Difference between revisions of "Conscience" - New World Encyclopedia

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) (import from wiki) |

|||

| (69 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Edboard}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}} |

| − | [[ | + | [[File:Vincent Willem van Gogh 022.jpg|thumb|300px|''The good Samaritan'' (after Delacroix) by [[Vincent van Gogh]]]] |

| − | ''' | + | The '''conscience''' refers to a person’s sense of right and wrong. Having a conscience involves being aware of the [[moral]] rightness or wrongness of one’s actions, or the [[goodness]] or badness of one’s intentions. In a [[Christian]] context, conscience is often conceived as a faculty by which [[God]]’s moral laws are known to human beings. Being ‘judged’ by one’s conscience can lead to [[guilt]] and other ‘punitive’ [[emotion]]s. |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | ==The elements of conscience== | ||

| + | Conscience refers to a person’s sense of right and wrong. Having a conscience involves being aware of the moral rightness or wrongness of one’s actions, or the goodness or badness of one’s intentions. In philosophical, religious, and everyday senses, the notion of conscience may include the following separable elements. | ||

| − | + | Firstly, conscience may refer to the moral principles and values that a person endorses. In this sense, one can be said to go against conscience, where this means going against one’s basic moral convictions. | |

| − | + | Secondly, conscience may refer to a faculty whereby human beings come to know basic moral truths. This faculty has been described variously as “the voice of God,” “the voice of reason,” or as a special “moral sense.” For example, in Romans 2: 14-15, [[Saint Paul]] describes conscience as “bearing witness” to the law of God “inscribed” on the hearts of Gentiles. This conception of conscience, as a faculty by which God’s moral laws are known to human beings, is continued in the writings of the Church fathers such as [[Saint Jerome]] and [[Saint Augustine]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | A third aspect closely associated with conscience pertains to self-scrutiny: conscience involves a person’s examination of his or her own desires, and actions, and connects with sentiments of self-evaluation, such as [[guilt]], [[shame]], [[regret]] and [[remorse]]. This aspect of conscience is encapsulated in the expression “pangs of conscience,” which designates the painful experience of being found morally wanting by the lights of one’s own self-scrutiny. Living with painful emotions such as guilt and shame are elements in a “bad conscience.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The role of [[emotion]]s such as guilt in a functioning conscience is not subsidiary to rational evaluation. On occasion, one may become aware of having done something wrong by experiencing the emotions of self-assessment—these may be indicators that something is morally amiss—even before one knows what this is. It is also important that acts of self-scrutiny need not come about by will, that is, though decisions to morally evaluate oneself; in one of the most important modern discussions of the moral significance of conscience, [[Joseph Butler]] put this point elegantly, writing that conscience “magisterially exerts itself without being consulted, [and] without being advised with…”<ref name=Butler>Joseph Butler, ''Five Sermons Preached at the Rolls Chapel and A Dissertation Upon the Nature of Virtue'', ed. S. Darwall, (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Pub. Co., 1983, ISBN 978-0915145614).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | == Religious views of conscience == | |

| − | + | According to some religious perspectives, your conscience is what bothers you when you do evil to your neighbor, or which informs you of the right or wrong of an action before committing it. Doing good to your neighbor doesn't arouse the conscience to speak, but wickedness inflicted upon the innocent is sure to make the conscience scream. This is because in this world view, God has commanded all men to love their neighbor. Insofar as a man fails to do this, he breaks God's law and thus his conscience bothers him until he confesses his sin to God and repents of that sin, clearing his conscience. If one persists in an evil way of life for a long period of time, it is referred to as having one's conscience seared with a hot iron. A lying hypocrite is an example of someone who has ignored their conscience for so long that it fails to function. | |

| − | + | Many [[church]]es consider following one's conscience to be as important as, or even more important than, obeying human [[authority]]. This can sometimes lead to moral quandaries. "Do I obey my church/military/political leader, or do I follow my own sense of right and wrong?" Most churches and religious groups hold the moral teachings of their sacred texts as the highest authority in any situation. This dilemma is akin to [[Antigone]]'s defiance of King Creon's order, appealing to the "[[natural law|unwritten law]]" and to a "longer allegiance to the dead than to the living"; it can also be compared to the trial of Nazi war criminal [[Adolf Eichmann]], in which he claimed that he had followed [[Kant]]ian philosophy by simply "doing his job" instead of entering a state of [[civil disobedience]].<ref>Hannah Arendt, ''Eichmann in Jerusalem : A Report on the Banality of Evil'' (Penguin Books, 1977).</ref> | |

| − | + | In popular culture, the conscience is often illustrated as two entities, an angel and a devil, each taking one shoulder. The angel often stands on the right, the good side; and the devil on the left, the [[sinister]] side (left implying bad luck in [[superstition]], and the word sinister coming from the [[Latin]] word for left). These entities will then 'speak out' to you and try to influence you to make a good choice or bad choice depending on the situation. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | === | + | === Christian views === |

| − | + | The following Biblical references are often cited regarding conscience: | |

| − | + | * {{bibleverse|1|Timothy|4:1,2}}: "Now the Spirit speaks expressly, that in the latter times some shall depart from the faith, giving heed to seducing spirits, and doctrines of devils speaking lies in hypocrisy; having their conscience seared with a hot iron." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * {{bibleverse|1|Timothy|4:1,2}}: "Now the Spirit speaks expressly, that in the latter times some shall depart from the faith, giving heed to seducing spirits, and doctrines of devils speaking lies in hypocrisy; having their conscience seared with a hot iron" | ||

* {{bibleverse||Romans|2:14-15}}: " When Gentiles who do not possess the law carry out its precepts by the light of nature, then, although they have no law, they are their own law; they show that what the law requires is inscribed on their hearts, and to this theur conscience gives supporting witness, since their own thoughts argue the case, sometimes against them, sometimes even for them." | * {{bibleverse||Romans|2:14-15}}: " When Gentiles who do not possess the law carry out its precepts by the light of nature, then, although they have no law, they are their own law; they show that what the law requires is inscribed on their hearts, and to this theur conscience gives supporting witness, since their own thoughts argue the case, sometimes against them, sometimes even for them." | ||

| − | ==== | + | ==== Catholic theology ==== |

| − | Conscience, in Catholic theology, is "a judgment of reason whereby the human person recognizes the moral quality of a concrete act he is going to perform, is in the process of performing, or has already completed" | + | Conscience, in Catholic theology, is "a judgment of reason whereby the human person recognizes the moral quality of a concrete act he is going to perform, is in the process of performing, or has already completed."<ref>[http://www.scborromeo.org/ccc/para/1778.htm Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 1778]. Retrieved March 21, 2023.</ref> Catholics are called to examine their conscience before [[confession]]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Obedience to conscience has been claimed by many dissenters as a God-given right, from [[Martin Luther]], who said (or reputedly said), "Here I stand, I can do no other," to progressive Catholics who disagree with certain [[doctrine]]s or [[dogma]]s. The Church eventually agreed, saying, "Man has the right to act according to his conscience and in freedom so as personally to make moral decisions. He must not be forced to act contrary to his conscience. Nor must he be prevented from acting according to his conscience, especially in religious matters."<ref>[http://www.scborromeo.org/ccc/para/1782.htm Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 1782]. Retrieved March 21, 2023.</ref> In certain situations involving individual personal decisions that are incompatible with church law, some pastors rely on the use of the [[internal forum]] solution. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | However, the Catholic Church has warned that "rejection of the Church's authority and her teaching...can be at the source of errors in judgment in moral conduct."<ref>[http://www.scborromeo.org/ccc/para/1792.htm Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 1792]. Retrieved March 21, 2023.</ref> | |

| − | ==== | + | ==== Protestant theology ==== |

| − | The | + | The [[Reformation]] began with [[Luther]]'s crisis of conscience. And for many [[Protestant]]s, following one's consciences could rank higher than obedience to church authorities or accepted interpretations of the [[Bible]]. One example of a Protestant theologian who caused his church to rethink the issue of conscience was [[William Robertson Smith]] of the [[Free Church of Scotland (1843-1900)|Free Church of Scotland]]. Tried for heresy because of his use of modern methods of interpreting the [[Old Testament]], he received only a token punishment. However the case contributed to a situation in which many Protestant denominations allow a wide variety of beliefs and practices to be held by their members in accordance with their conscience. |

| − | + | ===World Religions=== | |

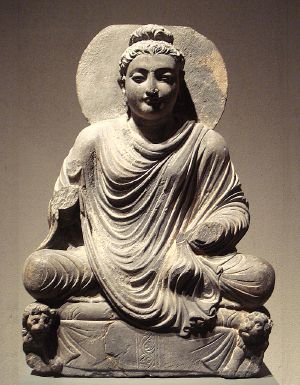

| + | [[File:SeatedBuddhaGandhara2ndCenturyOstasiatischeMuseum.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Seated [[Buddha]], [[Gandhara]], 2nd century CE. The Buddha linked conscience with compassion for those who must endure cravings and suffering in the world until right conduct culminates in right mindfulness and right contemplation.]] | ||

| − | + | In the literary traditions of the [[Upanishads]], [[Brahma Sutras]] and the [[Bhagavad Gita]], conscience is the label given to attributes composing knowledge about good and evil, that a [[Soul (spirit)|soul]] acquires from the completion of acts and consequent accretion of [[karma]] over many lifetimes.<ref>Ninian Smart, ''The World's Religions'' (Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0521637480).</ref> According to [[Adi Shankara]] in his ''[[Vivekachudamani]]'' morally right action (characterized as humbly and compassionately performing the primary duty of good to others without expectation of material or spiritual reward), helps "purify the heart" and provide mental tranquility but it alone does not give us "direct perception of the Reality."<ref name=Shankara>Shankara, ''Crest-Jewel of Discrimination'', trans. Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isherwood, (Vedanta Press, 1970, ISBN 978-0874810387).</ref> This knowledge requires discrimination between the eternal and non-eternal and eventually a realization in [[contemplation]] that the true self merges in a universe of pure consciousness.<ref name=Shankara/> | |

| − | + | In the [[Zoroastrian]] faith, after death a soul must face judgment at the ''Bridge of the Separator''; there, [[evil]] people are tormented by prior denial of their own higher nature, or conscience, and "to all time will they be guests for the ''House of the Lie''."<ref name=Noss>John B. Noss, ''Man's Religions'' (Macmillan Publishing Co., 1972, ISBN 978-0023884405).</ref> The [[China|Chinese]] concept of [[Ren (Confucianism)|Ren]], indicates that conscience, along with social etiquette and correct relationships, assist humans to follow ''The Way'' ([[Tao]]) a mode of life reflecting the implicit human capacity for goodness and harmony.<ref>Antonia S. Cua, ''Moral Vision and Tradition: Essays in Chinese Ethics'' (Catholic University of America Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0813208909).</ref> | |

| − | + | Conscience also features prominently in [[Buddhism]].<ref>Jayne Hoose (ed.), ''Conscience in World Religions'' (University of Notre Dame Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0852443989).</ref> In the [[Pali]] scriptures, for example, [[Buddha]] links the positive aspect of ''conscience'' to a pure heart and a calm, well-directed mind. It is regarded as a spiritual power, and one of the “Guardians of the World”. The Buddha also associated conscience with compassion for those who must endure cravings and suffering in the world until right conduct culminates in right mindfulness and right [[contemplation]].<ref>Ninian Smart, ''The Religious Experience of Mankind'' (Charles Scribner's Sons, 1969, ISBN 978-0684414348).</ref> [[Santideva]] (685–763 C.E.) wrote in the [[Bodhicaryavatara]] (which he composed and delivered in the great northern Indian Buddhist university of [[Nalanda]]) of the spiritual importance of perfecting virtues such as [[generosity]], [[forbearance]] and training the awareness to be like a "block of wood" when attracted by vices such as [[pride]] or [[lust]]; so one can continue advancing towards right understanding in meditative absorption.<ref>Santideva, ''The Bodhicaryavatara'', trans. Andrew Skilton and Kate Crosby, (Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0199540433).</ref> ''Conscience'' thus manifests in Buddhism as unselfish love for all living beings which gradually intensifies and awakens to a purer awareness where the mind withdraws from sensory interests and becomes aware of itself as a single whole. | |

| − | + | [[File:Bronze Marcus Aurelius Louvre Br45.jpg|thumb|300px|[[Marcus Aurelius]] bronze fragment, Louvre, Paris: "To move from one unselfish action to another with God in mind. Only there, delight and stillness."]] | |

| + | The [[Roman Emperor]] [[Marcus Aurelius]] wrote in his ''[[Meditations]]'' that conscience was the human capacity to live by rational principles that were congruent with the true, tranquil and harmonious nature of our mind and thereby that of the Universe: "To move from one unselfish action to another with God in mind. Only there, delight and stillness ... the only rewards of our existence here are an unstained character and unselfish acts."<ref>Marcus Aurelius, ''Meditations'' Gregory Hays (trans.), (Black and White Classics, 2014, ISBN 978-1503280465).</ref> | ||

| − | + | The [[Islamic]] concept of ''[[Taqwa]]'' is closely related to conscience. In the [[Qur’ān]] verses 2:197 and 22:37, Taqwa refers to "right conduct" or "[[piety]]," "guarding of oneself" or "guarding against evil."<ref>Sachiko Murata and William C. Chittick, ''The Vision of Islam'' (I.B. Tauris, 2006, ISBN 978-1557785169).</ref> [[Qur’an]] verse 47:17 says that God is the ultimate source of the believer's taqwā which is not simply the product of individual will but requires inspiration from God. In [[Qur’ān]] verses 91:7–8, God the Almighty talks about how He has perfected the soul, the conscience and has taught it the wrong (fujūr) and right (taqwā). Hence, the awareness of vice and virtue is inherent in the soul, allowing it to be tested fairly in the life of this world and tried, held accountable on the day of judgment for responsibilities to God and all humans.<ref>Azim Nanji, "Islamic Ethics" in Peter Singer (ed.), ''A Companion to Ethics'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 1993, ISBN 978-0631187851).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Qur’ān]] verse 49:13 states: "O humankind! We have created you out of male and female and constituted you into different groups and societies, so that you may come to know each other-the noblest of you, in the sight of God, are the ones possessing taqwā." In [[Islam]], according to eminent theologians such as [[Al-Ghazali]], although events are ordained (and written by God in al-Lawh al-Mahfūz, the ''Preserved Tablet''), humans possess free will to choose between wrong and right, and are thus responsible for their actions; the conscience being a dynamic personal connection to God enhanced by knowledge and practice of the [[Five Pillars of Islam]], deeds of piety, repentance, self-discipline, and prayer; and disintegrated and metaphorically covered in blackness through sinful acts.<ref name=Noss/><ref>Marshall G.S. Hodgson, ''The Venture of Islam, Volume 1: The Classical Age of Islam'' (University of Chicago Press, 1977, ISBN 978-0226346830).</ref> | |

| − | + | ==Philosophical conceptions== | |

| − | + | ===The Church Fathers=== | |

| − | + | The notion of conscience ([[Latin]]: conscientia) in not found in ancient Greek ethical writings. However, Platonic and Aristotelian conceptions of the soul as possessing a reasoning faculty, which is responsible for choosing the correct course of action (Greek: orthos logos = right reason) were important antecedents to the conception of conscience developed in the patristic period of Christianity. Following on from the writings of [[Saint Paul]], early Christian philosophers were concerned with the question of how pagans, who had not come to know the revealed truth of God, could justly be deprived of the means to salvation. Their response was to claim that all human beings possess a natural moral faculty—conscience—so that pagans could also come to know God’s moral laws (also revealed through revelation), and hence live morally good lives. In this respect, [[Saint Jerome]] introduced the notion of synderesis (or synteresis) to refer to a moral faculty whereby we “discern that we sin,” describing synderesis as a “spark of conscience, which was not even extinguished in the breast of Cain after he was turned out of paradise…” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Saint Thomas Aquinas=== |

| + | Probably because of a misinterpretation of [[Saint Jerome]], medieval philosophers supported a sharp distinction between synderesis and conscience. [[Thomas Aquinas]], for example, argues that the most basic principle of human conduct—that good is to be pursued and evil to be avoided—is known by the faculty of synderesis. However this basic principle is too general to help one know how to act in particular circumstances. Even if one aims to choose good, and aims to refrain from bad, this still leaves the question of which actions are good and which ones are bad in the situation. On Aquinas’ model, conscience is conceived as filling this gap. Conscience is a capacity that enables man to derive more specific principles (e.g. thou shall not kill), and also to apply these principles to a given circumstance. Even though the synderesis rule (“Do good and eschew evil”) is held to be infallible, errors in conscience are possible because one may make mistakes in deriving specific rules of conduct, or alternatively, make mistakes in applying these rules to the situation. | ||

| − | + | In ''Summa Theologica'' Thomas Aquinas discusses the moral problem of the “erring conscience.” Given that Aquinas conceives of the synderesis rule (“Do good and eschew evil”) as self-evident, an erring conscience refers either to a mistaken set of basic moral principles and values, or an inability to know which principles apply in the particular case. The moral problem of the erring conscience is that one does wrong in doing what is objectively bad. However, one also does wrong in going against conscience, that is, in doing what one believes to be bad. So, either way, the person with a distorted conscience does wrong: “unless he put away his error [he] cannot act well.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Joseph Butler=== |

| − | [[ | + | One of the most sophisticated modern discussions of conscience is found in the writings of [[Joseph Butler]]. Butler analyzes man’s nature into a hierarchy of motivations: there are, first, the particular passions such as a hunger, thirst, and other bodily needs, compassion, love, and hate; secondly, there are there are the principles of benevolence and self-love; roughly speaking, benevolence is a desire for the happiness of others, whereas self-love is a desire for one’s own happiness. The third and most important part of Butler’s analysis of human nature is conscience, which he claims to be essential to man’s being a moral agent.<ref name=Butler/> Butler conceives of conscience as a principle of reflection that “judges acts right or wrong and characters and motives virtuous or vicious.” He also describes conscience as a “sentiment of the understanding” and “a perception of the heart.” |

| − | + | On Butler’s analysis a virtuous person is someone who has all his parts functioning in a proper hierarchy. This means that particular passions are controlled by the self-love and benevolence, and these (and the particular passions) are in turn controlled by conscience. According to Butler, then, conscience rules supreme in the virtuous person. | |

| − | + | ===Friedrich Nietzsche=== | |

| + | Christian thinkers have tended to focus on conscience’s fundamental importance as a moral guide. [[Nietzsche]], by contrast, focuses attention on what happens when conscience becomes unhealthy, that is, the notion of “bad conscience.” Nietzsche’s discussion of conscience is part of his account of the genealogy of morality, and the attendant notion of guilt. Nietzsche conceives of “bad conscience” as involving a sense of guilt and unworthiness, which comes about when one’s aggressive impulses fail to be expressed externally, so that they are suppressed and are turned inwards, directed against the self. Nietzsche’s solution to the problem of “bad conscience” involves a rejection of the morality system, which he regards as “life-denying,” and the presentation of an alternative “life-affirming” set of values. | ||

| − | + | ===Sigmund Freud=== | |

| + | The “self-punitive” strand in conscience, criticized by Nietzsche, has also been discussed by [[Sigmund Freud]]. On Freud’s conceptual model, the human person is divided into [[id, ego, and superego]]. The primitive ‘it’, or id, is a natural repository of basic instincts, which Freud divides into life (eros) and death (thanatos) drives. Life drives are concerned with affection, and love, while death drives yield motives such as envy and hate. The ego (“das Ich”—German: “the I”) and super-ego develop out of the id. On Freud’s analysis, conscience is identified with super-ego, which is an internalization of the moral authority of parental figures (particularly the father). [[Guilt]] arises from the super-ego in response to aggressive or sexual impulses arising from the id, which are subject to the moral evaluation of the internalized moral authority. Conscience, or super-ego, is much more severe than a person’s actual parents; it can be a source of substantial anxiety and guilt, and sometimes, in severe cases, of [[suicide]]. | ||

| − | + | == Notes == | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | * | + | *Aquinas, Thomas. ''Summa theologiae'' (Synopsis of Theology), ed. T. Gilby. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1970, vol. 11, Ia.79.11-13; 1966, vol. 18, IaIIae.19.5-8. |

| − | * | + | *Arendt, Hannah. ''Eichmann in Jerusalem : A Report on the Banality of Evil''. Penguin Classics, 2006 (original 1977). ISBN 978-0143039884 |

| − | * | + | *Aurelius, Marcus, Gregory Hays (trans.). ''Meditations''. Black and White Classics, 2014. ISBN 978-1503280465 |

| − | * | + | *Butler, Joseph. ''Five Sermons Preached at the Rolls Chapel and A Dissertation Upon the Nature of Virtue'', ed. S. Darwall. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Pub. Co., 1983. ISBN 978-0915145614 |

| − | * | + | *Cua, Antonia S. ''Moral Vision and Tradition: Essays in Chinese Ethics''. Catholic University of America Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0813208909 |

| − | * | + | *Davies, Brian. ''The Thought of Thomas Aquinas''. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992. ISBN 9780198267539 |

| − | * | + | *Dolan, Joseph V. "Conscience in the Catholic Theological Tradition." In ''Conscience: Its Freedom and Limitations'', William C. Bier (editor). Fordham University Press, 1971. ISBN 0823209059 |

| − | * | + | *Freud, Sigmund. ''The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud''. London: Hogarth Press, 1955. ISBN 0876681356 |

| − | * | + | *Hodgson, Marshall G.S. ''The Venture of Islam, Volume 1: The Classical Age of Islam''. University of Chicago Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0226346830 |

| − | * | + | *Hoose, Jayne (ed.). ''Conscience in World Religions''. University of Notre Dame Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0852443989 |

| − | * | + | *Langston, Douglas C. ''Conscience and Other Virtues. From Bonaventure to MacIntyre''. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001. ISBN 0271020709 |

| − | * | + | * Murata, Sachiko, and William C. Chittick. ''The Vision of Islam''. I.B. Tauris, 2006. ISBN 978-1557785169 |

| − | * | + | *Nietzsche, Friedrich. ''On the Genealogy of Morality''. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company, 1998. ISBN 978-0872202832 |

| − | * | + | *Noss, John B. ''Man's Religions''. Macmillan Publishing Co., 1972. ISBN 978-0023884405 |

| + | *Potts, Timothy C. ''Conscience in Medieval Philosophy''. Cambridge University Press, 1980. ISBN 0521232872 | ||

| + | *Santideva, trans. Andrew Skilton and Kate Crosby. ''The Bodhicaryavatara''. Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0199540433 | ||

| + | *Shankara, trans. Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isherwood. ''Crest-Jewel of Discrimination''. Vedanta Press, 1970. ISBN 978-0874810387 | ||

| + | *Singer, Peter (ed.). ''A Companion to Ethics''. Wiley-Blackwell, 1993. ISBN 978-0631187851 | ||

| + | *Smart, Ninian. ''The Religious Experience of Mankind''. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1969. ISBN 978-0684414348 | ||

| + | *Smart, Ninian. ''The World's Religions''. Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0521637480 | ||

| + | *Zachman, Randall C. ''The Assurance of Faith. Conscience in the Theology of Martin Luther and John Calvin''. Augsburg Fortress Press, Minneapolis, 1993. ISBN 0800625749 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved March 21, 2023. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * [http://quotes.liberty-tree.ca/quotes/conscience Quotations about Conscience] at ''Liberty-tree.ca''. | |

| − | [ | + | * [https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/conscience/ Conscience] ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' |

| − | [ | + | * [https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/conscience-medieval/ Medieval Theories of Conscience] ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ===General Philosophy Sources=== | ||

| + | *[https://plato.stanford.edu Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy] | ||

| + | *[https://iep.utm.edu/ The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy] | ||

| + | *[https://www.bu.edu/wcp/PaidArch.html Paideia Project Online] | ||

| + | *[https://www.gutenberg.org/ Project Gutenberg] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[category:Philosophy and religion]] | ||

| + | [[Category:philosophy]] | ||

| + | {{Philosophy navigation}} | ||

{{credit|142061576}} | {{credit|142061576}} | ||

Latest revision as of 21:26, 7 September 2023

The conscience refers to a person’s sense of right and wrong. Having a conscience involves being aware of the moral rightness or wrongness of one’s actions, or the goodness or badness of one’s intentions. In a Christian context, conscience is often conceived as a faculty by which God’s moral laws are known to human beings. Being ‘judged’ by one’s conscience can lead to guilt and other ‘punitive’ emotions.

The elements of conscience

Conscience refers to a person’s sense of right and wrong. Having a conscience involves being aware of the moral rightness or wrongness of one’s actions, or the goodness or badness of one’s intentions. In philosophical, religious, and everyday senses, the notion of conscience may include the following separable elements.

Firstly, conscience may refer to the moral principles and values that a person endorses. In this sense, one can be said to go against conscience, where this means going against one’s basic moral convictions.

Secondly, conscience may refer to a faculty whereby human beings come to know basic moral truths. This faculty has been described variously as “the voice of God,” “the voice of reason,” or as a special “moral sense.” For example, in Romans 2: 14-15, Saint Paul describes conscience as “bearing witness” to the law of God “inscribed” on the hearts of Gentiles. This conception of conscience, as a faculty by which God’s moral laws are known to human beings, is continued in the writings of the Church fathers such as Saint Jerome and Saint Augustine.

A third aspect closely associated with conscience pertains to self-scrutiny: conscience involves a person’s examination of his or her own desires, and actions, and connects with sentiments of self-evaluation, such as guilt, shame, regret and remorse. This aspect of conscience is encapsulated in the expression “pangs of conscience,” which designates the painful experience of being found morally wanting by the lights of one’s own self-scrutiny. Living with painful emotions such as guilt and shame are elements in a “bad conscience.”

The role of emotions such as guilt in a functioning conscience is not subsidiary to rational evaluation. On occasion, one may become aware of having done something wrong by experiencing the emotions of self-assessment—these may be indicators that something is morally amiss—even before one knows what this is. It is also important that acts of self-scrutiny need not come about by will, that is, though decisions to morally evaluate oneself; in one of the most important modern discussions of the moral significance of conscience, Joseph Butler put this point elegantly, writing that conscience “magisterially exerts itself without being consulted, [and] without being advised with…”[1]

Religious views of conscience

According to some religious perspectives, your conscience is what bothers you when you do evil to your neighbor, or which informs you of the right or wrong of an action before committing it. Doing good to your neighbor doesn't arouse the conscience to speak, but wickedness inflicted upon the innocent is sure to make the conscience scream. This is because in this world view, God has commanded all men to love their neighbor. Insofar as a man fails to do this, he breaks God's law and thus his conscience bothers him until he confesses his sin to God and repents of that sin, clearing his conscience. If one persists in an evil way of life for a long period of time, it is referred to as having one's conscience seared with a hot iron. A lying hypocrite is an example of someone who has ignored their conscience for so long that it fails to function.

Many churches consider following one's conscience to be as important as, or even more important than, obeying human authority. This can sometimes lead to moral quandaries. "Do I obey my church/military/political leader, or do I follow my own sense of right and wrong?" Most churches and religious groups hold the moral teachings of their sacred texts as the highest authority in any situation. This dilemma is akin to Antigone's defiance of King Creon's order, appealing to the "unwritten law" and to a "longer allegiance to the dead than to the living"; it can also be compared to the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, in which he claimed that he had followed Kantian philosophy by simply "doing his job" instead of entering a state of civil disobedience.[2]

In popular culture, the conscience is often illustrated as two entities, an angel and a devil, each taking one shoulder. The angel often stands on the right, the good side; and the devil on the left, the sinister side (left implying bad luck in superstition, and the word sinister coming from the Latin word for left). These entities will then 'speak out' to you and try to influence you to make a good choice or bad choice depending on the situation.

Christian views

The following Biblical references are often cited regarding conscience:

- 1 Timothy 4:1,2: "Now the Spirit speaks expressly, that in the latter times some shall depart from the faith, giving heed to seducing spirits, and doctrines of devils speaking lies in hypocrisy; having their conscience seared with a hot iron."

- Romans 2:14-15: " When Gentiles who do not possess the law carry out its precepts by the light of nature, then, although they have no law, they are their own law; they show that what the law requires is inscribed on their hearts, and to this theur conscience gives supporting witness, since their own thoughts argue the case, sometimes against them, sometimes even for them."

Catholic theology

Conscience, in Catholic theology, is "a judgment of reason whereby the human person recognizes the moral quality of a concrete act he is going to perform, is in the process of performing, or has already completed."[3] Catholics are called to examine their conscience before confession.

Obedience to conscience has been claimed by many dissenters as a God-given right, from Martin Luther, who said (or reputedly said), "Here I stand, I can do no other," to progressive Catholics who disagree with certain doctrines or dogmas. The Church eventually agreed, saying, "Man has the right to act according to his conscience and in freedom so as personally to make moral decisions. He must not be forced to act contrary to his conscience. Nor must he be prevented from acting according to his conscience, especially in religious matters."[4] In certain situations involving individual personal decisions that are incompatible with church law, some pastors rely on the use of the internal forum solution.

However, the Catholic Church has warned that "rejection of the Church's authority and her teaching...can be at the source of errors in judgment in moral conduct."[5]

Protestant theology

The Reformation began with Luther's crisis of conscience. And for many Protestants, following one's consciences could rank higher than obedience to church authorities or accepted interpretations of the Bible. One example of a Protestant theologian who caused his church to rethink the issue of conscience was William Robertson Smith of the Free Church of Scotland. Tried for heresy because of his use of modern methods of interpreting the Old Testament, he received only a token punishment. However the case contributed to a situation in which many Protestant denominations allow a wide variety of beliefs and practices to be held by their members in accordance with their conscience.

World Religions

In the literary traditions of the Upanishads, Brahma Sutras and the Bhagavad Gita, conscience is the label given to attributes composing knowledge about good and evil, that a soul acquires from the completion of acts and consequent accretion of karma over many lifetimes.[6] According to Adi Shankara in his Vivekachudamani morally right action (characterized as humbly and compassionately performing the primary duty of good to others without expectation of material or spiritual reward), helps "purify the heart" and provide mental tranquility but it alone does not give us "direct perception of the Reality."[7] This knowledge requires discrimination between the eternal and non-eternal and eventually a realization in contemplation that the true self merges in a universe of pure consciousness.[7]

In the Zoroastrian faith, after death a soul must face judgment at the Bridge of the Separator; there, evil people are tormented by prior denial of their own higher nature, or conscience, and "to all time will they be guests for the House of the Lie."[8] The Chinese concept of Ren, indicates that conscience, along with social etiquette and correct relationships, assist humans to follow The Way (Tao) a mode of life reflecting the implicit human capacity for goodness and harmony.[9]

Conscience also features prominently in Buddhism.[10] In the Pali scriptures, for example, Buddha links the positive aspect of conscience to a pure heart and a calm, well-directed mind. It is regarded as a spiritual power, and one of the “Guardians of the World”. The Buddha also associated conscience with compassion for those who must endure cravings and suffering in the world until right conduct culminates in right mindfulness and right contemplation.[11] Santideva (685–763 C.E.) wrote in the Bodhicaryavatara (which he composed and delivered in the great northern Indian Buddhist university of Nalanda) of the spiritual importance of perfecting virtues such as generosity, forbearance and training the awareness to be like a "block of wood" when attracted by vices such as pride or lust; so one can continue advancing towards right understanding in meditative absorption.[12] Conscience thus manifests in Buddhism as unselfish love for all living beings which gradually intensifies and awakens to a purer awareness where the mind withdraws from sensory interests and becomes aware of itself as a single whole.

The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote in his Meditations that conscience was the human capacity to live by rational principles that were congruent with the true, tranquil and harmonious nature of our mind and thereby that of the Universe: "To move from one unselfish action to another with God in mind. Only there, delight and stillness ... the only rewards of our existence here are an unstained character and unselfish acts."[13]

The Islamic concept of Taqwa is closely related to conscience. In the Qur’ān verses 2:197 and 22:37, Taqwa refers to "right conduct" or "piety," "guarding of oneself" or "guarding against evil."[14] Qur’an verse 47:17 says that God is the ultimate source of the believer's taqwā which is not simply the product of individual will but requires inspiration from God. In Qur’ān verses 91:7–8, God the Almighty talks about how He has perfected the soul, the conscience and has taught it the wrong (fujūr) and right (taqwā). Hence, the awareness of vice and virtue is inherent in the soul, allowing it to be tested fairly in the life of this world and tried, held accountable on the day of judgment for responsibilities to God and all humans.[15]

Qur’ān verse 49:13 states: "O humankind! We have created you out of male and female and constituted you into different groups and societies, so that you may come to know each other-the noblest of you, in the sight of God, are the ones possessing taqwā." In Islam, according to eminent theologians such as Al-Ghazali, although events are ordained (and written by God in al-Lawh al-Mahfūz, the Preserved Tablet), humans possess free will to choose between wrong and right, and are thus responsible for their actions; the conscience being a dynamic personal connection to God enhanced by knowledge and practice of the Five Pillars of Islam, deeds of piety, repentance, self-discipline, and prayer; and disintegrated and metaphorically covered in blackness through sinful acts.[8][16]

Philosophical conceptions

The Church Fathers

The notion of conscience (Latin: conscientia) in not found in ancient Greek ethical writings. However, Platonic and Aristotelian conceptions of the soul as possessing a reasoning faculty, which is responsible for choosing the correct course of action (Greek: orthos logos = right reason) were important antecedents to the conception of conscience developed in the patristic period of Christianity. Following on from the writings of Saint Paul, early Christian philosophers were concerned with the question of how pagans, who had not come to know the revealed truth of God, could justly be deprived of the means to salvation. Their response was to claim that all human beings possess a natural moral faculty—conscience—so that pagans could also come to know God’s moral laws (also revealed through revelation), and hence live morally good lives. In this respect, Saint Jerome introduced the notion of synderesis (or synteresis) to refer to a moral faculty whereby we “discern that we sin,” describing synderesis as a “spark of conscience, which was not even extinguished in the breast of Cain after he was turned out of paradise…”

Saint Thomas Aquinas

Probably because of a misinterpretation of Saint Jerome, medieval philosophers supported a sharp distinction between synderesis and conscience. Thomas Aquinas, for example, argues that the most basic principle of human conduct—that good is to be pursued and evil to be avoided—is known by the faculty of synderesis. However this basic principle is too general to help one know how to act in particular circumstances. Even if one aims to choose good, and aims to refrain from bad, this still leaves the question of which actions are good and which ones are bad in the situation. On Aquinas’ model, conscience is conceived as filling this gap. Conscience is a capacity that enables man to derive more specific principles (e.g. thou shall not kill), and also to apply these principles to a given circumstance. Even though the synderesis rule (“Do good and eschew evil”) is held to be infallible, errors in conscience are possible because one may make mistakes in deriving specific rules of conduct, or alternatively, make mistakes in applying these rules to the situation.

In Summa Theologica Thomas Aquinas discusses the moral problem of the “erring conscience.” Given that Aquinas conceives of the synderesis rule (“Do good and eschew evil”) as self-evident, an erring conscience refers either to a mistaken set of basic moral principles and values, or an inability to know which principles apply in the particular case. The moral problem of the erring conscience is that one does wrong in doing what is objectively bad. However, one also does wrong in going against conscience, that is, in doing what one believes to be bad. So, either way, the person with a distorted conscience does wrong: “unless he put away his error [he] cannot act well.”

Joseph Butler

One of the most sophisticated modern discussions of conscience is found in the writings of Joseph Butler. Butler analyzes man’s nature into a hierarchy of motivations: there are, first, the particular passions such as a hunger, thirst, and other bodily needs, compassion, love, and hate; secondly, there are there are the principles of benevolence and self-love; roughly speaking, benevolence is a desire for the happiness of others, whereas self-love is a desire for one’s own happiness. The third and most important part of Butler’s analysis of human nature is conscience, which he claims to be essential to man’s being a moral agent.[1] Butler conceives of conscience as a principle of reflection that “judges acts right or wrong and characters and motives virtuous or vicious.” He also describes conscience as a “sentiment of the understanding” and “a perception of the heart.”

On Butler’s analysis a virtuous person is someone who has all his parts functioning in a proper hierarchy. This means that particular passions are controlled by the self-love and benevolence, and these (and the particular passions) are in turn controlled by conscience. According to Butler, then, conscience rules supreme in the virtuous person.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Christian thinkers have tended to focus on conscience’s fundamental importance as a moral guide. Nietzsche, by contrast, focuses attention on what happens when conscience becomes unhealthy, that is, the notion of “bad conscience.” Nietzsche’s discussion of conscience is part of his account of the genealogy of morality, and the attendant notion of guilt. Nietzsche conceives of “bad conscience” as involving a sense of guilt and unworthiness, which comes about when one’s aggressive impulses fail to be expressed externally, so that they are suppressed and are turned inwards, directed against the self. Nietzsche’s solution to the problem of “bad conscience” involves a rejection of the morality system, which he regards as “life-denying,” and the presentation of an alternative “life-affirming” set of values.

Sigmund Freud

The “self-punitive” strand in conscience, criticized by Nietzsche, has also been discussed by Sigmund Freud. On Freud’s conceptual model, the human person is divided into id, ego, and superego. The primitive ‘it’, or id, is a natural repository of basic instincts, which Freud divides into life (eros) and death (thanatos) drives. Life drives are concerned with affection, and love, while death drives yield motives such as envy and hate. The ego (“das Ich”—German: “the I”) and super-ego develop out of the id. On Freud’s analysis, conscience is identified with super-ego, which is an internalization of the moral authority of parental figures (particularly the father). Guilt arises from the super-ego in response to aggressive or sexual impulses arising from the id, which are subject to the moral evaluation of the internalized moral authority. Conscience, or super-ego, is much more severe than a person’s actual parents; it can be a source of substantial anxiety and guilt, and sometimes, in severe cases, of suicide.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Joseph Butler, Five Sermons Preached at the Rolls Chapel and A Dissertation Upon the Nature of Virtue, ed. S. Darwall, (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Pub. Co., 1983, ISBN 978-0915145614).

- ↑ Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem : A Report on the Banality of Evil (Penguin Books, 1977).

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 1778. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 1782. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 1792. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ↑ Ninian Smart, The World's Religions (Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0521637480).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Shankara, Crest-Jewel of Discrimination, trans. Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isherwood, (Vedanta Press, 1970, ISBN 978-0874810387).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 John B. Noss, Man's Religions (Macmillan Publishing Co., 1972, ISBN 978-0023884405).

- ↑ Antonia S. Cua, Moral Vision and Tradition: Essays in Chinese Ethics (Catholic University of America Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0813208909).

- ↑ Jayne Hoose (ed.), Conscience in World Religions (University of Notre Dame Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0852443989).

- ↑ Ninian Smart, The Religious Experience of Mankind (Charles Scribner's Sons, 1969, ISBN 978-0684414348).

- ↑ Santideva, The Bodhicaryavatara, trans. Andrew Skilton and Kate Crosby, (Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0199540433).

- ↑ Marcus Aurelius, Meditations Gregory Hays (trans.), (Black and White Classics, 2014, ISBN 978-1503280465).

- ↑ Sachiko Murata and William C. Chittick, The Vision of Islam (I.B. Tauris, 2006, ISBN 978-1557785169).

- ↑ Azim Nanji, "Islamic Ethics" in Peter Singer (ed.), A Companion to Ethics (Wiley-Blackwell, 1993, ISBN 978-0631187851).

- ↑ Marshall G.S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam, Volume 1: The Classical Age of Islam (University of Chicago Press, 1977, ISBN 978-0226346830).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aquinas, Thomas. Summa theologiae (Synopsis of Theology), ed. T. Gilby. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1970, vol. 11, Ia.79.11-13; 1966, vol. 18, IaIIae.19.5-8.

- Arendt, Hannah. Eichmann in Jerusalem : A Report on the Banality of Evil. Penguin Classics, 2006 (original 1977). ISBN 978-0143039884

- Aurelius, Marcus, Gregory Hays (trans.). Meditations. Black and White Classics, 2014. ISBN 978-1503280465

- Butler, Joseph. Five Sermons Preached at the Rolls Chapel and A Dissertation Upon the Nature of Virtue, ed. S. Darwall. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Pub. Co., 1983. ISBN 978-0915145614

- Cua, Antonia S. Moral Vision and Tradition: Essays in Chinese Ethics. Catholic University of America Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0813208909

- Davies, Brian. The Thought of Thomas Aquinas. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992. ISBN 9780198267539

- Dolan, Joseph V. "Conscience in the Catholic Theological Tradition." In Conscience: Its Freedom and Limitations, William C. Bier (editor). Fordham University Press, 1971. ISBN 0823209059

- Freud, Sigmund. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. London: Hogarth Press, 1955. ISBN 0876681356

- Hodgson, Marshall G.S. The Venture of Islam, Volume 1: The Classical Age of Islam. University of Chicago Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0226346830

- Hoose, Jayne (ed.). Conscience in World Religions. University of Notre Dame Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0852443989

- Langston, Douglas C. Conscience and Other Virtues. From Bonaventure to MacIntyre. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001. ISBN 0271020709

- Murata, Sachiko, and William C. Chittick. The Vision of Islam. I.B. Tauris, 2006. ISBN 978-1557785169

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. On the Genealogy of Morality. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company, 1998. ISBN 978-0872202832

- Noss, John B. Man's Religions. Macmillan Publishing Co., 1972. ISBN 978-0023884405

- Potts, Timothy C. Conscience in Medieval Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, 1980. ISBN 0521232872

- Santideva, trans. Andrew Skilton and Kate Crosby. The Bodhicaryavatara. Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0199540433

- Shankara, trans. Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isherwood. Crest-Jewel of Discrimination. Vedanta Press, 1970. ISBN 978-0874810387

- Singer, Peter (ed.). A Companion to Ethics. Wiley-Blackwell, 1993. ISBN 978-0631187851

- Smart, Ninian. The Religious Experience of Mankind. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1969. ISBN 978-0684414348

- Smart, Ninian. The World's Religions. Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0521637480

- Zachman, Randall C. The Assurance of Faith. Conscience in the Theology of Martin Luther and John Calvin. Augsburg Fortress Press, Minneapolis, 1993. ISBN 0800625749

External links

All links retrieved March 21, 2023.

- Quotations about Conscience at Liberty-tree.ca.

- Conscience Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Medieval Theories of Conscience Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

| Philosophy | |

|---|---|

| Topics | Category listings | Eastern philosophy · Western philosophy | History of philosophy (ancient • medieval • modern • contemporary) |

| Lists | Basic topics · Topic list · Philosophers · Philosophies · Glossary · Movements · More lists |

| Branches | Aesthetics · Ethics · Epistemology · Logic · Metaphysics · Political philosophy |

| Philosophy of | Education · Economics · Geography · Information · History · Human nature · Language · Law · Literature · Mathematics · Mind · Philosophy · Physics · Psychology · Religion · Science · Social science · Technology · Travel ·War |

| Schools | Actual Idealism · Analytic philosophy · Aristotelianism · Continental Philosophy · Critical theory · Deconstructionism · Deontology · Dialectical materialism · Dualism · Empiricism · Epicureanism · Existentialism · Hegelianism · Hermeneutics · Humanism · Idealism · Kantianism · Logical Positivism · Marxism · Materialism · Monism · Neoplatonism · New Philosophers · Nihilism · Ordinary Language · Phenomenology · Platonism · Positivism · Postmodernism · Poststructuralism · Pragmatism · Presocratic · Rationalism · Realism · Relativism · Scholasticism · Skepticism · Stoicism · Structuralism · Utilitarianism · Virtue Ethics |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.