Book of Job

| Books of the |

The Book of Job (איוב) is one of the books of the Hebrew Bible, describing the trials of a righteous man whom God has caused to suffer. The bulk of the 42-chapter book is a dialogue between Job and his three friends concerning the problem of evil and the justice of God, in which Job insists on his innocence and his friends insist on God's justice.

The Book of Job has been called the most difficult book of the Bible. Scholars are divided as to the origin, intent, and meaning of the book. Debates also discuss whether the current prologue and epilogue of Job were originally included or were added later to provide a theological context more acceptable to Jewish tradition. Numerous commentaries on the book are classic attempts to address the issue of theodicy, or evil coexisting with God. It is ranked among the most noble books in literature. Alfred Lord Tennyson called it "the greatest poem of ancient or modern times."

Summary

Prolog

Job, a man of great wealth living in the Land of Uz, is described by the narrator as an exemplary person of righteousness: "blameless and upright; he feared God and shunned evil." (1:2) Job has seven sons and three daughters and is respected by all people on both sides of the Euphrates.

One day, the angels—among them Satan—present themselves to God, who boasts of Job's goodness. Satan replies that Job is only good because God blesses and protects him. "Stretch out your hand and strike everything he has," Satan declares, "and he will surely curse you to your face."

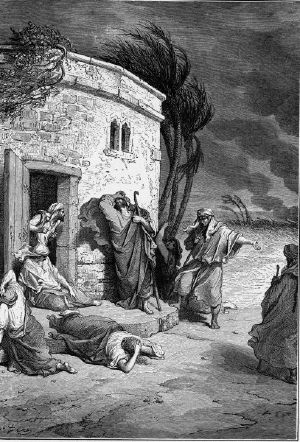

God takes Satan up on the wager and permits him to put the virtue of Job to the test. God gives Satan power over the Job's property, his slaves, and even his children. Satan then destroys all of Job's riches, his livestock, his house, his servants, and finally his sons and daughters, who are slain in a series of seeminly natural disasters.

Job mourns deeply at these horrible misfortunes. He rends his clothes, shaves his head. But he still refuses to blame God, saying, "Naked I came from my mother's womb, and naked shall I return there. The Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; Blessed be the name of the Lord." (1:20-22)

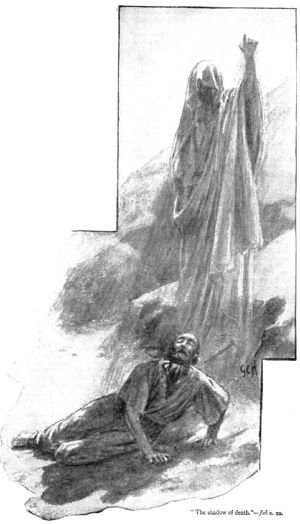

Satan then solicits God's permission to afflict Job's person as well, and God says, "Behold he is in your hand, but don’t touch his life." Satan smites Job with dreadful boils, so that Job can do nothing but sit in pain all day. Job becomes the picture of dejection as he sits on an ashpile scraping away dead skin from his body with a shard of pottery. His wife even advises him: "curse God, and die." But Job answers, "Shall we receive good at the hand of God, and shall we not receive evil?"

The dialog

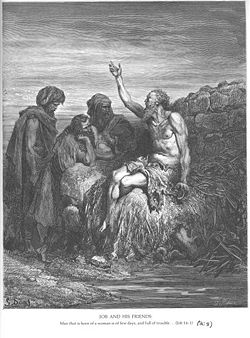

In the meantime, three of Job's friends come to visit him in his misfortune—Eliphaz the Temanite, Bildad the Shuhite, and Zophar the Naamathite. A fourth, the young Elihu the Buzite, joins the dialogue later. The three friends spend a week sitting on the ground with Job, without speaking, until Job at last breaks his silence. When he does so, his attitude has changed dramatically. Now apparently fully in touch with his feelings, Job no longer blesses God and pretends to accept his fate. Instead, "Job opened his mouth and cursed the day of his birth."

- Why is life given to a man whose way is hidden, whom God has hedged in?

- For sighing comes to me instead of food; my groans pour out like water.

- What I feared has come upon me; what I dreaded has happened to me. (3:23-25)

Job's friend Eliphaz responds to Job expression of his anguish with pious proverbs. He harshly scolds Job for not realizing that God is chastizing him: "Blessed is the man whom God corrects," he reminds Job, "so do not despise the discipline of the Almighty." (5:17)

Job, however, insists on what we have already been told. He has done no wrong, and yet, "The arrows of the Almighty are in me, my spirit drinks in their poison; God's terrors are marshaled against me." (6:4)

Bildad the Shuhite enters the argument at this point in defense of God. "Your words are a blustering wind," he chides poor Job. "Does God pervert justice? Does the Almighty pervert what is right?" Job is quick to agree that God is indeed all-powerful. This is one point on which all the dialog partners are unanimous. "He is the Maker of the Bear and Orion," decalres Job, "the Pleiades and the constellations of the south."

Where Job differs from his companions is on the question of God's goodness and justice. His friends claim that God always rewards the good and punishes the evil, but Job knows from his own experience that it is not that simple. "He destroys both the blameless and the wicked," Job insists. "When a scourge brings sudden death, he mocks the despair of the innocent. When a land falls into the hands of the wicked, he blindfolds its judges. If it is not he, then who is it?" (9:22:24)

Next, Zophar the Naamathite enters the discussion. He accuses Job of mocking God, urging Job to admit his sin and repent. "If you put away the sin that is in your hand and allow no evil to dwell in your tent," he counsels, "then you will lift up your face without shame; you will stand firm and without fear." But Job refuses to admit he is guilty when he knows he is not, saying, "I desire to speak to the Almighty and to argue my case with God." (13:3)

And so the debate continues through several more rounds. Job's friends attempt to convince him that he must be wrong, for God would not punish an innocent man. Job insists on his integrity, arguing that God has done him wrong. Both Job and his friends express God's attributes of power and sovereignty in majestic poetic images that rank among the greatest in all of literature. But they remain at loggerheads as to whether God has done right to cause Job to suffer.

Finally, the relatively young Elihu, who has not been previously introduced, speaks. He become "very angry with Job for justifying himself rather than God." But he is also angry with the three friends, "because they had found no way to refute Job." Speaking with the confidence of youth, Elihu claims for himself a prophet's wisdom and condemns all of those who have spoken previously. In his defense of God, however, he seems to offer little new, echoing Job's other friends in declaring, "It is unthinkable that God would do wrong, that the Almighty would pervert justice." What is novel in Elihu's approach is that it underscores the idea that Job's position is flawed because Job presumes that human moral standards can be imposed upon God. In Elihu's opinion, therefore, "Job opens his mouth with empty talk; without knowledge he multiplies words."

God's response

In the thirty-eighth chapter of the Book of Job, God finally breaks His silence. Dramatically speaking to Job from a whirlwind, Yahweh declares His absolute power and sovereignty over the the entire creation, including specifically Job. He does not directly accuse Job of sin, or blame Satan for Job's ills, but takes full responsibility for all that is. Making sure that Job understands his place, he asks: "Do you have an arm like God's, and can your voice thunder like his?" In almost sarcastic tones, God demands:

- Where were you when I laid the earth's foundation? Tell me, if you understand.

- Who marked off its dimensions? Surely you know!

- Who stretched a measuring line across it?

- On what were its footings set, or who laid its cornerstone—

- While the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy? (38:4-7)

God describes in detail the remarkable creatures that He created along with Job, in a world filled with both majesty and violence. "Do you hunt the prey for the lioness and satisfy the hunger of the lions when they crouch in their dens or lie in wait in a thicket?" he asks (38:39-40). God thus assumes complete responsibility for what the philosophers call "natural evil." Even mythically evil creatures are His to command:

- Can you pull in the Leviathan with a fishhook

- or tie down his tongue with a rope?

- No one is fierce enough to rouse him.

- Who then is able to stand against me?

- Who has a claim against me that I must pay?

- Everything under heaven belongs to me. (41:1-11)

Job's reply and epilogue

Whatever the merits of God's arguments, His mere presence and authority is enough to chance Job completely. "My ears had heard of you but now my eyes have seen you," Job admits. "Therefore I despise myself and repent in dust and ashes."

Yet, inexplicably, God sides with Job condemns his three friends because "you have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has." He appoints Job as their priest, commanding each of them to bring Job seven bulls and seven rams as a burnt offering. Soon, God restores Job completely, giving him double the riches he before possessed, including ten new children to replace those Satan had earlier murdered under God's authority. Job's daughters are the most beautiful in the land, and are given inheritance while Job is still alive. Job is crowned with a holy life and "died, old and full of years."

Job and the problem of Evil

The basic theme of the Book of Job is the question of theodicy: how does God relate to the reality of evil. While there are several ways to deal with this crucial philosophical problem, Job focuses on basically two possibilities. Since all parties in the dialog affirm that God is all-powerful, either God must be just, or He must not be just. The book does not deal with the possibility that God does not exist or that God is not all-powerful.

In the end, the basic question of God's justice is not clearly answered. God appears and asserts His absolute sovereignty, and Job repents. One would think from this outcome that Job's fiends were in the right: Job had sinned, and only the appearance of God brings him to the admission of this. Or possibly Job did not sin earlier, but he sinned for challenging God's justice. Yet God affirms quite the opposite, namely that Job has spoken "what is right concerning me," while Job's friends have spoken wrongly. Whether inentional or not, this resolution is a brilliant literary device, but rather than answering the issue for the reader, it serves to make the essential paradox of the book more intense.

The framing story complicates the book further: in the introductory section, God allows Satan to inflict misery on the righteous Job and his family. The conclusion has God restoring Job to wealth and granting him new children. How God could allow Satan to treat Job this way remains a subject of intense debate. It should also be noted that while the traditional Christian perspective affirms Satan to be the Devil, in the Book of Job he is presented as "the satan" (ha-satan, 'the adversary'), not Satan as a personal name. He appears as the adversary not of God, but of man, whose faith he is employed by God to test.

Job is one of the most discussed books in all of literature. Among the well known works devoted to its exegesis are:

- Carl Jung, "Answer to Job".

- Harold Kushner, "When Bad Things Happen to Good People"

- C.S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain

- Henry M. Morris, "The Remarkable Record of Job"

- James Morrow, "Blameless in Abaddon"

- Neil Simon, God's Favorite

- Elie Wiesel, "Night"

- Archibald MacLeish, J.B.

- Viktor Frankl, Man's Search for Meaning

- David Adams Richards, Mercy Among the Children

The piety of Job

While the Book of Job on a whole gives no simple answer to thorny theological questions, sections of the book have become extremely important to traditional religious teaching. Preachers often use Job as an exemplary man of faith, who refuses to curse God even after he has lost his wealth, his possessions, and his ten children. This of course, takes Job's attitude in the first two chapters as representative of his general posture.

One of Job's more hopeful declarations during the middle chapters of the book is also used, particularly by Christian preachers, to demonstrate Job's faith in the resurrection of the dead at the second coming of Christ.

- I know that my Redeemer lives,

- and that in the end he will stand upon the earth.

- And after my skin has been destroyed,

- yet in my flesh I will see God. (19:25-26)

Critical views

A great diversity of opinion exists as to the authorship of this book. It is clearly in the category of Wisdom Literature, along with Psalms and Proverbs. However, it rejects the simplistic formula of most of hte Proverbs, grappling with the problem of evil and suffering in a manner more akin to the Book of Eccelesiastes. Most modern scholars place it in around the time of the Babylonian exile.

The Talmud (Tractate Bava Basra 15a-b) maintains that the Book of Job was written by Moses. There is a minority view among the rabbis that says Job never existed (Midrash Genesis Rabbah LXVII, Talmud Bavli, Bava Batra 15a). In this view, Job was a literary creation by a prophet to convey a divine message or parable. On the other hand, the Talmud (in Tractate Baba Batra 15a-16b) goes to great lengths trying to ascertain when Job actually lived, citing many opinions and interpretations by the leading sages.

The Sumerian text The Ludlul Bêl Nimeqi,[1] (c. 1700 B.C.E.) is thought be some to have influenced the Book of Job. It is the lament of a powerful man deeply troubled by the world's evil and yet unable to obtain and answer from his deities. A typical verse resonates with Job's sentiments entirely:

- What in one's heart is contemptible, to one's God is good!

- Who can understand the thoughts of the gods in heaven?

- The counsel of God is full of destruction; who can understand?

- Where may human beings learn the ways of God?

- He who lives at evening is dead in the morning (v. 35)

Whatever the story's origins, the land of Edom, has been retained as the background. Rabbinical source affirm Job to have been one of several Gentile prophets who taught Yahweh's ways to non-Iraelites.

In the final form of Job, various interpolations are thought to have been made in the text of the central poem, which consists only of the dialogue between Job and his three friends. The speeches of Elihu (Chapters 32-37), are though by many to be a later addition. So too are the prolog and epilogue, which wrap the dialogue into a very different context the possible original.

Subjects of more contention among scholars are the identity of claimed corrections and revisions of Job's speeches, which are claimed to have been made for the purpose of harmonizing them with the orthodox doctrine of retribution. A prime example of such a claim is the translation of the last line Job speaks (42:6), which is extremely problematic in the Hebrew. Traditional translations have him say, "Therefore I despise myself, and repent in dust and ashes." Some argue that in the original version it was not himself that Job despised, but the situation in which God had put him, and perhaps even God himself.

The Testament of Job, a book found in the Pseudepigrapha, has a parallel account to the narrative to the book of Job. There are legendary details such as the fate of Job's wife, the inheritance of Job's daughters, and the ancestry of Job. In addition Satan's hatred of Job is explained on the basis of Job's having previously destroyed an idolatrous temple, and Job is portrayed in a much more heroic and pious light.

External links

- Jewish translations:

- Iyov - Job (Judaica Press) translation with Rashi's commentary at Chabad.org

- Christian translations:

- Job at The Great Books (New Revised Standard Version)

- Job at Wikisource (Authorised King James Version)

- Other translations:

- The Trial of Job (translation as drama with hyperlinked notes)

- The Book Of Job The Musical (translation as musical)

- Jewish Cantillations

- Sephardic Cantillations for the Book of Job by David M. Betesh and the Sephardic Pizmonim Project

Related articles:

- Excerpts from "Answer to Job" by Carl Jung

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Job; Book of Job

- Easton's Bible Dictionary, 1897: Job; Book of Job

- "Short Articles on the Book of Job": Bill Long

- "Putting God on Trial- The Biblical Book of Job" by Robert Sutherland A complete online commentary.

- Job at the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Biblical Job: A Vision of God

- Exegetical Paper on Job 19:23-27 by Rudolph E. Honsey

- A Proposed Connection between Job and Tobias, Tobit's son

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Ludlul Bêl Nimeqi www.fordham.edu. Retrieved July 10, 2007.