Difference between revisions of "Bastille Day" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 131: | Line 131: | ||

In recent years the parade has started with military bands from the French Armed Forces taking the stage with band exhibitions and drill shows, sometimes including displays from foreign service troops and mounted units; plus military and civil choirs singing classic French patriotic songs. This opening ends with the playing of [[La Marseillaise]], the National Anthem of France. | In recent years the parade has started with military bands from the French Armed Forces taking the stage with band exhibitions and drill shows, sometimes including displays from foreign service troops and mounted units; plus military and civil choirs singing classic French patriotic songs. This opening ends with the playing of [[La Marseillaise]], the National Anthem of France. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Special Anniversary Celebrations== | ==Special Anniversary Celebrations== | ||

Revision as of 17:14, 18 July 2019

| Bastille Day | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fireworks at the Eiffel Tower, Paris, 2017 | |

| Also called | French National Day (Fête nationale) The Fourteenth of July (Quatorze juillet) |

| Observed by | France |

| Type | National day |

| Significance | Commemorates the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789,[1] and the unity of the French people at the Fête de la Fédération on 14 July 1790 |

| Date | 14th July |

| Celebrations | Military parades, fireworks, concerts, balls |

Bastille Day is the common name given in English-speaking countries to the national day of France, which is celebrated on July 14 each year. In French, it is formally called la Fête nationale ("The National Celebration") and commonly and legally le 14 juillet ("the 14th of July").

The French National Day is the anniversary of Storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789, a turning point of the French Revolution, as well as the Fête de la Fédération which celebrated the unity of the French people on 14 July 1790. Celebrations are held throughout France. The oldest and largest regular military parade in Europe is held on the morning of 14 July, on the Champs-Élysées in Paris in front of the President of the Republic, along with other French officials and foreign guests.

History

Storming of the Bastille

The Storming of the Bastille (French: Prise de la Bastille) occurred in Paris, France, on the afternoon of 14 July 1789. The prison contained only seven inmates at the time of its storming but was seen by the revolutionaries as a symbol of the monarchy's abuse of power; its fall was the flashpoint of the French Revolution.

During the reign of Louis XVI, France faced a major economic crisis. This crisis was caused in part by the cost of intervening in the American Revolution and exacerbated by a regressive system of taxation.[2] On 5 May 1789, the Estates General of 1789 convened to deal with this issue, but were held back by archaic protocols and the conservatism of the second estate: representing the nobility[3] who made up less than 2% of France's population.[2]

On 17 June 1789, the third estate, with its representatives drawn from the commoners, reconstituted themselves as the National Assembly, a body whose purpose was the creation of a French constitution. The king initially opposed this development, but was forced to acknowledge the authority of the assembly, which renamed itself the National Constituent Assembly on 9 July.

On 11 July 1789, Louis XVI—acting under the influence of the conservative nobles of his privy council—dismissed and banished his finance minister, Jacques Necker (who had been sympathetic to the Third Estate) and completely reconstructed the finance ministry.

Many Parisians presumed Louis's actions to be the start of a royal coup by the conservatives and began open rebellion when they heard the news the next day. They were also afraid that arriving Royal soldiers had been summoned to shut down the National Constituent Assembly, which was meeting at Versailles, and the Assembly went into nonstop session to prevent eviction from their meeting place once again. Paris was soon consumed with riots, anarchy, and widespread looting. The mobs soon had the support of the French Guard, including arms and trained soldiers, because the royal leadership essentially abandoned the city.

On July 14, the people of Paris, fearful that they and their representatives would be attacked by the royal army or by foreign regiments of mercenaries in the king's service, and seeking to gain ammunition and gunpowder for the general populace. then stormed the Bastille. The Bastille was a fortress-prison in Paris which had often held people jailed on the basis of lettres de cachet (literally "signet letters"), arbitrary royal indictments that could not be appealed and did not indicate the reason for the imprisonment. Known for holding political prisoners whose writings had displeased the royal government, it was thus a symbol of the absolutism of the monarchy. As it happened, at the time of the attack in July 1789 there were only seven inmates, none of great political significance.[4] The fortress also held a large cache of ammunition and gunpowder.

Reinforced by mutinous Gardes Françaises ("French Guards"), whose usual role was to protect public buildings, the mob proved a fair match for the fort's defenders, and Governor de Launay, the commander of the Bastille, capitulated and opened the gates to avoid a mutual massacre. However, possibly because of a misunderstanding, fighting resumed. According to the official documents, about 200 attackers and just one defender died in the initial fighting, but in the aftermath, de Launay and seven other defenders were killed, as was Jacques de Flesselles, the prévôt des marchands ("provost of the merchants"), the elected head of the city's guilds, who under the feudal monarchy also had the competences of a present-day mayor.[5]

Shortly after the storming of the Bastille, late in the evening of 4 August, after a very stormy session of the Assemblée constituante, feudalism was abolished. On 26 August, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen) was proclaimed (Homme with an uppercase h meaning "human", while homme with a lowercase h means "man").[6]

Fête de la Fédération

As early as 1789, the year of the storming of the Bastille, preliminary designs for a national festival were underway. These designs were intended to strengthen the country's national identity through the celebration of the events of 14 July 1789.[7] One of the first designs was proposed by Clément Gonchon, a French textile worker, who presented his design for a festival celebrating the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille to the French city administration and the public on 9 December 1789.[8] There were other proposals and unofficial celebrations of 14 July 1789, but the official festival sponsored by the National Assembly was called the Fête de la Fédération.[9]

The Fête de la Fédération on 14 July 1790 was a celebration of the unity of the French nation during the French Revolution. The aim of this celebration, one year after the Storming of the Bastille, was to symbolise peace. The event took place on the Champ de Mars, which was located far outside of Paris at the time. The work needed to transform the Champ de Mars into a suitable location for the celebration was not on schedule to be completed in time. On the day recalled as the Journée des brouettes ("The Day of the Wheelbarrow"), thousands of Parisian citizens gathered together to finish the construction needed for the celebration.[10]

The day of the festival, the National Guard assembled and proceeded along the boulevard du Temple in the pouring rain, and were met by an estimated 260,000 Parisian citizens at the Champ de Mars.[11] A mass was celebrated by Talleyrand, bishop of Autun. The popular General Lafayette, as captain of the National Guard of Paris and a confidant of the king, took his oath to the constitution, followed by King Louis XVI. After the end of the official celebration, the day ended in a huge four-day popular feast and people celebrated with fireworks, as well as fine wine and running nude through the streets in order to display their great freedom.

The Fête de la Fédération (Festival of the Federation) was a massive holiday festival held throughout France in honour of the French Revolution. It is the precursor of the Bastille Day which is celebrated every year in France on 14 July, celebrating the Revolution itself, as well as National Unity.

First celebrated in 1790, it commemorated the revolution and events of 1789 which had culminated in a new form of national government, a constitutional monarchy led by a representative Assembly.

The inaugural fête of 1790 was set for July 14th, so it would also coincide with the first anniversary of the storming of the Bastille although that is not what was itself celebrated. At this relatively calm stage of the Revolution, many people considered the country's period of political struggle to be over. This thinking was encouraged by counter-revolutionary monarchiens, and the first fête was designed with a role for King Louis XVI that would respect and maintain his royal status. The occasion passed peacefully and provided a powerful, but illusory, image of celebrating national unity after the divisive events of 1789–1790.

Background

After the initial revolutionary events of 1789, France's ancien régime had shifted into a new paradigm of constitutional monarchy. By the end of that year, towns and villages throughout the country had begun to join together as fédérations, fraternal associations which commemorated and promoted the new political structure.[12] A common theme among them was a wish for a nationwide expression of unity, a fête to honour the Revolution. Plans were set for simultaneous celebrations in July 1790 all over the nation, but the fête in Paris would be the most prominent by far. It would feature the King, the royal family, and all the deputies of the National Constituent Assembly, with thousands of other citizens predicted to arrive from all corners of France.

Preparation

The event took place on the Champ de Mars, which was at the time far outside Paris. The vast stadium had been financed by the National Assembly, and completed in time only with the help of thousands of volunteer laborers from the Paris region. During these "Wheelbarrow Days"(journée des brouettes), the festival workers popularised a new song that would become an enduring anthem of France, Ah! ça ira.[13]

Enormous earthen stands for spectators were built on each side of the field, with a seating capacity estimated at 100,000.[14] The Seine was crossed by a bridge of boats leading to an altar where oaths were to be sworn. The new military school was used to harbour members of the National Assembly and their families. At one end of the field, a huge tent was the king's step, and at the other end, a triumphal arch was built. At the centre of the field was an altar for the mass.

Official celebration

The feast began as early as four in the morning, under a strong rain which would last the whole day (the Journal de Paris had predicted "frequent downpours").

Fourteen thousand fédérés came from the province, every single National Guard unit having sent two men out of every hundred. They were ranged under eighty-three banners, according to their département. They were brought to the place where the Bastille once stood, and went through Saint-Antoine, Saint-Denis and Saint-Honoré streets before crossing the temporary bridge and arriving at the Champ de Mars.

A mass was celebrated by Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, bishop of Autun under the ancien régime. At this time, the first French Constitution was not yet completed, and it would not be officially ratified until September 1791. But the gist of it was understood by everyone, and no one was willing to wait. Lafayette led the President of the National Assembly and all the deputies in a solemn oath to the coming Constitution:

| “ | We swear to be forever faithful to the Nation, to the Law and to the King, to uphold with all our might the Constitution as decided by the National Assembly and accepted by the King, and to remain united with all French people by the indissoluble bonds of brotherhood.[15] | ” |

Afterwards, Louis XVI took a similar vow: "I, King of the French, swear to use the power given to me by the constitutional act of the State, to maintain the Constitution as decreed by the National Assembly and accepted by myself."[16] The title "King of the French", used here for the first time instead of "King of France (and Navarre)", was an innovation intended to inaugurate a popular monarchy which linked the monarch's title to the people rather than the territory of France.[17] The Queen Marie Antoinette then rose and showed the Dauphin, future Louis XVII, saying: "This is my son, who, like me, joins in the same sentiments."[18]

The festival organisers welcomed delegations from countries around the world, including the recently established United States. John Paul Jones, Thomas Paine and other Americans unfurled their Stars and Stripes at the Champ de Mars, the first instance of the flag being flown outside of the United States.[19]

Popular feast

After the end of the official celebration, the day ended in a huge popular feast. It was also a symbol of the reunification of the Three Estates, after the heated Estates-General of 1789, with the Bishop (First Estate) and the King (Second Estate) blessing the people (Third Estate). In the gardens of the Château de La Muette, a meal was offered to more than 20,000 participants, followed by much singing, dancing, and drinking. The feast ended on the 18 July.

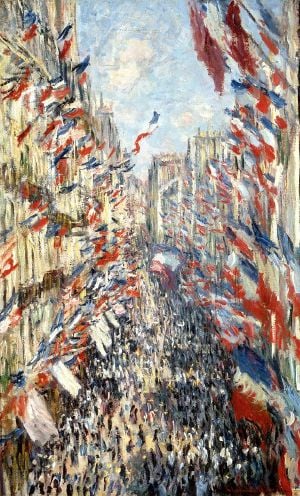

Origin of the current celebration

On 30 June 1878, a feast was officially arranged in Paris to honour the French Republic (the event was commemorated in a painting by Claude Monet).[20] On 14 July 1879, there was another feast, with a semi-official aspect. The day's events included a reception in the Chamber of Deputies, organised and presided over by Léon Gambetta,[21] a military review at Longchamp, and a Republican Feast in the Pré Catelan.[22] All through France, Le Figaro wrote, "people feasted much to honour the storming of the Bastille".[23]

In 1880, the government of the Third Republic wanted to revive the 14 July festival. The campaign for the reinstatement of the festival had been underway for nearly a decade, sponsored by the notable politician Léon Gambetta and scholar Henri Baudrillant.[24] On 21 May 1880, Benjamin Raspail proposed a law, signed by sixty-four members of government, to have "the Republic adopt 14 July as the day of an annual national festival". There were many disputes over which date to be remembered as the national holiday, including 4 August (the commemoration of the end of the feudal system), 5 May (when the Estates-General first assembled), 27 July (the fall of Robespierre), and 21 January (the date of Louis XVI's execution).[25] The government decided that the date of the holiday would be 14 July, but it was still somewhat problematic. The events of 14 July 1789 were illegal under the previous government, which contradicted the Third Republic's need to establish legal legitimacy.[26] French politicians also did not want the sole foundation of their national holiday to be rooted in a day of bloodshed and class-hatred as the day of storming the Bastille was. Instead, they based the establishment of the holiday as a dual celebration of the Fête de la Fédération, a festival celebrating the one year anniversary of 14 July 1789, and the storming of the Bastille.[27] The Assembly voted in favor of the proposal on 21 May and 8 June, and the law was approved on 27 and 29 June. The law was made official on 6 July 1880.

In the debate leading up to the adoption of the holiday, Senator Henri Martin, who wrote the National Day law,[27] addressed the chamber on 29 June 1880:

Do not forget that behind this 14 July, where victory of the new era over the Ancien Régime was bought by fighting, do not forget that after the day of 14 July 1789, there was the day of 14 July 1790 (...) This [latter] day cannot be blamed for having shed a drop of blood, for having divided the country. It was the consecration of the unity of France (...) If some of you might have scruples against the first 14 July, they certainly hold none against the second. Whatever difference which might part us, something hovers over them, it is the great images of national unity, which we all desire, for which we would all stand, willing to die if necessary.[28]

Today, the celebration is formally called la Fête nationale ("The National Celebration") and commonly and legally le 14 juillet ("the 14th of July").[29]

Bastille Day Celebrations today

Bastille Day today celebrates French culture. A national public holiday, schools, government offices, and many businesses are closed allowing people participate in public celebrations held in Paris and other cities. These events may include a parade, dancing, as well as communal meals, parties and a spectacular fireworks display.

Of particular note is the military parade in Paris, opened by the French president, including service men and women of various units, the Paris Fire Brigade, and a fly-past by planes and helicopters of the French Air Force and Naval Air Force. Smaller military parades are held in French garrison cites (most notably Marseille, Toulon, Brest, and Belfort).

The Bastille Day military parade is the French military parade that has been held on the morning of 14 July each year in Paris since 1880. While previously held elsewhere within or near the capital city, since 1918 it has been held on the Champs-Élysées, with the participation of the Allies as represented in the Versailles Peace Conference, and with the exception of the period of German occupation from 1940 to 1944 (when the ceremony took place in London under the command of General Charles de Gaulle). The parade passes down the Champs-Élysées from the Arc de Triomphe to the Place de la Concorde, where the President of the French Republic, his government and foreign ambassadors to France stand. In some years, invited detachments of foreign troops take part in the parade and foreign statesmen attend as guests.

Bastille Day military parade

Originally a popular feast, Bastille day became militarized during the Directory or Directorate (le Directoire), a five-member committee that governed France from 2 November 1795, when it replaced the Committee of Public Safety, until 9 November 1799, when it was overthrown by Napoleon Bonaparte. Under Napoleon, the celebration lost much of its importance, though it came back into fashion during the Third Republic.

The Fourteenth of July became the official national celebration on 28 June 1880, and a decree of 6 July the same year linked a military parade to it. Between 1880 and 1914 the celebrations were held at the Longchamp Racecourse in the Bois de Boulogne, Paris.

Since World War I the parade has been held on the Champs-Élysées, the first occasion being the défilé de la Victoire ("Victory parade") led by Marshals Joseph Joffre, Ferdinand Foch and Philippe Pétain on 14 July 1919. This was not however a French National Holiday parade, although held upon the same date, but one agreed upon by the Allied delegations to the Versailles Peace Conference. A separate Victory parade of Allied troops was held in London four days later.[30]

On the occasion of 14 July 1919 parade in Paris, detachments from all of France's World War I allies took part in the parade, together with colonial and North African units from France's overseas Empire.[31]

In the Second World War, the German troops occupying Paris and Northern France paraded along the same route. A victory parade under General de Gaulle was held upon the restoration in 1945 of Paris to French rule. Within the period of occupation by the Germans a company of the commando Kieffer of the Forces Navales Françaises Libres had continued the French National Holiday parade in the streets of London.

In 1971 female personnel were included for the first time among the troops parading.

Under Valéry Giscard d'Estaing the parade route was changed each year with troops marching down from the Place de la Bastille to the Place de la République to commemorate popular outbreaks of the French Revolution:[32]

Under Presidents François Mitterrand and Jacques Chirac the parade route returned to the Champs-Elysées where it continues to be held. In 1994, troops of the Eurocorps, including German soldiers, paraded on the invitation of François Mitterrand. The event was seen as symbolic of both European integration, and German-French reconciliation.[33]

In recent years the parade has started with military bands from the French Armed Forces taking the stage with band exhibitions and drill shows, sometimes including displays from foreign service troops and mounted units; plus military and civil choirs singing classic French patriotic songs. This opening ends with the playing of La Marseillaise, the National Anthem of France.

Special Anniversary Celebrations

- 1989: France celebrated the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution, notably with a monumental show on the Champs-Élysées in Paris, directed by French designer Jean-Paul Goude. President François Mitterrand acted as host for invited world leaders.[34]

- 2004: To commemorate the centenary of the Entente Cordiale, the British led the military parade with the Red Arrows flying overhead.[35]

- 2007: To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome, the military parade was led by troops from the 26 other EU member states, all marching at the French time.[36]

- 2014: To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the beginning to the First World War, representatives of 80 countries who fought during this conflict were invited to the ceremony. The military parade was opened by 76 flags representing each of these countries.[37]

- 2017: To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the United States of America's entry into the First World War and the long-standing partnership between the countries, U.S. service members marched in the Bastille Day parade in Paris, as smoke trails billow overhead from a flyover conducted by French Alpha jets.

Bastille Day celebrations in other countries

Many other countries also celebrate Bastille Day, especially those with large French communities or specific ties to France.

For example, Liège in Wallonia, the French speaking region of Belgium has celebrated Bastille Day each year since the end of the First World War, as Liège was decorated by the Légion d'Honneur for its unexpected resistance during the Battle of Liège.[38] Specifically in Liège, celebrations of Bastille Day have been known to be bigger than the celebrations of the Belgian National holiday. The city also hosts a fireworks show outside of Congress Hall and many unofficial events celebrate the relationship between France and the city of Liège.[39]

When France annexed a large portion of what is now French Polynesia in 1881, following a lengthy struggle with British colonialists and Protestant missionaries, Tahitians were permitted to participate in sport, singing, and dancing competitions one day a year: Bastille Day.[40] The single day of celebration evolved into the major Heiva i Tahiti festival in Papeete Tahiti, where traditional events such as canoe races, tattooing, singing and dancing competitions, and fire walks are held.[41]

Countries such as Canada, especially in Quebec, who have significant French populations sponsor major celebrations on Bastille Day. The Unites States has numerous cities, including New Orleans with its French Creole roots, that conduct annual celebrations of Bastille Day. The different cities celebrate with many French staples such as food, music, games, and sometimes the recreation of famous French landmarks.

Notes

- ↑ La fête nationale du 14 juillet "The national holiday of July 14")|Official Website of Elysée. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Simon Schama, Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution, ISBN 0-670-81012-6

- ↑ Munro Price, p. 20 The Fall of the French Monarchy, ISBN 0-330-48827-9

- ↑ G A Chevallaz, Histoire générale de 1789 à nos jours, p. 22, Payot, Lausanne 1974

- ↑ J Isaac, L'époque révolutionnaire 1789–1851, p. 60, Hachette, Paris 1950

- ↑ J Isaac, L'époque révolutionnaire 1789–1851, p. 64, Hachette, Paris 1950.

- ↑ Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen (1997). The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and Freedom. Duke Press University, 151. ISBN 9780822382751.

- ↑ Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen (1997). The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and Freedom. Duke University Press, 152. ISBN 9780822382751.

- ↑ Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen (1997). The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and Freedom. Duke University Press, 153. ISBN 9780822382751.

- ↑ Prendergast, Christopher (2008). The Fourteenth of July. Profile Books Ltd., 105–106. ISBN 9781861979391.

- ↑ Prendergast, Christopher (2008). The Fourteenth of July. Profile Books Ltd, 106–107. ISBN 9781861979391.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 112.

- ↑ Hanson, p. 53.

- ↑ La fête nationale du 14 juillet (in French). Elysee.fr. Office of the President of the French Republic (2015). Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ↑ Mignet, p. 158: "Nous jurons d'être à jamais fidèles à la nation, à la loi et au roi, de maintenir de tout notre pouvoir la Constitution décrétée par l'Assemblée nationale et acceptée par le roi et de demeurer unis à tous les Français par les liens indissolubles de la fraternité."

- ↑ Mignet, p. 158: "Moi, roi des Français, je jure d'employer tout le pouvoir qui m'est délégué par l'acte constitutionnel de l'état, à maintenir la constitution décrétée par l'Assemblée nationale et acceptée par moi."

- ↑ Indicative of a constitutional monarchy rather than an absolute one, the style "King of the French" was in effect 1791–1792 and was revived after the July Revolution in 1830.

- ↑ Bonifacio and Maréchal, p. 96: "Voilà mon fils, il s'unit, ainsi que moi, aux mêmes sentiments."

- ↑ Unger, p. 266.

- ↑ Adamson, Natalie (15 August 2009). Painting, politics and the struggle for the École de Paris, 1944–1964. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-5928-0. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ↑ Nord, Philip G. (2000). Impressionists and politics: art and democracy in the nineteenth century. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-20695-2. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ↑ Nord, Philip G. (1995). The republican moment: struggles for democracy in nineteenth-century France. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-76271-8. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ↑ "Paris Au Jour Le Jour", 16 July 1879, p. 4. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ↑ Prendergast, Christopher (2008). The Fourteenth of July. Profile Books Ltd, 127. ISBN 9781861979391.

- ↑ Prendergast, Christopher (2008). The Fourteenth of July. Profile Books Ltd, 129. ISBN 9781861979391.

- ↑ Prendergast, Christopher (2008). The Fourteenth of July. Profile Books Ltd, 130. ISBN 9781861979391.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Schofield, Hugh (14 July 2013). Bastille Day: How peace and revolution got mixed up.

- ↑ Le Quatorze Juillet at the Greeting Card Universe Blog

- ↑ Article L. 3133-3 of French labour code www.legifrance.gouv.fr. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ↑ London 'Peace Parade' 19 July 1919 {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}. Retrieved 12 August 2010

- ↑ pages 50–51 "To Lose a Battle – France 1940, Template:ISBN

- ↑ http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}

- ↑ http://www.elysee.fr {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}

- ↑ Longworth, R.C., "French Shoot The Works With Soaring Bicentennial French", Chicago Tribune, 15 July 1989. (written in en)

- ↑ Broughton, Philip Delves, "Best of British lead the way in parade for Bastille Day", The Telegraph, 14 July 2004. (written in en-GB)

- ↑ The 14th of July : Bastille Day (in en-EN).

- ↑ "Bastille Day in pictures: Soldiers from 76 countries march down Champs-Elysees", The Telegraph, 14 July 2014. (written in en-GB)

- ↑ Travel Picks: Top 10 Bastille Day celebrations Reuters, July 13, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ↑ An unusual Bastille Day: in Liège, Belgium Eurofluence, July 19, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ↑ The Best Festival You've Never Heard Of: The Heiva in Tahiti X Days in Y. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ↑ David Trumper, 7 places outside France where Bastille Day is celebrated WorldFirst.com, July 11, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adamson, Natalie. Painting, Politics and the Struggle for the École de Paris, 1944–1964. Routledge, 2009. ISBN 0754659283

- Bonifacio, Antoine, and Paul Maréchal. La France, l'Europe et le monde, de 1715 à 1870. Paris: Hachette, 1965. OCLC 679992827

- Hanson, Paul R. Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Scarecrow Press, 2004. ISBN 0810850524

- Hibbert, Christopher. The Days of the French Revolution. William Morrow and Co., 1999. ISBN 0688169783

- Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen, and Rolf Reichardt. The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and Freedom. Duke University Press Books, 1997. ISBN 0822319020

- Mignet, François-Auguste-Alexis. Historie de la revolution francaise depuis 1789 jusqu'en 1814 Wentworth Press, 2018. ISBN 0341075140

- Nord, Philip. The Republican Moment: Struggles for Democracy in Nineteenth-Century France. Harvard University Press, 1995. ISBN 0674762711

- Nord, Philip. Impressionists and Politics: Art and Democracy in the Nineteenth Century. Routledge, 2000. ISBN 0415206952

- Prendergast, Christopher. The Fourteenth of July and the Taking of the Bastille. Profile Books, 2009. ISBN 1861979398

- Unger, Harlow Giles. Lafayette. Wiley, 2007. ISBN 047144586X

External links

All links retrieved

- What Actually Happened on the Original Bastille Day by Emma Ockerman, TIME, July 13, 2016.

- Bastille Day History.com.

- Bastille Day in France

- Te Deum for the Federation of 14 July 1790, hymn by composer François-Joseph Gossec

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.