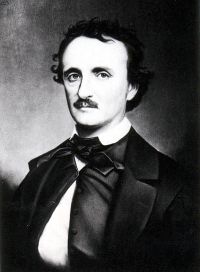

Edgar Allan Poe

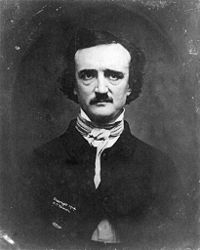

This daguerreotype of Poe was taken in 1848 when he was 39, a year before his death. | |

| Born: | January 19 1809 Boston, Massachusetts U.S. |

|---|---|

| Died: | October 7 1849 (aged 40) Baltimore, Maryland U.S. |

| Occupation(s): | Poet, short story writer, editor, literary critic |

| Literary genre: | Horror fiction, Crime fiction, Detective fiction |

| Literary movement: | Romanticism, Dark romanticism |

| Magnum opus: | The Raven |

| Influences: | Lord Byron, Charles Dickens, Ann Radcliffe, Nathaniel Hawthorne |

| Influenced: | Charles Baudelaire, Oscar Wilde, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle, Clark Ashton Smith, Jules Verne, H. P. Lovecraft, Jorge Luis Borges, Ray Bradbury, Lemony Snicket, Stefan Grabinski, Fernando Pessoa, Harlan Ellison, Ville Valo, Stephen King, Antoni Lange |

Edgar Allan Poe (January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American poet, short story writer, playwright, editor, literary critic, essayist and one of the leaders of the American Romantic Movement. Best known for his tales of mystery and of the macabre, Poe was one of the early American practitioners of the short story and a progenitor of detective fiction and crime fiction. He is also credited with contributing to the emergent science fiction genre.[1]

Born in Boston, Edgar Poe's parents died when he was still young and he was taken in by John and Frances Allan of Richmond, Virginia. Raised there and for a few years in England, the Allans raised Poe in relative wealth, though he was never formally adopted. After a short period at the University of Virginia and a brief attempt at a military career, Poe and the Allans parted ways. Poe's publishing career began humbly with an anonymous collection of poems called Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827), credited only "by a Bostonian." Poe moved to Baltimore to live with blood-relatives and switched his focus from poetry to prose. In July of 1835, he became assistant editor of the Southern Literary Messenger in Richmond, where he helped increase subscriptions and began developing his own style of literary criticism. That year he also married Virginia Clemm, his 13-year old cousin.

After an unsuccessful novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, Poe produced his first collection of short stories, Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque in 1839. That year Poe became editor of Burton's Gentlemen's Magazine and, later, Graham's Magazine in Philadelphia. It was in Philadelphia that many of his most well-known works would be published. In that city, Poe also planned on starting his own journal, The Penn (later renamed The Stylus), though it would never come to be. In February 1844, he moved to New York City and worked with the Broadway Journal, a magazine of which he would eventually become sole owner.

In January 1845, Poe published "The Raven" to instant success but, only two years later, his wife Virginia died of tuberculosis on January 30, 1847. Poe considered remarrying but never did. On October 7, 1849, Poe died at the age of 40 in Baltimore. The cause of his death is undetermined and has been attributed to alcohol, drugs, cholera, rabies, suicide (although likely to be mistaken with his suicide attempt in the previous year), tuberculosis, heart disease, brain congestion and other agents.[2]

Poe's legacy includes a significant influence in literature in the United States and around the world as well as in specialized fields like cosmology and cryptography. Additionally, Poe and his works appear throughout popular culture in literature, music, films, television, video games, etc. Some of his homes are dedicated as museums today.

Life and career

Early life

Poe was born Edgar Poe to a Scots-Irish family in Boston, Massachusetts, on January 19, 1809, the son of actress Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins Poe and actor David Poe, Jr. The second of three children, his elder brother was William Henry Leonard Poe, and younger sister, Rosalie Poe.[3] His father abandoned their family in 1810.[4] His mother died a year later from "consumption" (tuberculosis). Poe was then taken into the home of John Allan, a successful Scottish merchant in Richmond, Virginia, who dealt in a variety of goods including tobacco, cloths, wheat, tombstones, and slaves.[5] The Allans served as a foster family but never formally adopted Poe, though they gave him the name "Edgar Allan Poe."[6]

The Allan family had young Edgar baptized in the Episcopal Church in 1812. John Allan alternately spoiled and aggressively disciplined his foster son.[7] The family, including Allan's wife Frances Valentine Allan and Edgar, sailed to England in 1815. Edgar attended the Grammar School in Irvine, Scotland (where John Allan was born) for a short period in 1815, before rejoining the family in London, in 1816. He studied at a boarding school in Chelsea until summer 1817. Then he was entered at Reverend John Bransby’s Manor House School at Stoke Newington, then a suburb four miles (6 km) north of London.[8] Bransby is mentioned by name as a character in "William Wilson."

Poe moved back with the Allans to Richmond, Virginia in 1820. In 1825, John Allan's friend and business benefactor William Galt, said to be the wealthiest man in Richmond, died and left Allan several acres of real estate. The inheritance was estimated at $750,000. By summer 1825, Allan celebrated his expansive wealth by purchasing a two-story brick home named "Moldavia".[9] Poe may have become engaged to Sarah Elmira Royster before he registered at the one-year old University of Virginia in February 1826 with the intent to study languages.[10] The University, in its infancy, was established on the ideals of its founder Thomas Jefferson. It had strict rules against gambling, horses, guns, tobacco and alcohol, but these rules were generally ignored. Jefferson had enacted a system of student self-government, allowing students to choose their own studies, make their own arrangements for boarding, and report all wrongdoing to the faculty. The unique system was still in chaos and there was a high drop-out rate.[11] During his time there, Poe lost touch with Royster and also became estranged from his foster father over gambling debts. Poe claimed that Allan had not given him sufficient money to register for classes, purchase texts, and procure and furnish a dormitory. Allan did send additional money and clothes, but Poe's debts increased.[12] Poe gave up on the University after a year and, not feeling welcome in Richmond, especially when he learned that his sweetheart Royster had married Alexander Shelton, he traveled to Boston in April 1827, sustaining himself with odd jobs as a clerk and newspaper writer.[13] At some point he was using the pseudonym Henri Le Rennet.[14]

Military career

Reduced to destitution, Poe enlisted in the United States Army as a private, using the name "Edgar A. Perry" and claiming he was 22 years old (he was 18) on May 26, 1827. He first served at Fort Independence in Boston Harbor for five dollars a month.[15] That same year, he released his first book, a 40-page collection of poetry, Tamerlane and Other Poems attributed only as "by a Bostonian." Only 50 copies were printed, and the book received virtually no attention.[16] Poe's regiment was posted to Fort Moultrie in Charleston, South Carolina and traveled by ship on the brig Waltham on November 8, 1827. Poe was promoted to "artificer," an officer who prepared shells for artillery, and had his monthly pay doubled.[17] After serving for two years and attaining the rank of Sergeant Major for Artillery (the highest rank a noncommissioned officer can achieve), Poe sought to end his five-year enlistment early. He revealed his real name and his circumstances to his commanding officer, Lieutenant Howard, who would only allow Poe to be discharged if he reconciled with John Allan. Howard wrote a letter to Allan, but he was unsympathetic. Several months passed and pleas to Allan were ignored; Allan may not have written to Poe even to make him aware of his foster mother's illness. Frances Allan died on February 28, 1829 and Poe visited the day after her burial. Perhaps softened by his wife's death, John Allan agreed to support Poe's attempt to be discharged in order to receive an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point.[18]

Poe finally was discharged on April 15, 1829 after securing a replacement to finish his enlisted term for him.[19] Before entering West Point, Poe moved back to Baltimore for a time, to stay with his widowed aunt, Maria Clemm, her daughter, Virginia Eliza Clemm (Poe's first cousin), and his brother Henry. Meanwhile, Poe published his second book, Al Aaraaf Tamerlane and Minor Poems in Baltimore in 1829.

Poe traveled to West Point, and took his oath on July 1, 1830. John Allan married a second time. The marriage, and bitter quarrels with Poe over the children born to Allan out of affairs, led to the foster father finally disowning Poe. Poe decided to leave West Point by purposely getting court-martialed. On February 8, 1831, he was tried for gross neglect of duty and disobedience of orders for refusing to attend formations, classes, or church. Poe tactically pled not guilty to induce dismissal, knowing he would be found guilty.[20] He left for New York in February 1831, and released a third volume of poems, simply titled Poems. The book was financed with help from his fellow cadets at West Point, many of whom donated 75 cents to the cause, raising a total of $170. They may have been expecting verses similar to the satirical ones Poe had been writing about commanding officers.[21] Printed by Elam Bliss of New York, it was labeled as "Second Edition" and included a page saying, "To the U.S. Corps of Cadets this volume is respectfully dedicated." The book once again reprinted the long poems "Tamerlane" and "Al Aaraaf" but also six previously unpublished poems including early versions of "To Helen," "Israfel," and "The City in the Sea."[22]

Publishing career

He returned to Baltimore, to his aunt, brother and cousin, in March 1831. Henry died from tuberculosis in August 1831. Poe turned his attention to prose, and placed a few stories with a Philadelphia publication. He also began work on his only drama, Politian. The Saturday Visitor, a Baltimore paper, awarded a prize in October 1833 to his The Manuscript Found in a Bottle. The story brought him to the attention of John P. Kennedy, a Baltimorian of considerable means. He helped Poe place some of his stories, and also introduced him to Thomas W. White, editor of the Southern Literary Messenger in Richmond. Poe became assistant editor of the periodical in July 1835. Within a few weeks, he was discharged after being found drunk repeatedly. Returning to Baltimore, he secretly married Virginia, his cousin, on September 22, 1835. She was 13 at the time, though she is listed on the marriage certificate as being 21.[23]

Reinstated by White after promising good behavior, Poe went back to Richmond with Virginia and her mother, and remained at the paper until January 1837. During this period, its circulation increased from 700 to 3500.[3] He published several poems, book reviews, criticism, and stories in the paper. On May 16, 1836, he entered into marriage in Richmond with Virginia Clemm, this time in public.

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym was published and widely reviewed in 1838. In the summer of 1839, Poe became assistant editor of Burton's Gentleman's Magazine. He published a large number of articles, stories, and reviews, enhancing the reputation as a trenchant critic that he had established at the Southern Literary Messenger. Also in 1839, the collection Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque was published in two volumes. Though not a financial success, it was a milestone in the history of American literature, collecting such classic Poe tales as "The Fall of the House of Usher", "MS. Found in a Bottle", "Berenice", "Ligeia" and "William Wilson". Poe left Burton's after about a year and found a position as assistant at Graham's Magazine.

In June 1840, Poe published a prospectus announcing his intentions to start his own journal, The Stylus.[24] Originally, Poe intended to call the journal The Penn, as it would have been based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In the June 6, 1840 issue of Philadelphia's Saturday Evening Post, Poe purchased advertising space for his prospectus: "PROSPECTUS OF THE PENN MAGAZINE, A MONTHLY LITERARY JOURNAL, TO BE EDITED AND PUBLISHED IN THE CITY OF PHILADELPHIA, BY EDGAR A. POE."[25] The journal would never be produced.

The evening of January 20, 1842, Virginia broke a blood vessel while singing and playing the piano. Blood began to rush forth from her mouth. It was the first sign of consumption, now more commonly known as tuberculosis. She only partially recovered. Poe began to drink more heavily under the stress of Virginia's illness. He left Graham's and attempted to find a new position, for a time angling for a government post. He returned to New York, where he worked briefly at the Evening Mirror before becoming editor of the Broadway Journal and, later, sole owner. There he became involved in a noisy public feud with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. On January 29, 1845, his poem "The Raven" appeared in the Evening Mirror and became a popular sensation, making Poe a household name almost instantly.[26]

The Broadway Journal failed in 1846. Poe moved to a cottage in the Fordham section of The Bronx, New York. He loved the Jesuits at Fordham University and frequently strolled about its campus conversing with both students and faculty. Fordham University's bell tower even inspired him to write "The Bells." The Poe Cottage is on the southeast corner of the Grand Concourse and Kingsbridge Road, and is open to the public. Virginia died there on January 30, 1847.

Increasingly unstable after his wife's death, Poe attempted to court the poet Sarah Helen Whitman, who lived in Providence, Rhode Island. Their engagement failed, purportedly because of Poe's drinking and erratic behavior. However, there is also strong evidence that Whitman's mother intervened and did much to derail their relationship.[27] He then returned to Richmond and resumed a relationship with a childhood sweetheart, Sarah Elmira Royster.

Death

On October 3, 1849, Poe was found on the streets of Baltimore delirious and "in great distress, and... in need of immediate assistance," according to the friend who found him, Dr. John E. Snodgrass. He was taken to the Washington College Hospital, where he died early on the morning of October 7. Poe was never coherent long enough to explain how he came to be in his dire condition, and, oddly, was wearing clothes that were not his own. Poe is said to have repeatedly called out the name "Reynolds" on the night before his death. Some sources say Poe's final words were "Lord help my poor soul."[28] Poe suffered from bouts of depression and madness, and he may have attempted suicide in 1848.[29]

Poe finally died on Sunday, October 7, 1849 at 5:00 in the morning.[30] The precise cause of Poe's death is disputed and has aroused great controversy.

Griswold's "Memoir"

The day Edgar Allan Poe was buried, a long obituary appeared in the New York Tribune signed "Ludwig" which was soon published throughout the country. The piece began, "Edgar Allan Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it."[31] "Ludwig" was soon identified as Rufus Wilmot Griswold, a minor editor and anthologist who had borne a grudge against Poe since 1842. Griswold somehow became executor of Poe's literary estate and attempted to destroy his enemy's reputation after his death.

Rufus Griswold wrote a biographical "Memoir" of Poe, which he included in an 1850 volume of the collected works. Griswold depicted Poe as a depraved, drunk, drug-addled madman and included forged letters as evidence. Griswold's book was denounced by those who knew Poe well, but it became a popularly accepted one. This was due in part because it was the only full biography available and was widely reprinted, and in part because it seemed to accord with the narrative voice Poe used in much of his fiction.

The Poe Toaster

Adding to the mystery surrounding Poe's death, an unknown visitor affectionately referred to as the "Poe Toaster" has paid homage to Poe's grave every year since 1949. Though likely to have been several individuals in the more than 50 year history of this tradition, the tribute is always the same. Every January 19 in the early hours of the morning the man makes a toast of cognac to Poe's original grave marker and leaves three roses. Members of the Edgar Allan Poe Society in Baltimore have helped in protecting this tradition for decades. On August 15, 2007, Sam Porpora, a former historian at the Westminster Church in Baltimore where Poe is buried, claimed that he had started the tradition in the 1960s. The claim that the tradition began in 1949, he said, was a hoax in order to raise money and enhance the profile of the church. His story has not been confirmed,[32] and some details he has given to the press have been pointed out as factually inaccurate.[33]

Literary and artistic theory

In his essay "The Poetic Principle", Poe would argue that there is no such thing as a long poem, since the ultimate purpose of art is aesthetic, that is, its purpose is the effect it has on its audience, and this effect can only be maintained for a brief period of time (the time it takes to read a lyric poem, or watch a drama performed, or view a painting, etc.). He argued that an epic, if it has any value at all, must be actually a series of smaller pieces, each geared towards a single effect or sentiment, which "elevates the soul".

Poe associated the aesthetic aspect of art with pure ideality claiming that the mood or sentiment created by a work of art elevates the soul, and is thus a spiritual experience. In many of his short stories, artistically inclined characters (especially Roderick Usher from "The Fall of the House of Usher") are able to achieve this ideal aesthetic through fixation, and often exhibit obsessive personalities and reclusive tendencies. "The Oval Portrait" also examines fixation, but in this case the object of fixation is itself a work of art.

He championed art for art's sake (before the term itself was coined). He was consequentially an opponent of didacticism, arguing in his literary criticisms that the role of moral or ethical instruction lies outside the realm of poetry and art, which should only focus on the production of a beautiful work of art. He criticized James Russell Lowell in a review for being excessively didactic and moralistic in his writings, and argued often that a poem should be written "for a poem's sake". Since a poem's purpose is to convey a single aesthetic experience, Poe argues in his literary theory essay "The Philosophy of Composition", the ending should be written first. Poe's inspiration for this theory was Charles Dickens, who wrote to Poe in a letter dated March 6, 1842,

- Apropos of the "construction" of "Caleb Williams," do you know that Godwin wrote it backwards, — the last volume first, — and that when he had produced the hunting down of Caleb, and the catastrophe, he waited for months, casting about for a means of accounting for what he had done?[34]

Poe refers to the letter in his essay. Dickens's literary influence on Poe can also be seen in Poe's short story "The Man of the Crowd." Its depictions of urban blight owe much to Dickens and in many places purposefully echo Dickens's language.

He was a proponent and supporter of magazine literature, and felt that short stories, or "tales" as they were called in the early nineteenth century, which were usually considered "vulgar" or "low art" along with the magazines that published them, were legitimate art forms on par with the novel or epic poem. His insistence on the artistic value of the short story was influential in the short story's rise to prominence in later generations.

Poe often included elements of popular pseudosciences such as phrenology[35] and physiognomy[36] in his fiction.

Poe also focused the theme of each of his short stories on one human characteristic. For example, in "The Tell-Tale Heart", he focused on guilt, in "The Fall of the House of Usher", his focus was fear.

Much of Poe's work was allegorical, but his position on allegory was a nuanced one: "In defence of allegory, (however, or for whatever object, employed,) there is scarcely one respectable word to be said. Its best appeals are made to the fancy–that is to say, to our sense of adaptation, not of matters proper, but of matters improper for the purpose, of the real with the unreal; having never more of intelligible connection than has something with nothing, never half so much of effective affinity as has the substance for the shadow."[37] In his criticism, Poe said that meaning in literature should be an undercurrent just beneath the surface. Works with a too obvious meaning cease to be art.[38]

Legacy

Literary influence

Poe's work has inspired literature not only in the United States but throughout the world. France in particular ranks Poe very highly, in part due to early translations by Charles Baudelaire.

Poe's early detective fiction tales starring the fictitious C. Auguste Dupin laid the groundwork for future detectives in literature. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle said, "Each [of Poe's detective stories] is a root from which a whole literature has developed.... Where was the detective story until Poe breathed the breath of life into it?"[39] The Mystery Writers of America have named their awards for excellence in the genre the "Edgars." Poe's work also influenced science fiction, notably Jules Verne who wrote a sequel to Poe's novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket called The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, Le sphinx des glaces.[40] Science fiction author H. G. Wells noted that "Pym tells what a very intelligent mind could imagine about the south polar region a century ago".[41]

Even so, Poe has not received only praise. William Butler Yeats was generally critical of Poe, calling him "vulgar."[42] Transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson reacted to "The Raven" by saying, "I see nothing in it."[43] Aldous Huxley wrote that Poe's writing was the equivalent of wearing a diamond ring on every finger and that his poetry tried to be "too poetical" and "falls into vulgarity."[44]

Physics and cosmology

Eureka, an essay written in 1848, included a cosmological theory that anticipated black holes[45][46] and the big bang theory by 80 years, as well as the first plausible solution to Olbers' paradox.[47] Though described as a "prose poem" by Poe, who wished it to be considered as art, this work is a remarkable scientific and mystical essay unlike any of his other works. He wrote that he considered Eureka to be his career masterpiece.[48]

Poe eschewed the scientific method in his Eureka. He argued that he wrote from pure intuition, not the Aristotelian a priori method of axioms and syllogisms, nor the empirical method of modern science set forth by Francis Bacon. For this reason, he considered it a work of art, not science, but insisted that it was still true. Though some of his assertions have later proven to be false (such as his assertion that gravity must be the strongest force–it is actually the weakest), others have been shown to be surprisingly accurate and decades ahead of their time.

Cryptography

Poe had a keen interest in the field of cryptography. He had placed a notice of his abilities in the Philadelphia paper Alexander's Weekly (Express) Messenger, inviting submissions of ciphers, which he proceeded to solve.[49] In July 1841, Poe had published an essay called "Some Words on Secret Writing" in Graham's Magazine. Realizing the public interest in the topic, he wrote "The Gold-Bug" incorporating ciphers as part of the story.[50]

Poe's success in cryptography relied not so much on his knowledge of that field (his method was limited to the simple substitution cryptogram), as on his knowledge of the magazine and newspaper culture. His keen analytical abilities, which were so evident in his detective stories, allowed him to see that the general public was largely ignorant of the methods by which a simple substitution cryptogram can be solved, and he used this to his advantage.[51] The sensation Poe created with his cryptography stunt played a major role in popularizing cryptograms in newspapers and magazines.[52]

Poe had a long-standing influence on cryptography beyond public interest in his lifetime. William Friedman, America's foremost cryptologist, was heavily influenced by Poe.[53] Friedman's initial interest in cryptography came from reading "The Gold-Bug" as a child–interest he later put to use in deciphering Japan's PURPLE code during World War II.[54]

Imitators

|

"For my soul from out that shadow |

| — Lizzie Doten, "Streets of Baltimore", from Poems from the Inner Life, imitating "The Raven" by Edgar Allan Poe."[55] |

Like many famous artists, Poe's works have spawned legions of imitators and plagiarists.[56] One interesting trend among imitators of Poe, however, has been claims by clairvoyants or psychics to be "channelling" poems from Poe's spirit beyond the grave. One of the most notable of these was Lizzie Doten, who in 1863 published Poems from the Inner Life, in which she claimed to have "received" new compositions by Poe's spirit. The compositions were re-workings of famous Poe poems such as "The Bells", but which reflected a new, positive outlook. Poe researcher Thomas Ollive Mabbott notes that, at least compared to many other Poe imitators, Doten was not entirely without poetic talent, whether that talent was her own or "channelled" from Poe.

Poe in popular culture

Poe as a character

The historical Edgar Allan Poe has appeared as a fictionalized character, often representing the "mad genius" or "tormented artist" and exploiting his personal struggles.[57] Many such depictions also blend in with characters from his stories, suggesting Poe and his characters share identities.[58] Often, fictional depictions of Poe utilize his mystery-solving skills in such novels as The Poe Shadow by Matthew Pearl. His life is also often depicted in television and film.

Audio interpretations

- Vincent Price collaborated with actor Basil Rathbone on a collection of their readings of Poe's stories and poems.

- A double-CD organized by Hal Willner, "Closed On Account of Rabies" with poems and tales of Poe performed by artists as diverse as Christopher Walken, Marianne Faithfull, Iggy Pop and Jeff Buckley was issued in 1997.

Literature

- Author Ray Bradbury is a great admirer of Poe, and has either featured Poe as a character or alluded to Poe's stories in many of his works. Notable is Fahrenheit 451, a novel based in a world where books are banned and burned. A character in the novel memorizes Poe's short story collection Tales of Mystery and Imagination to make sure it is not lost forever.

- Robert R. McCammon wrote Ushers Passing, a sequel to Fall of the House of Usher, published in 1984.

- The comic/graphic novel "Lenore, the Cute Little Dead Girl" features a dead little girl inspired by Poe's poem "Lenore."

- Linda Fairstein's 2005 novel Entombed features a modern day serial killer obsessed with Poe. The story takes place amongst Poe's old haunts in New York.

- Writer Stephen Marlowe adapted the strange details of Poe's death into his 1995 novel The Lighthouse at the End of the World.

- Clive Cussler's 2004 novel Lost City has numerous references to Poe's works. For example, the end is similar to "The Fall of the House of Usher," during the costume party, all the guest are dressed up as characters from his works, and death and torture methods in the novel are similar to "The Pit and the Pendulum" and "The Cask of Amontillado."

- Norwegian comic Nemi has got a special page with Nemi drawings to a poem by Poe.

- The 1995 novel Nevermore, by William Hjortsberg concerns a serial killer whose murders are based on Poe's stories; the detectives are the odd couple Harry Houdini and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

- Edgar Allan Poe and members of the Poe family are featured as characters in James Reese's 2005 novel The Book of Spirits.

Music

Both classical and popular music incorporate much of Poe's works. Claude Debussy, for example, considered Poe an influence on his work and wrote an unfinished opera based on "The Fall of the House of Usher." The Alan Parsons Project turned Poe's work into a full-length concept album in the 1976 called Tales of Mystery and Imagination.

Playwrights and filmmakers

On the stage, the great dramatist George Bernard Shaw was greatly influenced by Poe's literary criticism, calling Poe "the greatest journalistic critic of his time." [59] Alfred Hitchcock declared Poe as a major inspiration, saying, "It's because I liked Edgar Allan Poe's stories so much that I began to make suspense films." [citation needed]

Actor John Astin, who performed as Gomez in the Addams Family television series, is an ardent admirer of Poe, whom he resembles, and in recent years has starred in a one-man play based on Poe's life and works, Edgar Allan Poe: Once Upon a Midnight.[60] The musical play Nevermore,[61] by Matt Conner and Grace Barnes, was inspired by Poe's poems and essays. Actor Vincent Price played in many films based on Poe's stories like The Pit and the Pendulum (1961), The Masque of the Red Death (1964), The Tomb of Ligeia (1965), and The Oblong Box (1969) among many more. There has also been talk about Marilyn Manson making movies out of three of Poe's stories.[citation needed]

Another Poe impersonator is Baltimore-native David Keltz, notable as the star actor in the annual Poe birthday celebration at Westminster Hall and Burying Ground every January.

In 2005, a reading of the Broadway-bound musical "Poe" was announced, with a book by David Kogeas and music and lyrics by David Lenchus, featuring Deven May as Edgar Allan Poe. Plans for a full production have not been announced. In early 2007, NYC composer Phill Greenland and book writer/actor Ethan Angelica announced a new Poe stage musical titled "Edgar," which uses only Poe's prose and letters as text, and Poe's poems as lyrics.[62]

Visual arts

- In the world of visual arts, Gustave Doré and Édouard Manet composed several illustrations for Poe's works.

- Edgar Allan Poe is a semi-frequent character in the webcomic Thinkin' Lincoln.

- Self Made Hero's line Eye Classics includes Nevermore a graphic novel anthology containing comic adaptations of various stories by Poe, created by a number of established British comic writers and artists.[63]

Preserved homes and museums

No childhood home of Poe is still standing, including the Allan family's Moldavia estate. However, the oldest standing home in Richmond, the Old Stone House, is in use as the Edgar Allan Poe Museum, though Poe never lived there. The collection includes many items Poe used during his time with the Allan family and also features several rare first printings of Poe works. The dorm room Poe is believed to have used while studying at the University of Virginia in 1826 is preserved and available for visits. Its upkeep is now overseen by a group of students and staff known as the Raven Society.[64]

The earliest surviving home in which Poe lived is in Baltimore, preserved as the Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum. Poe is believed to have lived in the home at the age of 23 when he first lived with Maria Clemm and Virginia (as well as his grandmother and possibly his brother William Henry Leonard Poe). It is open to the public and is also the home of the Edgar Allan Poe Society. Of the several homes that Poe, his wife Virginia, and his mother-in-law Maria rented in Philadelphia, only the last house has survived. The Spring Garden home, where the author lived in 1843-44, is today preserved by the National Park Service as the Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site. It is located on 7th and Spring Garden Streets, and is open Wednesday through Sunday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Poe's final home is also preserved as the Poe Cottage in the Bronx, New York.

Other Poe landmarks include a building in the Upper West Side where Poe temporarily lived when he first moved to New York. A plaque suggests that Poe wrote "The Raven" here. In Boston, a plaque hangs near the building where Poe was born once stood. Believed to have been located at 62 Carver Street (now Charles Street), the plaque is possibly in an incorrect location.[65][66]

Selected bibliography

Tales

|

Poetry

|

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Notes

- ↑ Stableford, Brian. "Science fiction before the genre." The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction, edited by Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn. Cambridge: Cambridge University of Press, 2003. pp 18-19.

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 256

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Allen, Hervey. Introduction to The Works of Edgar Allan Poe, P. F. Collier & Son, New York, 1927.

- ↑ Poe Chronology. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 8

- ↑ "Poe's Middle Name". Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 9

- ↑ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. Harper Perennial, 1991. p. 16-8

- ↑ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. Harper Perennial, 1991. p. 27-8

- ↑ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. Harper Perennial, 1991. p. 29-30

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 21-2

- ↑ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. Harper Perennial, 1991. 32-4

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 32

- ↑ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. Harper Perennial, 1991. p. 41

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 32

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 33-4

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 35

- ↑ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. Harper Perennial, 1991. p. 43-7

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 38

- ↑ Hecker, William J. Private Perry and Mister Poe: The West Point Poems. Louisiana State University Press, 2005. pp. 49-51

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992. pp. 50-1

- ↑ Hecker, William J. Private Perry and Mister Poe: The West Point Poems. Louisiana State University Press, 2005. pp. 53-4

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. New York: Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 85 ISBN 0815410387

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 119

- ↑ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. Harper Perennial, 1991. p. 159

- ↑ Hoffman, Daniel. Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1972. ISBN 0807123218 p. 80

- ↑ Benton, Richard P. "Friends and Enemies: Women in the Life of Edgar Allan Poe" as collected in Myths and Reality: The Mysterious Mr. Poe. Baltimore: Edgar Allan Poe Society, 1987. p. 19 ISBN 0961644915

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey: Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992: p. 255.

- ↑ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. Harper Perennial, 1991. p. 374

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey: Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992: p. 255.

- ↑ To read Griswold's full obituary, see Edgar Allan Poe obituary at Wikisource.

- ↑ Hall, Wiley "Poe Fan Takes Credit for Grave Legend", Associate Press, August 15, 2007. http://www.breitbart.com/article.php?id=2007-08-15_D8R1O6LO0&show_article=1&cat=breaking

- ↑ Associated Press, "Man Reveals Legend of Mystery Visitor to Edgar Allan Poe's Grave", August 15, 2007. http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,293413,00.html

- ↑ eapoe.org/misc/letters/t4203060.htm. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

- ↑ Edward Hungerford. "Poe and Phrenology," American Literature 1(1930): 209-31.

- ↑ Erik Grayson. "Weird Science, Weirder Unity: Phrenology and Physiognomy in Edgar Allan Poe" Mode 1 (2005): 56-77. Also online.

- ↑ www.eapoe.org/WORKS/criticism/hawthgr.html. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

- ↑ Wilbur, Richard. "The House of Poe," collected in Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays, edited by Robert Regan. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1967. p. 99

- ↑ Poe Encyclopedia p. 103

- ↑ Poe Encyclopedia p. 364

- ↑ Poe Encyclopaedia p. 372

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. New York: Cooper Square Press, 1992. ISBN 0815410387 p. 274

- ↑ Silverman, 265

- ↑ Huxley, Aldous. "Vulgarity in Literature," collected in Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays, Robert Regan, editor. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1967. p. 32

- ↑ "Edgar Allan Poe's Eureka" URL accessed August 14, 2006

- ↑ "Poe Foresees Modern Cosmologists' Black Holes and The Big Crunch" URL accessed August 14, 2006

- ↑ Wrinkles in Time by George Smoot and Keay Davidson, Harper Perennial, Reprint edition (October 1, 1994) ISBN 0-380-72044-2

- ↑ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. New York City: Cooper Square Press, 1992. ISBN 0815410387 p. 219

- ↑ starbase.trincoll.edu/~crypto/historical/poe.html. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- ↑ Rosenheim, Shawn James. The Cryptographic Imagination. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. p. 2, 6

- ↑ www.usna.edu/EnglishDept/poeperplex/cryptop.htm. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- ↑ Friedman, William F. "Edgar Allan Poe, Cryptographer" in On Poe: The Best from "American Literature". Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993. p. 40-1

- ↑ Rosenheim, Shawn James. The Cryptographic Imagination. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. p. 15

- ↑ Rosenheim, Shawn James. The Cryptographic Imagination. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. p. 146

- ↑ POEMS FROM THE INNER LIFE. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- ↑ www.eapoe.org/works/canon/poemsrjt.htm. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- ↑ Neimeyer, Mark. "Poe and Popular Culture," collected in The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0521797276 p. 209

- ↑ Gargano, James W. "The Question of Poe's Narrators," collected in Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays, edited by Robert Regan. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1967. p. 165

- ↑ Poe Encyclopaedia page 315

- ↑ www.astin-poe.com/. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ↑ signature-theatre.org/seasondescrip.htm#nevermore. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- ↑ Edgar: A New Chamber Musical

- ↑ [http://www.selfmadehero.com/classical_eye/nevermore.html Nevermore graphic novel from Self Made Hero

- ↑ ]http://www.uvaravensociety.com/ Raven Society online]

- ↑ Van Hoy, David C. "The Fall of the House of Edgar". The Boston Globe, Feb. 18, 2007

- ↑ Glenn, Joshua. The house of Poe — mystery solved! The Boston Globe April 9, 2007

General references

- Edgar Allan Poe: Poetry and Tales (Patrick F. Quinn, ed.) (Library of America, 1984) ISBN 9780940450189

- Edgar Allan Poe: Essays and Reviews (G.R. Thompson, ed.) (Library of America, 1984) ISBN 9780940450196

- Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe, Walter J. Black Inc, New York, (1927).

- Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography, Arthur Hobson Quinn, New York, Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc, (1941). ISBN 0801857309

- Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe, three volumes (I and II Tales and Sketches, III Poems), edited by Thomas Ollive Mabbott, The Belknap Press Of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England, (1978).

- The Unknown Poe, edited by Raymond Foye. City Lights, San Francisco, CA. Prefaces, Copyright by Raymond Foye, (1980).

- Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance by Kenneth Silverman. Harper Perennial, New York, NY, (1991).

- The Poe Encyclopedia by Frederick S. Frank and Anthony Magistrale. Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut and London, England, (1997). ISBN 0313277680

- The Classics of Style, by Edgar Allan Poe, et al., The American Academic Press, (2006). ISBN 0978728203

See also

- List of coupled cousins

External links

| Edgar Allan Poe Portal |

About Poe

- Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site

- Edgar Allan Poe Society in Baltimore

- Poe Museum in Richmond, Virginia

- Poe Cottage Bronx

- Edgar Allan Poe's Signature

- Poe's True Prediction about Cannibalism

- Maryland Public Television's Knowing Poe: The Literature, Life, and Times of Edgar Allan Poe in Baltimore and Beyond

- In a Sequestered Providence Churchyard Where Once Poe Walked - H. P. Lovecraft poem referencing Poe's visits to Whitman

- 1992 audio interview with Ken Silverman, author of Edgar A Poe : Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance by Don Swaim

Works

- Works by Edgar Allan Poe. Project Gutenberg

- PoeStories.com - A well organized site with summaries, quotes, and full text of Poe's short stories, a Poe timeline, and image gallery.

- Poems by Edgar Allan Poe at PoetryFoundation.org

- The Edgar Allan Poe Virtual Library

- Public domain recording of "The Raven"

- Poe Short Story Audiobooks - free download

- WorldCat Identities page for 'Poe, Edgar Allan 1809-1849'

| Works of Edgar Allan Poe |

|---|

| Poems |

|

Poetry (1824) • O, Tempora! O, Mores! (1825) • Song (1827) • Imitation (1827) • Spirits of the Dead (1827) • A Dream (1827) • Stanzas" (1827) (1827) • Tamerlane (1827) • The Lake (1827) • Evening Star (1827) • A Dream (1827) • To Margaret (1827) • The Happiest Day (1827) • To The River —— (1828) • Romance (1829) • Fairy-Land (1829) • To Science (1829) • To Isaac Lea (1829) • Al Aaraaf (1829) • An Acrostic (1829) • Elizabeth (1829) • To Helen (1831) • A Paean (1831) • The Sleeper (1831) • The City in the Sea (1831) • The Valley of Unrest (1831) • Israfel (1831) • The Coliseum (1833) • Enigma (1833) • Fanny (1833) • Serenade (1833) • Song of Triumph from Epimanes (1833) • Latin Hymn (1833) • To One in Paradise (1833) • Hymn (1835) • Politician (1835) • May Queen Ode (1836) • Spiritual Song (1836) • Bridal Ballad (1837) • To Zante (1837) • The Haunted Palace (1839) • Silence, a Sonnet (1839) • Lines on Joe Locke (1843) • The Conqueror Worm (1843) • Lenore (1843) • Eulalie (1843) • A Campaign Song (1844) • Dream-Land (1844) • Impromptu. To Kate Carol (1845) • To Frances (1845) • The Divine Right of Kings (1845) • Epigram for Wall Street (1845) • The Raven (1845) • A Valentine (1846) • Beloved Physician (1847) • An Enigma (1847) • Deep in Earth (1847) • Ulalume (1847) • Lines on Ale (1848) • To Marie Louise (1848) • Evangeline (1848) • A Dream Within A Dream (1849) • Eldorado (1849) • For Annie (1849) • The Bells (1849) • Annabel Lee (1849) • Alone (1875) |

| Tales |

| Metzengerstein (1832) • The Duc De L'Omelette (1832) • A Tale of Jerusalem (1832) • Loss of Breath (1832) • Bon-Bon (1832) • MS. Found in a Bottle (1833) • The Assignation (1834) • Berenice (1835) • Morella (1835) • Lionizing (1835) • The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall (1835) • King Pest (1835) • Shadow - A Parable (1835) • Four Beasts in One - The Homo-Cameleopard (1836) • Mystification (1837) • Silence - A Fable (1837) • Ligeia (1838) • How to Write a Blackwood Article (1838) • A Predicament (1838) • The Devil in the Belfry (1839) • The Man That Was Used Up (1839) • The Fall of the House of Usher (1839) • William Wilson (1839) • The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion (1839) • Why the Little Frenchman Wears His Hand in a Sling (1840) • The Business Man (1840) • The Man of the Crowd (1840) • The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841) • A Descent into the Maelström (1841) • The Island of the Fay (1841) • The Colloquy of Monos and Una (1841) • Never Bet the Devil Your Head (1841) • Eleonora (1841) • Three Sundays in a Week (1841) • The Oval Portrait (1842) • The Masque of the Red Death (1842) • The Landscape Garden (1842) • The Mystery of Marie Roget (1842) • The Pit and the Pendulum (1842) • The Tell-Tale Heart (1843) • The Gold-Bug (1843) • The Black Cat (1843) • Diddling (1843) • The Spectacles (1844) • A Tale of the Ragged Mountains (1844) • The Premature Burial (1844) • Mesmeric Revelation (1844) • The Oblong Box (1844) • The Angel of the Odd (1844) • Thou Art the Man (1844) • The Literary Life of Thingum Bob, Esq. (1844) • The Purloined Letter (1844) • The Thousand-and-Second Tale of Scheherazade (1845) • Some Words with a Mummy (1845) • The Power of Words (1845) • The Imp of the Perverse (1845) • The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether (1845) • The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar (1845) • The Sphinx (1846) • The Cask of Amontillado (1846) • The Domain of Arnheim (1847) • Mellonta Tauta (1849) • Hop-Frog (1849) • Von Kempelen and His Discovery (1849) • X-ing a Paragrab (1849) • Landor's Cottage (1849) |

| Other works |

| Essays: Maelzel's Chess Player (1836) • The Daguerreotype (1840) • The Philosophy of Furniture (1840) • A Few Words on Secret Writing (1841) • The Rationale of Verse (1843) • Morning on the Wissahiccon (1844) • Old English Poetry (1845) • The Philosophy of Composition (1846) • The Poetic Principle (1846) • Eureka (1848) Hoaxes: • The Balloon-Hoax (1844) Novels: The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1837) • The Journal of Julius Rodman (1840) Plays: Scenes From 'Politian' (1835) Other: The Conchologist's First Book (1839) • The Light-House (1849) |

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Poe, Edgar Allan |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | American poet, short story writer and literary critic |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 19 1809 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Boston, Massachusetts |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 7 1849 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Baltimore, Maryland |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.