. | ||

| + | *Turner, Jonathan H. 2003. ''The Structure of Sociological Theory''. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. | ||

| + | *Wallace, Ruth A. & Alison Wolf. 2006. ''Contemporary Sociological Theory''. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. | ||

{{Credit2|Social_theory|42951477|Sociology_versus_social_theory|30772425|}} | {{Credit2|Social_theory|42951477|Sociology_versus_social_theory|30772425|}} | ||

Latest revision as of 15:39, 8 October 2015

| Sociology |

| Subfields |

|---|

|

Comparative sociology ·

Cultural sociology |

| Perspectives |

|

Conflict theory · Critical theory |

| Related Areas |

|

Criminology |

Social theory refers to the use of abstract and often complex theoretical frameworks to describe, explain, and analyze the social world.

A good social theory reveals things that otherwise remain hidden. It also makes predictions about future actions, activity or situations. In general, the appeal of social theory derives from the fact that it takes the focus away from the individual (which is how most humans look at the world) and focuses it on the society itself and the social forces that affect our lives. This sociological insight (often termed the "sociological imagination") looks beyond the assumption that social structures and patterns are purely random, and attempts to provide greater understanding and meaning to human existence. To succeed in this endeavor, social theorists, from time to time, incorporate methodologies and insights from a variety of disciplines.

Introduction

Although many commentators consider social theory a branch of sociology, it has several interdisciplinary facets. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, other areas of the social sciences, such as anthropology, political science, economics, and social work branched out into their own disciplines, while social theory developed and flourished within sociology. Sociological subjects related to understanding society and its development became part of social theory. During this period, social theory by and large reflected traditional views of society, including traditional views of family and marriage.

Attempts at an interdisciplinary discussion free of the restrictions imposed by the more scientifically oriented disciplines began in the late 1920s. The Frankfurt Institute for Social Research provided the most successful example. The Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago followed in the 1940s. In the 1970s, programs in Social and Political Thought were established at Sussex and York College. Others followed, with various different emphases and structures, such as Social Theory and History (University of California, Davis). Cultural Studies programs, notably that of Birmingham University, extended the concerns of social theory into the domain of culture and thus anthropology. A chair and undergraduate program in social theory was established at the University of Melbourne and a number of universities began to specialize in social theory.

Meanwhile, social theory continued to be used within sociology, economics, and related social sciences that had no objections to scientific restrictions.

History

Pre-classical Social Theorists

Prior to the nineteenth century, social theory was largely narrative and normative, expressed in story form, with ethical principles and moral acts. Thus religious figures can be regarded as the earliest social theorists. In China, Master Kong (otherwise known as Confucius or Kung Fu-tzu) (551–479 B.C.E.) envisaged a just society that improved upon the Warring States. Later in China, Mozi (c. 470 – c. 390 B.C.E.) recommended a more pragmatic, but still ethical, sociology. In Greece, philosophers Plato (427–347 B.C.E.) and Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.) were known for their commentaries on social order. In the Christian world, Saint Augustine (354–430) and Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225–1274) concerned themselves exclusively with a just society. St. Augustine, who saw the late Ancient Roman society as corrupt, theorized a contrasting "City of God."

European philosophers also theorized about society and contributed important ideas to the development of social theory. Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) saw the social order as being created by people who have the right to withdraw their consent to a monarchy. John Locke (1632–1704) recognized that people can agree to work together. Baron de Montesquieu (1689–1775) postulated a natural social law that could be observed. Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) believed that people working together can create the laws needed to establish a good society. Edmund Burke (1729–1797) saw society is an organic whole. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) believed that only the rational, moral person, not ruled by passion, can be free. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) described the way in which rationality and morality develop together as people reflect on society.

The early thinkers were concerned with establishing an ideal society, however, not analyzing society as it exists. A notable exception was Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406), a Muslim philosopher and statesman from Egypt and Tunisia. In his book Al Muqaddimah, (or The Introduction to History) he analyzed the policies that led to the rise and fall of dynasties, explaining that in the Arab world the conquering nomads originally settled in the towns. Later, when the invaders lost their desert skills and adopted the vices and slackness of town life, they become ripe for a new group of conquering nomads. His contemporaries ignored his theories, but they found their way into Western commentaries on national wealth.

Hegel was the European philosopher who most influenced modern social analysts. Phenomenology of Spirit (sometimes translated Phenomenology of Mind) is his description of social development through thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. This can be seen at work in a group that has a fixed set of ideas about the world. The more ardently the group presses their ideas, the more likely another group will challenge them. Both groups are likely to be somewhat extreme. Over time, a middle view that incorporates aspects of each group develops and is accepted by society. Thus does a society refine itself and progress towards ever more sophisticated concepts of life and morality.

Classical Social Theory

More elaborate social theories (known as classical theories) were developed by European thinkers after several centuries of drastic social change in Western Europe. The Reformation, Renaissance and the Enlightenment were followed by industrialization, urbanization and democracy. Traditional ways of life were crumbling. The authority of the church, the king, and the upper classes was challenged, families were separated by the migration to the city, and previously self-sufficient farmers became dependent upon others for their daily needs. New means of transportation and communication increased the speed of change, and the individual came to be seen as a person worthy of rights and privileges.

The classical theorists tried to make sense of all of these changes. Their theories are known as “grand theories”—comprehensive views that attempted to explain all of society with a single set of concepts. They usually included the Christian idea of "social progress" and religious elements, although the theorists themselves were not necessarily religious. They also included science and technology, either as a saving grace or something to be feared. Many of the classical theorists had university appointments: Emile Durkheim was the first to have a sociology appointment.

Auguste Comte (1798–1857), considered the "father of sociology," developed the theory of "Human Progress," in which development started with the theological stage in which people attribute the cause of social events to God. In the metaphysical stage people are more realistic, and in the positivistic stage they come to understand life in terms of empirical evidence and science. This theory was popularized by Harriet Martineau (1802–1876), who translated Comte's work into English. A social theorist in her own right, Martineau's theories remained largely unknown for many years.

The theory of social evolution known as social Darwinism was developed by Herbert Spencer (1820–1903). It was Spencer, not Darwin, who coined the famous term "survival of the fittest," which he used to explain social inequalities. His lesser-known theory, the Law of Individuation, contends that each person develops into own separate identity. A fierce advocate of personal freedom and development, Spencer believed that the state ultimately existed to protect the rights of the individual.

Marxism is the theory of social inequality developed by Karl Marx (1818–1883), who claimed he turned Hegel “on its head.” Concerned about the consequences of industrial development, Marx advocated a revolution of the working class to overthrow the ruling capitalists. The political components of his theory inspired a number of revolutions around the world including the Russian Revolution of 1917. Although Marx was a contemporary of Spencer and Comte, his social theory did not become popular until the twentieth century.

The idea of a "collective conscious" (the beliefs and sentiments of a group), reminiscent of Hegel, came from Emile Durkheim, who thought that a person is not truly human without the social. Durkheim viewed norms, the unwritten and unspoken rules of behavior that guide social interaction, as essential to a healthy society. Without them, anomie, or a state of normlessness, when a society is unable to provide guidance results, and persons experiencing anomie feel lost and are susceptible to suicide. “Sacred,” “profane” (not sacred) and “totem” (an external representation of the collective spiritual experience) are significant concepts from his theory of religion. He predicted a future age of individual religion—“the cult of the individual”—when people internalize and revise collective totems for their own inner needs.

In The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Max Weber (1864–1920) predicted that the external pursuit of wealth, even if taken as evidence of God’s approval (as it was for the Calvinists), would become a cage of mundane passions. Weber was also concerned about the effects of rational authority, especially as found in bureaucracy.

Other classical theories include the ideas of Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923) and Pitirim Sorokin, who were skeptical of technology and argued that progress is an illusion. Their social cycle theory illustrated the point that history is really a cycle of ups and downs. Ferdinand Tönnies (1855–1936) focused on "community" and "society," developing the concepts of Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft to describe the contrast between personal, intimate relationships and impersonal, bureaucratic ones.

Modern Social Theory

By and large, the classical theorists were strongly "structural-functional:" they tended to see society as an integrated system of stable social patterns {social structure}. Society was often compared to a living organism, with customs and activities filling different functions or needs.

Early in the twentieth century, social theory began to include free will, individual choice, and subjective reasoning. Instead of classical determinism, human activity was acknowledged to be unpredictable. Thus social theory became more complex. The "symbolic interactionist" perspective of George Herbert Mead (1863–1931) argued that individuals, rather than being determined by their environment, helped shape it. Individual identity and their roles in relationships are a key aspect of this theory.

The "social conflict" perspective, based on Marx’s theory, focused on the unequal distribution of physical resources and social rewards, particularly among groups differentiated by race, gender, class, age, and ethnicity. Since it included studies of prejudice and discrimination, it not surprisingly became a favorite of women and minorities. Conflict theorists believe that those in power created society’s rules for their own benefit and, therefore, that conflict and confrontation may be necessary to bring social change.

These three perspectives became the dominant paradigms within sociology during the twentieth century. Each paradigm represents an historical development and new areas of exploration about society. Generally, theorists have advocated one perspective over the others.

Later Developments

The latter part of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century saw the emergence of several new types of social theory, building on previous approaches but incorporating new ideas both from within sociology and the social sciences, but also from more distant fields in the physical and life sciences, as well as incorporating new philosophical orientations.

Systems Theory

Systems theory is one of the theoretical trends that developed in the late twentieth century that is truly interdisciplinary. In general, it is structural, but always holistic—a system cannot be understood by understanding the parts. Interaction and relationships are essential to a complete understanding of a social system. Systems theories are not reductionist, and they tend toward non-linearity and indeterminacy. In these ways they reject traditional scientific concepts, although most systems theorists still subscribe to time honored scientific methods.

Talcott Parsons’ (1902–1979) systems theory dominated sociology from 1940 to 1970. It was a grand systems theory, wherein each system was composed of actors, goals and values, boundaries and patterns of interaction. His theory included the idea of human agency. A co-author of Parson's "Toward a General Theory of Action" was Edward Shils (1911–1995), who subsequently became concerned about the dumbing down, politicization and compromises within the intellectual life. For Shils, a civil society is an important mediator between the state and the individual.

The biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1901–1972), whose General Systems Theory appeared almost simultaneously with Parson’s theory, believed his theory would be a new paradigm to guide model construction in all the sciences. He sought to capture the dynamic life processes in theoretical terms, using concepts such as open systems, equilibrium, system maintenance, and hierarchical organization. His theory gained wide recognition in both the physical and social sciences and is often associated with cybernetics, a mathematical theory of communication and regulatory feedback developed by W. Ross Ashby and Norbert Wiener in the 1940s and 1950s.

The Living Systems Theory developed by James Grier Miller (1916–2002) focused on characteristics unique to living systems—open, self-organizing systems that interact with their environment. Walter Buckley (1921–2005) focused on psychological and sociocultural systems, drawing distinctions between the simple mechanical systems of physical science with no feedback loops, and the complex adaptive systems that have feedback loops, are self regulatory, and exchange information and energy with the environment.

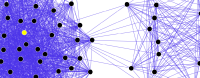

Network theory grew out of the studies of British anthropologists (Elizabeth Bott and others) in the 1950s, using Moreno’s sociometry and other graphic models from social psychology, as well as cybernetics and mathematical concepts, to chart relationship patterns. Network theory appeals especially to macrotheorists who are interested in community and nation power structures. Related to network is exchange theory&madash;a theory that started as a behavioralistic theory with George C. Homans (1910-1989) and expanded to include power, equity, and justice (Richard Emerson, Karen Cook), as well as the sources of strain and conflict in micro and macro situations (Peter Blau).

Niklas Luhmann (1927-1998) used systems to describe society, but his approach is less deterministic than the theories above. He envisioned a self-organizing, living system with no central coordination. Such a system is created by the choices that people make, and trust and risk are key components.

In the 1970s, René Thom introduced the idea of bifurcation—a state of system overload created by multiple feedback channels—through his development of catastrophe theory. In this situation, a deterministic system can generate two or more solutions. Non-linear phenomena were further examined in the 1980s in chaos theory. Developed by theorists from a range of disciplines—mathematics, technology, biology, and philosophy—chaos theory spread to all academic disciplines. Complexity theory that followed was a return to more deterministic principles. With the idea of emergence, or system choice, the line between living and non-living things became blurred.

Neo Marxism

Critical theory came from members of the Frankfurt School (Theodore Adorno (1903–1969), Max Horkheimer (1895–1973), Herbert Marcuse (1898–1979), Eric Fromm (1900–1980), Jurgen Habermas (1929–) and others). They began their work in the 1920s but it did not become well-known until the 1960s. They were severe critics of capitalism but believed that Marx’s theory had come to be interpreted too narrowly. They believed that objective knowledge is not possible because all ideas are produced by the society in which they arise. Horkheimer saw popular culture as a means of manipulation. Adorno believed that jazz and pop music distracted people and made them passive. His study on the "authoritarian personality" concluded that prejudice came from rigid, authoritarian homes. Marcuse proclaimed that thought became flattened in the one-dimensional modern society.

One of the most influential critical theorists, Habermas developed his hermeneutic (understanding) theory, concluding that modern society would come to a point of crisis because it could not meet individuals' needs and because institutions manipulate individuals. He advocated that people respond by "communicative action" (communication), reviving rational debate on matters of political importance in what he called the "public sphere."

Contributions to the critical perspective have come from other countries. French sociologists, Pierre Bourdieu (1930–2002), analyzed society in terms of sometimes autonomous fields (as in academic field), not classes. He introduced the now popular terms social (relationships) and cultural capital, along with economic capital. American theorist C. Wright Mills (1916–1962) claimed America was ruled by the power elite. It was the sociological imagination that would turn personal problems into public issues and create change. British theorist Ralph Dahrendorf (1929–) concluded that conflict is the great creative force of history. When the balance of power shifts, changes happen. Immanuel Wallerstein (1930–) expanded conflict theory to a world level in his World Systems Theory.

Post Modern and Post Structural Theory

In the 1970s, a group of theorists developed a critique of contemporary society using language as a source of evidence for their claims. Like critical theorists, they were critical of science. Like the neo-Marxists, they were more likely to discuss large scale social trends and structures using theories that were not easily supported or measured. Extreme deconstructionists or poststructuralists may even argue that any type of research method is inherently flawed.

The idea of discourse and deconstruction came from Jacques Derrida (1930—2004). He thought of talking as something that mediates reality. His poststructuralist view was that there is no structure, no cause, only discourse and text. A text can have a range of meanings and interpretations. Questioning the accepted meaning can result in strikingly new interpretations.

An important postmodern critique came from Michel Foucault (1926–1984), who analyzed the social institutions of psychiatry, medicine, and prison as an exemplification of the modern world. He observed shifts of power, and talked about epistimes that define an age.

Postmodernists claim there has been a major shift from modern to postmodern, the latter being characterized as a fragmented and unstable society. Globalization and consumerism has contributed to the fragmentation of authority and the commoditization of knowledge. For the postmodernist, experience and meaning are personal, and cannot be generalized, so universal explanations of life are unreal. Norms and cultural behavior of the past are being replaced by individualized ideologies, myths, and stories. In this view, culture is as important as economics. Social theory in this sense becomes less analysis and more social commentary.

Other Theories

Other significant social theories include Phenomenology, developed by Edmund Husserl (1859–1938). There has been a trend toward evolutionary theories, from Gerhard Lenski to Anthony Giddens and others. Feminist theory has become a separate focus, as has sociobiology.

Future of Social Theory

In the end, social theories are created by people, so they reflect the shortcomings of the theorists. While popular theories are refined by continual use, and hence come to acquire a perspective larger than any single person, it is difficult to develop a single theory comprehensive enough to describe all of the facets of society and the various social relationships. Twenty-first century theorists became more inclined to appreciate theorists in different camps than before, with the result that several different theories may be used in one research project. The major problem with combining of theories is the accompanying baggage associated with each theory, mainly the different assumptions and definitions.

Overall, social theory at the beginning of the twenty-first century became, in some ways, more fragmented than in the past, due in part to changing social morals. This is seen especially in the area of family—an area with a great deal of research, but little coherent theory to pull it together.

Nevertheless, in an age of globalization, the need for social theory has become increasingly essential. In a shrinking and diverse world, understanding social relations has become paramount. A successful social theory must, therefore, incorporate all aspects of our world, harmonizing the methodologies and insights from a wide range of disciplines.

Sources

- Ahmad, Imad A. "An Islamic Perspective on the Wealth of Nations" in Minaret of Freedom Institute. Bethesda, M.D.

- Allen, Kenneth. 2006. Contemporary Social and Sociological Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

- Elliott, Anthony & Bryan S. Turner (eds.). 2001. Profiles in Contemporary Social Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Matthews, George. Ibn Khaldun. Accessed May 26, 2006.

- Turner, Jonathan H. 2003. The Structure of Sociological Theory. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Wallace, Ruth A. & Alison Wolf. 2006. Contemporary Sociological Theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.