|

|

| (24 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | {{Claimed}}{{Started}} | + | {{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} |

| | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] |

| | [[Category:Law]] | | [[Category:Law]] |

| | | | |

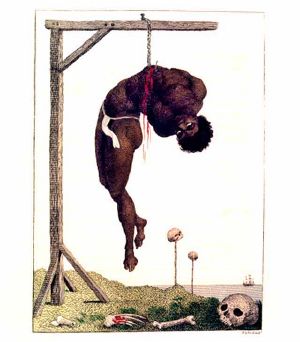

| | + | [[Image:BLAKE12.JPG|thumb|"A Negro Hung Alive by the Ribs to a Gallows" by [[William Blake]].]] |

| | + | '''Lynching''' is a form of violence, usually [[murder]], considered by its perpetrators as extra-legal [[punishment]] for offenders, or as a [[terrorism|terrorist]] method of enforcing social domination. It is characterized by a summary procedure ignoring, or even contrary to, the strict forms of [[law]]. Lynching is sometimes justified by its supporters as the administration of justice (in a social-moral sense, not in law) without the delays and inefficiencies inherent to the legal system. Victims of lynching have generally been members of groups marginalized or vilified by society. The practice is age-old; stoning, for example, is believed to have started long before [[lapidation]] was adopted as a judicial form of execution. "Lynch law" is frequently prevalent in sparsely settled or frontier districts, where government is weak and officers of the law too few and too powerless to preserve order. The practice has been common in periods of threatened [[anarchy]]. In the early twentieth century, it was also found significantly in [[Russia]] and south-eastern [[Europe]], but especially and almost peculiarly in [[United States|America]]. When the debate over [[capital punishment]] itself has reached the level that many countries have abolished the death penalty even through the judicial process, the idea of lynching alleged offenders without any regard for their [[human rights]] can be understood as very wrong, and part of the dark history of humankind. |

| | + | {{toc}} |

| | + | == Etymology == |

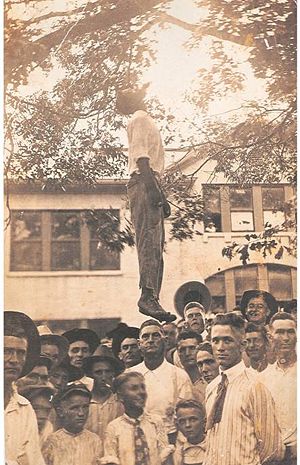

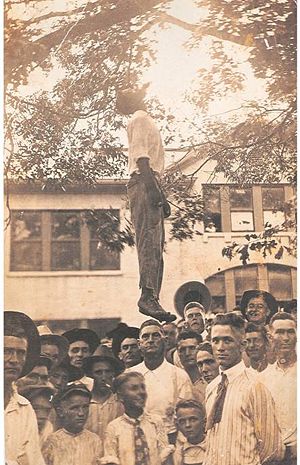

| | + | [[Image:Lynching-of-lige-daniels.jpg|right|thumb|300px|Postcard depicting the lynching of Lige Daniels, Center, [[Texas]], [[United States|USA]], August 3, 1920. The back reads, "This was made in the court yard in Center, Texas. He is a 16 year old Black boy. He killed Earl's grandma. She was Florence's mother. Give this to Bud. From Aunt Myrtle."]] |

| | + | The word '''lynching''' is recorded in [[English language|English]] since 1835, as a verb derived from the earlier expression "Lynch law" (known since 1811). This phrase is likely named after the Lynch family name. |

| | | | |

| − | '''Lynching''' is a form of violence, usually [[murder]], conceived of by its perpetrators as extra-legal punishment for offenders or as a [[terrorism|terrorist]] method of enforcing social domination. It is characterized by a summary procedure ignoring, or even contrary to, the strict forms of law, notably judicial [[execution (legal)|execution]]. Victims of lynching have generally been members of groups marginalized or vilified by society. The practice is age-old; stoning, for example, is believed to have started long before [[lapidation]] was adopted as a judicial form of execution.

| + | The most likely eponym for the concept of Lynch law as summary justice is [[William Lynch]], the author of "Lynch's Law." This was an agreement with the [[Virginia General Assembly]] (Virginian state legislature) on September 22, 1782, which allowed Lynch to pursue and punish criminals in Pittsylvania County, without due process of law, because legal proceedings were in practical terms impossible in the area due to the lack of adequate provision of courts. |

| − | | |

| − | "Lynch law" is frequently prevalent in sparsely settled or frontier districts, where government is weak and officers of the law too few and too powerless to preserve order. The practice has been common in periods of threatened [[anarchy]]. In the early twentieth century it was also found significantly in Russia and south-eastern Europe, but especially and almost peculiarly in America.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Lynching is sometimes justified by its supporters as the administration of justice (in a social-moral sense, not in law) without the delays and inefficiencies inherent to the legal system; in this way it echoes the [[Reign of Terror]] during the [[French Revolution]], which was justified by the claim, "Terror is nothing other than prompt, severe, inflexible justice."<ref>La terreur n'est autre chose que la justice prompte, sévère, inflexible. — [[Maximilien Robespierre]], address to the [[National Convention]], 17 pluviôse an II (5 February 1794)</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | == Etymology ==

| |

| − | The word "lynching" is recorded in English since 1835, as a verb derived from the earlier expression ''Lynch law'' (known since 1811). This phrase is likely named after the Lynch family (see below), whose surname derives either from Old English ''hlinc'' "hill" or from Irish ''Loingseach'' "sailor," though which member remains disputed.

| |

| − | [[Image:Lynching-of-lige-daniels.jpg|left|thumb|300px|Postcard depicting the lynching of Lige Daniels, [[Center, Texas|Center]], [[Texas]], USA, August 3, 1920. The back reads, "This was made in the court yard in Center, Texas. He is a 16 year old Black boy. He killed Earl's grandma. She was Florence's mother. Give this to Bud. From Aunt Myrtle."]]

| |

| | | | |

| − | The most likely [[eponym]] for the concept of Lynch law as summary justice is [[William Lynch]], the author of "Lynch's Law," an agreement with the [[Virginia General Assembly]] (Virginian state legislature) on September 22, 1782, which allowed Lynch to pursue and punish criminals in [[Pittsylvania County]], without due process of law, because legal proceedings were in practical terms impossible in the area due to the lack of adequate provision of courts.

| + | Others believe the term came into use only with Colonel [[Charles Lynch]], a Virginia magistrate and officer on the revolutionary side during the [[American Revolutionary War]]. He continued William's practice as the head of a vigilance committee, an irregular court trying and sentencing (in the form of fines and imprisonment) petty [[crime|criminals]] and pro-British Tories in his district circa 1782. |

| | | | |

| − | Others believe the term came into use only with [[Colonel]] [[Charles Lynch]], a Virginia magistrate and officer on the revolutionary side during the [[American Revolutionary War]], who in any case continued William's practice, as the head of a [[vigilance committee]], an irregular court, trying and sentencing to fining and imprisoning petty criminals and [[Loyalist (American Revolution)|pro- British 'Tories']] in his district circa 1782.

| + | In these cases only minor [[punishment]]s were used, mostly [[corporal punishment]], especially [[flogging]]. Neither William Lynch nor Charles Lynch ever [[execution|executed]] anyone. |

| − |

| |

| − | In these cases only minor punishments were used, mostly [[corporal punishment]], especially [[flogging]]. Neither William Lynch nor Charles Lynch ever executed anyone.

| |

| | | | |

| − | Extralegal punishments similar to those adopted by both Lynches continued to be duplicated by others in the newly independent [[United States|U.S.A.]] and elsewhere. The term "lynch law" came in to general use as a loosely employed description of efforts to maintain the established order either by the use of actual lynchings against those who would change it, or even their mere threat, which often proved sufficient to silence activists and critics. The term ''Lynch [[Crowd|mob]]'' — for a group of private persons who collectively practice lynching — is attested from 1838. | + | Extralegal punishments similar to those adopted by both Lynches continued to be duplicated by others in the newly independent [[United States|U.S.]] and elsewhere. The term "lynch law" came in to general use as a loosely employed description of efforts to maintain the established order either by the use of actual lynchings against those who would change it, or even their mere threat, which often proved sufficient to silence activists and critics. The term "Lynch mob"—for a group of private persons who collectively practice lynching—is attested from 1838. Since the Reconstruction Period after the Secession in the United States, the term came to mean, generally, the summary infliction of capital punishment. The further narrowing of the meaning to extralegal execution, specifically by [[hanging]], is from the twentieth century. |

| − | Since the Reconstruction Period after the Secession in the United States, it came to mean, generally, the summary infliction of capital punishment. The further narrowing of the meaning to extralegal execution specifically by hanging, is from the 20th century. | |

| | | | |

| − | === Alternative theories ===

| + | An alternative theory of origin arises from a text called the ''William Lynch Speech,'' alleged to have been written in 1712, and attributed to one "William Lynch," a [[Caribbean Sea|Caribbean]] planter and [[slavery|slave]] owner. This speech describes a plan to "break" and control slaves using intimidation and other methods. Though the speech is regarded by some historians as a fake, it has been cited numerous times by [[Louis Farrakhan]] and many others. |

| − | An alternative theory of origin arises from a text called the [[William Lynch Speech]], alleged to have been written in 1712, and attributed to one "William Lynch," a Caribbean planter and slave owner. This speech describes a plan to "break" and control slaves using intimidation and other methods. Though the speech is regarded by some historians as a fake, it has been cited numerous times by [[Louis Farrakhan]] and many others. | |

| | | | |

| − | Another suggestion is that it came from [[Lynchs Creek, South Carolina]], where summary justice was also administered to outlaws; some writers even attempted to trace it to Ireland, or to England. One unlikely theory traces it back to 1493 when James Fitzstephens Lynch, mayor and warden of [[Galway]] (Ireland), tried and executed his own son, but that would leave a transatlantic, centuries wide gap.{{cn}} | + | Another suggestion is that it came from Lynchs Creek, [[South Carolina]], where summary justice was also administered to outlaws; some writers even attempted to trace it to [[Ireland]], or to [[England]]. One unlikely theory traces it back to 1493 when James Fitzstephens Lynch, mayor and warden of [[Galway]] (Ireland), tried and executed his own son, but that would leave a transatlantic, centuries wide gap. |

| | | | |

| | + | == Social characteristics == |

| | + | [[Image:Lynching-of-will-james.jpg|left|thumb|330px|The circus-style lynching of Will James, Cairo, Illinois, 1909.]] |

| | + | There are generally two motives for lynchings. The first is the social aspect: Righting some social wrong or perceived social wrong (such as a violation of [[Jim Crow laws|Jim Crow]] etiquette). The second is the economic aspect. For example, upon successfully lynching a black farmer or immigrant merchant, the land would be available and the market opened for white Americans. The terror and intimidation produced by lynching can effectively serve as weapons in economic warfare. This motive was particularly prevalent in the post-[[American Civil War|Civil War]] South in America. Because many supporters of the Confederacy were barred from holding public positions of power, they sought to assert themselves through this economic warfare, which took the form of lynching the newly empowered African-Americans. A black [[journalism|journalist]], [[Ida B. Wells]], discovered in the 1890s that black lynch victims were accused of [[rape]] or attempted rape only about one-third of the time. The most prevalent accusation was [[murder]] or attempted murder, followed by a list of infractions that included verbal and physical [[aggression]], spirited [[business]] [[competition]], and independence of mind. After accusing these people of [[crime]]s, the communities then felt justified in lynching them for a supposed public good.<ref>Nell Irvin Painter, Who Was Lynched.</ref> |

| | | | |

| | + | Many lynchings are carried out with the participation of [[law enforcement]] and government officials. Police might detain a lynching target, then release him into a situation where a lynch mob could easily, and quietly, complete their deed.<ref>Greens.org, [http://www.greens.org/s-r/26/26-04.html Contemporary Police Brutality and Misconduct]. Retrieved April 12, 2007.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | == United States == | + | ==Historical examples== |

| − | | + | === United States === |

| − | Lynch Law—a form of mob violence and putative justice, usually involving (but by no means restricted to) the illegal hanging of suspected criminals—cast its pall over the [[Southern United States]] from the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries. Before the [[American Civil War|Civil War]], its victims were usually black slaves and persons suspected of aiding escaped [[slavery in the United States|slaves]]; lynching was mainly a frontier phenomenon. During [[Reconstruction]], the [[Ku Klux Klan]] and others used lynching as a means to curb what they viewed as excesses within the [[Radical Republican]] Reconstruction government. Federal troops operating under the [[Civil Rights Act of 1871]] largely broke up the Reconstruction-era Klan, and with the end of Reconstruction in 1876, white southerners regained nearly exclusive control of the region's governments and courts. Lynchings declined, but were by no means brought to an end. In 1892, 161 African-Americans were lynched.

| |

| − | | |

| − | After the 1915 release of the movie ''[[The Birth of a Nation]],'' which glorified the Reconstruction-era Klan, the Klan re-formed and re-adopted lynching as a means to socially, economically, and politically terrorize and paralyze black populations, in support of a [[white supremacy|white supremacist]] status quo. Victims were usually black men, often accused of assaulting or raping whites. Lynch Law declined sharply after 1935, and there have been no reported incidents of this type since the late 1960s.

| |

| − | [[Image:BLAKE12.JPG|thumb|"A Negro Hung Alive by the Ribs to a Gallows" by [[William Blake]].]]

| |

| − | The murders of 4,743 people who were lynched in the United States between 1882 and 1968 were not often publicized. It is likely that many more unrecorded lynchings occurred in this period. Lynching statistics were kept only for the 86 years between 1882 and 1968, and were based primarily on newspaper accounts. Yet the socio-political impact of lynchings could be significant, as illustrated by the restoration in 1901 of capital punishment in the state of [[Colorado]] (which had abolished it only in 1897) as the result of a lynching outbreak in 1900.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Most lynchings were inspired by unsolved crime, [[racism]], and innuendo. 3,500 of its victims were African Americans. Lynchings took place in every state except four, but were concentrated in the Cotton Belt ([[Mississippi]], [[Georgia (U.S. state)|Georgia]], [[Alabama]], [[Texas]] and [[Louisiana]]). <ref>Dahleen Glanton, "Controversial exhibit on lynching opens in Atlanta" May 5, 2002, ''Chicago Tribune''. [http://web.archive.org/web/20050311100917/http://www.deltasigmatheta.com/archiv13.htm Reproduced online] on the site of deltasigmatheta.com, archived on the [[Internet Archive]] March 11, 2005.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Members of mobs that participated in these public murders often took photographs of what they had done, and those photographs, distributed on postcards, were collected by John Allen who has now published them online <ref>[http://withoutsanctuary.org/ Musarium: Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photograhy in America]. Accessed 6 November 2006.</ref>, and written words to accompany the shocking images.

| |

| − | | |

| − | '''Lynching in the United States''' has influenced and been influenced by the major social conflicts in the country, revolving around the [[American frontier]], [[Reconstruction]], and the [[Civil rights|civil rights movement]]. Originally, [[lynching]] meant any extra-judicial punishment, including [[tarring and feathering]] and [[exile|running out of town]], but during the 19th century in the [[United States]], it began to be used to refer specifically to [[murder]], usually by [[hanging]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | On the American frontier, where the power of the police and the army was tenuous, lynching was seen by some as a positive alternative to lawlessness. In the Reconstruction-era [[Southern United States|South]], lynching of blacks was used, especially by the first [[Ku Klux Klan]], as a tool for reversing the social changes brought on by Federal occupation. This type of racially motivated lynching continued in the [[Jim Crow law|Jim Crow era]] as a way of enforcing subservience and preventing economic competition, and into the twentieth century as a method of resisting the civil rights movement.

| |

| − | | |

| − | === Early history === | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | Originally, lynching meant any extra-judicial punishment, often flogging, including tarring and feathering and running out of town, but during the 19th century in the United States, it began to be used to refer specifically to [[execution]], especially by hanging.

| |

| − | | |

| − | There is much debate over the violent history of lynchings on the frontier, obscured by the mythology of the [[American Old West]]. Some historians{{Fact|date=February 2007}} have argued, for example, that the [[California]] mining camps were relatively peaceful places, while others{{Fact|date=February 2007}} point to contemporary accounts stating that "We scarce ever take up a paper from the mining districts but what the eye is pained and the heart made sick with accounts of robberies and brutal murders, committed, it would seem, with almost entire impunity."<ref name="daily-alta-california-quote">Daily Alta California, September 16, 1850, quoted in the New York Times, July 1, 2005, p. A18.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Compared to their mythologized version, real lynchings on the frontier did not focus as strongly on "rough and ready" crime prevention, and often shared many of the same racist and partisan political dimensions as lynchings in the South and [[Midwestern United States|Midwest]]. In unorganized territories or sparsely-settled states, security was often provided only by a [[United States Marshal Service|federal marshal]] who might, despite the appointment of deputies, be hours or even days away by horse. But many lynchings on the frontier were carried out against accused criminals who were already in custody, and frequently the goal of lynching was not so much to substitute for an absent legal system as to provide an alternative system that would favor a particular social class or racial group. One historian writes, "Contrary to the popular understanding, early territorial lynching did not flow from an absence or distance of law enforcement but rather from the social instability of early communities and their contest for property, status, and the definition of social order."<ref name="pfeifer-frontier-quote">Pfeifer, Michael J. ''Rough Justice: Lynching and American Society, 1874-1947'', Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| | + | Lynching in the [[United States]] has influenced and been influenced by the major social conflicts in the country, revolving around the [[American frontier]], [[Reconstruction]], and the [[African-American Civil Rights Movement|civil rights movement]]. Originally, [[lynching]] meant any extra-judicial punishment, including [[tarring and feathering]] and [[exile]], but during the nineteenth century in the United States, it began to be used to refer specifically to [[murder]], usually by [[hanging]]. |

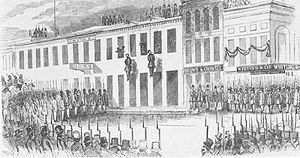

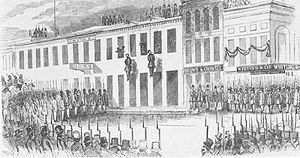

| | [[Image:lynching-of-casey-and-cora.jpg|left|300px|thumb|Charles Cora and James Casey are lynched by the Committee of Vigilance, San Francisco, 1856.]] | | [[Image:lynching-of-casey-and-cora.jpg|left|300px|thumb|Charles Cora and James Casey are lynched by the Committee of Vigilance, San Francisco, 1856.]] |

| − | The [[San Francisco Vigilance Movement]], for example, has traditionally been portrayed as a positive response to government corruption and rampant crime, but revisionists have argued that it created more lawlessness than it eliminated. It also had a strongly nativist tinge, initially focusing on the [[Irish American|Irish]] and later evolving into mob violence against [[Chinese American|Chinese]] immigrants. | + | The [[San Francisco Vigilance Movement]], for example, has traditionally been portrayed as a positive response to government corruption and rampant crime, but revisionists have argued that it created more lawlessness than it eliminated. It also had a strongly nativist tinge, initially focusing on the Irish and later evolving into mob violence against Chinese immigrants. |

| | | | |

| − | Another well documented episode in the history of the American West is the [[Johnson County War]], a dispute over land use in [[Wyoming]] in the 1890s. Large-scale ranchers, with the complicity of local and federal [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] politicians, hired mercenary soldiers and assassins to lynch the small ranchers (mostly [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democrats]]) who were their economic competitors and who they portrayed as "cattle rustlers."

| + | Lynch Law, a form of mob violence and putative justice, usually involving (but by no means restricted to) the illegal [[hanging]] of suspected criminals, cast its pall over the Southern United States from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries. Before the [[American Civil War|Civil War]], its victims were usually black [[slavery|slaves]] and persons suspected of aiding escaped slaves; lynching was mainly a frontier phenomenon. During [[Reconstruction]], the [[Ku Klux Klan]] and others used lynching as a means to curb what they viewed as excesses within the Radical Republican Reconstruction government. Federal troops operating under the [[Civil Rights Act of 1871]] largely broke up the Reconstruction-era Klan, and with the end of Reconstruction in 1876, white southerners regained nearly exclusive control of the region's governments and courts. Lynchings declined, but were by no means brought to an end. In 1892, 161 African-Americans were lynched. |

| | | | |

| − | Though not on the frontier, there were several lynchings in July 1863 as part of the [[New York Draft Riots]]. The riots were sparked in part by job competition between Irish-American immigrants and [[Freedmen|free blacks]], and during the riots 11 blacks were murdered, with many more beaten, and their property destroyed. The riots led to a brief exodus of blacks from New York and helped establish [[Harlem]] as the center of black society in the city.<ref name="draftriots">[http://www.press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/317749.html http://www.press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/317749.html], accessed February 20, 2007.</ref>

| + | On the American frontier, where the power of the [[police]] and the [[army]] was tenuous, lynching was seen by some as a positive alternative to lawlessness. In the Reconstruction-era [[Southern United States|South]], lynching of blacks was used, especially by the first Ku Klux Klan, as a tool for reversing the social changes brought on by Federal occupation. This type of racially motivated lynching continued in the [[Jim Crow laws|Jim Crow era]] as a way of enforcing subservience and preventing economic competition, and into the twentieth century as a method of resisting the civil rights movement. |

| | | | |

| − | === Reconstruction (1865-1877) ===

| |

| | [[Image:Kkk-carpetbagger-cartoon.jpg|right|200px|thumb|A cartoon threatening that the [[Ku Klux Klan|KKK]] would lynch [[carpetbagger]]s. Tuscaloosa, Alabama, ''Independent Monitor'', 1868.]] | | [[Image:Kkk-carpetbagger-cartoon.jpg|right|200px|thumb|A cartoon threatening that the [[Ku Klux Klan|KKK]] would lynch [[carpetbagger]]s. Tuscaloosa, Alabama, ''Independent Monitor'', 1868.]] |

| − | After the [[American Civil War|Civil War]], lynching became particularly associated with the South and with the first Ku Klux Klan, which was founded in 1866.

| + | In 1915, three closely related events occurred: The lynching of [[Leo Frank]], the release of the film ''The Birth of a Nation,'' and the reorganization of the Ku Klux Klan. |

| − | | + | [[Image:LeoFranknewspaper.jpg|left|thumb|Cover of the ''Atlanta Constitution'' with Leo Frank]] |

| − | The first heavy period of lynching in the South was between 1868 and 1871. It began with a purge of black and white Republicans by white Democrats. Whites had decided to prevent the ratification of new constitutions by preventing people from voting. Failed attempts at terrorization led to a massacre during the 1868 elections, with the systematic murder of about 1,300 voters across various southern states ranging from [[South Carolina]] to [[Arkansas]]. | + | The 1915 murder of factory manager Leo Frank, an American Jew, was one of the more notorious lynchings of a non-African-American. In sensationalist [[newspaper]] accounts, Frank was accused of fantastic sexual crimes, and of the murder of Mary Phagan, a girl employed by his factory. He was convicted of murder after a questionable trial in Georgia (the judge asked that Frank and his counsel not be present when the verdict was announced because of the violent mob of people in the court house). His appeals failed and the governor then commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, but a mob calling itself the Knights of Mary Phagan kidnapped Frank from the prison farm, and lynched him. |

| − | | |

| − | After this partisan political violence had ended, lynchings in the South focused more on race than on partisan politics, and can be seen as a latter-day expression of the [[slave patrol]]s, the bands of poor whites who policed the slaves and pursued escapees. The lynchers sometimes murdered their victims but sometimes whipped them to remind them of their former status as slaves.<ref name="whipping">Dray, Philip. ''At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America'', New York: Random House, 2002</ref> White vigilantes often made nighttime raids of black homes in order to confiscate their firearms. Lynchings aimed at preventing freedmen from voting and bearing arms can be seen as extralegal ways of enforcing the [[Black Codes]], which were largely invalidated by the [[Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution|14th]] and [[Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution|15th]] Amendments in 1868 and 1870 and were followed by the Jim Crow laws.

| |

| − | | |

| − | After years of terror, President [[Ulysses S. Grant]] and [[United States Congress|Congress]] passed the [[Civil Rights Act of 1871]]. This permitted authorities to use [[martial law]] in some counties in South Carolina, where the Klan was the strongest. At about this time, the Klan dissipated. Vigorous federal action and the disappearance of the Klan had a strong effect in reducing lynching. From 1868 to 1876, most years had 50-100 lynchings, but from 1877 to 1888, the toll ranged from 1 to 17 victims per year.

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Image:lynching-1889.jpg|right|thumb|170px|Lynching victim, 1889]] | |

| − | | |

| − | ===1877 to World War II===

| |

| − | While the vast majority of lynchings were of blacks, during the 1800s and early 20th century, [[Italian-Americans]] were the second most common target of lynchings. On March 14, 1891, eleven Italian-Americans were lynched in [[New Orleans]] after a jury found them not guilty in the case of the murder of a New Orleans police chief [http://www.odmp.org/officer.php?oid=6389] [[David Hennessy]]. The eleven were falsely accused of being associated with the [[Mafia]]. This incident was the largest mass lynching in U.S. history. Lynchings of Italian-Americans occurred mostly in the South but also occurred in New York, [[Pennsylvania]], and [[Colorado]]. Chinese immigrants, East [[India]]ns, and [[Native Americans in the United States|Native Americans]] were also likely lynching victims.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==== Enforcing Jim Crow ====

| |

| − | After 1876, the frequency of lynching decreased, and it became a threat used to terrorize blacks and maintain the new, racist social order that was being constructed. Congress had housed many southern Republicans who sought to protect black voting rights by using federal troops. A congressional deal to elect [[Rutherford B. Hayes]] as President in 1876 included a pledge to end Reconstruction in the South. The [[Redeemers]], white racists who often included [[White Cappers]] and Ku Klux Klan members, began to break any political power that blacks had gained during Reconstruction. Lynchings were seen as supporting the new status quo and were carried out in public.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Another reaction against Reconstruction was the creation of the Jim Crow laws beginning in the 1890s. Terror and lynching were used to enforce both these formal laws and a variety of [[Jim Crow etiquette|unwritten rules of conduct]] meant to assert white domination. From 1889 to 1923, most years had 50-100 lynchings.

| |

| − | | |

| | | | |

| − | Often Jim Crow tensions went hand in hand with economic tensions. In 1887, 10,000 workers at sugar plantations in Louisiana, organized by the [[Knights of Labor]], went on strike for an increase in their pay to $1.25 per day. Most of the workers were black, but some were white, infuriating Governor [[Samuel Douglas]], who declared that "God Almighty has himself drawn the color line." The militia was called in but then withdrawn to give free rein to a lynch mob in [[Thibodaux, Louisiana|Thibodaux]], which killed somewhere between 20 and 300 people. A black newspaper described the scene:<ref name="thibodaux-massacre">Zinn, 2004; [http://www.dougriddle.com/essays/sk20021220.html http://www.dougriddle.com/essays/sk20021220.html], accessed February 20, 2007.</ref>

| + | The recreation of the Klan was also greatly aided by D. W. Griffith's 1915 film ''The Birth of a Nation,'' which glorified the Klan. The film resonated strongly with many southerners who believed Frank was guilty, because they saw an analogy between Mary Phagan and the film's character Flora, a young [[virgin]] who throws herself off a cliff to avoid being raped by the black character Gus. After the release of the movie, the Klan re-formed with a new emphasis on violence against immigrants, [[Jewish American|Jews]], and [[Catholicism|Catholics]]. They used lynching as a means to socially, economically, and politically terrorize and paralyze these populations, in support of a [[white supremacy|white supremacist]] status quo. Lynch Law declined sharply after 1935, and there have been no reported incidents of this type since the late 1960s. |

| − | :"Six killed and five wounded" is that the daily papers here say, but from an eye witness to the whole transaction we learn that no less than thirty-five Negroes were killed outright. Lame men and blind women shot; children and hoary-headed grandsires ruthlessly swept down! The Negroes offered no resistance; the could not, as the killing was unexpected. Those of them not killed took to the woods, a majority of them finding refuge in this city.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Labor conflict was also behind the 1917 [[East St. Louis Riot]], where white workers' anger at African American competition for jobs was a primary cause of racial violence. While newspapers estimated the death toll as high as 200 blacks, the official estimate remains 39 blacks and 9 whites.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===New Klan===

| |

| − | In 1915, three closely related events occurred: the lynching of [[Leo Frank]], the release of the film ''[[The Birth of a Nation]]'', and the reorganization of the Ku Klux Klan with a new emphasis on violence against immigrants, [[Jewish American|Jews]], and [[Catholicism|Catholics]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Image:LeoFranknewspaper.jpg|right|thumb|Cover of the ''Atlanta Constitution'' with Leo Frank]]

| |

| − | The 1915 murder of factory manager Leo Frank, an American Jew, was one of the more notorious lynchings of a non-African-American. In sensationalistic newspaper accounts, Frank was accused of fantastic sexual crimes, and of the murder of a [[Mary Phagan]], a girl employed by his factory. He was convicted of murder after a questionable trial in Georgia (the judge asked that Frank and his counsel not be present when the verdict was announced because of the violent mob of people in the court house). His appeals failed (Supreme court justice [[Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.|Oliver Wendell Holmes]] dissented, condemning the intimidation of the jury as failing to provide due process of law). The governor then commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, but a mob calling itself the Knights of Mary Phagan kidnapped Frank from the prison farm, and lynched him. Ironically, the evidence in the murder actually pointed to the factory's black janitor, Jim Conley, who had a criminal record, was seen washing a bloody shirt, and repeatedly changed his story. It later came out that Conley had confessed to three different people that he had been Phagan's murderer. Many black Americans believed that the extensive national attention focused on Frank as an "American [[Dreyfus affair|Dreyfus]]"<ref name="whipping"/> would never have happened if Frank had been black.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | The Frank trial was used skillfully by Georgia politician and publisher [[Thomas E. Watson|Tom Watson]] as a strategy to build support for the reorganization of the Ku Klux Klan, with a new [[anti-Jewish]], [[anti-Catholic]], and [[nativism (politics)|nativist]] slant. The new Klan was inaugurated in 1915 at a [[Stone Mountain|mountaintop]] meeting attended by aging members of the original Klan, along with members of the Knights of Mary Phagan. The recreation of the Klan was also greatly aided by [[D. W. Griffith]]'s 1915 film ''The Birth of a Nation'', which glorified the Klan. The film resonated strongly with many southerners who believed Frank was guilty, because they saw an analogy between Mary Phagan and the film's character Flora, a young virgin who throws herself off a cliff to avoid being raped by the black character Gus, described as "a renegade, a product of the vicious doctrines spread by the [[carpetbagger]]s."

| |

| | | | |

| | + | The murders of 4,743 people who were lynched in the United States between 1882 and 1968 were not often publicized. It is likely that many more unrecorded lynchings occurred in this period. Lynching [[statistics]] were kept only for the 86 years between 1882 and 1968, and were based primarily on newspaper accounts. Yet the socio-political impact of lynchings could be significant, as illustrated by the restoration in 1901 of [[capital punishment]] in the state of [[Colorado]] (which had abolished it only in 1897) as the result of a lynching outbreak in 1900. |

| | [[Image:Lynching-of-jesse-washington.jpg|left|thumb|300px|right|A postcard showing the burned body of Jesse Washington, [[Waco, Texas]], 1916. Washington, a 17-year-old mentally handicapped farmhand who had confessed to raping and killing a white woman, was castrated, mutilated, and burned alive by a cheering mob including mayor and the chief of police. An observer wrote that "Washington was beaten with shovels and bricks... [he] was castrated, and his ears were cut off. A tree supported the iron chain that lifted him above the fire... Wailing, the boy attempted to climb up the skillet hot chain. For this, the men cut off his fingers." This image is from a postcard, which said on the back, "This is the barbeque we had last night. My picture is to the left with a cross over it. Your son, Joe."]] | | [[Image:Lynching-of-jesse-washington.jpg|left|thumb|300px|right|A postcard showing the burned body of Jesse Washington, [[Waco, Texas]], 1916. Washington, a 17-year-old mentally handicapped farmhand who had confessed to raping and killing a white woman, was castrated, mutilated, and burned alive by a cheering mob including mayor and the chief of police. An observer wrote that "Washington was beaten with shovels and bricks... [he] was castrated, and his ears were cut off. A tree supported the iron chain that lifted him above the fire... Wailing, the boy attempted to climb up the skillet hot chain. For this, the men cut off his fingers." This image is from a postcard, which said on the back, "This is the barbeque we had last night. My picture is to the left with a cross over it. Your son, Joe."]] |

| | + | |

| | + | Most lynchings were inspired by unsolved [[crime]], [[racism]], and innuendo. 3,500 of its victims were African Americans. Lynchings took place in every state except four, but were concentrated in the Cotton Belt ([[Mississippi]], [[Georgia (U.S. state)|Georgia]], [[Alabama]], [[Texas]] and [[Louisiana]]).<ref>Dahleen Glanton, "Controversial exhibit on lynching opens in Atlanta" May 5, 2002, ''Chicago Tribune''. [http://web.archive.org/web/20050311100917/http://www.deltasigmatheta.com/archiv13.htm Reproduced online] on the site of deltasigmatheta.com, archived on the Internet Archive March 11, 2005.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | === Social characteristics ===

| + | Members of mobs that participated in these public murders often took photographs of what they had done, and those photographs, distributed on postcards, were collected by John Allen who has now published them online <ref>Without Sanctuary, [http://withoutsanctuary.org/ Lynching Photography in America]. Retrieved July 3, 2007.</ref>, and written words to accompany the shocking images. |

| − | There were often two motives for lynchings in the United States. The first was the social aspect: righting some social wrong or perceived social wrong (such as a violation of Jim Crow etiquette). The second was the economic aspect. For example, upon successful lynching of a black farmer or immigrant merchant, the land would be available and the market opened for white Americans. A black journalist, [[#Anti-lynching movement|Ida B. Wells]], discovered in the 1890s that black lynch victims were accused of rape or attempted rape only about one-third of the time. The most prevalent accusation was murder or attempted murder, followed by a list of infractions that included verbal and physical aggression, spirited business competition and independence of mind.<ref name="whowaslynched">http://www.nellpainter.com/nell/cv/articles/32_WhoWasLynched.html</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Lynch mobs enforced the racist social order through beatings, cutting off fingers, burning down houses, and/or destroying the crops of African-Americans. Murder was a common form of lynch mob "justice," sometimes with the complicity of law-enforcement authorities who participated directly or held victims in jail until a mob formed to carry out the murder. Most lynchings terminated with a hanging, but victims were sometimes tortured prior to being killed by such methods as beating, burning, stabbing, sexual mutilation and eye-gouging. Photographs of these events frequently show the perpetrators laughing and smiling. Next to hanging, the most common methods of killing were burning alive, shooting, and beating to death.

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Image:Lynching-of-will-james.jpg|left|thumb|330px|The circus-style lynching of Will James, [[Cairo, Illinois]], 1909.]]

| |

| | | | |

| − | Often victims were lynched by a small group of white vigilantes late at night. Sometimes, however, lynchings became mass spectacles with a circus atmosphere. Children often attended these public lynchings, which anti-lynching advocates saw as a form of indoctrination. A large lynching might be announced beforehand in the newspaper, and there were cases in which a lynching was started early so that a newspaper reporter could make his deadline. It was common for postcards to be sold depicting lynchings, typically allowing a newspaper photographer to make some extra money. These postcards became popular enough to be an embarrassment to the government, and the postmaster officially banned them in 1908. However, the lynching postcards continued to exist through the 1930s.

| + | === Mexico === |

| | + | On November 23, 2004, in the Tlahuac lynching, three [[Mexico|Mexican]] undercover federal agents doing a [[narcotics]] investigation were lynched in the town of San Juan Ixtayopan ([[Mexico City]]) by an angry crowd who saw them taking [[photograph]]s and mistakenly suspected they were trying to abduct children from a [[primary school]]. The agents identified themselves immediately but were held and beaten for several hours before two of them were killed and set on fire. The whole incident was covered by the [[mass media|media]] almost from the beginning, including their pleas for help and their [[murder]]. |

| | | | |

| − | Many lynchings were carried out with participation by law enforcement and government officials. Police might detain a lynching target, then release him into a situation where a lynch mob could easily, and quietly, complete their deed. Fewer than 1% of lynch mob participants were ever convicted. Trial juries in the southeastern United States were typically all-white and would not vote to convict lynchers, and often coroner's juries never let the matter go past the inquest. In a typical 1892 example in [[Port Jervis, New York]], a police officer tried to stop the lynching of a black man who, it was revealed after his death, had been wrongfully accused of assaulting a white woman. The mob responded by putting the noose around the officer's neck as a way of scaring him off. At the coroner's inquest, the officer identified eight people who had participated in the lynching, including the former chief of police, but the coroner's jury found that the murder had been carried out "by person or persons unknown."<ref name="port-jervis">Pfeifer, 2004, p. 35.</ref>

| + | By the time police rescue units arrived, two of the agents were reduced to charred corpses and the third was seriously injured. Authorities suspect the lynching was provoked by the persons being investigated. |

| | | | |

| − | [[Image:duluth-lynching-postcard.jpg|left|thumb|300px|Postcard of the Duluth lynching.]] | + | Both local and federal authorities abandoned them to their fate, saying the town was too far away to even try to arrive in time and some officials stating they would provoke a massacre if they tried to rescue them from the mob.<ref>ABC News Online, [http://www.abc.net.au/news/newsitems/200411/s1253184.htm Mexican Police Chiefs Fired Over Agents' Lynching.] Retrieved March 29, 2007.</ref> |

| − | More than 85% of the estimated 5,000 lynchings in the post-Civil War period occurred in the southern states, but the problem was nationwide, peaking in 1892 when 161 African-Americans were lynched.

| |

| | | | |

| − | Not all racially motivated lynchings in the United States took place in the South. One such incident occurred in [[Duluth, Minnesota]], on June 15, 1920, when three young African-American travelers were dragged from their jail cells (where they were confined after being accused of raping a white woman) and lynched by a mob believed to number more than one thousand. The [[Duluth lynchings]] event became the subject of a non-fiction book, ''The Lynchings in Duluth''.

| + | === Europe === |

| | + | [[Image:Prina lynched.jpg|thumb|left|250 px|The murder of Giuseppe Prina at the hands of a mob]] |

| | + | In [[Europe]], early examples of a similar phenomenon are found in the proceedings of the ''Vehmgerichte'' in medieval [[Germany]], and of [[Lydford law]], [[gibbet law]] or [[Halifax law]], [[Cowper justice]], and [[Jeddart justice]] in the thinly settled and border districts of [[Great Britain]]. |

| | + | Count Giuseppe Prina, an [[Italy|Italian]] statesman, was killed in the [[Milan]] [[riot]]s of 1814. A furious mob burst into the [[senate]], pillaged its halls and searched for Prina. Not finding him there, the rioters rushed to his house, which they wrecked, and seized the doomed minister, who was discovered in a remote chamber donning a disguise. Over the course of four hours, the angry rioters dragged him about the town, until wounded, mutilated, and almost torn to pieces, Prina received his death-blow. |

| | | | |

| − | Since lynchings were often carried out on the pretext of protecting white women (from rape by black men), in 1930, white women formed the [[Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching]] to repudiate the claim that this was the true purpose of lynching.<ref name="southernwomen">http://lists.econ.utah.edu/pipermail/margins-to-centre/2005-February/000201.html</ref> Further doubt was cast on this claim in 1965, when [[Viola Liuzzo]], a white mother of five who had been raised in the South, was murdered by Ku Klux Klan members after she participated in the civil rights march from [[Selma, Alabama|Selma]] to [[Montgomery, Alabama|Montgomery]].

| + | In 1944, [[Wolfgang Rosterg]], a German [[prisoner of war|POW]] known to be unsympathetic to the [[Nazism|Nazi]] regime in Germany, was lynched by Nazi fanatics in prisoner of war Camp 21 in [[Comrie]], [[Scotland]]. After the end of the [[World War II|war]], five of the perpetrators were [[hanging|hanged]] at Pentonville Prison—the largest multiple execution in twentieth century Britain.<ref>Caledonia TV, [http://www.caledonia.tv/index.php?page=16 Execution at Camp 21.] Retrieved April 17, 2007.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | Rather than seeing racial lynching in the post-Civil War South as unique, social historian [[Michael J. Pfeifer]] emphasizes the continuity of lynching with other forms of legal and extralegal violence, such as [[duel|dueling]], the [[War of the Regulation|Regulator Movement]], and even [[capital punishment]]: "Eventually the rural and working class 'rough justice' enthusiasts who endorsed mob murder in the Midwest, West, and South compromised with the bourgeois advocates of due process law. In the early 20th century, states in those regions, aping the punitive innovations of northeastern states, revamped the death penalty into a comparatively efficient, technocratic, and highly racialized mechanism of retributive justice, and lynchings ceased."<ref name="capital-punishment">[http://academic.evergreen.edu/p/pfeiferm/home.htm http://academic.evergreen.edu/p/pfeiferm/home.htm], accessed February 20, 2007.</ref> In this view, America had two legal systems running in parallel, a formal one in the courts and an informal one that operated via lynching, but both were highly racially polarized, and both operated to enforce white social dominance. In the opinion of Senator [[Mary Landrieu]], however, "Lynching was a form of [[terrorism]] practiced by Americans against other Americans."<ref name="landrieu-terrorism">USA Today, June 13, 2005, [http://fullcoverage.yahoo.com/s/usatoday/senatemovestoapologizeforinjustice http://fullcoverage.yahoo.com/s/usatoday/senatemovestoapologizeforinjustice], retrieved June 28, 2005.</ref> Neither explanation fits the facts in every case. Terrorism is a more natural explanation of the highly political violence of the 1868 massacres, as well as the bulk of the Ku Klux Klan's actions, and especially examples such as the random lynching of [[Michael Donald]], or a 1981 Klan action at a marina in [[Galveston]], in which robed and armed klansmen frightened [[Vietnam]]ese shrimp fishermen by sailing a boat up and down, with a dummy hanging by its neck in the rigging.<ref name="shrimp">Stanton, Bill. ''Klanwatch: Bringing the Ku Klux Klan to Justice'', New York: Grove, 1991</ref> On the other hand, Pfeifer's hypothesis that lynchings expressed a desire for personalized, retributive justice is supported by examples such as the circus-style lynching of [[Jesse Washington]], a retarded man who had already confessed to murder and rape.

| + | There are also some personal accounts of lynching in [[Budapest]], [[Hungary]] during the [[1956 Hungarian Revolution]] against the occupying [[Soviet Union|Soviets]]. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Resistance=== | + | ===Russia=== |

| | + | A number of anti-Jewish riots known as [[pogrom|pogroms]] swept [[Russia]] in the nineteenth century. They were sparked by the assassination of [[Tsar Alexander II]], for which alarmists blamed Russia's Jewish population. Local economic conditions are thought to have contributed significantly to the [[riot]]ing, especially with regard to the participation of the business competitors of local Jews and the participation of railroad workers, and it has been argued that this was actually more important than rumors of Jewish responsibility for the death of the Tsar.<ref>I. Michael Aronson, "Geographical and Socioeconomic Factors in the 1881 Anti-Jewish Pogroms in Russia," ''Russian Review'', Vol. 39, No. 1. (Jan., 1980), pp. 18-31</ref> These rumors, however, were clearly of importance, if only as a trigger, and had a small kernel of truth: One of the close associates of the assassins, [[Gesya Gelfman]], was indeed Jewish. The fact that the other assassins were all Christian had little impact. Although the pogroms claimed the lives of relatively few Jews (2 Jews were killed by the mobs, while 19 attackers were killed by tsarist authorities), the damage, disruption, and disturbance were dramatic. The pogroms and the official reaction to them led many Russian Jews to reassess their perceptions of their status within the Russian Empire, and so also led to significant Jewish [[emigration]], mostly to the [[United States]]. Changed perceptions among Russian Jews also indirectly gave a significant boost to the early [[Zionism|Zionist]] movement. |

| | | | |

| − | [[Image:Idawells.jpg|right|thumb|120px|Ida B. Wells-Barnett led a crusade against lynching.]]

| + | A much bloodier wave of pogroms broke out in 1903-1906, leaving an estimated 2,000 Jews dead, and many more wounded, as the Jews took to arms to defend their families and property from the attackers. The number of people of other nationalities killed or wounded in these pogroms exceeded Jewish casualties.<ref>Vadim Kozhinov, [http://www.hrono.ru/libris/kozhin20vek.html Russia XXth Century (1901-1939).] Retrieved July 3, 2007.</ref> Some historians believe that some of the pogroms had been organized or supported by the [[Tsar]]ist Russian [[secret police]], the [[Okhranka]].<ref>Edward Radzinsky, ''Nicholas II. Life and Death'' (Russian ed., 1997) p.89</ref> |

| − | By the late 19th century, black Americans had the political experience and confidence to begin to push back against what was, in effect, a gradual decrease in civil rights. In 1888, the [[Tuskegee Institute]] began to assiduously document lynchings, a practice it continued until 1968. <ref name="wexler1">Editorial by Laura Wexler, "A Sorry History: Why an Apology From the Senate Can't Make Amends," Washington Post, Sunday, June 19, 2005, page B1; http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/06/18/AR2005061800075.html</ref> [[Ida B. Wells|Ida B. Wells-Barnett]], a black journalist, was shocked when three of her friends in [[Memphis, Tennessee]], were lynched for opening a [[grocery]] that competed with a white-owned store. Outraged, Wells-Barnett began a global anti-lynching campaign that raised awareness of the American injustice.

| |

| | | | |

| − | Some blacks fought back, believing that the government would never protect them against lynching. During a nationwide rash of race riots in 1919, for example, a young black [[Chicago]]an, Eugene Williams, paddled a raft near a [[Lake Michigan]] beach into "white territory," and drowned after being hit by a rock thrown by a young white man. Witnesses pointed out the killer to a police officer. He refused to make an arrest, and an indignant black mob attacked the officer.<ref name="chicagoriot1">Chicago Daily Tribune, http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/4975/</ref> [[Chicago Race Riot of 1919|Violence broke out across the city]], and while the police stood by, white mobs, many of them organized around Irish clubs, began pulling blacks at random off of trolley cars, attacking black businesses, and beating victims with baseball bats and iron bars. Blacks began to fight back, and eventually 23 blacks and 15 whites were killed.<ref name="whipping"/>

| + | === Israel, West Bank and Gaza Strip === |

| | + | [[Palestine|Palestinian]] lynch mobs have murdered Palestinians suspected of collaborating with [[Israel]]<ref>Yizhar Be'er, Dr. Saleh 'Abdel-Jawad, [http://www.btselem.org/Download/199401_Collaboration_Suspects_Eng.doc Collaborators in the Occupied Territories: Human Rights Abuses and Violations] B’Tselem – The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, January 1994. Accessed 6 November 2006.</ref> |

| | | | |

| − | Black resistance against lynching carried horrible risks. In 1921 in [[Tulsa, Oklahoma]], a group of black citizens attempted to stop a lynch mob from taking a 19-year old black man and assault suspect, [[Dick Rowland]], out of jail. There was a scuffle between a white man and an armed black veteran, and the white man was killed. [[Tulsa Race Riot|Whites retaliated]] by burning 1,256 homes and as many as 200 businesses in the segregated black [[Greenwood, Tulsa, Oklahoma|Greenwood]] district, and leaving a confirmed 39 dead (26 black, 13 white). Recent investigations suggest the number of black deaths may have been much higher. According to some reports, white rioters were shooting at black refugees from airplanes and dropping explosives on them. Dick Rowland was not lynched and was later exonerated.

| + | Israelis have been lynched as well. On October 12, 2000, soon after the outbreak of the [[second Intifada]], Israeli reservists Vadim Norzhich and Yosef Avrahami got lost when they had taken a wrong turn into Palestinian territory in [[Ramallah]]. They blundered into the funeral procession of Palestinians killed by Israeli forces on the previous day, were captured by Palestinians, and taken to a police station. However, a mob gathered outside the police building and broke in, and the two were beaten to death in what was described as a "lynching" by [[Amnesty International]]<ref>Amnesty International, [http://web.amnesty.org/aidoc/ai.nsf/afec99eadc40eff880256e8f0060197c/64f59dc0b44c5fef80256aff0058b1b8/$FILE/ch3.pdf Killings By Palestinians]. Retrieved November 6, 2006.</ref> and the [[BBC]].<ref>Martin Asser, [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/969778.stm Lynch mob's brutal attack]. Retrieved November 6, 2006.</ref> During the killings, the pregnant wife of Vadim Norzich called her husband's cell phone, only to be told "your man is dead" by the Palestinian mob. Their bodies were then thrown out of the window into the hands of a mob of Palestinians, who mutilated the bodies beyond recognition. |

| − | | |

| − | By the 1930s, the rate of lynchings was reduced to ten per year in southern states. With the election of [[Franklin Delano Roosevelt|Franklin D. Roosevelt]] as President in 1932, anti-lynching advocates such as [[Mary McLeod Bethune]] and [[Walter Francis White]] who had campaigned for Roosevelt were hoping for progress toward ending lynching. Senators [[Robert F. Wagner]] and [[Edward P. Costigan]] drafted a bill (the Costigan-Wagner bill) to require local authorities to protect prisoners from lynch mobs. The proposed bill, which would have made lynching a federal as opposed to state crime, was blocked by the virtually all Southern senators and congressmen, who used a [[filibuster]] to prevent a vote on the Costigan-Wagner bill. A lynching in [[Miami, Florida]], affected the political atmosphere of the bill. On July 19, 1935, Rubin Stacy, a homeless African-American farmer, was knocking on doors begging for food. Marion Jones complained to the authorities. Six Dade county deputies were bringing Stacy to jail when he was killed by a lynch mob. Because Stacy's original actions were so innocuous, lynching opponents considered Stacy's murder an egregious example. Nevertheless, Roosevelt did not support the bill, believing that it would cost him the votes of Southern whites, and thus the [[U.S. presidential election, 1936|1936 election]]. In 1939, Roosevelt did create the Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department, which made efforts to combat lynching but failed to win any convictions until 1946.<ref name="wexler2">Wexler, Laura. ''Fire in a Canebrake: The Last Mass Lynching in America'', New York: Scribner, 2003</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | In the 1930s, [[communism|communist]] organizations, including a legal defense organization called the [[International Labor Defense]] (ILD), became active in the anti-lynching cause (see [[The Communist Party and African-Americans]]). The ILD defended the [[Scottsboro Boys]], and three black men accused of rape in Tuscaloosa in 1933. In the Tuscaloosa case, two of the defendants were lynched under circumstances that suggested police complicity, and the ILD lawyers themselves narrowly escaped lynching. Black Americans in general remained unreceptive toward communism, however, and the ILD lawyers aroused passionate hatred among many southerners. In a typical remark to an investigator, a white Tuscaloosan said, "For New York Jews to butt in and spread communistic ideas is too much."<ref name="whipping"/>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Federal action===

| |

| − | President [[Theodore Roosevelt]] made public statements against lynching in his sixth annual [[State of the Union]] message on December 4, 1906; triggered a [[filibuster]] in the [[United States Senate]] in 1902 during the consideration of his "Philippines Bill" by intimating that lynching was taking place there; and refrained from commenting on the use of the issue in southern political campaigns in 1903, although he did make public a letter he wrote to Governor [[Winfield T. Durbin]] of [[Indiana]] where he said:

| |

| − | | |

| − | ::: {{cquote|My Dear Governor Durbin, ...permit me to thank you as an American citizen for the admirable way in which you have vindicated the majesty of the law by your recent action in reference to lynching... All thoughtful men... must feel the gravest alarm over the growth of lynching in this country, and especially over the peculiarly hideous forms so often taken by mob violence when colored men are the victims – on which occasions the mob seems to lay more weight, not on the crime but on the color of the criminal... There are certain hideous sights which when once seen can never be wholly erased from the mental retina. The mere fact of having seen them implies degradation... Whoever in any part of our country has ever taken part in lawlessly putting to death a criminal by the dreadful torture of fire must forever after have the awful spectacle of his own handiwork seared into his brain and soul. He can never again be the same man.}} Roosevelt also publicly commented on the [[Wilmington, Delaware]] lynching of [[George White (Lynch Victim)|George White]] that took place on June 12, 1903.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Durbin had successfully used the [[United States National Guard|National Guard]] to disperse the lynchers, and he publicly declared that the accused murderer—a black man—was entitled to a fair trial. For his efforts, Roosevelt lost a lot of political support among white people—especially in the South—and received threats sufficient that his [[United States Secret Service|Secret Service]] detail had to be increased.<ref name="increased">Morris, Edmund; '''Theodore Rex'''; pp. 110-11, 246-49, 250, 258-59, 261-62, 472.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==World War II to present==

| |

| − | [[Image:fbi-lynching-poster.jpg|thumb|200px|right|FBI poster asking for information in the 1946 lynching at Moore's Ford Bridge, Georgia.]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Federal action===

| |

| − | After [[World War II]], the federal government began to take its first productive actions against lynching.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In 1946, the Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department gained its first successful prosecution against a lyncher. Florida constable Tom Crews was sentenced to a $1,000 fine and one year in prison for civil rights violations in the killing of a black farm worker.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In 1946, a mob of white men shot and killed two young black men and two young black women near Moore's Ford Bridge in [[Walton County, Georgia]]. The savagery of this lynching shocked the nation and was a key factor that led President [[Harry Truman]] to make civil rights a priority.<ref name="wexler2">Wexler, 2003.</ref> In 1947, the Truman Administration published a report titled "''[[To Secure These Rights]]''," which advocated, among other civil rights reforms, making lynching a federal crime. Truman had paid a $10 membership fee to join the Ku Klux Klan in 1924, but at a meeting with a Klan officer arranged by Truman's friend, Klansman Edgar Hinde, the Klan officer demanded that Truman pledge not to hire any Catholics if he was reelected as county judge; Truman refused, because many of the men he had commanded in World War I had been Catholic, and his membership fee was returned,<ref name="trumanklan">Wade, 1987, p. 196, gives essentially this version of the events but implies that the meeting was a regular Klan meeting, rather than an individual meeting between Truman and a Klan organizer. An interview with Hinde at the Truman Library's web site ([http://www.trumanlibrary.org/oralhist/hindeeg.htm http://www.trumanlibrary.org/oralhist/hindeeg.htm], retrieved June 26, 2005) portrays it as a one-on-one meeting at the Hotel Baltimore with a Klan organizer named Jones. Truman's biography, written by his daughter (Truman, 1973), agrees with Hinde's version but does not mention the $10 initiation fee; the same biography reproduces a telegram from O.L. Chrisman stating that reporters from the Hearst papers had questioned him about Truman's past with the Klan, and that he had seen Truman at a Klan meeting, but that "if he ever became a member of the Klan I did not know it."</ref> and he was later much reviled by the Klan for his civil rights activities. In April 2006, the [[Federal Bureau of Investigation|FBI]] confirmed that it has an investigation in progress relating to the 1946 Moore's Ford case.<ref name="bluestein">{{cite news | first=Greg, Associated Press | last=Bluestein | title=FBI reexamines '46 lynchings by white mob | date=April 14, 2006 | publisher=Boston Globe | url=http://www.boston.com/news/nation/articles/2006/04/14/fbi_reexamines_46_lynchings_by_white_mob/ }}</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Lynching, red-baiting, and the cold war===

| |

| − | | |

| − | In the period after World War II, with the beginning of the [[Cold War]], the [[Soviet Union]] made effective use of the existence of lynching in the U.S. as propaganda, and lynching began to be seen as an embarrassment to the U.S., which was becoming a global power. [[Paul Robeson]], in a tense meeting with Truman in 1946, urged him to take action against lynching and began to be attacked in the press for his communism. In 1951, the [[Civil Rights Congress]] (CRC) made a presentation on lynching to the United Nations entitled "We Charge Genocide," which argued that the federal government, by its failure to act against lynching, was guilty of [[genocide]] under Article II of the [[Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide|UN Genocide Convention]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | Because of the Soviet exploitation of lynching for propaganda purposes, there was a tendency in right-wing government circles to portray anti-lynching groups as communist, and although there was sometimes some truth to these claims (Robeson was a communist, and the CRC had been created by a merger of the communist ILD with another group), the label was applied indiscriminately. Even [[Albert Einstein]] was branded a communist sympathizer by the FBI, because of his membership in such "communist-front" organizations as Robeson's [[American Crusade Against Lynching]].<ref name="einstein">Fred Jerome, ''The Einstein File'', St. Martin's Press, 2000; foia.fbi.gov/foiaindex/einstein.htm</ref> In one egregious example, the FBI spread false information in the press that lynching victim [[Viola Liuzzo]] was a member of the Communist Party and had abandoned her five children in order to have sexual relationships with African Americans involved in the civil rights movement.<ref name="liuzzosmear">Detroit News, September 30, 2004; http://www.detnews.com/2004/metro/0409/30/c01-289311.htm</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Civil Rights Movement===

| |

| − | By the 1950s, the [[American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)|Civil Rights Movement]] was gaining momentum. A case that sparked public outrage was that of [[Emmett Till]], a fourteen-year-old Chicagoan who was spending the summer with relatives in the South, and was mutilated and killed for allegedly having whistled at a white woman.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In 1964, [[Mississippi civil rights worker murders|three civil rights workers were lynched]] by white racists in [[Neshoba County, Mississippi]]. [[Michael Schwerner]], [[Andrew Goodman]] of [[New York]], and [[James Chaney]] from [[Meridian, Mississippi]], members of the [[Congress of Racial Equality]], were dedicated to non-violent direct action against racial discrimination. They disappeared in June while investigating the arson of a black church being used as a "Freedom School." Their bodies were found six weeks later in a partially constructed dam near [[Philadelphia, Mississippi]]. In 2005, 80-year-old [[Edgar Ray Killen]] was convicted of manslaughter for the killings and sentenced to 60 years in [[prison]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===After the Civil Rights Movement===

| |

| − | [[Image:Lynching-of-michael-donald.jpg|thumb|200px|The lynching of Michael Donald, 1981.]]Although lynchings became much more rare in the era following the civil rights movement, they do still occur sometimes. In 1981, KKK members in Alabama randomly picked out a nineteen-year-old black man, [[Michael Donald]], and murdered him in retaliation for a jury's acquittal of a black man accused of murdering a police officer. The Klansmen were eventually caught, prosecuted, and convicted, and a seven million dollar judgment in a subsequent civil suit bankrupted a subgroup of the Klan, the United Klans of America.<ref name="donald">[http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USAkkk.htm http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USAkkk.htm], retrieved June 26, 2005.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | In 1998, [[James Byrd, Jr.]] was lynched by [[Shawn Allen Berry]], [[Lawrence Russel Brewer]], and [[John William King]], in [[Jasper, Texas|Jasper]], [[Texas]]. Byrd, a 49-year-old father of three who had accepted an early-morning ride home with Berry, King, Brewer, was instead beaten, stripped, chained to a [[pickup truck]], and dragged for almost three miles (5 km). An autopsy suggested that Byrd was alive for much of the dragging and died only after his right arm and head were severed when his body hit a [[culvert]]. [http://www.cnn.com/US/9902/22/dragging.death.03/] The three men dumped their victim's mutilated remains in the town's segregated Black cemetery and then went to a barbeque. [http://www.texasobserver.org/showArticle.asp?ArticleID=275] Many of the aspects of this modern lynching echo the social customs surrounding older lynchings documented in ''[[Without Sanctuary]]''. King wore a tattoo depicting a black man hanging from a tree as well as [[Nazi]], [[Aryan]] and [[Confederate Knights of America]] symbols.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Local authorities immediately treated the murder as a [[hate crime]] and requested FBI assistance. The murderers were later caught and stood trial. Brewer and King were sentenced to death. Berry received life in prison.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In 2006, five white teenagers—Justin Ashley Phillips, 18; Kenneth Eugene Miller Jr., 18; Lucas Grice, 17; Christopher Scott Cates, 17; and Jerry Christopher Toney, 18—were given various sentences for the second degree lynching of [[Isaiah Clyburn]], 17, a young black man in South Carolina. South Carolina law defies second degree lynching as "[a]ny act of violence inflicted by a mob upon the body of another person and from which death does not result shall constitute the crime of lynching in the second degree and shall be a felony. Any person found guilty of lynching in the second degree shall be confined at hard labor in the State Penitentiary for a term not exceeding twenty years nor less than three years, at the discretion of the presiding judge."<ref name="South Carolina law">South Carolina Code of the Law [http://www.scstatehouse.net/code/t16c003.htm], retrieved February 7, 2007.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | On June 13, 2005, the United States Senate formally apologized for its failure in previous decades to enact a federal anti-lynching law, all of which fell victim to filibusters by powerful Southern senators. Prior to the vote, Louisiana Senator [[Mary Landrieu]] noted, "There may be no other injustice in American history for which the Senate so uniquely bears responsibility."<ref name="senate-apology">Washington Post, June 14, 2005, page A12. [http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/06/13/AR2005061301720.html http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/06/13/AR2005061301720.html], retrieved June 26, 2005.</ref> The resolution was passed on a voice vote with 80 senators cosponsoring, causing some to point out that the remaining 20 did not have to take a position on the matter through either cosponsorship or a recorded vote in favor or against. The resolution expresses "the deepest sympathies and most solemn regrets of the Senate to the descendants of victims of lynching, the ancestors of whom were deprived of life, human dignity and the constitutional protections accorded all citizens of the United States."

| |

| − | | |

| − | === Statistics ===

| |

| − | Tuskegee Institute, which is today known as Tuskegee University, is the institution that has been recognized as the official expert charged with documenting lynching since 1882, and has defined conditions that constitute a recognized lynching:

| |

| − | :"There must be legal evidence that a person was ''killed''. That person must have met death ''illegally.'' A group of ''three or more persons'' must have participated in the killing. The group must have acted under the ''pretext of service to Justice, Race, or Tradition."''

| |

| − | Tuskegee remains the single complete source of statistics and records on this crime since 1882, and is the source for all other compiled statistics. As of 1959, which was the last time that their annual Lynch Report was published, a total of 4,733 persons had died as a result of lynching since 1882. To quote the report,

| |

| − | :"Except for 1955, when three lynchings were reported in Mississippi, none has been recorded at Tuskegee since 1951. In 1945, 1947, and 1951, only one case per year was reported. The most recent case reported by the institute as a lynching was that of Emmett Till, 14, a Negro who was beaten, shot to death, and thrown into a river at [[Greenwood, Mississippi]] on August 28, 1955... For a period of 65 years ending in 1947, at least one lynching was reported each year. The most for any year was 231 in 1892. From 1882 to 1901, lynchings averaged more than 150 a year. Since 1924, lynchings have been in a marked decline, never more than 30 cases, which occurred in 1926...."<ref name="1926...">1959 Tuskegee Institute lynch Report as reported in the Montgomery Advertiser; April 26, 1959, and published in '''''100 Years Of Lynching''' by Ralph Ginzburg (1962, 1988).</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | The following graph gives the number of lynchings and racially-motivated murders in each decade from 1865 to 1965. Data for 1865-1869 and 1960-1965 are partial decades.

| |

| − | <ref name="lynching-numbers">data compiled from [http://users.bestweb.net/~rg/lynching_century.htm http://users.bestweb.net/~rg/lynching_century.htm], retrieved June 26, 2005</ref>

| |

| − | [[Image:Lynchings-graph.png]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | The same source gives the following statistics for the period from 1882 to 1951. 88% of victims were black and 10% were white. 59% of the lynchings occurred in the Southern states of [[Kentucky]] (neutral in the Civil War), [[North Carolina]], [[South Carolina]], [[Tennessee]], [[Arkansas]], [[Louisiana]], [[Mississippi]], [[Alabama]], [[Georgia (U.S. state)|Georgia]], and [[Florida]]. Lynching was not uncommon in the West and Midwest but was virtually nonexistent in the northeast, except for [[Wilmington, Delaware]] (June 12, 1903); [[Port Jervis, New York]], (June 2, 1892); and [[Coatesville, Pennsylvania]] (May 23, 1891; December 13, 1899; and August 13, 1911).

| |

| − | | |

| − | The most common reasons given for the lynchings are murder and rape, but as documented by Ida B. Wells, such charges were often pretexts for lynching blacks who violated Jim Crow etiquette or engaged in economic competition with whites. Other common reasons given include arson, theft, assault, and robbery; sexual transgressions (miscegenation, adultery, cohabitation); "race prejudice," "race hatred," "racial disturbance;" informing on others; "threats against whites;" and violations of the color line ("attending white girl," "proposals to white woman").

| |

| − | | |

| − | === Popular culture ===

| |

| − | | |

| − | In ''[[The Virginian (novel)|The Virginian]]'', a seminal novel that helped create the genre of [[American Old West|Western]] [[novel]]s in the U.S., the protagonist participates in the lynching of an admitted cattle thief, who had been his close friend, during the [[Johnson County War]]. The lynching is represented as a necessary response to the government's corruption and lack of action, but the protagonist feels it to be a horrible duty. He is especially stricken by the bravery with which the thief faces his fate, and the heavy burden it places on his heart forms the emotional core of the story.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In ''[[To Kill a Mockingbird]]'', Tom Robinson, a black man wrongfully accused of rape, narrowly escapes lynching because of his lawyer's bravery, and the disarmingly innocent behavior of the lawyer's daughter. The lawyer tells his daughter that he is not angry at the mob, because once the feeling of mob violence gets into people, they do not act normally. Robinson is later killed while attempting to escape from prison, after having been wrongfully convicted.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In ''[[Fury (1936 movie)|Fury]]'', German expatriate [[Fritz Lang]] depicts a lynch mob hanging innocent men, apparently modeled on a [[Brooke Hart|1933 lynching]] in [[San Jose, California]], that was captured on [[newsreel]] footage and in which [[Governor of California]] [[James Rolph]] refused to intervene.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In ''[[The Ox-Bow Incident]]'', two drifters are drawn into a posse formed to find the murderer of a local man, and suspicion centers on three innocent cattle [[rustler]]s who are then lynched, deeply affecting the drifters. The novel was filmed in 1943 as a wartime defense of American values versus the characterization of [[Third Reich|Nazi Germany]] as mob rule.

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Regina M. Anderson]]'s ''Climbing Jacob's Ladder'' was a play performed by the [[Krigwa players]], a Harlem theater company, about a lynching. Several lynchings are depicted in [[Peter Matthiessen]]'s ''Killing Mr. Watson'' trilogy.

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Lynd Ward]]'s 1932 book ''Wild Pilgrimage'' (printed in woodblock prints, with no text) includes three prints of the lynching of several black men.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Among artistic works referring to lynching is the [[Billie Holiday]] song "[[Strange Fruit]]," written by [[Abel Meeropol]] in 1939:

| |

| − | :''Southern trees bear strange fruit, blood on the leaves and blood at the roots. Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze, strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees. Pastoral scene of the gallant south, the bulging eyes and the twisted mouth. Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh. Then the sudden smell of burning flesh. Here is fruit for the crows to pluck, for the rain to gather, for the wind to suck, for the sun to rot, for the trees to drop, here is a strange and bitter crop.''

| |

| − | | |

| − | The stark, disturbing lyrics were rejected by Holiday's label, but she recorded it independently; the song became an anthem for the anti-lynching movement which joined the groundswell of the [[American civil rights movement]]. A documentary, also entitled ''[http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/strangefruit/ Strange Fruit]'', has aired on U.S. television.

| |

| − | | |

| − | The song has been performed by other artists, including [[Nina Simone]] and [[Cassandra Wilson]]. It was also [[remix]]ed by the British artist [[Tricky]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | === Clarence Thomas ===

| |

| − | The word ''lynching'' returned to popular culture with the nomination to the [[Supreme Court of the United States|U.S. Supreme Court]] of [[Clarence Thomas]], an African-American government attorney nominated by the [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] President [[George H.W. Bush]] and supported by Republican Senators. His nomination received heavy criticism from [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic]] Senators on the [[United States Senate Judiciary Committee|Judiciary Committee]], and in particular allegations of [[sexual harassment]] of a female subordinate, [[Anita Hill]], while he was head of the [[Equal Employment Opportunity Commission]]. Frustrated with the detailed and embarrassing questioning, Thomas appeared before the committee and shot back a prepared statement:

| |