North Carolina

Template:US state

North Carolina is a state located on the Atlantic Seaboard in the southeastern United States. North Carolina was one of the original Thirteen Colonies that declared their independence from Great Britain. It seceded from the Union during the American Civil War. The state was the location of the first successful controlled, powered and sustained heavier-than-air flight, by the Wright brothers near Kitty Hawk in 1903. Today, it is a fast-growing state with an increasingly diverse economy and population. Recognizing eight Native American tribes, North Carolina has the largest population of American Indians of any state east of the Mississippi.

A nationally-famous cuisine from North Carolina is pork barbecue. However, there are strong regional differences and rivalries over the sauces and method of preparation used in making the barbecue.

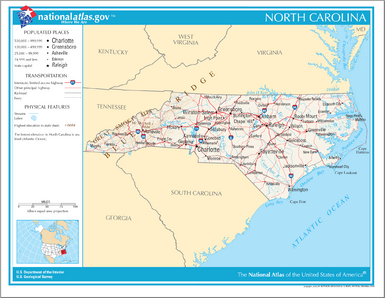

Geography

.

North Carolina is bordered by South Carolina on the south, Georgia on the southwest, Tennessee on the west, Virginia on the north, and the Atlantic Ocean on the east.

North Carolina consists of three main geographic sections: the coastal plain, which occupies the eastern 45 percent of the state; the Piedmont region, which contains the middle 35 percent; and the Appalachian Mountains and foothills. The extreme eastern section of the state contains the Outer Banks, a string of sandy, narrow islands that form a barrier between the Atlantic Ocean and inland waterways. The Outer Banks form two sounds—Albemarle Sound in the north and Pamlico Sound in the south. They are the two largest landlocked sounds in the United States. Immediately inland, the coastal plain is relatively flat, with rich soils ideal for growing tobacco, soybeans, melons, and cotton. The coastal plain is North Carolina's most rural section, with few large towns or cities. Agriculture remains an important industry.

The Piedmont is the state's most urbanized and densely populated section; all five of the state's largest cities are located in there. It consists of gently rolling countryside broken by hills or low mountain ridges. A number of small, isolated, and deeply eroded mountain ranges and peaks are located in the Piedmont. The Piedmont ranges from about 300–400 feet (90–120 m) elevation in the east to over 1,000 feet (300 m) in the west. Due to the rapid population growth of the Piedmont, many of the farms and much of the rural countryside in this region are being replaced by suburbanization: shopping centers, housing developments, and large corporate office parks.

The western section of the state is part of the Appalachian Mountain range. Among the subranges of the Appalachians located in the state are the Great Smoky Mountains, Blue Ridge Mountains, Great Balsam Mountains, Pisgah Mountains, and the Black Mountains. The Black Mountains, the highest in the Eastern United States, culminate in Mount Mitchell at 6,684 feet (2,037 m).[1], which is the highest point east of the Mississippi River. Although agriculture remains important, tourism has become the dominant industry in the mountains. One agricultural pursuit which has prospered and grown in recent decades is the growing and selling of Christmas trees. Due to the higher altitude of the mountains, the climate often differs markedly from the rest of the state.

Climate

The coastal plain is influenced by the Atlantic Ocean, which keeps temperatures mild in winter and moderate in the summer. The Atlantic Ocean has less influence on the Piedmont region, and as a result the Piedmont has hotter summers and colder winters than the coast. Annual precipitation and humidity is lower in the Piedmont than either the mountains or the coast.

The Appalachian Mountains are the coolest area of the state. Winters in western North Carolina typically feature significant snowfall and subfreezing temperatures more akin to a midwestern state than a southern one. Relatively cool summers have temperatures rarely rising above 80 °F (26.7 °C).

Severe weather occurs regularly in North Carolina. On average, the state receives a direct hit from a hurricane once a decade. Tropical storms arrive every three or four years. Only Florida and Louisiana are hit by hurricanes more often. On average, North Carolina has 50 days of thunderstorm activity per year, with some storms becoming severe enough to produce hail and damaging winds. In 1989 Hurricane Hugo caused heavy damage in Charlotte and even as far inland as the Blue Ridge Mountains.

North Carolina averages fewer than 20 tornadoes per year. Many of these are produced by hurricanes or tropical storms along the coastal plain. Tornadoes from thunderstorms are a risk, especially in the eastern part of the state.

History

Native Americans, Lost Colonies and Permanent Settlement

North Carolina was originally inhabited by many different native peoples, including those of the ancient Mississippian culture established by 1000 C.E. in the Piedmont. Historically documented tribes included Cherokee, Tuscarora, Cheraw, Pamlico, Meherrin, Coree, Machapunga, Cape Fear Indians, Waxhaw, Saponi, Tutelo, Waccamaw, Coharie, and Catawba.

Spanish explorers traveling inland encountered the last of the Mississippian culture at Joara, near present-day Morganton. Records of Hernando de Soto attested to his meeting with them in 1540. In 1567 Captain Juan Pardo led an expedition into the interior of North Carolina on a journey to claim the area for the Spanish colony, as well as establish another route to protect silver mines in Mexico (the Spanish did not realize the distances involved.) Pardo made a winter base at Joara, which he renamed Cuenca. The expedition built Fort San Juan and left 30 men, while Pardo traveled further, establishing five other forts. He returned by a different route to Santa Elena on Parris Island, South Carolina, then a center of Spanish Florida. In the spring of 1568, natives killed all the soldiers and burned the six forts in the interior, including the one at Fort San Juan. The Spanish never returned to the interior to press their colonial claim, but this marked the first European attempt at colonization of the interior of what became the United States. A journal by Pardo's scribe Bandera and archaeological findings at Joara have confirmed the settlement.[2][3]

In 1584, Elizabeth I, granted a charter to Sir Walter Raleigh, for whom the state capital is named, for land in present-day North Carolina (then Virginia).[4] Raleigh established two colonies on the coast in the late 1580s, both ending in failure. It was the second American territory the British attempted to colonize. The demise of one, the "Lost Colony" of Roanoke Island, remains one of the great mysteries of American history. Virginia Dare, the first English child to be born in North America, was born on Roanoke Island on August 18, 1587. Dare County is named for her.

As early as 1650, colonists from the Virginia colony moved into the area of Albemarle Sound. By 1663, King Charles II of England granted a charter to establish a new colony on the North American continent which generally established its borders. He named it Carolina in honor of his father Charles I.[5] By 1665, a second charter was issued to attempt to resolve territorial questions. In 1710, due to disputes over governance, the Carolina colony began to split into North Carolina and South Carolina. The latter became a crown colony in 1729.

Colonial Period and Revolutionary War

The first permanent European settlers of North Carolina were British colonists who migrated south from Virginia, following a rapid growth of the colony and the subsequent shortage of available farmland. Nathaniel Batts was documented as one of the first of these Virginian migrants. He settled south of the Chowan River and east of the Great Dismal Swamp in 1655.[6] By 1663, this northeastern area of the Province of Carolina, known as the Albemarle Settlements, was undergoing full-scale British settlement.[7] During the same period, the English monarch Charles II gave the province to the Lords Proprietors, a group of noblemen who had helped restore Charles to the throne in 1660. The new province of "Carolina" was named in honor and memory of King Charles I (Latin: Carolus). In 1712, North Carolina became a separate colony. With the exception of the Earl Granville holdings, it became a royal colony seventeen years later.[8]

Differences in the settlement patterns of eastern and western North Carolina, or the low country and uplands, affected the political, economic, and social life of the state from the eighteenth until the twentieth century. The Tidewater in eastern North Carolina was settled chiefly by immigrants from England and the Scottish Highlands. The upcountry of western North Carolina was settled chiefly by Scots-Irish and German Protestants, the so-called "cohee." Arriving during the mid-to-late 18th century, the Scots-Irish from Ireland were the largest immigrant group before the Revolution. During the Revolutionary War, the English and Highland Scots of eastern North Carolina tended to remain loyal to the British Crown, because of longstanding business and personal connections with Great Britain. The Scots-Irish and German settlers of western North Carolina tended to favor American independence from Britain.

Most of the English colonists arrived as indentured servants, hiring themselves out as laborers for a fixed period to pay for their passage. In the early years the line between indentured servants and African slaves or laborers was fluid. Some Africans were allowed to earn their freedom before slavery became a lifelong status. Most of the free colored families formed in North Carolina before the Revolution were descended from relationships or marriages between free white women and enslaved or free African or African-American men. Many had migrated or were descendants of migrants from colonial Virginia.[9] As the flow of indentured laborers to the colony decreased with improving economic conditions in Great Britain, more slaves were imported and the state's restrictions on slavery hardened. The economy's growth and prosperity was based on slave labor, devoted first to the production of tobacco.

On April 12, 1776, the colony became the first to instruct its delegates to the Continental Congress to vote for independence from the British crown, through the Halifax Resolves passed by the North Carolina Provincial Congress. The dates of both of these independence-related events are memorialized on the state flag and state seal.[10] Throughout the Revolutionary War, fierce guerilla warfare erupted between bands of pro-independence and pro-British colonists. In some cases the war was also an excuse to settle private grudges and rivalries. A major American victory in the war took place at King's Mountain along the North Carolina–South Carolina border. On October 7, 1780 a force of 1000 mountain men from western North Carolina (including what is today the State of Tennessee) overwhelmed a force of some 1000 British troops led by Major Patrick Ferguson. Most of the British soldiers in this battle were Carolinians who had remained loyal to the British Crown (they were called "Tories"). The American victory at Kings Mountain gave the advantage to colonists who favored American independence, and it prevented the British Army from recruiting new soldiers from the Tories.

The road to Yorktown and America's independence from Great Britain led through North Carolina. As the British Army moved north from victories in Charleston and Camden, South Carolina, the Southern Division of the Continental Army and local militia prepared to meet them. Following General Daniel Morgan's victory over the British Cavalry Commander Banastre Tarleton at the Battle of Cowpens on January 17, 1781, southern commander Nathanael Greene led British Lord Charles Cornwallis across the heartland of North Carolina, and away from Cornwallis's base of supply in Charleston, South Carolina. This campaign is known as "The Race to the Dan" or "The Race for the River."[8]

Generals Greene and Cornwallis finally met at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in present-day Greensboro on March 15, 1781. Although the British troops held the field at the end of the battle, their casualties at the hands of the numerically superior American Army were crippling. Following this "Pyhrric victory," Cornwallis chose to move to the Virginia coastline to get reinforcements, and to allow the Royal Navy to protect his battered army. This decision would result in Cornwallis's eventual defeat at Yorktown, Virginia later in 1781. The Patriots' victory there guaranteed American independence.

Antebellum Period

On November 21, 1789, North Carolina became the twelfth state to ratify the Constitution. In 1840, it completed the state capitol building in Raleigh, still standing today. Most of North Carolina's slave owners and large plantations were located in the eastern portion of the state. Although North Carolina's plantation system was smaller and less cohesive than those of Virginia, Georgia or South Carolina, there were significant numbers of planters concentrated in the counties around the port cities of Wilmington and Edenton, as well as suburban planters around the cities of Raleigh, Charlotte and Durham. Planters owning large estates wielded significant political and socio-economic power in antebellum North Carolina, often to the derision of the generally non-slave holding "yeoman" farmers of Western North Carolina. In mid-century, the state's rural and commercial areas were connected by the construction of a 129–mile (208 km) wooden plank road, known as a "farmer's railroad," from Fayetteville in the east to Bethania (northwest of Winston-Salem).[8]

In addition to slaves, there were a number of free people of color in the state. Most were descended from free African Americans who had migrated along with neighbors from Virginia during the eighteenth century. After the Revolution, Quakers and Mennonites worked to persuade slaveholders to free their slaves. Enough were inspired by their efforts and the language of men's rights, and arranged for manumission of their slaves. The number of free people of color rose in the first couple of decades after the Revolution.[11]

On October 25, 1836 construction began on the Wilmington and Raleigh Railroad[12] to connect the port city of Wilmington with the state capital of Raleigh. In 1849 the North Carolina Railroad was created by act of the legislature to extend that railroad west to Greensboro, High Point, and Charlotte. During the Civil War the Wilmington-to-Raleigh stretch of the railroad would be vital to the Confederate war effort; supplies shipped into Wilmington would be moved by rail through Raleigh to the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia.

During the antebellum period North Carolina was an overwhelmingly rural state, even by Southern standards. In 1860 only one North Carolina town, the port city of Wilmington, had a population of more than 10,000. Raleigh, the state capital, had barely more than 5,000 residents.

While slaveholding was slightly less concentrated than in some Southern states, according to the 1860 census, more than 330,000 people, or 33% of the population of 992,622 were enslaved African Americans. They lived and worked chiefly on plantations in the eastern Tidewater. In addition, 30,463 free people of color lived in the state. They were also concentrated in the eastern coastal plain, especially at port cities such as Wilmington and New Bern where they had access to a variety of jobs. Free African Americans were allowed to vote until 1835, when the state rescinded their suffrage.

American Civil War

In 1860, North Carolina was a slave state, in which about one-third of the population of 992,622 were enslaved African Americans. This was a smaller proportion than many Southern states. In addition, the state had a substantial number of Free Negroes, just over 30,000.[13] The state did not vote to join the Confederacy until President Abraham Lincoln called on it to invade its sister-state, South Carolina, becoming the last state to join the Confederacy. North Carolina was the site of few battles, but it provided at least 125,000 troops to the Confederacy— far more than any other state. Approximately 40,000 of those troops never returned home, dying of disease, battlefield wounds, and starvation. Elected in 1862, Governor Zebulon Baird Vance tried to maintain state autonomy against Confederate President Jefferson Davis in Richmond.

Even after secession, some North Carolinians refused to support the Confederacy. This was particularly true of non-slave-owning farmers in the state's mountains and western Piedmont region. Some of these farmers remained neutral during the war, while some covertly supported the Union cause during the conflict. Even so, Confederate troops from all parts of North Carolina served in virtually all the major battles of the Army of Northern Virginia, the Confederacy's most famous army. Five regiments from North Carolina served in the western theater in the Army of Tennessee. About two thousand North Carolinans from the western part of the state enlisted into the Union army, among the regiments they were assigned to were the 2nd and 3rd North Carolina Mounted Infantry regiments, and some in the 13th Tennessee Cavalry. Two other Union regiments made up of North Carolinians, the 1st and 2nd North Carolina U.S., were organized in the coastal areas of the state. The largest battle fought in North Carolina was at Bentonville, which was a futile attempt by Confederate General Joseph Johnston to slow Union General William Tecumseh Sherman's advance through the Carolinas in the spring of 1865.[8] In April 1865 after losing the Battle of Morrisville, Johnston surrendered to Sherman at Bennett Place, in what is today Durham, North Carolina. This was the last major Confederate Army to surrender. North Carolina's port city of Wilmington was the last Confederate port to fall to the Union. It fell in the spring of 1865 after the nearby Second Battle of Fort Fisher.

Economy

According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the state's 2006 total gross state product was $375 billion.[14] Its 2005 per capita personal income was $31,029, 36th in the nation.[15] North Carolina's agricultural outputs include poultry and eggs, tobacco, hogs, milk, nursery stock, cattle, sweet potatoes, and soybeans. However, North Carolina has recently been affected by offshoring and industrial growth in countries like China; one in five manufacturing jobs in the state has been lost to overseas competition.[16] There has been a distinct difference in the economic growth of North Carolina's urban and rural areas. While large cities such as Charlotte, Raleigh, Greensboro, and others have experienced rapid population and economic growth over the last thirty years, many of the state's small towns have suffered from loss of jobs and population. Most of North Carolina's small towns historically developed around textile and furniture factories. As these factories closed and moved to low-wage markets in Asia and Latin America, the small towns that depended upon them have suffered.

The first gold nugget found in the U.S. was found in Cabarrus County in 1799. The first gold dollar minted in the U.S. was minted at the Bechtler Mint in Rutherford County.

Agriculture and Manufacturing

Over the past century, North Carolina has grown to become a national leader in agriculture, financial services, and manufacturing. The state's industrial output—mainly textiles, chemicals, electrical equipment, paper and pulp/paper products—ranked eighth in the nation in the early 1990s. The textile industry, which was once a mainstay of the state's economy, has been steadily losing jobs to producers in Latin America and Asia for the past 25 years, though the state remains the largest textile employer in the United States.[17] Over the past few years, another important Carolina industry, furniture production, has also been hard hit by jobs moving to Asia (especially China). Tobacco, one of North Carolina's earliest sources of revenue, remains vital to the local economy, although concern about whether the federal government will continue to support subsidies for tobacco farmers has led some growers to switch to other crops like wine or leave farming altogether.[18] North Carolina is the leading producer of tobacco in the country.[19] Agriculture in the western counties of North Carolina is presently experiencing a revitalization coupled with a shift to niche marketing, fueled by the growing demand for organic and local products.

Finance, technology and research

Charlotte, North Carolina's largest city, continues to experience rapid growth, in large part due to the banking & finance industry. Charlotte is now the second largest banking center in the United States (after New York).

The information and biotechnology industries have been steadily on the rise since the creation of the Research Triangle Park (RTP) in the 1950s. Located between Raleigh and Durham, its proximity to local research universities has no doubt helped to fuel growth.

The North Carolina Research Campus underway in Kannapolis (approx. 30 miles (48 km) northeast of Charlotte) promises to enrich and bolster the Charlotte area in the same way that RTP changed the Raleigh-Durham region.[20] Encompassing 5,800,000 square feet (540,000 m²), the complex is a collaborative project involving Duke University, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and N.C. State University, along with private and corporate investors and developers.

Politics and government

The governor, lieutenant governor, and eight elected executive department heads form the Council of State. Ten other executive department heads appointed by the governor form the North Carolina Cabinet. The state's current governor is Democrat Mike Easley.

The North Carolina General Assembly, or Legislature, consists of two houses: a 50-member Senate and a 120-member House of Representatives. The Supreme Court of North Carolina is the state's highest appellate court. North Carolina currently has 13 congressional districts, which, when combined with its two U.S. Senate seats, gives the state 15 electoral votes.

Although once part of the "Solid Democratic South", by the mid-20th century Republicans began to attract white voters in North Carolina and other Southern states. The late Senator Jesse Helms played a major role in renewing the Republican Party and turning North Carolina into a two-party state. Under his banner, many conservative white Democrats in the central and eastern parts of North Carolina began to vote Republican, at least in national elections. In part, this was due to dissatisfaction with the national Democratic Party's stance on issues of civil rights and racial integration. In later decades, conservatives rallied to Republicans over social issues such as prayer in school, gun rights, abortion rights, and gay rights.

Except for regional son Jimmy Carter's election in 1976, from 1968–2004 North Carolina has voted Republican in every presidential election. At the state level, however, the Democrats still control most of the elected offices. State and local elections have become highly competitive compared to the previous one-party decades of the 20th century.

Modern North Carolina politics center less around the old east-west geographical split, and more on a growing urban-suburban-rural divide. Many of the state's rural and small-town areas are now heavily Republican, while growing urban centers such as Charlotte, Asheville, Raleigh, Durham and Greensboro are increasingly Democratic. The suburban areas around the cities usually hold the power, and vote both ways.

North Carolina remains a control state. This is probably due to the state's strongly conservative Protestant heritage. Four of the state's counties - Clay, Graham, Mitchell, and Yancey, which are all located in rural areas - remain "dry" (the sale of alcoholic beverages is illegal).[2] However, the remaining 96 North Carolina counties allow the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages. Even in rural areas, the opposition to selling and drinking alcoholic beverages is declining.

North Carolina is one of the 12 states to decriminalize marijuana. In 1997 Marijuana and Tetrahydrocannabinols were moved from a schedule I to schedule IV . Transfer of less than 5 grams is not considered sale, and up to 1 1/2 ounces is a misdemeanor punishable by a fine or community service, at the judge's discretion, rather than imprisonment or a felony charge.[21]

Demographics

| Historical populations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 393,751 | ||

| 1800 | 478,103 | 21.4% | |

| 1810 | 556,526 | 16.4% | |

| 1820 | 638,829 | 14.8% | |

| 1830 | 737,987 | 15.5% | |

| 1840 | 753,419 | 2.1% | |

| 1850 | 869,039 | 15.3% | |

| 1860 | 992,622 | 14.2% | |

| 1870 | 1,071,361 | 7.9% | |

| 1880 | 1,399,750 | 30.7% | |

| 1890 | 1,617,949 | 15.6% | |

| 1900 | 1,893,810 | 17.1% | |

| 1910 | 2,206,287 | 16.5% | |

| 1920 | 2,559,123 | 16.0% | |

| 1930 | 3,170,276 | 23.9% | |

| 1940 | 3,571,623 | 12.7% | |

| 1950 | 4,061,929 | 13.7% | |

| 1960 | 4,556,155 | 12.2% | |

| 1970 | 5,082,059 | 11.5% | |

| 1980 | 5,881,766 | 15.7% | |

| 1990 | 6,628,637 | 12.7% | |

| 2000 | 8,049,313 | 21.4% | |

| Est. 2007 | 9,061,032 | 12.6% | |

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, as of 2006, North Carolina has an estimated population of 8,856,505, which is an increase of 184,046, or 2.1%, from the prior year and an increase of 810,014, or 10.0%, since the year 2000.[22] This exceeds the rate of growth for the United States as a whole. Between 2005 and 2006, North Carolina passed New Jersey to become the 10th most populous state.[23]

Racial Makeup and Population Trends

In 2007, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated that the racial makeup of North Carolina was as follows: 70 percent white American, 25.3 percent African American, 1.2 percent American Indian, and the remaining 6.5 percent are Hispanic. North Carolina has historically been a rural state, with most of the population living on farms or in small towns. However, over the last 30 years the state has undergone rapid urbanization, and today most of North Carolina's residents live in urban and suburban areas. In particular, the cities of Charlotte and Raleigh have become major urban centers, with large, diverse, mainly affluent, and rapidly growing populations. Most of this growth in diversity has been fueled by immigrants from Latin America, India, and Southeast Asia.[24]

| Ancestry | Percentage | Main article: |

|---|---|---|

| African | (21.6%) Of Total) | See African American |

| American | (13.9%) | See British American |

| English | (9.5%) | See English American |

| German | (9.5%) | See German American |

| Irish | (7.4%) | See Irish American |

| Scots-Irish | (3.2%) | See Scots-Irish American |

| Italian | (2.3%) | See Italian American |

| Scottish | (2.2%) | See Scottish American |

| County | Seat | 2010 Projection[25] |

|---|---|---|

| Mecklenburg | Charlotte | 925,084 |

| Wake | Raleigh | 900,072 |

| Guilford | Greensboro | 474,605 |

| Forsyth | Winston-Salem | 350,784 |

| Cumberland | Fayetteville | 311,777 |

| Durham | Durham | 262,256 |

| Buncombe | Asheville | 234,697 |

| Gaston | Gastonia | 205,489 |

| Union | Monroe | 203,527 |

| New Hanover | Wilmington | 200,401 |

African Americans

African Americans make up nearly a quarter of North Carolina's population. The number of middle-class blacks has increased since the 1970s. African Americans are concentrated in the state's eastern Coastal Plain and in parts of the Piedmont Plateau, where they had historically worked and where the most new job opportunities are.

Asian Americans

The state has a rapidly growing proportion of Asian Americans, specifically Indian and Vietnamese; these groups nearly quintupled and tripled, respectively, between 1990 and 2002, as people arrived in the state for new jobs in the growing economy. Recent estimates suggest that the state's Asian-American population has increased significantly since 2000. During the 1980s Hmong refugees from communist rule in Laos immigrated to North Carolina. They now number 12,000 in the state.[26]

European Americans

Settled first, the coastal region attracted primarily English immigrants of the early migrations, including indentured servants transported to the colonies and descendants of English who migrated from Virginia. In addition, there were waves of Protestant European immigration, including the British, Irish, French Huguenots,[27] and Swiss-Germans who settled New Bern. A concentration of Welsh (usually included with others from Britain and Ireland) settled east of present Fayetteville in the 18th century. For a long time the wealthier, educated planters of the coastal region dominated state government.

North Carolinians of Scots-Irish, Scottish and English ancestry are spread across the state. Historically Scots–Irish and Northern English settled mostly in the Piedmont and backcountry. They were the last and most numerous of the immigrant groups from the Britain and Ireland before the Revolution, and settled throughout the Appalachian South, where they could continue their own culture.[28] The Scots-Irish were fiercely independent and mostly yeoman farmers.

Hispanics

Since 1990 the state has seen an increase in the number of Hispanics/Latinos. Once chiefly employed as migrant labor, Hispanic residents of the 1990s and early 2000s have been attracted to low-skilled jobs in the state. As a result, growing numbers of Hispanic immigrants are settling in North Carolina, mainly from Mexico, Central America, and the Dominican Republic.

Native Americans

North Carolina has the highest American Indian population in the East Coast. The estimated population figures for Native Americans in North Carolina (as of 2004) is 110,198. To date, North Carolina recognizes eight Native American tribal nations within its state borders:[29], including the Eastern Band of Cherokees. Only five states: (California, Arizona, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Texas), have larger Native American populations than North Carolina.[30]

Religion

North Carolina, like other Southern states, has traditionally been overwhelmingly Protestant. By the late 19th century, the largest Protestant denomination was the Southern Baptists. However, the rapid influx of northerners and immigrants from Latin America is steadily increasing the number of Roman Catholics and Jews in the state. Yet, the numerical dominance of the Baptist Church remains strong.

Other information

State symbols

- State motto: Esse quam videri ("To be, rather than to seem") (1893)

- State song: "The Old North State" (1927)

- State flower: Dogwood (1941)

- State bird: Cardinal (1943)

- State colors: the red and blue of the N.C. and U.S. flags (1945)

- State toast: The Tar Heel Toast (1957)

- State tree: Pine (1963)

- State shell: Scotch bonnet (1965)

- State mammal: Eastern Grey Squirrel (1969)

- State salt water fish: Red Drum (also known as the Channel bass) (1971)

- State insect: European honey bee (1973)

- State gemstone: Emerald (1973)

- State reptile: Eastern Box Turtle (1979)

- State rock: Granite (1979)

- State beverage: Milk (1987)

- State historical boat: Shad boat (1987)

- State language: English (1987)

- State dog: Plott Hound (1989)

- State military academy: Oak Ridge Military Academy (1991)

- State tartan: Carolina tartan (1991)[31]

- State vegetable: Sweet potato (1995)

- State red berry: Strawberry (2001)

- State blue berry: Blueberry (2001)

- State fruit: Scuppernong grape (2001)

- State wildflower: Carolina Lily (2003)

- State Christmas tree: Fraser Fir (2005)

- State carnivorous plant: Venus Flytrap (2005)

- State folk dance: Clogging (2005)

- State popular dance: Shag (2005)

- State freshwater trout: Southern Appalachian Brook Trout (2005)

- State birthplace of traditional pottery: the Seagrove area (2005)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedusgs - ↑ [http://antiquity.ac.uk/ProjGall/moore/index.html David G. Moore, Robin A. Beck, Jr., and Christopher B. Rodning, "Joara and Fort San Juan: culture contact at the edge of the world," Antiquity, Vol.78, No. 229, Mar 2004, accessed 26 Jun 2008

- ↑ Constance E. Richards, "Contact and Conflict" [1], American Archaeologist, Spring 2008, accessed 26 Jun 2008

- ↑ Randinelli, Tracey. Tanglewood Park. Orlando, Florida: Harcourt, 16. ISBN 0-15-333476-2.

- ↑ http://statelibrary.dcr.state.nc.us/NC/HISTORY/HISTORY.HTM North Carolina State Library - North Carolina History

- ↑ Fenn and Wood, Natives and Newcomers, pp. 24-25

- ↑ Powell, North Carolina Through Four Centuries, p. 105

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Lefler and Newsome, (1973)

- ↑ Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans in Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware, Accessed 15 Feb 2008

- ↑ The Great Seal of North Carolina. NETSTATE. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ↑ John Hope Franklin, Free Negroes of North Carolina, 1789-1860, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1941, reprint, 1991

- ↑ NC Business History

- ↑ Historical Census Browser, 1860 US Census, University of Virginia, accessed 21 Mar 2008

- ↑ Gross State Product. U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (2006-06-23). Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ↑ Per Capita Personal Income. U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (September 2006). Retrieved 2006-10-23.

- ↑ Fishman, China, Inc.: How the Rise of the Next Superpower Challenges America and the World, p. 179

- ↑ http://www.soc.duke.edu/NC_GlobalEconomy/textiles/overview.php

- ↑ NC Department of Commerce Wine and Grape Industry web site.

- ↑ (April 29, 2007) Time for tobacco burning out in N.C.. Associated Press.

- ↑ North Carolina Research Campus. Retrieved 2006-12-17.

- ↑ North Carolina State Legislature. (NC § 90‑94) / (NC § 90‑95 subs 4).

- ↑ North Carolina QuickFacts.

- ↑ Table 1: Estimates of Population Change for the United States and States, and for Puerto Rico and State Rankings: July 1, 2005 to July 1, 2006. United States Census Bureau. December 22, 2006. Last accessed December 22, 2006.

- ↑ Contemporary Migration in North Carolina.

- ↑ County Population Growth 2010 - 2020. North Carolina State Demographics. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ↑ See a report on immigration by The Center for New North Carolinians of the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, entitled Ethnic Groups in North Carolina. Retrieved July 29, 2007.

- ↑ North Carolina-Colonization-The Southern Colonies

- ↑ David Hackett Fischer, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America, New York: Oxford University Press, 1989, pp.632-639

- ↑ Tribes and Organizations. North Carolina Department of Administration. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ↑ State Rankings—Statistical Abstract of the United States. U.S. Census Bureau (2004-07). Retrieved 2006-12-17.

- ↑ Secretary of State of North Carolina.

Resources

- William S. Powell and Jay Mazzocchi, eds. Encyclopedia of North Carolina (2006) 1320pp; 2000 articles by 550 experts on all topics; ISBN 0-8078-3071-2

- James Clay and Douglas Orr, eds., North Carolina Atlas: Portrait of a Changing Southern State (University of North Carolina Press, 1971).

- Crow; Jeffrey J. and Larry E. Tise; Writing North Carolina History University of North Carolina Press, (1979) online

- Fleer; Jack D. North Carolina Government & Politics University of Nebraska Press, (1994) online political science textbook

- Marianne M. Kersey and Ran Coble, eds., North Carolina Focus: An Anthology on State Government, Politics, and Policy, 2d ed., (Raleigh: North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research, 1989).

- Lefler; Hugh Talmage. A Guide to the Study and Reading of North Carolina History University of North Carolina Press, (1963) online

- Hugh Talmage Lefler and Albert Ray Newsome, North Carolina: The History of a Southern State University of North Carolina Press (1954, 1963, 1973), college textbook

- Paul Luebke, Tar Heel Politics: Myths and Realities (University of North Carolina Press, 1990).

- William S. Powell, North Carolina through Four Centuries University of North Carolina Press (1989), college textbook.

Primary sources

- Hugh Lefler, North Carolina History Told by Contemporaries (University of North Carolina Press, numerous editions since 1934)

- H. G. Jones, North Carolina Illustrated, 1524-1984 (University of North Carolina Press, 1984)

- North Carolina Manual, published biennially by the Department of the Secretary of State since 1941.

External links

Government and education

- Currituck County, NC

- North Carolina state government

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park

- North Carolina State Databases - Annotated list of searchable databases produced by North Carolina state agencies and compiled by the Government Documents Roundtable of the American Library Association.

- North Carolina Department of Commerce

- North Carolina state library

- Energy & Environmental Data for North Carolina

- USGS real-time, geographic, and other scientific resources of North Carolina

- North Carolina facts from US Department of Agriculture ERS

- North Carolina Court System official site

- North Carolina facts from US Census Bureau

- North Carolina Travel and Tourism Website

- NC ECHO - North Carolina Exploring Cultural Heritage Online

- North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- Green 'N' Growing: The History of Home Demonstration and 4-H Youth Development in North Carolina - hosted by NCSU Libraries Special Collections Research Center

- NC Office of Archives and History

- NC Museum of History

Other links

- Old Growth Forest Wilderness Areas in Western North Carolina

- Old Growth Forest Wilderness Areas in Eastern North Carolina

- The Appalachian Trail

- Updates of statewide trends since publication of The North Carolina Atlas in 2000

- North Carolina Information

- Lost Colony Blog

- Interactive North Carolina for Kids

- Sketches of North Carolina by William Henry Foote (1846) - Full-text history book

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.