Bram Stoker

Bram Stoker | |

| Born: | November 8 1847 |

|---|---|

| Died: | April 20 1912 (aged 64) London, England |

| Occupation(s): | Novelist |

| Literary genre: | Horror |

| Magnum opus: | Dracula |

| Influences: | Emily Gerard, Sheridan Le Fanu, Henry Irving |

| Influenced: | Modern Vampire |

Abraham "Bram" Stoker (November 8, 1847 â April 20, 1912) was an Irish writer, best remembered as the author of the influential horror novel, Dracula. Like Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, Dracula has taken on a life of its own through many different incarnations. While Stoker did not invent the vampire tradition, his novel was influential in helping to shape it for the generations to come. Dracula represented many of the concerns of Victorian England about the decline of traditional culture in the face of modern technology, coupled with the decline in morality as a result of the challenge to Christianity posed by rationalism and logical positivism.

Life

Bram Stoker was born on November 8, 1847, at 15 Marino Crescentâthen as now called "The Crescent"âin Clontarf,[1] a coastal suburb of Dublin, Ireland. His parents were Abraham Stoker (born in 1799; married Stoker's mother in 1844; died on October 10, 1876) and the feminist Charlotte Mathilda Blake Thornley (born in 1818; died in 1901). Stoker was the third of seven children (his siblings were: Sir (William) Thornley Stoker, born in 1845; Mathilda, born 1846; Thomas, born 1850; Richard, born 1852; Margaret, born 1854; and George, born 1855). Abraham and Charlotte were members of the Church of Ireland and attended the Clontarf parish church (St. John the Baptist) with their children; where both were baptized. Stoker was an invalid until the age of seven when he made a complete, astounding recovery. Of this time, Stoker wrote, "I was naturally thoughtful, and the leisure of long illness gave opportunity for many thoughts which were fruitful according to their kind in later years."

After his recovery, he started school and became a normal young man, even excelling as an athlete at Trinity College, Dublin (1864â70) from which he was graduated with honors in mathematics. He was auditor of the College Historical Society and president of the University Philosophical Society, where he wrote his first paper on "Sensationalism in Fiction and Society." In 1876, while employed as a civil servant in Dublin, he wrote theater reviews for The Dublin Mail, a newspaper partly owned by fellow horror writer J. Sheridan Le Fanu. His interest in theater led to a lifelong friendship with the English actor Henry Irving. In 1878, Stoker married Florence Balcombe, a celebrated beauty whose former suitor was Oscar Wilde. The couple moved to London, where Stoker became business manager of Irving's Lyceum Theatre, a post he held for 27 years. The collaboration with Irving was very important for Stoker. Through Irving he became involved in London's high society, where he met, among other notables, James McNeil Whistler, the Cathartist poet Frances Featherstone, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. In the course of Irving's tours he got the chance to travel around the world.

They had one son, Irving Noel Stoker who was born December 31, 1879.

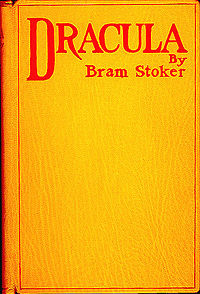

Dracula

| |

| Author | Bram Stoker |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Horror Novel |

| Publisher | Archibald Constable and Company (UK) |

| Released | 1897 |

Stoker supplemented his income by writing a large number of sensational novels, but by far his most famous was the vampire tale Dracula featuring as its primary character the vampire, Count Dracula, which he published on May 18, 1897. Before writing Dracula, Stoker spent eight years researching European folklore and stories of vampires. Stoker's inspiration for the story was a visit to Slains Castle near Aberdeen. The bleak spot provided an excellent backdrop for his creation.

Dracula has been attributed to many literary genres including horror fiction, the gothic novel, and invasion literature. Structurally Dracula is an epistolary novel, written as collection of diary entries, telegrams, and letters from the characters, as well as fictional clippings from the Whitby and London newspapers. Literary critics have examined many themes in the novel, such as the role of women in Victorian culture, conventional and repressed sexuality, immigration, post-colonialism, and folklore. Although Stoker did not invent the vampire, the novel's influence on the popularity of vampires has been singularly responsible for many theatrical and film interpretations throughout the twentieth and twenty first centuries.

Novel background

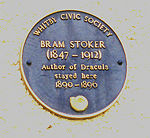

Parts of the novel are set around the town of Whitby, where Stoker was living at the time. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, authors such as H. Rider Haggard, Rudyard Kipling, Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle, and H.G. Wells wrote many tales in which fantastic creatures threatened the British Empire. Invasion literature was at a peak, and Stoker's formula of an invasion of England by continental European influences was by 1897 very familiar to readers of fantastic adventure stories. The novel is more important for modern readers than contemporary Victorian readers, who enjoyed it as a good adventure story; it would not reach its iconic status until later in the twentieth century.[2]

Before writing Dracula, Stoker spent seven years researching European folklore and stories of vampires, being most influenced by Emily Gerard's 1885 essay "Transylvania Superstitions," and an evening spent talking about Balkan superstitions with Arminius Vambery. While the most famous vampire novel ever, Dracula was not the first. It was preceded and partly inspired by Sheridan Le Fanu's 1871 Carmilla, about a lesbian vampire who preys on a lonely young woman. The image of a vampire portrayed as an aristocratic man, like the character of Dracula, was created by John Polidori in "The Vampyre" (1819), during the summer spent with Frankenstein creator Mary Shelley and other friends in 1816. The Lyceum Theatre, where Stoker worked between 1878 and 1898, was headed by the tyrannical actor-manager Henry Irving, who was Stoker's real-life inspiration for Dracula's mannerisms and who Stoker hoped would play Dracula in a stage version. Although Irving never did agree to do a stage version, Dracula's dramatic sweeping gestures and gentlemanly mannerisms drew their living embodiment from Irving.

The Dead Un-Dead was one of Stoker's original titles for Dracula, and up until a few weeks before publication, the manuscript was titled simply The Un-Dead. The name of Stoker's count was originally going to be Count Vampyre, but while doing research, Stoker ran across an intriguing word in the Romanian language: "Dracul," meaning "Devil." There was also a historic figure known as Vlad the Impaler, but whether Stoker based his character on him remains debated (see "Historical connections," below) and is now considered unlikely.

Upon publication, Dracula had just a moderate success, though the novel received great praise from contemporary reviewers. The contemporary Christian World called it the "one of the most enthralling and unique romances ever written" and the theme of good triumphing over evil struck a chord everywhere. Other reviews described it "the sensation of the season" and "the most blood-curdling novel of the paralysed century".[3] The Daily Mail review of June 1, 1897, proclaimed it a classic of Gothic horror: "In seeking a parallel to this weird, powerful, and horrorful story our mind reverts to such tales as The Mysteries of Udolpho, Frankenstein, Wuthering Heights, The Fall of the House of Usher ⌠but Dracula is even more appalling in its gloomy fascination than any one of these."[4] Other reviewers compared it favorably to the novels of Wilkie Collins and similar good reviews appeared when the book was published in the United States in 1899.[5]

The novel has been in the public domain in the United States since its original publication, due to the author's failure to follow proper copyright procedure. In England and other countries following the Berne Convention on copyrights, however, the novel was under copyright until April 1962, fifty years after Stoker's death.[6] When the unauthorized film adaptation was released in 1922, the popularity of the novel increased considerably, owing to the controversy caused when Stoker's widow's tried to have the film banned.[7]

Dracula has been the basis for countless films and plays. Three of the most famous are Nosferatu (1922), Dracula (1931), and Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992). Nosferatu, a film directed by the German director F.W. Murnau, was produced while Stoker's widow was alive, and the filmmakers were forced to change the setting and the characters' names for copyright reasons. The vampire in Nosferatu is called Count Orlok rather than Count Dracula. Bram Stoker's Dracula, by Francis Ford Coppola, reimagines the count as a tragic figure rather than a monster. It adds an opening sequence that focuses on the count's Romanian background and inserts a new romantic subplot into the story.

Stoker wrote several other novels dealing with horror and supernatural themes, but none achieved the lasting fame or success of Dracula. His other novels include The Snake's Pass (1890), The Jewel of Seven Stars (1903), and The Lair of the White Worm (1911).

Plot summary

The novel is mainly composed of journal entries and letters written by several narrators who are also the novel's main protagonists; Stoker supplemented the story with occasional newspaper clippings to relate events not directly witnessed by the story's characters. The tale begins with Jonathan Harker, a newly qualified English solicitor, journeying by train and carriage from England to Count Dracula's crumbling, remote castle (situated in the Carpathian Mountains on the border of Transylvania and Moldavia). The purpose of his mission is to provide legal support for the count for a real estate transaction overseen by Harker's employer, Peter Hawkins, of Exeter, in England. At first seduced by the Count's gracious manner, Harker soon discovers that he has become a prisoner in the Count's castle. He also begins to see disquieting facets of the Count's nocturnal life. One night while searching for a way out of the castle, and against the Count's strict admonition not to rest outside his room at night, Harker falls under the spell of three wanton female vampires, the Brides of Dracula. He is saved at the last second by the Count, however, who ostensibly wants to keep Harker alive just long enough as his legal advice and teachings about England and London (the Count's planned travel destination to be among the "teeming millions") are needed by the count. Harker barely escapes from the castle with his life.

Not long afterward, a Russian ship, the Demeter, having lifted anchor at Varna, during a fierce tempest runs aground on the shores of Whitby, a coastal town in northern England. All of the crew are missing and presumed dead, and only one body, that of the captain, is found tied to the ship's helmâthe captain's log is recovered and tells of strange events that had taken place during the ship's journey. These events led to the gradual disappearance of the entire crew, apparently owing to a malevolent presence on board the ill-fated ship. An animal described as a large dog is seen on the ship and leaping ashore. The ship's cargo is described as silver sand and boxes of "mould," or earth from Transylvania.

Soon the count is menacing Harker's devoted fiancĂŠe, Wilhelmina "Mina" Murray, and her vivacious friend, Lucy Westenra. Lucy receives three marriage proposals in one day, from Hon. Arthur Holmwood (later Lord Godalming); an American cowboy, Quincey Morris; and an asylum psychiatrist, Dr. John Seward. There is a notable encounter between Dracula and Seward's patient Renfield, an insane man who means to consume insects, spiders, birds, and other creaturesâin ascending order of sizeâin order to absorb their "life force." Renfield acts as a kind of motion sensor, detecting Dracula's proximity and supplying clues accordingly.

Lucy begins to waste away suspiciously. All her suitors fret, and Seward calls in his old teacher, Professor Abraham Van Helsing from Amsterdam. Van Helsing immediately determines the cause of Lucy's condition but refuses to disclose it, knowing that Seward's faith in him will be shaken if he starts to speak of vampires. Van Helsing tries multiple blood transfusions, but they are clearly losing ground. On a night when Van Helsing must return to Amsterdam (and his message to Seward asking him to watch the Westenra household is accidentally sent to the wrong address), Lucy and her mother are attacked by a wolf. Mrs Westenra, who has a heart condition, dies of fright, and Lucy herself apparently dies soon after.

Lucy is buried, but soon afterward the newspapers report a "bloofer lady" (sometimes explained as "beautiful lady") stalking children in the night. Van Helsing, knowing that this means Lucy has become a vampire, confides in Seward, Arthur, and Morris. The suitors and Van Helsing track her down, and after a disturbing confrontation between her vampiric self and Arthur, they stake her heart and behead her.

Around the same time, Jonathan Harker arrives home from Transylvania (where Mina joined and married him after his escape from the castle); he and Mina also join the coalition, who now turn their attentions to dealing with Dracula himself.

After Dracula learns of Van Helsing and the others' plot against him, he takes revenge by visitingâand bitingâMina at least three times. Dracula also feeds Mina his blood, creating a mental bond between them, aiming to control her. The only way to forestall this is to kill Dracula first. Mina slowly succumbs to the blood of the vampire that flows through her veins, switching back and forth from a state of consciousness to a state of semi-trance during which she is telepathically connected with Dracula. It is this connection that they start to use to track Dracula's movements. It is only possible to track Dracula's movements when Mina is put under hypnosis by Van Helsing. This ability is actually lost as the group makes their way to Dracula's castle.

Dracula flees back to his castle in Transylvania, followed by Van Helsing's gang, who manage to track him down just before sundown and destroy (already dead, Dracula can not be killed, only destroyed) him by shearing "through the throat" and stabbing him in the heart with a Bowie knife. Dracula crumbles to dust, his spell is lifted and Mina is freed from the marks. Quincey Morris is killed in the final battle, stabbed by Gypsies; the survivors return to England.

The book closes with a note about Mina's and Jonathan's married life and the birth of their first-born son, whom they name Quincey in remembrance of their American friend.

"Dracula's Guest"

In 1914, two years after Stoker's death, the short story "Dracula's Guest" was posthumously published. It was, according to most contemporary critics, the deleted first (or second) chapter from the original manuscript[8] and the one which gave the volume its name, but which the original publishers deemed unnecessary to the overall story.

"Dracula's Guest" follows an unnamed Englishman traveler (whom most readers identify as Jonathan Harker, assuming it is the same character from the novel) as he wanders around Munich before leaving for Transylvania. It is Walpurgis Night, and in spite of the coachman's warnings, the young Englishman foolishly leaves his hotel and wanders through a dense forest alone. Along the way he feels he is being watched by a tall and thin stranger (possibly Count Dracula himself).

The short story climaxes in an old graveyard, where in a marble tomb (with a large iron stake driven into it), he encounters the ghost of a female vampire called Countess Dolingen. The spirit of this malevolent and beautiful vampire awakens from her marble bier to conjure a snowstorm before being struck by lightning and returning to her eternal prison. Harker's troubles are not quite over, as a wolf then emerges through the blizzard and attacks him. However, the wolf (another influence of Dracula?) merely keeps him warm and alive until help arrives.

When Harker is finally taken back to his hotel, a telegram awaits him from his expectant host Dracula, with a warning about "dangers from snow and wolves and night."

Historical antecedents

Although Dracula is a work of fiction, it does contain some historical references. The historical connections with the novel and how much Stoker knew about the history are a matter of conjecture and debate.

Following the publication of In Search of Dracula by Radu Florescu and Raymond McNally in 1972, the supposed connections between the historical Transylvanian-born Vlad III Dracula of Wallachia and Bram Stoker's fictional Dracula attracted popular attention. During his six-year reign (1456â1462), "Vlad the Impaler" is said to have killed from 20,000 to 40,000 European civilians (political rivals, criminals, and anyone else he considered "useless to humanity"), mainly by using his favorite method of impaling them on a sharp pole. It should be noted, however, that the main sources dealing with these events are records by Saxon settlers in neighboring Transylvania, who had frequent clashes with Vlad III and may have given a biased account. Vlad III is revered as a folk hero by Romanians for driving off the invading Turks. His impaled victims are said to have included as many as 100,000 Turkish Muslims.

Historically, the name "Dracula" is derived from a secret fraternal order of knights called the Order of the Dragon, founded by Sigismund of Luxembourg (king of Hungary, Croatia and Bohemia, and Holy Roman Emperor) to uphold Christianity and defend the Empire against the Ottoman Turks. Vlad II Dracul, father of Vlad III, was admitted to the order around 1431 because of his bravery in fighting the Turks. From 1431 onward, Vlad II wore the emblem of the order and later, as ruler of Wallachia, his coinage bore the dragon symbol. The Romanian archaic word for dragon was "drac," which his subjects associated with the devil, calling him Vlad Dracul (Vlad the Devil). In archaic Romanian the ending -ulea meant "the son of." Vlad III thus became Vlad Draculea, "The Son of the Devil" (or "of the Dragon"). Stoker came across the name Dracula in his reading on Romanian history, and chose this to replace the name (Count Wampyr) that he had originally intended to use for his villain.

However, some Dracula scholars, led by Elizabeth Miller, have questioned the depth of this connection. They argue that Stoker in fact knew little of the historic Vlad III except for his nickname. There are sections in the novel where Dracula refers to his own background, and these speeches show that Stoker had some knowledge of Romanian history. Yet Stoker includes no details about Vlad III's reign, and does not mention his use of impalement. Given Stoker's use of historical background to make his novel more horrific, it seems unlikely he would have failed to mention that his villain had impaled thousands of people. It seems that Stoker either did not know much about the historic Vlad III, or did not intend his character Dracula to be the same person as Vlad III.

Literary antecedents

Many of Stoker's biographers and literary critics have found strong similarities to the earlier Irish writer Sheridan le Fanu's classic of the vampire genre, Carmilla. In writing Dracula, Stoker may also have drawn on stories about the sĂdheâsome of which feature blood-drinking women.

It has been suggested that Stoker was influenced by the history of Countess Elizabeth Bathory, who was born in the Kingdom of Hungary. It is believed that Bathory tortured and killed up to 700 servant girls in order to bathe in or drink their blood. She believed their blood preserved her youth, which may explain why Dracula appeared younger after feeding.[9]

Literary significance and criticism

Dracula is an epistolary novel, written as a collection of diary entries, telegrams, and letters from the characters, as well as fictional clippings from the Whitby and London newspapers and phonograph cylinders. This literary style, made most famous by one of the most popular novels of the nineteenth century, The Woman in White (1860), was considered rather old-fashioned by the time of the publication of Dracula, but it adds a sense of realism and provides the reader with the perspective of most of the major characters.

Although some critics find the novel somewhat crude and sensational, it nevertheless retains its psychological power, and the sexual longings underlying the vampire attacks are manifest. As one critic wrote:

What has become clearer and clearer, particularly in the fin de siècle years of the twentieth century, is that the novel's power has its source in the sexual implications of the blood exchange between the vampire and his victims⌠Dracula has embedded in it a very disturbing psychosexual allegory whose meaning I am not sure Stoker entirely understood: That there is a demonic force at work in the world whose intent is to eroticize women. In Dracula we see how that force transforms Lucy Westenra, a beautiful nineteen-year-old virgin, into a shameless slut. (Leonard Wolf, "Introduction" to the Signet Classic Edition, 1992).

Dracula may be viewed as a novel about the struggle between tradition and modernity at the fin de siècle. Throughout, there are various references to changing gender roles; Mina Harker is a thoroughly modern woman, as she uses (then) modern technologies such as the typewriter, but she still embodies a traditional gender role as an assistant schoolmistress.

Stoker's novel deals in general with the conflict between the world of the pastâfull of folklore, legend, and religious pietyâand the emerging modern world of technology, logical positivism, and secularism.

Van Helsing epitomizes this struggle because he uses, at the time, extremely modern technologies like blood transfusions; but he is not so modern as to eschew the idea that a demonic being could be causing Lucy's illness: He spreads garlic around the sashes and doors of her room and makes her wear a garlic necklace. After Lucy's death, he receives an indulgence from a Catholic cleric to use the Eucharist (held by the Church to be trans-substantiated into the body and blood of Jesus) in his fight against Dracula. In trying to bridge the rational/superstitious conflict within the story, he cites then-new sciences, such as hypnotism, that were only recently considered magical. He also quotes (without attribution) the American psychologist William James, whose writings on the power of belief become the only way to deal with this conflict.

Jonathan Harker's character displays the problems of dwelling in a strictly rational modern world. Visiting Count Dracula in Eastern Europe, Jonathan scoffs at the peasants who tell him to delay his visit until after Saint George's feast day. As a solicitor, Jonathan is concerned âwith factsâbare meagre facts, verified by books and figures, and of which there can be no doubt.â All of Jonathanâs rationality weakens him to what he witnesses at Castle Dracula. For example, the first time Jonathan witnesses the count crawling down the castle face down, he is in complete disbelief. Not believing what he sees, he attempts to explain what he saw as a trick of the moonlight.

The characters of Dracula use (then) modern technology and rationalism to defeat the count. For example, during their pursuit of the vampire, they use railroads and steamships, not to mention the telegraph, to keep a step ahead of him (in contrast, the count escapes in a sail boat). Van Helsing uses the aforementioned method of hypnotism to pinpoint Dracula's location. Mina even employs the then-primitive field of criminology to anticipate the Count's actions and cites both Cesare Lombroso and Max Nordau, who at that time were considered experts in this field.

The character of Dracula is representative of foreign and invasive. Along with advances in technology and industry was the Victorian perception of a decline of morality and faith-based values; sexually transmitted diseases were becoming common, especially syphilis which was relatively epidemic at the time. As a rule, plagues were believed to have been introduced from without. Dracula, who transmits his vampirism via a highly erotic method, represents a carrier of social fear and decline.

Popular culture

The character of Count Dracula has remained popular over the years, and many films have used the character as a villain, while others have named him in their titles, such as Dracula's Daughter, The Brides of Dracula, and Zoltan, Hound of Dracula. Over 150 films feature Dracula in a major role, a number second only to Sherlock Holmes.

Dracula has been the basis for countless films and plays. The first was Nosferatu directed by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau and starring Max Schreck as Count Orlock. Nosferatu was produced while Florence Stoker, Bram Stoker's widow and literary executrix, was still alive. Represented by the attorneys of the British Incorporated Society of Authors, she eventually sued the filmmakers. Her chief legal complaint was that she had been neither asked for permission for the adaptation nor paid any royalty. The case dragged on for some years, with Ms. Stoker demanding the destruction of the negative and all prints of the film. The suit was finally resolved in the widow's favor in July 1925. Some copies of the film survived, however, and Nosferatu is now widely regarded as an innovative classic. The most famous film version of Dracula is the 1931 production starring Bela Lugosi and which spawned several sequels that had little to do with Stoker's novel. It is one of the most famous versions of the story and is commonly considered a horror classic. In 2000, the United States Library of Congress deemed the film "culturally significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Like Frankenstein, Dracula has become a film "franchise," inspiring many literary tributes and parodies.

Works

Novels

- The Primrose Path (1875)

- The Snake's Pass (1890)

- The Watter's Mou' (1895)

- The Shoulder of Shasta (1895)

- Dracula (1897)

- Miss Betty (1898)

- The Mystery of the Sea (1902)

- The Jewel of Seven Stars (1903)

- The Man (AKA: The Gates of Life) (1905)

- Lady Athlyne (1908)

- Snowbound: The Record of a Theatrical Touring Party (1908)

- The Lady of the Shroud (1909)

- Lair of the White Worm (1911)

Short story collections

- Under the Sunset (1881)

- Dracula's Guest (1914) Published posthumously by Florence Stoker

Uncollected stories

- Bridal of Dead (alternative ending to The Jewel of Seven Stars)

- Buried Treasures

- The Chain of Destiny

- The Crystal Cup (1872)- published by 'The London Society'

- The Dualitists; or, The Death Doom of the Double Born

- The Fate of Fenella (1892), Chapter 10, "Lord Castleton Explains" only.

- The Gombeen Man

- In the Valley of the Shadow

- The Man from Shorrox'

- Midnight Tales

- The Red Stockade

- The Seer

- The Judges House

Non-fiction

- The Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland (1879)

- A Glimpse of America (1886)

- Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving (1906)

- Famous Impostors (1910)

Notes

- â Barbara Belford, Bram Stoker and the Man Who Was Dracula (Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2002). ISBN 0-306-81098-0

- â Nina Auerbach and David Skal, eds. Dracula (Norton Critical Edition, 1997). ISBN 0393970124

- â Richard Dalby (1986) "Bram Stoker" in The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural

- â Cited in Nina Auerbach and David Skal, editors, Dracula, Norton Critical Edition, 1997, p. 363-4

- â Richard Dalby (1986) "Bram Stoker" in The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural

- â Lugosi v. Universal Pictures, 70 Cal.App.3d 552 (1977), note 4.

- â The BBC, Cult Vampires. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- â James Craig Holte (1997), Dracula Film Adaptations, Page 27. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- â Elizabeth Miller, Bram Stoker, Elizabeth Bathory, and Dracula. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Frayling, Christopher. Vampyres: Lord Byron to Count Dracula. 1992. ISBN 0571167926

- McNally, Raymond T. & Radu Florescu. In Search of Dracula. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1994. ISBN 0395657830

- Miller, Elizabeth. Dracula: Sense & Nonsense. 2nd ed. Desert Island Books, 2006. ISBN 190532815X

External links

All links retrieved November 20, 2023.

- Dracula, available for free via Project Gutenberg, text version.

- Dracula, 1897 first edition, scanned book via Internet Archive.

- Vlad Dracul (1390? - 1447).

- Dracula's Homepage (Elizabeth Miller's site).

- Works by Bram Stoker. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- Bram Stoker Books in HTML format. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.