Difference between revisions of "Adultery" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) (copied from wikipedia) |

|||

| (60 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Law]] | [[Category:Law]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Sociology]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Lifestyle]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Marriage and family]] | ||

| + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{FamilyLaw}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Adultery''' is generally defined as consensual [[human sexuality|sexual intercourse]] by a [[marriage|married]] person with someone other than his or her lawful spouse. Thus, adultery is a special case of [[fornication]], which refers to consensual sexual intercourse between two people not married to each other. The common synonym for adultery is [[infidelity]] as well as unfaithfulness or in colloquial speech, "cheating." | |

| − | + | Views on the gravity of adultery have varied across [[culture]]s and [[religion]]s. Generally, since most have considered marriage an inviolable if not [[sacred]] commitment, adultery has been strictly censured and severely [[punishment|punished]]. For any society in which [[monogamy]] is the [[norm]], adultery is a serious violation on all levels—the individuals involved, the spouse and [[family]] of the perpetrator, and the larger [[community]] for whom the family is the building block and the standard or "school" for interpersonal relationships. The [[Sexual Revolution]] of the mid-twentieth century loosened strictures on sexual behavior such that fornication was no longer considered outside the norms of behavior and certainly not criminal if both parties were of age. Nevertheless, adultery still has serious ramifications and is considered sufficient cause for [[divorce]]. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | From a spiritual perspective, however, the act of adultery causes more than just [[emotion]]al or legal problems. The violation of trust involved in sexual activity with someone while married to another is deep, and sexual intimacy is not just a physical and emotional experience but a spiritual one. When one has a sexual relationship with another it is not just their "heart" that is given but their [[soul]]. While the heart cannot be taken back and mended without difficulty, it is all but impossible to take back the soul. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Definitions== |

| − | + | '''Fornication''' is a term which refers to any [[Human sexuality|sexual activity]] between [[marriage|unmarried]] partners. '''Adultery''', on the other hand, refers specifically to extramarital sexual relations in which at least one of the parties is married (to someone else) when the act is committed. | |

| − | + | Adultery was known in earlier times by the legalistic term "criminal conversation" (another term, [[alienation of affection]], is used when one spouse deserts the other for a third person). The term originates not from ''[[adult]]'', which is from [[Latin]] a-dolescere, to grow up, mature, a combination of ''a'', "to," ''dolere'', "work," and the processing combound ''sc''), but from the Latin ''ad-ulterare'' (to commit adultery, adulterate/falsify, a combination of ''ad,'' "at," and ''ulter,'' "above," "beyond," "opposite," meaning "on the other side of the bond of marriage").<ref>''Longman Dictionary of Latin.'' (Berlin: Longman, 1950).</ref> | |

| − | + | Today, although the definition of "adultery" finds various expressions in different legal systems, the common theme is sexual activity between persons when one of both is married to someone else. | |

| − | + | For example, [[New York]] State defines an adulterer as a person who "engages in sexual intercourse with another person at a time when he has a living spouse, or the other person has a living spouse."<ref>[https://www.lectlaw.com/files/sex09.htm Minnes 130.00 Sex offenses; definitions of terms] New York State Sexual Statutes, The 'Lectric Law Library. Retrieved June 6, 2019.</ref> | |

| − | + | A marriage in which both spouses agree that it is acceptable for the husband or wife to have sexual relationships with other people other than their spouse is a form of non-[[monogamy]]. The resulting sexual relationships the husband or wife may have with other people, although could be considered to be adultery in some legal jurisdictions, are not treated as such by the spouses. | |

| − | == | + | ==Laws and penalties== |

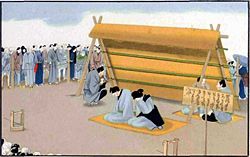

| − | + | [[Image:Man and woman undergoing public exposure for adultery in Japan-J. M. W. Silver.jpg|thumb|250px|Man and woman undergoing public exposure for adultery in Japan, around 1860]] | |

| − | + | ===Adultery=== | |

| + | Historically, adultery has been subject to severe [[punishment]]s including the [[death penalty]] and has been grounds for [[divorce]] under fault-based divorce [[family law|laws]]. In some places the death penalty for adultery has been carried out by [[stoning]].<ref>[http://edition.cnn.com/2003/WORLD/africa/09/19/nigeria.stoning/ Anger over adultery stoning case] ''CNN'', February 23, 2004. Retrieved June 6, 2019.</ref> | ||

| − | + | For example, the influential [[Code of Hammurabi]] contains a section on adultery. It mirrors the customs of earlier societies in bringing harsh penalties upon those found guilty of adultery. The punishment prescribed in Hammurabi's Code was death by drowning or burning for both the unfaithful spouse and the external seducer. The pair could be spared if the wronged spouse pardoned the adulterer, but even still the king had to intervene to spare the lovers' lives. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | {{readout|In some cultures, adultery was defined as a crime only when a wife had sexual relations with a man who was not her husband; a husband could be unfaithful to his wife without it being considered adultery.|left}} For example, in the Graeco-Roman world we find stringent laws against adultery, yet almost throughout they discriminate against the wife. The ancient idea that the wife was the [[property]] of the husband is still operative. The lending of wives was, as [[Plutarch]] tells us, encouraged also by Lycurgus.<ref>Plutarch, "Lycurgus" XXIX, ''Plutarch Lives, I, Theseus and Romulus. Lycurgus and Numa. Solon and Publicola'' (Loeb Classical Library, 1914, ISBN 0674990528).</ref> There was, therefore, no such thing as the crime of adultery on the part of a husband towards his wife. The recognized license of the Greek husband may be seen in the following passage of the Oration against Neaera, the author of which is uncertain though it has been attributed to [[Demosthenes]]: | |

| + | <blockquote>We keep mistresses for our pleasures, concubines for constant attendance, and wives to bear us legitimate children, and to be our faithful housekeepers. Yet, because of the wrong done to the husband only, the Athenian lawgiver Solon, allowed any man to kill an adulterer whom he had taken in the act.<ref>Plutarch, "Solon," ''Plutarch Lives, I, Theseus and Romulus. Lycurgus and Numa. Solon and Publicola'' (Loeb Classical Library, 1914, ISBN 0674990528).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Later on in Roman history, as William Lecky has shown, the idea that the husband owed a fidelity like that demanded of the wife must have gained ground at least in theory. This Lecky gathers from the [[legal maxim]] of [[Ulpian]]: "It seems most unfair for a man to require from a wife the chastity he does not himself practice."<ref>William Lecky, "Codex Justin., Digest, XLVIII, 5-13" ''History of European Morals'' (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2005, ISBN 1425548385).</ref> | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Jules Arsène Garnier - Le supplice des adultères.jpg|thumb|right|275 px|''Le supplice des adultères,'' Jules Arsène Garnier]] |

| − | ''' | ||

| − | + | In the original [[Napoleonic Code]], a man could ask to be divorced from his wife if she committed adultery, but the adultery of the husband was not a sufficient motive unless he had kept his [[concubine]] in the family home. | |

| − | + | In contemporary times in the [[United States]] laws vary from state to state. For example, in [[Pennsylvania]], adultery is technically punishable by two years of imprisonment or 18 months of treatment for insanity.<ref>Ronald Hamowy, ''Medicine and the Crimination of Sin: "Self-Abuse" in 19th Century America.'' 2, 3 [https://www.mises.org/journals/jls/1_3/1_3_8.pdf ''Medicine and the Crimination of Sin: Self-Abuse''] Retrieved June 6, 2019.</ref> That being said, such statutes are typically considered [[blue law]]s, and are rarely, if ever, enforced. | |

| − | + | In the [[U.S. Military]], adultery is a [[court-martial]]able offense only if it was "to the prejudice of good order and discipline" or "of a nature to bring discredit upon the armed forces."<ref>Rod Powers, [https://www.thebalancecareers.com/adultery-in-the-military-3354158 Adultery in the Military] ''US Military Careers'', November 1, 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2019.</ref> This has been applied to cases where both partners were members of the military, particularly where one is in command of the other, or one partner and the other's spouse. The enforceability of criminal sanctions for adultery is very questionable in light of [[Supreme Court of the United States|Supreme Court]] decisions since 1965 relating to privacy and sexual intimacy, and particularly in light of ''[[Lawrence v. Texas]],'' which apparently recognized a broad constitutional right of sexual intimacy for consenting adults. | |

| − | + | ===Fornication=== | |

| + | The laws on fornication have historically been tied with [[religion]], however in many countries there have been attempts to secularize constitutions, and laws differ greatly from country to country. Rather than varying greatly along national lines, views on fornication are often determined by religion, which can cross borders. | ||

| − | + | Laws dealing with fornication are usually defined as intercourse between two unmarried persons of the opposite gender. These have been mostly repealed, not enforced, or struck down in various courts in the western world.<ref>''State of New Jersey v. Saunders'', 381 A.2d 333 (N.J. 1977), ''Martin v. Ziherl'' 607 S.E.2d 367 (Va. 2005). </ref> | |

| − | + | Fornication is a [[crime]] in many [[Muslim]] countries, and is often harshly punished. However, there are some exceptions. In certain countries where parts of [[Islamic law]] are enforced, such as [[Iran]] and [[Saudi Arabia]], fornication of unmarried persons is punishable by lashings. This is in contrast to adultery, where if one of the convicted were married, their punishment would be [[death penalty|death]] by stoning. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Religious Views== | |

| + | Among the world religions, adultery and fornication are generally considered major [[sin]]s: <blockquote>No other sin has such a baneful effect on the spiritual life. Because it is committed in secret, by mutual consent, and often without fear of the law, adultery is especially a sin against God and against the goal of life. Modern secular societies can do little to inhibit adultery and sexual promiscuity. Only the norms of morality which are founded on religion can effectively curb this sin.<ref>Andrew Wilson (ed.), [http://www.unification.net/ws/theme059.htm Adultery] ''World Scripture'' (1991). Retrieved June 6, 2019.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | [[ | + | ===Judaism=== |

| − | + | In [[Judaism]], adultery was forbidden in the seventh commandment of the [[Ten Commandments]], but this did not apply to a married man having relations with an unmarried woman. Only a married woman engaging in sexual intercourse with another man counted as adultery, in which case both the woman and the man were considered guilty.<ref>David Werner Amram, [http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/865-adultery Adultery] ''Jewish Encyclopedia''. Retrieved June 6, 2019.</ref> | |

| − | The | + | In the Mosaic Law, as in the old Roman Law, adultery meant only the carnal intercourse of a wife with a man who was not her lawful husband. The intercourse of a married man with a single woman was not accounted adultery, but fornication. The penal statute on the subject, in [[Leviticus]], 20:10, makes this clear: "If any man commit adultery with the wife of another and defile his neighbor's wife let them be put to death both the adulterer and the adulteress" (also [[Deuteronomy]] 22:22). This was quite in keeping with the prevailing practice of [[polygyny]] among the Israelites. |

| + | |||

| + | In [[halakha]] (Jewish Law) the penalty for adultery is stoning for both the man and the woman, but this is only enacted when there are two independent witnesses who warned the sinners prior to the crime being committed. Hence this is rarely carried out. However a man is not allowed to continue living with a wife who cheated on him, and is obliged to give her a "[[get (divorce document)|get]]" or bill of [[divorce]] written by a [[sofer]] or scribe. | ||

| − | + | The Hebrew word translated “fornication” in the Old Testament was also used in the context of [[idolatry]], called "spiritual whoredom." Israel’s idolatry is often described as a wanton woman who went “whoring after” other gods (Exodus 34:15-16; Leviticus 17:7; Ezekiel 6:9 KJV).<ref>[http://www.gotquestions.org/fornication-adultery.html What is the difference between fornication and adultery?] GotQuestions.org. Retrieved June 6, 2019.</ref> | |

| − | The | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Christianity=== | |

| + | Throughout the [[Old Testament]], adultery is forbidden in the [[Ten Commandments]], and punishable by death. In the [[New Testament]], [[Jesus]] preached that adultery was a [[sin]] but did not enforce the punishment, reminding the people that they had all sinned. In John 8:1-11, some [[Pharisees]] brought Jesus a woman accused of committing adultery. After reminding Jesus that her punishment should be [[stoning]], the Pharisees asked Jesus what should be done. Jesus responded, "If any one of you is without sin, let him be the first to throw a stone at her."<ref>[https://biblehub.com/john/8-7.htm John 8:7] ''BibleHub''. Retrieved June 4, 2019.</ref> Jesus then forgave the woman and told her not to commit adultery. | ||

| − | + | [[Paul of Tarsus|Saint Paul]] put men and women on the same footing with regard to marital rights.<ref>[https://biblehub.com/1_corinthians/7-3.htm 1 Corinthians 7:3] ''BibleHub''. Retrieved June 4, 2019.</ref> This contradicted the traditional notion that relations of a married man with an unmarried woman were not adultery. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | This parity between husband and wife was insisted on by early Christian writers such as Lactantius, who declared: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>For he is equally an adulterer in the sight of God and impure, who, having thrown off the yoke, wantons in strange pleasure either with a free woman or a slave. But as a woman is bound by the bonds of chastity not to desire any other man, so let the husband be bound by the same law, since God has joined together the husband and the wife in the union of one body.<ref>[http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf07.iii.ii.viii.lxii.html ''Epitome of the Divine Institutes'', chapter 56] Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved June 9, 2019.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | + | In the sixteenth century, the Catechism of the [[Council of Trent]] defined adultery as follows: | |

| + | <blockquote>To begin with the prohibitory part (of the Commandment), adultery is the defilement of the marriage bed, whether it be one's own or another's. If a married man have intercourse with an unmarried woman, he violates the integrity of his marriage bed; and if an unmarried man have intercourse with a married woman, he defiles the sanctity of the marriage bed of another.<ref>[http://www.cin.org/users/james/ebooks/master/trent/tcomm06.htm ''The Catechism of Trent'']. ''Nazareth Resource Library''. Retrieved June 6, 2019.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | == | + | ===Islam=== |

| − | + | In the [[Qur'an]], sexual activity before [[marriage]] is strictly prohibited. [[Islam]] stresses that sexual relations should be restricted to the institution of [[marriage]] in order for the creation of the [[family]]; and secondly, as a means to protect the family, certain relations should be considered prohibited outside of marriage. | |

| − | + | Premarital and extramarital sex (adultery) are both included in the Arabic word ''[[Zina]].'' Belonging primarily to the same category of [[crime]]s, entailing the same social implications, and having the same effects on the spiritual personality of a [[human being]], both, in principle, have been given the same status by the Qur'an. Zina is considered a great [[sin]] in Islam, whether it is before marriage or after marriage. In addition to the [[punishment]]s rendered before death, sinners can expect to be punished severely after death, unless purged of their sins by a punishment according to [[Shari'a]] law. | |

| − | + | ===Hinduism=== | |

| + | [[Hinduism]], by the holy book, the ''[[Bhagavad Gita]],'' forbids acts of fornication. It is considered offensive in Hindu society as well, and it is still forbidden by Hindu law. | ||

| − | + | Alternative Hindu schools of thought such as the [[Tantra|Tantric]] branches of Hinduism, the Hindu practices native to [[India]] that predates centuries of conservative Islamic influence, is markedly less reserved, teaching that [[enlightenment]] can be approached through divine sex. Divine sex is one path whereby one can approach [[Moksha]], a oneness with a higher spiritual level. As such, the Tantric practices seek not to repress sexuality, but to perfect it. By perfecting the act of divine sex, one clears the mind of earthly desires, leaving the [[soul]] on a higher level devoid of such worries, filled with bliss, and relaxed. | |

| − | == | + | ===Buddhism=== |

| − | + | In the [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] tradition, under the [[Five Precepts]] and the [[Eightfold Path]], one should neither be attached to nor crave sensual pleasure. The third of the Five Precepts is "To refrain from sexual misconduct." For most Buddhist laypeople, sex outside of marriage is not "sexual misconduct," especially when compared to, say, adultery or any sexual activity which can bring suffering to another human being. Each may need to consider whether, for them, sexual contact is a distraction or means of avoidance of their own spiritual practice or development. To provide a complete focus onto spiritual practice, fully ordained Buddhist monks may, depending on the tradition, be bound by hundreds of further detailed rules or vows that may include a ban on sexual relations. [[Vajrayana]] or Tantric Buddhism, on the other hand, teaches that sexual intercourse can be actively used to approach higher spiritual development. | |

| − | + | ==Adultery in Literature== | |

| + | The theme of adultery features in a wide range of [[literature]] through the ages. As [[marriage]] and [[family]] are often regarded as basis of society a story of adultery often shows the [[conflict]] between social pressure and individual struggle for [[happiness]]. | ||

| − | + | In the [[Bible]], incidents of adultery are present almost from the start. The story of [[Abraham]] contains several incidents and serve as warnings or stories of [[sin]] and [[forgiveness]]. Abraham attempts to continue his blood line through his wife's maidservant, with consequences that continue through history. [[Jacob]]'s family life is complicated with similar incidents. | |

| − | + | [[William Shakespeare|Shakespeare]] wrote three plays in which the perception of adultery plays a significant part. In both ''[[Othello]]'' and ''[[The Winter's Tale]]'' it is the (false) belief by the central character that his wife is unfaithful that brings about his downfall. In "[[The Merry Wives of Windsor]]," an adulterous plot by Falstaff prompts elaborate and repeated revenge by the wronged wives; the comedy of the play hides a deeper anxiety about the infidelity of women. | |

| − | + | In ''[[The Country Wife]]'' by [[William Wycherley]], the morals of [[English Restoration]] society are satirized. The object of the hero is to seduce as many married ladies as possible, while blinding their husbands to what is going on by pretending to be [[impotence|impotent]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Other acclaimed authors who have featured adultery in their novels include [[F. Scott Fitzgerald]] in his work, ''[[The Great Gatsby]],'' [[Nathaniel Hawthorne]] in ''[[The Scarlet Letter]],'' and [[John Irving]] in ''[[The World According to Garp]].'' | |

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| − | + | <references /> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | *Glass, S.P., and T.L. Wright. "Justifications for extramarital relationships: The association between attitudes, behaviors, and gender," ''Journal of Sex Research'', 29 (1992): 361-387. |

| − | + | *Hamowy, Ronald. [https://www.mises.org/journals/jls/1_3/1_3_8.pdf ''Medicine and the Crimination of Sin: Self-Abuse'']. Retrieved June 11, 2019. | |

| − | + | *Lecky, William. ''History of European morals from Augustus to Charlemagne''. Scholarly Publishing Office, University of Michigan Library. 2005. ISBN 1425548385 | |

| − | + | *Moultrup, David J. ''Husbands, Wives & Lovers''. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 1990. ISBN 0898621054 | |

| − | + | *Pittman, F. ''Private Lies: Infidelity and Betrayal of Intimacy''. New York, NY: W. W. Norton Co., 1989. ISBN 0393307077 | |

| − | + | *Rubin, A.M., & J.R. Adams. "Outcomes of sexually open marriages," ''Journal of Sex Research'' 22 (1986): 311-319. | |

| − | * | + | *Vaughan, P. ''The Monogamy Myth''. New York, NY: New Market Press, 1989. ISBN 1557045429 |

| − | * | + | *Wilson, Andrew (ed.). ''World Scripture: A Comparative Anthology of Sacred Texts''. New York, NY: Paragon House, 1991. ISBN 0892261293 |

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | + | {{Credits|Adultery|77465492|Adultery_in_literature|77441224|Fornication|77652176|}} |

Latest revision as of 17:15, 8 September 2019

|

| Family law |

|---|

| Entering into marriage |

| Marriage |

| Common-law marriage |

| Dissolution of marriage |

| Annulment |

| Divorce |

| Alimony |

| Issues affecting children |

| Illegitimacy |

| Adoption |

| Child support |

| Foster care |

| Areas of possible legal concern |

| Domestic violence |

| Child abuse |

| Adultery |

| Polygamy |

| Incest |

Adultery is generally defined as consensual sexual intercourse by a married person with someone other than his or her lawful spouse. Thus, adultery is a special case of fornication, which refers to consensual sexual intercourse between two people not married to each other. The common synonym for adultery is infidelity as well as unfaithfulness or in colloquial speech, "cheating."

Views on the gravity of adultery have varied across cultures and religions. Generally, since most have considered marriage an inviolable if not sacred commitment, adultery has been strictly censured and severely punished. For any society in which monogamy is the norm, adultery is a serious violation on all levels—the individuals involved, the spouse and family of the perpetrator, and the larger community for whom the family is the building block and the standard or "school" for interpersonal relationships. The Sexual Revolution of the mid-twentieth century loosened strictures on sexual behavior such that fornication was no longer considered outside the norms of behavior and certainly not criminal if both parties were of age. Nevertheless, adultery still has serious ramifications and is considered sufficient cause for divorce.

From a spiritual perspective, however, the act of adultery causes more than just emotional or legal problems. The violation of trust involved in sexual activity with someone while married to another is deep, and sexual intimacy is not just a physical and emotional experience but a spiritual one. When one has a sexual relationship with another it is not just their "heart" that is given but their soul. While the heart cannot be taken back and mended without difficulty, it is all but impossible to take back the soul.

Definitions

Fornication is a term which refers to any sexual activity between unmarried partners. Adultery, on the other hand, refers specifically to extramarital sexual relations in which at least one of the parties is married (to someone else) when the act is committed.

Adultery was known in earlier times by the legalistic term "criminal conversation" (another term, alienation of affection, is used when one spouse deserts the other for a third person). The term originates not from adult, which is from Latin a-dolescere, to grow up, mature, a combination of a, "to," dolere, "work," and the processing combound sc), but from the Latin ad-ulterare (to commit adultery, adulterate/falsify, a combination of ad, "at," and ulter, "above," "beyond," "opposite," meaning "on the other side of the bond of marriage").[1]

Today, although the definition of "adultery" finds various expressions in different legal systems, the common theme is sexual activity between persons when one of both is married to someone else.

For example, New York State defines an adulterer as a person who "engages in sexual intercourse with another person at a time when he has a living spouse, or the other person has a living spouse."[2]

A marriage in which both spouses agree that it is acceptable for the husband or wife to have sexual relationships with other people other than their spouse is a form of non-monogamy. The resulting sexual relationships the husband or wife may have with other people, although could be considered to be adultery in some legal jurisdictions, are not treated as such by the spouses.

Laws and penalties

Adultery

Historically, adultery has been subject to severe punishments including the death penalty and has been grounds for divorce under fault-based divorce laws. In some places the death penalty for adultery has been carried out by stoning.[3]

For example, the influential Code of Hammurabi contains a section on adultery. It mirrors the customs of earlier societies in bringing harsh penalties upon those found guilty of adultery. The punishment prescribed in Hammurabi's Code was death by drowning or burning for both the unfaithful spouse and the external seducer. The pair could be spared if the wronged spouse pardoned the adulterer, but even still the king had to intervene to spare the lovers' lives.

In some cultures, adultery was defined as a crime only when a wife had sexual relations with a man who was not her husband; a husband could be unfaithful to his wife without it being considered adultery. For example, in the Graeco-Roman world we find stringent laws against adultery, yet almost throughout they discriminate against the wife. The ancient idea that the wife was the property of the husband is still operative. The lending of wives was, as Plutarch tells us, encouraged also by Lycurgus.[4] There was, therefore, no such thing as the crime of adultery on the part of a husband towards his wife. The recognized license of the Greek husband may be seen in the following passage of the Oration against Neaera, the author of which is uncertain though it has been attributed to Demosthenes:

We keep mistresses for our pleasures, concubines for constant attendance, and wives to bear us legitimate children, and to be our faithful housekeepers. Yet, because of the wrong done to the husband only, the Athenian lawgiver Solon, allowed any man to kill an adulterer whom he had taken in the act.[5]

Later on in Roman history, as William Lecky has shown, the idea that the husband owed a fidelity like that demanded of the wife must have gained ground at least in theory. This Lecky gathers from the legal maxim of Ulpian: "It seems most unfair for a man to require from a wife the chastity he does not himself practice."[6]

In the original Napoleonic Code, a man could ask to be divorced from his wife if she committed adultery, but the adultery of the husband was not a sufficient motive unless he had kept his concubine in the family home.

In contemporary times in the United States laws vary from state to state. For example, in Pennsylvania, adultery is technically punishable by two years of imprisonment or 18 months of treatment for insanity.[7] That being said, such statutes are typically considered blue laws, and are rarely, if ever, enforced.

In the U.S. Military, adultery is a court-martialable offense only if it was "to the prejudice of good order and discipline" or "of a nature to bring discredit upon the armed forces."[8] This has been applied to cases where both partners were members of the military, particularly where one is in command of the other, or one partner and the other's spouse. The enforceability of criminal sanctions for adultery is very questionable in light of Supreme Court decisions since 1965 relating to privacy and sexual intimacy, and particularly in light of Lawrence v. Texas, which apparently recognized a broad constitutional right of sexual intimacy for consenting adults.

Fornication

The laws on fornication have historically been tied with religion, however in many countries there have been attempts to secularize constitutions, and laws differ greatly from country to country. Rather than varying greatly along national lines, views on fornication are often determined by religion, which can cross borders.

Laws dealing with fornication are usually defined as intercourse between two unmarried persons of the opposite gender. These have been mostly repealed, not enforced, or struck down in various courts in the western world.[9]

Fornication is a crime in many Muslim countries, and is often harshly punished. However, there are some exceptions. In certain countries where parts of Islamic law are enforced, such as Iran and Saudi Arabia, fornication of unmarried persons is punishable by lashings. This is in contrast to adultery, where if one of the convicted were married, their punishment would be death by stoning.

Religious Views

Among the world religions, adultery and fornication are generally considered major sins:

No other sin has such a baneful effect on the spiritual life. Because it is committed in secret, by mutual consent, and often without fear of the law, adultery is especially a sin against God and against the goal of life. Modern secular societies can do little to inhibit adultery and sexual promiscuity. Only the norms of morality which are founded on religion can effectively curb this sin.[10]

Judaism

In Judaism, adultery was forbidden in the seventh commandment of the Ten Commandments, but this did not apply to a married man having relations with an unmarried woman. Only a married woman engaging in sexual intercourse with another man counted as adultery, in which case both the woman and the man were considered guilty.[11]

In the Mosaic Law, as in the old Roman Law, adultery meant only the carnal intercourse of a wife with a man who was not her lawful husband. The intercourse of a married man with a single woman was not accounted adultery, but fornication. The penal statute on the subject, in Leviticus, 20:10, makes this clear: "If any man commit adultery with the wife of another and defile his neighbor's wife let them be put to death both the adulterer and the adulteress" (also Deuteronomy 22:22). This was quite in keeping with the prevailing practice of polygyny among the Israelites.

In halakha (Jewish Law) the penalty for adultery is stoning for both the man and the woman, but this is only enacted when there are two independent witnesses who warned the sinners prior to the crime being committed. Hence this is rarely carried out. However a man is not allowed to continue living with a wife who cheated on him, and is obliged to give her a "get" or bill of divorce written by a sofer or scribe.

The Hebrew word translated “fornication” in the Old Testament was also used in the context of idolatry, called "spiritual whoredom." Israel’s idolatry is often described as a wanton woman who went “whoring after” other gods (Exodus 34:15-16; Leviticus 17:7; Ezekiel 6:9 KJV).[12]

Christianity

Throughout the Old Testament, adultery is forbidden in the Ten Commandments, and punishable by death. In the New Testament, Jesus preached that adultery was a sin but did not enforce the punishment, reminding the people that they had all sinned. In John 8:1-11, some Pharisees brought Jesus a woman accused of committing adultery. After reminding Jesus that her punishment should be stoning, the Pharisees asked Jesus what should be done. Jesus responded, "If any one of you is without sin, let him be the first to throw a stone at her."[13] Jesus then forgave the woman and told her not to commit adultery.

Saint Paul put men and women on the same footing with regard to marital rights.[14] This contradicted the traditional notion that relations of a married man with an unmarried woman were not adultery.

This parity between husband and wife was insisted on by early Christian writers such as Lactantius, who declared:

For he is equally an adulterer in the sight of God and impure, who, having thrown off the yoke, wantons in strange pleasure either with a free woman or a slave. But as a woman is bound by the bonds of chastity not to desire any other man, so let the husband be bound by the same law, since God has joined together the husband and the wife in the union of one body.[15]

In the sixteenth century, the Catechism of the Council of Trent defined adultery as follows:

To begin with the prohibitory part (of the Commandment), adultery is the defilement of the marriage bed, whether it be one's own or another's. If a married man have intercourse with an unmarried woman, he violates the integrity of his marriage bed; and if an unmarried man have intercourse with a married woman, he defiles the sanctity of the marriage bed of another.[16]

Islam

In the Qur'an, sexual activity before marriage is strictly prohibited. Islam stresses that sexual relations should be restricted to the institution of marriage in order for the creation of the family; and secondly, as a means to protect the family, certain relations should be considered prohibited outside of marriage.

Premarital and extramarital sex (adultery) are both included in the Arabic word Zina. Belonging primarily to the same category of crimes, entailing the same social implications, and having the same effects on the spiritual personality of a human being, both, in principle, have been given the same status by the Qur'an. Zina is considered a great sin in Islam, whether it is before marriage or after marriage. In addition to the punishments rendered before death, sinners can expect to be punished severely after death, unless purged of their sins by a punishment according to Shari'a law.

Hinduism

Hinduism, by the holy book, the Bhagavad Gita, forbids acts of fornication. It is considered offensive in Hindu society as well, and it is still forbidden by Hindu law.

Alternative Hindu schools of thought such as the Tantric branches of Hinduism, the Hindu practices native to India that predates centuries of conservative Islamic influence, is markedly less reserved, teaching that enlightenment can be approached through divine sex. Divine sex is one path whereby one can approach Moksha, a oneness with a higher spiritual level. As such, the Tantric practices seek not to repress sexuality, but to perfect it. By perfecting the act of divine sex, one clears the mind of earthly desires, leaving the soul on a higher level devoid of such worries, filled with bliss, and relaxed.

Buddhism

In the Buddhist tradition, under the Five Precepts and the Eightfold Path, one should neither be attached to nor crave sensual pleasure. The third of the Five Precepts is "To refrain from sexual misconduct." For most Buddhist laypeople, sex outside of marriage is not "sexual misconduct," especially when compared to, say, adultery or any sexual activity which can bring suffering to another human being. Each may need to consider whether, for them, sexual contact is a distraction or means of avoidance of their own spiritual practice or development. To provide a complete focus onto spiritual practice, fully ordained Buddhist monks may, depending on the tradition, be bound by hundreds of further detailed rules or vows that may include a ban on sexual relations. Vajrayana or Tantric Buddhism, on the other hand, teaches that sexual intercourse can be actively used to approach higher spiritual development.

Adultery in Literature

The theme of adultery features in a wide range of literature through the ages. As marriage and family are often regarded as basis of society a story of adultery often shows the conflict between social pressure and individual struggle for happiness.

In the Bible, incidents of adultery are present almost from the start. The story of Abraham contains several incidents and serve as warnings or stories of sin and forgiveness. Abraham attempts to continue his blood line through his wife's maidservant, with consequences that continue through history. Jacob's family life is complicated with similar incidents.

Shakespeare wrote three plays in which the perception of adultery plays a significant part. In both Othello and The Winter's Tale it is the (false) belief by the central character that his wife is unfaithful that brings about his downfall. In "The Merry Wives of Windsor," an adulterous plot by Falstaff prompts elaborate and repeated revenge by the wronged wives; the comedy of the play hides a deeper anxiety about the infidelity of women.

In The Country Wife by William Wycherley, the morals of English Restoration society are satirized. The object of the hero is to seduce as many married ladies as possible, while blinding their husbands to what is going on by pretending to be impotent.

Other acclaimed authors who have featured adultery in their novels include F. Scott Fitzgerald in his work, The Great Gatsby, Nathaniel Hawthorne in The Scarlet Letter, and John Irving in The World According to Garp.

Notes

- ↑ Longman Dictionary of Latin. (Berlin: Longman, 1950).

- ↑ Minnes 130.00 Sex offenses; definitions of terms New York State Sexual Statutes, The 'Lectric Law Library. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ↑ Anger over adultery stoning case CNN, February 23, 2004. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ↑ Plutarch, "Lycurgus" XXIX, Plutarch Lives, I, Theseus and Romulus. Lycurgus and Numa. Solon and Publicola (Loeb Classical Library, 1914, ISBN 0674990528).

- ↑ Plutarch, "Solon," Plutarch Lives, I, Theseus and Romulus. Lycurgus and Numa. Solon and Publicola (Loeb Classical Library, 1914, ISBN 0674990528).

- ↑ William Lecky, "Codex Justin., Digest, XLVIII, 5-13" History of European Morals (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2005, ISBN 1425548385).

- ↑ Ronald Hamowy, Medicine and the Crimination of Sin: "Self-Abuse" in 19th Century America. 2, 3 Medicine and the Crimination of Sin: Self-Abuse Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ↑ Rod Powers, Adultery in the Military US Military Careers, November 1, 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ↑ State of New Jersey v. Saunders, 381 A.2d 333 (N.J. 1977), Martin v. Ziherl 607 S.E.2d 367 (Va. 2005).

- ↑ Andrew Wilson (ed.), Adultery World Scripture (1991). Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ↑ David Werner Amram, Adultery Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ↑ What is the difference between fornication and adultery? GotQuestions.org. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ↑ John 8:7 BibleHub. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 7:3 BibleHub. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ↑ Epitome of the Divine Institutes, chapter 56 Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ↑ The Catechism of Trent. Nazareth Resource Library. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Glass, S.P., and T.L. Wright. "Justifications for extramarital relationships: The association between attitudes, behaviors, and gender," Journal of Sex Research, 29 (1992): 361-387.

- Hamowy, Ronald. Medicine and the Crimination of Sin: Self-Abuse. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- Lecky, William. History of European morals from Augustus to Charlemagne. Scholarly Publishing Office, University of Michigan Library. 2005. ISBN 1425548385

- Moultrup, David J. Husbands, Wives & Lovers. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 1990. ISBN 0898621054

- Pittman, F. Private Lies: Infidelity and Betrayal of Intimacy. New York, NY: W. W. Norton Co., 1989. ISBN 0393307077

- Rubin, A.M., & J.R. Adams. "Outcomes of sexually open marriages," Journal of Sex Research 22 (1986): 311-319.

- Vaughan, P. The Monogamy Myth. New York, NY: New Market Press, 1989. ISBN 1557045429

- Wilson, Andrew (ed.). World Scripture: A Comparative Anthology of Sacred Texts. New York, NY: Paragon House, 1991. ISBN 0892261293

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.