Chiang Kai-shek

| |

| Names (details) | |

|---|---|

| Known in English as: | Chiang Kai-shek |

| Known in mainland China as: | 蔣介石 |

| Hanyu Pinyin: | Jiǎng Jièshí |

| Wade-Giles: | Chiang Chieh-shih |

| Known in Taiwan as: | 蔣中正 |

| Hanyu Pinyin: | Jiǎng Zhōngzhèng |

| Wade-Giles: | Chiang Chung-cheng |

| Family name: | Jiang |

| Traditional Chinese: | 蔣 |

| Simplified Chinese: | 蒋 |

| Given | names |

| Register name (譜名): | Zhoutai (周泰) |

| Milk name (乳名): | Ruiyuan (瑞元) |

| School name (學名): | Zhiqing (志清), |

| later Zhongzheng (中正) | |

| Courtesy name (字): | Jieshi (介石) |

| Kai-shek in Cantonese | |

Chiang Kai-shek (October 31, 1887 – April 5, 1975) was one of the most important political leaders in 20th century Chinese history, sandwiched between Sun Yat-sen and Mao Zedong. [1] He was a military and political leader who assumed the leadership of the Kuomintang (KMT) after the death of Sun Yat-sen in 1925. He commanded the Northern Expedition to unify China against the warlords and emerged victorious in 1928 as the overall leader of the Republic of China (ROC). Chiang led China in the Second Sino-Japanese War, during which time his international prominence grew. During the Chinese Civil War (1926–1949), Chiang attempted to eradicate the Chinese Communists but ultimately failed, forcing his government to retreat to Taiwan, where he continued serving as the President of the Republic of China and Director-General of the KMT for the remainder of his life.

Known as a zealous patriot, Chiang moved from military to political leader and back again with ease. His original goal was the modernization of China, yet the constancy of war during his tenure dictated his effectivenesss. Chiang had dreams of national glory informed by the harsh realities of his youth. Born in 1887 in a remote farm village in the eastern province of Zhejiang, he began working at the age of nine after his father died.

Like Sun Yat-sen, Chiang left an incomplete legacy. Personally ascetic, he allowed corruption to flourish. A darling of Western democrats, he imposed martial law on Taiwan (though after his 1975 death his son and successor Chiang Ching-kuo eventually lifted it). Like Sun, he tried and failed to unify a divided nation. But unlike his predecessor, Chiang Kai-shek left behind a prosperous economy that grew into a genuine democracy. [2]

Personal life

On October 31, 1887, Chiang Kai-shek was born in the town of Xikou, Fenghua County, Ningbo Prefecture, Zhejiang. However, his ancestral home (祖籍), a concept important in Chinese society, was the town of Heqiao (和橋鎮) in Jiangsu Province not far from the shores of the famous Lake Taihu).

His parents were Chiang Zhaocong (蔣肇聰) and Wang Caiyu (王采玉), part of an upper-middle class family of farmers and merchants.

Youth and Education

Chiang began attending private school at the age of 6, where he learned the Chinese classics. He lost his grandfather when he was 8 years old, and one year later he lost his father as well. He adored his mother all the more for that, describing her as the "embodiment of Confucian virtues."

In those days, fatherless families had trouble fitting into society, and were often taken advantage of. Tolerating anger and suffering, the young Chiang kindled enthusiasm for learning. He studied Chinese classics through the ages of 10 to 16. At the age of seventeen, he began attending a modern school. After that, he entered school at Ningbo, where he learned current affairs and western law. He also became interested in the revolutionary acts of Sun Yat-sen, a spark of interest that would change his life forever. [3]

Growing up in an era in which military defeats had left China destabilized and in debt, and he decided to join the military. He began his military education at the Paoting Military Academy in 1906. At eighteen, he left China to train at Tokyo's Military Preparatory Academy (Military State Academy) among soldiers whose discipline and sophistication inspired him to believe that China could one day have a modern army. [4]

There he was influenced by his compatriots to support the revolutionary movement to overthrow the Qing Dynasty and to set up a Chinese republic. He befriended fellow Zhejiang native Chen Qimei, and in 1908 Chen brought Chiang to the Revolutionary Alliance. Chiang served in the Imperial Japanese Army from 1909 to 1911.

Early Marriages

In a marriag arranged by their parents, Chiang was wed to fellow villager Mao Fumei1 (毛福梅, 1882–1939). Chiang and Mao had a son Ching-Kuo and a daughter Chien-hua. Mao died in the Second Sino-Japanese War during a bombardment.

While married to Mao, Chiang adopted two concubines:

- He married Yao Yecheng (1889-1972) in 1912. Yao raised the adopted Wei-kuo. She fled to Taiwan and died in Taipei.

- He married Chen Jieru (1906-1971) in December 1921. Chen had a daughter in 1924, named Yaoguang, who later adopted her mother's surname. Chen's autobiography disclaims the idea that she was a concubine, claiming that by the time she married Chiang, he had already been divorced from Mao, making her his wife.) Chen lived in Shanghai. She later moved to Hong Kong where she lived until her death.

Madame Chiang Kai-shek (Mayling Soong)

In 1920, Chiang met Mayling Soong, who was American-educated and a devout Christian. He was eleven years her elder, and a Buddhist. Although he was already married, Chiang proposed marriage to Mayling, much to the objection of Mayling's mother. He eventually won Mrs. Soong's blessing for marriage to her daughter by providing proof of his divorce and committing to convert to Christianity. He was baptised in 1929.

Madame Chiang Kai-shek was her husband's English translator, secretary, advisor and an influential propogandist for the Nationalist cause. She played a crucial role throughout her husband's life and public course. One example of this was in February 1943, when she became the first Chinese national, and the second woman, to ever address a joint session of the U.S. House and Senate, making the case for strong U.S. support of China in its war with Japan.

Following her husband's death in 1975 she returned to the United States, residing in Lattington, New York. Madame Chiang Kai-shek passed away on October 23, 2003, at the age of 105. [5]

Public Life

For several years, Chian Kai-shek travelled between Japan and China, furthering both his military and political training. When revolution in his homeland became evident in 1911, he returned to China where he devoted his life seeking to stabilize and develop the nation, though at times he did this from a point of exile.

Rise to power

With the outbreak of the Wuchang Uprising in 1911, Chiang Kai-shek returned to China to fight in the revolution as an artillery officer. He served in the revolutionary forces, leading a regiment in Shanghai under his friend and mentor Chen Qimei. The revolution was ultimately successful in overthrowing the Qing Dynasty and Chiang became a founding member of the Kuomintang.

After takeover of the Republican government by Yuan Shikai and the failed Second Revolution, Chiang, like his Kuomintang comrades, divided his time between exile in Japan and haven in Shanghai's foreign concession areas. In Shanghai, Chiang also cultivated ties with the criminal underworld dominated by the notorious Green Gang and its leader Du Yuesheng. In 1915 Chen Qimei, Sun Yat-sen's chief lieutenant, was assassinated by agents of Yuan Shikai and Chiang succeeded him as the leader of the Chinese Revolutionary Party in Shanghai.

In 1917 Sun Yat-sen moved his base of operations to Guangzhou and Chiang joined him the following year. Sun, who at the time was largely sidelined and without arms or money, was expelled from Guangzhou in 1918 and exiled again to Shanghai, but recovered with mercenary help in 1920. However, a rift had developed between Sun, who sought to militarily unify China under the KMT, and Guangdong Governor Chen Jiongming, who wanted to implement a federalist system with Guangdong as a model province.

On June 16, 1923, Chen attempted to expel Sun from Guangzhou and had his residence shelled. Sun and his wife Song Qingling narrowly escaped under heavy machine gun fire, only to be rescued by gunboats under the direction of Chiang Kai-shek. The incident earned Chiang Kai-shek Sun Yat-sen's lasting trust.

Sun regained control in Guangzhou in early 1924 with the help of mercenaries from Yunnan, and accepted aid from the Comintern. He then undertook a reform of the Kuomintang and established a revolutionary government aimed at unifying China under the KMT. That same year, Sun sent Chiang Kai-shek to Moscow to spend three months studying the Soviet political and military system. Chiang left his eldest son Ching-kuo in Russia, who would not return until 1937.

Chiang returned to Guangzhou and in 1924 was made Commandant of the Whampoa Military Academy. The early years at Whampoa allowed Chiang to cultivate a cadre of young officers loyal to him and by 1925 Chiang's proto-army was scoring victories against local rivals in Guangdong province. Here he also first met and worked with a young Zhou Enlai, who was selected to be Whampoa's Political Commissar. However, Chiang was deeply critical of the Kuomintang-Communist Party United Front, suspicious that the Communists would take over the KMT from within.

With Sun Yat-sen's death in 1925 a power vacuum developed in the KMT. A power struggle ensued between Chiang, who leaned towards the right wing of the KMT, and Sun Yat-sen's close comrade-in-arms Wang Jingwei, who leaned towards the left wing of the party. Though Chiang ranked relatively low in the civilian hierarchy, and Wang had succeeded Sun to power as Chairman of the National Government, Chiang's deft political maneuvering eventually allowed him to emerge victorious.

Chiang made gestures to cement himself as the successor of Sun Yat-sen. In a pairing of much political significance, on December 1 1927 Chiang married Soong May-ling, the younger sister of Soong Ching-ling, Sun Yat-sen's widow, and thus positioned himself as Sun Yat-sen's brother-in-law. In Beijing, Chiang paid homage to Sun Yat-sen and had his body moved to the capital, Nanjing, to be enshrined in the grand mausoleum.

Chiang, who became Commander-in-Chief of the National Revolutionary Forces in 1925, launched in July 1926 the Northern Expedition, a military campaign to defeat the warlords controlling northern China and unify the country under the KMT. He led the victorious Nationalist army into Hankou, Shanghai, and Nanjing.

Chiang followed Sun Yat-sen's policy of cooperation with the Chinese Communists and acceptance of Russian aid until 1927, when he dramatically reversed himself and initiated the long civil war between the Kuomintang and the Communists. On April 12, Chiang began a swift and brutal attack on thousands of suspected Communists. The communists were purged from the KMT and the Soviet advisers were expelled. This earned Chiang the support and financial backing of the Shanghai business community, and maintained him the loyalty of his Whampoa officers, many of whom hailed from Hunan elites and were discontented by the land redistribution Wang Jingwei was enacting in the area. However, this led to the beginning of the Chinese Civil War.

He established his own National Government in Nanjing, supported by his conservative allies. By the end of 1927, Chiang controlled the Kuomintang, and in 1928 he became head of the Nationalist government at Nanjing and generalissimo of all Chinese Nationalist forces. Thereafter, under various titles and offices, he exercised virtually uninterrupted power as leader of the Nationalist government. [6] The warlord capital of Beijing was taken in June 1928 and in December, the Manchurian warlord Chang Hsueh-liang pledged allegiance to Chiang's government.

"Tutelage" over China

Chiang Kai-shek gained nominal control of China, but his party was "too weak to lead and too strong to overthrow". In 1928, Chiang was named Generalissimo of all Chinese forces and Chairman of the National Government, a post he held until 1932 and later from 1943 until 1948. According to KMT political orthodoxy, this period thus began the period of "political tutelage" under the dictatorship of the Kuomintang.

The decade of 1928 to 1937 was one of consolidation and accomplishment for Chiang's government. Some of the harsh aspects of foreign concessions and privileges in China were moderated through diplomacy. The government acted energetically to modernize the legal and penal systems, stabilize prices, amortize debts, reform the banking and currency systems, build railroads and highways, improve public health facilities, legislate against narcotics-traffic in and augment industrial and agricultural production. Great strides also were made in education and, in an effort to help unify Chinese society—the New Life Movement was launched to stress Confucian moral values and personal discipline. Mandarin was promoted as a standard tongue. The widespread establishment of communications facilities further encouraged a sense of unity and pride among the people.

These successes, however, were met with constant upheavals with need of further political and military consolidation. Though much of the urban areas were now under the control of his party, the countryside still lay under the influence of severely weakened yet undefeated warlords and communists. Chiang fought with most of his warlord allies. One of these northern rebellions against the warlords Yen Hsi-shan and Feng Yuxiang in 1930 almost bankrupted the government and cost almost 250,000 casualties.

When Hu Han-min established a rival government in Guangzhou in 1931, Chiang's government was nearly toppled. A complete eradication of the Communist Party of China eluded Chiang. The Communists regrouped in Jiangxi and established the Chinese Soviet Republic. Chiang's anti-communist stance attracted the aid of German military advisers, and in Chiang's fifth campaign to defeat the Communists in 1934, he surrounded the Red Army only to see the Communists escape through the epic Long March to Yan'an.

Wartime leader of China

After Japan's invasion of Manchuria in 1931, Chiang temporarily resigned as Chairman of the National Government. Returning, he adopted a slogan "first internal pacification, then external resistance", which meant that the government would first attempt to defeat the Communists before engaging in the Japanese directly. Though it continued for several years, the policy of appeasing Japan and avoiding war was widely unpopular. In December 1936, Chiang flew to Xi'an to coordinate a major assault on Red Army forces holed up in Yan'an. On December 12, Chang Hsueh-liang whose homeland of Manchuria had been invaded by the Japanese, and several other Nationalist generals, kidnapped Chiang Kai-shek for two weeks in what is known as the Xi'an Incident. The conditions for his release included his agreement to form a "United Front" against Japan. Chiang refused to make a formal public announcement of this "United Front" as many had hoped, and his troops continued fighting the Communists throughout the war.

All-out war with Japan broke out in July 1937. In August of the same year, Chiang sent 500,000 of his best trained and equipped soldiers to defend Shanghai. With about 250,000 Chinese casualties, Chiang lost his political base of Whampoa-trained officers. Although Chiang lost militarily, the battle dispelled Japanese claims that it could conquer China in three months and demonstrated to the Western powers (which occupied parts of the city and invested heavily in it) that the Chinese would not surrender under intense Japanese fire. This was skillful diplomatic maneuvering on the part of Chiang, who knew the city would eventually fall, but wanted to make a strong gesture in order to secure Western military aid for China. By December, the capital city of Nanjing had fallen to the Japanese and Chiang moved the government inland to Chongqing. Devoid of economic and industrial resources, Chiang could not counter-attack and held off the rest of the war preserving whatever territory he still controlled, though his strategy succeeded in stretching Japanese supply lines and bogging down Japanese soldiers in the vast Chinese interior who would otherwise have been sent to conquer southeast Asia and the Pacific islands.

With the attack on Pearl Harbor and the opening of the Pacific War, China became one of the Allied Powers. During and after World War II, Chiang and his American-educated wife Soong May-ling, commonly referred to as "Madame Chiang Kai-shek", held the unwavering support of the United States China Lobby which saw in them the hope of a Christian and democratic China.

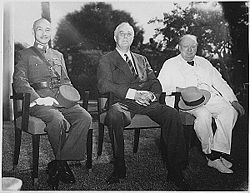

Chiang's strategy during the War opposed the strategies of both Mao Zedong and the United States. The U.S. regarded Chiang as an important ally able to help shorten the war by engaging the Japanese occupiers in China. Chiang, in contrast, used powerful associates such as H. H. Kung in Hong Kong to build the Republic of China army for certain conflict with the communist forces after the end of WWII. This fact was not understood well in the United States. The U.S. liaison officer, General Joseph Stilwell, correctly deduced that Chiang's strategy was to accumulate munitions for future civil war rather than fight the Japanese, but Stilwell was unable to convince Franklin D. Roosevelt of this and precious Lend-Lease armaments continued to be allocated to the Kuomintang. Chiang was recognized as one of the "Big Four" Allied leaders along with Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin and travelled to attend the Cairo Conference in November 1943. His wife acted as his translator and adviser.

"Losing China"

The Japanese surrender in 1945 did not bring peace to China, rather it allowed the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek and the Communists under Mao Zedong to resume their fight against each other. Chiang's Chonqing government was ill-equipped to reassert its authority in eastern China. It was able to reclaim the coastal cities with American assistance, and sometimes those of former puppet and Japanese troops, a deeply unpopular move. The countryside in the north was already largely under the control of the Communists, whose forces were better motivated and disciplined than those of the KMT.

The United States had encouraged peace talks between Chiang and Communist leader Mao Zedong in Chongqing. Distrustful of each other and of the United States' professed neutrality, they soon resorted to all-out war. The U.S. suspended aid to Chiang Kai-shek for much of the period of 1946 to 1948, in the midst of fighting against the People's Liberation Army led by Mao Zedong.

Though Chiang had achieved status abroad as a world leader, his government was deteriorating with corruption and inflation. The war had severely weakened the Nationalists both in terms of resources and popularity while the Communists were strengthened by aid from Stalin, and guerrilla organizations extending throughout rural areas. Meanwhile, high-level Kuomintang officers were growing complacent and corrupt, with an influx of Western money and military aid. Chiang sought to increase his party's strength with ties to China's wealthy landlords, alienating the peasants who represented more than 90% of the population. By the end of World War II, the communists, with their large numbers and relatively coherent ideology, were formidable rivals. [7]

Meanwhile a new Constitution promulgated in 1947, and Chiang was elected by the National Assembly to be President. This marked the beginning of the democratic constitutional government period in KMT political orthodoxy, but the Communists refused to recognize the new Constitution and its government as legitimate.

Chiang resigned as President on January 21, 1949, as KMT forces suffered massive losses against the communists. Vice President Li Tsung-jen took over as Acting President, but his relationship with Chiang soon deteriorated, as Chiang still acted as if he were in power, and Li was forced into exile in the United States. Under Chiang's direction, Li was later formally impeached by the Control Yuan.

After four years of civil war, Chiang and the nationalists were forced to flee mainland China in the early morning hours of December 10, 1949 when Communist troops laid siege to Chengdu, the last KMT occupied city in mainland China, where Chiang Kai-shek and his son Chiang Ching-kuo directed the defense at the Chengdu Central Military Academy.

They were evacuated to Tawain where they established a government-in-exile and dreamed of retaking the mainland. Chaing never again set foot on the mainland.

Presidency in Taiwan

By 1950 Chiang Kai-shek and the Nationalist government had been driven from the mainland to the island of Taiwan (Formosa) and U.S. aid had been cut off. He was elected by the National Assembly to be the President of the Republic of China on March 1, 1950. In this position he continued to claim sovereignty over all of China and until his death in 1975 he ruled "Nationalist China", developing it into an Aisan economic power.

In the context of the Cold War, most of the Western world recognized this position and the ROC represented China in the United Nations and other international organizations until the 1970s.

On Taiwan, Chiang took firm command and established a virtual dictatorship. Despite the democratic constitution, the government under Chiang was a political repressive and authoritarian single-party state, consisting almost completely of non-Taiwanese mainlanders; the "Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion" greatly enhanced executive power and the goal of "retaking the mainland" allowed the KMT to maintain its monopoly on power and to outlaw opposition parties.

Chiang's government sought to impose Chinese nationalism and repressed the local culture, such as by forbidding the use of the Taiwanese language in mass media broadcasts or in schools. The government permitted free debate within the confines of the legislature, but jailed dissidents who were either labelled as supporters of the Chinese Communist Party or of Taiwan independence.

He reorganized his military forces with the help of U.S. aid, which had resumed with the start of the Korean war, and then instituted limited democratic political reforms. Chiang continued to promise reconquest of the Chinese mainland and at times landed Nationalist guerrillas on the China coast, often to the embarrassment of the United States. Though he was one of the few leaders to send forces to Vietnam to suport the U.S. war effort, he was never able to accomplish reunification in his own homeland.

His international position was weakened considerably in 1971 when the United Nations expelled his regime and accepted the Communists as the sole legitimate government of China. [8]

Since new elections could not be held in their Communist-occupied constituencies, the members of the KMT-dominated National Assembly, held their posts indefinitely. It was under the Temporary Provisions that Chiang was able to bypass term limits to remain as president. He was reelected, unopposed by the National Assembly as president four times in 1954, 1960, 1966, and 1972.

Defeated by the Communists, Chiang purged members of the KMT previously accused of corruption, and major figures in the previous mainland government such as H.H. Kung and T.V. Soong exiled themselves to the United States. Though the government was politically authoritarian and controlled key industries, it encouraged economic development, especially in the export sector. A sweeping Land Reform Act, as well as American foreign aid during the 1950's laid the foundation for Taiwan's economic success, becoming one of the East Asian Tigers.

His son Chiang Ching-kuo and Chiang Ching-kuo's successor Lee Teng-hui would in the [1980s and 1990s increase native Taiwanese representation in the government and loosen the many authoritarian controls of the Chiang Kai-shek era.

Death and legacy

In 1975, 26 years after Chiang fled to Taiwan, he died in Taipei at the age of 87. He had suffered a major heart attack and pneumonia in the months before and died from renal failure aggravated with advanced cardiac malfunction at 23:50 on April 5.

A month of mourning was declared during which the Taiwanese people were asked to put on black armbands. Televisions ran in black-and-white while all banquets or celebrations were forbidden. On the mainland, however, Chiang's death was met with little apparent mourning and newspapers gave the brief headline "Chiang Kai-shek Has Died." Chiang's corpse was put in a copper coffin and temporarily interred at his favorite residence in Cihhu, Dasi, Taoyuan County. When his son Chiang Ching-kuo died in 1988, he was also entombed in a separate mausoleum in nearby Touliao (頭寮). The hope was to have both buried at their birthplace in Fenghua once the mainland was recovered. In 2004, Chiang Fang-liang, the widow of Chiang Ching-kuo, asked that both father and son be buried at Wuchih Mountain Military Cemetery in Sijhih, Taipei County. The state funeral ceremony is planned to take place during the spring of 2006. Chiang Fang-liang and Soong May-ling had agreed in 1997 that the former leaders be first buried but still be moved to mainland China in the event of reunification.

"Organization of the people's army", "establishment of a government of integrity" and "indemnify the rights of agricultural and industrial organizations" were slogans he used. He did not accomplish his goals of a unified and prosperous mainland China, but his leadership in Taiwan evoked loyalty and love of country in the hearts of the people. [[9]]

Chiang was succeeded as President by Vice President Yen Chia-kan and as KMT party leader by his son Chiang Ching-kuo, who retired Chiang Kai-shek's title of Director-General and instead assumed the position of Chairman.Yen Chia-kan's presidency was mainly symbolic, with real power held by Premier Chiang Ching-kuo, who became President after Yen's term ended three years later.

Chiang Kai-shek's current popularity in Taiwan is sharply divided among political lines, enjoying greater support among KMT voters and the mainlander population. However, he is largely unpopular among DPP supporters and voters. Since the democratization of the 1990s, his picture began to be removed from public buildings and currency, while many of his statues have been taken down; in sharp contrast to his son Ching-kuo and to Sun Yat-sen, his memory is rarely invoked by current political parties, including the Kuomintang.

Names

Like many other Chinese historical figures, Chiang Kai-shek used several names throughout his life. That inscribed in the genealogical records of his family is Jiang Zhoutai (蔣周泰). This so-called "register name" (譜名) is the one under which his extended relatives knew him, and the one he used in formal occasions, such as when he got married. Traditionally, the register name was not used in intercourse with people outside of the family, and in fact the concept of real or original name is not as clear-cut in China as it is in the Western world.

Traditionally, Chinese families waited a number of years before officially naming their offspring. In the meantime, they used a "milk name" (乳名), given to the infant shortly after his birth and known only to the close family. Thus, the actual name that Chiang Kai-shek received at birth was Jiang Ruiyuan (蔣瑞元).

In 1903, the 16-year-old Chiang Kai-shek went to Ningbo to be a student, and he chose a "school name" (學名). This was actually the formal name of a person, used by older people to address him, and the one he would use the most in the first decades of his life (as the person grew older, younger generations would have to use one of the courtesy names instead). (Colloquially, the school name is called "big name" (大名), whereas the "milk name" is known as the "small name" (小名).) The school name that Chiang Kai-shek chose for himself was Zhiqing (志清 - meaning "purity of intentions"). For the next fifteen years or so, Chiang Kai-shek was known as Jiang Zhiqing. This is the name under which Sun Yat-sen knew him when Chiang joined the republicans in Guangzhou in the 1910s.

In 1912, when Chiang Kai-shek was in Japan, he started to use Jiang Jieshi (蔣介石) as a pen name for the articles that he published in a Chinese magazine he founded (Voice of the Army - 軍聲). Jieshi soon became his courtesy name (字). Some think the name was chosen from the classic Chinese book the Book of Changes; other note that the first character of his courtesy name is also the first character of the courtesy name of his brother and other male relatives on the same generation line, while the second character of his courtesy name shi (石 - meaning "stone") suggests the second character of his "register name" tai (泰 - the famous Mount Tai of China). Courtesy names in China often bore a connection with the personal name of the person. As the courtesy name is the name used by people of the same generation to address the person, Chiang Kai-shek soon became known under this new name. (Jieshi is the pinyin romanization of the name, based on Mandarin, but the common romanized rendering is Kai-shek which is in Cantonese romanization. As the republicans were based in Guangzhou (a Cantonese speaking area), Chiang Kai-shek became known by Westerners under the Cantonese romanization of his courtesy name, while the family name as known in English seems to be the Mandarin pronunciation of his Chinese family name, transliterated in Wade-Giles). In mainland China, Jiang Jieshi is the name under which he is commonly known today.

Sometime in 1917 or 1918, as Chiang became close to Sun Yat-sen, he changed his name from Jiang Zhiqing to Jiang Zhongzheng (蔣中正). By adopting the name Zhongzheng ("central uprightness"), he was choosing a name very similar to the name of Sun Yat-sen, who was (and still is) known among Chinese as Zhongshan (中山 - meaning "central mountain"), thus establishing a link between the two. The meaning of uprightness, rectitude, or orthodoxy, implied by his name, also positioned him as the legitimate heir of Sun Yat-sen and his ideas. Not surprisingly, the Chinese Communists always rejected the use of this name, and it is not well known in mainland China. However, it was readily accepted by members of the Nationalist Party, and is the name under which Chiang Kai-shek is still officially known in Taiwan. Often, the name is shortened to Zhongzheng only (Chung-cheng in Wade-Giles), and passengers arriving at the Taipei airport are greeted by signs in Chinese welcoming them to the "Zhongzheng International Airport." Similarly, the largest monument in Taipei, the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall is officially in Chinese called the "Zhongzheng Memorial Hall."

His name also used to be officially written in Taiwan as "The Late President (space) Lord Chiang" (先總統 蔣公), where the one-character-wide space showed respect; this practice lost its popularity after Taiwan's democratization in the 1990s. However, he is still known as Lord Chiang (without the title or space), along with the similarly positive name Jiang Zhongzheng, in Taiwan.

Chiang was also nicknamed "the Gimo" (short for "Generalissimo") by some English-speaking foreigners, especially by Americans during the Second World War.

See also

- History of the Republic of China

- Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Song

Further reading

- Crozier, Brian. The Man Who Lost China: ISBN 068414686X

- Fenby, Jonathan. Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek and the China he lost: 2003, The Free Press, ISBN 0-7432-3144-9

- Seagrave, Sterling. The Soong Dynasty: 1996, Corgi Books, ISBN 0-552-14108-9

External links

- ROC Government Biography

- Adoption of Chiang Kai-Shek (originally surnamed Zheng) into the Chiang Family

- Order of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek supplementing the Act of Surrender by Japan on September 9 1945

- 1937 Man and Wife of the Year

- Family tree of his descendants (in Simplified Chinese)

- 1966 GIO Biographical video

- Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall

- "The Memorial Song of Late President Chiang Kai-shek" (Ministry of National Defence of ROC)

- Chiang Kai-shek Biography From Spartacus Educational

- Annals of the Flying Tigers

| Preceded by: Wang Jingwei |

Chairman of the Central Executive Committee of Kuomintang 1933–1938 |

Succeeded by: none |

| Preceded by: none (KMT headed by Committee) |

Director-General of the Kuomintang 1938–1975 |

Succeeded by: Chiang Ching-kuo (Chairman of the Kuomintang) |

| Preceded by: Tan Yankai |

Chairman of the National Government 1928–1931 |

Succeeded by: Lin Sen |

| Preceded by: T.V. Soong |

Premier of the Republic of China 1930–1931 |

Succeeded by: Chen Mingshu |

| Preceded by: Wang Jingwei |

Premier of the Republic of China 1935–1938 |

Succeeded by: H. H. Kung |

| Preceded by: H. H. Kung |

Premier of the Republic of China 1939–1945 |

Succeeded by: Song Ziwen |

| Preceded by: Lin Sen |

Chairman of the National Government 1943–1948 |

Succeeded by: none (National Government abolished) |

| Preceded by: Song Ziwen |

Premier of the Republic of China 1947 |

Succeeded by: Zhang Qun |

| Preceded by: none (position established) |

President of the Republic of China May 20, 1948–January 21, 1949 |

Succeeded by: Li Tsung-jen (acting) |

| Preceded by: Li Tsung-jen (acting) |

President of the Republic of China March 1, 1950–April 5, 1975 |

Succeeded by: Yen Chia-kan |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

zh-min-nan:Chiúⁿ Kài-se̍k bg:Чан Кай-ши cs:Čankajšek da:Chiang Kai-shek de:Chiang Kai-shek et:Jiang Jieshi es:Chiang Kai-shek eo:Jiang Jieshi fr:Tchang Kaï-chek gl:Chiang Kai Chek ko:장제스 id:Chiang Kai-shek it:Chiang Kai-shek he:צ'יאנג קאי שק hu:Csang Kaj-sek nl:Chiang Kai-shek ja:蒋介石 no:Chiang Kai-Shek pl:Chiang Kai-shek pt:Chiang Kai-shek ru:Чан Кайши sl:Čang Kaj-Šek fi:Jiang Jieshi sv:Chiang Kai-shek zh:蔣中正

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.