Pope Gregory IX

m |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) m |

||

| (59 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Copyedited}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{epname|Pope Gregory IX}} | ||

{{Infobox Pope| | {{Infobox Pope| | ||

English name=Gregory IX| | English name=Gregory IX| | ||

| Line 11: | Line 12: | ||

dead=dead|death_date={{death date|1241|8|22|mf=y}}| | dead=dead|death_date={{death date|1241|8|22|mf=y}}| | ||

deathplace=[[Rome]], [[Italy]]| | deathplace=[[Rome]], [[Italy]]| | ||

| − | + | }} | |

| − | + | '''Pope Gregory IX''', born '''Ugolino di Conti''', was [[pope]] from March 19, 1227 to August 22, 1241. A nephew of Pope [[Innocent III]], he was educated at the [[University of Paris]] and came to prominence under [[Honorius III]]. | |

| − | + | A man of unquestioned personal piety, he was a supporter of the new monastic orders led by [[Saint Francis]] and [[Saint Dominic]]. However, his [[papacy]] is most remembered for his bitter and often violent power struggle against Emperor [[Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor|Frederick II]], whom he considered lax in his duty as a [[crusades|crusader]]. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Gregory was also a harsh opponent of all kinds of [[heresy]], and it was he who created the papal [[Inquisition]] under the supervision of the [[Dominicans]]. Intellectually, his promulgation of a new collection of papal decretals laid an important foundation for Catholic legal tradition which lasted for more than six centuries, and he restored the right of Catholic scholars to use [[Aristotle|Aristotelean]] [[physics]] and [[metaphysics]] in academic discourse. | ||

| − | + | ==Biography== | |

| + | ===Early years=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Gregory IX.jpg|thumb|left|Illustrated manuscript depicting Pope Gregory IX]] | ||

| + | Ugolino was born in [[Anagni]] around 1145. He received his education at the universities of [[Paris]] and [[Bologna]]. After his uncle [[Innocent III]]'s accession to the papal throne in January 1198, Ugolino was appointed papal chaplain, then archpriest of Saint [[Peter's Basilica]], and finally cardinal-[[deacon]] of the Roman church of Sant Eustachio in 1198. In May, 1206, he was promoted to [[cardinal bishop]] of Ostia. A year later he became a papal ambassador to Germany during the succession struggle following the death of Emperor [[Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor|Henry VI]]. | ||

| − | == | + | After the death of Innocent III in 1216, Ugolino was instrumental in the election of Pope [[Honorius III]]. During Honorius' papacy, Ugolino became a leading preacher of the [[Crusades|Fifth Crusade]]. In January, 1217, Honorius III made Ugolino plenipotentiary legate for [[Lombardy]] and [[Tuscia]] and entrusted him with preaching the crusade in those territories. He became dean of the [[College of Cardinals]] in 1219 and was also archpriest of the [[Vatican Basilica]]. Ugolino appreciated the role of the emerging mendicant orders, and at the request of the future [[Saint Francis]], Pope Honorius appointed Ugolino protector of the Franciscan order in 1220. |

| + | |||

| + | At the coronation of Emperor [[Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor|Frederick II]] in Rome in 1220, the emperor accepted the cross from Ugolino and made the vow to embark soon for the Holy Land on crusade. On March 14, 1221, Honorius commissioned Ugolino to preach the crusade also in Central and Upper Italy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | After the death of Honorius III on March 18, 1227, the cardinals could not immediately reach a decision on a new pope and decided on a compromise procedure empowering three cardinals to act as electors. Two of the three were Ugolino and Conrad of Urach. The other two cardinals apparently nominated Conrad, but he refused to accept since it might appear that he had elected himself. After this, on March 19, Ugolino was elected unanimously, although he was already more than 80 years of age. He took the name of Gregory IX. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Papacy== | ||

| + | ===Struggles with Frederick II=== | ||

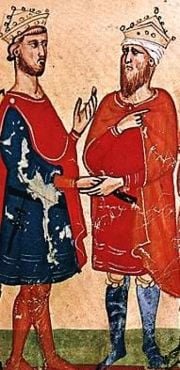

| + | [[Image:Al-Kamil Muhammad al-Malik and Frederick II Holy Roman Emperor.jpg|thumb|180px|[[Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor|Frederick II]] negotiates with Sultan Al-Kamil of Egypt]] | ||

| + | One of Gregory IX's first acts as pope was to move against [[Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor|Frederick II]] for failing to fulfill his vow to involve himself personally in the [[Crusades]]. Frederick and his army had set sail from Brindisi for [[Acre]] in the Holy Land, but an epidemic forced Frederick to return to Italy. Gregory, sensing the same lack of resolve that kept Frederick from fulfilling his earlier vow to go on crusade, placed him under a ban of [[excommunication]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Frederick II appealed to the sovereigns of Europe concerning Gregory's harsh treatment of him. His imperial manifesto was read publicly by his [[Ghibelline]] allies in Rome, and the imperial party in Rome rose in protest against the [[pope]]. Gregory IX now publicly declared the emperor to be excommunicated on March 23, 1228. In reaction, a pro-imperial mob openly insulted the pope and forced him to flee from Rome to [[Perugia]]. In [[Germany]], the pope's actions had little effect. Only one bishop published his decree of excommunication against the emperor, and nearly all the princes and bishops remained faithful to the Frederick. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Determined to prove that he had intended to go on crusade all along, Frederick now embarked for the [[Holy Land]] with a small army. The pope, however, denied that an excommunicated emperor had a right to undertake a [[holy war]]. He refused his blessing and released the crusaders from their oath of allegiance to Frederick. Despite dwindling support, Frederick was able to conquer [[Cyprus]] and successfully negotiated with Sultan [[Al-Kamil]] of [[Egypt]] for [[Jerusalem]], resulting in his temporary recognition as king of the Holy City. | ||

| − | + | Meanwhile, a violent dispute with Rainald of Urslingen, the imperial governor of Spoleto, had caused Gregory to further suspect the emperor. Gregory sent his own forces to invade imperial territory in [[Sicily]]. In June, 1229, Frederick II returned from the Holy Land, routed the papal army in Sicily, and made new overtures of peace to the pope. Gregory, still a fugitive in Perugia since 1228, returned to Rome in February, 1230. A treaty was concluded at [[San Germano]] between the pope and the emperor, and on August 28 the two leaders met at Anagni and completed their reconciliation, at least temporarily. | |

| − | + | [[Image:B Gregor IX2.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Gregory IX excommunicates a heretic]] | |

| + | In the long term, however, the papacy as conceived by Gregory IX and the empire as conceived by Frederick II could not exist together in peace. Moreover, the struggle between the [[Guelphs]], supporting the papacy, and the [[Ghibellines]], supporting the emperor, was intensifying. Consequently, the pope was again driven from his own capital by a pro-imperial revolt in June 1232. He was compelled to take refuge at [[Anagni]] and beg for the aid of Frederick II. A truce was arranged and there was peace between pope and emperor for several years. However, when Frederick II defeated the [[Lombard League]] in 1239, the possibility that he might dominate all of Italy became a very real threat. A new outbreak of hostility led to a fresh excommunication of the emperor and to a prolonged war. | ||

| − | + | Gregory IX now denounced Frederick II as a [[heresy|heretic]] and summoned a council at Rome to give point to his [[anathema]]. To frustrate these plans, Frederick II attempted to capture or sink as many ships carrying [[prelates]] to the synod as he could. The struggle was only terminated by the death of Gregory IX on August 22, 1241. It would be his successor, [[Innocent IV]] who finally brought an end to the [[Hohenstaufen]] threat by declaring a [[crusade]] against the emperor. | |

| − | + | ==Other activities== | |

| + | [[Image:People burned as heretics.jpg|thumb|250px|Cathars burned at the stake during the [[Albigensian Crusade]].]] | ||

| + | ===Against 'heretics' and 'schismatics'=== | ||

| + | Gregory IX believed the problem of [[heresy]] needed serious attention and was not content with leaving it to the local [[bishop]]s. He thus extended central control over the suppression of heresy, and in 1231, he established the papal [[Inquisition]] to deal with it, placing the [[Dominicans]] in charge of the process. | ||

| − | + | Gregory IX's policy toward heretics was a severe one. Those who opposed Church tradition, in those times, were looked upon as traitors and punished accordingly. Upon the request of King [[Louis IX]] of France, Gregory sent Cardinal Romanus as legate to assist the king in his crusade against the [[Albigensian Crusade|Albigenses]] (also known as the Cathars). During his papacy a number of the members of the reformist [[Pataria]] sect were arrested in Rome and burned at the stake in 1231, with others imprisoned in the Benedictine monasteries of [[Monte Cassino]] and Cava. | |

| − | Gregory | + | Gregory also endorsed the [[Northern Crusades]] and the [[Teutonic Order]]'s attempts to conquer [[Eastern Orthodox Church|Orthodox]] [[Russia]]. Unlike some other popes, however, he did not approve of the use of [[torture]] as a tool for the investigation of heresy or for [[penance]]. |

| − | + | ===Legal and intellectual reforms=== | |

| + | A remarkably skillful and learned lawyer, Gregory IX initiated the ''Nova Compilatio decretalium'' (New Compilation of Decretals), which was promulgated in numerous copies in 1234. This work was the culmination of a long process of systematizing the mass of papal pronouncements that had accumulated since the early [[Middle Ages]], a process that had been under way since the first half of the twelfth century and had come to fruition in the ''[[Decretum]]'', compiled by [[Gratian (jurist)|Gratian]] and published in 1140. Gregory's supplement completed Gratian's work, and helped provide the foundation for the mature papal legal theory. | ||

| − | His | + | His [[Papal bull|bull]] ''[[University of Paris strike of 1229|Parens scientiarum]]'' of 1231 resolved differences between the philosophically minded professors of his alma mater, the [[University of Paris]], and more conservative local authorities. He warned the professors against the growing tendency of subjecting theology to philosophy by making the truth of the mysteries of faith dependent on philosophical proofs. On the other hand, he removed the prohibition of Aristotelean [[physics]] and [[metaphysics]] as the basis of [[scholasticism|scholastic philosophy]]. |

| − | Gregory IX | + | ===Support for saints and new orders=== |

| + | [[Image:Hermann von Salza Painting.jpg|thumb|150px|Hermann von Salza Painting, grand master of the [[Teutonic Order]] under Gregory IX]] | ||

| + | Gregory IX had been a personal friend and supporter of the future saints [[Francis of Assisi|Francis]] and [[Saint Dominic|Dominic]]. Among the ten cardinals he appointed were several members of these new orders, who rejected personal wealth and brought a reforming spirit to the College of Cardinals. Gregory [[canonization|canonized]] saints [[Elisabeth of Hungary]], Dominic, [[Anthony of Padua]], and Francis of Assisi. | ||

| − | + | For Gregory, the mendicant orders constituted an excellent means of counteracting the love of luxury that had affected many clerics, and were also a powerful weapon for suppressing [[heresy]] among the masses. His support of the rising mendicant orders did not, however, cause him to neglect the older ones. In 1227, he approved the old privileges of the Camaldolese, in the same year he introduced the Premonstratensians into Livonia and Courland. In April, 1229, he gave new statutes to the [[Carmelites]]. He financially and otherwise assisted the [[Cistercians]] and the [[Teutonic Order]]. In January, 1235, he approved the [[Order of Our Lady of Mercy]] for the redemption of non-Christian captives. He also sent missionaries to Tunis, Morocco, and other places, where some suffered martyrdom. He also worked to alleviate the hard lot of the Christians in the Holy Land. | |

| − | Gregory IX | + | ===Relations with the Orthodox Churches=== |

| + | For a time Gregory IX lived in hope that he might effect a reunion of the [[Roman Catholic|Roman Catholic]] and [[Eastern Orthodox Church]]es. Germanos, Patriarch of Constantinople, had written a letter to Gregory, in which he acknowledged the papal primacy, but also complained of the persecution of the Greeks by the Catholic crusaders. Gregory IX sent him a cordial answer and commissioned four learned monks (two Franciscans and two Dominicans) to discuss the possibility of reunion. | ||

| − | + | The papal messengers were kindly received both by the Eastern Emperor Vatatzes and by Germanos. However, the patriarch indicated that he could make no concessions on matters of faith consulting of the patriarchs of [[Jerusalem]], [[Antioch]], and [[Alexandria]]. A [[synod]] of the patriarchs was held at Nympha in Bithynia, to which the papal messengers were invited. The [[filioque clause]] proved an insurmountable obstacle, however, and the patriarchs also insisted that the Roman practice of consecrating unleavened bread was unacceptable. Thus Gregory IX failed, like many other popes before and after him, in his efforts to reunite the two churches. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Legacy== |

| − | + | Gregory IX's power struggle against the secular power of the emperor was nothing new for the [[papacy]], but his open warfare against Frederick II created an ugly spectacle. His creation of the papal [[Inquisition]] under the leadership of the [[Dominicans]] likewise left an unfortunate legacy, in which the papacy would forever be linked with [[heresy]]-hunting and the deaths of thousands who dared to disagree with [[Rome]] on matters of doctrine and practice. | |

| − | + | On the other hand, his standards of person piety were beyond reproach, and his support of the mendicant orders constituted a step toward reforming the luxurious culture of the [[Catholic Church]]'s upper echelons. His restoration of the right of scholars to use [[Aristotle]] as an authority was an important and progressive intellectual reform. Finally, his promulgation of a new collection of papal decretals in 1234 constituted an important foundation for Catholic ecclesiastical law which lasted well into the twentieth century. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Pope| | {{Pope| | ||

Predecessor=[[Pope Honorius III|Honorius III]]| | Predecessor=[[Pope Honorius III|Honorius III]]| | ||

Successor=[[Pope Celestine IV|Celestine IV]]|Dates=1227–41}} | Successor=[[Pope Celestine IV|Celestine IV]]|Dates=1227–41}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==See also== | ||

| + | *[[Crusades]] | ||

| + | *[[Albigensian Crusade]] | ||

| + | *[[Dominicans]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | *Abulafia, David. ''Frederick II: A Medieval Emperor''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 9780195080407 | ||

| + | *Christiansen, Eric H. ''The Northern Crusade: The Baltic and the Catholic Frontier, 1100-1525''. New studies in medieval history. London: Macmillan, 1980. ISBN 9780333263952 | ||

| + | *Hartmann, Wilfried, and Kenneth Pennington. ''The History of Medieval Canon Law in the Classical Period, 1140-1234: From Gratian to the Decretals of Pope Gregory IX''. History of medieval canon law. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2008. ISBN 9780813214917 | ||

| + | * Hinnebusch, William A. ''The History of the Dominican Order''. Alba House, 1966. ISBN 9780818902666 | ||

| + | *Pennington, Kenneth. ''Popes, Canonists, and Texts, 1150-1550''. Aldershot, Hampshire, Great Britain: Variorum, 1993. ISBN 9780860783879 | ||

| + | *Proctor, David J. ''Imperial Christ: Perceptions of Authority in Medieval Western Europe''. Thesis (M.A.)—Tufts University, 2001. {{OCLC|190834105}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved July 17, 2017. | ||

| + | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06796a.htm Pope Gregory IX] ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. | ||

| + | |||

{{Popes}} | {{Popes}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:religion]] | [[Category:religion]] | ||

| − | + | [[Category:popes]] | |

| − | |||

[[Category:biography]] | [[Category:biography]] | ||

[[Category:history]] | [[Category:history]] | ||

[[Category:religious figures]] | [[Category:religious figures]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Christianity]] | ||

{{Credit|205298565}} | {{Credit|205298565}} | ||

Latest revision as of 21:25, 17 July 2017

| Gregory IX | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Ugolino di Conti |

| Papacy began | March 19, 1227 |

| Papacy ended | August 22, 1241 |

| Predecessor | Honorius III |

| Successor | Celestine IV |

| Born | between 1145 and 1170 Anagni, Italy |

| Died | August 22 1241 Rome, Italy |

Pope Gregory IX, born Ugolino di Conti, was pope from March 19, 1227 to August 22, 1241. A nephew of Pope Innocent III, he was educated at the University of Paris and came to prominence under Honorius III.

A man of unquestioned personal piety, he was a supporter of the new monastic orders led by Saint Francis and Saint Dominic. However, his papacy is most remembered for his bitter and often violent power struggle against Emperor Frederick II, whom he considered lax in his duty as a crusader.

Gregory was also a harsh opponent of all kinds of heresy, and it was he who created the papal Inquisition under the supervision of the Dominicans. Intellectually, his promulgation of a new collection of papal decretals laid an important foundation for Catholic legal tradition which lasted for more than six centuries, and he restored the right of Catholic scholars to use Aristotelean physics and metaphysics in academic discourse.

Biography

Early years

Ugolino was born in Anagni around 1145. He received his education at the universities of Paris and Bologna. After his uncle Innocent III's accession to the papal throne in January 1198, Ugolino was appointed papal chaplain, then archpriest of Saint Peter's Basilica, and finally cardinal-deacon of the Roman church of Sant Eustachio in 1198. In May, 1206, he was promoted to cardinal bishop of Ostia. A year later he became a papal ambassador to Germany during the succession struggle following the death of Emperor Henry VI.

After the death of Innocent III in 1216, Ugolino was instrumental in the election of Pope Honorius III. During Honorius' papacy, Ugolino became a leading preacher of the Fifth Crusade. In January, 1217, Honorius III made Ugolino plenipotentiary legate for Lombardy and Tuscia and entrusted him with preaching the crusade in those territories. He became dean of the College of Cardinals in 1219 and was also archpriest of the Vatican Basilica. Ugolino appreciated the role of the emerging mendicant orders, and at the request of the future Saint Francis, Pope Honorius appointed Ugolino protector of the Franciscan order in 1220.

At the coronation of Emperor Frederick II in Rome in 1220, the emperor accepted the cross from Ugolino and made the vow to embark soon for the Holy Land on crusade. On March 14, 1221, Honorius commissioned Ugolino to preach the crusade also in Central and Upper Italy.

After the death of Honorius III on March 18, 1227, the cardinals could not immediately reach a decision on a new pope and decided on a compromise procedure empowering three cardinals to act as electors. Two of the three were Ugolino and Conrad of Urach. The other two cardinals apparently nominated Conrad, but he refused to accept since it might appear that he had elected himself. After this, on March 19, Ugolino was elected unanimously, although he was already more than 80 years of age. He took the name of Gregory IX.

Papacy

Struggles with Frederick II

One of Gregory IX's first acts as pope was to move against Frederick II for failing to fulfill his vow to involve himself personally in the Crusades. Frederick and his army had set sail from Brindisi for Acre in the Holy Land, but an epidemic forced Frederick to return to Italy. Gregory, sensing the same lack of resolve that kept Frederick from fulfilling his earlier vow to go on crusade, placed him under a ban of excommunication.

Frederick II appealed to the sovereigns of Europe concerning Gregory's harsh treatment of him. His imperial manifesto was read publicly by his Ghibelline allies in Rome, and the imperial party in Rome rose in protest against the pope. Gregory IX now publicly declared the emperor to be excommunicated on March 23, 1228. In reaction, a pro-imperial mob openly insulted the pope and forced him to flee from Rome to Perugia. In Germany, the pope's actions had little effect. Only one bishop published his decree of excommunication against the emperor, and nearly all the princes and bishops remained faithful to the Frederick.

Determined to prove that he had intended to go on crusade all along, Frederick now embarked for the Holy Land with a small army. The pope, however, denied that an excommunicated emperor had a right to undertake a holy war. He refused his blessing and released the crusaders from their oath of allegiance to Frederick. Despite dwindling support, Frederick was able to conquer Cyprus and successfully negotiated with Sultan Al-Kamil of Egypt for Jerusalem, resulting in his temporary recognition as king of the Holy City.

Meanwhile, a violent dispute with Rainald of Urslingen, the imperial governor of Spoleto, had caused Gregory to further suspect the emperor. Gregory sent his own forces to invade imperial territory in Sicily. In June, 1229, Frederick II returned from the Holy Land, routed the papal army in Sicily, and made new overtures of peace to the pope. Gregory, still a fugitive in Perugia since 1228, returned to Rome in February, 1230. A treaty was concluded at San Germano between the pope and the emperor, and on August 28 the two leaders met at Anagni and completed their reconciliation, at least temporarily.

In the long term, however, the papacy as conceived by Gregory IX and the empire as conceived by Frederick II could not exist together in peace. Moreover, the struggle between the Guelphs, supporting the papacy, and the Ghibellines, supporting the emperor, was intensifying. Consequently, the pope was again driven from his own capital by a pro-imperial revolt in June 1232. He was compelled to take refuge at Anagni and beg for the aid of Frederick II. A truce was arranged and there was peace between pope and emperor for several years. However, when Frederick II defeated the Lombard League in 1239, the possibility that he might dominate all of Italy became a very real threat. A new outbreak of hostility led to a fresh excommunication of the emperor and to a prolonged war.

Gregory IX now denounced Frederick II as a heretic and summoned a council at Rome to give point to his anathema. To frustrate these plans, Frederick II attempted to capture or sink as many ships carrying prelates to the synod as he could. The struggle was only terminated by the death of Gregory IX on August 22, 1241. It would be his successor, Innocent IV who finally brought an end to the Hohenstaufen threat by declaring a crusade against the emperor.

Other activities

Against 'heretics' and 'schismatics'

Gregory IX believed the problem of heresy needed serious attention and was not content with leaving it to the local bishops. He thus extended central control over the suppression of heresy, and in 1231, he established the papal Inquisition to deal with it, placing the Dominicans in charge of the process.

Gregory IX's policy toward heretics was a severe one. Those who opposed Church tradition, in those times, were looked upon as traitors and punished accordingly. Upon the request of King Louis IX of France, Gregory sent Cardinal Romanus as legate to assist the king in his crusade against the Albigenses (also known as the Cathars). During his papacy a number of the members of the reformist Pataria sect were arrested in Rome and burned at the stake in 1231, with others imprisoned in the Benedictine monasteries of Monte Cassino and Cava.

Gregory also endorsed the Northern Crusades and the Teutonic Order's attempts to conquer Orthodox Russia. Unlike some other popes, however, he did not approve of the use of torture as a tool for the investigation of heresy or for penance.

Legal and intellectual reforms

A remarkably skillful and learned lawyer, Gregory IX initiated the Nova Compilatio decretalium (New Compilation of Decretals), which was promulgated in numerous copies in 1234. This work was the culmination of a long process of systematizing the mass of papal pronouncements that had accumulated since the early Middle Ages, a process that had been under way since the first half of the twelfth century and had come to fruition in the Decretum, compiled by Gratian and published in 1140. Gregory's supplement completed Gratian's work, and helped provide the foundation for the mature papal legal theory.

His bull Parens scientiarum of 1231 resolved differences between the philosophically minded professors of his alma mater, the University of Paris, and more conservative local authorities. He warned the professors against the growing tendency of subjecting theology to philosophy by making the truth of the mysteries of faith dependent on philosophical proofs. On the other hand, he removed the prohibition of Aristotelean physics and metaphysics as the basis of scholastic philosophy.

Support for saints and new orders

Gregory IX had been a personal friend and supporter of the future saints Francis and Dominic. Among the ten cardinals he appointed were several members of these new orders, who rejected personal wealth and brought a reforming spirit to the College of Cardinals. Gregory canonized saints Elisabeth of Hungary, Dominic, Anthony of Padua, and Francis of Assisi.

For Gregory, the mendicant orders constituted an excellent means of counteracting the love of luxury that had affected many clerics, and were also a powerful weapon for suppressing heresy among the masses. His support of the rising mendicant orders did not, however, cause him to neglect the older ones. In 1227, he approved the old privileges of the Camaldolese, in the same year he introduced the Premonstratensians into Livonia and Courland. In April, 1229, he gave new statutes to the Carmelites. He financially and otherwise assisted the Cistercians and the Teutonic Order. In January, 1235, he approved the Order of Our Lady of Mercy for the redemption of non-Christian captives. He also sent missionaries to Tunis, Morocco, and other places, where some suffered martyrdom. He also worked to alleviate the hard lot of the Christians in the Holy Land.

Relations with the Orthodox Churches

For a time Gregory IX lived in hope that he might effect a reunion of the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches. Germanos, Patriarch of Constantinople, had written a letter to Gregory, in which he acknowledged the papal primacy, but also complained of the persecution of the Greeks by the Catholic crusaders. Gregory IX sent him a cordial answer and commissioned four learned monks (two Franciscans and two Dominicans) to discuss the possibility of reunion.

The papal messengers were kindly received both by the Eastern Emperor Vatatzes and by Germanos. However, the patriarch indicated that he could make no concessions on matters of faith consulting of the patriarchs of Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria. A synod of the patriarchs was held at Nympha in Bithynia, to which the papal messengers were invited. The filioque clause proved an insurmountable obstacle, however, and the patriarchs also insisted that the Roman practice of consecrating unleavened bread was unacceptable. Thus Gregory IX failed, like many other popes before and after him, in his efforts to reunite the two churches.

Legacy

Gregory IX's power struggle against the secular power of the emperor was nothing new for the papacy, but his open warfare against Frederick II created an ugly spectacle. His creation of the papal Inquisition under the leadership of the Dominicans likewise left an unfortunate legacy, in which the papacy would forever be linked with heresy-hunting and the deaths of thousands who dared to disagree with Rome on matters of doctrine and practice.

On the other hand, his standards of person piety were beyond reproach, and his support of the mendicant orders constituted a step toward reforming the luxurious culture of the Catholic Church's upper echelons. His restoration of the right of scholars to use Aristotle as an authority was an important and progressive intellectual reform. Finally, his promulgation of a new collection of papal decretals in 1234 constituted an important foundation for Catholic ecclesiastical law which lasted well into the twentieth century.

| Roman Catholic Popes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Honorius III |

Bishop of Rome 1227–41 |

Succeeded by: Celestine IV |

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abulafia, David. Frederick II: A Medieval Emperor. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 9780195080407

- Christiansen, Eric H. The Northern Crusade: The Baltic and the Catholic Frontier, 1100-1525. New studies in medieval history. London: Macmillan, 1980. ISBN 9780333263952

- Hartmann, Wilfried, and Kenneth Pennington. The History of Medieval Canon Law in the Classical Period, 1140-1234: From Gratian to the Decretals of Pope Gregory IX. History of medieval canon law. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2008. ISBN 9780813214917

- Hinnebusch, William A. The History of the Dominican Order. Alba House, 1966. ISBN 9780818902666

- Pennington, Kenneth. Popes, Canonists, and Texts, 1150-1550. Aldershot, Hampshire, Great Britain: Variorum, 1993. ISBN 9780860783879

- Proctor, David J. Imperial Christ: Perceptions of Authority in Medieval Western Europe. Thesis (M.A.)—Tufts University, 2001. OCLC 190834105

External links

All links retrieved July 17, 2017.

- Pope Gregory IX Catholic Encyclopedia.

| ||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.