Difference between revisions of "Ireland" - New World Encyclopedia

Mike Butler (talk | contribs) |

Mike Butler (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 211: | Line 211: | ||

The judiciary consists of the Supreme Court, the High Court, and many lower courts. Judges are appointed by the president after being nominated by the Government, and can be removed from office only for misbehaviour or incapacity, and then only by resolution of both houses of the Oireachtas. The final court of appeal is the Supreme Court, which consists of the Chief Justice and seven other justices. The Supreme Court has the power of [[judicial review]] and may declare to be invalid both laws and acts of the state which are repugnant to the constitution. The legal system is based on English common law, substantially modified by indigenous concepts. Ireland has not accepted compulsory International Court of Justice jurisdiction. | The judiciary consists of the Supreme Court, the High Court, and many lower courts. Judges are appointed by the president after being nominated by the Government, and can be removed from office only for misbehaviour or incapacity, and then only by resolution of both houses of the Oireachtas. The final court of appeal is the Supreme Court, which consists of the Chief Justice and seven other justices. The Supreme Court has the power of [[judicial review]] and may declare to be invalid both laws and acts of the state which are repugnant to the constitution. The legal system is based on English common law, substantially modified by indigenous concepts. Ireland has not accepted compulsory International Court of Justice jurisdiction. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ireland has had a long history of political violence, which remained a key aspect of life in Northern Ireland, where paramilitary groups like the Irish Republican Army were supported by people in the republic. | ||

Ireland joined the [[European Union]] in 1973 but has chosen to remain outside the [[Schengen Treaty]]. Citizens of the UK can freely enter Ireland without a passport thanks to the [[Common Travel Area]], however some form of identification is required at airports and seaports. | Ireland joined the [[European Union]] in 1973 but has chosen to remain outside the [[Schengen Treaty]]. Citizens of the UK can freely enter Ireland without a passport thanks to the [[Common Travel Area]], however some form of identification is required at airports and seaports. | ||

| Line 267: | Line 269: | ||

[[Image:Lough gur.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Lough Gur, an early Irish farming settlement]] | [[Image:Lough gur.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Lough Gur, an early Irish farming settlement]] | ||

As [[archaeology|archaeological]] evidence from sites such as the [[Céide Fields]] in [[County Mayo]] and [[Lough Gur]] in [[County Limerick]] demonstrates, farming in Ireland is an activity that goes back to the very beginnings of human settlement. In historic times, texts such as the [[Táin Bó Cúailinge]] show a society in which [[cattle]] represented a primary source of wealth and status. Little of this had changed by the time of the [[Normans|Norman]] conquest of Ireland in the twelfth century. [[Giraldus Cambrensis]] portrays a Gaelic society in which cattle farming and [[transhumance]] is the norm. Three hundred years later, the society depicted in [[Edmund Spenser]]'s ''A View of the Present State of Ireland'' had changed remarkably little. Even today, when a quarter of the population of the Republic lived in Dublin, the cattle population is of the order of 6.7 million. | As [[archaeology|archaeological]] evidence from sites such as the [[Céide Fields]] in [[County Mayo]] and [[Lough Gur]] in [[County Limerick]] demonstrates, farming in Ireland is an activity that goes back to the very beginnings of human settlement. In historic times, texts such as the [[Táin Bó Cúailinge]] show a society in which [[cattle]] represented a primary source of wealth and status. Little of this had changed by the time of the [[Normans|Norman]] conquest of Ireland in the twelfth century. [[Giraldus Cambrensis]] portrays a Gaelic society in which cattle farming and [[transhumance]] is the norm. Three hundred years later, the society depicted in [[Edmund Spenser]]'s ''A View of the Present State of Ireland'' had changed remarkably little. Even today, when a quarter of the population of the Republic lived in Dublin, the cattle population is of the order of 6.7 million. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Irish peasants were among the first in Europe to be able to buy their landholdings. Most farms are family-owned. Cooperatives handle production and marketing. Pasture and arable land is leased out for 11 months of each year in a traditional system known as ''conacre''. | ||

The economy of Ireland has transformed in recent years from an agricultural focus to one dependent on trade, industry and investment. Economic growth in Ireland averaged an exceptional 10 percent from 1995–2000, and 7 percent from 2001–2004. [[Industry]], which accounts for 46 percent of [[Gross Domestic Product|GDP]], about 80 percent of exports, and 29 percent of the labour force, now takes the place of [[agriculture]] as the country's leading sector. | The economy of Ireland has transformed in recent years from an agricultural focus to one dependent on trade, industry and investment. Economic growth in Ireland averaged an exceptional 10 percent from 1995–2000, and 7 percent from 2001–2004. [[Industry]], which accounts for 46 percent of [[Gross Domestic Product|GDP]], about 80 percent of exports, and 29 percent of the labour force, now takes the place of [[agriculture]] as the country's leading sector. | ||

| Line 356: | Line 360: | ||

===Men and women=== | ===Men and women=== | ||

| + | While equal pay for equal work is guaranteed by law, inequities persist between the genders in pay, access to professional achievement, and respect at work. | ||

===Marriage and the family=== | ===Marriage and the family=== | ||

| − | The [[Constitution of Ireland]] guarantees the rights of the family and the institution of marriage. However, the reality is that social and economic change in recent years has brought about significant changes in family life in the Republic. According to figures published in | + | Marriages are seldom arranged, since most spouses are selected through the individual process of trial and error that characterizes Western European society. Marriages are normally monogamous. Divorce has been legal since 1995. Rural society places great pressure on men and women to marry, especially in poor rural areas where many women leave for the cities or emigrate seeking work and social standing matching their education and expectations. Rural marriage festivals, the most famous of which takes place in Lisdoonvarna, brings people together for marriage matches, but face criticism. |

| + | |||

| + | The nuclear family is the principal domestic unit, although extended families continue to play important roles. Children adopt their father's surnames. First names are often selected to honor a grandparent, and in the Catholic tradition most first names are those of saints. Many families use the Irish form of their names, and children in the national primary school system are taught to know and use the Irish language equivalent of their names. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Constitution of Ireland]] guarantees the rights of the family and the institution of marriage. However, the reality is that social and economic change in recent years has brought about significant changes in family life in the Republic. According to figures published in 2004, 31 percent of all births in the Republic of Ireland occur outside marriage. This compares with 5 percent in [[1980]]. The average age of mothers having their first child was 30 and the fertility rate is an average of 1.98 children. | ||

| − | In the Republic, [[divorce]] became legal on | + | In the Republic, [[divorce]] became legal on February 27, 1997. The 2002 census showed that the number of divorced people in the state stood at 35,100, compared with 9800 in 1996. The number of separated people, including divorces, increased from 87,800 in 1996 to 133,800 in 2002. Cohabiting couples made up 8.4 percent of all family units in 2002 compared with 3.9 pecent in 1996. |

===Townlands, villages, parishes and counties=== | ===Townlands, villages, parishes and counties=== | ||

| Line 368: | Line 377: | ||

===Education=== | ===Education=== | ||

{{seealso|Education in the Republic of Ireland}} | {{seealso|Education in the Republic of Ireland}} | ||

| + | Particular emphasis is placed on education and literacy; 99 percent of the population aged fifteen and over can read and write. The majority of four-year-olds attend nursery school, and all five-year-olds are in primary school. | ||

The education systems are largely under the direction of the government via the [[Minister for Education and Science (Ireland)|Minister for Education and Science]] (currently Mary Hanafin, TD). Recognised primary and secondary schools must adhere to the curriculum established by authorities that have power to set them. | The education systems are largely under the direction of the government via the [[Minister for Education and Science (Ireland)|Minister for Education and Science]] (currently Mary Hanafin, TD). Recognised primary and secondary schools must adhere to the curriculum established by authorities that have power to set them. | ||

| Line 381: | Line 391: | ||

===Class=== | ===Class=== | ||

| + | The Irish regard their culture as egalitarian, reciprocal, and informal. While an English-style rigid class structure is absent, social and economic class distinctions persist through educational and religious institutions, and the professions. At the top of Irish society is a class of wealthy people, who have made fortunes in business, the professions, the arts and through sport. There is a working class, and a middle class. Relative wealth and social class influence choice of school and university, which affects class mobility. Use of language, especially dialect, indicates class and other social standing. Dress codes have relaxed, but designer clothing, good food, travel, and expensive cars and houses, all reflect degrees of wealth. | ||

==Culture== | ==Culture== | ||

| − | |||

===Architecture=== | ===Architecture=== | ||

| Line 619: | Line 629: | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

* [https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ei.html Ireland] World Fact Book 2007, accessed September 6, 2007. | * [https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ei.html Ireland] World Fact Book 2007, accessed September 6, 2007. | ||

| + | * [http://www.everyculture.com/Ge-It/Ireland.html Ireland] Countries and Their Cultures Ge-It, accessed September 7, 2007. | ||

* [http://www.gov.ie/aras {{lang|ga|Áras an Uachtaráin}}] — Official presidential site | * [http://www.gov.ie/aras {{lang|ga|Áras an Uachtaráin}}] — Official presidential site | ||

{{portal|Ireland|Flag of Ireland.svg}} | {{portal|Ireland|Flag of Ireland.svg}} | ||

| Line 628: | Line 639: | ||

* [http://taoiseach.gov.ie/ Taoiseach] — Official prime ministerial site | * [http://taoiseach.gov.ie/ Taoiseach] — Official prime ministerial site | ||

* [http://www.gov.ie/oireachtas/frame.htm Tithe an Oireachtais] — Houses of Parliament, official parliamentary site | * [http://www.gov.ie/oireachtas/frame.htm Tithe an Oireachtais] — Houses of Parliament, official parliamentary site | ||

| − | {{credit|Republic_of_Ireland|153349626|Geography_of_Ireland|153389599|Dublin|153770535|Ireland|153739608|History_of_Ireland|153573666|Culture_of_Ireland|155395470|Politics_of_Ireland|154697385|Economy_of_the_Republic_of_Ireland|152579975|Demographics_of_the_Republic_of_Ireland|153720370}} | + | {{credit|Republic_of_Ireland|153349626|Geography_of_Ireland|153389599|Dublin|153770535|Ireland|153739608|History_of_Ireland|153573666|Culture_of_Ireland|155395470|Politics_of_Ireland|154697385|Economy_of_the_Republic_of_Ireland|152579975|Demographics_of_the_Republic_of_Ireland|153720370|Irish_language|156073764}} |

Revision as of 23:39, 6 September 2007

| Éire Ireland | |||||

| |||||

| Anthem: Amhrán na bhFiann The Soldier's Song | |||||

|

Location of the Ireland (dark green)

– on the European continent (light green dark grey) – in the European Union (light green) | |||||

| Capital | Dublin 53°20.65′N 6°16.05′W | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Largest city | capital | ||||

| Official languages | Irish, English | ||||

| Government | Republic and Parliamentary Democracy | ||||

| - President | Mary McAleese | ||||

| - Taoiseach | Bertie Ahern, TD | ||||

| Independence | from the United Kingdom | ||||

| - Declared | 24 April 1916 | ||||

| - Ratified | 21 January 1919 | ||||

| - Recognised | 6 December 1922 | ||||

| - Current constitution | 29 December 1937 | ||||

| Accession to EU | January 1 1973 | ||||

| Area | |||||

| - Total | 70,273 km² (120th) 27,133 sq mi | ||||

| - Water (%) | 2.00 | ||||

| Population | |||||

| - 2006 estimate | 4,239,848 | ||||

| - Density | 60.3/km² 147.6/sq mi | ||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2006 estimate | ||||

| - Total | $177.2 billion | ||||

| - Per capita | $43,600 | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2006 estimate | ||||

| - Total | $202.9 billion | ||||

| - Per capita | $50,150 | ||||

| HDI (2004) | |||||

| Currency | Euro (€)1 (EUR)

| ||||

| Time zone | WET (UTC+0) | ||||

| - Summer (DST) | IST (WEST) (UTC+1) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .ie2 | ||||

| Calling code | +353 | ||||

Ireland (Irish language: Éire; IPA [ˈeːrʲə]), also described as the "Republic of Ireland", in order to distinguish it from the island of Ireland and from Northern Ireland, is a country in north-western Europe occupying five-sixths of the island of Ireland.

It is bordered by Northern Ireland (part of the United Kingdom) to the north, by the Atlantic Ocean to the west and by the Irish Sea to the east.

The term Republic of Ireland (Irish language: Poblacht na hÉireann) is officially used as "the description of the state."

Name

Bunreacht na hÉireann (Irish), the constitution of Ireland, provides that "the name of the state is Éire, or, in the English language, 'Ireland'." With Irish being named the European Union's 23rd official language in 2007, the state would be referred to in both constitutional official languages, the Irish and English languages, meaning the label 'Éire-Ireland' would be used on various signage and nameplates referring to the state.

The state has had more than one official title. The revolutionary state, declared in 1919 by the large majority of Irish Members of (the United Kingdom) Parliament, elected in 1918, was known as the "Irish Republic"; when the state achieved independence in 1922, it became known as the "Irish Free State" (in the Irish language Saorstát Éireann), a name that was retained until 1937.

Geography

The island of Ireland extends over 32,556 square miles, (84,421 square kilometers) of which 83 percent belong to the republic (70,280 km²;) and the remainder constituting Northern Ireland. The republic is slightly larger than West Virginia.

It is bound to the west by the Atlantic Ocean, to the northeast by the North Channel, to the east is the Irish Sea which reconnects to the ocean via the southwest with St George's Channel and the Celtic Sea.

The ocean is responsible for the rugged western coastline, along which are many islands, peninsulas, and headlands. The main geographical features of Ireland are low central plains surrounded by a ring of coastal mountains. The highest peak is Carrauntoohil (Irish language: Corrán Tuathail), which is at 3406 feet (1038 meters).

The local temperate climate is modified by the North Atlantic Current and is relatively mild. Summer temperatures commonly reach 84ºF (29ºC), and freezes occur only occasionally in winter, with temperatures below 21ºF ( -6ºC) being uncommon. Precipitation is very common, with up to 275 days with rain in some parts of the country.

There are a number of sizable lakes along Ireland's rivers, with Lough Neagh being the largest in Ireland. The island is bisected by the River Shannon, which at 161 miles (259km) with a 70 mile (113km) estuary, is the longest river in Ireland, and which flows south from County Cavan in the north to meet the Atlantic just south of Limerick. The centre of the country is part of the River Shannon watershed, containing large areas of bogland, used for peat extraction and production.

Ireland has fewer animal and plant species than either Britain or mainland Europe because it became an island shortly after the end of the last Ice Age, about 8000 years ago. Many different habitat types are found in Ireland, including farmland, open woodland, temperate forests, conifer plantations, peat bogs, and various coastal habitats.

Forest, of oak, ash, wych elm, birch, and yew, was the natural dominant vegetation, but has been reduced to 5 percent of the total area. Pine was dominant on poorer soils, with rowan and birch. Beech and lime thrive when introduced. Remnants of native forest can be found scattered around the country, in particular in the Killarney National Park.

Only 26 land mammal species are native to Ireland. Some species, such as the red fox, hedgehog, and badger are very common, whereas others, like the Irish hare, red deer and pine marten are less so. Aquatic wild-life - such as species of turtle, shark, whale, dolphin, and others - are common off the coast. About 400 species of birds have been recorded in Ireland. Many of these are migratory, including the swallow. Most of Ireland's bird species come from Iceland, Greenland, Africa among other territories. There are no snakes and only one reptile (the common lizard) is native to the country. Extinct species include the great Irish elk, the wolf, the great auk, and others. Some previously extinct birds - such as the golden eagle - have recently been reintroduced Ireland is noted for the Connemara pony, Irish wolfhound, Kerry blue terrier, while several types of cattle and sheep are recognized as distinct breeds.

Agriculture is the main factor determining land-use patterns in Ireland, leaving limited land to preserve natural habitats in particular for larger wild mammals with greater territorial requirements. With no top predator in Ireland, populations of animals that cannot be controlled by smaller predators (such as the fox) are controlled by annual culling, such as semi-wild populations of deer. Hedgerows, traditionally used for maintaining and demarcating land boundaries, act as a refuge for native wild flora. Their ecosystems stretch across the countryside and act as a network of connections to preserve remnants of the ecosystem that once covered the island.

Pollution from agricultural activities is one of the principal sources of environmental damage. "Runoff" of contaminants into streams, rivers and lakes impact the natural fresh-water ecosystems. Subsidies under the Common Agricultural Policy which supported these agricultural practices and contributed to land-use distortions are undergoing reforms The CAP still subsidises some potentially destructive agricultural practices, however, the recent reforms have gradually decoupled subsidies from production levels and introduced environmental and other requirements.

The capital city is Dublin, population 1,045,769, located near the midpoint of Ireland's east coast, at the mouth of the River Liffey and at the centre of the Dublin Region. Founded as a Viking settlement, the city has been Ireland's primary city for most of the island's history since mediæval times. Today, it is an economic and cultural centre for the island of Ireland, and has one of the fastest growing populations of any European capital city. Other cities include Cork 190,384 in the south, Limerick 90,757 in the mid-west, Galway 72,729 on the west coast, and Waterford 49,213 on the south east coast (see Cities in Ireland).

History

Stone age

A long cold climatic spell prevailed until about 9,000 years ago, and most of Ireland was covered with ice. This era was known as the Ice Age. Sea-levels were lower then, and Ireland, as with its neighbour Britain, instead of being islands, were part of a greater continental Europe. Mesolithic stone age inhabitants arrived some time after 8000 B.C.E. Agriculture arrived with the Neolithic circa 4000 to 4500 B.C.E. where sheep, goats, cattle and cereals were imported from southwest continental Europe. At the Céide Fields in County Mayo, an extensive Neolithic field system - arguably the oldest in the world - has been preserved beneath a blanket of peat. Consisting of small fields separated from one another by dry-stone walls, the Céide Fields were farmed for several centuries between 3500 and 3000 B.C.E. Wheat and barley were the principal crops cultivated.[citation needed]

Celtic colonisation

The Bronze Age, which began around 2500 B.C.E., saw the production of elaborate gold as well as bronze ornaments, weapons and tools. The Iron Age in Ireland was supposedly associated with people known as Celts. They are traditionally thought to have colonised Ireland in a series of waves between the 8th and 1st centuries B.C.E., with the Gaels, the last wave of Celts, conquering the island and dividing it into five or more kingdoms. Many scientists and academic scholars now favour a view that emphasises cultural diffusion from overseas over significant colonisation such as what Clonycavan Man was reported to be. Native accounts are confined to Irish poetry, myth, and archaeology. The exact relationship between Rome and the tribes of Hibernia is unclear; the only references are a few Roman writings.

In medieval times, a monarch (also known as the High King) presided over the (then five) provinces of Ireland. These provinces too had their own kings, who were at least nominally subject to the monarch, who resided at Tara. The written judicial system was the Brehon Law, and it was administered by professional learned jurists who were known as the Brehons.

Saints Palladius and Patrick

According to early medieval chronicles, in 431, Bishop Palladius arrived in Ireland on a mission from Pope Celestine to minister to the Irish "already believing in Christ." The same chronicles record that Saint Patrick, Ireland's patron saint, arrived in 432. There is continued debate over the missions of Palladius and Patrick, but the general consensus is that they both existed and that 7th century annalists may have mis-attributed some of their activities to each other. Palladius most likely went to Leinster, while Patrick is believed to have gone to Ulster, where he probably spent time in captivity as a young man.

The druid tradition collapsed in the face of the spread of the new religion. Irish Christian scholars excelled in the study of Latin and Greek learning and Christian theology in the monasteries that flourished, preserving Latin and Greek learning during the Early Middle Ages. The arts of manuscript illumination, metalworking, and sculpture flourished and produced such treasures as the Book of Kells, ornate jewellery, and the many carved stone crosses that dot the island.

Viking raiders

From the 9th century, waves of Viking raiders plundered monasteries and towns, adding to a pattern of endemic raiding and warfare. Eventually Vikings settled in Ireland, and established many towns, including the modern day cities of Dublin, Cork, Limerick and Waterford. These invasions were finally ended when King Brian BORU defeated the Danes in 1014.

English claim sovereignty

From 1169, Ireland was entered by Cambro-Norman warlords, led by Strongbow, on an invitation from the then King of Leinster. In 1171, King Henry II of England came to Ireland, using the 1155 Bull Laudabiliter issued to him by then Pope Adrian IV, an Englishman, to claim sovereignty over the island, and forced the Cambro-Norman warlords and some of the Gaelic Irish kings to accept him as their overlord. From the 13th century, English law began to be introduced.

Norman-Irish feudal system

By the late thirteenth century the Norman-Irish had established the feudal system throughout most of lowland Ireland. Their settlement was characterised by the establishment of baronies, manors, towns and large land-owning monastic communities, and the county system. The towns of Dublin, Cork, Wexford, Waterford, Limerick, Galway, New Ross, Kilkenny, Carlingford, Drogheda, Sligo, Athenry, Arklow, Buttevant, Carlow, Carrick-on-Suir, Cashel, Clonmel, Dundalk, Enniscorthy, Kildare, Kinsale, Mullingar, Naas, Navan, Nenagh, Thurles, Wicklow, Trim and Youghal were all under Norman-Irish control.

xxx The Normans also introduced the manorial system of land tenure and social organisation. This led to the imposition of the village and parish over the native system of townlands. In general, a parish was a civil and religious unit with a manor, a village and a church at its centre. Each parish incorporated one or more existing townlands into its boundaries. xxx

Gaelic resurgence

In the 14th century the English settlement went into a period of decline and large areas, for example Sligo, were re-occupied by Gaelic septs. The medieval English presence in Ireland was deeply shaken by Black Death, which arrived in Ireland in 1348.

Re-conquest and rebellion

From the late 15th century English rule was once again expanded, first through the efforts of the Earls of Kildare and Ormond then through the activities of the Tudor State under Henry VIII and Mary and Elizabeth. This resulted in the complete conquest of Ireland by 1603 and the final collapse of the Gaelic social and political superstructure at the end of the 17th century, as a result of English and Scottish Protestant colonisation in the Plantations of Ireland, and the disastrous Wars of the Three Kingdoms and the Williamite War in Ireland. Approximately 600,000 people, nearly half the Irish population, died during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland.

xxx With the full extension of English feudalism over the island, the Irish county structure came into existence. xxx

Civil wars and penal laws

After the Irish Rebellion of 1641, Irish Catholics were barred from voting or attending the Irish Parliament. The new English Protestant ruling class was known as the Protestant Ascendancy. Towards the end of the 18th century the entirely Protestant Irish Parliament attained a greater degree of independence from the British Parliament than it had previously held. Under the Penal Laws no Irish Catholic could sit in the Parliament of Ireland, even though some 90% of Ireland's population was native Irish Catholic when the first of these bans was introduced in 1691. This ban was followed by others in 1703 and 1709 as part of a comprehensive system disadvantaging the Catholic community, and to a lesser extent Protestant dissenters.

Colonial Ireland 1691-1801

In 1798, many members of this dissenter tradition made common cause with Catholics in a rebellion inspired and led by the Society of United Irishmen. It was staged with the aim of creating a fully independent Ireland as a state with a republican constitution. Despite assistance from France the Irish Rebellion of 1798 was put down by British forces.

Union with Great Britain 1801-1922

In 1800, the British and subsequently the unrepresentative Irish Parliament passed the Act of Union which, in 1801, merged the Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of Great Britain to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The passage of the Act in the Irish Parliament was achieved with substantial majorities, in part (according to contemporary documents) through bribery, namely the awarding of peerages and honours to critics to get their votes.[1] Thus, Ireland became part of an extended United Kingdom, ruled directly by the UK Parliament in London. The 19th century saw the Great Famine of the 1840s, during which one million Irish people died and over a million emigrated. By the 1840s as a result of the famine fully half of all immigrants to the United States originated from Ireland. A total of 35 million Americans (12% of total population) reported Irish ancestry in the 2005 American Community Survey.[2] Mass emigration became entrenched as a result of the famine and the population continued to decline until late in the 20th century. The pre-famine peak was over 8 million recorded in the 1841 census. The population has never returned to this level [3].

Home rule and the war of independence

The 19th and early 20th century saw the rise of Irish Nationalism especially among the Catholic population. Daniel O'Connell led a successful unarmed campaign for Catholic Emancipation. A subsequent campaign for Repeal of the Act of Union failed. Later in the century Charles Stewart Parnell and others campaigned for self government within the Union or "Home Rule". An armed rebellion took place with the Easter Rising of 1916, and the subsequent Irish War of Independence. In 1921, a treaty was concluded between the British Government and the leaders of the Irish Republic. The Treaty recognised the two-state solution created in the Government of Ireland Act 1920. Northern Ireland was presumed to form a home rule state within the new Irish Free State unless it opted out. Northern Ireland had a majority Protestant population and opted out as expected, its in-built majority choosing to remain part of the United Kingdom, incorporating within its border a significant Catholic/Nationalist minority. A Boundary Commission was set up to decide on the boundaries between the two Irish states, though it was subsequently abandoned after it recommended only minor adjustments to the border. Disagreements over some provisions of the treaty led to a split in the Nationalist movement and subsequently to the Civil War. The civil war ended in 1923 with the defeat of the Anti-treaty forces.

Republic of Ireland

A failed 1916 Easter Monday Rebellion touched off several years of guerrilla warfare that in 1921 resulted in independence from the UK for 26 southern counties.

The state known today as the Republic of Ireland came into being when 26 of the counties of Ireland seceded from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (UK) in 1922. The remaining six counties remained within the UK as Northern Ireland. This action, known as the Partition of Ireland, came about because of complex constitutional developments in the early twentieth century.

It was preceded by the Easter Rising of 1916, when Irish volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army took over sites in Dublin and Galway under terms expressed in the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. The seven signatories of this proclamation, Patrick Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh, Thomas Clarke, Sean MacDiarmada, Joseph Plunkett, Eamonn Ceannt and James Connolly, were executed, along with nine others, and thousands were interned precipitating the Irish War of Independence.

From 1 January 1801 until 6 December 1922, Ireland had been part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. During the Great Famine from 1845 to 1849 the island's population of over 8 million fell by 30 percent. One million Irish died of starvation and another 1.5 million emigrated,[4] which set the pattern of emigration for the century to come and would result in a constant decline up to the 1960s. From 1874, but particularly from 1880 under Charles Stewart Parnell, the Irish Parliamentary Party moved to prominence with its attempts to achieve Home Rule, which would have given all of Ireland some autonomy without requiring it to leave the United Kingdom. It seemed possible in 1911 when the House of Lords lost their veto, and John Redmond secured the Third Home Rule Act 1914.

The unionist movement, however, had been growing since 1886 among Irish Protestants, fearing that they would face discrimination and lose economic and social privileges if Irish Catholics were to achieve real political power. Though Irish unionism existed throughout the whole of Ireland, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century unionism was particularly strong in parts of Ulster, where industrialisation was more common in contrast to the more agrarian rest of the island. (Any tariff barriers would, it was feared, most heavily hit that region.) In addition, the Protestant population was more strongly located in Ulster, with unionist majorities existing in about four counties. Under the leadership of the Dublin-born Sir Edward Carson and the northerner Sir James Craig they became more militant. In 1914, to avoid rebellion in Ulster, the British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, with agreement of the leadership of the Irish Party leadership, inserted a clause into the bill providing for home rule for 26 of the 32 counties, with an as of yet undecided new set of measures to be introduced for the area temporarily excluded. Though it received the Royal Assent, the Third Home Rule Act 1914's implementation was suspended until after the Great War. (The war at that stage was expected to be ended by 1915, not the four years it did ultimately last.) For the prior reasons of ensuring the implementation of the Act at the end of the war Redmond and his Irish National Volunteers supported the Allied cause, and tens of thousands joined battalions of the 10th and 16th (Irish) Divisions of the New British Army.

Template:History of Ireland In January 1919, after the December 1918 general elections, 73 of Ireland's 106 MPs elected were Sinn Féin members who refused to take their seats in the British House of Commons. Instead, they set up an extra-legal Irish parliament called Dáil Éireann. This Dáil in January 1919 issued a Unilateral Declaration of Independence and proclaimed an Irish Republic. The Declaration was mainly a restatement of the 1916 Proclamation with the additional provision that Ireland was no longer a part of the United Kingdom. Despite this, the new Irish Republic remained unrecognised internationally except by Lenin's Russian Republic. Nevertheless the Republic's Aireacht (ministry) sent a delegation under Ceann Comhairle Seán T. O'Kelly to the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, but it was not admitted.

After the bitterly fought War of Independence, representatives of the British government and the Irish treaty delegates, led by Arthur Griffith, Robert Barton and Michael Collins negotiated the Anglo-Irish Treaty in London from October 11th -6th December 1921. The Irish delegates set up headquarters at Hans Place in Knightsbridge and it was here in private discussions that the decision was taken at 11.15am on 5th December to recommend the Treaty to Dáil Éireann. Under the Treaty the British agreed to the establishment of an independent Irish State whereby the Irish Free State (in the Irish language Saorstát Éireann) with dominion status was created. The Dáil Éireann narrowly ratified the treaty.

The Treaty was not entirely satisfactory to either side. It gave more concessions to the Irish than the British had intended to give but did not go far enough to satisfy republican aspirations. The new Irish Free State was in theory to cover the entire island, subject to the proviso that six counties in the north-east, termed "Northern Ireland" (which had been created as a separate entity under the Government of Ireland Act 1920) could opt out and choose to remain part of the United Kingdom, which they duly did. The remaining twenty-six counties became the Irish Free State, a constitutional monarchy over which the British monarch reigned (from 1927 with the title King of Ireland). It had a Governor-General, a bicameral parliament, a cabinet called the "Executive Council" and a prime minister called the President of the Executive Council.

The Irish Civil War was the direct consequence of the creation of the Irish Free State. Anti-Treaty forces, led by Éamon de Valera, objected to the fact that acceptance of the Treaty abolished the Irish Republic of 1919 to which they had sworn loyalty, arguing in the face of public support for the settlement that the "people have no right to do wrong". They objected most to the fact that the state would remain part of the British Commonwealth and that Teachtaí Dála would have to swear an oath of fidelity to King George V and his successors. Pro-Treaty forces, led by Michael Collins, argued that the Treaty gave "not the ultimate freedom that all nations aspire to and develop, but the freedom to achieve it".

At the start of the war, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) split into two opposing camps: a pro-treaty IRA and an anti-treaty IRA. The pro-Treaty IRA became part of the new National Army. However, through the lack of an effective command structure in the anti-Treaty IRA, and their defensive tactics throughout the war, Collins and his pro-treaty forces were able to build up an army capable of overwhelming the anti-Treatyists. British supplies of artillery, aircraft, machine-guns and ammunition boosted pro-treaty forces, and the threat of a return of Crown forces to the Free State removed any doubts about the necessity of enforcing the treaty. The lack of public support for the anti-treaty Irregulars, and the determination of the government to overcome them, contributed significantly to their defeat.

The National Army suffered 800 fatalities and perhaps as many as 4,000 people were killed altogether. As their forces retreated, the Irregulars showed a major talent for destruction and the economy of the Free State suffered a hard blow in the earliest days of its existence.

On 29 December 1937, a new constitution, the Constitution of Ireland, came into force. It replaced the Irish Free State by a new state called simply "Ireland". Though this state's constitutional structures provided for a President of Ireland instead of a king, it was not technically a republic; the principal key role possessed by a head of state, that of symbolically representing the state internationally remained vested, in statute law, in the King as an organ.

The Irish state remained neutral during World War II.[5]

On 21 December 1948, the Republic of Ireland Act declared a republic, with the functions previously given to the Governor-General acting on the behalf of the King given instead to the President of Ireland.

The Irish state had remained a member of the then-British Commonwealth after independence until the declaration of a republic on 18 April 1949. Under Commonwealth rules declaration of a republic automatically terminated membership of the association; since a reapplication for membership was not made, Ireland consequently ceased to be a member.

The Republic of Ireland joined the United Nations in 1955 and the European Community (now the European Union) in 1973. Irish governments have sought the peaceful reunification of Ireland and have usually cooperated with the British government in the violent conflict involving many paramilitaries and the British Army in Northern Ireland known as "The Troubles". A peace settlement for Northern Ireland, the Belfast Agreement, was approved in 1998 in referendums north and south of the border, and is currently being implemented.

Government and politics

Structure

The politics of the Republic of Ireland take place in a framework of a parliamentary representative democratic republic. The Uachtarán (president) is the head of state. The Taoiseach (prime minister) is the head of government], and of a pluriform multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the Oireachtas the bicameral national parliament, which consists of Dáil Éireann and Seanad Éireann. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature. While there are a number of important political parties in the state, the political landscape is dominated by Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, historically opposed and competing entities. The state is a member of the European Union.

The state operates under the Constitution of Ireland, officially known as Bunreacht na hÉireann, adopted in 1937, which falls within the liberal democratic tradition.

The president, who serves as head of state, and is elected for a seven-year term and can be re-elected only once, is largely a figurehead but can still carry out certain constitutional powers and functions, aided by the Council of State, an advisory body.

Executive authority is exercised by a cabinet known simply as the Government. The cabinet may consist of between seven and 15 members, namely the Taoiseach (prime minister), the Tánaiste (deputy prime minister) and up to 13 other ministers. The Taoiseach, normally the leader of the political party which wins the most seats in the national elections, is appointed by the President, after being nominated by Dáil Éireann (the lower house of parliament). The remaining ministers are nominated by the Taoiseach and appointed by the president following their approved by the Dáil.

The bicameral parliament is the Oireachtas, which consists of the president and two houses: Dáil Éireann and Seanad Éireann (also known as the Senate). The Dáil is by far the dominant House of the legislature. The president may not veto bills passed by the Oireachtas, but may refer them to the Irish Supreme Court for a ruling on whether the comply with the constitution.

The 166 members of the Dáil (Teachta Dála) are directly elected at least once in every five years under the single transferable vote form of proportional representation from mulit-seat constituencies. The Taoiseach, Tánaiste and the Minister for Finance must be members of the Dáil.

The Seanad Éireann (senate) is a largely advisory body, and consists of 60 senators. An election for the Seanad must take place no later than 90 days after a general election for the members of the Dáil. Eleven senators are nominated by the Taoiseach while a further six are elected by certain national universities. The remaining 43 are elected from special vocational panels of candidates, the electorate for which consists of the 60 members of the outgoing senate, the 166 members of the recently elected Dáil and the 883 elected members of Ireland's 29 County Borough Councils.

Suffrage is universal to those aged 18 years and over.

It has become normal in the Republic for coalitions to form a government, and there has not been a single-party government since 1989. The 2007 government consisted of a coalition of three parties; Fianna Fáil under Taoiseach Bertie Ahern, the Green Party under new leader John Gormley and the Progressive Democrats under Minister for Health and Children Mary Harney. The main opposition in the 2007 Dáil consisted of Fine Gael under Enda Kenny, The Labour Party under Pat Rabbitte and Sinn Féin. A number of independent deputies also sit in Dáil Éireann. The last scheduled general election to the Dáil took place on May 24, 2007.

The judiciary consists of the Supreme Court, the High Court, and many lower courts. Judges are appointed by the president after being nominated by the Government, and can be removed from office only for misbehaviour or incapacity, and then only by resolution of both houses of the Oireachtas. The final court of appeal is the Supreme Court, which consists of the Chief Justice and seven other justices. The Supreme Court has the power of judicial review and may declare to be invalid both laws and acts of the state which are repugnant to the constitution. The legal system is based on English common law, substantially modified by indigenous concepts. Ireland has not accepted compulsory International Court of Justice jurisdiction.

Ireland has had a long history of political violence, which remained a key aspect of life in Northern Ireland, where paramilitary groups like the Irish Republican Army were supported by people in the republic.

Ireland joined the European Union in 1973 but has chosen to remain outside the Schengen Treaty. Citizens of the UK can freely enter Ireland without a passport thanks to the Common Travel Area, however some form of identification is required at airports and seaports.

Counties

The Republic of Ireland traditionally had 26 counties, and these are still used in cultural and sporting contexts. Dáil constituencies are required by statute to follow county boundaries, as far as possible. Hence counties with greater populations have multiple constituencies (e.g. Limerick East/West) and some constituencies consist of more than one county (e.g. Sligo-North Leitrim), but by and large, the actual county boundaries are not crossed.

As local government units, however, some have been restructured, with the now-abolished County Dublin distributed among three new county councils in the 1990s and County Tipperary having been administratively two separate counties since the 1890s, giving a present-day total of 29 administrative counties and five cities. The five cities — Dublin, Cork, Limerick, Galway, and Waterford (Kilkenny is a city but does not possess a city council) — are administered separately from the remainder of their respective counties. Five boroughs — Clonmel, Drogheda, Kilkenny, Sligo and Wexford — have a level of autonomy within the county:

| Map of the Republic of Ireland with numbered counties. | Republic of Ireland

|

|

These counties are grouped together into regions for statistical purposes.

Military

Ireland's armed forces are organised under the Irish Defence Forces (Óglaigh na hÉireann). The Irish Army is relatively small compared to other neighbouring armies in the region, but is well equipped, with 8500 full-time military personnel (13,000 in the reserve army). This is principally due to Ireland's policy of neutrality, and its "triple-lock" rules governing participation in conflicts. Deployments of Irish soldiers cover UN peace-keeping duties, protection of the Republic's territorial waters (in the case of the Irish Naval Service) and Aid to Civil Power operations in the state.

There is also an Irish Air Corps and Reserve Defence Forces (Irish Army Reserve and Naval Service Reserve) under the Defence Forces. The Irish Army Rangers is a special forces branch which operates under the aegis of the army.

Over 40,000 Irish servicemen have served in UN peacekeeping missions around the world.

The Republic supplies support to the USA military, facilitating the delivery of the bulk of the military personnel involved in the 2003 invasion of Iraq through Shannon Airport; previously the airport had been used for the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. This is part of a longer history of use of Shannon for controversial military transport, which is largely unbiased towards any particular military alliance. The airport was used previously by the US in the First Gulf War and by the Soviet Union during the Cuban Missile Crisis. During the Second World War, though officially neutral, the Republic supplied similar, though more extensive, support for the Allied Forces.

Economy

As archaeological evidence from sites such as the Céide Fields in County Mayo and Lough Gur in County Limerick demonstrates, farming in Ireland is an activity that goes back to the very beginnings of human settlement. In historic times, texts such as the Táin Bó Cúailinge show a society in which cattle represented a primary source of wealth and status. Little of this had changed by the time of the Norman conquest of Ireland in the twelfth century. Giraldus Cambrensis portrays a Gaelic society in which cattle farming and transhumance is the norm. Three hundred years later, the society depicted in Edmund Spenser's A View of the Present State of Ireland had changed remarkably little. Even today, when a quarter of the population of the Republic lived in Dublin, the cattle population is of the order of 6.7 million.

Irish peasants were among the first in Europe to be able to buy their landholdings. Most farms are family-owned. Cooperatives handle production and marketing. Pasture and arable land is leased out for 11 months of each year in a traditional system known as conacre.

The economy of Ireland has transformed in recent years from an agricultural focus to one dependent on trade, industry and investment. Economic growth in Ireland averaged an exceptional 10 percent from 1995–2000, and 7 percent from 2001–2004. Industry, which accounts for 46 percent of GDP, about 80 percent of exports, and 29 percent of the labour force, now takes the place of agriculture as the country's leading sector.

Exports play a fundamental role in the state's robust growth, but the economy also benefits from the accompanying rise in consumer spending, construction, and business investment. On paper, the country is the largest exporter of software-related goods and services in the world. In fact, a lot of foreign software, and sometimes music, is filtered through the country to avail of the state's non-taxing of royalties from copyrighted goods.

Exports totalled $119.8-billion in 2006. Export commodities included machinery and equipment, computers, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, live animals, and animal products. Export partners included US 18.8 percent, UK 17.4 percent, Belgium 15.9 percent, Germany 7.5 percent, France 5.6 percent, Italy 4.1 percent.

Imports totalled $87.36-billion in 2006. Import commodities included data processing equipment, other machinery and equipment, chemicals, petroleum and petroleum products, textiles, and clothing. Import partners included UK 37.3 percent, US 11.6 percent, Germany 9.5 percent, and Netherlands 4.6 percent.

A key part of economic policy, since 1987, has been Social Partnership which is a neo-corporatist set of voluntary "pay pacts" between the Government, employers and trades unions. These usually set agreed pay rises for three-year periods.

The state joined in launching the Euro currency system in January 1999 (leaving behind the Irish pound) along with 11 other EU nations. The 1995-to-2000 period of high economic growth led many to call the country the Celtic Tiger. The economy felt the impact of the global economic slowdown in 2001, particularly in the high-tech export sector — the growth rate in that area was cut by nearly half. GDP growth continued to be relatively robust, with a rate of about 6 percent in 2001 and 2002. Growth for 2004 was over 4 percent, and for 2005 was 4.7 percent.

With high growth came high levels of inflation, particularly in the capital city. Prices in Dublin, where nearly 30 percent of Ireland's population lives, are considerably higher than elsewhere in the country, especially in the Irish property market.

Per capita income

Measuring Ireland's level of income per capita is a complicated issue. Ireland possesses the second highest GDP (PPP) per capita in the world (US$43,600 as of 2006), behind Luxembourg, and the fourth highest Human Development Index, which is calculated partially on the basis of GDP per capita. However, many economists feel that GDP per capita is an inappropriate measure of national income for Ireland, as it neglects the fact that much income generated in Ireland belongs to multinational companies and eventually goes offshore. Another measure, Gross National Income per head, takes account of this and therefore many economists feel it is a superior measure of income in the country. In 2005, the World Bank measured Ireland's GNI per head at $41,140 - the seventh highest in the world, sixth highest in Western Europe, and the third highest of any EU member state. Also, a study by The Economist found Ireland to have the best quality of life in the world. (![]() PDF) This study employed GDP per capita as a measure of income rather than GNI per capita.

PDF) This study employed GDP per capita as a measure of income rather than GNI per capita.

The positive reports and economic statistics mask several underlying imbalances. The construction sector, which is inherently cyclical in nature, now accounts for a significant component of Ireland's GDP. A recent downturn in residential property market sentiment has highlighted the over-exposure of the Irish economy to construction, which now presents a threat to economic growth.

Taxation

Governments have favoured a low taxation policy to encourage foreign direct investment in Ireland. Consequently, the government opposes moves by the European Commission to restrict tax competition. The corporate tax rate is only 12.5 percent, versus between 15 percent and 60 percent in the rest of Europe. The income tax system is designed to redistribute wealth from the richer to the poorer segments of society. There are two tax bands, based on income levels. These range from a maximum top rate of 41 percent, to a maximum bottom rate of 20 percent. In reality, however, a generous tax credits system ensures that the lower rates of taxation are normally 4 percent to 12 percent. The top rate of tax never exceeds 35 percent in practice.

The government receives much of its revenues from taxes on goods — these include a 21% VAT rate on most consumer goods, high levels of excise duty on tobacco, petrol, and alcohol and several smaller taxes on items such as plastic bags, cheques, ATM cards, credit cards and debit cards. The taxes in the personal financial sector

Wealth disparities

Large disparities in wealth exist between those employed and those dependent on welfare payments. The percentage of the population at risk of relative poverty was 21 percent in 2004 - one of the highest rates in the European Union. Poverty figures show that 6.8 percent of Ireland's population suffer "consistent poverty". The unemployment rate was 4.3 percent in 2006.

Several successive years of unbalanced economic growth have also led to huge inequality between the strata of Irish society. Large and sustained increases in property values from 2002-06 have had a substantial impact on the distribution of wealth. The high level of inequality in Ireland today is evident from an annual publication[6] issued by the Bank of Ireland detailing the sources of wealth in Ireland.

The Irish government runs a Welfare state system. The government provides free education at all levels for all EU citizens. Free healthcare is not universal, being restricted to the unemployed and very low earners at the General practitioner level. People who are unemployed receive unemployment benefits and retired people are entitled to a state pension - both benefits are quite high by international comparisons.

Transport

The Republic of Ireland has three main international airports (Dublin, Shannon, and Cork) that serve a wide variety of European and intercontinental routes with scheduled and chartered flights. The national airline is Aer Lingus, although low cost airline Ryanair is the largest airline. The route between London and Dublin is the busiest international air route in Europe, with 4.5 million people flying between the two cities in 2006.

Railways services are provided by Iarnród Éireann. Dublin is the centre of the network, with two main stations (Heuston and Connolly) linking to the main towns and cities. The Enterprise service, run jointly with Northern Ireland Railways connects Dublin with Belfast. The motorways and major trunk roads are managed by the National Roads Authority. The rest of the road network is managed by the local authorities in each of their areas. Regular ferry services operate between the Republic of Ireland and Great Britain, the Isle of Man and France.

On independence, the cities of Dublin and Cork both had extensive light rail networks, as did many parts of the country-side, such as the West-Clare and West-Kerry railways. Cork's light rail network was removed from service in 1931 after the transfer of authority for them from the Cork city electricity company to the Irish Omnibus Company. Trams in Dublin were phased out between 1940 and 1944. Following closure, tram lines were dug up, and equipment and facilities sold-off. Tram service in Ireland was not operated again in Ireland until 2004, when the first two lines of a new light-rail system known as Luas, the Irish word for speed, were opened in Dublin. It features on-street running in the city centre, but is considered a light-rail system because it runs along a dedicated right-of-way for much of its route. There are seven more Luas projects planned, all of which are to be complete by 2015. Two light-metro lines are also to be built by 2014 as well; which is a similar idea to light rail, though will be fully segregated from traffic.

Demographics

Population changes

Birth rates in Ireland were over double the death rates in 2007, which is unique among Western European countries, and the nation seems to be in the midst of a baby boom. According to the 2006 Census, the total population of Ireland on Census Day, April 23, 2006, was 4,234,925, an increase of 317,722, or 8.1 percent since 2002. The 1861 Census recorded a population of 4.4 million, while the lowest population was recorded in the 1961 Census – 2.6 million. Allowing for the incidence of births (245,000) and deaths (114,000), the derived net immigration of people to Ireland between 2002 and 2006 was 186,000. The total number of non-nationals (foreign citizens) living in Ireland was 419,733, or around 10 percent. The single largest group of immigrants comes from the United Kingdom (112,548) followed by Poland (63,267), Lithuania (24,628), Nigeria (16,300), Latvia (13,319), the United States (12,475), China (11,161), and Germany (10,289).

Ethnicity

Genetic research suggests that the first settlers of Ireland, and parts of North-Western Europe, came through migrations from Iberia following the end of the most recent ice age After the Mesolithic, the Neolithic and Bronze Age migrants introduced Celtic culture and languages to Ireland. These later migrants from the Neolithic to Bronze Age still represent a minority of the genetic heritage of Irish people. Culture spread throughout the island, and the Gaelic tradition became the dominant form in Ireland. Today, Irish people are mainly of Gaelic ancestry, and although some of the population is also of Norse, Anglo-Norman, English, Scottish, French and Welsh ancestry, these groups have been assimilated and do not form distinct minority groups. Gaelic culture and language forms an important part of national identity. The Irish Travellers are an ethnic minority group, politically (but not ethnically) linked with mainland European Roma and Gypsy groups.

A total 94.8 percent of the population was recorded as having a "white" ethnic or cultural background, while 1.1 percent of the population had a "black or black Irish" background, 1.3 percent had an "Asian or Asian Irish' background and 1.7 percent of the population's ethnic or cultural background was "not stated."

Religion

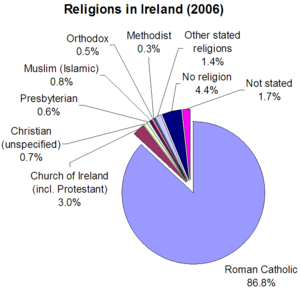

The Republic of Ireland is 86.8 percent Roman Catholic, and has one of the highest rates of regular and weekly church attendance in the Western World. However, there has been a major decline in this attendance among Irish Catholics in the course of the past 30 years. Between 1996 and 2001, regular Mass attendance, declined further from 60 percent to 48 percent (it had been above 90 percent before 1973), and all but two of its sacerdotal seminaries have closed (St Patrick's College, Maynooth and St Malachy's College, Belfast). A number of theological colleges continue to educate both ordained and lay people.

The second largest Christian denomination, the Church of Ireland (Anglican), having been declining in number for most of the twentieth century, but has more recently shown an increase in membership, according to the 2002 census, as have other small Christian denominations, and Hinduism. The largest other Protestant denominations are the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, followed by the Methodist Church in Ireland. The very small Jewish community in the state also recorded a marginal increase (see History of the Jews in Ireland) in the same period.

The patron saints of Ireland are Saint Patrick and Saint Bridget.

According to the 2006 census, the number of people who described themselves as having "no religion" was 186,318 (4.4 percent). An additional 1515 people described themselves as agnostic and 929 as atheist instead of ticking the "no religion" box. This brings the total nonreligious within the state to 4.5 percent of the population. A further 70,322 (1.7 percent) did not state a religion.

Catholic doctrine and the constitution

The 1937 Constitution of Ireland gave the Roman Catholic Church a "special position" as the church of the majority, but also recognised other Christian denominations and Judaism. As with other predominantly Roman Catholic European states (Italy), the Irish state underwent a period of legal secularisation in the late twentieth century. In 1972, the articles mentioning specific religious groups, including the Catholic Church were deleted from the Irish constitution by the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland.

Article 44, which remains in the constitution, says that: The State acknowledges that the homage of public worship is due to Almighty God. It shall hold His Name in reverence, and shall respect and honour religion. The article also establishes freedom of religion, prohibits endowment of any particular religion, prohibits the state from religious discrimination, and requires the state to treat religious and non-religious schools in a non-prejudicial manner.

Catholic doctrine prohibits abortion in all circumstances, putting it in conflict with the pro-choice movement. In 1983, the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland recognised "the right to life of the unborn", subject to qualifications concerning the "equal right to life" of the mother. The case of Attorney General v. X prompted passage of the Thirteenth and Amendments, guaranteeing the right to travel abroad to have an abortion performed, and the right of citizens to learn about "services" that are illegal in Ireland but legal outside the country.

Catholic and Protestant attitudes in 1937 also disapproved of divorce, which was prohibited by the original constitution. It was not until 1995 that the Fifteenth Amendment repealed this ban.

The Catholic Church was hit in the 1990s by a series of sexual abuse scandals and cover-up charges against its hierarchy. In 2005, a major inquiry was made into child sexual abuse allegations. The Ferns report, published on October 25, 2005, revealed that more than 100 cases of child sexual abuse, between 1962 and 2002, by 21 priests, had taken place in the Diocese of Ferns alone. The report criticised the Gardaí and the health authorities, who failed to protect the children to the best of their abilities; and in the case of the Garda before 1988, no file was ever recorded on sexual abuse complaints.

Despite most schools in Ireland being run by religious organisations, a general trend of secularism is occurring within the Irish population, particularly in the younger generations. Many efforts have been made by secular groups, to eliminate the rigorous study of prayer in the first and sixth classes, to prepare for the sacraments of holy communion and confirmation. However religious studies as a subject was introduced into the state administered "Junior certificate" in 2001.

In the past, Ireland has historically favoured conservative legislation regarding sexuality. For example, contraception was illegal in Ireland until 1979. Another example is the legislation which outlawed homosexual acts was not repealed until 1993 although it was generally only enforced when dealing with underage sex.Though Senator David Norris took his successful case to the European Court of Human Rights in 1988, the Irish Government did not legislate to rectify the issue until 1993.

Languages

The official languages are Irish and English. Irish (Gaeilge) is a Celtic language of the Goidelic language family branch. Although once spoken across the whole of the island, it is a minority vernacular in Ireland, spoken in specific communities and most particularly in the officially-recognised Gaeltacht, which exists in six separate communities around the Republic of Ireland. Teaching of the Irish and English languages is compulsory in the primary and secondary level schools that receive money and recognition from the state. Some students may be exempt from the requirement to receive instruction in either language.

English is by far the predominant language spoken throughout the country. People living in predominantly Irish-speaking Gaeltacht regions, are limited to the low tens of thousands in isolated pockets largely on the western seaboard. Road signs are usually bilingual, except in Gaeltacht regions, where they are in Irish only. The legal status of place names has recently been the subject of controversy, with an order made in 2005 under the Official Languages Act changing the official name of certain locations from English back to Irish (e.g. Dingle had its name changed to An Daingean, but was then renamed to "Dingle Daingean Ui Chuis"), sometimes despite local opposition, and, in Dingle's case, a plebiscite requesting a name change to a bilingual version. Most public notices are only in English, as are most of the print media. Most Government publications and forms are available in both English and Irish, and citizens have the right to deal with the state in Irish if they so wish. National media in Irish exist on TV (TG4), radio (Raidió na Gaeltachta), and in print (Lá Nua and Foinse).

According to the 2006 census, 1,656,790 people (or 39 percent) in the Republic regard themselves as competent in Irish; though no figures are available for English-speakers, it is thought to be almost 100 percent.

The Polish language is one of the most widely-spoken languages in Ireland after English and Irish: there are over 63,000 Poles resident in Ireland according to the 2006 census. Other languages spoken in Ireland include Shelta, spoken by the Irish Traveller population and a dialect of Scots is spoken by the descendents of Scottish settlers in Ulster.

Men and women

While equal pay for equal work is guaranteed by law, inequities persist between the genders in pay, access to professional achievement, and respect at work.

Marriage and the family

Marriages are seldom arranged, since most spouses are selected through the individual process of trial and error that characterizes Western European society. Marriages are normally monogamous. Divorce has been legal since 1995. Rural society places great pressure on men and women to marry, especially in poor rural areas where many women leave for the cities or emigrate seeking work and social standing matching their education and expectations. Rural marriage festivals, the most famous of which takes place in Lisdoonvarna, brings people together for marriage matches, but face criticism.

The nuclear family is the principal domestic unit, although extended families continue to play important roles. Children adopt their father's surnames. First names are often selected to honor a grandparent, and in the Catholic tradition most first names are those of saints. Many families use the Irish form of their names, and children in the national primary school system are taught to know and use the Irish language equivalent of their names.

The Constitution of Ireland guarantees the rights of the family and the institution of marriage. However, the reality is that social and economic change in recent years has brought about significant changes in family life in the Republic. According to figures published in 2004, 31 percent of all births in the Republic of Ireland occur outside marriage. This compares with 5 percent in 1980. The average age of mothers having their first child was 30 and the fertility rate is an average of 1.98 children.

In the Republic, divorce became legal on February 27, 1997. The 2002 census showed that the number of divorced people in the state stood at 35,100, compared with 9800 in 1996. The number of separated people, including divorces, increased from 87,800 in 1996 to 133,800 in 2002. Cohabiting couples made up 8.4 percent of all family units in 2002 compared with 3.9 pecent in 1996.

Townlands, villages, parishes and counties

The Irish county structures are still of vital importance in the daily life of Irish communities. Apart from the religious significance of the parish, most rural postal addresses consist of house and townsland names. The village and parish are key focal points around which sporting rivalries and other forms of local identity are built and most people feel a strong sense of loyalty to their native county, a loyalty which also often has its clearest expression on the sports field.

Education

Particular emphasis is placed on education and literacy; 99 percent of the population aged fifteen and over can read and write. The majority of four-year-olds attend nursery school, and all five-year-olds are in primary school. The education systems are largely under the direction of the government via the Minister for Education and Science (currently Mary Hanafin, TD). Recognised primary and secondary schools must adhere to the curriculum established by authorities that have power to set them.

The education systems in Ireland are complex due to a confusion of ownership, control and curricular assessment. This has arisen because the systems developed over long periods of time with variable influence by several key players, including the Irish state. Unlike in countries such as France, Ireland's state education system is largely limited to the content of the curriculum, although this too is mediated by voluntary interests.

Primary, Secondary and Third (University/College) level education are all free in the Republic of Ireland for all EU citizens.

Ownership Technically, the majority of Ireland's primary and secondary schools are owned by the Catholic parishes of the country. Parishes establish schools and this has tended to develop where the local Catholic Church provided the land under the ownership of a Board of Management, composed of various community interests, including but not exclusively so, the local Catholic priest. With the decline in numbers of priests, this has proven more and more problematic. The parish's school is then run by the Board of Management on behalf of the local community. With increasing numbers of non-Catholics in Ireland, the question of Catholic school ethos has become contested. The State provides and pays for the teachers, organises the curriculum and agrees to provide examinations and other centralised services for these schools. At second level, the system of ownership is more complex again because schools owned by the Churches, the State and other voluntary interests coexist side by side. At this level, the parish's interests are represented by a Board of Management / Trust established by an order of the Catholic Church under the direction of a Bishop. A state owned secondary school - generally called community or comprehensive schools - is wholly controlled by the State through the Department of Education and Science. A small number of other denominational schools exist such as those organised by the Islamic communities. The church ownership model extends to these groups too.

Control Control of schools is technically vested in the Catholic Church/Church of Ireland/church grouping. As the State decides the content of educational curricula with various interests, including the Churches, control is effectively in the State's purview. Ireland's educational systems can be characterised in a largely voluntary manner. This does not imply that their effects are politically neutral with class and other interests sequentially embedded throughout each system.

Class

The Irish regard their culture as egalitarian, reciprocal, and informal. While an English-style rigid class structure is absent, social and economic class distinctions persist through educational and religious institutions, and the professions. At the top of Irish society is a class of wealthy people, who have made fortunes in business, the professions, the arts and through sport. There is a working class, and a middle class. Relative wealth and social class influence choice of school and university, which affects class mobility. Use of language, especially dialect, indicates class and other social standing. Dress codes have relaxed, but designer clothing, good food, travel, and expensive cars and houses, all reflect degrees of wealth.

Culture

Architecture

Art

Cinema

Notable Hollywood actors from the Republic of Ireland include Maureen O'Hara, Barry Fitzgerald, George Brent, Arthur Shields, Maureen O'Sullivan, Richard Harris, Peter O'Toole, Pierce Brosnan, Gabriel Byrne, Brendan Gleeson, Daniel Day Lewis (by citizenship), Colm Meaney, Colin Farrell, Jonathan Rhys-Meyers and Cillian Murphy.

The flourishing Irish film industry, state-supported by Bord Scannán na hÉireann, helped launched the careers of directors Neil Jordan and Jim Sheridan, and supported Irish films such as John Crowley's Intermission, Neil Jordan's Breakfast on Pluto, and others. A policy of tax breaks and other incentives has also attracted international film to Ireland, including Mel Gibson's Braveheart, Steven Spielberg's Saving Private Ryan.

Fillum The Irish Film industry has grown rapidly in recent years thanks largely to the promotion of the sector by Bord Scannán na hÉireann (The Irish Film Board)[2] and the introduction of heavy tax breaks. Some of the most successful Irish films included Intermission (2001), Man About Dog (2004), Michael Collins (1996), Angela's Ashes (1999) and The Commitments (1991).

Ireland has also proved a popular location for shooting films with The Quiet Man (1952), Saving Private Ryan (1998), Braveheart (1995), and King Arthur (2004) all being shot in Ireland.

Clothing

Cuisine

There are many references to food and drink in early Irish literature. Honey seems to have been widely eaten and used in the making of mead. The old stories also contain many references to banquets, although these may well be greatly exaggerated and provide little insight into everyday diet. There are also many references to fulachtaí fia, which are archaeological sites commonly believed to have once been used for cooking venison. The fulachtaí fia have holes or troughs in the ground which can be filled with water. Meat can then be cooked by placing hot stones in the trough until the water boils. Many fulachtaí fia sites have been identified across the island of Ireland, and some of them appear to have been in use up to the 17th century.

Excavations at the Viking settlement in the Wood Quay area of Dublin have produced a significant amount of information on the diet of the inhabitants of the town. The main animals eaten were cattle, sheep and pigs, with pigs being the most common. This popularity extended down to modern times in Ireland. Poultry and wild geese as well as fish and shellfish were also common, as were a wide range of native berries and nuts, especially hazel. The seeds of knotgrass and goosefoot were widely present and may have been used to make a porridge.

The potato in Ireland

The potato would appear to have been introduced into Ireland in the second half of the 17th century, initially as a garden crop. It eventually came to be the main food field crop of the tenant and labouring classes. As a food source, the potato is extremely efficient in terms of energy yielded per unit area of land. The potato is also a good source of many vitamins and minerals, particularly vitamin C (especially when fresh).

As a result, the typical 18th and 19th century Irish diet of potatoes and buttermilk was a contributing factor in the population explosion that occurred in Ireland at that time. However, the damp Irish climate favours the spread of potato blight and this frequently led to shortages and famine. The most notable instance being the Great Irish Famine (1845-1849) , which more or less undid all the growth in population of the previous century by a combination of starvation, disease and emigration.

Food in Ireland today

In the 20th century the usual modern selection of foods common to Western cultures has been adopted in Ireland. Both US fast-food culture and continental European dishes have influenced the country, along with other world dishes introduced in a similar fashion to the rest of the Western world. Common meals include pizza, curry, Chinese food, and lately, some west African dishes have been making an appearance. Supermarket shelves now contain ingredients for, among others, traditional, European, American (Mexican/Tex-Mex), Indian, Polish and Chinese dishes.

The proliferation of fast food has led to increasing public health problems including obesity, and one of the highest rates of heart disease in the world. Traditional Irish food and diet is also somewhat to blame, with a large emphasis on meat. Government efforts to combat this had included television advertisements. In the north, the Ulster Fry has been particularly cited as being a major source for a higher incidence of cardiac problems, quoted as being a "heart attack on a plate". All the ingredients are fried, although more recently the trend is to grill as many of the ingredients as possible.

In tandem with these developments, the last quarter of the century saw the emergence of a new Irish cuisine based on traditional ingredients handled in new ways. This cuisine is based on fresh vegetables, fish, especially salmon and trout, oysters and other shellfish, traditional soda bread, the wide range of hand-made cheeses that are now being made across the country, and, of course, the potato. Traditional dishes, such as the Irish stew, Dublin coddle, the Irish breakfast and potato bread, have enjoyed a resurgence. Schools like the Ballymaloe Cookery School have emerged to cater for the associated increased interest in cooking with traditional ingredients.

Pub culture