Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "Mohandas K. Gandhi" - New World

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

|date_of_death=[[January 30]] [[1948]] | |date_of_death=[[January 30]] [[1948]] | ||

|place_of_death=[[New Delhi]], [[India]]}} | |place_of_death=[[New Delhi]], [[India]]}} | ||

| − | '''Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi''' ([[Devanagari]]: मोहनदास करमचन्द गांधी; [[Gujarati language|Gujarati]]: મોહનદાસ કરમચંદ ગાંધી; [[October 2]] [[1869]] – [[January 30]], [[1948]]) was one of the most important leaders in the fight for freedom in [[India]] and its [[Indian independence movement|struggle for independence]] from the [[British India|British Empire]]. | + | '''Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi''' ([[Devanagari]]: मोहनदास करमचन्द गांधी; [[Gujarati language|Gujarati]]: મોહનદાસ કરમચંદ ગાંધી; [[October 2]] [[1869]] – [[January 30]], [[1948]]) was one of the most important leaders in the fight for freedom in [[India]] and its [[Indian independence movement|struggle for independence]] from the [[British India|British Empire]]. It was his philosophy of “[[Satyagraha]]'' or nonviolent non-compliance (being willing to suffer so that the opponent can realize the error of their ways) — which led India to independence, and has influenced social reformers around the world, including [[ Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.]] and the [[American civil rights movement]], [[Steve Biko]] and the freedom struggles in [[South Africa]], and [[Aung San Suu Kyi]] in [[Myanmar]]. |

| − | + | ||

| + | As a member of a privileged, and wealthy family, he studied law in England at the turn of the 20th century, and subsequently pursued a legal career in South Africa. But it was his role as a social reformer than came to dominate his thinking and actions. In South Africa he successfully led the Indian community to protest discriminatory laws and situations. In India, he campaigned to eliminate outdated Hindu customs, such as satee, dowry, and the condition of the untouchables. He led poor farmers in a reform movement in Bihar and Gujarat. On a national level, he led thousands of Indians on the well-known [[Salt Satyagraha|Dandi Salt March]], a nonviolent resistance to a British tax. As a member and leader of the [[Indian National Congress]], he led a nationwide, nonviolent campaign calling on the British to ''[[Quit India]]''. In each case, the British government found itself face to face with a formidable opponent, one to whom, in most cases, they ceded. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The strength of his convictions came from his own moral purity: he made his own clothes - the traditional Indian [[dhoti]] and shawl, and lived on a simple [[vegetarian]] diet. He took a vow of sexual abstinence at a relatively early age and used rigorous [[fasts]] - abstaining from food and water for long periods - for self-purification as well as a means for protest. Born a Hindu of the ''[[vaishya]]'' or business, [[caste]], he came to value all religion, stating that he found all religions to be true; all religions to have some error; and all religions to be “almost as dear to me as my own.” <ref> M. Gandhi, ‘’All Men are Brothers’’, pp54 </ref> He believed in an unseen power and moral order that transcends and harmonizes all people. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gandhi was equally devoted to people, rejecting all caste, class and race distinctions. In truth, it was probably the power of his conscience and his compassion for others that moved him to greatness. He is commonly known both in India and elsewhere as “Mahatma Gandhi,” a [[Sanskrit]] title meaning “Great Soul” given to him in recognition of his sincere efforts to better the lives of others, and his own humble lifestyle. In India he is also fondly called ''Bapu'', which in many [[languages of India|Indian languages]] means ''Father''. In India, his birthday, October 2, is commemorated each year as '''Gandhi Jayanti''', and is a [[holidays in India|national holiday]]. | ||

| − | |||

Revision as of 23:37, 13 September 2006

- "Gandhi" redirects here.

| Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi |

|---|

India's "Father of the nation" —Mahatma Gandhi

|

| Born |

| October 2 1869 Porbandar, Gujarat, India |

| Died |

| January 30 1948 New Delhi, India |

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (Devanagari: मोहनदास करमचन्द गांधी; Gujarati: મોહનદાસ કરમચંદ ગાંધી; October 2 1869 – January 30, 1948) was one of the most important leaders in the fight for freedom in India and its struggle for independence from the British Empire. It was his philosophy of “Satyagraha or nonviolent non-compliance (being willing to suffer so that the opponent can realize the error of their ways) — which led India to independence, and has influenced social reformers around the world, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the American civil rights movement, Steve Biko and the freedom struggles in South Africa, and Aung San Suu Kyi in Myanmar.

As a member of a privileged, and wealthy family, he studied law in England at the turn of the 20th century, and subsequently pursued a legal career in South Africa. But it was his role as a social reformer than came to dominate his thinking and actions. In South Africa he successfully led the Indian community to protest discriminatory laws and situations. In India, he campaigned to eliminate outdated Hindu customs, such as satee, dowry, and the condition of the untouchables. He led poor farmers in a reform movement in Bihar and Gujarat. On a national level, he led thousands of Indians on the well-known Dandi Salt March, a nonviolent resistance to a British tax. As a member and leader of the Indian National Congress, he led a nationwide, nonviolent campaign calling on the British to Quit India. In each case, the British government found itself face to face with a formidable opponent, one to whom, in most cases, they ceded.

The strength of his convictions came from his own moral purity: he made his own clothes - the traditional Indian dhoti and shawl, and lived on a simple vegetarian diet. He took a vow of sexual abstinence at a relatively early age and used rigorous fasts - abstaining from food and water for long periods - for self-purification as well as a means for protest. Born a Hindu of the vaishya or business, caste, he came to value all religion, stating that he found all religions to be true; all religions to have some error; and all religions to be “almost as dear to me as my own.” [1] He believed in an unseen power and moral order that transcends and harmonizes all people.

Gandhi was equally devoted to people, rejecting all caste, class and race distinctions. In truth, it was probably the power of his conscience and his compassion for others that moved him to greatness. He is commonly known both in India and elsewhere as “Mahatma Gandhi,” a Sanskrit title meaning “Great Soul” given to him in recognition of his sincere efforts to better the lives of others, and his own humble lifestyle. In India he is also fondly called Bapu, which in many Indian languages means Father. In India, his birthday, October 2, is commemorated each year as Gandhi Jayanti, and is a national holiday.

Early Life

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born into a Hindu Modh family of the vaishya, or business, caste in Porbandar, Gujarat, India in 1869. His father, Karamchand Gandhi, was the diwan or chief minister of Porbandar under the British – a position earlier held by his grandfather. His mother, Putlibai, was a devout Hindu of the Pranami Vaishnava order, and Karamchand's fourth wife. His father’s first two wives each died (presumably in childbirth) after bearing him a daughter, and the third was incapacitated and gave his father permission to marry again. Gandhi grew up surrounded by the Jain influences common to Gujarat, so learned from an early age the meaning of ahimsa (non-injury to living thing), vegetarianism, fasting for self-purification, and a tolerance for members of other creeds and sects. At the age of 13 (May 1883), by his parents’ arrangement, Gandhi married Kasturba Makhanji (also spelled "Kasturbai" or known as "Ba"), who was the same age as he. They had four sons: Harilal Gandhi, born in 1888; Manilal Gandhi, born in 1892; Ramdas Gandhi, born in 1897; and Devdas Gandhi, born in 1900. Gandhi continued his studies after marriage, but was a mediocre student at Porbandar and later Rajkot. He barely passed the matriculation exam for Samaldas College at Bhavnagar, Gujarat in 1887. He was unhappy at college, because his family wanted him to become a barrister. He leapt at the opportunity to study in England, which he viewed as "a land of philosophers and poets, the very centre of civilization."

At the age of 18 on September 4, 1888, Gandhi set sail for London to train as a barrister at the University College London Prior to leaving India, he made a vow to his mother, in the presence of a Jain monk Becharji, the he would observe the Hindu abstinence of meat, alcohol, and promiscuity. He kept his vow on all accounts. English boiled vegetables were distasteful to Gandhi, so he often went without eating, as he was too polite to ask for other food. When his friends complained he was too clumsy for decent society because of his refusal to eat meat, he determined to compensate by becoming an English gentleman in other ways. This determination led to a brief experiment with dancing. By chance he found one of London's few vegetarian restaurants and a book on Vegetarianism which increased his devotion to the Hindu diet. He joined the Vegetarian Society, was elected to its executive committee, and founded a local chapter. He later credited this with giving him valuable experience in organizing institutions.

While in London Gandhi rediscovered other aspects of the Hindu religion as well. Two members of the Theosophical Society (a group founded in 1875 to further universal brotherhood through the study of Buddhist and Hindu Brahmanistic literature) encouraged him to read the classic writings of Hinduism. This whetted his appetite for learning about religion, and he studied other religions as well - Christianity, Buddhism and Islam. He returned to India after being admitted to the bar of England and Wales. His readjustment to Indian life was difficult due to the fact that his mother had died while he was away (his father died shortly before he left for England), and because some of his extended family shunned him – believing that a foreign voyage had made him unclean and was sufficient cause to excommunicate him from their caste. After six months of limited success in Bombay (Mumbai) establishing a law practice, Gandhi returned to Rajkot to earn a modest living drafting petitions for litigants. After an incident with a British officer, he was forced to close down that business as well. In his autobiography, he describes this incident as a kind of unsuccessful lobbying attempt on behalf of his older brother. It was at this point (1893) that he accepted a year-long contract from an Indian firm to a post in Natal, South Africa.

Civil rights movement in South Africa (1893–1914)

Gandhi, a young lawyer, was a mild-mannered, diffident and politically indifferent. He had read his first newspaper at the age of 18, and was prone to stage fright while speaking in court. The discrimination commonly directed at blacks and Indians in South Africa changed him dramatically. Two incidents are particularly notable. In court in the city of Durban, shortly after arriving in South Africa, Gandhi was asked by a magistrate to remove his turban. Gandhi refused, and subsequently stormed out of the courtroom. Not long after that he was thrown off a train at Pietermaritzburg for refusing to ride in the third class compartment while holding a valid first class ticket. Later, on the same journey, a stagecoach driver beat him for refusing to make room for a European passenger by standing on the footboard. Finally, he was barred from several hotels because of his race. This experience of racism, prejudice and injustice became a catalyst for his later activism. The moral indignation he felt led him to organize the Indian community to improve their situation.

At the end of his contract, preparing to return to India, Gandhi learned about a bill before the Natal Legislative Assembly that if passed, would deny Indians in South Africa the right to vote. His South African friends lamented that they could not oppose the bill because they did not have the necessary expertise. Gandhi stayed and thus began the “History of Satyagraha” in South Africa. He circulated petitions to the Natal Legislature and to the British Government opposing the bill. Though unable to halt the bill's passage, his campaign drew attention to the grievances of Indians in South Africa. Supporters convinced him to remain in Durban to continue fighting against the injustices they faced. Gandhi founded the Natal Indian Congress in 1894, with himself as the Secretary and used this organization to mold the Indian community of South Africa into a heterogeneous political force. He published documents detailing their grievances along with evidence of British discrimination in South Africa.

In 1896, Gandhi returned briefly to India to bring his wife and children to live with him in South Africa. While in India he reported the discrimination faced by Indian residents in South Africa to the newspapers and politicians in India. An abbreviated form of his account found its way into the papers in Britain and finally in South Africa. As a result, when he returned to Natal in January 1897, a group of angry white South African residents were waiting to lynch him. His personal values were evident at that stage: he refused to press charges on any member of the group, stating that it was one of his principles not to seek redress for a personal wrong in a court of law.

Gandhi opposed the British policies in South Africa, but supported the government during the Boer War in 1899. Gandhi argued that support for the British legitimized Indian demands for citizenship rights as members of the Empire. But his volunteer ambulance corps of 300 free Indians and 800 indentured laborers (the 'Indian Ambulance Corps), unlike most other medical units, served wounded black South Africans. He was decorated for his work as stretcher-bearer during the Battle of Spion Kop. In 1901, he Considered his work in South Africa to be done, and set up a trust fund for the Indian community with the farewell gifts given to him and his family. It took some convincing for his wife to agree to give up the gold necklace which according to Gandhi did not go with their new, simplified lifestyle. They returned to India, but promised to return if the need arose. In India Gandhi again informed the Indian Congress and other politicians about events in South Africa.

At the conclusion of the war the situation in South Africa deteriorated and Gandhi was called back in late 1902. In 1906, the Transvaal government required that members of the Indian community be registered with the government. At a mass protest meeting in Johannesburg, Gandhi, for the first time, called on his fellow Indians to defy the new law rather than resist it through violent means. The adoption of this plan led to a seven-year struggle in which thousands of Indians were jailed (including Gandhi on many occasions), flogged, or even shot, for striking, refusing to register, burning their registration cards, or engaging in other forms of non-violent resistance. The public outcry over the harsh methods of the South African government in response to the peaceful Indian protesters finally forced South African General Jan Christian Smuts to negotiate a compromise with Gandhi.

This method of Satyagraha (devotion to the truth), or non-violent protest, grew out of his spiritual quest and his search for a better society. He came to respect all religions, incorporating the best qualities into his own thought. Instead of doctrine, the guide to his life was the inner voice that he found painful to ignore, and his sympathy and love for all people. Rather than hatred, he advocated helping the opponent realize their error through patience, sympathy and, if necessary, self-suffering. He often fasted in penance for the harm done by others. He was impressed with John Ruskin’s ideas of social reform (Unto This Last) and with Tolstoy’s ideal of communal harmony (The Kingdom of God is Within You). He sought to emulate these ideals in his two communal farms – Phoenix colony near Durban and Tolstoy farm near Johannesburg. Residents grew their own food and everyone, regardless of caste, race or religion, was equal. He published a popular weekly paper, Indian Opinion, from Phoenix, which gave him an outlet for his developing philosophy. He gave up his law practice. Devotion to community service had led him to a vow of brahmacharya in 1906. Thereafter, he denied himself worldly and fleshly pleasures, including rich food, sex (his wife agreed), family possessions, and the safety of an insurance policy. Striving for purity of thought, he later challenged himself against sexual arousal by close association with attractive women – an action severely criticized by modern Indian cynics who doubt his success in that area.

Fighting for Indian Independence (1916–1945)

Gandhi and his family returned to India in 1915, where he was called the “Great Soul (‘’Mahatma’’) in beggar’s garb” by Rabindranath Tagore. [2]In May of the same year he founded the Satyagrah Ashram on the outskirts of Ahmedabad with 25 men and women who took vows of truth, celibacy, ahimsa, nonpossession, control of the palate, and service of the Indian people. He sought to improve Hinduism by eliminating untouchability and other outdated customs. As he had done in South Africa, Gandhi urged support of the British during World War I and actively encouraged Indians to join the army, reasoning again that if Indians wanted full citizenship rights of the Empire, they must help in its defense. His rationale was opposed by many. His involvement in Indian politics was mainly through conventions of the Indian National Congress, and his association with Gopal Krishna Gokhale, one of most respected leaders of the Congress Party at that time.

Champaran and Kheda

Gandhi first used his ideas of Satyagraha in India on a local level in 1918 in Champaran, a district in the state of Bihar, and in Kheda in the state of Gujarat. In both states he organized civil resistance on the part of tens of thousands of landless farmers and poor farmers with small lands, who were forced to grow indigo and other cash crops instead of the food crops necessary for their survival. It was an area of extreme poverty, unhygienic villages, rampant alcoholism and untouchables. In addition to the crop growing restrictions, the British had levied an oppressive tax. Gandhi’s solution was to establish an ashram near Kheda, where scores of supporters and volunteers from the region did a detailed study of the villages - itemizing atrocities, suffering and degenerate living conditions. He led the villagers in a clean up movement, encouraging social reform, and building schools and hospitals. For his efforts Gandhi arrested by police on the charges of unrest and was ordered to leave Bihar. Hundreds of thousands of people protested and rallied outside the jail, police stations and courts demanding his release, which was unwillingly granted. Gandhi then organized protests and strikes against the landlords, who finally agreed to more pay and allowed the farmers to determine what crops to raise. The government cancelled tax collections until the famine ended. Gandhi’s associate, Sardar Vallabhai Patel represented the farmers in negotiations with the British in Kheda, where revenue collection was suspended and prisoners were released. The success in these situations spread throughout the country. It was during this time that Gandhi began to be addressed as Bapu (Father) and Mahatma.

Non-Cooperation

Gandhi used Satyagraha on a national level in 1919, the year the Rowlatt Act was passed, allowing the government to imprison persons accused of sedition without trial. Also that year, in Punjab, 1-2,000 people were wounded and 400 or more were killed by British troops in the Amritsar massacre. [3] A traumatized and angry nation engaged in retaliatory acts of violence against the British. Gandhi criticized both the British and the Indians. Arguing that all violence was evil and could not be justified, he convinced the national party to pass a resolution offering condolences to British victims and condemning the Indian riots.[4] At the same time, these incidents led Gandhi to focus on complete self-government and complete control of all government institutions. This matured into Swaraj or complete individual, spiritual, political independence.

In 1921, the Indian National Congress invested Gandhi with executive authority. Under his leadership, the party was transformed from an elite organization to one of mass national appeal and membership was opened to anyone who paid a token fee. Congress was reorganized (including a hierarchy of committees), got a new constitution and the goal of Swaraj. Gandhi’s platform included a swadeshi policy – the boycott of foreign-made (British) goods. Instead of foreign textiles, he advocated the use of khadi (homespun cloth), and spinning to be done by all Indian men and women, rich or poor, to support the independence movement.[5] Gandhi’s hope was that this would encourage discipline and dedication in the freedom movement and weed out the unwilling and ambitious. It was also a clever way to include women in political activities generally considered unsuitable for them. Gandhi had urged the boycott of all things British, including educational institutions, law courts, government employment, British titles and honours. He himself returned an award for distinguished humanitarian work he received in South Africa. Others renounced titles and honors, there were bonfires of foreign cloth, lawyers resigned, students left school, urban residents went to the villages to encourage non violent non-cooperation. [6]

This platform of "non-cooperation" enjoyed wide-spread appeal and success, increasing excitement and participation from all strata of Indian society. Yet just as the movement reached its apex, it ended abruptly as a result of a violent clash in the town of Chauri Chaura, Uttar Pradesh, in February 1922, resulting in the death of a policeman. Fearing that the movement would become violent, and convinced that his ideas were misunderstood, Gandhi called off the campaign of mass civil disobedience.[7] He was arrested on March 10, 1922, tried for sedition, and sentenced to six years in prison. After serving nearly two years, he was released (February 1924) after an operation for appendicitis. Meantime, without Gandhi, the Indian National Congress had split into two factions. Chitta Ranjan Das and Motilal Nehru broke with the leadership of Chakravarti Rajagopalachari and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel in the National Congress Party to form the Swaraj Party. Furthermore, cooperation among Hindus and Muslims, which had been strong during the nonviolence campaign, was breaking down. Gandhi attempted to bridge these differences through many means, including a twenty-one day fast for Hindu-Muslim unity in the autumn of 1924, but with limited success.[8]

Swaraj and the Salt Satyagraha

- Main articles: Simon Commission, Nehru Report and Salt Satyagraha

For the next several years, Gandhi worked behind the scenes to resolve the differences between the Swaraj Party and the Indian National Congress. He also expanded his initiatives against untouchability, alcoholism, ignorance and poverty. In 1927 a constitutional reform commission was appointed under Sir John Simon. Because it did not include a single Indian, it was successfully boycotted by both Indian political parties. A resolution was passed at the Calcutta Congress, December 1928, calling on Britain to grant India dominion status or face a new campaign of non-violence with complete independence as the goal. Indian politicians disagreed about how long to give the British. Younger leaders Subhas Chandra Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru called for immediate independence, whereas Gandhi wanted to allow two years. They settled on a one year wait. [9] In October, 1929, Lord Irwin revealed plans for a Round Table conference between the British and the Indian representatives, but when asked if its purpose was to establish dominion status for India, he would give no such assurances. The Indian politicians had their answer. On December 31, 1929, the flag of India was unfurled in Lahore. On January 26, 1930 millions of Indians pledged complete independence at Gandhi’s request. The day is still celebrated as India's Independence Day.

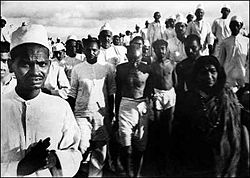

The first move in the Swaraj non-violent campaign was the famous Salt March. The government monopolized the salt trade, making it illegal for anyone else to produce it, even though it was readily available to those near the sea coast. Because the tax on salt affected everyone, it was a good focal point for protest. Gandhi marched 400 kilometres (248 miles) from Ahmedabad to Dandi, Gujarat to make his own salt near the sea. In the 23 days (March 12 to April 6) it took, the march gathered thousands. Once in Dandi, Gandhi encouraged everyone to make and trade salt. In the next days and weeks, thousands made or bought illegal salt, and by the end of the month, more than 60,000 had been arrested. It was one of his most successful campaigns. He was arrested and imprisoned in May.

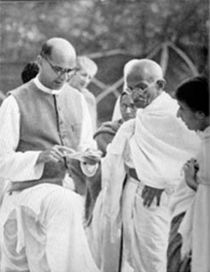

Recognizing his influence on the Indian people, the government, represented by Lord Irwin, decided to negotiate with Gandhi. The Gandhi-Irwin Pact, signed on March 1931, suspended the civil disobedience movement in return for freeing all political prisoners, including those from the salt march, and allowing salt production for personal use. As the sole representative of the Indian National Congress, Gandhi was invited to attend a Round Table Conference in London, but was disappointed to find it focused on Indian minorities (mainly Muslims) rather than the transfer of power. Gandhi and the nationalists faced a new campaign of repression under Lord Irwin's successor, Lord Willingdon. Six days after returning from England, Gandhi was arrested and isolated from his followers in an unsuccessful attempt to destroy his influence. Meanwhile, the British government proposed segregation of the untouchables as a separate electorate. Gandhi objected, and embarked on a fast to death to procure a more equitable arrangement for the Harijans. On the 6th day of his fast, the government agreed to abandon the idea of a separate electorate. This began a campaign by Gandhi to improve the lives of the untouchables, whom he named Harijans, the children of God. On May 8, 1933 Gandhi began a 21-day fast of self-purification to help the Harijan movement.[10] In 1933 he started a weekly publication, the Harijan, through which he made public his thoughts to the Indian people all the rest of his life. In the summer of 1934, three unsuccessful attempts were made on his life.

Gandhi resigned as leader and member from the Congress party in 1934, convinced that it had adopted his ideas of nonviolence as a political strategy rather than a as a fundamental life principle. His resignation encouraged wider participation among communists, socialists, trade unionists, students, religious conservatives, persons with pro-business convictions. [11] He returned to head the party in 1936, in the Lucknow session of Congress with Nehru as president. Gandhi wanted the party to focus on winning independence, but he did not interfere when it focused voted to approve socialism as its goal in post-independence. But he clashed with Subhas Bose, who was elected president in 1938, and opposed Gandhi’s platforms of democracy and of non-violence. Despite their differences and Gandhi’s criticism, Bose won a second term, but left soon after when the All-India leaders resigned en masse in protest of his abandonment of principles introduced by Gandhi.[12]

World War II and Quit India

When World War II broke out in 1939, Gandhi was initially in favor of "non-violent moral support" for the British. Other Congress leaders, however, were offended that the viceroy had committed India in the war effort without consultation, and resigned en masse. [13] After lengthy deliberations, Indian politicians agreed to cooperate with the British government in exchange for complete independence. The viceroy refused, and Congress called on Gandhi to lead them. On August 8, 1942, Congress passed a “Quit India” resolution, which became the most important move in the struggle for independence. There were mass arrests and violence on an unprecedented scale.[14] Thousands of freedom fighters were killed or injured in police firing, and hundreds of thousands were arrested. Gandhi clarified that this time the movement would not be stopped if individual acts of violence were committed, saying that the "ordered anarchy" around him was "worse than real anarchy". He called on all Congressmen and Indians to maintain discipline in ahimsa, and Karo Ya Maro (Do or Die) in the cause of ultimate freedom.

Gandhi and the entire Congress Working Committee were arrested in Bombay (Mumbai) by the British on August 9, 1942. Gandhi was held for two years in the Aga Khan Palace in Pune. Although the ruthless suppression of the movement by British forces brought relative order to India by the end of 1943, Quit India succeeded in its objective. At the end of the war, the British gave clear indications that power would be transferred to Indian hands, and Gandhi called off the struggle, and the Congress leadership and around 100,000 political prisoners were released. During his time in prison, Gandhi's health had deteriorated, however, and he suffered two terrible blows in his personal life. In February 1944, his wife Kasturba died in prison, and just a few months earlier Mahadev Desai, his 42-year old secretary died of a heart attack. Six weeks after his wife’s death, Gandhi suffered a severe malaria attack. He was released before the end of the war because of his failing health and necessary surgery; the British did not want him to die in prison and enrage the entire nation beyond control.

Freedom and partition of India

In March of 1946, the British Cabinet Mission recommended complete withdrawal of the British from India, and the formation of one federal Indian government. But when the Muslim League withdrew its support for the proposal, and lobbied for separation, it became the basis of a partition policy. Gandhi was vehemently opposed to any plan that divided India into two separate countries. Muslims had lived side by side with Hindus and Sikhs for many years. But Jinnah commanded widespread support in West Punjab, Sindh, NWFP and East Bengal. Congress leaders, Nehru and Patel, both realized that control would go to the Muslim League if the Congress did not approve the plan. But they needed Gandhi’s agreement. Even his closest colleagues accepted partition as the best way out. A devastated Gandhi finally gave his assent, and the partition plan was approved by the Congress leadership as the only way to prevent a wide-scale Hindu-Muslim civil war.

Gandhi called partition “a spiritual tragedy.” On the day of the transfer of power (August 15, 1947), Gandhi mourned alone in Calcutta, where he had been working to end the city’s communal violence. When fresh violence broke out there a few weeks later, he vowed to fast to death unless the killing stopped. All parties pledged to stop. He also conducted extensive dialogue with Muslim and Hindu community leaders, working to cool passions in northern India, as well. Despite the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, he was troubled when the Government decided to deny Pakistan the Rs. 55 crores due as per agreements made by the Partition Council. Leaders like Sardar Patel feared that Pakistan would use the money to bankroll the war against India. Gandhi was also devastated when demands resurged for all Muslims to be deported to Pakistan, and when Muslim and Hindu leaders expressed frustration and an inability to come to terms with one another.[15] He launched his last fast-unto-death in Delhi, asking that all communal violence be ended once and for all, and that the payment of Rs. 55 crores be made to Pakistan. Gandhi feared that instability and insecurity in Pakistan would increase their anger against India, and violence would spread across the borders. He further feared that Hindus and Muslims would renew their enmity and precipitate into an open civil war. After emotional debates with his life-long colleagues, Gandhi refused to budge, and the Government rescinded its policy and made the payment to Pakistan. Hindu, Muslim and Sikh community leaders, including the RSS and Hindu Mahasabha assured him that they would renounce violence and call for peace. Gandhi thus broke his fast by sipping orange juice.[16]

Assassination

On January 30, 1948, on his way to a prayer meeting, Gandhi was shot dead in Birla House, New Delhi, by Nathuram Godse. Godse was a Hindu radical with links to the extremist Hindu Mahasabha, who held Gandhi responsible for weakening India by insisting upon a payment to Pakistan.[17] Godse and his co-conspirator Narayan Apte were later tried and convicted, and on 15 November, 1949, were executed. A prominent revolutionary and Hindu extremist, the president of the Mahasabha, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was accused of being the architect of the plot, but was acquitted due to lack of evidence. Gandhi's memorial (or Samādhi) at Rāj Ghāt, New Delhi, bears the epigraph, (Devanagiri: हे ! राम or, Hé Rām), which may be translated as "Oh God". These are widely believed to be Gandhi's last words after he was shot at, though the veracity of this statement has been disputed by many.[18] Jawaharlal Nehru addressed the nation through radio:

- "Friends and comrades, the light has gone out of our lives, and there is darkness everywhere, and I do not quite know what to tell you or how to say it. Our beloved leader, Bapu as we called him, the father of the nation, is no more. Perhaps I am wrong to say that; nevertheless, we will not see him again, as we have seen him for these many years, we will not run to him for advice or seek solace from him, and that is a terrible blow, not for me only, but for millions and millions in this country."

Gandhi's principles

Truth

Gandhi dedicated his life to the wider purpose of discovering truth, or Satya. He tried to achieve this by learning from his own mistakes and conducting experiments on himself. He named his autobiography The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Gandhi found that uncovering the truth was not always popular as many people were resistant to change, preferring instead to maintain the existing status quo because of either inertia, self-interest or misguided beliefs. However he also discovered that once the truth was on the march nothing could stop it. All it took was time to achieve traction and gain momentum. As Gandhi said:

- "The Truth is far more powerful than any weapon of mass destruction".

Gandhi said that the most important battle to fight was in overcoming his own demons, fears and insecurities. He thought it was all too easy to blame people, governing powers or enemies for his personal actions and well-being. He noted the solution to problems could normally be found just by looking in the mirror. One of the greatest contributions of Mahatma Gandhi was in the realm of ontology and its association with truth. For Gandhi, "to be" did not mean to exist within the realm of time, as it has in the past with the Greek philosophers. But rather, "to exist" meant to exist within the realm of truth, or to use the term Gandhi did, satya. Gandhi summarized his beliefs first when he said "God is Truth," but as typical of Gandhi, he evolved, later to correct himself and state that "Truth is God." The first statement seemed insufficient to Gandhi, as the mistake could be made that Gandhi was using Truth as a description of God, rather than the summative definition of the entire essence of God. Satya (Truth) in Gandhi's philosophy IS God. It shares all the characteristics of the Hindu concept of God, or Brahman. It lives within us, that little voice that tells us the right thing to do, but also guides the universe.

Nonviolence

The concept of nonviolence (ahimsa) and nonresistance has a long history in Indian religious thought and has had many revivals in Hindu, Buddhist, Jain and Christian contexts. Gandhi explains his philosophy and way of life in his autobiography The Story of My Experiments with Truth. He was quoted as saying:

- "When I despair, I remember that all through history the way of truth and love has always won. There have been tyrants and murderers and for a time they seem invincible, but in the end, they always fall — think of it, ALWAYS."

- "What difference does it make to the dead, the orphans, and the homeless, whether the mad destruction is wrought under the name of totalitarianism or the holy name of liberty and democracy?"

- "An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind".

- "There are many causes that I am prepared to die for but no causes that I am prepared to kill for".

In applying these principles, Gandhi did not balk from taking them to their most logical extremes. In 1940, when invasion of the British Isles by Nazi Germany looked imminent, Gandhi offered the following advice to the British people (Non-Violence in Peace and War):

- "I would like you to lay down the arms you have as being useless for saving you or humanity. You will invite Herr Hitler and Signor Mussolini to take what they want of the countries you call your possessions.... If these gentlemen choose to occupy your homes, you will vacate them. If they do not give you free passage out, you will allow yourselves, man, woman, and child, to be slaughtered, but you will refuse to owe allegiance to them".

Even in 1946, by which time Gandhi had learned of The Holocaust, he said to biographer Louis Fisher:[19]

- "The Jews should have offered themselves to the butcher's knife. They should have thrown themselves into the sea from cliffs."

However, Gandhi was aware that this level of nonviolence required incredible faith and courage, which he realized everyone did not possess. He therefore advised that everyone need not keep to nonviolence, especially if it was used as a cover for cowardice:

- "Gandhi guarded against attracting to his satyagraha movement those who feared to take up arms or felt themselves incapable of resistance. 'I do believe,' he wrote, 'that where there is only a choice between cowardice and violence, I would advise violence.' "[20]

- "At every meeting I repeated the warning that unless they felt that in non-violence they had come into possession of a force infinitely superior to the one they had and in the use of which they were adept, they should have nothing to do with non-violence and resume the arms they possessed before. It must never be said of the Khudai Khidmatgars that once so brave, they had become or been made cowards under Badshah Khan's influence. Their bravery consisted not in being good marksmen but in defying death and being ever ready to bear their breasts to the bullets."[21]

Vegetarianism

As a young child, Gandhi experimented in meat-eating. This was due partially to his inherent curiosity as well as his rather persuasive peer and friend Sheikh Mehtab. The idea of vegetarianism is deeply engrained in Hindu and Jain traditions in India, and, in his native land of Gujarat, most Hindus were vegetarian. The Gandhi family was no exception. Before leaving for his studies in London, Gandhi made a promise to his mother, Putlibai and his uncle, Becharji Swami that he would abstain from eating meat, taking alcohol, and engaging in promiscuity. He held fast to his promise and gained more than a diet, he gained a basis for his life-long philosophies. As Gandhi grew into adulthood, he became a strict vegetarian. He wrote articles on the subject, some of which were published in the London Vegetarian Society's publication: "The Vegetarian." Gandhi became inspired by many great minds during this period and befriended a chairman of the London Vegetarian Society, Dr. Oldfield.

Having also read and admired the work of Henry Stephens Salt, the young Mohandas metand often corresponded with the vegetarian campaigner. Gandhi spent much time advocating vegetarianism during and after his time in London. To Gandhi, a vegetarian diet would not only satisfy the requirements of the body, it would also serve an economic purpose as meat was/is generally more expensive than grains, legumes, and fruits.Also, many Indians of the time struggled with low income, thus vegetarianism was seen not only as a spiritual practice but also a practical one. However staunch in his diet Gandhi did, on occasion, make allowances in his habits depending health issues. He refers to eating table eggs in his 1948 article Key to Health.[22] He abstained from eating for long periods, using fasting as a political weapon. He refused to eat until his death or his demands were met. It was noted in his autobiography that vegetarianism was the beginning of his deep commitment to Brahmacharya; without total control of the pallet his success in Bramacharya would have been likely to falter.

Brahmacharya

Gandhi gave up sexual intercourse at the age of 36, becoming totally celibate while still married. This decision was deeply influenced by the philosophy of brahmacharya—spiritual and practical purity—largely associated with celibacy and asceticism. Gandhi saw brahmacharya as a means of going close to God and as a primary foundation for self realisation. In his autobiography he tells of his battle against lustful urges and fits of jealousy with his childhood bride, Kasturba. He felt it his personal obligation to remain celibate so that he could learn to love, rather than lust. For Gandhi brahmacharya meant control of the senses in thought, word and deed.[23]

Simplicity

Gandhi earnestly believed that a person involved in social service should lead a simple life. His simplicity began by renouncing the western lifestyle he was leading in South Africa. Gandhi reduced his expenditure by embracing a simple lifestyle, which included washing his own clothes.[24] On one occasion he returned the gifts bestowed to him from the natals for his diligent service to the community.[25]

Gandhi spent one day of each week in silence. He believed that abstaining from speaking brought him inner peace. This influence was drawn from the Hindu principles of mouna (silence) and shanti (peace). On such days he communicated with others by writing on paper. For three and a half years, from the age of 37, Gandhi refused to read newspapers, claiming that the tumultuous state of world affairs caused him more confusion than his own inner unrest. Returning to India from South Africa, where he had enjoyed a successful legal practice, he gave up wearing Western-style clothing, which he associated with wealth and success. He dressed to be accepted by the poorest person in India, advocating the use of homespun cloth (khadi). Gandhi and his followers adopted the practice of weaving their own clothes from thread they themselves spun, and encouraged others to do so. While Indian workers were often idle due to unemployment, they had often bought their clothing from industrial manufacturers owned by British interests. It was Gandhi's view that if Indians made their own clothes, it would deal an economic blow to the British establishment in India. Consequently, the spinning wheel was later incorporated into the flag of the Indian National Congress.

Faith

Gandhi was born a Hindu and was a practicing Hindu all his life, deriving most of his principles from Hinduism. As a common Hindu, he believed all religions to be equal, and rejected all efforts to convert him to a different faith. He was an excellent theologist and read extensively about all major religions. He had the following to say about Hinduism:

- "Hinduism as I know it entirely satisfies my soul, fills my whole being ... When doubts haunt me, when disappointments stare me in the face, and when I see not one ray of light on the horizon, I turn to the Bhagavad Gita, and find a verse to comfort me; and I immediately begin to smile in the midst of overwhelming sorrow. My life has been full of tragedies and if they have not left any visible and indelible effect on me, I owe it to the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita".

Gandhi believed that at the core of every religion was Truth and Love (compassion, nonviolence and the Golden Rule). He also questioned hypocrisy, malpractices and dogma in all religions and was a tireless social reformer. Some of his comments on various religions are:

- "Thus if I could not accept Christianity either as a perfect, or the greatest religion, neither was I then convinced of Hinduism being such. Hindu defects were pressingly visible to me. If untouchability could be a part of Hinduism, it could but be a rotten part or an excrescence. I could not understand the raison d'etre of a multitude of sects and castes. What was the meaning of saying that the Vedas were the inspired Word of God? If they were inspired, why not also the Bible and the Koran? As Christian friends were endeavouring to convert me, so were Muslim friends. Abdullah Sheth had kept on inducing me to study Islam, and of course he had always something to say regarding its beauty". (source: his autobiography)

- "As soon as we lose the moral basis, we cease to be religious. There is no such thing as religion over-riding morality. Man, for instance, cannot be untruthful, cruel or incontinent and claim to have God on his side".

- "The sayings of Muhammad are a treasure of wisdom, not only for Muslims but for all of mankind". The concept of Islamic jihad can also be taken to mean a nonviolent struggle or satyagraha, in the way Gandhi practiced it.

Later in his life when he was asked whether he was a Hindu, he replied:

- "Yes I am. I am also a Christian, a Muslim, a Buddhist and a Jew".

In spite of their deep reverence to each other, Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore got involved in protracted debates more than once. These debates exemplify the philosophical differences between the two most famous Indians at the time. On January 15, 1934, an earthquake hit Bihar and caused extensive damage and loss of life. Gandhi maintained this was because of the sin committed by upper caste Hindus by not letting untouchables in their temples (Gandhi was committed to the cause of improving the fate of untouchables, referring to them as Harijans, people of Krishna). Tagore vehemently opposed Gandhi's stance, maintaining that an earthquake can only be caused by natural forces, not moral reasons, however repugnant the practice of untouchability may be.

Criticism

Throughout his life and after his death, Gandhi has evoked serious criticism. B. R. Ambedkar, the Dalit political leader condemned Gandhi's terming the untouchable community as Harijans, which he found condescending. Ambedkar and his allies also felt Gandhi was undermining Dalit political rights. Muhammad Ali Jinnah and contemporary Pakistanis often condemn Gandhi for undermining Muslim political rights. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar condemned Gandhi for appeasing Muslims politically - Savarkar and his allies blamed Gandhi for thus facilitating the creation of Pakistan and increasing the influence of the Muslim community in politics beyond proportion. Savarkar himself was implicated in the trial following Gandhi's murder, as he was the mentor of the assassin Nathuram Godse and an important Hindu Mahasabha leader. In contemporary times, historians like Ayesha Jalal blame Gandhi and the Congress for being unwilling to share power with Muslims and thus hastening partition. Hindu political extremists like Pravin Togadia and Narendra Modi have been known to criticize Gandhi's leadership and actions.

Gandhi believed that the mind of an oppressor or a bigot could be changed by love and non-violent rejection of wrong actions, while accepting full responsibility for the consequences of the actions. However, Penn and Teller, in an episode of their Showtime program Bullshit! ("Holier than Thou"), attacked Gandhi for, amongst other things, hypocrisy for perceived inconsistent stands on nonviolence, alleged inappropriate behaviour with women and apparent racist statements against Africans. The last allegation is based on an incident in Bombay in 1896. On addressing a public meeting in Bombay on September 26, 1896 (cf. Collected Works Volume II, page 74) following his return from South Africa, Gandhi said:

- Ours is one continued struggle against degradation sought to be inflicted upon us by the European, who desire to degrade us to the level of the raw kaffir, whose occupation is hunting and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with, and then pass his life in indolence and nakedness.

Gandhi has also been criticized by various historians and commentators for his attitudes regarding Hitler and Nazism. Gandhi apparently believed that Hitler's hatred could be transformed by the application of non-violent resistance. Gandhi has come under fire in particular for statements to the effect that the Jews would win God's love if they willingly went to their deaths as martyrs.[26] [27]

Sometimes his prescription of extreme non-violence was severely at odds with the prevailing view of a situation. In 1940, he wrote an open letter to the British people in which he offered them the following plan of action for the second world war:

"I want you to lay down the arms you have as being useless for saving you or humanity. You will invite Herr Hitler and Signor Mussolini to take what they want of the countries you call your possessions. Let them take possession of your beautiful island with your many beautiful buildings... If these gentlemen choose to occupy your homes, you will vacate them. If they do not give you free passage out, you will allow yourself, man, woman and child to be slaughtered... I am telling His Excellency the Viceroy that my services are at the disposal of His Majesty's government, should they consider them of any practical use in enhancing my appeal." (From Stanley Wolpert's "Jinnah of Pakistan.")

Legacy

Gandhi never received the Nobel Peace Prize, though he was nominated for it five times between 1937 and 1948. Decades later however, the Nobel Committee publicly declared its regret for the omission, and admitted to deeply divided nationalistic opinion denying the award to Gandhi. The Prize was not awarded in 1948, the year of Gandhi's death, on the grounds that "there was no suitable living candidate" that year, and when the Dalai Lama was awarded the Prize in 1989, the chairman of the committee said that this was "in part a tribute to the memory of Mahatma Gandhi".[28] After Gandhi's death, Albert Einstein said of Gandhi: "Generations to come will scarcely believe that such a one as this walked the earth in flesh and blood." He also once said," I believe that Gandhi's views were the most enlightened of all the political men in our time. We should strive to do things in his spirit: not to use violence in fighting for our cause, but by non-participation in anything you believe is evil."

Time Magazine named Gandhi as the runner-up to Albert Einstein as "Person of the Century" at the end of 1999, and named The Dalai Lama, Lech Wałęsa, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Cesar Chavez, Aung San Suu Kyi, Benigno Aquino Jr., Desmond Tutu, and Nelson Mandela as Children of Gandhi and his spiritual heirs to the tradition of non-violence. The Government of India awards the annual Mahatma Gandhi Peace Prize to distinguished social workers, world leaders and citizens. Nelson Mandela, the leader of South Africa's struggle to eradicate racial discrimination and segregation, is a prominent non-Indian recipient of this honour. In 1996, the Government of India introduced the Mahatma Gandhi series of currency notes in Rupees 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500 and 1000 denomination.

Mahatma

The word Mahatma, while often mistaken for Gandhi's given name in the West, is taken from the Sanskrit words maha meaning Great and atma meaning Soul. The title "Mahatma" was first accorded to Gandhi on January 21, 1915 by his pioneer supporter Nautamlal Bhagavanji Mehta at the Kamribai School in Jetpur, Gujarat, India (in the erstwhile princely state of Kathiawad). In his autobiography, Gandhi nevertheless explains that he never felt worthy of the honor.[29] According to the manpatra, the name Mahatma was given in response to Gandhi's admirable sacrifice in manifesting justice and truth.[30]

Artistic depictions

The best-known artistic depiction of his life is the film Gandhi (1982), directed by Richard Attenborough, and starring Ben Kingsley (himself of Gujarati parentage from his father's side) in the title role. However, the film has since been criticised by some post-colonial scholars, who argue that it depicts Gandhi as single-handedly bringing India to independence, and ignores other prominent figures (both elite and subaltern) in the anti-colonial struggle. The Making of the Mahatma, directed by Shyam Benegal, and starring Rajat Kapur, is a film about Gandhi's 21 years of life in South Africa. Gandhi's character is played by Anu Kapoor in the film Sardar (1993) about the life of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel.

The 1998 film Hey Ram, made by Kamal Hasan portrays a would-be assassin of Gandhi and the dilemma faced by the would be assassins in the turmoil of post-partition India. Gandhi's character is played by veteran actor Naseeruddin Shah. There are several works explorative of different aspects of Gandhi's life and his controversial actions: the play Mahatma vs. Gandhi explores his troubled relationship with his eldest son Harilal Gandhi, and Me Nathuram Godse Boltoy (Marathi: I am Nathuram Godsé speaking) explores the rationale and circumstances in which Gandhi's murder was plotted and carried out. The opera Satyāgraha , composed by Philip Glass (in 1980), with a libretto by himself and Constance De Jong is based on the life of Gandhi.

Across the world

In the United Kingdom, there are several prominent statues of Gandhi, most notably in Tavistock Square, London (near University College London), where he studied law. January 30 is commemorated in the United Kingdom as National Gandhi Remembrance Day. In the United States, there are statues of Gandhi outside the Ferry Building in San Francisco, Union Square Park in New York City, the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site in Atlanta and near the Indian Embassy in the Dupont Circle neighbourhood of Washington, DC. The city of Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, where Gandhi was ejected in 1893 from a first-class train, now hosts a commemorative statue. The Government of India donated a statue to the city of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, to signify their support for the future Canadian Museum for Human Rights. There are wax statues of Gandhi at the Madame Tussaud's wax museums in New York and London, and other cities around the world, including Moscow, Paris, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Lisbon, Canberra, Santiago de Chile, Mexico City and San Fernando, Trinidad and Tobago.

Notes

- ↑ M. Gandhi, ‘’All Men are Brothers’’, pp54

- ↑ http://www.mkgandhi.org/bio5000/bio5index.htm

- ↑ http://www.mkgandhi.org/bio5000/bio5index.htm

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 82

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 89

- ↑ http://www.mkgandhi.org/bio5000/bio5index.htm

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 105

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 131

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 172

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 230-32

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 246

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 277-81

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 283-86

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 318

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 462

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 464-66

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 472

- ↑ Vinay Lal. ‘Hey Ram’: The Politics of Gandhi’s Last Words. Humanscape 8, no. 1 (January 2001):34-38

- ↑ Trivia Hall of Fame - Mahatma Gandhi. Retrieved from the Wayback Machine, 14 February 2004.

- ↑ Bondurant, p. 28

- ↑ Bondurant, p. 139

- ↑ Vegetarian furore as Gandhi is used to promote eggs. Peter Foster in New Delhi (Filed: 29/08/2005)

- ↑ The Story of My Experiments with truth - An Autobiography, p. 176.

- ↑ The Story of My Experiments with truth - An Autobiography, p. 177.

- ↑ The Story of My Experiments with truth - An Autobiography, p. 183.

- ↑ David Lewis Schaefer. What Did Gandhi Do?. National Review. 28 April 2003. Retrieved 21 March 2006.

- ↑ Richard Grenier. The Gandhi Nobody Knows. Commentary magazine. March 1983. Retrieved 21 March 2006.

- ↑ Øyvind Tønnesson. Mahatma Gandhi, the Missing Laureate. Nobel e-Museum Peace Editor, 1998-2000. Retrieved 21 March 2006

- ↑ M.K. Gandhi: An Autobiography. Retrieved 21 March 2006.

- ↑ Documentation of how and when Mohandas K. Gandhi became known as the "Mahatma". Retrieved 21 March 2006.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments With Truth (available at wikisource) [1] (1929) ISBN 0807059099

- Gandhi: A Photo biography by Peter Rühe ISBN 0714892793

- The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of His Writings on His Life, Work, and Ideas by Louis Fischer ISBN 1400030501

- Gandhi: A Life by Yogesh Chadha ISBN 0471350621

- Gandhi and India: A Century in Focus by Sofri, Gianni (1995) ISBN 1900624125

- The Kingdom of God is Within You [2] by Leo Tolstoy (1894) ISBN 0803294042

- Patel: A Life by Rajmohan Gandhi (1990) ASIN: B0006EYQ0A

- Bondurant, Joan V. (1988). Conquest of Violence: The Gandhian Philosophy of Conflict. Princeton UP. ISBN 0-691-02281-X.

- Exploring Jo'burg with Gandhi, Lucille Davie

- Restored fairview fire tower reopened, Mahatma Gandhi's Troyeville Johannesburg residence. See above link for images

External links

Institutions

- M.K. Gandhi Institute for Nonviolence

- The Official Mahatma Gandhi eArchive & Reference Library

- mkgandhi.org

- The Gandhi Foundation

- Gandhi Information Center

- GandhiServe Foundation Mahatma Gandhi Research and Media Service

- Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya Gandhi Museum & Library Mani Bhavan is the place where Gandhi stayed whenever he was in Mumbai between 1917 and 1934. It was from here that Gandhi initiated his Civil Disobedience, Swadeshi, Khadi and Khilafat movements.

Resources

- Why was Gandhi never awarded the Nobel Peace Prize?

- Films and Footage of Mahatma Gandhi at Video Google

- Mahatma Gandhi News Digest and News Library Daily news about Mahatma Gandhi and India's Independence Movement

- Works by Mahatma Gandhi. Project Gutenberg

- Photo Library of Mahatma Gandhi Over 10,000 images of Gandhi and India’s independence movement – partly digitized

- The Official Mahatma Gandhi Picture Site The Top 100 photographs of Mahatma Gandhi

- Film Footage of Mahatma Gandhi List of 300 film clips – over 10 hours - on Gandhi and India’s independence movement

- Films on Mahatma Gandhi List of over 100 hours of films on Gandhi and India’s independence movement

- Documentary film MAHATMA – Life of Gandhi Online Watch the 5+ hours documentary film on Gandhi’s life and works!

- Mahatma Gandhi’s Voice Online Listen to over 50 hours of Gandhi’s speeches in English and Hindi

- Music Online on Mahatma Gandhi Listen to Gandhi’s favourite songs as well as to music on Gandhi

- Online Audio Library on Mahatma Gandhi Listen to records, audio tapes, radio programmes, events and speeches on Mahatma Gandhi

- Audio Testimonials on Mahatma Gandhi Statements by associates and celebrities on Gandhi

- Albert Einstein on Mahatma Gandhi An audio statement, correspondence with Gandhi and a text document by Einstein

- Writings Online on and by Mahatma Gandhi Read over 200 books and articles on and by Gandhi

- Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi Online Read over 50,000 pages of Gandhi’s letters, speeches, articles and books

- Books on Mahatma Gandhi List of over 8,800 library and current books in German and English on Gandhi and related subjects

- Mahatma Gandhi’s Correspondence List of 35,000 letters - largely - to and from Mahatma Gandhi, incl. a summary of each letter

- Journals on Mahatma Gandhi List of publishers of journals on Gandhi

- Chronologies of Mahatma Gandhi’s Life A brief and a detailed day-to-day chronology of Gandhi’s life

- Stamps, coins, medals, banknotes and cindrella on Mahatma Gandhi from all over the world

- Lick Service to the Mahatma The Story of Gandhi's Life and Legacy told through Philately

- Genealogy of Mahatma Gandhi Genealogical tables on Gandhi and his family with over 1,600 entries

- Oral History on Gandhi on Video Online Watch interviews with freedom fighters of India’s independence movement

- Oral History on Gandhi on Audio Online Listen to interviews with associates of the Mahatma

- Quiz with Mahatma Gandhi Play, enjoy, and learn more about Gandhi

- The Story of My Experiments with Truth Gandhi auto-bio; free download in English or 6 South-Asian languages

- An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth Free e-text

- Better World Links on Gandhi

- Contextualizing Gandhi in Twenty-First Century World

- Mahatma Gandhi - An Average Man - Nadesan Satyendra

- Mahatma Gandhi and the Corea Family of Chilaw Mahatma Gandhi's visit to Ceylon in 1927

- The Gandhi Nobody Knows Critical Review of the movie 'Gandhi', which eventually became a biography of the Indian leader.

- Gandhi on Jews & Middle-East

- Hey Ram: The Politics of Gandhi's Last Words: Critical review of Hey Ram – whether Gandhi really said those words or not.

- Gandhi on Education (National Centre for Teacher Education, New Delhi 1998)

- Gandhi Biography

- Gandhi's Seven Deadly Sins

- Big Picture TV Free video clip of Ela Gandhi talking about her grandfather

- Gandhi at the Internet Movie Database

- Gandhi or Moses? chabad.org

Analysis

- Gandhi and the national liberation of India, 1919-1946 - A critical examination of Gandhi's role in the movement

| Indian Independence Movement | |

|---|---|

| History: | Colonisation - British East India Company - Plassey - Buxar - British India - French India - Portuguese India - More... |

| Philosophies: | Indian nationalism - Swaraj - Gandhism - Satyagraha - Hindu nationalism - Indian Muslim nationalism - Swadeshi - Socialism |

| Events and movements: | Rebellion of 1857 - Partition of Bengal - Revolutionaries - Ghadar Conspiracy - Champaran and Kheda - Jallianwala Bagh Massacre - Non-Cooperation - Flag Satyagraha - Bardoli - 1928 Protests - Nehru Report - Purna Swaraj - Salt Satyagraha - Act of 1935 - Legion Freies Indien - Cripps' mission - Quit India - Indian National Army - Bombay Mutiny |

| Organisations: | Indian National Congress - Ghadar - Home Rule - Khudai Khidmatgar - Swaraj Party - Anushilan Samiti - Azad Hind - More... |

| Indian leaders: | Mangal Pandey - Rani of Jhansi - Bal Gangadhar Tilak - Gopal Krishna Gokhale - Lala Lajpat Rai - Bipin Chandra Pal - Mahatma Gandhi - M. Ali Jinnah - Sardar Patel - Subhash Chandra Bose - Badshah Khan - Jawaharlal Nehru - Maulana Azad - Chandrasekhar Azad - Rajaji - Bhagat Singh - Sarojini Naidu - Purushottam Das Tandon - Tanguturi Prakasam - Alluri Sitaramaraju - More... |

| British Raj: | Robert Clive - James Outram - Dalhousie - Irwin - Linlithgow - Wavell - Stafford Cripps - Mountbatten - More... |

| Independence: | Cabinet Mission - Indian Independence Act - Partition of India - Political integration - Constitution - Republic of India |

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gandhi, Mahatma |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Political leader |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 2 1869 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Porbandar, Gujarat, India |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 30, 1948 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Birla House, New Delhi, India |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.