Theory of language

| Linguistics | |

| Comparative linguistics | |

| Computational linguistics | |

| Dialectology | |

| Etymology | |

| Historical linguistics | |

| Morphology | |

| Phonetics | |

| Phonology | |

| Psycholinguistics | |

| Semantics | |

| Synchronic linguistics | |

| Syntax | |

| Psycholinguistics | |

| Sociolinguistics | |

Theory of language is a topic in philosophy of language and theoretical linguistics. The theory of language seeks to understand how language is acquired and used by individuals and communities. Linguists are divided into different schools of thought which generally fall along the lines of the natureânurture debate.

Historically, interest in the theory of language, its origin and purpose dates back to the ancient Greek philosophers. With the advent of the Age of Enlightenment, State of Nature philosophers theorized that individuals created communities and government to ameliorate the conditions of the State of Nature. These individuals needed language in order to communicate with one another.

In the nineteenth century, when sociology was still part of the study of psychology, language was studied as emanating from human psychology and culture, but folk psychology fell out of favor as it became associated with German nationalism. In the twentieth century linguistics became its own field of study as Ferdinand de Saussure established linguistics as separate from psychology. His Course in General Linguistics introduced a new paradigm for the study of linguistics. He introduced concepts such as langue (language) and parole (speech) as well as diachronic v. synchronic linguistics. This approach was foundational for the development of Structuralism, and later Post-structuralism.

In the twentieth century, philosophical approaches approaches beginning with Edmund Husserl led to the development of the school of Analytic philosophy. Ămile Durkheim established sociology as its own discipline and functional explanation, or the adaptation of the social "organism" to its environment, became a popular mode of explanation. Linguists like Roman Jakobson used different linguistic functions to create explanations of the role of language.

With the development of the field of sociobiology, some linguists examined language as a biological entity rather than a humanistic or historical-cultural phenomenon. As in other human and social sciences, theories in linguistics can be divided into humanistic and sociobiological approaches. Theorists often use the same terms, such as "rationalism," "functionalism," "formalism," and "constructionism," with different meanings in different contexts.

Humanistic theories

Humanistic theories consider people as agents in the social construction of language. Language is primarily seen as a sociocultural phenomenon. This tradition emphasizes culture, nurture, and human creativity.[1] A classical rationalist approach to language stems from the philosophy of the Age of Enlightenment. State of Nature theorists like Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued that humans in the State of nature were originally individuals who eventually entered into social relations. Rationalist philosophers argued that people had created language in a step-by-step process to serve their need to communicate with each other. Thus, language is thought of as a rational human invention.[2]

Culturalâhistorical approaches

During the nineteenth century, when sociological questions remained under psychology,[3] languages and language change were thought of as arising from human psychology and the collective unconscious mind of the community, shaped by its history, as argued by Moritz Lazarus, Heymann Steinthal and Wilhelm Wundt.[4] Advocates of VĂślkerpsychologie ('folk psychology') regarded language as Volksgeist; a social phenomenon conceived as the "spirit of the nation."

Wundt claimed that the human mind becomes organized according to the principles of syllogistic reasoning with social progress and education. He argued for a binary-branching model for the description of the mind, and syntax.[5] Folk psychology was imported to North American linguistics by Franz Boas[6] and Leonard Bloomfield who were the founders of a school of thought which was later nicknamed "American structuralism."[7] This framework was not structuralist as it would become understood in the work of Ferdinand de Saussure. It did not consider language as arising from the interaction of meaning and expression. Instead, it was thought that the civilized human mind is organized into binary branching structures. Advocates of this type of structuralism are identified from their use of "philosophical grammar" with its convention of placing the object, but not the subject, into the verb phrase; whereby the structure is disconnected from semantics in sharp contrast to Saussurean structuralism.[8]

Folk psychology became associated with German nationalism,[6] and after World War I Bloomfield apparently replaced Wundt's structural psychology with Albert Paul Weiss's behavioral psychology;[9] although Wundtian notions remained elementary for his linguistic analysis.[10] The Bloomfieldian school of linguistics was eventually reformed as a sociobiological approach by Noam Chomsky (see "generative grammar" below).[8][11]

Structuralism: a sociologicalâsemiotic theory

The study of culture and language developed in a different direction in Europe where Ămile Durkheim successfully separated sociology from psychology, thus establishing it as an autonomous science.[12] Ferdinand de Saussure likewise argued for the autonomy of linguistics from psychology. He created a semiotic theory which would eventually give rise to the movement in human sciences known as structuralism, followed by functionalism or functional structuralism, post-structuralism and other similar tendencies.[13] The names structuralism and functionalism are derived from Durkheim's modification of Herbert Spencer's organicism which draws an analogy between social structures and the organs of an organism, each necessitated by its function.[14][12]

Saussurean linguistics

Saussure approaches the essence of language from two sides. For the one, he borrows ideas from Steinthal[6] and Durkheim, concluding that language is a "social fact." For the other, he creates a theory of language as a system in and for itself which arises from the association of concepts and words or expressions. Thus, language is a dual system of interactive sub-systems: a conceptual system and a system of linguistic forms. Neither of these can exist without the other because, in Saussure's notion, there are no (proper) expressions without meaning, but also no (organized) meaning without words or expressions. Language as a system does not arise from the physical world, but from the contrast between the concepts, and the contrast between the linguistic forms.[15]

In the Cours de linguistique gĂŠnĂŠrale (Course of General Linguistics), Saussure made what became a famous distinction between langue (language) and parole (speech). Language, for Saussure, is the symbolic system through which we communicate. Speech refers to actual utterances. Since we can communicate an infinite number of utterances, it is the system behind them that is important. In separating language from speaking, we are at the same time separating: (1) what is social from what is individual; and (2) what is essential from what is accessory and more or less accidental.

Another key distinction is the relationship between the "signifier" and the "signified." This relationship, the bond between the signifier and signified, is both arbitrary and necessary. It is arbitrary in that there is no inherent relationship between sound and object, between the word "cat" and the animal itself. The principle of arbitrariness dominates all ideas about the structure of language. It makes it possible to separate the signifier and signified, or to change the relationship between them. Based on this distinction, Saussure would argue that language operates based on its own internal logic of differences.

Saussure focused his work on the internal structure of language, studying it synchronically (at a moment in time) versus diachronically as it developed over time. Meaning is created through internal differences within the system of language ("cat" v. "bat.") This structural approach to understanding how meaning in created would become the basis for the development of Structuralism in anthropologists like Claude LĂŠvi-Strauss and later in the work of the post-structuralists like Jacques Derrida.

Logical grammar

Many philosophers of language, since Plato and Aristotle, have considered language as a manmade tool for making statements or propositions about the world on the basis of a predicate-argument structure. Especially in the classical tradition, the purpose of the sentence was considered to be to predicate about the subject. Aristotle's example is "Man is a rational animal," where Man is the subject and is a rational animal is the predicate. It is an attribute of the subject.[16][17]

In the twentieth century, classical logical grammar was defended by Edmund Husserl's "pure logical grammar." Husserl argues, in the spirit of seventeenth-century rational grammar, that the structures of consciousness are compositional and organized into subject-predicate structures. These give rise to the structures of semantics and syntax cross-linguistically.[18] Categorial grammar is another example of logical grammar in the modern context. A categorial grammar consists of two parts: a lexicon, which assigns a set of types (also called categories) to each basic symbol, and some type inference rules, which determine how the type of a string of symbols follows from the types of the constituent symbols. It has the advantage that the type inference rules can be fixed once and for all, so that the specification of a particular language grammar is entirely determined by the lexicon.

More lately, in Donald Davidson's event semantics, for example, the verb serves as the predicate. Like in modern predicate logic, subject and object are arguments of the transitive predicate. A similar solution is found in formal semantics.[19] Many modern philosophers continue to consider language as a logically based tool for expressing the structures of reality by means of predicate-argument structure. This is the position of many philosophers of the Analytic school, such as Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Winfrid Sellars, Hilary Putnam, and John Searle. While continental philosophers pursued traditional metaphysical issues and socio-political-historical dimensions of knowledge, analytic philosophers focused on logical analyses of languages.

Functionalism: language as a tool for communication

There was a shift of focus in sociology in the 1920s, from structural to functional explanation, or the adaptation of the social 'organism' to its environment. Post-Saussurean linguists, led by the Prague linguistic circle, began to study the functional value of the linguistic structure, with communication taken as the primary function of language in the meaning "task" or "purpose." Their work constituted a radical departure from the classical structural position of Ferdinand de Saussure. They suggested that their methods of studying the function of speech sounds could be applied both synchronically, to a language as it exists, and diachronically, to a language as it changes. The functionality of elements of language and the importance of its social function were key aspects of its research program.

These notions translated into an increase of interest in pragmatics, with a discourse perspective (the analysis of full texts) added to the multilayered interactive model of structural linguistics. This gave rise to functional linguistics.[20] Some of its main concepts include information structure and economy.

Roman Jakobson's Language Functions

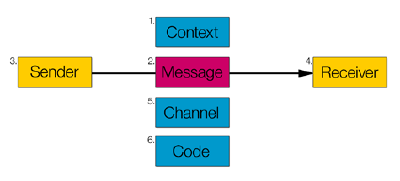

Roman Jakobson, a literary theorist and member of the Prague linguistic circle, claimed that language must be investigated in all the variety of its functions. Before discussing the poetic function, one must define its place among the other functions of language. An outline of those functions demands a concise survey of the constitutive factors in any speech event, in any act of verbal communication.

The Addresser (speaker, author) sends a message (the verbal act, the signifier) to the Addressee (the hearer or reader). To be operative, the message requires a Context (a referent, the signified), seizable by the addresses, and either verbal or capable of being verbalized; a Code (shared mode of discourse, shared language) fully, or at least partially, common to the addresser and the addressee (in other words, to the encoder and decoder of the message); and, finally, a Contact, a physical channel and psychological connection between the addresser and the addressee, enabling both of them to enter and stay in communication. He claims that each of these six factors determines a different function of language.

- the REFERENTIAL function is oriented toward the CONTEXT

- the EMOTIVE (expressive) function is oriented toward the ADDRESSER

- the CONATIVE (action-inducing, such as a command) function is oriented toward the ADDRESSEE

- the METALINGUAL (language speaking about language) function is oriented toward the CODE

- the POETIC function is oriented toward the MESSAGE for its own sake.

One of the six functions is always the dominant function in a text and usually related to the type of text. In poetry, the dominant function is the poetic function: The focus is on the message itself.

The true hallmark of poetry is, according to Jakobson, "âŚthe projection of the principle of equivalence from the axis of selection to the axis of combinationâŚ." Very broadly speaking, it implies that poetry successfully combines and integrates form and function, that poetry turns the poetry of grammar into the grammar of poetry[22]

Formalism: language as a mathematicalâsemiotic system

Structural and formal linguist Louis Hjelmslev considered the systemic organization of the bilateral linguistic system fully mathematical, rejecting the psychological and sociological aspect of linguistics altogether. He considered linguistics as the comparison of the structures of all languages using formal grammars â semantic and discourse structures included.[23] Hjelmslev's idea is sometimes referred to as "formalism."[20] Hjelmslev's sign model is a development of Saussure's bilateral sign model. Saussure considered a sign as having two sides, signifier and signified. Hjelmslev famously renamed signifier and signified as respectively expression plane and content plane, and also distinguished between form and substance. The combinations of the four would distinguish between form of content, form of expression, substance of content, and substance of expression. In Hjelmslev's analysis, a sign is a function between two forms, the content form and the expression form, and this is the starting point of linguistic analysis. However, every sign function is also manifested by two substances: the content substance and the expression substance. The content substance is the physical and conceptual manifestation of the sign. The expression substance is the physical substance in which a sign is manifested. This substance can be sound, as is the case for most known languages, but it can be any material support whatsoever, for instance, hand movements, as is the case for sign languages, or distinctive marks on a suitable medium as in the many different writing systems of the world. Hjelmslev was proposing an open-ended, scientific method of analysis as a new semiotics. In proposing this, he was reacting against the conventional view in phonetics that sounds should be the focus of enquiry.

Post-structuralism: language as a societal tool

The Saussurean idea of language as an interaction of the conceptual system and the expressive system was elaborated in philosophy, anthropology and other fields of human sciences by Claude LĂŠvi-Strauss, Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Julia Kristeva and many others. This movement was interested in the Durkheimian concept of language as a social fact or a rule-based code of conduct; but eventually rejected the structuralist idea that the individual cannot change the norm. Post-structuralists study how language affects our understanding of reality thus serving as a tool of shaping society.[24][25]

Deconstruction

Following the structuralist linguist, Ferdinand de Saussure, Derrida focused on the dichotomy of signifier/signified. Traditional semiotics had viewed linguistics as a stable relationship between referent and the thing. For Saussure, this was only half of the subject matter of linguistics, the "diachronic" relationship of the signifier to the signified. He bracketed this relationship to focus on the "synchronic" relationship of signifier to other signifiers. It is a structuralist approach to language in that Saussure set aside the diachronic relationship to examine how language is structured. Derrida took this a step further. He introduced the concept of diffĂŠrance. The neologism was difference with an "a" in place of the "e." For Derrida it incorporated both Saussure's sense of differing but also included the deferring of meaning. Meaning both differs from itself and meaning is always deferred, unstable. Derrida's approach is designed to dismantle traditional Western metaphysics by exploding the sense of meaning as stable, fixed, universal. Instead, Derrida introduces the notion of "play" in all its various meanings.

Play is introduced in order to undo the whole philosophical tradition which he believes rests on arbitrary dichotomous categories (such as sacred/profane, signifier/signified, mind/body), and that any text contains implicit hierarchies, "by which an order is imposed on reality and by which a subtle repression is exercised, as these hierarchies exclude, subordinate, and hide the various potential meanings."[26] Play means exposing and exploding these hierarchies.

Language as an artificial construct

While the humanistic tradition stemming from nineteenth century VĂślkerpsychologie emphasises the unconscious nature of the social construction of language, some perspectives of post-structuralism and social constructionism regard human languages as man-made rather than natural. At this end of the spectrum, structural linguist Eugenio CoČeriu laid emphasis on the intentional construction of language.[4] Daniel Everett has likewise approached the question of language construction from the point of intentionality and free will.[27]

There were also some contacts between structural linguists and the creators of constructed languages. For example, Saussure's brother RenĂŠ de Saussure was an Esperanto activist, and the French functionalist AndrĂŠ Martinet served as director of the International Auxiliary Language Association. Otto Jespersen created and proposed the international auxiliary language Novial.

Sociobiological theories

In contrast to humanistic linguistics, sociobiological approaches consider language as biological phenomena. Approaches to language as part of cultural evolution can be roughly divided into two main groups: genetic determinism which argues that languages stem from the human genome; and social Darwinism, as envisioned by August Schleicher and Max MĂźller, which applies principles and methods of evolutionary biology to linguistics. Because sociobiogical theories have been labelled as chauvinistic in the past, modern approaches, including Dual inheritance theory and memetics, aim to provide more sustainable solutions to the study of biology's role in language.[28]

Language as a genetically inherited phenomenon

Strong version ('rationalism')

The role of genes in language formation has been discussed and studied extensively. Proposing generative grammar, Noam Chomsky argues that language is fully caused by a random genetic mutation, and that linguistics is the study of universal grammar, or the structure in question.[29] Others, including Ray Jackendoff, point out that the innate language component could be the result of a series of evolutionary adaptations;[30] Steven Pinker argues that, because of these, people are born with a language instinct.

The random and the adaptational approach are sometimes referred to as formalism (or structuralism) and functionalism (or adaptationism), respectively, as a parallel to debates between advocates of structural and functional explanation in biology.[31] Also known as biolinguistics, the study of linguistic structures is parallelized with that of natural formations such as ferromagnetic droplets and botanic forms.[32] This approach became highly controversial at the end of the twentieth century due to a lack of empirical support for genetics as an explanation of linguistic structures.[33][34]

More recent anthropological research aims to avoid genetic determinism. Behavioral ecology and dual inheritance theory, the study of geneâculture co-evolution, emphasize the role of culture as a human invention in shaping the genes, rather than vice versa.[28]

Weak version ('empiricism')

Some former generative grammarians argue that genes may nonetheless have an indirect effect on abstract features of language. This makes up yet another approach referred to as 'functionalism' which makes a weaker claim with respect to genetics. Instead of arguing for a specific innate structure, it is suggested that human physiology and neurological organization may give rise to linguistic phenomena in a more abstract way.[31]

Based on a comparison of structures from multiple languages, John A. Hawkins suggests that the brain, as a syntactic parser, may find it easier to process some word orders than others, thus explaining their prevalence. This theory remains to be confirmed by psycholinguistic studies.[35]

Conceptual metaphor theory from George Lakoff's cognitive linguistics hypothesizes that people have inherited from lower animals the ability for deductive reasoning based on visual thinking, which explains why languages make so much use of visual metaphors.[36][37]

Like in other human and social sciences, theories in linguistics can be divided into humanistic and sociobiological approaches.[38] Some terms, for example 'rationalism', 'functionalism', 'formalism' and 'constructionism', are used with different meanings in different contexts.[39]

Since generative grammar's popularity began to wane towards the end of the twentieth century, there has been a new wave of cultural anthropological approaches to the language question sparking a modern debate on the relationship of language and culture. Participants include Daniel Everett, Jesse Prinz, Nicholas Evans and Stephen Levinson.[27]

Notes

- â Jan Koster, "Theories of language from a critical perspective," in The Cambridge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition eds. Julia Herschensohn and Martha Young-Scholten (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-1139051729), 9â25. Retrieved January 29, 2025.

- â Antoine Arnauld and M. Petitot, "Un Essai sur l'origine et les progès de la language françoise," in Arnauld et Lancelot, Grammaire gĂŠnĂŠrale et raisonnĂŠe de Port-Royal 2nd ed. (Paris, FR: Bossange et Masson, 1810), 1â244.

- â M. Gane, "Durkheim: the sacred language," Economy and Society 12(1)(1983): 1â47.

- â 4.0 4.1 Esa Itkonen, "On Coseriu's legacy" Energeia (III) (2011): 1â29.

- â Pieter Seuren, "Early formalization tendencies in 20th-century American linguistics," in History of the Language Sciences: An International Handbook on the Evolution of the Study of Language from the Beginnings to the Present ed. Sylvain Auroux (Walter de Gruyter, 2008, ISBN 978-3110199826), 2026â2034. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- â 6.0 6.1 6.2 Egbert Klautke, "The mind of the nation: the debate about VĂślkerpsychologie," Central Europe 8(1) (2010):1â19. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- â James P. Blevins, "American descriptivism ('structuralism')," in The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics ed. Keith Allan (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0199585847), 418â437.

- â 8.0 8.1 Pieter A. M. Seuren, Western linguistics: An historical introduction (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 1998, ISBN 0631208917).

- â Maria de Lourdes R. da F. Passos and Maria Matos, "The influence of Bloomfield's linguistics on Skinner," Behav. Anal. 30(2) (2007): 133â151.

- â John E. Joseph, From Whitney to Chomsky: Essays in the History of American Linguistics (Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins, 2002, ISBN 978-9027275370).

- â Steven Johnson, "Sociobiology and you," The Nation November 18, 2002. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- â 12.0 12.1 P. M. Hejl, "The importance of the concepts of "organism" and "evolution" in Emile Durkheim's division of social labor and the influence of Herbert Spencer," in Biology as Society, Society as Biology: Metaphors Sabine Maasen, E. Mendelsohn and P. Weingarted, eds. (Springer, 2013, ISBN 978-9401106733), 155â191.

- â François Dosse, History of Structuralism, Vol.1: The Rising Sign, 1945â1966 trans. Edborah Glassman (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0816622412). Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- â Patrick SĂŠriot, "The Impact of Czech and Russian Biology on the Linguistic Thought of the Prague Linguistic Circle," in Prague Linguistic Circle Papers, Vol. 3 ed. Eva HajiÄovĂĄ, TomĂĄĹĄ Hoskovec, OldĹich LeĹĄka, Petr Sgall, and Zdena SkoumalovĂĄ (John Benjamins, 1999, ISBN 978-9027254436), 15â24.

- â Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics (New York, NY: Philosophy Library, 1959, ISBN 978-0231157278).

- â Pieter A. M. Seuren, Western linguistics: An historical introduction (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 1998, ISBN 0631208917), 250â251.

- â Esa Itkonen, "Philosophy of linguistics," in The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics ed. Keith Allen (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0199585847), 747â775.

- â Wolfe Mays, "Edmund Husserl's Grammar: 100 Years On," JBSP â Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology 33(3) (2002): 317â340.

- â Barbara Partee, "Formal Semantics: Origins, Issues, Early Impact," in The Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication, volume 6 (Manhattan, KS: New Prairie Press, 2011), 1â52. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- â 20.0 20.1 FrantiĹĄek DaneĹĄ, "On Prague school functionalism in linguistics," in Functionalism in Linguistics eds. R. Dirven and V. Fried (Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins, 1987, ISBN 978-9027215246), 3â38.

- â Richard Middleton, Studying Popular Music (Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press, 1990, ISBN 0335152759), 241.

- â Roman Jakobson, "Closing Statements: Linguistics and Poetics," in Style In Language ed. Thomas A. Sebeok, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1960), 350-377.

- â Louis Hjelmslev, Prolegomena to a Theory of Language (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969, ISBN 0299024709).

- â François Dosse, History of Structuralism, Vol.2: The Sign Sets, 1967â Present trans. Edborah Glassman (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1997, ISBN 0816622396).

- â James Williams, Understanding Poststructuralism (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-1844650330).

- â Michele Lamont, "How to Become a Dominant French Philosopher: The Case of Jacques Derrida," American Journal of Sociology 93(3), November 1987, 584â622.

- â 27.0 27.1 Nick J. Enfield, "Language, culture, and mind: trends and standards in the latest pendulum swing," Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 19(10) (2013): 155â169. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- â 28.0 28.1 Tim Lewens, "Cultural Evolution," in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy ed. Edward N. Zalta. Stanford University, May 22, 2023. Retrieved January 22, 2025.

- â Robert C. Berwick and Noam Chomsky, Why Only Us: Language and Evolution (Boston, MA: MIT Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0262034241).

- â Steven Pinker and Ray Jackendoff, "The language faculty: what's special about it?" Cognition 95(2) (2005): 201â236.

- â 31.0 31.1 Margaret Thomas, Formalism and Functionalism in Linguistics: The Engineer and the Collector (Routledge, 2019, ISBN 978-0429455858).

- â Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini and Giuseppe Vitiello, "Linguistics and some aspects of its underlying dynamics," Biolinguistics Volume 9 (2015): 96â115.

- â Marilyn Shatz, "On the development of the field of language development," in Blackwell Handbook of Language Development eds. Hoff and Schatz. (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007, ISBN 978-0470757833), 1â15.

- â Kees de Bot, A History of Applied Linguistics: From 1980 to the Present (London, U.K.: Routledge, 2015, ISBN 978-1138820654).

- â Jae Jung Song, Word Order (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-1139033930).

- â George Lakoff, "Invariance hypothesis: is abstract reasoning based on image-schemas?" Cognitive Linguistics 1(1) (1990): 39â74.

- â George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Philosophy in the Flesh : the Embodied Mind and its Challenge to Western Thought (Basic Books, 1999, ISBN 0465056733.

- â Winfred P. Lehmann "Mellow glory: see language steadily and see it whole," in New Directions in Linguistics and Semiotics ed. James E. Copeland. (John Benjamins, 1984, ISBN 978-9027286437), 17â34.

- â Henning Andersen, "Synchrony, diachrony, and evolution" in Competing Models of Linguistic Change: Evolution and Beyond ed. Ole Nedergaard (Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins, 2006, ISBN 978-9027293190), 59â90.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Andersen, Henning. "Synchrony, diachrony, and evolution" in Competing Models of Linguistic Change: Evolution and Beyond edited by Ole Nedergaard. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins, 2006. ISBN 978-9027293190

- Arnauld, Antoine and M. Petitot. "Un Essai sur l'origine et les progès de la language françoise," in Arnauld et Lancelot, Grammaire gÊnÊrale et raisonnÊe de Port-Royal 2nd ed. Paris, FR: Bossange et Masson, 1810.

- Aronoff, Mark. "Darwinism tested by the science of language," in On Looking into Words (and Beyond): Structures, Relations, Analyses edited by Bowern, Horn and Zanuttini. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2017. ISBN 978-3946234920

- Berwick, Robert C., and Noam Chomsky. Why Only Us: Language and Evolution. Boston, MA: MIT Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0262034241

- Blevins, James P. "American descriptivism ('structuralism')," in The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics edited by Keith Allan. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0199585847

- DaneĹĄ, FrantiĹĄek. "On Prague school functionalism in linguistics," in Functionalism in Linguistics edited by R. Dirven and V. Fried. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins, 1987. ISBN 978-9027215246

- de Bot, Kees. A History of Applied Linguistics: From 1980 to the Present. London, U.K.: Routledge, 2015. ISBN 978-1138820654

- de Saussure, Ferdinand. Course in General Linguistics. New York, NY: Philosophy Library, 1959 (original 1916). ISBN 978-0231157278

- Dosse, François. History of Structuralism, Vol.1: The Rising Sign, 1945â1966 translated by Edborah Glassman. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1997 (original 1991). ISBN 978-0816622412

- Enfield|, Nick J. "Language, culture, and mind: trends and standards in the latest pendulum swing," Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 19(10) (2013): 155â169. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- Gane, M. "Durkheim: the sacred language," Economy and Society 12(1)(1983): 1â47.

- Hejl, P. M. "The importance of the concepts of "organism" and "evolution" in Emile Durkheim's division of social labor and the influence of Herbert Spencer," in Biology as Society, Society as Biology: Metaphors edited by Sabine Maasen, E. Mendelsohn and P. Weingarted. Springer, 2013. ISBN 978-9401106733

- Hjelmslev, Louis. Prolegomena to a Theory of Language. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969 (original 1943). ISBN 0299024709

- Itkonen, Esa. "On Coseriu's legacy" Energeia (III) (2011): 1â29.

- Itkonen, Esa. "Philosophy of linguistics," in The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics edited by Keith Allen. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0199585847

- Jakobson, Roman. "Closing Statements: Linguistics and Poetics," in Style In Language edited by Thomas A. Sebeok. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1960.

- Johnson, Steven. "Sociobiology and you," The Nation. November 18, 2002. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- Joseph, John E. From Whitney to Chomsky: Essays in the History of American Linguistics. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins, 2002. ISBN 978-9027275370

- Klautke, Egbert. "The mind of the nation: the debate about VĂślkerpsychologie," Central Europe 8(1) (2010):1â19. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- Koster, Jan. "Theories of language from a critical perspective,"] in The Cambridge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition edited by Julia Herschensohn and Martha Young-Scholten. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-1139051729

- Lakoff, George. "Invariance hypothesis: is abstract reasoning based on image-schemas?" Cognitive Linguistics 1(1) (1990): 39â74.

- Lamont, Michele. "How to Become a Dominant French Philosopher: The Case of Jacques Derrida," American Journal of Sociology 93(3), November 1987, 584â622.

- Lewens, Tim. "Cultural Evolution," in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy edited by Edward N. Zalta. Stanford University, May 22, 2023. Retrieved January 22, 2025.

- Mays, Wolfe. "Edmund Husserl's Grammar: 100 Years On," JBSP â Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology 33(3) (2002): 317â340.

- Middleton, Richard. Studying Popular Music. Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press, 1990. ISBN 0335152759.

- Partee, Barbara. "Formal Semantics: Origins, Issues, Early Impact," in The Baltic International Yearbook of Cognition, Logic and Communication, volume 6 (Manhattan, KS: New Prairie Press, 2011), 1â52. Retrieved January 20, 2025.

- Passos, Maria de Lourdes R. da F., and Maria Matos. "The influence of Bloomfield's linguistics on Skinner," Behav. Anal. 30(2) (2007): 133â151.

- Piattelli-Palmarini, Massimo and Giuseppe Vitiello. "Linguistics and some aspects of its underlying dynamics," Biolinguistics Volume 9 (2015): 96â115.

- Pinker, Steven, and Ray Jackendoff. "The language faculty: what's special about it?" Cognition 95(2) (2005): 201â236.

- SĂŠriot, Patrick. "The Impact of Czech and Russian Biology on the Linguistic Thought of the Prague Linguistic Circle," in Prague Linguistic Circle Papers, Vol. 3 edited by Eva HajiÄovĂĄ, TomĂĄĹĄ Hoskovec, OldĹich LeĹĄka, Petr Sgall, and Zdena SkoumalovĂĄ. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins, 1999. ISBN 978-9027254436

- Seuren, Pieter A. M. Western linguistics: An historical introduction. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 1998. ISBN 0631208917

- Seuren, Pieter. "Early formalization tendencies in 20th-century American linguistics," in History of the Language Sciences: An International Handbook on the Evolution of the Study of Language from the Beginnings to the Present edited by Sylvain Auroux. Walter de Gruyter, 2008. ISBN 978-3110199826

- Shatz, Marilyn. "On the development of the field of language development," in Blackwell Handbook of Language Development edited by Hoff and Schatz. (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007. ISBN 978-0470757833

- Song, Jae Jung. Word Order. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-1139033930

- Williams, James. Understanding Poststructuralism. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1844650330

| ||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.