Difference between revisions of "Child sacrifice" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (103 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} | ||

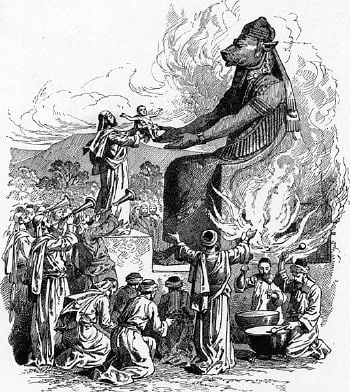

| + | [[File:Foster Bible Pictures 0074-1 Offering to Molech.jpg|thumb|350 px|Offering a child sacrifice to [[Moloch]]]] | ||

| + | '''Child sacrifice''' is the [[ritual]]istic killing of [[child]]ren in order to please or appease a [[deity]], [[supernatural]] beings, or sacred social order, tribal, group, or national loyalties in order to achieve a desired result. As such, it is a form of [[human sacrifice]]. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | While the specific rationales and occasions for offering children as sacrifices varied from culture to culture, the practice has been widespread on all the inhabited continents. Condemned throughout the world in contemporary times, nonetheless it continues illegally in certain areas. | ||

| − | [[ | + | ==Overview== |

| + | Child sacrifice was known throughout the world in historical times when people had no scientific understanding of natural phenomena, such as the weather, success of failure of crops, [[disease]], and so forth. Supernatural beings, one or many "[[god]]s," were postulated as the source of these otherwise unexplained events. The people's communication with these gods was in the form of offering sacrifices, placing items on an [[altar]] and often burning them. Such sacrifices might be crops, but often were animals or human beings who were killed in a special ritual that was intended to please or appease these gods. [[Superstitious]] beliefs that such actions would influence outcome also developed. | ||

| − | + | In many cases there appears to have been the understanding that sacrificing what is of greatest value has the greatest impact on the gods and has the greatest chance of the most favorable outcome. The case of child sacrifice is the most extreme example of offering what is most precious to the individual (the child's parents) and to the social group (the next generation being necessary for the future of the tribe or society). | |

| − | + | Some sacrifices were made on a regular basis, such as to ensure a good [[harvest]]; some were made during times of crisis, such as [[famine]] or [[flood]], to placate a possibly angry god; others were simply to affirm devotion to the god. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Numerous societies in history have practiced child sacrifice, apparently for these religious reasons. In contemporary society, where belief in gods that require such barbaric acts has been overcome, child sacrifice is no longer tolerated. Unfortunately, however, the practice does continue in some places. | ||

| + | What follows are historical examples recorded from historical cultures around the world. Countries where such ritual killing still takes place are also included. | ||

==Pre-Columbian cultures== | ==Pre-Columbian cultures== | ||

| − | The practice of [[human sacrifice]] in pre-Columbian cultures, in particular [[Mesoamerica]]n and South American cultures, is well documented both in the archaeological records and in written sources. The exact ideologies behind | + | The practice of [[human sacrifice]] in pre-Columbian cultures, in particular [[Mesoamerica]]n and South American cultures, is well documented both in the archaeological records and in written sources. The exact ideologies behind child sacrifice in different [[pre-Columbian]] cultures are unknown but it is often thought to have been performed to placate certain [[Deity|gods]]. |

===Mesoamerica=== | ===Mesoamerica=== | ||

| − | ==== | + | ====Teotihuacan culture==== |

| − | + | There is evidence of child sacrifice in [[Teotihuacan]]o culture. As early as 1906, Leopoldo Batres uncovered burials of children at the four corners of the Pyramid of the Sun. Archaeologists have found newborn skeletons associated with altars, leading some to suspect "deliberate death by infant sacrifice."<ref>Carlos Serrano Sanchez, "Funerary Practices and Human Sacrifice in Teotihuacan Burials" Kathleen Berrin and Esther Pasztory, eds., ''Teotihuacan, Art from the City of the Gods'' (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1993, ISBN 978-0500236536).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Maya culture==== | ====Maya culture==== | ||

| + | There is archaeological evidence of infant sacrifice in [[Maya]]n [[tomb]]s where the infant was buried in urns or ceramic vessels. Some Mayan art depict the extraction of children's hearts during the ascension to the throne of the new kings, or at the beginnings of the [[Maya calendar]].<ref>David Stuart, "La ideología del sacrificio entre los mayas" ''Arqueología Mexicana'' XI(63) (2003): 24–29.</ref> In one case, Stela 11 in [[Piedras Negras (Maya site)|Piedras Negras]], [[Guatemala]], a sacrificed boy can be seen. Other scenes of sacrificed boys are visible on painted jars. | ||

| − | + | In 2005 a mass grave of one- to two-year-old sacrificed children was found in the [[Maya civilization|Maya]] region of [[Comalcalco]]. The sacrifices were apparently performed for consecration purposes when building temples at the Comalcalco [[acropolis]].<ref>Carlos Marí, "Evidencian sacrificios humanos en Comalcaco: Hallan entierro de menores mayas" ''Reforma'', December 27. 2005.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In 2005 a mass grave of one- to two-year-old sacrificed children was found in the [[Maya civilization|Maya]] region of [[Comalcalco]]. The sacrifices were apparently performed for consecration purposes when building temples at the Comalcalco [[acropolis]].<ref> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Mayanist]]s believe that, like the [[Aztecs]], the Maya performed child sacrifice in specific circumstances. For example, infant sacrifice would occur to satisfy supernatural beings who would have eaten the souls of more powerful people.<ref name=Scherer>Andrew K. Scherer, ''Mortuary Landscapes of the Classic Maya: Rituals of Body and Soul'' (University of Texas Press, 2015, ISBN 978-1477300510).</ref> Infants were believed to be good offerings because they have a close connection to the [[spirit world]] through [[liminality]].<ref>Traci Ardren, ''Social Identities in the Classic Maya Northern Lowlands: Gender, Age, Memory, and Place'' (University of Texas Press, 2015, ISBN 978-1477311325).</ref> There are also skulls suggestive of child sacrifice dating to the Maya periods. It is believed that child sacrifice was preferred when there was a time of crisis such as [[famine]] or [[drought]].<ref name=Scherer/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Toltec culture==== | ====Toltec culture==== | ||

| − | In 2007, archaeologists announced that they had analyzed the remains of 24 children, aged 5 to 15, found buried together with a figurine of [[Tlaloc]]. | + | In 2007, archaeologists announced that they had analyzed the remains of 24 children, aged 5 to 15, found buried together with a figurine of [[Tlaloc]]. The children, who had been decapitated, were found near the ancient ruins of [[Tula (Mesoamerican site)|Tula]] the capital of the pre-Aztec [[Toltec]] civilization. The remains have been dated to 950 to 1150 CE. The remains are considered evidence of child sacrifice: "To try and explain why there are 24 bodies grouped in the same place, well, the only way is to think that there was a human sacrifice."<ref>Monica Medel, [https://www.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idUSN1636567520070417 Mexico finds bones suggesting Toltec child sacrifice] ''Reuters'', April 2007. Retrieved August 11, 2022. </ref> |

| − | |||

| − | "To try and explain why there are 24 bodies grouped in the same place, well, the only way is to think that there was a human sacrifice" | ||

====Aztec culture==== | ====Aztec culture==== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[File:Aztec ritual for flooding.jpg|thumb|400 px| 1499, the [[Aztecs]] performing child sacrifice to appease the angry gods who had flooded [[Tenochtitlan]]]] | [[File:Aztec ritual for flooding.jpg|thumb|400 px| 1499, the [[Aztecs]] performing child sacrifice to appease the angry gods who had flooded [[Tenochtitlan]]]] | ||

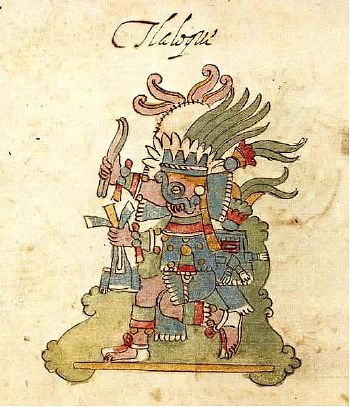

| − | [[ | + | The [[Aztec]] religion is one of the most widely documented [[pre-Hispanic]] cultures. A very important part of their annual ritual devoted to the water gods, [[Tlaloc]] and [[Chalchiuhtlicue]], included the sacrifice of infants and young children.<ref>Fray Diego Durán, ''Book of the Gods and Rites and the Ancient Calendar'' (University of Oklahoma Press, 1977, ISBN 978-0806112015).</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Archaeologist]]s have found the remains of 42 children sacrificed to [[Tlaloc]] (and a few to Ehecátl Quetzalcóatl) in the offerings of the [[Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan]]. In every case, the 42 children, mostly males aged around six, were suffering from serious cavities, abscesses, or bone infections that would have been painful enough to make them cry continually. Tlaloc required the tears of the young so their tears would wet the earth. As a result, if children did not cry, the priests would sometimes tear off the children's nails before the ritual sacrifice.<ref>Christian Duverger, ''La Flor Letal, Economia del Sacrificio Azteca'' (Fondo de cultura economica, 1993).</ref> | |

| + | [[Image:Tlaloc, Codex Rios, p.20r.JPG|thumb|right|350px|Tláloc, as shown in the late sixteenth century [[Codex Rios]].]] | ||

| + | According to [[Bernardino de Sahagún]], the Aztecs believed that if sacrifices were not given to Tlaloc the rain would not come and their crops would not grow.<ref name=Sahagun>Bernardino de Sahagún, ''Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva España I'' (Linkgua ediciones, 2021, ISBN 978-8498166873).</ref> | ||

| + | Human sacrifice was a common activity in Tenochtitlan and women and children were not exempt, as evidenced by the "tower of skulls."<ref>[https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-40473547 Aztec tower of human skulls uncovered in Mexico City] ''BBC'', July 2, 2017. Retrieved August 11, 2022.</ref> According to Sahagún, the Aztecs had a calendar for sacrifices to their different gods: | ||

| − | [[ | + | *In the month ''Atlacacauallo'' of the [[Aztec calendar]] (from February 2 to February 21 of the [[Gregorian Calendar]]) children and captives were sacrificed to the water deities, Tláloc, Chalchitlicue, and Ehécatl. |

| − | + | *In the month ''[[Tozoztontli]]'' (from March 14 to April 2) children were sacrificed to [[Coatlicue]], Tlaloc, Chalchitlicue, and Tona. | |

| + | *In the month ''[[Hueytozoztli]]'' (from April 3 to April 22) a maid, a boy, and a girl were sacrificed to Cintéotl, Chicomecacóatl, Tlaloc, and [[Quetzalcoatl]]. | ||

| + | *In the month ''[[Tepeilhuitl]]'' (from September 30 to October 19) children and two noble women were sacrificed by extraction of the heart and flaying; ritual cannibalism in honor of Tláloc-Napatecuhtli, Matlalcueye, Xochitécatl, Mayáhuel, Milnáhuatl, Napatecuhtli, Chicomecóatl, and Xochiquétzal. | ||

| + | *In the month ''[[Atemoztli]]'' (from November 29 to December 18) children and slaves were sacrificed by decapitation in honor of the Tlaloques. | ||

| − | + | He confesses he was aghast to discover that, during the first month of the year, the child sacrifices were approved by their own parents, who also ate their children.<ref name=Sahagun/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | ====Olmec culture==== |

| + | [[Image:La Venta Altar 5 (Ruben Charles).jpg|thumb|right|Altar 5 from La Venta. The inert were-jaguar baby held by the central figure is seen by some as an indication of child sacrifice. In contrast, [[:Image:Altar 5 from La Venta, left side (Ruben Charles).jpg|its sides show bas-reliefs of humans holding quite lively were-jaguar babies]]]] | ||

| − | + | Although there is no incontrovertible evidence of child sacrifice in the [[Olmec]] civilization, full skeletons of newborn or unborn infants, as well as dismembered [[femur]]s and skulls, have been found at the [[El Manatí]] sacrificial [[bog]]. These bones are associated with sacrificial offerings, particularly wooden busts. It is not known yet how the infants met their deaths.<ref>C. Ponciano Ortíz C. and María del Carmen Rodríguez, "Olmec Ritual Behavior at El Manatí: A Sacred Space" in ''Social Patterns in Pre-Classic Mesoamerica'', eds. David C. Grove and Rosemary A. Joyce. (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1999, ISBN 978-0884022527), 225-254. </ref> | |

| − | + | Some researchers have also associated infant sacrifice with Olmec ritual art showing limp "[[Olmec were-jaguar|were-jaguar]]" babies, most famously in La Venta's [[La Venta#Altars 4 & 5|Altar 5]] (to the right) or [[Las Limas Monument 1|Las Limas figure]]. Definitive answers await further findings. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===South America=== | ===South America=== | ||

| − | Archaeologists have uncovered physical evidence of child sacrifice at several pre-Columbian cultures in South America. In an early example, | + | Archaeologists have uncovered physical evidence of child sacrifice at several pre-Columbian cultures in South America. In an early example, archaeologist Steve Bourget uncovered the bones of 42 male adolescents in Northern [[Peru]] in 1995.<ref>Steve Bourget, ''Sacrifice, Violence, and Ideology Among the Moche: The Rise of Social Complexity in Ancient Peru'' (University of Texas Press, 2016, ISBN 978-1477308738).</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Chimú culture==== | ====Chimú culture==== | ||

| − | The Chimú who occupied northern Peru | + | The Chimú, who occupied northern [[Peru]] following the [[Moche]], carried out what has been claimed as the largest single example of mass child sacrifice at Huanchaco, where their chief city of Chan Chan was located. Archaeologists have found the remains of more than 140 (and more than 200 [[llama]]) skeletons from children between the ages of 6 and 15 who were sacrificed in Peru's northern coastal region.<ref>[https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-43928277 Peru child sacrifice discovery may be largest in history] ''BBC News'', April 28, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2022.</ref> Researchers have identified at least 227 individuals as sacrificial victims, including children aged between four and 14. It is believed that this mass sacrifice may have been carried out to appease deities who were supposedly bringing extreme rainfall weather conditions upon the Chimú who turned to children when the sacrifice of adults was not enough to stop torrential rain and flooding caused by El Niño.<ref>[https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-08-29/peru-child-sacrifice/11459208 Archaeologists in Peru unearth 227 bodies in the biggest-ever discovery of child sacrifice] ''Australian Broadcasting Corporation'' August 29, 2019. Retrieved August 11, 2022.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Inca culture==== | ====Inca culture==== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Capacochafig.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Male figurine for Capa Cocha rituals, [[Inca]], 1450–1540 C.E., gold, [[Dumbarton Oaks]] Museum, [[Washington, DC]].]] | |

| − | The [[Inca]] culture sacrificed children in a ritual called ''[[qhapaq hucha]]'' | + | The [[Inca]] culture sacrificed children in a ritual called ''[[qhapaq hucha]]'', the practice of [[human sacrifice]], mainly using children. The Incas performed child sacrifices during or after important events, such as the death of the [[Sapa Inca]] (emperor) or during a [[famine]]. Children were selected as sacrificial victims as they were considered to be the purest of beings. These children were also physically perfect and healthy, because they were the best the people could present to their gods. The victims may be as young as 6 and as old as 15. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Months or even years before the sacrifice pilgrimage, the children were fattened up. Their diets were those of the elite, consisting of [[maize]] and animal proteins. They were dressed in fine clothing and jewelry and escorted to [[Cusco]] to meet the emperor where a feast was held in their honor. More than 100 precious ornaments were found to be buried with these children in the burial site. | Months or even years before the sacrifice pilgrimage, the children were fattened up. Their diets were those of the elite, consisting of [[maize]] and animal proteins. They were dressed in fine clothing and jewelry and escorted to [[Cusco]] to meet the emperor where a feast was held in their honor. More than 100 precious ornaments were found to be buried with these children in the burial site. | ||

| − | The Incan high priests took the children to high mountaintops for sacrifice. As the journey was extremely long and arduous, especially so for the younger, [[coca]] leaves were fed to them to aid them in their breathing so as to allow them to reach the burial site alive. Upon reaching the burial site, the children were given an intoxicating drink to minimize pain, fear, and resistance. They were then killed either by [[strangulation]], a blow to the head, or by leaving them to lose consciousness in the extreme cold and die of exposure.<ref> | + | The Incan high priests took the children to high mountaintops for sacrifice. As the journey was extremely long and arduous, especially so for the younger ones, [[coca]] leaves were fed to them to aid them in their breathing so as to allow them to reach the burial site alive. Upon reaching the burial site, the children were given an intoxicating drink to minimize pain, fear, and resistance. They were then killed either by [[strangulation]], a blow to the head, or by leaving them to lose consciousness in the extreme cold and die of exposure.<ref> Brian Handwerk, "A 6,700 metros niños incas sacrificados quedaron congelados en el tiempo" ''National Geographic'', July 29, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2022.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Early colonial [[Spain|Spanish]] [[ | + | Early colonial [[Spain|Spanish]] [[missionaries]] wrote about this practice but only recently have archaeologists such as [[Johan Reinhard]] begun to find the bodies of these victims on [[Andes|Andean]] mountaintops, naturally [[Mummy|mummified]] due to the freezing temperatures and dry windy mountain air. |

| − | + | [[image:Llullaillaco mummies in Salta city, Argentina.jpg|thumb|350px|The maiden. Llullaillaco mummies in [[Salta province]] ([[Argentina]]).]] | |

| − | In 1995, the body of an almost entirely frozen young Inca girl (age 15), later named [[Mummy Juanita]], was discovered on [[Mount Ampato]]. Two more ice-preserved mummies, one girl (age 6) and one boy (age 8), were discovered nearby a short while later. All showed signs of alcohol and coca leaves in their system, making them fall asleep, only to be frozen to death. The boy was the only one who showed signs of resistance, due to his hands and feet being tied up. It is also speculated that he might have died from suffocation, as vomit and blood were found on his clothing. | + | In 1995, the body of an almost entirely frozen young Inca girl (age 15), later named [[Mummy Juanita]], was discovered on [[Mount Ampato]]. Two more ice-preserved mummies, one girl (age 6) and one boy (age 8), were discovered nearby a short while later. All showed signs of alcohol and coca leaves in their system, making them fall asleep, only to be frozen to death.<ref> Rebecca Morelle, [https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-23496345 Inca mummies: Child sacrifice victims fed drugs and alcohol] ''BBC'', July 13, 2013. Retrieved August 11, 2022.</ref> The boy was the only one who showed signs of resistance, due to his hands and feet being tied up. It is also speculated that he might have died from suffocation, as vomit and blood were found on his clothing. |

| − | In 1999, near [[Llullaillaco]]'s 6739 meter summit, an Argentine-Peruvian expedition found the perfectly preserved bodies of [[Children of Llullaillaco|three Inca children]], sacrificed approximately 500 years earlier, | + | In 1999, near [[Llullaillaco]]'s 6739 meter summit, an Argentine-Peruvian expedition found the perfectly preserved bodies of [[Children of Llullaillaco|three Inca children]], sacrificed approximately 500 years earlier, including a 15-year-old girl, nicknamed "La doncella" (the maiden), a seven-year-old boy, and a six-year-old girl, nicknamed "La niña del rayo" (the lightning girl). The latter's nickname reflects the fact that sometime during the 500 years on the summit, the preserved body was struck by lightning, partially burning it and some of the ceremonial artifacts. The three mummies are exhibited in rotating fashion at the Museum of High Altitude Archaeology, specially built for them in Salta, Argentina.<ref>[https://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/11/science/11mummu.html In Argentina, a Museum Unveils a Long-Frozen Maiden] ''The New York Times'', September 11, 2007. Retrieved August 11, 2022. </ref> |

| − | + | ====Timoto-Cuicas culture==== | |

| + | The [[Timoto-Cuicas]] were an indigenous people of the Americas composed primarily of two large tribes, the Timote and the Cuica, that inhabited in the Andes region of Western Venezuela. They worshiped [[idol]]s of stone and clay, built temples, and offered [[human sacrifice]]s. Until colonial times, children were sacrificed secretly in [[Laguna de Urao]], [[Mérida (state)|Mérida]]. This was chronicled by [[Juan de Castellanos]], who described the feasts and human sacrifices that were done in honour of [[Icaque]], an Andean prehispanic goddess.<ref>Luis Bastidas Valecillos, [http://www.saber.ula.ve/bitstream/123456789/18495/1/articulo3.pdf De los timoto-cuicas a la invisibilidad del indigena andino y a su diversidad cultural] ''Boletín Antropológico'' 21(59) (Septiembre-Diciembre 2003). Retrieved August 11, 2022.</ref> | ||

| − | === | + | ===North America=== |

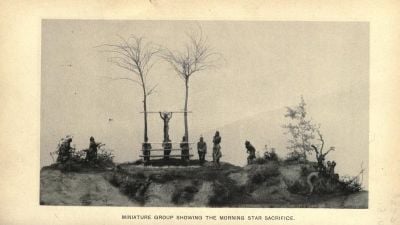

| − | + | [[File:Pawnee Sacrifice.jpg|thumb|400px|''The sacrifice to the morning star by the Skidi Pawnee'', [[Field Museum of Natural History]], Chicago]] | |

| + | The only clear example of child sacrifice in North America is the "Morning Star Ceremony" practiced by the Skidi band of the [[Pawnee]]. It was connected to the Pawnee creation narrative, in which the mating of the male Morning Star with the female Evening Star created the first human being, a girl. | ||

| − | + | For the ceremony, a young girl was captured, typically from another tribe, based on a [[dream]] by a Skidi elder. The girl was well treated for several days, and an elaborate [[scaffold]] was built for the sacrifice. When the [[morning star]] was due to rise, the girl was placed on the scaffold, and at the moment the star appeared above the horizon, the girl's chest was cut open, after which her body was shot with arrows by the men of the village, symbolically mating with her. | |

| − | + | Not all Pawnee approved of this ritual murder of an innocent child. In 1816, a Pawnee chief named [[Petalesharo]] rescued the young girl from the scaffold as the priests were about to perform the sacrifice. He accused them of cruelty and, with the support of other Pawnee warriors, was able to bring to an end this custom.<ref> Carl Waldman, ''Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes'' (New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006, ISBN 9780816062744).</ref> | |

| − | |||

==Ancient Near East== | ==Ancient Near East== | ||

===Tanakh (Hebrew Bible)=== | ===Tanakh (Hebrew Bible)=== | ||

| − | The Tanakh mentions human sacrifice in the history of [[ancient Near Eastern]] practice. | + | The [[Tanakh]] mentions [[human sacrifice]] in the history of [[ancient Near Eastern]] practice, in some cases the sacrifices were children. For example, the king of [[Moab]] gives his firstborn son and heir as a whole burnt offering (''olah'', as used of the Temple sacrifice). The Tanakh also implies that the [[Ammon (nation)|Ammonites]] offered child sacrifices to [[Moloch]],<ref>Hershel Shanks, [https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/ancient-cultures/daily-life-and-practice/first-person-human-sacrifice-to-an-ammonite-god/ First Person: Human Sacrifice to an Ammonite God?] '' Biblical Archaeology Review'' (September/October 2014). Retrieved August 12, 2022.</ref> while the prophet [[Jeremiah]] indicates that Moloch worship was practiced by Israelites in his time: "They built high places for Baal in the Valley of Ben Hinnom to sacrifice their sons and daughters to Moloch" (Jeremiah 32:35). |

====Binding of Isaac==== | ====Binding of Isaac==== | ||

{{main|Binding of Isaac}} | {{main|Binding of Isaac}} | ||

[[File:Schnorr von Carolsfeld Bibel in Bildern 1860 028.png|thumb|350px|Depiction of the [[Binding of Isaac]] by [[Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld]], 1860]] | [[File:Schnorr von Carolsfeld Bibel in Bildern 1860 028.png|thumb|350px|Depiction of the [[Binding of Isaac]] by [[Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld]], 1860]] | ||

| − | Genesis 21 relates the [[binding of Isaac]], by Abraham to present his son, [[Isaac]], as a sacrifice on [[Moriah|Mount Moriah]]. It was a test of faith (Genesis 21:12). Abraham agrees to this command without arguing. The story ends with an [[angel]] stopping Abraham at the last minute and making Isaac's sacrifice unnecessary by providing a ram, caught in some nearby bushes, to be sacrificed instead. | + | The first example of intent to offer a child sacrifice is found in Genesis 21, which relates the [[binding of Isaac]], by [[Abraham]] to present his son, [[Isaac]], as a sacrifice on [[Moriah|Mount Moriah]]. It was a test of faith (Genesis 21:12). Abraham agrees to this command without arguing. The story ends with an [[angel]] stopping Abraham at the last minute and making Isaac's sacrifice unnecessary by providing a ram, caught in some nearby bushes, to be sacrificed instead. According to Irving Greenberg, the story of the [[binding of Isaac]], symbolizes the prohibition to worship God by [[human sacrifice]], at a time when such sacrifices were the norm worldwide.<ref>Irving Greenberg, ''The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays'' (Touchstone, 1993, ISBN 978-0671873035). </ref> |

| + | |||

| + | ====Ban against child sacrifice==== | ||

| + | In Leviticus 18:21, 20:3 and Deuteronomy 12:30–31, 18:10, the [[Torah]] contains a number of imprecations against and laws forbidding child sacrifice and human sacrifice in general. The [[Tanakh]] denounces human sacrifice as barbaric customs of [[Baal]] worshipers (e.g. Psalms 106:37). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Several scholars have stated that at least some [[Israelites]] and Judahites believed child sacrifice was a legitimate religious practice. For example, [[James Kugel]] argues that the Torah's specifically forbidding child sacrifice indicates that it happened in Israel as well: | ||

| + | <blockquote>It was not just among Israel's neighbors that child sacrifice was countenanced, but apparently within Israel itself. Why else would biblical law specifically forbid such things – and with such vehemence?<ref>James Kugel, ''How to Read the Bible'' (Free Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0743235860).</ref> </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | [[Mark S. Smith]] argues that the mention of "Tophet" in Isaiah 30:27–33 indicates an acceptance of child sacrifice in the early Jerusalem practices, to which the law in Leviticus 20:2–5 forbidding child sacrifice is a response.<ref>Mark S. Smith, ''The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel'' (Eerdmans, 2002, ISBN 978-0802839725).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Susan Niditch concludes: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>"While there is considerable controversy about the matter, the consensus over the last decade concludes that child sacrifice was a part of ancient Israelite religion to large segments of Israelite communities of various periods." However, no mainstream Jewish sources allow child-sacrifice, even in theory. All mainstream Jewish sources state, or imply, that such an act is abhorrent.<ref>Susan Niditch, ''War in the Hebrew Bible: A Study in the Ethics of Violence'' (Oxford University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0195098402).</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | ====Gehenna | + | ====Gehenna==== |

| − | + | The most extensive accounts of child sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible refer to those carried out in [[Gehenna]], a fiery place where the wicked are punished after they die; a figurative equivalent for "[[Hell]]." The powerful imagery of Gehenna originates from a ancient real place known in Hebrew as גי(א)-הינום Gêhinnôm (also Guy ben-Hinnom (גיא בן הינום) meaning the Valley of Hinnom's son. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | The most extensive accounts of child sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible refer to those carried out in [[Gehenna]] | + | According to the [[Hebrew Bible]], [[pagan]]s once sacrificed their children to the idol [[Moloch]] in the fires in Gehenna. It is said that priests would bang on their drums (תופים) so that the fathers would not hear the groans of their offspring while they were consumed by fire. The [[Prophet]]s condemned such practices of child sacrifice toward Moloch, which was an abomination (2 Kings, 23:10), and they predicted the destruction of Jerusalem as a result: |

| + | <blockquote>And go out to the Valley of Ben Hinnom, near the entrance of the Potsherd Gate. There proclaim the words I tell you, and say, ‘Hear the word of the Lord, you kings of Judah and people of Jerusalem. This is what the Lord Almighty, the God of Israel, says: Listen! I am going to bring a disaster on this place that will make the ears of everyone who hears of it tingle. For they have forsaken me and made this a place of foreign gods; they have burned incense in it to gods that neither they nor their ancestors nor the kings of Judah ever knew, and they have filled this place with the blood of the innocent. They have built the high places of Baal to burn their children in the fire as offerings to Baal—something I did not command or mention, nor did it enter my mind. So beware, the days are coming, declares the Lord, when people will no longer call this place Topheth or the Valley of Ben Hinnom, but the Valley of Slaughter (Jeremiah 19:2-6).</blockquote> | ||

====Jephthah's daughter==== | ====Jephthah's daughter==== | ||

{{main|Jephthah}} | {{main|Jephthah}} | ||

[[File:Schnorr von Carolsfeld Bibel in Bildern 1860 078.png|thumb|right|350px|Jephthah sees his daughter in this 1860 woodcut by [[Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld]]]] | [[File:Schnorr von Carolsfeld Bibel in Bildern 1860 078.png|thumb|right|350px|Jephthah sees his daughter in this 1860 woodcut by [[Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld]]]] | ||

| − | + | A child sacrifice under different circumstances occurs in the [[Book of Judges]]. [[Jephthah]] makes a vow to God, saying, "If you give the Ammonites into my hands, whatever comes out of the door of my house to meet me when I return in triumph from the Ammonites will be the Lord’s, and I will sacrifice it as a burnt offering" (Judges 11:30-31). Jephthah succeeds in winning a victory, but when he returns to his home in [[Mizpah in Gilead (Judges)|Mizpah]] he sees his daughter, dancing to the sound of [[timbrel]]s, outside. | |

| + | |||

| + | After allowing her two months preparation, Judges 11:39 states that Jephthah kept his vow. This story of child sacrifice is not an order or requirement by God, but the fulfillment of an unfortunate vow made by the father. | ||

===Phoenicia and Carthage=== | ===Phoenicia and Carthage=== | ||

| − | + | Various Greek and Roman sources describe and criticize the [[Carthaginian Empire|Carthaginians]] as engaging in the practice of sacrificing children by burning.<ref>B.H. Warmington, "The Carthaginian Period" in G. Mokhtar (ed.), ''General history of Africa II: Ancient Civilizations of Africa'' (University of California Press, 1981, ISBN 978-0435948054).</ref> The practice of child sacrifice among Canaanite groups is attested by numerous sources, including: | |

| − | Various Greek and Roman sources describe and criticize the Carthaginians as engaging in the practice of sacrificing children by burning. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The practice of child sacrifice among Canaanite groups is attested by numerous sources | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Plutarch]]: | [[Plutarch]]: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>Again, would it not have been far better for the Carthaginians to have taken Critias or Diagoras to draw up their law-code at the very beginning, and so not to believe in any divine power or god, rather than to offer such sacrifices as they used to offer to Cronos? These were not in the manner that Empedocles describes in his attack on those who sacrifice living creatures: "Changed in form is the son beloved of his father so pious, who on the altar lays him and slays him. What folly!" No, but with full knowledge and understanding they themselves offered up their own children, and those who had no children would buy little ones from poor people and cut their throats as if they were so many lambs or young birds; meanwhile the mother stood by without a tear or moan; but should she utter a single moan or let fall a single tear, she had to forfeit the money, and her child was sacrificed nevertheless; and the whole area before the statue was filled with a loud noise of flutes and drums so that the cries of wailing should not reach the ears of the people.<ref> [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2008.01.0189%3Asection%3D13 Moralia 2] ''De Superstitione'' 3. Retrieved August 12, 2022.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | <blockquote> | ||

[[Plato]]: | [[Plato]]: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>With us, for instance, human sacrifice is not legal, but unholy, whereas the Carthaginians perform it as a thing they account holy and legal, and that too when some of them sacrifice even their own sons to Cronos, as I daresay you yourself have heard.<ref>Plato, [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Plat.+Minos+315c Minos 315] Retrieved August 11, 2022.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | <blockquote> | ||

| − | |||

| − | [ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Tertullian]]: | [[Tertullian]]: | ||

| + | <blockquote>In Africa infants used to be sacrificed to Saturn, and quite openly, down to the proconsulate of Tiberius, who took the priests themselves and on the very trees of their temple, under whose shadow their crimes had been committed, hung them alive like votive offerings on crosses; and the soldiers of my own country are witnesses to it, who served that proconsul in that very task. Yes, and to this day that holy crime persists in secret.<ref>Tertullian, [https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0301.htm ''Apology'' 9.2-3]. Retrieved August 12, 2022.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | <blockquote> | + | [[Cleitarchus]]: |

| + | <blockquote>And Kleitarchos says the Phoenicians, and above all the Carthaginians, venerating Kronos, whenever they were eager for a great thing to succeed, made a vow by one of their children. If they would receive the desired things, they would sacrifice it to the god. A bronze Kronos, having been erected by them, stretched out upturned hands over a bronze oven to burn the child. The flame of the burning child reached its body until, the limbs having shriveled up and the smiling mouth appearing to be almost laughing, it would slip into the oven. Therefore the grin is called “sardonic laughter,” since they die laughing."<ref>Heath Dewrell, ''Child Sacrifice in Ancient Israel'' (Eisenbrauns, 2017, ISBN 978-1575064949).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | [[ | + | ====Archaeological evidence==== |

| + | These descriptions are comparable to those found in the Hebrew Bible describing the sacrifice of children by burning to [[Baal]] and [[Moloch]] at a place called [[Tophet]]. The ancient descriptions were seemingly confirmed by the discovering of the so-called "Tophet of [[Salammbô]]" in Carthage in 1921, which contained the urns of cremated children.<ref name=Hoyos> Dexter Hoyos, ''Carthage: A Biography'' (Routledge, 2020, ISBN 978-0367635435).</ref> However, the reality and extent of child sacrifice has been debated. | ||

| + | [[File:Tunisise Carthage Tophet Salambo 02.JPG|thumb|400px|[[Stelae]] in the Tophet of Salammbó covered by a vault built in the Roman period]] | ||

| + | The specific sort of open aired sanctuary described as a Tophet in modern scholarship is unique to the Punic communities of the Western Mediterranean. The largest tophet discovered was the Tophet of Salammbô at Carthage.<ref name=Hoyos/> The Tophet of Salammbô seems to date to the city's founding and continued in use for at least a few decades after the city's destruction in 146 B.C.E. No Carthaginian texts survive that would explain or describe what rituals were performed at the tophet.<ref name=Bonnet>Corinne Bonnet, "On Gods and Earth: The Tophet and the Construction of a New identity in Punic Carthage" in Erich Stephen Gruen (ed.), ''Cultural identity in the ancient Mediterranean'' (Getty Research Institute, 2011, ISBN 978-0892369690), 373–387. </ref> | ||

| − | + | As far as the archaeological evidence reveals, the typical ritual at the Tophet began by the burial of a small urn containing a child's ashes, sometimes mixed with or replaced by that of an animal, after which a [[stele]], typically dedicated to Baal Hammon and sometimes Tanit was erected. The dead children are never mentioned on the stele inscriptions, only the dedicators and that the gods had granted them some request.<ref name=Bonnet/> | |

| − | + | The degree and existence of Carthaginian child sacrifice is controversial, and it may be impossible to determine a "definitive answer."<ref name=Hoyos/> Greek, Roman and Israelite writers refer to Phoenician child sacrifice. Excavations have been interpreted by many scholars as confirming such reports of Carthaginian child sacrifice. However, some historians have proposed that the Tophet may have been a cemetery for premature or short-lived infants who died naturally and then were ritually offered. Indeed, infant and child mortality rates were high in ancient times—with perhaps a third of Roman infants dying of natural causes in the first three centuries C.E.—which not only would explain the frequency of child burials, but would make the regular, large-scale sacrificing of children an existential threat to "communal survival."<ref name=Hoyos/> | |

| − | <blockquote> | + | ==Europe== |

| + | Sacrifices or offerings formed the chief part of the worship of the ancients. Child sacrifice is thought to be an extreme extension of the idea that the more important the object of sacrifice is to the person conducting the sacrifice, the more benefit that person will gain: | ||

| + | <blockquote>The custom of sacrificing human life to the gods arose undoubtedly from the belief, which under different forms has manifested itself at all times and in all nations, that the nobler the sacrifice and the dearer to its possessor, the more pleasing it would be to the gods. Hence the frequent instances in Grecian story of persons sacrificing their own children.<ref>Leonhard Schmitz, [https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/SMIGRA*/Sacrificium.html Sacrificium] in William Smith, ''A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities'' (London: John Murray, 1875), 998‑1000. Retrieved August 12, 2022. </ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | [[ | + | An expedition to [[Knossos]], the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on [[Crete]] and considered Europe's oldest city and the ceremonial and political center of the [[Minoan civilization]], excavated a mass grave of sacrifices that included children.<ref>Rodney Castleden, ''Minoans: Life in Bronze Age Crete'' (Routledge, 1992, ISBN 978-0415088336).</ref> Additionally, Rodney Castleden uncovered a sanctuary near Knossos where the remains of a 17-year-old were found sacrificed: |

| + | <blockquote>His ankles had evidently been tied and his legs folded up to make him fit on the table... He had been ritually murdered with the long bronze dagger engraved with a boar's head that lay beside him.<ref>Rodney Castleden, ''The Knossos Labyrinth: A New View of the "Palace of Minos" at Knossos'' (Routledge, 2011, ISBN 0415513200).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | At [[Woodhenge]], a Neolithic Class II henge and timber circle monument within the [[Stonehenge]] World Heritage Site in Wiltshire, England, a young child was found buried with its skull split by a weapon. This has been interpreted by the excavators as child sacrifice, as have other human remains.<ref>Ronald Hutton, ''The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 1993, ISBN 978-0631189466).</ref> | |

| − | [[ | + | The practice of child sacrifice in [[Europe]] as well as the [[Near East]] appears to have ended as a part of the religious transformations of [[late antiquity]].<ref>Guy Strousma, ''The End of Sacrifice: Religious Transformations in Late Antiquity'' (University of Chicago Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0226007267). </ref> |

| − | + | ==Africa== | |

| − | + | In [[Sub-Saharan Africa]], the practice of [[ritual killing]] and [[human sacrifice]] continues to take place in the twenty-first century, in contravention of the [[African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights]] and other [[International human rights instruments|human rights instruments]]. Such practices have been reported in several countries, including [[Uganda]],<ref name=Whewell>Tim Whewell, [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/newsnight/8441813.stm Witch-doctors reveal extent of child sacrifice in Uganda] ''BBC'', January 7, 2010. Retrieved August 12, 2022.</ref> [[Mozambique]],<ref>Kofi Akosah-Sarpong, [https://allafrica.com/stories/200708131401.html Mozambique tackles Witchcraft and Human Sacrifice] ''All Africa'', August 10, 2007. Retrieved August 12, 2022.</ref> and [[Mali]].<ref>Sadio Kante, [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/3663292.stm Mali's human sacrifice - myth or reality?], ''BBC'', September 20, 2004. Retrieved August 12, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | === Uganda === | |

| + | In the early twenty-first century, [[Uganda]] experienced a revival of child sacrifice. In spite of government attempts to downplay the issue, an investigation by the [[BBC]] into human sacrifice found that ritual killings of children are more common than Ugandan authorities would admit.<ref name=Whewell/> The desire for instant wealth on the part of the client and greed on the part of the witch doctor has created a ready market for children to be bought and sold at a price. Children have become a commodity of exchange and child sacrifice is more than a religious or cultural issue, it has become a commercial business.<ref name=Rogers>Chris Rogers, [https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-15255357 Where child sacrifice is a business] ''BBC News Africa'', October 11, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2022.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Rural districts near [[Kampala]], Uganda's capital, have been badly affected by [[kidnapping]]s of vulnerable people, children in particular, for sacrificial purposes. This modern phenomenon purports to be part of the country's old custom, through the use of [[Medicine#Traditional_medicine|traditional medicine]]. Witch doctors, who also identify as traditional healers, for a fee consult the spirits who communicate via them the kind of sacrifice for appeasement that is required.<ref name=Jubilee>[http://www.jubileecampaign.co.uk/stories/child-sacrifice-report Child Sacrifice in Uganda – report] ''Jubilee Campaign and Kyampisi Childcare Ministries'', 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2022. </ref> Often these sacrifices are chickens or goats, but when such sacrifices fail to make the client prosper instantly, 'the spirits' will demand human sacrifices, with child sacrifice believed to be the most powerful.<ref name=Rogers/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | When a child is sacrificed, the witch doctor and his accomplices will generally undertake the whole process, which includes the witch-hunt, the abduction, followed by the removal of certain body parts, the making of a potion and lastly, if required, the discarding of the child's body.<ref name=Jubilee/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The removal of body parts depends on the type of outcome desired. Most commonly heads, limbs, tongues, genitals, eyes, teeth, and organs are removed.<ref name=kidsrights>[https://files.kidsrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/15135225/KidsRights-Report-2014-No-Small-Sacrifice.pdf No Small Sacrifice] ''Kids Rights'', 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2022.</ref> The child is usually alive during the removal process. One type of sacrifice is the removal of blood, which is then used in medicines or mixed with herbs.<ref name=kidsrights/> It is used in the place where success, healing, or wealth is desired. In other cases a child is buried under a building foundation, either dead or alive, or only their hands, feet, and genitals to bring good luck to the new building.<ref name=Rogers/><ref name=Jubilee/> | |

| − | + | Children are victims of sacrifice for various reasons, the most common being they are relatively easy to abduct.<ref name=Jubilee/> Another reason children are abducted is that spiritually they are seen as more "pure"; a sacrifice that is "pure" or "unblemished" is believed to bring better results. If a child has been [[Circumcision|circumcised]], scarred, or has had their ears pricked, this represents disfigurement or impurity and they may be spared from sacrifice. Some parents have marked their children in these ways to protect them.<ref name=Jubilee/> | |

| − | + | Another cause for children being abducted is the belief that children represent new growing life, and offering them as a sacrifice will bring prosperity and growth to the one procuring the sacrifice.<ref> Lawrence E.Y. Mbogoni, ''Human Sacrifice and the Supernatural in African History'' (Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania: Mkuki Na Nyota Publishers, 2013, ISBN 978-9987082421).</ref> | |

| − | |||

===South Africa=== | ===South Africa=== | ||

| − | + | The continued murder of children of all ages, for body parts with which to make ''[[muti]]'', a traditional medicine practice in Southern Africa, still occurs in South Africa. "[[Muti murders]]," killing with the purpose of harvesting body parts for use in traditional | |

| − | The continued murder of | + | medicine, occur throughout South Africa, especially in rural areas. Traditional healers or witch doctors often grind up body parts and combine them with roots, herbs, seawater, animal parts, and other ingredients to prepare potions and spells for their clients.<ref>Louise Vincent, [http://www.krepublishers.com/06-Special%20Volume-Journal/S-T%20&%20T-00-Special%20Volumes/T%20&%20T-SV-02-Hlth-Nut-Problems-Web/T%20&%20T-SV-02-043-08-05-Vincent-Louise/T%20&%20T-SV-02-043-08-05-Vincent-Louise-Tt.pdf New Magic for New Times: Muti Murder in Democratic South Africa] ''Studies of Tribes and Tribals'' 2 (2008): 43-53. Retrieved August 13, 2022.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | * Ardren, Traci. ''Social Identities in the Classic Maya Northern Lowlands: Gender, Age, Memory, and Place''. University of Texas Press, 2015. ISBN 978-1477311325 | |

| + | * Berrin, Kathleen, and Esther Pasztory (eds.). ''Teotihuacan, Art from the City of the Gods''. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1993. ISBN 978-0500236536 | ||

| + | * Bourget, Steve. ''Sacrifice, Violence, and Ideology Among the Moche: The Rise of Social Complexity in Ancient Peru''. University of Texas Press, 2016. ISBN 978-1477308738 | ||

| + | * Castleden, Rodney. ''Minoans: Life in Bronze Age Crete''. Routledge, 1992. ISBN 978-0415088336 | ||

| + | * Castleden, Rodney. ''The Knossos Labyrinth: A New View of the "Palace of Minos" at Knossos''. Routledge, 2011. ISBN 0415513200 | ||

| + | * Dewrell, Heath. ''Child Sacrifice in Ancient Israel''. Eisenbrauns, 2017. ISBN 978-1575064949 | ||

| + | * Duverger, Christian. ''La Flor Letal, Economia del Sacrificio Azteca''. Fondo de cultura economica, 1993. {{ASIN|B0036BMME2}} | ||

| + | * Diego Durán, Fray. ''Book of the Gods and Rites and the Ancient Calendar''. University of Oklahoma Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0806112015 | ||

| + | * Greenberg, Irving. ''The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays''. Touchstone, 1993. ISBN 978-0671873035 | ||

| + | * Grove, David C., and Rosemary A. Joyce (eds.). ''Social Patterns in Pre-Classic Mesoamerica''. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1999. ISBN 978-0884022527 | ||

| + | * Gruen, Erich Stephen (ed.). ''Cultural identity in the ancient Mediterranean''. Getty Research Institute, 2011. ISBN 978-0892369690 | ||

| + | * Hoyos, Dexter. ''Carthage: A Biography''. Routledge, 2020. ISBN 978-0367635435 | ||

| + | * Hutton, Ronald. ''The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy''. Wiley-Blackwell, 1993. ISBN 978-0631189466 | ||

| + | * Kugel, James. ''How to Read the Bible''. Free Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0743235860 | ||

| + | * Mbogoni, Lawrence E.Y. ''Human Sacrifice and the Supernatural in African History''. Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania: Mkuki Na Nyota Publishers, 2013. ISBN 978-9987082421 | ||

| + | * Mokhtar, G. (ed.). ''General history of Africa II: Ancient Civilizations of Africa''. University of California Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0435948054 | ||

| + | * Niditch, Susan. ''War in the Hebrew Bible: A Study in the Ethics of Violence''. Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0195098402 | ||

| + | * Sahagún, Bernardino de. ''Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva España I''. Linkgua ediciones, 2021. ISBN 978-8498166873 | ||

| + | * Scherer, Andrew K. ''Mortuary Landscapes of the Classic Maya: Rituals of Body and Soul''. University of Texas Press, 2015. ISBN 978-1477300510 | ||

| + | * Smith, Mark S. ''The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel''. Eerdmans, 2002. ISBN 978-0802839725 | ||

| + | * Strousma, Guy. ''The End of Sacrifice: Religious Transformations in Late Antiquity''. University of Chicago Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0226007267 | ||

| + | * Waldman, Carl. ''Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes''. New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006. ISBN 9780816062744 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | All links retrieved | + | All links retrieved December 10, 2023. |

* [https://www.worldvision.org/blog/5-things-need-know-child-sacrifice-uganda 5 things you need to know about child sacrifice in Uganda] ''World Vision'' | * [https://www.worldvision.org/blog/5-things-need-know-child-sacrifice-uganda 5 things you need to know about child sacrifice in Uganda] ''World Vision'' | ||

| Line 314: | Line 221: | ||

[[Category:Social sciences]] | [[Category:Social sciences]] | ||

| − | {{Credits|Child_sacrifice|1097362333|Punic_religion|1103364028|Human_sacrifice_in_pre-Columbian_cultures|1080736632}} | + | {{Credits|Child_sacrifice|1097362333|Punic_religion|1103364028|Human_sacrifice_in_pre-Columbian_cultures|1080736632|Child_sacrifice_in_Uganda|1068198842}} |

Latest revision as of 15:29, 10 December 2023

Child sacrifice is the ritualistic killing of children in order to please or appease a deity, supernatural beings, or sacred social order, tribal, group, or national loyalties in order to achieve a desired result. As such, it is a form of human sacrifice.

While the specific rationales and occasions for offering children as sacrifices varied from culture to culture, the practice has been widespread on all the inhabited continents. Condemned throughout the world in contemporary times, nonetheless it continues illegally in certain areas.

Overview

Child sacrifice was known throughout the world in historical times when people had no scientific understanding of natural phenomena, such as the weather, success of failure of crops, disease, and so forth. Supernatural beings, one or many "gods," were postulated as the source of these otherwise unexplained events. The people's communication with these gods was in the form of offering sacrifices, placing items on an altar and often burning them. Such sacrifices might be crops, but often were animals or human beings who were killed in a special ritual that was intended to please or appease these gods. Superstitious beliefs that such actions would influence outcome also developed.

In many cases there appears to have been the understanding that sacrificing what is of greatest value has the greatest impact on the gods and has the greatest chance of the most favorable outcome. The case of child sacrifice is the most extreme example of offering what is most precious to the individual (the child's parents) and to the social group (the next generation being necessary for the future of the tribe or society).

Some sacrifices were made on a regular basis, such as to ensure a good harvest; some were made during times of crisis, such as famine or flood, to placate a possibly angry god; others were simply to affirm devotion to the god.

Numerous societies in history have practiced child sacrifice, apparently for these religious reasons. In contemporary society, where belief in gods that require such barbaric acts has been overcome, child sacrifice is no longer tolerated. Unfortunately, however, the practice does continue in some places.

What follows are historical examples recorded from historical cultures around the world. Countries where such ritual killing still takes place are also included.

Pre-Columbian cultures

The practice of human sacrifice in pre-Columbian cultures, in particular Mesoamerican and South American cultures, is well documented both in the archaeological records and in written sources. The exact ideologies behind child sacrifice in different pre-Columbian cultures are unknown but it is often thought to have been performed to placate certain gods.

Mesoamerica

Teotihuacan culture

There is evidence of child sacrifice in Teotihuacano culture. As early as 1906, Leopoldo Batres uncovered burials of children at the four corners of the Pyramid of the Sun. Archaeologists have found newborn skeletons associated with altars, leading some to suspect "deliberate death by infant sacrifice."[1]

Maya culture

There is archaeological evidence of infant sacrifice in Mayan tombs where the infant was buried in urns or ceramic vessels. Some Mayan art depict the extraction of children's hearts during the ascension to the throne of the new kings, or at the beginnings of the Maya calendar.[2] In one case, Stela 11 in Piedras Negras, Guatemala, a sacrificed boy can be seen. Other scenes of sacrificed boys are visible on painted jars.

In 2005 a mass grave of one- to two-year-old sacrificed children was found in the Maya region of Comalcalco. The sacrifices were apparently performed for consecration purposes when building temples at the Comalcalco acropolis.[3]

Mayanists believe that, like the Aztecs, the Maya performed child sacrifice in specific circumstances. For example, infant sacrifice would occur to satisfy supernatural beings who would have eaten the souls of more powerful people.[4] Infants were believed to be good offerings because they have a close connection to the spirit world through liminality.[5] There are also skulls suggestive of child sacrifice dating to the Maya periods. It is believed that child sacrifice was preferred when there was a time of crisis such as famine or drought.[4]

Toltec culture

In 2007, archaeologists announced that they had analyzed the remains of 24 children, aged 5 to 15, found buried together with a figurine of Tlaloc. The children, who had been decapitated, were found near the ancient ruins of Tula the capital of the pre-Aztec Toltec civilization. The remains have been dated to 950 to 1150 C.E. The remains are considered evidence of child sacrifice: "To try and explain why there are 24 bodies grouped in the same place, well, the only way is to think that there was a human sacrifice."[6]

Aztec culture

The Aztec religion is one of the most widely documented pre-Hispanic cultures. A very important part of their annual ritual devoted to the water gods, Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue, included the sacrifice of infants and young children.[7]

Archaeologists have found the remains of 42 children sacrificed to Tlaloc (and a few to Ehecátl Quetzalcóatl) in the offerings of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan. In every case, the 42 children, mostly males aged around six, were suffering from serious cavities, abscesses, or bone infections that would have been painful enough to make them cry continually. Tlaloc required the tears of the young so their tears would wet the earth. As a result, if children did not cry, the priests would sometimes tear off the children's nails before the ritual sacrifice.[8]

According to Bernardino de Sahagún, the Aztecs believed that if sacrifices were not given to Tlaloc the rain would not come and their crops would not grow.[9]

Human sacrifice was a common activity in Tenochtitlan and women and children were not exempt, as evidenced by the "tower of skulls."[10] According to Sahagún, the Aztecs had a calendar for sacrifices to their different gods:

- In the month Atlacacauallo of the Aztec calendar (from February 2 to February 21 of the Gregorian Calendar) children and captives were sacrificed to the water deities, Tláloc, Chalchitlicue, and Ehécatl.

- In the month Tozoztontli (from March 14 to April 2) children were sacrificed to Coatlicue, Tlaloc, Chalchitlicue, and Tona.

- In the month Hueytozoztli (from April 3 to April 22) a maid, a boy, and a girl were sacrificed to Cintéotl, Chicomecacóatl, Tlaloc, and Quetzalcoatl.

- In the month Tepeilhuitl (from September 30 to October 19) children and two noble women were sacrificed by extraction of the heart and flaying; ritual cannibalism in honor of Tláloc-Napatecuhtli, Matlalcueye, Xochitécatl, Mayáhuel, Milnáhuatl, Napatecuhtli, Chicomecóatl, and Xochiquétzal.

- In the month Atemoztli (from November 29 to December 18) children and slaves were sacrificed by decapitation in honor of the Tlaloques.

He confesses he was aghast to discover that, during the first month of the year, the child sacrifices were approved by their own parents, who also ate their children.[9]

Olmec culture

Although there is no incontrovertible evidence of child sacrifice in the Olmec civilization, full skeletons of newborn or unborn infants, as well as dismembered femurs and skulls, have been found at the El Manatí sacrificial bog. These bones are associated with sacrificial offerings, particularly wooden busts. It is not known yet how the infants met their deaths.[11]

Some researchers have also associated infant sacrifice with Olmec ritual art showing limp "were-jaguar" babies, most famously in La Venta's Altar 5 (to the right) or Las Limas figure. Definitive answers await further findings.

South America

Archaeologists have uncovered physical evidence of child sacrifice at several pre-Columbian cultures in South America. In an early example, archaeologist Steve Bourget uncovered the bones of 42 male adolescents in Northern Peru in 1995.[12]

Chimú culture

The Chimú, who occupied northern Peru following the Moche, carried out what has been claimed as the largest single example of mass child sacrifice at Huanchaco, where their chief city of Chan Chan was located. Archaeologists have found the remains of more than 140 (and more than 200 llama) skeletons from children between the ages of 6 and 15 who were sacrificed in Peru's northern coastal region.[13] Researchers have identified at least 227 individuals as sacrificial victims, including children aged between four and 14. It is believed that this mass sacrifice may have been carried out to appease deities who were supposedly bringing extreme rainfall weather conditions upon the Chimú who turned to children when the sacrifice of adults was not enough to stop torrential rain and flooding caused by El Niño.[14]

Inca culture

The Inca culture sacrificed children in a ritual called qhapaq hucha, the practice of human sacrifice, mainly using children. The Incas performed child sacrifices during or after important events, such as the death of the Sapa Inca (emperor) or during a famine. Children were selected as sacrificial victims as they were considered to be the purest of beings. These children were also physically perfect and healthy, because they were the best the people could present to their gods. The victims may be as young as 6 and as old as 15.

Months or even years before the sacrifice pilgrimage, the children were fattened up. Their diets were those of the elite, consisting of maize and animal proteins. They were dressed in fine clothing and jewelry and escorted to Cusco to meet the emperor where a feast was held in their honor. More than 100 precious ornaments were found to be buried with these children in the burial site.

The Incan high priests took the children to high mountaintops for sacrifice. As the journey was extremely long and arduous, especially so for the younger ones, coca leaves were fed to them to aid them in their breathing so as to allow them to reach the burial site alive. Upon reaching the burial site, the children were given an intoxicating drink to minimize pain, fear, and resistance. They were then killed either by strangulation, a blow to the head, or by leaving them to lose consciousness in the extreme cold and die of exposure.[15]

Early colonial Spanish missionaries wrote about this practice but only recently have archaeologists such as Johan Reinhard begun to find the bodies of these victims on Andean mountaintops, naturally mummified due to the freezing temperatures and dry windy mountain air.

In 1995, the body of an almost entirely frozen young Inca girl (age 15), later named Mummy Juanita, was discovered on Mount Ampato. Two more ice-preserved mummies, one girl (age 6) and one boy (age 8), were discovered nearby a short while later. All showed signs of alcohol and coca leaves in their system, making them fall asleep, only to be frozen to death.[16] The boy was the only one who showed signs of resistance, due to his hands and feet being tied up. It is also speculated that he might have died from suffocation, as vomit and blood were found on his clothing.

In 1999, near Llullaillaco's 6739 meter summit, an Argentine-Peruvian expedition found the perfectly preserved bodies of three Inca children, sacrificed approximately 500 years earlier, including a 15-year-old girl, nicknamed "La doncella" (the maiden), a seven-year-old boy, and a six-year-old girl, nicknamed "La niña del rayo" (the lightning girl). The latter's nickname reflects the fact that sometime during the 500 years on the summit, the preserved body was struck by lightning, partially burning it and some of the ceremonial artifacts. The three mummies are exhibited in rotating fashion at the Museum of High Altitude Archaeology, specially built for them in Salta, Argentina.[17]

Timoto-Cuicas culture

The Timoto-Cuicas were an indigenous people of the Americas composed primarily of two large tribes, the Timote and the Cuica, that inhabited in the Andes region of Western Venezuela. They worshiped idols of stone and clay, built temples, and offered human sacrifices. Until colonial times, children were sacrificed secretly in Laguna de Urao, Mérida. This was chronicled by Juan de Castellanos, who described the feasts and human sacrifices that were done in honour of Icaque, an Andean prehispanic goddess.[18]

North America

The only clear example of child sacrifice in North America is the "Morning Star Ceremony" practiced by the Skidi band of the Pawnee. It was connected to the Pawnee creation narrative, in which the mating of the male Morning Star with the female Evening Star created the first human being, a girl.

For the ceremony, a young girl was captured, typically from another tribe, based on a dream by a Skidi elder. The girl was well treated for several days, and an elaborate scaffold was built for the sacrifice. When the morning star was due to rise, the girl was placed on the scaffold, and at the moment the star appeared above the horizon, the girl's chest was cut open, after which her body was shot with arrows by the men of the village, symbolically mating with her.

Not all Pawnee approved of this ritual murder of an innocent child. In 1816, a Pawnee chief named Petalesharo rescued the young girl from the scaffold as the priests were about to perform the sacrifice. He accused them of cruelty and, with the support of other Pawnee warriors, was able to bring to an end this custom.[19]

Ancient Near East

Tanakh (Hebrew Bible)

The Tanakh mentions human sacrifice in the history of ancient Near Eastern practice, in some cases the sacrifices were children. For example, the king of Moab gives his firstborn son and heir as a whole burnt offering (olah, as used of the Temple sacrifice). The Tanakh also implies that the Ammonites offered child sacrifices to Moloch,[20] while the prophet Jeremiah indicates that Moloch worship was practiced by Israelites in his time: "They built high places for Baal in the Valley of Ben Hinnom to sacrifice their sons and daughters to Moloch" (Jeremiah 32:35).

Binding of Isaac

The first example of intent to offer a child sacrifice is found in Genesis 21, which relates the binding of Isaac, by Abraham to present his son, Isaac, as a sacrifice on Mount Moriah. It was a test of faith (Genesis 21:12). Abraham agrees to this command without arguing. The story ends with an angel stopping Abraham at the last minute and making Isaac's sacrifice unnecessary by providing a ram, caught in some nearby bushes, to be sacrificed instead. According to Irving Greenberg, the story of the binding of Isaac, symbolizes the prohibition to worship God by human sacrifice, at a time when such sacrifices were the norm worldwide.[21]

Ban against child sacrifice

In Leviticus 18:21, 20:3 and Deuteronomy 12:30–31, 18:10, the Torah contains a number of imprecations against and laws forbidding child sacrifice and human sacrifice in general. The Tanakh denounces human sacrifice as barbaric customs of Baal worshipers (e.g. Psalms 106:37).

Several scholars have stated that at least some Israelites and Judahites believed child sacrifice was a legitimate religious practice. For example, James Kugel argues that the Torah's specifically forbidding child sacrifice indicates that it happened in Israel as well:

It was not just among Israel's neighbors that child sacrifice was countenanced, but apparently within Israel itself. Why else would biblical law specifically forbid such things – and with such vehemence?[22]

Mark S. Smith argues that the mention of "Tophet" in Isaiah 30:27–33 indicates an acceptance of child sacrifice in the early Jerusalem practices, to which the law in Leviticus 20:2–5 forbidding child sacrifice is a response.[23]

Susan Niditch concludes:

"While there is considerable controversy about the matter, the consensus over the last decade concludes that child sacrifice was a part of ancient Israelite religion to large segments of Israelite communities of various periods." However, no mainstream Jewish sources allow child-sacrifice, even in theory. All mainstream Jewish sources state, or imply, that such an act is abhorrent.[24]

Gehenna

The most extensive accounts of child sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible refer to those carried out in Gehenna, a fiery place where the wicked are punished after they die; a figurative equivalent for "Hell." The powerful imagery of Gehenna originates from a ancient real place known in Hebrew as גי(א)-הינום Gêhinnôm (also Guy ben-Hinnom (גיא בן הינום) meaning the Valley of Hinnom's son.

According to the Hebrew Bible, pagans once sacrificed their children to the idol Moloch in the fires in Gehenna. It is said that priests would bang on their drums (תופים) so that the fathers would not hear the groans of their offspring while they were consumed by fire. The Prophets condemned such practices of child sacrifice toward Moloch, which was an abomination (2 Kings, 23:10), and they predicted the destruction of Jerusalem as a result:

And go out to the Valley of Ben Hinnom, near the entrance of the Potsherd Gate. There proclaim the words I tell you, and say, ‘Hear the word of the Lord, you kings of Judah and people of Jerusalem. This is what the Lord Almighty, the God of Israel, says: Listen! I am going to bring a disaster on this place that will make the ears of everyone who hears of it tingle. For they have forsaken me and made this a place of foreign gods; they have burned incense in it to gods that neither they nor their ancestors nor the kings of Judah ever knew, and they have filled this place with the blood of the innocent. They have built the high places of Baal to burn their children in the fire as offerings to Baal—something I did not command or mention, nor did it enter my mind. So beware, the days are coming, declares the Lord, when people will no longer call this place Topheth or the Valley of Ben Hinnom, but the Valley of Slaughter (Jeremiah 19:2-6).

Jephthah's daughter

A child sacrifice under different circumstances occurs in the Book of Judges. Jephthah makes a vow to God, saying, "If you give the Ammonites into my hands, whatever comes out of the door of my house to meet me when I return in triumph from the Ammonites will be the Lord’s, and I will sacrifice it as a burnt offering" (Judges 11:30-31). Jephthah succeeds in winning a victory, but when he returns to his home in Mizpah he sees his daughter, dancing to the sound of timbrels, outside.

After allowing her two months preparation, Judges 11:39 states that Jephthah kept his vow. This story of child sacrifice is not an order or requirement by God, but the fulfillment of an unfortunate vow made by the father.

Phoenicia and Carthage

Various Greek and Roman sources describe and criticize the Carthaginians as engaging in the practice of sacrificing children by burning.[25] The practice of child sacrifice among Canaanite groups is attested by numerous sources, including:

Again, would it not have been far better for the Carthaginians to have taken Critias or Diagoras to draw up their law-code at the very beginning, and so not to believe in any divine power or god, rather than to offer such sacrifices as they used to offer to Cronos? These were not in the manner that Empedocles describes in his attack on those who sacrifice living creatures: "Changed in form is the son beloved of his father so pious, who on the altar lays him and slays him. What folly!" No, but with full knowledge and understanding they themselves offered up their own children, and those who had no children would buy little ones from poor people and cut their throats as if they were so many lambs or young birds; meanwhile the mother stood by without a tear or moan; but should she utter a single moan or let fall a single tear, she had to forfeit the money, and her child was sacrificed nevertheless; and the whole area before the statue was filled with a loud noise of flutes and drums so that the cries of wailing should not reach the ears of the people.[26]

With us, for instance, human sacrifice is not legal, but unholy, whereas the Carthaginians perform it as a thing they account holy and legal, and that too when some of them sacrifice even their own sons to Cronos, as I daresay you yourself have heard.[27]

In Africa infants used to be sacrificed to Saturn, and quite openly, down to the proconsulate of Tiberius, who took the priests themselves and on the very trees of their temple, under whose shadow their crimes had been committed, hung them alive like votive offerings on crosses; and the soldiers of my own country are witnesses to it, who served that proconsul in that very task. Yes, and to this day that holy crime persists in secret.[28]

Cleitarchus:

And Kleitarchos says the Phoenicians, and above all the Carthaginians, venerating Kronos, whenever they were eager for a great thing to succeed, made a vow by one of their children. If they would receive the desired things, they would sacrifice it to the god. A bronze Kronos, having been erected by them, stretched out upturned hands over a bronze oven to burn the child. The flame of the burning child reached its body until, the limbs having shriveled up and the smiling mouth appearing to be almost laughing, it would slip into the oven. Therefore the grin is called “sardonic laughter,” since they die laughing."[29]

Archaeological evidence

These descriptions are comparable to those found in the Hebrew Bible describing the sacrifice of children by burning to Baal and Moloch at a place called Tophet. The ancient descriptions were seemingly confirmed by the discovering of the so-called "Tophet of Salammbô" in Carthage in 1921, which contained the urns of cremated children.[30] However, the reality and extent of child sacrifice has been debated.

The specific sort of open aired sanctuary described as a Tophet in modern scholarship is unique to the Punic communities of the Western Mediterranean. The largest tophet discovered was the Tophet of Salammbô at Carthage.[30] The Tophet of Salammbô seems to date to the city's founding and continued in use for at least a few decades after the city's destruction in 146 B.C.E. No Carthaginian texts survive that would explain or describe what rituals were performed at the tophet.[31]

As far as the archaeological evidence reveals, the typical ritual at the Tophet began by the burial of a small urn containing a child's ashes, sometimes mixed with or replaced by that of an animal, after which a stele, typically dedicated to Baal Hammon and sometimes Tanit was erected. The dead children are never mentioned on the stele inscriptions, only the dedicators and that the gods had granted them some request.[31]

The degree and existence of Carthaginian child sacrifice is controversial, and it may be impossible to determine a "definitive answer."[30] Greek, Roman and Israelite writers refer to Phoenician child sacrifice. Excavations have been interpreted by many scholars as confirming such reports of Carthaginian child sacrifice. However, some historians have proposed that the Tophet may have been a cemetery for premature or short-lived infants who died naturally and then were ritually offered. Indeed, infant and child mortality rates were high in ancient times—with perhaps a third of Roman infants dying of natural causes in the first three centuries C.E.—which not only would explain the frequency of child burials, but would make the regular, large-scale sacrificing of children an existential threat to "communal survival."[30]

Europe

Sacrifices or offerings formed the chief part of the worship of the ancients. Child sacrifice is thought to be an extreme extension of the idea that the more important the object of sacrifice is to the person conducting the sacrifice, the more benefit that person will gain:

The custom of sacrificing human life to the gods arose undoubtedly from the belief, which under different forms has manifested itself at all times and in all nations, that the nobler the sacrifice and the dearer to its possessor, the more pleasing it would be to the gods. Hence the frequent instances in Grecian story of persons sacrificing their own children.[32]

An expedition to Knossos, the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and considered Europe's oldest city and the ceremonial and political center of the Minoan civilization, excavated a mass grave of sacrifices that included children.[33] Additionally, Rodney Castleden uncovered a sanctuary near Knossos where the remains of a 17-year-old were found sacrificed:

His ankles had evidently been tied and his legs folded up to make him fit on the table... He had been ritually murdered with the long bronze dagger engraved with a boar's head that lay beside him.[34]

At Woodhenge, a Neolithic Class II henge and timber circle monument within the Stonehenge World Heritage Site in Wiltshire, England, a young child was found buried with its skull split by a weapon. This has been interpreted by the excavators as child sacrifice, as have other human remains.[35]

The practice of child sacrifice in Europe as well as the Near East appears to have ended as a part of the religious transformations of late antiquity.[36]

Africa

In Sub-Saharan Africa, the practice of ritual killing and human sacrifice continues to take place in the twenty-first century, in contravention of the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights and other human rights instruments. Such practices have been reported in several countries, including Uganda,[37] Mozambique,[38] and Mali.[39]

Uganda