Difference between revisions of "Emotion" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (185 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} | ||

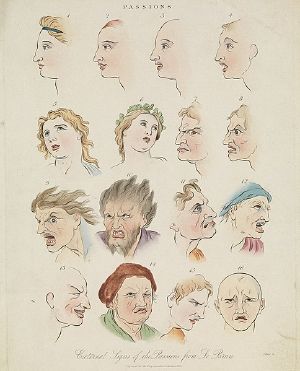

| + | [[File:Sixteen faces expressing the human passions. Wellcome L0068375 (cropped).jpg|thumb|Sixteen faces expressing the human passions – coloured [[engraving]] by J. Pass, 1821, after [[Charles Le Brun]]|300px]] | ||

| + | '''Emotions''' are [[mental state]]s brought on by [[neurophysiology|neurophysiological]] changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of [[pleasure]] or [[suffering|displeasure]]. Emotions are often intertwined with the [[mood (psychology)|mood]], [[temperament]], [[personality psychology|personality]], [[disposition]], or [[creativity]] of the individual experiencing the emotion. | ||

| + | Emotions are complex, involving different components, such as subjective experience, [[cognition|cognitive process]]es, expressive behavior, psychophysiological changes, and instrumental behavior. At one time, academics attempted to identify the emotion with one of the components: [[William James]] with a subjective experience, [[behaviorism|behaviorist]]s with instrumental behavior, [[psychophysiology|psychophysiologist]]s with physiological changes, and so on. More recently, emotion is said to consist of all the components. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Research on emotion currently involves many fields, including [[psychology]], [[medicine]], [[history]], [[sociology]], and [[computer science]]. This reflects the fact that emotions are not only complex in themselves but are also one aspect of the complexity of human nature. | ||

| − | [ | + | == Etymology == |

| + | The word "emotion" dates back to the 1570s, when it was adapted from the French word ''émouvoir'', which means "to stir up," which derives from the Latin ''emovere'' "move out, remove, agitate," from ''ex'' "out" plus ''movere'' "to move." The term was first recorded to refer to "strong feeling" in the 1650s; and was extended to any feeling by 1808.<ref>[https://www.etymonline.com/word/emotion emotion] ''Etymology Online''. Retrieved April 4, 2023.</ref> | ||

| + | == Definitions == | ||

| + | The ''Merriam-Webster'' definition of '''emotion''' is "a conscious mental reaction (such as anger or fear) subjectively experienced as strong feeling usually directed toward a specific object and typically accompanied by physiological and behavioral changes in the body."<ref>[https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/emotion emotion] ''Merriam-Webster''. Retrieved April 5, 2023.</ref> | ||

| + | This modern concept of emotion first emerged in the English language in the nineteenth century: | ||

| + | <blockquote>No one felt emotions before about 1830. Instead they felt other things – 'passions', 'accidents of the soul', 'moral sentiments' – and explained them very differently from how we understand emotions today.<ref> Tiffany Watt Smith, ''The Book of Human Emotions'' (Little, Brown Spark, 2016, ISBN 978-0316265409).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | "Emotion" was introduced into academic discussion as a catch-all term to [[passions (philosophy)|passion]]s, [[feeling|sentiment]]s, and [[affection]]s.<ref>Thomas Dixon, ''From Passions to Emotions: The Creation of a Secular Psychological Category'' (Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0521026695). </ref> | |

| − | + | They are generally understood to be [[mental state]]s brought on by [[neurophysiology|neurophysiological]] changes, variously associated with [[thought]]s, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of [[pleasure]] or [[suffering|displeasure]].<ref>Jaak Panksepp, ''Affective Neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions'' (Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0195178050).</ref><ref> Paul Ekman and Richard J. Davidson (eds.), ''The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions'' (Oxford University Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0195089448).</ref><ref name=Schacter> Daniel L. Schacter, Daniel T. Gilbert, and Daniel M. Wegner, ''Psychology'' (Worth Publishers, 2010, ISBN 978-1429237192).</ref> | |

| − | + | There is currently no scientific consensus on a definition of emotion.<ref> Lisa Feldman Barrett, Michael Lewis, and Jeannette M. Haviland-Jones (eds.), ''Handbook of Emotions'' (The Guilford Press, 2016, ISBN 978-1462525348).</ref> In general, emotions are evoked in response to significant internal and external events.<ref name=Schacter/> | |

| + | Thus, emotions have been described as consisting of a coordinated set of responses, which may include verbal, [[physiology|physiological]], behavioral, and [[nervous system|neural]] mechanisms.<ref name=Fox>Elaine Fox, ''Emotion Science: Cognitive and Neuroscientific Approaches to Understanding Human Emotions'' (Red Globe Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0230005181). </ref> | ||

| − | = | + | Emotion can be differentiated from a number of similar constructs within the field of [[affective neuroscience]]<ref name=Fox/>: |

| + | * [[Feeling]]: not all feelings include emotion, such as the [[feeling#Knowing or not knowing|feeling of knowing]]. In the context of emotion, feelings are best understood as a [[subjectivity|subjective]] representation of emotions, private to the individual experiencing them. | ||

| + | * [[Mood (psychology)|Mood]]s: [[diffusion|diffuse]] affective states that generally last for much longer durations than emotions; they are also usually less intense than emotions and often appear to lack a contextual stimulus. | ||

| + | * [[Affect (psychology)|Affect]]: used to describe the underlying affective experience of an emotion or a mood. | ||

| − | + | == History == | |

| + | Human nature and the accompanying bodily sensations have always been part of the interests of thinkers and philosophers, in both Western and Eastern societies. Emotional states have been associated with the divine and with the [[enlightenment]] of the human mind and body.<ref>Jerome Kagan, ''What is Emotion?: History, measures, and meanings'' (Yale University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0300143096).</ref> The ever-changing actions of individuals and their mood variations were of great importance to most Western philosophers, including [[Aristotle]], [[Plato]], [[Descartes]], [[Aquinas]], [[Machiavelli]], [[Spinoza]], and [[Hobbes]], leading them to propose extensive theories—often competing theories—that sought to explain emotion and the accompanying motivators of human action, as well as its consequences. For example, Descartes defined and investigates the six primary passions ([[wonder (emotion)|wonder]], [[love]], [[hate]], [[desire]], [[joy]], and [[sadness]]) in his philosophical treatise, ''[[The Passions of the Soul]]''.<ref> Rene Descartes, Stephen Voss (trans.), ''The Passions of the Soul'' (Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1989 (original 1649), ISBN 978-0872200357).</ref> | ||

| − | + | In the [[Age of Enlightenment]], Scottish thinker [[David Hume]] proposed a revolutionary argument that sought to explain the main motivators of human action and conduct. He proposed that actions are motivated by "fears, desires, and passions." As he wrote in his book ''[[Treatise of Human Nature]]'' (1739–1740): | |

| + | <blockquote>Reason alone can never be a motive to any action of the will… it can never oppose passion in the direction of the will… The reason is, and ought to be, the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them."<ref>David Hume, ''A Treatise of Human Nature'' (Penguin Classics, 1986 (original 1739–1740), ISBN 978-0140432442).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Hume attempted to explain that reason and further action would be subject to the desires and experience of the self. Later thinkers would propose that actions and emotions are deeply interrelated with social, political, historical, and cultural aspects of reality that would also come to be associated with sophisticated neurological and physiological research on the brain and other parts of the physical body. | |

| − | + | In the nineteenth century, emotions were considered adaptive and were studied from an [[empiricism|empiricist]] perspective. In the late nineteenth century, the most influential theorists were [[William James]] (1842–1910) and [[Carl Lange (physician)|Carl Lange]] (1834–1900). James was an American psychologist and philosopher. In his ''Principles of Psychology'' (1890) he proposed that emotions are the sensation of changes in the body: “the bodily changes follow directly the perception of the exciting fact, and that our feeling of the same changes as they occur IS the emotion.”<ref name=James> William James, ''The Principles of Psychology'' (Harvard University Press, 1983 (original 1890), ISBN 978-0674706255).</ref> His position was that the physiological changes come first and without them, there can be no feeling of emotion, and all that would remain “would be purely cognitive in form, pale, colorless, destitute of emotional warmth.”<ref name=James/> | |

| − | + | Lange was a Danish physician and psychologist. Working independently, they developed a hypothesis on the origin and nature of emotions, referred to as the [[James–Lange theory]]. This states that within human beings, as a response to experiences in the world, the [[autonomic nervous system]] creates physiological events such as muscular tension, a rise in heart rate, perspiration, and dryness of the mouth. Emotions, then, are feelings which come about as a result of these physiological changes, rather than being their cause.<ref> Kendra Cherry, [https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-the-james-lange-theory-of-emotion-2795305 What Is the James-Lange Theory of Emotion?] ''Verywell Mind'', October 20, 2022. Retrieved April 5, 2023.</ref> | |

| − | + | The twentieth century saw many advances in the study of emotions. For example, [[Richard Lazarus]] (1922–2002) specialized in studies of emotion and [[stress]], especially in relation to [[cognition]]; [[Herbert A. Simon]] (1916–2001), included emotions in decision making and [[artificial intelligence]]; [[Robert Plutchik]] (1928–2006) developed a psychoevolutionary theory of emotion; [[Robert C. Solomon]] (1942–2007) contributed to the theories on the philosophy of emotions;<ref> Robert C. Solomon, ''The Passions: Emotions and the Meaning of Life'' (Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1993, ISBN 978-0872202269).</ref> [[Nico Frijda]] (1927–2015) advanced the theory that human emotions serve to promote a tendency to undertake actions that are appropriate in the circumstances;<ref name=Frijda>Nico H. Frijda, ''The Emotions'' (Cambridge University Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0521316002).</ref> and [[Jaak Panksepp]] (1943–2017) pioneered studies in affective neuroscience. | |

| − | + | == Classification == | |

| + | Human beings experience emotion which influence actions, thoughts, and [[behavior]]. Both positive and negative emotions are needed in our daily lives.<ref>W. Gerrod Parrott (ed.), ''The Positive Side of Negative Emotions'' (The Guilford Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1462513338).</ref> A number of models have been proposed to classify emotions. | ||

| − | + | For both theoretical and practical reasons researchers often define emotions according to one or more dimensions. Dimensional models of emotion attempt to conceptualize human emotions by defining where they lie in two or three [[dimension]]s. They often incorporate [[Valence (psychology)|valence]] (good (positive) versus bad (negative) valence) and [[arousal]] or intensity dimensions. Several dimensional models have been proposed. | |

| − | + | For example, [[Wilhelm Wundt|Wilhelm Max Wundt]] proposed in 1897 that emotions can be described by three dimensions: "pleasurable versus unpleasurable," "arousing or subduing," and "strain or relaxation."<ref>Willhelm M. Wundt, ''Outlines of Psychology'' (Cornell University Library, 2009 (original 1897), ISBN 1112410600). </ref> | |

| + | Another approach has been to focus on specifying basic emotions, or categories of emotion which are independent, and then adding the dimensions as modifiers. | ||

| − | + | Several models of the "basic emotions" have been suggested: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * [[William James]] in 1890 proposed four basic emotions: [[fear]], [[grief]], [[love]], and [[Rage (emotion)|rage]], based on bodily involvement.<ref name=James/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * [[Paul Ekman]] identified six basic emotions: [[anger]], [[disgust]], fear, [[happiness]], [[sadness]], and [[surprise]], which can be linked to facial expressions.<ref>Paul Ekman, [https://www.paulekman.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Are-There-Basic-Emotions1.pdf Are There Basic Emotions?] ''Psychological Review'' 99(3) (1992):550-553. Retrieved April 7, 2023.</ref> He later expanded this list of basic emotions, including a range of positive and negative emotions that are not all encoded in facial muscles. The newly included emotions are: [[Amusement]], [[Contempt]], [[Contentment]], [[Embarrassment]], [[Anxiety|Excitement]], [[Guilt (emotion)|Guilt]], [[Pride|Pride in achievement]], [[Relief (emotion)|Relief]], [[Contentment|Satisfaction]], [[Pleasure|Sensory pleasure]], and [[Shame]].<ref name="Ekman 1999">Paul Ekman, "Basic Emotions" in ''Handbook of Cognition and Emotion'' Tim Dalgleish and Mick Power (eds.), ''Handbook of Cognition and Emotion'' (John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1999, ISBN 978-0471978367), 42-45. </ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | * [[Richard Lazarus|Richard and Bernice Lazarus]] in 1996 expanded Ekman's original list to 15 emotions: aesthetic experience, anger, anxiety, compassion, depression, envy, fright, gratitude, guilt, happiness, hope, jealousy, love, pride, relief, sadness, and shame.<ref name=Lazarus> Richard S. Lazarus and Bernice N. Lazarus, ''Passion and Reason: Making Sense of Our Emotions'' (Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0195104615).</ref> | |

| + | * Alan S. Cowen and Dacher Keltner, using statistical methods to analyze emotional states elicited by short videos, identified 27 varieties of emotional experience: admiration, adoration, aesthetic appreciation, amusement, anger, anxiety, awe, awkwardness, boredom, calmness, confusion, craving, disgust, empathic pain, entrancement, excitement, fear, horror, interest, joy, nostalgia, relief, romance, sadness, satisfaction, sexual desire and surprise.<ref>Alan S. Cowen and Dacher Keltner, [https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.1702247114 Self-report captures 27 distinct categories of emotion bridged by continuous gradients] ''The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS)'' 114(38) (September 5, 2017):E7900-E7909. Retrieved April 7, 2023.</ref> | ||

| − | + | == Theories == | |

| + | Emotions are complex. There are various theories on the question of whether or not emotions cause changes in our behavior.<ref name=Schacter/> The physiology of emotion is closely linked to [[arousal]] of the [[nervous system]]. Emotion is often the driving force behind [[motivation]].<ref name=Gaulin/> On the other hand, emotions are not causal forces but simply syndromes of components, which might include motivation, feeling, behavior, and physiological changes, but none of these components is the emotion. Nor is the emotion an entity that causes these components.<ref>Lisa Feldman Barrett and James A. Russell (eds.), ''The Psychological Construction of Emotion'' (The Guilford Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1462516971).</ref> [[George Mandler]] provides an extensive theoretical and empirical discussion of emotion as influenced by cognition, consciousness, and the autonomic nervous system.<ref>George Mandler, ''Mind and Emotion'' (Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company, 1975, ISBN 978-0898743500).</ref><ref>George Mandler, ''Mind and Body: Psychology of Emotion and Stress'' (W W Norton & Co Inc, 1984. ISBN 978-0393953466).</ref> | ||

| − | [[ | + | === Early theories === |

| + | In [[Stoicism|Stoic]] theories, normal emotions (like delight and fear) are described as irrational impulses which come from incorrect appraisals of what is "good" or "bad." Alternatively, there are "good emotions" (like joy and caution) experienced by those who are [[Wisdom|wise]], which come from correct appraisals of what is "good" and "bad."<ref> Arthur J. Pomeroy (ed.), ''Arius Didymus: Epitome of Stoic Ethics'' (Society of Biblical Literature, 1999, ISBN 978-1589836297).</ref> | ||

| − | + | [[Aristotle]] believed that emotions were an essential component of [[virtue]]. In the Aristotelian view all emotions (called passions) corresponded to appetites or capacities.<ref>Aristotle, Robert C. Bartlett and Susan D. Collins (trans.), ''Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics'' (University of Chicago Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0226026756).</ref> During the [[Middle Ages]], the Aristotelian view was adopted and further developed by [[scholasticism]], in particular by [[Thomas Aquinas]].<ref>Thomas Aquinas, ''Summa Theologica'' (Coyote Canyon Press, 2018, ISBN 978-1732190320).</ref> | |

| − | + | In Chinese antiquity, excessive emotion was believed to cause damage to ''[[qi]]'', which in turn, damages the vital organs.<ref> Yana Suchy, ''Clinical Neuropsychology of Emotion'' (The Guilford Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1609180720).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In the early eleventh century, [[Avicenna]], the [[Persia]]n physician, philosopher, and scientist, whose philosophical writings had a profound impact on [[Islamic philosophy]] and on medieval European scholasticism, theorized about the influence of emotions on [[health]] and [[behavior]]. He suggested the need to manage emotions.<ref>Amber Haque, "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists" ''Journal of Religion and Health'' 43(4) (2004):357–377.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | === Western theological approach=== | |

| + | The Christian perspective on emotion presupposes a theistic origin to humanity, created with the ability to feel and interact emotionally. This view understands human emotions as a basic part of Christian moral character. Though a somatic view would place the locus of emotions in the physical body, Christian theory of emotions would view the body more as a platform for the sensing and expression of emotions. Thus, emotions are understood as non-sensory perceptions that arise from personal caring and concern. Such emotions have the potential to be controlled through reasoned reflection. | ||

| − | + | The purpose in human life of emotions is understood to be for enjoyment and for people to benefit from them and use them to energize their behavior. In particular, six "fruit of the Holy Spirit" emotion-virtues are seen as foundational to the Christian life: contrition, joy, gratitude, hope, peace, and compassion.<ref>Robert C. Roberts, ''Spiritual Emotions: A Psychology of Christian Virtues'' (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2007, ISBN 978-0802827401).</ref> | |

| − | + | === Evolutionary theories === | |

| + | {{main|Evolution of emotion|Evolutionary psychology}} | ||

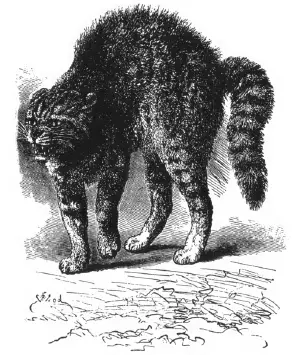

| + | [[File:Expression of the Emotions Figure 15.png|thumb|300px|Illustration from [[Charles Darwin]]'s ''[[The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals]]'' (1872)]] | ||

| − | + | From a mechanistic perspective, emotions can be regarded as positive or negative experiences associated with particular pattern of [[Physiology|physiological]] activity. Emotions produce different physiological, behavioral, and cognitive changes. The evolutionary perspective views the original role of emotions was to motivate adaptive behaviors that in the past would have contributed to the passing on of genes through survival, reproduction, and kin selection.<ref name=Schacter/> | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | Perspectives on emotions from evolutionary theory were initiated during the mid-late nineteenth century with [[Charles Darwin]]'s 1872 book ''[[The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals]]''.<ref>Charles Darwin, ''The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals'' (Penguin Classics, 2009 (original 1872), ISBN 0141439440).</ref> Darwin made several major contributions to the study of emotions: He treated the emotions as separate discrete entities, such as anger, fear, disgust, and so forth, an approach which was at variance with that of Wundt and others who viewed emotion as variations on a number of dimensions. Darwin pioneered various methods for studying non-verbal expressions, from which he concluded that some expressions had [[cross-cultural]] universality. <ref name=EkmanDarwin> Paul Ekman, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2781895/ Darwin's contributions to our understanding of emotional expressions] ''Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci.'' 364(1535) (2009): 3449–3451. Retrieved April 8, 2023.</ref> | |

| − | + | More recent research on social emotion focuses on evolutionary advantages of physical displays of emotion, including body language. For example, spite seems to work against the individual but it can establish an individual's reputation as someone to be feared. [[Shame]] and [[pride]] can motivate behaviors that help one maintain one's standing in a community, raising [[self-esteem]] and confidence in one's abilities to be successful.<ref name=Gaulin>Steven J. C. Gaulin and Donald H. McBurney, ''Evolutionary Psychology'' (Pearson, 2003, ISBN 978-0131115293).</ref> | |

| − | + | Darwin also detailed homologous expressions of emotions that occur in [[animal]]s, opening the way for research on emotions in animals and the eventual determination of the neural underpinnings of emotion.<ref name=EkmanDarwin/> Advances in [[neuroimaging]] allowed investigation into evolutionarily ancient parts of the brain, which has led to significant development of our understanding of the neurological bases of emotion.<ref name=LeDoux>Joseph E. LeDoux, ''The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life'' (Simon & Schuster, 1998, ISBN 978-0684836591)</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:Emotions - 3.png|thumb|350px|Examples of basic emotions]] | |

| + | [[File:Plutchik-wheel.png|350px|thumb|The emotion wheel]] | ||

| + | [[Paul Ekman]] developed Darwin's view that emotions are discrete, measurable, and physiologically distinct. His research showed that certain emotions appeared to be universally recognized, even in cultures that were preliterate and could not have learned associations for facial expressions through media. He also found that when people contorted their facial muscles into distinct facial expressions (for example, disgust), they reported subjective and physiological experiences that matched the distinct facial expressions. | ||

| − | [[ | + | Ekman's facial-expression research initially examined six basic emotions: [[anger]], [[disgust]], [[fear]], [[happiness]], [[sadness]], and [[surprise (emotion)|surprise]], although later he proposed that other universal emotions exist. [[Daniel Cordaro]] and [[Dacher Keltner]], both former students of Ekman, extended the list of universal emotions, adding [[amusement]], [[awe]], [[contentment]], [[desire]], [[embarrassment]], [[pain]], [[Relief (emotion)|relief]], and [[sympathy]] in both facial and vocal expressions. They also found evidence for [[boredom]], [[confusion]], [[interest (emotion)|interest]], [[pride]], and [[shame]] facial expressions, as well as [[contempt]], relief, and [[triumph]] vocal expressions.<ref>Dacher Keltner, Keith Oatley, and Jennifer M. Jenkins, ''Understanding Emotions'' (John Wiley & Sons, 2019, ISBN 978-1119657583).</ref> |

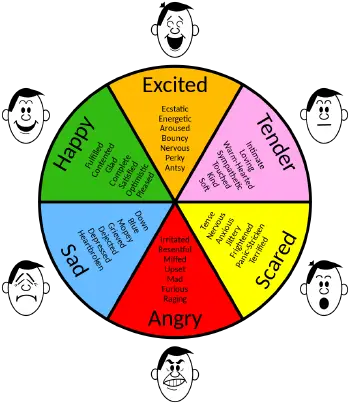

| − | + | [[Robert Plutchik]] agreed with Ekman's biologically driven perspective but developed a "wheel of emotions," suggesting eight primary emotions grouped on a positive or negative basis: joy versus sadness; anger versus fear; trust versus disgust; and surprise versus anticipation.<ref>Robert Plutchik, ''Emotions in the Practice of Psychotherapy: Clinical Implications of Affect Theories'' (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2000, ISBN 1557986940).</ref> He suggested that some basic emotions can be modified to form complex emotions, possibly in similar fashion to the way [[primary color]]s combine. Thus, ''primary emotions'' could blend to form the full spectrum of human emotional experience. For example, interpersonal [[anger]] and [[disgust]] could blend to form [[contempt]]. | |

| − | + | === Somatic theories === | |

| + | [[Somatic marker hypothesis|Somatic]] theories of emotion claim that bodily responses, rather than cognitive interpretations, are essential to emotions. The first modern version of such theories came from [[William James]] and Carl Lange working independently in the 1880s. Referred to as the James–Lange theory, this approach lost favor in the twentieth century, but regained popularity more recently due largely to theorists such as [[Joseph E. LeDoux]]<ref name=LeDoux/> and [[Robert Zajonc]]<ref>D.N. McIntosh, R.B. Zajonc, P.B. Vig, and S.W. Emerick, "Facial movement, breathing, temperature, and affect: Implications of the vascular theory of emotional efference" ''Cognition & Emotion'' 11(2) (1997):171–195.</ref> who appealed to neurological evidence. | ||

| − | + | ==== James–Lange theory ==== | |

| + | [[File:James-Lange Theory of Emotion.png|thumb|450px|Simplified graph of [[James–Lange theory|James-Lange Theory of Emotion]]]] | ||

| + | In his 1884 article [[William James]] argued that feelings and emotions were ''secondary'' to [[physiology|physiological]] phenomena.<ref>William James, [http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/James/emotion.htm What Is an Emotion?] ''Mind'' 9(34) (1884):188–205. Retrieved April 10, 2023.</ref> James proposed that the perception of what he called an "exciting fact" directly led to a physiological response, known as "emotion."<ref name=Carlson>Neil R. Carlson, ''Physiology of Behavior'' (Pearson, 2012, ISBN 0205239390).</ref> To account for different types of emotional experiences, James proposed that stimuli trigger activity in the [[autonomic nervous system]], which in turn produces an emotional experience in the brain. As James wrote, "the perception of bodily changes, as they occur, ''is'' the emotion." James further claimed that "we feel sad because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble, and either we cry, strike, or tremble because we are sorry, angry, or fearful, as the case may be."<ref name=James/> | ||

| − | + | An example of this theory in action would be as follows: An emotion-evoking stimulus ([[snake]]) triggers a pattern of physiological response (increased heart rate, faster breathing, etc.), which is interpreted as a particular emotion (fear). This theory is supported by experiments in which by manipulating the bodily state induces a desired emotional state.<ref name="Laird">James Laird, ''Feelings: the Perception of Self'' (Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0195098891).</ref> However, although physiological states have been shown to influence the emotional experience, there is no clear evidence to support causation, namely that bodily states actually cause the emotions. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Although mostly abandoned in its original form, Tim Dalgleish argued that most contemporary neuroscientists have embraced the components of the James-Lange theory of emotions: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>The James–Lange theory has remained influential. Its main contribution is the emphasis it places on the embodiment of emotions, especially the argument that changes in the bodily concomitants of emotions can alter their experienced intensity. Most contemporary neuroscientists would endorse a modified James–Lange view in which bodily feedback modulates the experience of emotion.<ref>Tim Dalgleish, "The emotional brain" ''Nature Reviews Neuroscience'' 5(7) (2004):582–589.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | ==== | + | ==== Cannon–Bard theory ==== |

| − | + | [[Walter Bradford Cannon]] agreed that physiological responses played a crucial role in emotions, but did not believe that physiological responses alone could explain [[subjectivity|subjective]] emotional experiences. He argued that physiological responses were too slow and often imperceptible and this could not account for the relatively rapid and intense subjective awareness of emotion, suggesting that emotion-evoking event triggers simultaneously both a physiological response and the conscious experience of an emotion.<ref name=Carlson/> | |

| − | + | Phillip Bard's work on animals further developed this theory. He found that sensory, motor, and physiological information all had to pass through the [[diencephalon]] (particularly the [[thalamus]]), before being subjected to any further processing. Therefore, Cannon also argued that it was not anatomically possible for sensory events to trigger a physiological response prior to triggering conscious awareness and emotional stimuli had to trigger both physiological and experiential aspects of emotion simultaneously.<ref> Walter B. Cannon, "Organization for Physiological Homeostasis" ''Physiological Reviews'' 9(3) (1929): 399–421.</ref> | |

| − | + | ==== Two-factor theory ==== | |

| + | The two-factor theory of emotion states that emotion is based on two factors: physiological arousal and cognitive label. This theory, developed by [[Stanley Schachter]] and [[Jerome E. Singer]], proposed that when an emotion is felt, a physiological arousal occurs and the person uses the immediate environment to search for emotional cues to label the physiological arousal. In other words, when the brain does not know why it feels an emotion it relies on external stimulation for cues on how to label it. | ||

| − | + | Schachter formulated this theory based on the earlier work of a Spanish physician, [[Gregorio Marañón]], who injected patients with [[adrenaline|epinephrine]] and subsequently asked them how they felt. Marañón found that most of these patients felt something but in the absence of an actual emotion-evoking stimulus, the patients were unable to interpret their physiological arousal as an experienced emotion. Schachter suggested that physiological reactions contributed to emotional experience by facilitating a focused cognitive appraisal of a given physiologically arousing event and that this appraisal was what defined the subjective emotional experience. Emotions were thus a result of two-stage process: general physiological arousal, and experience of emotion. For example, the physiological arousal, heart pounding, in a response to an evoking stimulus, the sight of a bear in the kitchen. The brain then quickly scans the area, to explain the pounding, and notices the bear. Consequently, the brain interprets the pounding heart as being the result of fearing the bear.<ref name=Schacter/> | |

=== Cognitive theories === | === Cognitive theories === | ||

| − | + | With the two-factor theory incorporating cognition, several theorists began to argue that cognitive activity in the form of judgments, evaluations, or thoughts were entirely necessary for an emotion to occur. For example [[Robert C. Solomon]] claimed that emotions are judgments. He has put forward a more nuanced view which responds to what he has called the 'standard objection' to cognitivism, the idea that a judgment that something is fearsome can occur with or without emotion, so judgment cannot be identified with emotion.<ref>Robert C. Solomon, ''True To Our Feelings'' (Oxford University Pres, 2001, ISBN 978-0195368536).</ref> The theory proposed by [[Nico Frijda]] where appraisal leads to action tendencies is another example.<ref name=Frijda/> | |

| − | + | [[Richard Lazarus]] proposed that the quality and intensity of emotions are controlled through cognitive processes. These processes underline coping strategies that form the emotional reaction by altering the relationship between the person and the environment. He argued that emotions must have some cognitive [[intentionality]], which may be conscious or unconscious.<ref name=Lazarus/> | |

| − | + | Lazarus' theory describes emotion as a disturbance that occurs in the following order: | |

| − | |||

| − | Lazarus' theory | ||

# Cognitive appraisal – The individual assesses the event cognitively, which cues the emotion. | # Cognitive appraisal – The individual assesses the event cognitively, which cues the emotion. | ||

# Physiological changes – The cognitive reaction starts biological changes such as increased heart rate or pituitary adrenal response. | # Physiological changes – The cognitive reaction starts biological changes such as increased heart rate or pituitary adrenal response. | ||

| Line 131: | Line 137: | ||

# Jenny screams and runs away. | # Jenny screams and runs away. | ||

| − | + | ===Other theories=== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

;Perceptual theory | ;Perceptual theory | ||

| − | + | A recent hybrid of the somatic and cognitive theories of emotion is the perceptual theory. This theory is neo-Jamesian in arguing that bodily responses are central to emotions, yet it emphasizes the meaningfulness of emotions, or the idea that emotions are about something, as is recognized by cognitive theories. The novel claim of this theory is that conceptually-based cognition is unnecessary for such meaning. Rather the bodily changes themselves ''perceive'' the meaningful content of the emotion through being causally triggered by certain situations. In this respect, emotions are held to be analogous to faculties such as vision or touch, which provide information about the relationship between the subject and the world in various ways.<ref name="Laird"/> | |

;Affective events theory | ;Affective events theory | ||

| − | [[Affective events theory]] is a communication-based theory developed by Howard M. Weiss and Russell Cropanzano | + | [[Affective events theory]] is a communication-based theory developed by Howard M. Weiss and Russell Cropanzano, that looks at the causes, structures, and consequences of emotional experience (especially in work contexts). This theory suggests that emotions are influenced and caused by events which in turn influence attitudes and behaviors. This theoretical frame also emphasizes ''time'' in that human beings experience what they call emotion episodes a "series of emotional states extended over time and organized around an underlying theme."<ref>Howard M. Weiss and Russell Cropanzano, "Affective Events Theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work" in B.M. Staw and L.L. Cummings (eds.), ''Research in Organizational Behaviour: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews: Vol 18'' (Elsevier, 1999, ISBN 978-1559389389).</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ;Situated perspective on emotion | |

| − | + | A situated perspective on emotion, developed by Paul E. Griffiths and Andrea Scarantino, emphasizes the importance of external factors in the development and communication of emotion, drawing upon the [[situationism (psychology)|situationism]] approach in psychology. This theory is markedly different from both cognitivist and neo-Jamesian theories of emotion, both of which see emotion as a purely internal process, with the environment only acting as a stimulus to the emotion. In contrast, a situationist perspective on emotion views emotion as the product of an organism investigating its environment, and observing the responses of other organisms. Emotion stimulates the evolution of social relationships, acting as a signal to mediate the behavior of other organisms. In some contexts, the expression of emotion (both voluntary and involuntary) could be seen as strategic moves in the transactions between different organisms. The situated perspective on emotion states that conceptual thought is not an inherent part of emotion, since emotion is an action-oriented form of skillful engagement with the world. Griffiths and Scarantino suggested that this perspective on emotion could be helpful in understanding [[phobia]]s, as well as the emotions of infants and animals.<ref>Paul Griffiths and Andrea Scarantino, "Emotions in the Wild: The Situated Perspective on Emotion" in Philip Robbins and Murat Aydede (eds.), ''The Cambridge Handbook of Situated Cognition'' (Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0521848329).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | A situated perspective on emotion, developed by Paul E. Griffiths and Andrea Scarantino, emphasizes the importance of external factors in the development and communication of emotion, drawing upon the [[situationism (psychology)|situationism]] approach in psychology. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Studying emotions == | == Studying emotions == | ||

| − | Emotions involve different components, such as subjective experience, [[cognition|cognitive process]]es, expressive behavior, psychophysiological changes, and instrumental behavior. At one time, academics attempted to identify | + | Emotions involve different components, such as subjective experience, [[cognition|cognitive process]]es, expressive behavior, psychophysiological changes, and instrumental behavior. At one time, academics attempted to identify emotions with one of the components: [[William James]] with a subjective experience, [[behaviorism|behaviorist]]s with instrumental behavior, [[psychophysiology|psychophysiologist]]s with physiological changes, and so on. More recently, emotion is understood to involve multiple components. The different components of emotion are categorized somewhat differently depending on the academic discipline. In [[psychology]] and [[philosophy]], for example, emotion typically includes a [[subjectivity|subjective]], [[consciousness|conscious]] [[qualia|experience]] characterized primarily by [[psychophysiology|psychophysiological]] [[emotional expression|expression]]s, [[metabolism|biological reaction]]s, and [[mental state]]s. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Research on emotion has increased over the past two decades with many fields contributing including [[psychology]], [[medicine]], [[history]], [[sociology]], and [[computer science]], using different approaches and techniques. In [[psychiatry]], emotions are examined as part of the discipline's study and treatment of [[mental disorder]]s in humans. [[Nursing]] studies emotions as part of its approach to the provision of holistic health care. [[Psychology]] examines emotions from a scientific perspective by treating them as mental processes and behavior and they explore the underlying physiological and neurological processes. The neural mechanisms of emotion are studied by combining [[neuroscience]] with the psychological study of [[personality]], emotion, and mood. In [[education]], the role of emotions in relation to learning is examined. | |

| − | + | In [[sociology]], emotions are examined for the role they play in human society, social patterns and interactions, and culture. In [[anthropology]], scholars use [[ethnography]] to undertake contextual analyses and cross-cultural comparisons of a range of human activities. In [[communication studies]], scholars study the role that emotion plays in the dissemination of ideas and messages as well as the role of emotions in organizations, from the perspectives of managers, employees, and even customers. | |

| − | In [[economics]] | + | In [[economics]], emotions are analyzed in some sub-fields of [[microeconomics]], in order to assess the role of emotions on purchase decision-making and risk perception. In [[criminology]], emotions are examined in relation to studies of "toughness," aggressive behavior, and hooliganism. In [[law]], evidence about people's emotions is often raised in [[tort]] law claims for compensation and in [[criminal law]] prosecutions against alleged lawbreakers (as evidence of the defendant's state of mind during trials, sentencing, and [[parole]] hearings). In [[political science]], emotions are examined in a number of sub-fields, such as the analysis of voter decision-making. |

| − | In [[philosophy]], emotions are studied in sub-fields such as [[ethics]], the [[aesthetics|philosophy of art]] (for example, sensory–emotional values, and matters of [[taste (sociology)|taste]] and [[sentimentality]]), and the [[philosophy of music]] | + | In [[philosophy]], emotions are studied in sub-fields such as [[ethics]], the [[aesthetics|philosophy of art]] (for example, sensory–emotional values, and matters of [[taste (sociology)|taste]] and [[sentimentality]]), and the [[philosophy of music]]. In [[history]], speculation on the emotional state of the authors of historical documents is one of the tools of interpretation. In [[literature]] and film-making, the expression of emotion is the cornerstone of genres such as drama, melodrama, and romance. Emotion is also studied in non-human animals. |

=== Sociology === | === Sociology === | ||

| − | + | Sociological attention to emotion has varied over time. | |

| − | + | Charles Horton Cooley regarded pride and shame as the most important emotions that drive people to take various social actions. During every encounter, he proposed that we monitor ourselves through the "looking glass" that the gestures and reactions of others provide. Depending on these reactions, we either experience pride or shame and this results in particular paths of action.<ref> Charles Horton Cooley, ''Human Nature and the Social Order'' (Andesite Press, 2017 (original 1902), ISBN 1375906550).</ref> | |

| − | + | [[Émile Durkheim]] wrote about the collective effervescence or emotional energy that was experienced by members of [[totem]]ic rituals in [[Australian Aborigine|Australian Aboriginal society]]. He explained how the heightened state of emotional energy achieved during totemic rituals transported individuals above themselves giving them the sense that they were in the presence of a higher power, a force, that was embedded in the sacred objects that were worshiped. These feelings of exaltation, he argued, ultimately lead people to believe that there were forces that governed sacred objects.<ref> Emile Durkheim, Joseph Ward Swain (trans.), ''The Elementary Forms of Religious Life'' (Benediction Classics, 2016 (original 1912), ISBN 978-1781396971).</ref> | |

| − | + | Jonathan Turner analyzed a wide range of emotion theories across different fields of research including sociology, psychology, evolutionary science, and neuroscience. Based on his analysis, he identified four primary emotions: assertive-anger, aversion-fear, satisfaction-happiness, and disappointment-sadness. These four categories are combined to produce more elaborate and complex emotional experiences, including sentiments such as pride, triumph, and awe. Emotions can also be experienced at different levels of intensity.<ref>Jonathan H. Turner, ''Human Emotions: A Sociological Theory'' (Routledge, 2007, ISBN 978-0415427821).</ref> | |

| − | + | ===Psychology=== | |

| + | Ethnographic and cross-cultural studies of emotions have shown the variety of ways in which emotions differ with cultures. Because of these differences, many cross-cultural psychologists and anthropologists challenge the idea of universal classifications of emotions altogether. However, others argue that there are some universal bases of emotions.<ref name=Wierzbicka>Anna Wierzbicka, ''Emotions across Languages and Cultures: Diversity and Universals'' (Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0521590426).</ref> | ||

| − | + | The largest piece of evidence that disputes the universality of emotions is [[language]]. Differences within languages directly correlate to differences in emotion taxonomy. Languages differ in that they categorize emotions based on different components. Some may categorize by event types whereas others categorize by action readiness. Furthermore, emotion taxonomies vary due to the differing implications emotions have in different languages. That being said, not all English words have equivalents in all other languages and vice versa, indicating that there are words for emotions present in some languages but not in others.<ref name=Wierzbicka/> For example, ''[[schadenfreude]]'' in German and ''[[saudade]]'' in Portuguese are commonly expressed in emotions in their respective languages, but lack an English equivalent. | |

| − | + | === Neurobiology === | |

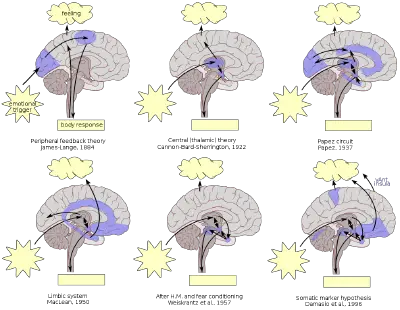

| + | [[File:Timeline of brain models of emotion.png|thumb|400px|Timeline of some of the most prominent brain models of emotion in [[affective neuroscience]]]] | ||

| − | + | Based on discoveries made through neural mapping of the [[limbic system]], the [[neuroscience|neurobiological]] explanation of human emotion is that emotion is a pleasant or unpleasant mental state organized in the limbic system of the mammalian [[brain]]. If distinguished from reactive responses of [[reptile]]s, emotions would then be mammalian elaborations of general [[vertebrate]] arousal patterns, in which [[neurochemical]]s (for example, [[dopamine]], [[norepinephrine|noradrenaline]], and [[serotonin]]) step-up or step-down the brain's activity level, as visible in body movements, gestures, and postures. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Emotions are thought to be related to certain activities in brain areas that direct our attention, motivate our behavior, and determine the significance of what is going on around us. Pioneering work by [[Paul Broca]] and others suggested that emotion is related to a group of structures in the center of the brain called the [[limbic system]], which includes the [[hypothalamus]], [[cingulate cortex]], [[hippocampus|hippocampi]], and other structures. More recent research has shown that some of these [[limbic system|limbic structure]]s are not as directly related to emotion as others are while some non-limbic structures have been found to be of greater emotional relevance. | |

| − | + | For example, the emotion of [[love]] is proposed to be the expression of Paleocircuits of the mammalian brain (specifically, modules of the [[cingulate cortex]] (or gyrus)) which facilitate the care, feeding, and grooming of offspring. Other emotions like fear and anxiety long thought to be exclusively generated by the most primitive parts of the brain (stem) and more associated to the fight-or-flight responses of behavior, have also been associated as adaptive expressions of defensive behavior whenever a threat is encountered. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Another neurological approach proposed by [[Arthur Craig|Bud Craig]] in 2003 distinguishes two classes of emotion: "classical" emotions such as love, anger and fear that are evoked by environmental stimuli, and "[[homeostatic emotion]]s" – attention-demanding feelings evoked by body states, such as pain, hunger and fatigue, that motivate behavior (withdrawal, eating or resting in these examples) aimed at maintaining the body's internal milieu at its ideal state. [[Derek Denton]] calls the latter "primordial emotions" and defines them as: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>[T]he subjective element of the instincts, which are the genetically programmed behavior patterns which contrive homeostasis. They include thirst, hunger for air, hunger for food, pain and hunger for specific minerals etc. There are two constituents of a primordial emotion – the specific sensation which when severe may be imperious, and the compelling intention for gratification by a consummatory act."<ref>Derek Denton, ''The Primordial Emotions: The Dawning of Consciousness'' (Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0199203147).</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=== Computer science === | === Computer science === | ||

| − | + | In the twenty-first century, research in computer science, engineering, psychology, and neuroscience has been aimed at developing devices that recognize human [[affect (psychology)|affect]] display and model emotions. [[Affective computing]] deals with the design of systems and devices that can recognize, interpret, and process human emotions. Detecting emotional information begins with passive [[sensor]]s which capture data about the user's physical state or behavior without interpreting the input. The data gathered is analogous to the cues humans use to perceive emotions in others.<ref>Michael A. Arbib and James J. Bonaiuto (eds.), ''From Neuron to Cognition via Computational Neuroscience'' (The MIT Press, 2016, ISBN 978-0262034968).</ref> | |

| − | In the | ||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| − | == | + | == References == |

| − | + | * Aquinas, Thomas. ''Summa Theologica''.Coyote Canyon Press, 2018. ISBN 978-1732190320 | |

| − | * | + | * Arbib, Michael A., and James J. Bonaiuto (eds.). ''From Neuron to Cognition via Computational Neuroscience''. The MIT Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0262034968 |

| − | * | + | * Aristotle, Robert C. Bartlett and Susan D. Collins (trans.). ''Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics''. University of Chicago Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0226026756 |

| − | * | + | * Barrett, Lisa Feldman, and James A. Russell (eds.), ''The Psychological Construction of Emotion''. The Guilford Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1462516971 |

| − | * | + | * Barrett, Lisa Feldman, Michael Lewis, and Jeannette M. Haviland-Jones (eds.). ''Handbook of Emotions''. The Guilford Press, 2016. ISBN 978-1462525348 |

| − | * | + | * Carlson, Neil R. ''Physiology of Behavior''. Pearson, 2012. ISBN 0205239390 |

| − | * | + | * Cooley, Charles Horton. ''Human Nature and the Social Order''. Andesite Press, 2017 (original 1902). ISBN 1375906550 |

| − | * | + | * Dalgleish, Tim, and Mick Power (eds.). ''Handbook of Cognition and Emotion''. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1999. ISBN 978-0471978367 |

| − | * | + | * Darwin, Charles. ''The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals''. Penguin Classics, 2009 (original 1872). ISBN 0141439440 |

| − | * | + | * Denton, Derek. ''The Primordial Emotions: The Dawning of Consciousness''. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0199203147 |

| − | * | + | * Descartes, Rene, Stephen Voss (trans.). ''The Passions of the Soul''. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1989 (original 1649). ISBN 978-0872200357 |

| − | * LeDoux, | + | * Dixon, Thomas. ''From Passions to Emotions: The Creation of a Secular Psychological Category''. Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0521026695 |

| − | * Mandler, | + | * Durkheim, Emile. Joseph Ward Swain (trans.). ''The Elementary Forms of Religious Life'' Benediction Classics, 2016 (original 1912). ISBN 978-1781396971 |

| − | * | + | * Ekman, Paul, and Richard J. Davidson (eds.). T''he Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions''. Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0195089448 |

| − | * | + | * Fox, Elaine. ''Emotion Science: Cognitive and Neuroscientific Approaches to Understanding Human Emotions''. Red Globe Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0230005181 |

| − | * Roberts, Robert. ( | + | * Frijda, Nico H. ''The Emotions''. Cambridge University Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0521316002 |

| − | * Solomon, | + | * Gaulin, Steven J. C., and Donald H. McBurney. ''Evolutionary Psychology''. Pearson, 2003. ISBN 978-0131115293 |

| − | * | + | * Hume, David. ''A Treatise of Human Nature''. Penguin Classics, 1986 (original 1739–1740). ISBN 978-0140432442 |

| + | * James, William. ''The Principles of Psychology''. Harvard University Press, 1983 (original 1890). ISBN 978-0674706255 | ||

| + | * Kagan, Jerome. ''What is Emotion?: History, measures, and meanings''. Yale University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0300143096 | ||

| + | * Keltner, Dacher, Keith Oatley, and Jennifer M. Jenkins. ''Understanding Emotions''. John Wiley & Sons, 2019. ISBN 978-1119657583 | ||

| + | * Laird, James. ''Feelings: the Perception of Self''. Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0195098891 | ||

| + | * Lazarus, Richard S., and Bernice N. Lazarus. ''Passion and Reason: Making Sense of Our Emotions''. Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0195104615 | ||

| + | * LeDoux, Joseph E. ''The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life''. Simon & Schuster, 1998. ISBN 978-0684836591 | ||

| + | * Mandler, George. ''Mind and Emotion''. Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company, 1975. ISBN 978-0898743500 | ||

| + | * Mandler, George. ''Mind and Body: Psychology of Emotion and Stress''. W W Norton & Co Inc, 1984. ISBN 978-0393953466 | ||

| + | * Panksepp, Jaak. ''Affective Neuroscience: The foundations of human and animal emotions''. Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0195178050 | ||

| + | * Parrott,W. Gerrod (ed.). ''The Positive Side of Negative Emotions''. The Guilford Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1462513338 | ||

| + | * Plutchik, Robert. ''Emotions in the Practice of Psychotherapy: Clinical Implications of Affect Theories''. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2000. ISBN 1557986940 | ||

| + | * Pomeroy, Arthur J. (ed.). ''Arius Didymus: Epitome of Stoic Ethics''. Society of Biblical Literature, 1999. ISBN 978-1589836297 | ||

| + | * Robbins, Philip, and Murat Aydede (eds.). ''The Cambridge Handbook of Situated Cognition''. Cambridge University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0521848329 | ||

| + | * Roberts, Robert C. ''Spiritual Emotions: A Psychology of Christian Virtues''. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2007. ISBN 978-0802827401 | ||

| + | * Staw, B.M., and L.L. Cummings (eds.). ''Research in Organizational Behaviour: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews: Vol 18''. Elsevier, 1999. ISBN 978-1559389389 | ||

| + | * Smith, Tiffany Watt. ''The Book of Human Emotions''. Little, Brown Spark, 2016. ISBN 978-0316265409 | ||

| + | * Solomon, Robert C. ''The Passions: Emotions and the Meaning of Life''. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1993. ISBN 978-0872202269 | ||

| + | * Solomon, Robert C. ''True To Our Feelings''. Oxford University Pres, 2001. ISBN 978-0195368536 | ||

| + | * Turner, Jonathan H. ''Human Emotions: A Sociological Theory''. Routledge, 2007. ISBN 978-0415427821 | ||

| + | * Wierzbicka, Anna. ''Emotions across Languages and Cultures: Diversity and Universals''. Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0521590426 | ||

| + | * Wundt, Willhelm M. ''Outlines of Psychology''. Cornell University Library, 2009 (original 1897). ISBN 1112410600 | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | All links retrieved | + | All links retrieved February 13, 2024. |

* [https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/emotion/ Emotion] ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' | * [https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/emotion/ Emotion] ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' | ||

| Line 260: | Line 238: | ||

* [https://www.verywellmind.com/what-are-emotions-2795178 Emotions and Types of Emotional Responses] ''Very Well Mind'' | * [https://www.verywellmind.com/what-are-emotions-2795178 Emotions and Types of Emotional Responses] ''Very Well Mind'' | ||

* [https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hvcc-psychology-1/chapter/introduction-to-emotion/ Emotion] ''Lumen Learning: Introduction to Psychology'' | * [https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hvcc-psychology-1/chapter/introduction-to-emotion/ Emotion] ''Lumen Learning: Introduction to Psychology'' | ||

| + | * [https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/emotion-Christian-tradition/ Emotions in the Christian Tradition] ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' | ||

[[Category:Psychology]] | [[Category:Psychology]] | ||

| Line 265: | Line 244: | ||

[[Category:Philosophy]] | [[Category:Philosophy]] | ||

| − | {{Credit|Emotion|1127002172}} | + | {{Credit|Emotion|1127002172|Emotion_classification|1145771560}} |

Latest revision as of 18:27, 13 February 2024

Emotions are mental states brought on by neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure. Emotions are often intertwined with the mood, temperament, personality, disposition, or creativity of the individual experiencing the emotion.

Emotions are complex, involving different components, such as subjective experience, cognitive processes, expressive behavior, psychophysiological changes, and instrumental behavior. At one time, academics attempted to identify the emotion with one of the components: William James with a subjective experience, behaviorists with instrumental behavior, psychophysiologists with physiological changes, and so on. More recently, emotion is said to consist of all the components.

Research on emotion currently involves many fields, including psychology, medicine, history, sociology, and computer science. This reflects the fact that emotions are not only complex in themselves but are also one aspect of the complexity of human nature.

Etymology

The word "emotion" dates back to the 1570s, when it was adapted from the French word émouvoir, which means "to stir up," which derives from the Latin emovere "move out, remove, agitate," from ex "out" plus movere "to move." The term was first recorded to refer to "strong feeling" in the 1650s; and was extended to any feeling by 1808.[1]

Definitions

The Merriam-Webster definition of emotion is "a conscious mental reaction (such as anger or fear) subjectively experienced as strong feeling usually directed toward a specific object and typically accompanied by physiological and behavioral changes in the body."[2]

This modern concept of emotion first emerged in the English language in the nineteenth century:

No one felt emotions before about 1830. Instead they felt other things – 'passions', 'accidents of the soul', 'moral sentiments' – and explained them very differently from how we understand emotions today.[3]

"Emotion" was introduced into academic discussion as a catch-all term to passions, sentiments, and affections.[4]

They are generally understood to be mental states brought on by neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure.[5][6][7]

There is currently no scientific consensus on a definition of emotion.[8] In general, emotions are evoked in response to significant internal and external events.[7]

Thus, emotions have been described as consisting of a coordinated set of responses, which may include verbal, physiological, behavioral, and neural mechanisms.[9]

Emotion can be differentiated from a number of similar constructs within the field of affective neuroscience[9]:

- Feeling: not all feelings include emotion, such as the feeling of knowing. In the context of emotion, feelings are best understood as a subjective representation of emotions, private to the individual experiencing them.

- Moods: diffuse affective states that generally last for much longer durations than emotions; they are also usually less intense than emotions and often appear to lack a contextual stimulus.

- Affect: used to describe the underlying affective experience of an emotion or a mood.

History

Human nature and the accompanying bodily sensations have always been part of the interests of thinkers and philosophers, in both Western and Eastern societies. Emotional states have been associated with the divine and with the enlightenment of the human mind and body.[10] The ever-changing actions of individuals and their mood variations were of great importance to most Western philosophers, including Aristotle, Plato, Descartes, Aquinas, Machiavelli, Spinoza, and Hobbes, leading them to propose extensive theories—often competing theories—that sought to explain emotion and the accompanying motivators of human action, as well as its consequences. For example, Descartes defined and investigates the six primary passions (wonder, love, hate, desire, joy, and sadness) in his philosophical treatise, The Passions of the Soul.[11]

In the Age of Enlightenment, Scottish thinker David Hume proposed a revolutionary argument that sought to explain the main motivators of human action and conduct. He proposed that actions are motivated by "fears, desires, and passions." As he wrote in his book Treatise of Human Nature (1739–1740):

Reason alone can never be a motive to any action of the will… it can never oppose passion in the direction of the will… The reason is, and ought to be, the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them."[12]

Hume attempted to explain that reason and further action would be subject to the desires and experience of the self. Later thinkers would propose that actions and emotions are deeply interrelated with social, political, historical, and cultural aspects of reality that would also come to be associated with sophisticated neurological and physiological research on the brain and other parts of the physical body.

In the nineteenth century, emotions were considered adaptive and were studied from an empiricist perspective. In the late nineteenth century, the most influential theorists were William James (1842–1910) and Carl Lange (1834–1900). James was an American psychologist and philosopher. In his Principles of Psychology (1890) he proposed that emotions are the sensation of changes in the body: “the bodily changes follow directly the perception of the exciting fact, and that our feeling of the same changes as they occur IS the emotion.”[13] His position was that the physiological changes come first and without them, there can be no feeling of emotion, and all that would remain “would be purely cognitive in form, pale, colorless, destitute of emotional warmth.”[13]

Lange was a Danish physician and psychologist. Working independently, they developed a hypothesis on the origin and nature of emotions, referred to as the James–Lange theory. This states that within human beings, as a response to experiences in the world, the autonomic nervous system creates physiological events such as muscular tension, a rise in heart rate, perspiration, and dryness of the mouth. Emotions, then, are feelings which come about as a result of these physiological changes, rather than being their cause.[14]

The twentieth century saw many advances in the study of emotions. For example, Richard Lazarus (1922–2002) specialized in studies of emotion and stress, especially in relation to cognition; Herbert A. Simon (1916–2001), included emotions in decision making and artificial intelligence; Robert Plutchik (1928–2006) developed a psychoevolutionary theory of emotion; Robert C. Solomon (1942–2007) contributed to the theories on the philosophy of emotions;[15] Nico Frijda (1927–2015) advanced the theory that human emotions serve to promote a tendency to undertake actions that are appropriate in the circumstances;[16] and Jaak Panksepp (1943–2017) pioneered studies in affective neuroscience.

Classification

Human beings experience emotion which influence actions, thoughts, and behavior. Both positive and negative emotions are needed in our daily lives.[17] A number of models have been proposed to classify emotions.

For both theoretical and practical reasons researchers often define emotions according to one or more dimensions. Dimensional models of emotion attempt to conceptualize human emotions by defining where they lie in two or three dimensions. They often incorporate valence (good (positive) versus bad (negative) valence) and arousal or intensity dimensions. Several dimensional models have been proposed.

For example, Wilhelm Max Wundt proposed in 1897 that emotions can be described by three dimensions: "pleasurable versus unpleasurable," "arousing or subduing," and "strain or relaxation."[18]

Another approach has been to focus on specifying basic emotions, or categories of emotion which are independent, and then adding the dimensions as modifiers.

Several models of the "basic emotions" have been suggested:

- William James in 1890 proposed four basic emotions: fear, grief, love, and rage, based on bodily involvement.[13]

- Paul Ekman identified six basic emotions: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise, which can be linked to facial expressions.[19] He later expanded this list of basic emotions, including a range of positive and negative emotions that are not all encoded in facial muscles. The newly included emotions are: Amusement, Contempt, Contentment, Embarrassment, Excitement, Guilt, Pride in achievement, Relief, Satisfaction, Sensory pleasure, and Shame.[20]

- Richard and Bernice Lazarus in 1996 expanded Ekman's original list to 15 emotions: aesthetic experience, anger, anxiety, compassion, depression, envy, fright, gratitude, guilt, happiness, hope, jealousy, love, pride, relief, sadness, and shame.[21]

- Alan S. Cowen and Dacher Keltner, using statistical methods to analyze emotional states elicited by short videos, identified 27 varieties of emotional experience: admiration, adoration, aesthetic appreciation, amusement, anger, anxiety, awe, awkwardness, boredom, calmness, confusion, craving, disgust, empathic pain, entrancement, excitement, fear, horror, interest, joy, nostalgia, relief, romance, sadness, satisfaction, sexual desire and surprise.[22]

Theories

Emotions are complex. There are various theories on the question of whether or not emotions cause changes in our behavior.[7] The physiology of emotion is closely linked to arousal of the nervous system. Emotion is often the driving force behind motivation.[23] On the other hand, emotions are not causal forces but simply syndromes of components, which might include motivation, feeling, behavior, and physiological changes, but none of these components is the emotion. Nor is the emotion an entity that causes these components.[24] George Mandler provides an extensive theoretical and empirical discussion of emotion as influenced by cognition, consciousness, and the autonomic nervous system.[25][26]

Early theories

In Stoic theories, normal emotions (like delight and fear) are described as irrational impulses which come from incorrect appraisals of what is "good" or "bad." Alternatively, there are "good emotions" (like joy and caution) experienced by those who are wise, which come from correct appraisals of what is "good" and "bad."[27]

Aristotle believed that emotions were an essential component of virtue. In the Aristotelian view all emotions (called passions) corresponded to appetites or capacities.[28] During the Middle Ages, the Aristotelian view was adopted and further developed by scholasticism, in particular by Thomas Aquinas.[29]

In Chinese antiquity, excessive emotion was believed to cause damage to qi, which in turn, damages the vital organs.[30]

In the early eleventh century, Avicenna, the Persian physician, philosopher, and scientist, whose philosophical writings had a profound impact on Islamic philosophy and on medieval European scholasticism, theorized about the influence of emotions on health and behavior. He suggested the need to manage emotions.[31]

Western theological approach

The Christian perspective on emotion presupposes a theistic origin to humanity, created with the ability to feel and interact emotionally. This view understands human emotions as a basic part of Christian moral character. Though a somatic view would place the locus of emotions in the physical body, Christian theory of emotions would view the body more as a platform for the sensing and expression of emotions. Thus, emotions are understood as non-sensory perceptions that arise from personal caring and concern. Such emotions have the potential to be controlled through reasoned reflection.

The purpose in human life of emotions is understood to be for enjoyment and for people to benefit from them and use them to energize their behavior. In particular, six "fruit of the Holy Spirit" emotion-virtues are seen as foundational to the Christian life: contrition, joy, gratitude, hope, peace, and compassion.[32]

Evolutionary theories

From a mechanistic perspective, emotions can be regarded as positive or negative experiences associated with particular pattern of physiological activity. Emotions produce different physiological, behavioral, and cognitive changes. The evolutionary perspective views the original role of emotions was to motivate adaptive behaviors that in the past would have contributed to the passing on of genes through survival, reproduction, and kin selection.[7]

Perspectives on emotions from evolutionary theory were initiated during the mid-late nineteenth century with Charles Darwin's 1872 book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.[33] Darwin made several major contributions to the study of emotions: He treated the emotions as separate discrete entities, such as anger, fear, disgust, and so forth, an approach which was at variance with that of Wundt and others who viewed emotion as variations on a number of dimensions. Darwin pioneered various methods for studying non-verbal expressions, from which he concluded that some expressions had cross-cultural universality. [34]

More recent research on social emotion focuses on evolutionary advantages of physical displays of emotion, including body language. For example, spite seems to work against the individual but it can establish an individual's reputation as someone to be feared. Shame and pride can motivate behaviors that help one maintain one's standing in a community, raising self-esteem and confidence in one's abilities to be successful.[23]

Darwin also detailed homologous expressions of emotions that occur in animals, opening the way for research on emotions in animals and the eventual determination of the neural underpinnings of emotion.[34] Advances in neuroimaging allowed investigation into evolutionarily ancient parts of the brain, which has led to significant development of our understanding of the neurological bases of emotion.[35]

Paul Ekman developed Darwin's view that emotions are discrete, measurable, and physiologically distinct. His research showed that certain emotions appeared to be universally recognized, even in cultures that were preliterate and could not have learned associations for facial expressions through media. He also found that when people contorted their facial muscles into distinct facial expressions (for example, disgust), they reported subjective and physiological experiences that matched the distinct facial expressions.

Ekman's facial-expression research initially examined six basic emotions: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise, although later he proposed that other universal emotions exist. Daniel Cordaro and Dacher Keltner, both former students of Ekman, extended the list of universal emotions, adding amusement, awe, contentment, desire, embarrassment, pain, relief, and sympathy in both facial and vocal expressions. They also found evidence for boredom, confusion, interest, pride, and shame facial expressions, as well as contempt, relief, and triumph vocal expressions.[36]

Robert Plutchik agreed with Ekman's biologically driven perspective but developed a "wheel of emotions," suggesting eight primary emotions grouped on a positive or negative basis: joy versus sadness; anger versus fear; trust versus disgust; and surprise versus anticipation.[37] He suggested that some basic emotions can be modified to form complex emotions, possibly in similar fashion to the way primary colors combine. Thus, primary emotions could blend to form the full spectrum of human emotional experience. For example, interpersonal anger and disgust could blend to form contempt.

Somatic theories

Somatic theories of emotion claim that bodily responses, rather than cognitive interpretations, are essential to emotions. The first modern version of such theories came from William James and Carl Lange working independently in the 1880s. Referred to as the James–Lange theory, this approach lost favor in the twentieth century, but regained popularity more recently due largely to theorists such as Joseph E. LeDoux[35] and Robert Zajonc[38] who appealed to neurological evidence.

James–Lange theory

In his 1884 article William James argued that feelings and emotions were secondary to physiological phenomena.[39] James proposed that the perception of what he called an "exciting fact" directly led to a physiological response, known as "emotion."[40] To account for different types of emotional experiences, James proposed that stimuli trigger activity in the autonomic nervous system, which in turn produces an emotional experience in the brain. As James wrote, "the perception of bodily changes, as they occur, is the emotion." James further claimed that "we feel sad because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble, and either we cry, strike, or tremble because we are sorry, angry, or fearful, as the case may be."[13]

An example of this theory in action would be as follows: An emotion-evoking stimulus (snake) triggers a pattern of physiological response (increased heart rate, faster breathing, etc.), which is interpreted as a particular emotion (fear). This theory is supported by experiments in which by manipulating the bodily state induces a desired emotional state.[41] However, although physiological states have been shown to influence the emotional experience, there is no clear evidence to support causation, namely that bodily states actually cause the emotions.

Although mostly abandoned in its original form, Tim Dalgleish argued that most contemporary neuroscientists have embraced the components of the James-Lange theory of emotions:

The James–Lange theory has remained influential. Its main contribution is the emphasis it places on the embodiment of emotions, especially the argument that changes in the bodily concomitants of emotions can alter their experienced intensity. Most contemporary neuroscientists would endorse a modified James–Lange view in which bodily feedback modulates the experience of emotion.[42]

Cannon–Bard theory

Walter Bradford Cannon agreed that physiological responses played a crucial role in emotions, but did not believe that physiological responses alone could explain subjective emotional experiences. He argued that physiological responses were too slow and often imperceptible and this could not account for the relatively rapid and intense subjective awareness of emotion, suggesting that emotion-evoking event triggers simultaneously both a physiological response and the conscious experience of an emotion.[40]

Phillip Bard's work on animals further developed this theory. He found that sensory, motor, and physiological information all had to pass through the diencephalon (particularly the thalamus), before being subjected to any further processing. Therefore, Cannon also argued that it was not anatomically possible for sensory events to trigger a physiological response prior to triggering conscious awareness and emotional stimuli had to trigger both physiological and experiential aspects of emotion simultaneously.[43]

Two-factor theory

The two-factor theory of emotion states that emotion is based on two factors: physiological arousal and cognitive label. This theory, developed by Stanley Schachter and Jerome E. Singer, proposed that when an emotion is felt, a physiological arousal occurs and the person uses the immediate environment to search for emotional cues to label the physiological arousal. In other words, when the brain does not know why it feels an emotion it relies on external stimulation for cues on how to label it.

Schachter formulated this theory based on the earlier work of a Spanish physician, Gregorio Marañón, who injected patients with epinephrine and subsequently asked them how they felt. Marañón found that most of these patients felt something but in the absence of an actual emotion-evoking stimulus, the patients were unable to interpret their physiological arousal as an experienced emotion. Schachter suggested that physiological reactions contributed to emotional experience by facilitating a focused cognitive appraisal of a given physiologically arousing event and that this appraisal was what defined the subjective emotional experience. Emotions were thus a result of two-stage process: general physiological arousal, and experience of emotion. For example, the physiological arousal, heart pounding, in a response to an evoking stimulus, the sight of a bear in the kitchen. The brain then quickly scans the area, to explain the pounding, and notices the bear. Consequently, the brain interprets the pounding heart as being the result of fearing the bear.[7]

Cognitive theories

With the two-factor theory incorporating cognition, several theorists began to argue that cognitive activity in the form of judgments, evaluations, or thoughts were entirely necessary for an emotion to occur. For example Robert C. Solomon claimed that emotions are judgments. He has put forward a more nuanced view which responds to what he has called the 'standard objection' to cognitivism, the idea that a judgment that something is fearsome can occur with or without emotion, so judgment cannot be identified with emotion.[44] The theory proposed by Nico Frijda where appraisal leads to action tendencies is another example.[16]

Richard Lazarus proposed that the quality and intensity of emotions are controlled through cognitive processes. These processes underline coping strategies that form the emotional reaction by altering the relationship between the person and the environment. He argued that emotions must have some cognitive intentionality, which may be conscious or unconscious.[21]

Lazarus' theory describes emotion as a disturbance that occurs in the following order:

- Cognitive appraisal – The individual assesses the event cognitively, which cues the emotion.

- Physiological changes – The cognitive reaction starts biological changes such as increased heart rate or pituitary adrenal response.