Wiesel, Elie

Mary Anglin (talk | contribs) m (→Books) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (70 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{copyedited}}{{2Copyedited}} |

| + | {{epname|Wiesel, Elie}} | ||

{{Infobox Writer | {{Infobox Writer | ||

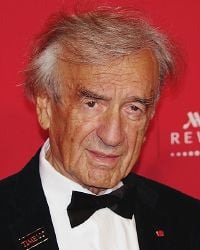

| name = Elie Wiesel | | name = Elie Wiesel | ||

| − | | image = | + | | image = Elie Wiesel 2012 Shankbone.JPG |

| caption = | | caption = | ||

| − | | birth_date = | + | | birth_date = {{Birth date|1928|09|30}} |

| birth_place = [[Sighetu Marmaţiei|Sighet]], [[Maramureş County]], [[Romania]] | | birth_place = [[Sighetu Marmaţiei|Sighet]], [[Maramureş County]], [[Romania]] | ||

| − | | death_date = | + | | death_date = {{Death date and age|2016|07|02|1928|09|30}} |

| − | | death_place = | + | | death_place = New York City |

| occupation = political activist, professor | | occupation = political activist, professor | ||

| genre = | | genre = | ||

| Line 17: | Line 18: | ||

| footnotes = | | footnotes = | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Wiesel was | + | '''Eliezer Wiesel''' (commonly known as '''Elie''') (September 30, 1928 - July 2, 2016) was a world-renowned [[Hungary|Hungarian]] [[Romania|Romanian]] [[Jew|Jewish]] novelist, [[philosophy|philosopher]], humanitarian, political activist, and [[Holocaust]] survivor. His experiences in four different [[Nazism|Nazi]] [[concentration camp]]s during [[World War II]], beginning at the age of 15, and the loss of his parents and sister in the camps, shaped his life and his activism. |

| − | + | Wiesel was a passionate and powerful writer and author of more than forty books. His best-known work, ''Night,'' is a memoir of his life in the concentration camps, which has been translated into thirty languages. Together with his wife, Marion, he spent his adult life writing, speaking, and working for peace and advocating for victims of injustice throughout the world. | |

| − | + | Wiesel is the recipient of the American [[Congressional Gold Medal]] and [[Presidential Medal of Freedom]] and the ''Grand Croix'' of the French Legion of Honor, as well as an Honorary Knighthood from Great Britain. Awarded the [[Nobel Peace Prize]] in December 1986, Wiesel summarized his philosophy in his acceptance speech: | |

| + | <blockquote>As long as one dissident is in prison, our freedom will not be true. As long as one child is hungry, our life will be filled with anguish and shame. What all these victims need above all is to know that they are not alone; that we are not forgetting them, that when their voices are stifled we shall lend them ours, that while their freedom depends on ours, the quality of our freedom depends on theirs.<ref>Elie Wiesel, [https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1986/wiesel-acceptance.html Nobel Acceptance Speech,] ''NobelPrize.org.'' Retrieved January 3, 2017.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | "What I want, what I’ve hoped for all my life," Weisel has written, "is that my past should not become your children’s future."<ref>PBS, [http://www.pbs.org/speaktruthtopower/elie.html Speak Truth to Power,] ''Umbrage Editions.'' Retrieved January 3, 2017.</ref> | ||

| − | Wiesel | + | == Early life == |

| + | Eliezer Wiesel was born September 30, 1928, in the provincial town of Sighet, [[Transylvania]], which is now part of [[Romania]]. A Jewish community had existed there since 1640, when it sought refuge from an outbreak of pogroms and persecution in the [[Ukraine]]. | ||

| − | + | His parents were Shlomo and Sarah Wiesel. Sarah was the daughter of Reb Dodye Feig, a devout [[Hasidic Judaism|Hasidic Jew]]. Weisel was strongly influenced by his maternal grandfather, who inspired him to pursue [[Talmud|Talmudic]] studies in the town's Yeshiva. His father Shlomo, who ran a grocery store, was also religious, but considered himself an emancipated Jew. Abreast of the current affairs of the world, he wanted his children to be equally attuned. He thus insisted that his son study modern [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] in addition to the Talmud, so that he could read the works of contemporary writers.<ref name=PBS>PBS, [http://www.pbs.org/eliewiesel/life/index.html The Life and Work of Wiesel.] ''Lives and Legacies Films, Inc.'' Retrieved January 3, 2017.</ref> | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | Wiesel | + | Wiesel's father was active and trusted within the community, even having spent a few months in jail for helping [[Poland|Polish]] [[Jews]] who escaped to Hungary in the early years of the war. It was he who was credited with instilling a strong sense of [[humanism]] in his son. It was he who encouraged him to read literature, whereas his mother encouraged him to study [[Torah]] and [[Kabbalah]]. Wiesel has said his father represented reason, and his mother, faith.<ref>Ellen S. Fine, ''Legacy of Night: The Literary Universe of Elie Wiesel'' (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1982).</ref> |

| − | + | Elie Wiesel had three sisters, Hilda, Béa, and Tzipora. Tzipora is believed to have perished in the [[Holocaust]] along with their mother. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | At home in Sighet, which was close to the [[Hungary|Hungarian]] border, Wiesel's family spoke mostly Yiddish, but also [[German language|German]], Hungarian, and Romanian. Today, Wiesel says that he "thinks in Yiddish, writes in French, and, with his wife Marion and his son Elisha, lives his life in English."<ref name=PBS/> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | == The Holocaust == | |

| − | + | <blockquote>Never shall I forget that night, the first night in the camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky. Never shall I forget those flames which consumed my faith forever…Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God Himself. Never.<ref>Elie Wiesel, ''Night'' (New York: Hill and Wang, 1958, ISBN 0553272535).</ref></blockquote> | |

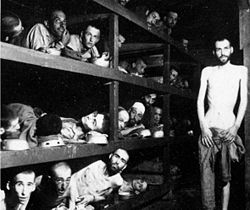

| − | + | [[Image:Buchenwald.jpg|thumb|250px|Buchenwald, 1945. Wiesel is on the second row, seventh from the left.]] | |

| − | + | ||

| + | [[Anti-Semitism]] was common in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, though its roots go back much further. In 1936, Jews were banned from all professional jobs, effectively preventing them from exerting any influence in education, politics, higher education, and industry. By the end of 1938, Jewish children had been banned from attending normal schools. By the following spring, nearly all Jewish companies had either collapsed under financial pressure and declining profits, or had been forced to sell out to the [[Nazism|Nazi]]-German government as part of the "Aryanization" policy inaugurated in 1937. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As [[World War II]] began, large massacres of [[Jew]]s took place, and, by December 1941, [[Adolf Hitler]] decided to completely exterminate European Jews. Soon, a "Final Solution of the Jewish question" had been worked out and Jewish populations from the ghettos and all occupied territories began to be deported to the seven camps designated extermination camps ([[Auschwitz]], Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek, Maly Trostenets, Sobibór, and [[Treblinka]]). The town of Sighet had been annexed to [[Hungary]] in 1940, and in 1944, the Hungarian authorities deported the Jewish community in Sighet to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Elie Wiesel was 15 years old at the time. | ||

| − | + | Wiesel was separated from his mother and sister, Tzipora, who are presumed to have been killed at Auschwitz. Wiesel and his father were sent to the attached work camp Buna-Werke, a subcamp of Auschwitz III Monowitz. They managed to remain together for a year as they were forced to work under appalling conditions and shuffled between concentration camps in the closing days of the war. All Jews in concentration camps were tattooed with identification numbers; young Wiesel had the number A-7713 tattooed into his left arm. | |

| − | + | On January 28, 1945, just a few weeks after the two were marched to [[Buchenwald]] and only months before the camp was liberated by the [[United States|American]] Third Army, Wiesel's father died of [[dysentery]], [[starvation]], and [[exhaustion]], after being beaten by a guard. It is said that the last word his father spoke was “Eliezer,” his son's name. | |

| − | + | By the end of the war, much of the Jewish population of [[Europe]] had been killed in the [[Holocaust]]. [[Poland]], home of the largest Jewish community in the world before the war, had over 90 percent of its Jewish population, or about 3,000,000 Jews, killed. Hungary, Wiesel's home nation, lost over 70 percent of its Jewish population. | |

| − | == | + | ==After the war== |

| − | + | [[File:Child_survivors_of_Auschwitz.jpeg|thumb|right|250px|left|Child survivors of the Holocaust filmed during the liberation of Auschwitz concentration camp by the Red Army, January 1945.]] | |

| − | + | After being liberated from [[Auschwitz|Auschwitz—Buchenwald]], Wiesel was sent to [[France]] with a group of Jewish children who had been orphaned during the [[Holocaust]]. Here, he was reunited with his two older sisters, Hilda and Bea, who had also survived the war. He was given a choice between secular or religious studies. Even though his faith had been severely wounded by his experiences in Auschwitz, and feeling that God had turned his back on the Jewish race, he chose to return to religious studies. After several years of preparatory schools, Wiesel was sent to [[Paris]] to study at the [[Sorbonne]], where he studied [[philosophy]]. | |

| + | {{readout||left|250px|Elie Wiesel refused to write or talk about his experiences in the [[Holocaust]] for 10 years after his liberation}} | ||

| + | He taught [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] and worked as a translator and choirmaster before becoming a professional [[journalist]] for [[Israel]]i and [[French Language|French]] newspapers. However, for 10 years after the war, Wiesel refused to write about or discuss his experiences during the Holocaust. Like many survivors, Wiesel could not find the words to describe his experiences. However, a meeting with [[François Mauriac]], the distinguished French Catholic writer and 1952 Nobel Laureate in Literature, who eventually became his close friend, persuaded him to write about his Holocaust experiences. | ||

| − | + | The result was his first work, the 800–page ''And the World Remained Silent,'' written in Yiddish. The book was originally rejected with the reasoning that by that time (1956) "no one is interested in the death camps anymore." Wiesel's response was that "not to transmit an experience is to betray it." This semi-biographical work was abridged and published two years later as ''Night,'' becoming an internationally acclaimed best-seller that has been translated into thirty languages. Proceeds from this work go to support a [[yeshiva]] in [[Israel]] established by Wiesel in memory of his father. Since that time, Wiesel has dedicated his life to ensuring that the horror of the Holocaust would never be forgotten, and that [[genocide|genocidal]] homicide would never again be practiced toward any race of people. | |

| − | Wiesel | + | === An author and emigré === |

| + | Wiesel was assigned to [[New York]] in 1956, as a foreign correspondent for the [[Israel]]i newspaper, ''Yedioth Ahronoth''. While living there, he was struck by a taxi, hospitalized for months, and confined to a wheelchair for over a year. Still classified as a [[stateless person]], he was unable to travel to [[France]] to renew his identity card and unable to receive a [[United States|U.S.]] visa without it. However, he found that he was eligible to become a legal resident. Five years later, in 1963, he became a United States citizen and received an American passport, the first passport he had ever had. Years later, when his then close friend [[Francois Mitterand]] became President of France, he was offered French nationality. "Though I thanked him," he writes in his memoirs, "and not without some emotion, I declined the offer. When I had needed a passport, it was America that had given me one."<ref name=PBS/> In 1969, Wiesel married Marion Erster Rose, a survivor of the [[Germany|German]] concentration camps. | ||

| − | + | Since emigrating to the [[United States]], Wiesel has written over forty books, both fiction and non-fiction, as well as essays and plays. His writing is considered among the most important works regarding the [[Holocaust]], which he describes as "history's worst crime." Most of Wiesel's novels take place either before or after the events of the Holocaust, which has been the central theme of his writing. The conflict of doubt and belief in God, his seeming silence in the suffering, despair and hope of humanity is recurrent in his works. Wiesel has reported that during his time in the concentration camps, the prisoners were able to keep faith and hope because they held the belief that the world just did not know what was happening, and that as soon as the existence of the camps was made known, America and the world would come to their rescue. His heartbreak, and the heartbreak of many, was in discovering that the knowledge was there, but the world took years to respond. | |

| − | Wiesel | + | His many novels have been written to give voice to those who perished in obscurity. Beginning in the 1990s, Wiesel began devoting much of his time to the publication of his memoirs. The first part, ''All Rivers Run in to the Sea,'' appeared in 1995, and the second, ''And the Sea is Never Full,'' in 1999. In the latter, Wiesel wrote: |

| + | <blockquote>The silence of Birkenau is a silence unlike any other. It contains the screams, the strangled prayers of thousands of human beings condemned to vanish into the darkness of nameless, endless ashes. Human silence at the core of inhumanity. Deadly silence at the core of death. Eternal silence under a moribund sky.<ref>Elie Wiesel, ''And the Sea Is Never Full: Memoirs, 1969-'' (Knopf, 1999, ISBN 978-0679439172), 191. </ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | Wiesel | + | === Activism === |

| + | Wiesel and his wife, Marion, created the ''Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity'' soon after he was awarded the 1986 Nobel Prize for Peace. The Foundation's mission, rooted in the memory of the Holocaust, is to "combat indifference, intolerance, and injustice through international dialogue and youth-focused programs that promote acceptance, understanding and equality."<ref>The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity, [http://www.eliewieselfoundation.org/aboutus.aspx Create Change.] Retrieved January 3, 2017.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Wiesel served as chairman for the ''Presidential Commission on the Holocaust'' (later renamed ''U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council'') from 1978 to 1986, spearheading the building of the [[United States Holocaust Memorial Museum|Memorial Museum]] in [[Washington, DC]]. In 1993, Wiesel spoke at the dedication of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. Along with [[Bill Clinton|President Clinton]] he lit the eternal flame in the memorial's ''Hall of Remembrance''. His words, which echo his life’s work, are carved in stone at the entrance to the museum: “For the dead and the living, we must bear witness."<ref>Michael Pariser, ''Elie Wiesel'' (Brookfield: The Millbrook Press, 1994), p. 43. </ref> | |

| − | + | He was an active teacher, holding the position of Andrew Mellon Professor of the [[Humanities]] at [[Boston University]] from 1976. From 1972 to 1976, Wiesel was a Distinguished Professor at the City University of New York. In 1982, he served as the first [[Henry Luce]] Visiting Scholar in Humanities and Social Thought at [[Yale University]]. He has also instructed courses at several universities. From 1997 to 1999, he was Ingeborg Rennert Visiting Professor of [[Judaic Studies]] at Barnard College of [[Columbia University]]. | |

| − | + | Wiesel was a popular speaker on the [[Holocaust]]. As a political activist, he has also advocated for many causes, including [[Israel]], the plight of [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] and [[Ethiopia]]n [[Jew]]s, the victims of ''[[apartheid]]'' in [[South Africa]], [[Argentina]]'s ''Desaparecidos,'' [[Bosnia|Bosnian]] victims of [[ethnic cleansing]] in the former [[Yugoslavia]], [[Nicaragua]]'s [[Miskito]] Indians, and the [[Kurds]]. He also recently voiced support for intervention in [[Darfur]], [[Sudan]]. | |

| − | + | Weisel also led a commission organized by the [[Romania]]n government to research and write a report, released in 2004, on the true history of the [[Holocaust]] in Romania and the involvement of the Romanian wartime regime in atrocities against Jews and other groups, including the [[Roma]] peoples. The Romanian government accepted the findings in the report and committed to implementing the commission's recommendations for educating the public on the history of the Holocaust in Romania. The commission, formally called the International Commission for the Study of the Holocaust in Romania, came to be called the [[Wiesel Commission]] in Elie Wiesel's honor and due to his leadership. | |

| − | + | Wiesel served as the honorary chair of the Habonim Dror Camp Miriam Campership and Building Fund, and a member of the International Council of the New York-based [[Human Rights Foundation]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | === Awards and recognitions === | |

| + | Weisel is the recipient of 110 honorary degrees from academic institutions, among them the ''Jewish Theological Seminary,'' ''Hebrew Union College,'' ''Yale University,'' ''Boston University,'' ''Brandeis,'' and the ''University of Notre Dame''. He has won more than 120 other honors, and more than fifty books have been written about him. | ||

| − | + | In 1995, he was included as one of fifty great Americans in the special fiftieth edition of ''Who's Who In America''. In 1985, [[Ronald Reagan|President Reagan]] presented him with the [[Congressional Gold Medal]], and in 1992, he received the [[Presidential Medal of Freedom]] from [[George H. W. Bush|President Bush]]. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1996. He has also been awarded the ''Grand Croix'' of the French Legion of Honor. | |

| − | + | Elie Wiesel was awarded the [[Nobel Peace Prize]] in 1986 for speaking out against violence, repression, and [[racism]]. In their determination, The Norwegian Nobel Committee stated that: <blockquote>Elie Wiesel has emerged as one of the most important spiritual leaders and guides in an age when violence, repression, and racism continue to characterize the world. Wiesel is a messenger to humankind; his message is one of peace, atonement and human dignity… Wiesel's commitment, which originated in the sufferings of the Jewish people, has been widened to embrace all repressed peoples and races. <ref>The Norwegian Nobel Committee, [http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1986/press.html The Nobel Peace Prize for 1986.] Retrieved January 3, 2017. </ref></blockquote> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ==Death== | |

| − | + | Wiesel died on the morning of July 2, 2016 at his home in [[Manhattan]], aged 87.<ref>Alan Yuhas, [https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/jul/02/elie-wiesel-nobel-winner-holocaust-survivor-dies Elie Wiesel, Nobel winner and Holocaust survivor, dies aged 87] ''The Guardian'', July 2, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2017.</ref><ref> Ronen Shnidman, [http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/1.575072 Elie Wiesel, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and renowned Holocaust survivor, dies at 87] ''Haaretz'', July 2, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2017.</ref> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Utah senator [[Orrin Hatch]] paid tribute to Wiesel in a speech on the Senate floor the following week, where he said that "With Elie's passing we have lost a beacon of humanity and hope. We have lost a hero of human rights and a luminary of Holocaust literature."<ref>[http://www.weeklystandard.com/orrin-hatch-pays-tribute-to-elie-wiesel/article/2003215 "Orrin Hatch Pays Tribute to Elie Wiesel"], ''The Weekly Standard'', July 8, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2017.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Quotes== | ==Quotes== | ||

| + | * "I was the accuser, God the accused. My eyes were open and I was alone—terribly alone in a world without God and without man." ''Night'' | ||

| + | |||

* "Always question those who are certain of what they are saying." | * "Always question those who are certain of what they are saying." | ||

| − | * " | + | * "…I wanted to believe in it. In my eyes, to be a human was to belong to the human community in the broadest and most immediate sense. It was to feel abused whenever a person, any person anywhere, was humiliated…" ''All Rivers Run to the Sea |

* "Take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented." | * "Take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented." | ||

| − | * "I have learned two things in my life; first, there are no sufficient literary, psychological, or historical answers to human tragedy, only moral ones. | + | * "I have learned two things in my life; first, there are no sufficient literary, psychological, or historical answers to human tragedy, only moral ones. Second, just as despair can come to another only from other human beings, hope, too, can be given to one only by other human beings." |

* "God made man because He loves stories." | * "God made man because He loves stories." | ||

| − | == | + | == Major works == |

| − | * | + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Un di velt hot geshvign'', Buenos Ayres, Tsentral-Farband fun Poylishe Yidn in Argentine, 716, 1956, ISBN 0374521409. |

| − | * | + | ** Wiesel, Elie. ''Night.'' New York: Hill and Wang, 1958. ISBN 0553272535. |

| − | * | + | ** Wiesel, Elie. ''Dawn.'' New York: Hill and Wang 1961, 2006. ISBN 0553225367. |

| − | * | + | ** Wiesel, Elie. ''Day.'' New York: Hill and Wang 1962. ISBN 0553581708. |

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''The Town Beyond the Wall.'' New York: Rinehart and Winston, 1964. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''The Gates of the Forest.'' New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1966. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''The Jews of Silence.'' New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1966. ISBN 0935613013. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Legends of our Time.'' New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1968. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''A Beggar in Jerusalem.'' New York: Pocket Books, 1970. ISBN 067181253X. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''One Generation After.'' New York: Random House, 1970. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Souls on Fire; portraits and legends of Hasidic masters.'' New York: Random House, 1972. ISBN 067144171X. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Night Trilogy.'' New York: Hill and Wang, 1972. ISBN 0374521409. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''The Oath.'' New York: Random House, 1973. ISBN 9780394487793. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Ani Maamin.'' New York: Random House, 1974. ISBN 9780394487700. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Zalmen, or the Madness of God.'' New York: Random House, 1974. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Messengers of God: Biblical Portraits and Legends.'' Random House, 1976. ISBN 9780394497402. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''A Jew Today.'' Random House, 1978. ISBN 0935613153. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Four Hasidic Masters.'' Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1978. ISBN 9780268009441. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Images from the Bible.'' New York: Overlook Press, 1980. ISBN 9780879511074. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''The Trial of God.'' Random House, 1979. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''The Testament.'' New York: Summit Books, 1981. ISBN 9780671448332. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Five Biblical Portraits.'' Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1981. ISBN 0268009570. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Somewhere a Master.'' New York: Summit Books, 1982. ISBN 9780671441708. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''The Golem.'' Summit, 1983. ISBN 0671496247. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''The Fifth Son.'' New York: Summit Books, 1985. ISBN 9780671523312. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Against Silence.'' New York: Holocaust Library, 1985. ISBN 9780805250480. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Twilight.'' New York: Summit Books, 1988. ISBN 9780671644079. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''The Six Days of Destruction.'' New York: Pergamon Press, 1988. ISBN 9780080365053. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''A Journey of Faith.'' New York: Donald I. Fine, 1990. ISBN 1556112173. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''From the Kingdom of Memory.'' New York: Summit Books, 1990. ISBN 9780671523329. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Evil and Exile.'' Notre Dame, University of Notre Dame Press, 1990. ISBN 9780268009229. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Sages and Dreamers.'' New York: Summit Books, 1991. ISBN 9780671746797. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''The Forgotten.'' New York: Schocken Books, 1995. ISBN 0805210199. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''A Passover Haggadah.'' New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993. ISBN 9780671735418. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''All Rivers Run to the Sea: Memoirs.'' New York: Schocken Books, 1996. ISBN 9780805210286. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie, and Francois Mitterrand. ''Memoir in Two Voices.'' New York: Little, Brown, 1996. ISBN 9781559703383. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''King Solomon and his Magic.'' New York: Greenwillow Books, 1999. ISBN 9780688169596. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Conversations with Elie Wiesel.'' New York: Schocken Books, 2001. ISBN 9780805241921. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''The Judges.'' Prince Frederick, 2002. ISBN 9781417573486. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''Wise Men and Their Tales.'' New York: Schocken Books, 2003. ISBN 9780805241730. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''The Time of the Uprooted.'' New York: Knopf, 2005. ISBN 9781400041725. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''All Rivers Run to the Sea: Memoirs.'' New York: Alfred Knopf, 1995. ISBN 9780679439165. | ||

| + | * Wiesel, Elie. ''And the Sea is Never Full: Memoirs 1969-.'' New York: Alfred Knopf, 1999. ISBN 9780679439172. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Notes== |

| − | <references /> | + | <references/> |

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | * Chmiel, Mark. ''Elie Wiesel and the Politics of Moral Leadership.'' Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-1566398572. | |

| − | * | + | * Fine, Ellen S. ''Legacy of Night: The Literary Universe of Elie Wiesel.'' Albany: State University of New York Press, 1982. ISBN 0873955900. |

| − | + | * Pariser, Michael. ''Elie Wiesel''. Brookfield: The Millbrook Press, 1994. ISBN 978-1562947439 | |

| − | + | * Rittner, Carol. ''Elie Wiesel: Between Memory and Hope.'' New York: New York University Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0814774106. | |

| − | + | * Rosenfeld, Alvin H., and Irving Greenberg. ''Confronting the Holocaust: The Impact of Elie Wiesel.'' Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1978. ISBN 978-0253112903. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | *Fine, Ellen S. ''Legacy of Night: The Literary Universe of Elie Wiesel'' | + | ==External links== |

| − | * | + | All links retrieved February 13, 2024. |

| − | * | + | |

| − | * [http:// | + | * [http://www.pbs.org/eliewiesel/ The Life and Work of Wiesel] ''Public Broadcasting Service''. |

| − | *[http://www. | + | * [http://www.historyplace.com/speeches/wiesel.htm Elie Wiesel "The Perils of Indifference"], ''The History Place''. |

| − | * [http://www.mediamonitors.net/amr9.html Elie Wiesel | + | * [http://www.mediamonitors.net/amr9.html Elie Wiesel Must Respect Palestinian Memories.] ''Media Monitors Network''. |

| + | ---- | ||

{{Nobel Peace Prize Laureates 1976-2000}} | {{Nobel Peace Prize Laureates 1976-2000}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | [[Category:Politicians and reformers]] |

| − | [[ | + | [[Category:Nobel Peace Prize Winners]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credit|96285169}} | {{credit|96285169}} | ||

Latest revision as of 16:12, 13 February 2024

| |

| Born: | September 30 1928 Sighet, Maramureş County, Romania |

|---|---|

| Died: | July 2 2016 (aged 87) New York City |

| Occupation(s): | political activist, professor |

| Magnum opus: | Night |

Eliezer Wiesel (commonly known as Elie) (September 30, 1928 - July 2, 2016) was a world-renowned Hungarian Romanian Jewish novelist, philosopher, humanitarian, political activist, and Holocaust survivor. His experiences in four different Nazi concentration camps during World War II, beginning at the age of 15, and the loss of his parents and sister in the camps, shaped his life and his activism.

Wiesel was a passionate and powerful writer and author of more than forty books. His best-known work, Night, is a memoir of his life in the concentration camps, which has been translated into thirty languages. Together with his wife, Marion, he spent his adult life writing, speaking, and working for peace and advocating for victims of injustice throughout the world.

Wiesel is the recipient of the American Congressional Gold Medal and Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Grand Croix of the French Legion of Honor, as well as an Honorary Knighthood from Great Britain. Awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in December 1986, Wiesel summarized his philosophy in his acceptance speech:

As long as one dissident is in prison, our freedom will not be true. As long as one child is hungry, our life will be filled with anguish and shame. What all these victims need above all is to know that they are not alone; that we are not forgetting them, that when their voices are stifled we shall lend them ours, that while their freedom depends on ours, the quality of our freedom depends on theirs.[1]

"What I want, what I’ve hoped for all my life," Weisel has written, "is that my past should not become your children’s future."[2]

Early life

Eliezer Wiesel was born September 30, 1928, in the provincial town of Sighet, Transylvania, which is now part of Romania. A Jewish community had existed there since 1640, when it sought refuge from an outbreak of pogroms and persecution in the Ukraine.

His parents were Shlomo and Sarah Wiesel. Sarah was the daughter of Reb Dodye Feig, a devout Hasidic Jew. Weisel was strongly influenced by his maternal grandfather, who inspired him to pursue Talmudic studies in the town's Yeshiva. His father Shlomo, who ran a grocery store, was also religious, but considered himself an emancipated Jew. Abreast of the current affairs of the world, he wanted his children to be equally attuned. He thus insisted that his son study modern Hebrew in addition to the Talmud, so that he could read the works of contemporary writers.[3]

Wiesel's father was active and trusted within the community, even having spent a few months in jail for helping Polish Jews who escaped to Hungary in the early years of the war. It was he who was credited with instilling a strong sense of humanism in his son. It was he who encouraged him to read literature, whereas his mother encouraged him to study Torah and Kabbalah. Wiesel has said his father represented reason, and his mother, faith.[4]

Elie Wiesel had three sisters, Hilda, Béa, and Tzipora. Tzipora is believed to have perished in the Holocaust along with their mother.

At home in Sighet, which was close to the Hungarian border, Wiesel's family spoke mostly Yiddish, but also German, Hungarian, and Romanian. Today, Wiesel says that he "thinks in Yiddish, writes in French, and, with his wife Marion and his son Elisha, lives his life in English."[3]

The Holocaust

Never shall I forget that night, the first night in the camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky. Never shall I forget those flames which consumed my faith forever…Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God Himself. Never.[5]

Anti-Semitism was common in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, though its roots go back much further. In 1936, Jews were banned from all professional jobs, effectively preventing them from exerting any influence in education, politics, higher education, and industry. By the end of 1938, Jewish children had been banned from attending normal schools. By the following spring, nearly all Jewish companies had either collapsed under financial pressure and declining profits, or had been forced to sell out to the Nazi-German government as part of the "Aryanization" policy inaugurated in 1937.

As World War II began, large massacres of Jews took place, and, by December 1941, Adolf Hitler decided to completely exterminate European Jews. Soon, a "Final Solution of the Jewish question" had been worked out and Jewish populations from the ghettos and all occupied territories began to be deported to the seven camps designated extermination camps (Auschwitz, Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek, Maly Trostenets, Sobibór, and Treblinka). The town of Sighet had been annexed to Hungary in 1940, and in 1944, the Hungarian authorities deported the Jewish community in Sighet to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Elie Wiesel was 15 years old at the time.

Wiesel was separated from his mother and sister, Tzipora, who are presumed to have been killed at Auschwitz. Wiesel and his father were sent to the attached work camp Buna-Werke, a subcamp of Auschwitz III Monowitz. They managed to remain together for a year as they were forced to work under appalling conditions and shuffled between concentration camps in the closing days of the war. All Jews in concentration camps were tattooed with identification numbers; young Wiesel had the number A-7713 tattooed into his left arm.

On January 28, 1945, just a few weeks after the two were marched to Buchenwald and only months before the camp was liberated by the American Third Army, Wiesel's father died of dysentery, starvation, and exhaustion, after being beaten by a guard. It is said that the last word his father spoke was “Eliezer,” his son's name.

By the end of the war, much of the Jewish population of Europe had been killed in the Holocaust. Poland, home of the largest Jewish community in the world before the war, had over 90 percent of its Jewish population, or about 3,000,000 Jews, killed. Hungary, Wiesel's home nation, lost over 70 percent of its Jewish population.

After the war

After being liberated from Auschwitz—Buchenwald, Wiesel was sent to France with a group of Jewish children who had been orphaned during the Holocaust. Here, he was reunited with his two older sisters, Hilda and Bea, who had also survived the war. He was given a choice between secular or religious studies. Even though his faith had been severely wounded by his experiences in Auschwitz, and feeling that God had turned his back on the Jewish race, he chose to return to religious studies. After several years of preparatory schools, Wiesel was sent to Paris to study at the Sorbonne, where he studied philosophy.

He taught Hebrew and worked as a translator and choirmaster before becoming a professional journalist for Israeli and French newspapers. However, for 10 years after the war, Wiesel refused to write about or discuss his experiences during the Holocaust. Like many survivors, Wiesel could not find the words to describe his experiences. However, a meeting with François Mauriac, the distinguished French Catholic writer and 1952 Nobel Laureate in Literature, who eventually became his close friend, persuaded him to write about his Holocaust experiences.

The result was his first work, the 800–page And the World Remained Silent, written in Yiddish. The book was originally rejected with the reasoning that by that time (1956) "no one is interested in the death camps anymore." Wiesel's response was that "not to transmit an experience is to betray it." This semi-biographical work was abridged and published two years later as Night, becoming an internationally acclaimed best-seller that has been translated into thirty languages. Proceeds from this work go to support a yeshiva in Israel established by Wiesel in memory of his father. Since that time, Wiesel has dedicated his life to ensuring that the horror of the Holocaust would never be forgotten, and that genocidal homicide would never again be practiced toward any race of people.

An author and emigré

Wiesel was assigned to New York in 1956, as a foreign correspondent for the Israeli newspaper, Yedioth Ahronoth. While living there, he was struck by a taxi, hospitalized for months, and confined to a wheelchair for over a year. Still classified as a stateless person, he was unable to travel to France to renew his identity card and unable to receive a U.S. visa without it. However, he found that he was eligible to become a legal resident. Five years later, in 1963, he became a United States citizen and received an American passport, the first passport he had ever had. Years later, when his then close friend Francois Mitterand became President of France, he was offered French nationality. "Though I thanked him," he writes in his memoirs, "and not without some emotion, I declined the offer. When I had needed a passport, it was America that had given me one."[3] In 1969, Wiesel married Marion Erster Rose, a survivor of the German concentration camps.

Since emigrating to the United States, Wiesel has written over forty books, both fiction and non-fiction, as well as essays and plays. His writing is considered among the most important works regarding the Holocaust, which he describes as "history's worst crime." Most of Wiesel's novels take place either before or after the events of the Holocaust, which has been the central theme of his writing. The conflict of doubt and belief in God, his seeming silence in the suffering, despair and hope of humanity is recurrent in his works. Wiesel has reported that during his time in the concentration camps, the prisoners were able to keep faith and hope because they held the belief that the world just did not know what was happening, and that as soon as the existence of the camps was made known, America and the world would come to their rescue. His heartbreak, and the heartbreak of many, was in discovering that the knowledge was there, but the world took years to respond.

His many novels have been written to give voice to those who perished in obscurity. Beginning in the 1990s, Wiesel began devoting much of his time to the publication of his memoirs. The first part, All Rivers Run in to the Sea, appeared in 1995, and the second, And the Sea is Never Full, in 1999. In the latter, Wiesel wrote:

The silence of Birkenau is a silence unlike any other. It contains the screams, the strangled prayers of thousands of human beings condemned to vanish into the darkness of nameless, endless ashes. Human silence at the core of inhumanity. Deadly silence at the core of death. Eternal silence under a moribund sky.[6]

Activism

Wiesel and his wife, Marion, created the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity soon after he was awarded the 1986 Nobel Prize for Peace. The Foundation's mission, rooted in the memory of the Holocaust, is to "combat indifference, intolerance, and injustice through international dialogue and youth-focused programs that promote acceptance, understanding and equality."[7]

Wiesel served as chairman for the Presidential Commission on the Holocaust (later renamed U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council) from 1978 to 1986, spearheading the building of the Memorial Museum in Washington, DC. In 1993, Wiesel spoke at the dedication of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. Along with President Clinton he lit the eternal flame in the memorial's Hall of Remembrance. His words, which echo his life’s work, are carved in stone at the entrance to the museum: “For the dead and the living, we must bear witness."[8]

He was an active teacher, holding the position of Andrew Mellon Professor of the Humanities at Boston University from 1976. From 1972 to 1976, Wiesel was a Distinguished Professor at the City University of New York. In 1982, he served as the first Henry Luce Visiting Scholar in Humanities and Social Thought at Yale University. He has also instructed courses at several universities. From 1997 to 1999, he was Ingeborg Rennert Visiting Professor of Judaic Studies at Barnard College of Columbia University.

Wiesel was a popular speaker on the Holocaust. As a political activist, he has also advocated for many causes, including Israel, the plight of Soviet and Ethiopian Jews, the victims of apartheid in South Africa, Argentina's Desaparecidos, Bosnian victims of ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia, Nicaragua's Miskito Indians, and the Kurds. He also recently voiced support for intervention in Darfur, Sudan.

Weisel also led a commission organized by the Romanian government to research and write a report, released in 2004, on the true history of the Holocaust in Romania and the involvement of the Romanian wartime regime in atrocities against Jews and other groups, including the Roma peoples. The Romanian government accepted the findings in the report and committed to implementing the commission's recommendations for educating the public on the history of the Holocaust in Romania. The commission, formally called the International Commission for the Study of the Holocaust in Romania, came to be called the Wiesel Commission in Elie Wiesel's honor and due to his leadership.

Wiesel served as the honorary chair of the Habonim Dror Camp Miriam Campership and Building Fund, and a member of the International Council of the New York-based Human Rights Foundation.

Awards and recognitions

Weisel is the recipient of 110 honorary degrees from academic institutions, among them the Jewish Theological Seminary, Hebrew Union College, Yale University, Boston University, Brandeis, and the University of Notre Dame. He has won more than 120 other honors, and more than fifty books have been written about him.

In 1995, he was included as one of fifty great Americans in the special fiftieth edition of Who's Who In America. In 1985, President Reagan presented him with the Congressional Gold Medal, and in 1992, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Bush. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1996. He has also been awarded the Grand Croix of the French Legion of Honor.

Elie Wiesel was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986 for speaking out against violence, repression, and racism. In their determination, The Norwegian Nobel Committee stated that:

Elie Wiesel has emerged as one of the most important spiritual leaders and guides in an age when violence, repression, and racism continue to characterize the world. Wiesel is a messenger to humankind; his message is one of peace, atonement and human dignity… Wiesel's commitment, which originated in the sufferings of the Jewish people, has been widened to embrace all repressed peoples and races. [9]

Death

Wiesel died on the morning of July 2, 2016 at his home in Manhattan, aged 87.[10][11]

Utah senator Orrin Hatch paid tribute to Wiesel in a speech on the Senate floor the following week, where he said that "With Elie's passing we have lost a beacon of humanity and hope. We have lost a hero of human rights and a luminary of Holocaust literature."[12]

Quotes

- "I was the accuser, God the accused. My eyes were open and I was alone—terribly alone in a world without God and without man." Night

- "Always question those who are certain of what they are saying."

- "…I wanted to believe in it. In my eyes, to be a human was to belong to the human community in the broadest and most immediate sense. It was to feel abused whenever a person, any person anywhere, was humiliated…" All Rivers Run to the Sea

- "Take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented."

- "I have learned two things in my life; first, there are no sufficient literary, psychological, or historical answers to human tragedy, only moral ones. Second, just as despair can come to another only from other human beings, hope, too, can be given to one only by other human beings."

- "God made man because He loves stories."

Major works

- Wiesel, Elie. Un di velt hot geshvign, Buenos Ayres, Tsentral-Farband fun Poylishe Yidn in Argentine, 716, 1956, ISBN 0374521409.

- Wiesel, Elie. Night. New York: Hill and Wang, 1958. ISBN 0553272535.

- Wiesel, Elie. Dawn. New York: Hill and Wang 1961, 2006. ISBN 0553225367.

- Wiesel, Elie. Day. New York: Hill and Wang 1962. ISBN 0553581708.

- Wiesel, Elie. The Town Beyond the Wall. New York: Rinehart and Winston, 1964.

- Wiesel, Elie. The Gates of the Forest. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1966.

- Wiesel, Elie. The Jews of Silence. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1966. ISBN 0935613013.

- Wiesel, Elie. Legends of our Time. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1968.

- Wiesel, Elie. A Beggar in Jerusalem. New York: Pocket Books, 1970. ISBN 067181253X.

- Wiesel, Elie. One Generation After. New York: Random House, 1970.

- Wiesel, Elie. Souls on Fire; portraits and legends of Hasidic masters. New York: Random House, 1972. ISBN 067144171X.

- Wiesel, Elie. Night Trilogy. New York: Hill and Wang, 1972. ISBN 0374521409.

- Wiesel, Elie. The Oath. New York: Random House, 1973. ISBN 9780394487793.

- Wiesel, Elie. Ani Maamin. New York: Random House, 1974. ISBN 9780394487700.

- Wiesel, Elie. Zalmen, or the Madness of God. New York: Random House, 1974.

- Wiesel, Elie. Messengers of God: Biblical Portraits and Legends. Random House, 1976. ISBN 9780394497402.

- Wiesel, Elie. A Jew Today. Random House, 1978. ISBN 0935613153.

- Wiesel, Elie. Four Hasidic Masters. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1978. ISBN 9780268009441.

- Wiesel, Elie. Images from the Bible. New York: Overlook Press, 1980. ISBN 9780879511074.

- Wiesel, Elie. The Trial of God. Random House, 1979.

- Wiesel, Elie. The Testament. New York: Summit Books, 1981. ISBN 9780671448332.

- Wiesel, Elie. Five Biblical Portraits. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1981. ISBN 0268009570.

- Wiesel, Elie. Somewhere a Master. New York: Summit Books, 1982. ISBN 9780671441708.

- Wiesel, Elie. The Golem. Summit, 1983. ISBN 0671496247.

- Wiesel, Elie. The Fifth Son. New York: Summit Books, 1985. ISBN 9780671523312.

- Wiesel, Elie. Against Silence. New York: Holocaust Library, 1985. ISBN 9780805250480.

- Wiesel, Elie. Twilight. New York: Summit Books, 1988. ISBN 9780671644079.

- Wiesel, Elie. The Six Days of Destruction. New York: Pergamon Press, 1988. ISBN 9780080365053.

- Wiesel, Elie. A Journey of Faith. New York: Donald I. Fine, 1990. ISBN 1556112173.

- Wiesel, Elie. From the Kingdom of Memory. New York: Summit Books, 1990. ISBN 9780671523329.

- Wiesel, Elie. Evil and Exile. Notre Dame, University of Notre Dame Press, 1990. ISBN 9780268009229.

- Wiesel, Elie. Sages and Dreamers. New York: Summit Books, 1991. ISBN 9780671746797.

- Wiesel, Elie. The Forgotten. New York: Schocken Books, 1995. ISBN 0805210199.

- Wiesel, Elie. A Passover Haggadah. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993. ISBN 9780671735418.

- Wiesel, Elie. All Rivers Run to the Sea: Memoirs. New York: Schocken Books, 1996. ISBN 9780805210286.

- Wiesel, Elie, and Francois Mitterrand. Memoir in Two Voices. New York: Little, Brown, 1996. ISBN 9781559703383.

- Wiesel, Elie. King Solomon and his Magic. New York: Greenwillow Books, 1999. ISBN 9780688169596.

- Wiesel, Elie. Conversations with Elie Wiesel. New York: Schocken Books, 2001. ISBN 9780805241921.

- Wiesel, Elie. The Judges. Prince Frederick, 2002. ISBN 9781417573486.

- Wiesel, Elie. Wise Men and Their Tales. New York: Schocken Books, 2003. ISBN 9780805241730.

- Wiesel, Elie. The Time of the Uprooted. New York: Knopf, 2005. ISBN 9781400041725.

- Wiesel, Elie. All Rivers Run to the Sea: Memoirs. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1995. ISBN 9780679439165.

- Wiesel, Elie. And the Sea is Never Full: Memoirs 1969-. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1999. ISBN 9780679439172.

Notes

- ↑ Elie Wiesel, Nobel Acceptance Speech, NobelPrize.org. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ↑ PBS, Speak Truth to Power, Umbrage Editions. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 PBS, The Life and Work of Wiesel. Lives and Legacies Films, Inc. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ↑ Ellen S. Fine, Legacy of Night: The Literary Universe of Elie Wiesel (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1982).

- ↑ Elie Wiesel, Night (New York: Hill and Wang, 1958, ISBN 0553272535).

- ↑ Elie Wiesel, And the Sea Is Never Full: Memoirs, 1969- (Knopf, 1999, ISBN 978-0679439172), 191.

- ↑ The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity, Create Change. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ↑ Michael Pariser, Elie Wiesel (Brookfield: The Millbrook Press, 1994), p. 43.

- ↑ The Norwegian Nobel Committee, The Nobel Peace Prize for 1986. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ↑ Alan Yuhas, Elie Wiesel, Nobel winner and Holocaust survivor, dies aged 87 The Guardian, July 2, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ↑ Ronen Shnidman, Elie Wiesel, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and renowned Holocaust survivor, dies at 87 Haaretz, July 2, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ↑ "Orrin Hatch Pays Tribute to Elie Wiesel", The Weekly Standard, July 8, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chmiel, Mark. Elie Wiesel and the Politics of Moral Leadership. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-1566398572.

- Fine, Ellen S. Legacy of Night: The Literary Universe of Elie Wiesel. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1982. ISBN 0873955900.

- Pariser, Michael. Elie Wiesel. Brookfield: The Millbrook Press, 1994. ISBN 978-1562947439

- Rittner, Carol. Elie Wiesel: Between Memory and Hope. New York: New York University Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0814774106.

- Rosenfeld, Alvin H., and Irving Greenberg. Confronting the Holocaust: The Impact of Elie Wiesel. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1978. ISBN 978-0253112903.

External links

All links retrieved February 13, 2024.

- The Life and Work of Wiesel Public Broadcasting Service.

- Elie Wiesel "The Perils of Indifference", The History Place.

- Elie Wiesel Must Respect Palestinian Memories. Media Monitors Network.

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.