Frankenstein

| |

| Author | Mary Shelley |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Horror, Science fiction, Gothic |

| Publisher | Lackington, Hughes, Harding, Mavor & Jones |

| Released | 1 January 1818 |

| Pages | 280 |

| ISBN | NA |

Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is a novel written by the British author Mary Shelley. Shelley wrote the novel when she was 19 or 20 years old. The first edition was published anonymously in London in 1818. Shelley's name appears on the revised third edition, published in 1831. The title of the novel refers to the protagonist, a scientist named Victor Frankenstein, who learns how to create life and creates a being in the likeness of man, but larger than average and more powerful. In popular culture, people have tended to refer to the Creature as "Frankenstein," despite the fact that this was the name of the scientist, not the creature. Frankenstein is a novel infused with some elements of the Gothic novel and the Romantic movement. It was also a warning against the hubris of modern humans and the Industrial Revolution, alluded to by the novel's subtitle, The Modern Prometheus.

In mythology, Prometheus is the entity who stole fire from the gods, and was eternally punished for his pains. He usurped the role of the gods. Shelley's novel serves in part as a warning to modern man that even though tremendous scientific breakthroughs are possible, humans may not always know the full ramifications of their quest for knowledge, as Robert Oppenheimer is reported to have observed after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The story has had an influence across literature and popular culture and spawned a complete genre of horror stories and films. It is arguably considered the first fully realized science fiction novel.

Plot

The novel opens with Captain Robert Walton on his ship sailing north of the Arctic Circle. Walton's ship becomes ice-bound and he spots a figure traveling across the ice on a dog sled. Soon after, he sees an ill Victor Frankenstein, and invites him onto his ship. The narrative of Walton is a frame story that allows for the story of Victor to be related. At the same time, Walton's predicament is symbolically appropriate for Victor's tale of displaced passion and brutalism.

Victor takes over telling the story at this point. Curious and intelligent from a young age, he learns from the works of the masters of Medieval alchemy, reading such authors as Albertus Magnus, Cornelius Agrippa and Paracelsus and shunning modern Enlightenment teachings of natural science (see also Romanticism and the Middle Ages). He leaves his beloved family in Geneva, Switzerland, to study in Ingolstadt, where he is first introduced to modern science. In a moment of inspiration, combining his new-found knowledge of natural science with the alchemic ideas of his old masters, Victor perceives the means by which inanimate materials can be imbued with life. He sets about constructing a man using means that Shelley refers to only vaguely. The main idea seems to be that Victor built a complete body from various organic human parts, then simulated the functions of the human system in it. In the novel it is stated (chapter 4, volume 1) that he uses bones from charnel houses, and:

The dissecting room and the slaughterhouse furnished many of my materials; and often did my human nature turn with loathing from my occupation, whilst, still urged on by an eagerness which perpetually increased, I brought my work near to a conclusion.

Victor intended the creature to be beautiful, but when it awakens he is disgusted. As Victor used corpses as material for his creation, it has yellow, watery eyes, translucent skin, black lips, long black hair and is around 8 feet (2.4 m) in height. Victor finds this revolting and runs out of the room in terror. That night he wakes up with the creature at his bedside facing him with an outstretched arm, and flees again, whereupon the creature disappears. Shock and overwork cause Victor to become ill for several months. After recovering, in about a year's time, he receives a letter from home informing him of the murder of his youngest brother. He departs for Switzerland at once.

Near Geneva, Victor catches a glimpse of the creature in a thunderstorm among the boulders of the mountains, and is convinced that it killed his younger brother, William. Upon arriving home he finds Justine Moritz, the family's beloved maid, framed for the murder. To Victor's surprise, Justine makes a false confession because her minister threatens her with excommunication. Despite Victor's feelings of overwhelming guilt, he does not tell anyone about his horrid creation and Justine is convicted and executed. To recover from the ordeal, Victor goes hiking into the mountains where he encounters his "cursed creation" again, this time on the Mer de Glace, a glacier above Chamonix.

The creature converses with Victor and tells him his story, speaking in strikingly eloquent and detailed language. He describes his feelings first of confusion, then rejection and hate. He explains how he learned to talk by studying a poor peasant family through a chink in the wall. He secretly performed many kind deeds for this family, but in the end, they drove him away when they saw his appearance. He gets the same response from any human who sees him. The creature confesses that it was indeed he who killed William (by strangling) and framed Justine, and that he did so out of revenge. But now, the creature only wants companionship. He begs Victor to create a synthetic woman (counterpart to the synthetic man), with whom the creature can live, sequestered from all humanity but happy with his mate.

At first, Victor agrees, but later, he tears up the half-made companion in disgust and madness at the thought that the Female Creature might be just as evil as his original creation. In retribution, the creature kills Henry Clerval, Victor's best friend, and later, on Victor's wedding night, his wife Elizabeth. Soon after, Victor's father dies of grief. Victor now becomes the hunter: He pursues the creature into the Arctic ice, though in vain. Near exhaustion, he is stranded when an iceberg breaks away, carrying him out into the ocean. Before death takes him, Captain Walton's ship arrives and he is rescued.

Walton assumes the narration again, describing a temporary recovery in Victor's health, allowing him to relate his extraordinary story. Victor's health soon fails, however, and he dies. Unable to convince his shipmates to continue north and bereft of the charismatic Frankenstein, Walton is forced to turn back towards England under the threat of mutiny. Finally, the creature boards the ship and finds Victor dead, and greatly laments what he has done to his maker. He pledges to commit suicide. He leaves the ship by leaping through the cabin window onto the ice, never to be seen again.

Shelley's inspiration

How I, then a young girl, came to think of, and to dilate upon, so very hideous an idea?

The first draft of Frankenstein, along with Percy Shelley's emendations; page begins "It was on a dreary night of November that I beheld my man completed…" During the rainy summer of 1816, the "Year Without a Summer," the world was locked in a long cold volcanic winter caused by the eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815. Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, age 19, and her lover (and later husband) Percy Bysshe Shelley, visited Lord Byron at the Villa Diodati by Lake Geneva in Switzerland. The weather was consistently too cold and dreary that summer to enjoy the outdoor holiday activities they had planned, so the group retired indoors until almost dawn talking about science and the supernatural. After reading Fantasmagoriana, an anthology of German ghost stories, they challenged one another to each compose a story of their own, a contest of who could write the scariest tale. Mary conceived an idea after she fell into a waking dream or nightmare during which she saw "the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together." Byron managed to write just a fragment based on the vampire legends he heard while traveling the Balkans, and from this Polidori created The Vampyre (1819), the progenitor of the romantic vampire literary genre. Two legendary horror tales originated from this one circumstance.

Publication

Mary Shelley completed her writing in May 1817, and Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus was first published on January 1, 1818, by the small London publishing house of Harding, Mavor & Jones. It was issued anonymously, with a preface written for Mary by Percy Bysshe Shelley and with a dedication to philosopher William Godwin, her father. It was published in an edition of just 500 copies in three volumes, the standard "triple-decker" format for nineteenth century first editions. The novel had been previously rejected by Percy Bysshe Shelley's publisher, Charles Ollier and by Byron's publisher John Murray.

Critical reception of the book was mostly unfavorable, compounded by confused speculation as to the identity of the author. Sir Walter Scott wrote that "upon the whole, the work impresses us with a high idea of the author's original genius and happy power of expression," but most reviewers thought it "a tissue of horrible and disgusting absurdity" (Quarterly Review).

Despite the reviews, Frankenstein achieved an almost immediate popular success. It became widely known especially through melodramatic theatrical adaptations; Mary Shelley saw a production of Presumption; or The Fate of Frankenstein, a play by Richard Brinsley Peake, in 1823. A French translation appeared as early as 1821 (Frankenstein: ou le Prométhée Moderne, translated by Jules Saladin).

The second edition of Frankenstein was published on August 11, 1823, in two volumes (by G. and W.B. Whittaker), and this time credited Mary Shelley as the author.

On October 31, 1831, the first "popular" edition in one volume appeared, published by Henry Colburn & Richard Bentley. This edition was quite heavily revised by Mary Shelley, and included a new, longer preface by her, presenting a somewhat embellished version of the genesis of the story. This edition tends to be the one most widely read now, although editions containing the original 1818 text are still published. In fact, many scholars prefer the 1818 edition. They argue that it preserves the spirit of Shelley's original publication.[4]

Name origins

Frankenstein's creature

Part of Frankenstein's rejection of his creation is the fact that he does not give it a name, suggesting a lack of identity. Instead it is referred to by words such as "monster," "creature," "demon," "dæmon," "fiend," "demonic corpse," "the being" and "wretch." When Frankenstein converses with the monster in Chapter 10, he addresses it as "Devil," "Vile insect," "Abhorred monster," "fiend," "wretched devil," and "abhorred devil."

During a telling Shelley did of Frankenstein, she referred to the creature as "Adam." Shelley was referring to the first man in the Garden of Eden, as in her epigraph:

- Did I request thee, Maker from my clay

- To mould Me man? Did I solicit thee

- From darkness to promote me?

- John Milton, Paradise Lost (X.743-5)

The monster has often been mistakenly called "Frankenstein." In 1908, one author said, "It is strange to note how well-nigh universally the term 'Frankenstein' is misused, even by intelligent persons, as describing some hideous monster…."[5] Edith Wharton's The Reef (1916) describes an unruly child as an "infant Frankenstein."[6] David Lindsay's "The Bridal Ornament," published in The Rover, June 12, 1844, mentioned "the maker of poor Frankenstein." After the release of James Whale's popular 1931 film Frankenstein, the public at large began speaking of the monster itself as "Frankenstein." A reference to this occurs in Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and in several subsequent films in the series, as well as in film titles such as Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein.

Some justify referring to the Creature as "Frankenstein" by pointing out that the Creature is, so to speak, Victor Frankenstein's offspring. Also, one might say that the monster is the invention of Doctor Frankenstein, and inventions are often named after the person who invented them, and if one is to consider the creature his son (for he did give it life) "Frankenstein" is his familial name, and thus would also rightly belong to the creation.

Frankenstein

Mary Shelley maintained that she derived the name "Frankenstein" from a dream-vision. Despite her public claims of originality, the significance of the name has been a source of speculation. Literally, in German, the name Frankenstein means "stone of the Franks." The name is associated with various places such as Castle Frankenstein (Burg Frankenstein), which Mary Shelley had seen while on a boat before writing the novel. Frankenstein is also a town in the region of Palatinate; and before 1946, Ząbkowice Śląskie, a city in Silesia, Poland, was known as Frankenstein in Schlesien. Moreover, Frankenstein is a common family name in Germany.

More recently, Radu Florescu, in his book In Search of Frankenstein, argued that Mary and Percy Shelley visited Castle Frankenstein on their way to Switzerland, near Darmstadt along the Rhine, where a notorious alchemist named Konrad Dippel had experimented with human bodies, but that Mary suppressed mentioning this visit, to maintain her public claim of originality. A recent literary essay[7] by A.J. Day supports Florescu's position that Mary Shelley knew of, and visited Castle Frankenstein before writing her debut novel. Day includes details of an alleged description of the Frankenstein castle that exists in Mary Shelley's "lost" journals. However, this theory is not without critics; Frankenstein expert Leonard Wolf calls it an "unconvincing…conspiracy theory."[8]

Victor

A possible interpretation of the name Victor derives from Paradise Lost by John Milton, a great influence on Shelley (a quotation from Paradise Lost is on the opening page of Frankenstein and Shelley even allows the monster himself to read it). Milton frequently refers to God as "the Victor" in Paradise Lost, and Shelley sees Victor as playing God by creating life. In addition to this, Shelley's portrayal of the monster owes much to the character of Satan in Paradise Lost; indeed, the monster says, after reading the epic poem, that he empathizes with Satan's role in the story.

There are many similarities between Victor and Percy Shelley, Mary's husband. Victor was a pen name of Percy Shelley's, as in the collection of poetry he wrote with his sister Elizabeth, Original Poetry by Victor and Cazire.[9] There is speculation that one of Mary Shelley's models for Victor Frankenstein was Percy, who at Eton had "experimented with electricity and magnetism as well as with gunpowder and numerous chemical reactions," and whose rooms at Oxford were filled with scientific equipment.[10] Percy Shelley was the first-born son of a wealthy country squire with strong political connections and a descendant of Sir Brysshe Shelley, 1st Baronet of Castle Goring, and Richard Fitzalan, 10th Earl of Arundel. Victor's family is one of the most distinguished of that republic and his ancestors were counsellors and syndics. Percy had a sister named Elizabeth. Victor had an adopted sister, named Elizabeth. On February 22, 1815, Mary Shelley delivered a two-month premature baby and the baby died two weeks later. Percy did not care about the condition of this premature infant and left with Claire, Mary's stepsister, for a lurid affair. When Victor saw the creature come to life he fled the apartment.

"Modern Prometheus"

The Modern Prometheus is the novel's subtitle (though some modern publishings of the work now drop the subtitle, mentioning it only in an introduction). Prometheus, in some versions of Greek mythology, was the Titan who created mankind. It was also Prometheus who took fire from heaven and gave it to man. Zeus eternally punished Prometheus by fixing him to a rock where each day a predatory bird came to devour his liver, only for the liver to regrow the next day; ready for the bird to come again.

Prometheus was also a myth told in Latin but was a very different story. In this version Prometheus makes man from clay and water. Both versions suggest important themes in the novel.

Prometheus' relation to the novel can be interpreted in a number of ways. The Titan in the Greek mythology of Prometheus parallels Victor Frankenstein. The godlike Victor rebels against the laws of nature by creating life and as a result is punished by his creation. Victor steals the secret of creation from God just as the Titan stole fire from heaven to give to man. Victor is reprimanded by suffering the loss of those close to him and having the dread of himself getting killed by his creation.

For Mary Shelley, Prometheus was not a hero but a devil, whom she blamed for bringing fire to man and thereby seducing the human race to the vice of eating meat (fire brought cooking which brought hunting and killing).[11] Support for this claim may be reflected in Chapter 17 of the novel, where the monster speaks to Victor Frankenstein: "My food is not that of man; I do not destroy the lamb and the kid to glut my appetite; acorns and berries afford me sufficient nourishment." For Romance era artists in general, Prometheus' gift to man compared with the two great utopian promises of the eighteenth century: The Industrial Revolution and the French Revolution, containing both great promise and potentially unknown horrors.

Byron was particularly attached to the play Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus, and Percy Shelley would soon write his own Prometheus Unbound (1820). The term "Modern Prometheus" was actually coined by Immanuel Kant, referring to Benjamin Franklin and his then recent experiments with electricity.[12]

Shelley's sources

Mary incorporated a number of different sources into her work, not the least of which was the Promethean myth from Ovid. The influence of John Milton's Paradise Lost and Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, the books the Creature finds in the cabin, are also clearly evident within the novel. Also, both Shelleys had read William Thomas Beckford's Gothic novel Vathek. Frankenstein also contains multiple references to her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, and her major work, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, which discusses the lack of equal education for males and females. The inclusion of her mother's ideas in her work is also related to the theme of creation and motherhood in the novel. Mary is likely to have acquired some ideas for Frankenstein's character from Humphry Davy's book Elements of Chemical Philosophy in which he had written that "science has…bestowed upon man powers which may be called creative; which have enabled him to change and modify the beings around him…."

Analysis

One interpretation of her novel was alluded to by Shelley herself, in her account of the radical politics of her father, William Godwin:

The giant now awoke. The mind, never torpid, but never rouzed to its full energies, received the spark which lit it into an unextinguishable flame. Who can now tell the feelings of liberal men on the first outbreak of the French Revolution. In but too short a time afterwards it became tarnished by the vices of Orléans—dimmed by the want of talent of the Girondists—deformed and blood-stained by the Jacobins.[13]

The book can be seen as a criticism of scientists who are unconcerned by the potential consequences of their work. Victor was heedless of those dangers, and irresponsible with his invention. Instead of immediately destroying the evil he had created, he was overcome by fear and fell psychologically ill. During Justine's trial for murder, he had the chance to perhaps save the young girl by revealing that a violent man had recently declared a vendetta against him and his loved ones. Instead, Frankenstein indulges in his own self-centered grief. The day before Justine is executed and thus resigns herself to her fate and departure from the "sad and bitter world," his sentiments are as such:

The poor victim, who was on the morrow to pass the awful boundary between life and death, felt not, as I did, such deep and bitter agony… The tortures of the accused did not equal mine; she was sustained by innocence, but the fangs of remorse tore my bosom and would not forego their hold.

It is noteworthy, however, that Frankenstein, despite his colossal folly at creating his monster, did realize the foolishness of his actions. In Chapter 24, he warns Walton of the danger inherent in tampering with such evil. "Learn from my miseries and do not seek to increase your own." These are the words he uses to potentially redeem some part of himself, as well as prevent further evil from occurring.

Representing a minority opinion, Arthur Belefant in his book, Frankenstein, the Man and the Monster (1999, ISBN 0-9629555-8-2) contends that Mary Shelley's intent was for the reader to understand that the Creature never existed, and Victor Frankenstein committed the three murders. In this interpretation, the story is a study of the moral degradation of Victor, and the science fiction aspects of the story are Victor's imagination.

Frankenstein in popular culture

Shelley's Frankenstein has been called the first novel of the now-popular mad scientist genre.[14] However, popular culture has changed the naive, well-meaning Victor Frankenstein into more and more of a corrupt character. It has also changed the creature into a more sensational, dehumanized being than was originally portrayed. In the original story, the worst thing that Victor does is to neglect the creature out of fear. He does not intend to create a horror. The creature, even, begins as an innocent, loving being. Not until the world inflicts violence on him does he develop his hatred. Scientific knowledge is highlighted at the end by Victor as potentially evil and dangerously alluring.[15]

Soon after the book was published, however, stage managers began to see the difficulty of bringing the story into a more visual form. In performances beginning in 1823, playwrights began to recognize that to visualize the play, the internal reasonings of the scientist and the creature would have to be cut. The creature became the star of the show, with his more visual and sensational violence. Victor was portrayed as a fool for delving into nature's mysteries. Despite the changes, though, the play was much closer to the original than later films would be.[16] Comic versions also abounded, and a musical burlesque version was produced in London, in 1887, called Frankenstein, or The Vampire's Victim.

Silent films continued the struggle to bring the story alive. Early versions, such as the Edison Company's Frankenstein, managed to stick somewhat close to the plot. In 1931, however, James Whale created a film that drastically changed the story. Working under Universal Studios, Whale introduced to the plot several elements now familiar to a modern audience: The image of "Dr." Frankenstein, whereas earlier he was merely a naive, young student, an Igor-like character (called Fritz in this film) who makes the mistake of bringing his master a criminal's brain while gathering body parts, and a sensational creation scene focusing on electric power rather than chemical processes. In this film, the scientist is an arrogant, intelligent, grown man, rather than a unknowing youngster. Another scientist volunteers to destroy the creature for him, the film never forcing him to take responsibility for his acts. Whale's sequel Bride of Frankenstein (1935), and later sequels Son of Frankenstein (1939), and Ghost of Frankenstein (1942) all continued the general theme of sensationalism, horror, and exaggeration, with the newly-dubbed Dr. Frankenstein and his parallels growing more and more sinister.[17]

Later films diverted even more from Shelley's story, portraying the doctor as a sexual pervert and using his new persona to ask contemporary questions about science. Andy Warhol's Frankenstein portrayed him as a necrophiliac, and in The Rocky Horror Picture Show Dr. Frank-N-Furter (a parody of Frankenstein) creates a creature as a blond adonis for use as a sexual plaything. In Frankenstein Created Woman, he transplants a man's soul into a woman's body, joining the transsexual debate. And in Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed, he transplants a fellow-scientist's brain into another body in order to keep him alive, introducing moral questions into how far science should go to save a life. Although these films managed to bring the audience's attention back to the scientist, rather than the monster, they continue to show him as more depraved than the original. Overall, the story of Frankenstein that most people know today is more the product of movie studios than of Mary Shelley. Still, these films have provided valuable insights into the nature of film, the evolution of the general populace's view of science, and several interesting interpretations of a classic story.[18]

Mel Brooks' Young Frankenstein is a spoof of Frankenstein in which Victor Frankenstein's grandson, Frederick Frankenstein returns to settle his grandfather's affairs and ends up creating a new creature. The film is set in Transylvania, a region of Romania that was the original setting of Dracula.

Although the morals of Shelley's story may not have been passed down along with the rest of her tale, Frankenstein has become a very popular story being told in today's society. It is often common to see Frankenstein's monster appear in movies, music, readings, and even at the door step on Halloween. Though the tale's details have been slightly changed as it has passed from generation to generation, the overall concept of her story remains and continues being carried and passed throughout history.

See also

- Homunculus

- Golem

Notes

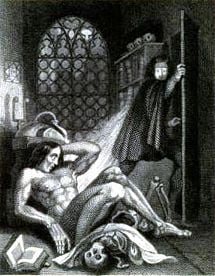

- ↑ This illustration is reprinted in the frontpiece to the 2008 edition of Frankenstein Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ National Library of Medicine, Frankenstein:Celluloid Monster, National Institutes of Health. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ National Library of Medicine, Frankenstein: Celluloid Monster. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ Anne K. Mellor, "Choosing a Text of Frankenstein to Teach," in W.W. Norton Critical edition.

- ↑ Google Books, Author's Digest: The World's Great Stories in Brief. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ The Reef, 96.

- ↑ Fantasmagoriana.

- ↑ Leonard Wolf, 20.

- ↑ Mark Sandy, Original Poetry by Victor and Cazire, The Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ Dickinson College, Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822), Department of English. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ Leonard Wolf, 20.

- ↑ The Royal Society, "Benjamin Franklin in London." Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, "Life of William Godwin," 151.

- ↑ Christopher P. Toumey, "The Moral Character of Mad Scientists: A Cultural Critique of Science," Science, Technology, & Human Values 17.4 (Autumn, 1992): 8.

- ↑ Toumey, 423-425.

- ↑ Toumey, 425.

- ↑ Toumey, 425-427.

- ↑ Toumey, 428-429.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aldiss, Brian W. "On the Origin of Species: Mary Shelley." Speculations on Speculation: Theories of Science Fiction. James Gunn and Matthew Candelaria (eds.). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 2005. ISBN 978-0810849020.

- Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0198117261.

- Bann, Stephen (ed.). "Frankenstein": Creation and Monstrosity. London: Reaktion, 1994. ISBN 978-0948462603.

- Behrendt, Stephen C. (ed.). Approaches to Teaching Shelley's "Frankenstein". New York: MLA, 1990. ISBN 978-0873525398.

- Bennett, Betty T. and Stuart Curran (eds.). Mary Shelley in Her Times. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0801863349.

- Bohls, Elizabeth A. "Standards of Taste, Discourses of 'Race', and the Aesthetic Education of a Monster: Critique of Empire in Frankenstein." Eighteenth-Century Life 18.3 (1994): 23-36. ISSN 0098-2601.

- Botting, Fred. Making Monstrous: "Frankenstein," Criticism, Theory. Manchester Univ Pr, 1991. ISBN 978-0719036088.

- Clery, E. J. Women's Gothic: From Clara Reeve to Mary Shelley. Plymouth: Northcote House, 2000. ISBN 978-0746308721.

- Conger, Syndy M., Frederick S. Frank, and Gregory O'Dea (eds.). Iconoclastic Departures: Mary Shelley after "Frankenstein": Essays in Honor of the Bicentenary of Mary Shelley's Birth. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0838636848.

- Donawerth, Jane. Frankenstein's Daughters: Women Writing Science Fiction. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1997. ISBN 9780815603955

- Dunn, Richard J. "Narrative Distance in Frankenstein." Studies in the Novel 6 (1974): 408-17.

- Eberle-Sinatra, Michael (ed.). Mary Shelley's Fictions: From "Frankenstein" to "Falkner". New York: St. Martin's Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0312237189.

- Ellis, Kate Ferguson. The Contested Castle: Gothic Novels and the Subversion of Domestic Ideology. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0252060489

- Forry, Steven Earl. Hideous Progenies: Dramatizations of "Frankenstein" from Mary Shelley to the Present. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0812281316.

- Freedman, Carl. "Hail Mary: On the Author of Frankenstein and the Origins of Science Fiction." Science Fiction Studies 29.2 (2002): 253-64. ISSN 00917729.

- Gigante, Denise. "Facing the Ugly: The Case of Frankenstein." ELH 67.2 (2000): 565-87. ISSN 00138304.

- Gilbert, Sandra, and Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980. ISBN 978-0300025392.

- Heffernan, James A. W. "Looking at the Monster: Frankenstein and Film." Critical Inquiry 24.1 (1997): 133-58. ISSN 0093-1896.

- Hodges, Devon. "Frankenstein and the Feminine Subversion of the Novel." Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature 2.2 (1983): 155-64. ISSN 0732-7730.

- Hoeveler, Diane Long. Gothic Feminism: The Professionalization of Gender from Charlotte Smith to the Brontës. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0271018096.

- Knoepflmacher, U. C. and George Levine (eds.). The Endurance of "Frankenstein": Essays on Mary Shelley's Novel. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0520036123.

- Lew, Joseph W. "The Deceptive Other: Mary Shelley's Critique of Orientalism in Frankenstein." Studies in Romanticism 30.2 (1991): 255-83. ISSN 0039-3762.

- London, Bette. "Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, and the Spectacle of Masculinity." PMLA 108.2 (1993): 256-67. ISSN 0030-8129.

- Mellor, Anne K. Mary Shelley: Her Life, Her Fiction, Her Monsters. Routledge, 1989. ISBN 978-0415901475.

- Miles, Robert. Gothic Writing 1750-1820: A Genealogy. London: Routledge, 1993. ISBN 978-0415077484.

- O'Flinn, Paul. "Production and Reproduction: The Case of Frankenstein." Literature and History 9.2 (1983): 194-213. ISSN 03061973.

- Poovey, Mary. The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer: Ideology as Style in the Works of Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley, and Jane Austen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0226675282

- Rauch, Alan. "The Monstrous Body of Knowledge in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein." Studies in Romanticism 34.2 (1995): 227-53.

- Selbanev, Xtopher. Natural Philosophy of the Soul. Western Press, 1999. ISSN 0039-3762.

- Schor, Esther, (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Mary Shelley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0521007702.

- Smith, Johanna M. (ed.). Frankenstein. Case Studies in Contemporary Criticism. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 1992. OCLC 150106755.

- Stableford, Brian. "Frankenstein and the Origins of Science Fiction." Anticipations: Essays on Early Science Fiction and Its Precursors. Ed. David Seed. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0815626404.

- Tropp, Martin. Mary Shelley's Monster. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1976. ISBN 978-0395240663.

- Williams, Anne. The Art of Darkness: A Poetics of Gothic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0226899077.

External links

All links retrieved April 9, 2024.

- Online Sparknotes for Frankenstein

- Frankenstein, The Pennsylvania Electronic Edition, annotated edition containing critical articles and other resources.

- Frankenstein, 1831 illustrated edition, scanned book via Internet Archive, includes preface.

- Frankenstein, available for free via Project Gutenberg, omits the preface, edition unknown.

- Frankenstein audiobook from LibriVox, no preface and no edition information.

- Frankenstein, Online Literature Library, includes the preface, no edition information.

| ||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.