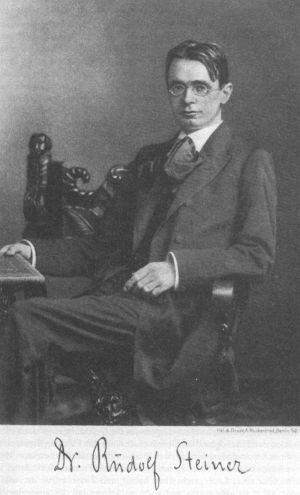

Rudolf Steiner (February 27, 1861 - March 30, 1925) was an Austrian philosopher, literary scholar, architect, playwright, educator, and social thinker. The founder of "anthroposophy," he is well known for its numerous practical applications, including Waldorf education, biodynamic agriculture, the Camphill movement for handicapped adults and children, anthroposophical medicine, the new art of eurythmy and other new impulses in art, architecture, and others. His prolific writings reveal deep philosophical, social, and spiritual insights regarding the nature of human society. Many of these ideas continue to inform and inspire our understanding and improvement of human life, and support the advance toward a better world for all.

Biography

Childhood and education

Rudolf Steiner was born on February 27, 1861 in Donji Kraljevec, Austria. His father was a huntsman in Geras, and later became a telegraph operator and stationmaster on the Southern Austrian Railway. When Rudolf was born, his father was stationed in the Muraköz region (present-northernmost Croatia). When Rudolf was two years old, the family moved into Burgenland, Austria, in the foothills of the eastern Alps.

In his childhood, Steiner was interested in mathematics and philosophy. From 1879 to 1883 he attended the Technische Hochschule (Technical University) in Vienna, where he studied mathematics, physics, and chemistry. In 1882, one of Steiner's teachers at the university in Vienna, Karl Julius Schroer, suggested Steiner's name to Professor Joseph Kurschner, editor of a new edition of Goethe's works. Steiner was then asked to become the edition's scientific editor.[1]

In his autobiography, Steiner related that at 21, on the train between his home village and Vienna, he met a simple herb gatherer, Felix Kogutski, who spoke about the spiritual world "as someone who had his own experiences of it…." This herb gatherer introduced Steiner to a person that Steiner only identified as a "master," and who had a great influence on Steiner's subsequent development, in particular directing him to study the philosophy of Johann Gottlieb Fichte.[2]

In 1891 Steiner earned a doctorate in philosophy at the University of Rostock in Germany with his thesis, later published in expanded form as Truth and Science.

Writer and philosopher

In 1888, as a result of his work for the Kurschner edition, Steiner was invited to the Goethe archives in Weimar to become an editor for the official complete edition of Goethe's works. Steiner remained with the archives until 1896. As well as introductions and commentaries to Goethe's scientific writings, Steiner wrote two books about Goethe's philosophy: The Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World-Conception (1886) and Goethe's Conception of the World (1897). During this time he also collaborated in complete editions of Arthur Schopenhauer's work and that of the writer Jean Paul and wrote articles for various journals.

During this time Steiner wrote what he considered his most important philosophical work, Die Philosophie der Freiheit (The Philosophy of Freedom) (1894), an exploration of epistemology and ethics that suggested a path upon which humans can become spiritually free beings. In 1897, Steiner left the Weimar archives and moved to Berlin. He became the owner, chief editor, and active contributor to the literary journal Magazin f√ľr Literatur, where he hoped to find a readership sympathetic to his philosophy.

In 1899, Steiner married Frau Eunicke and they remained together until her death, in 1911.

Spiritual research

From his decision to "go public" in 1899 with the article on "The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily," until his death in 1925, Steiner articulated an ongoing stream of "experiences of the spiritual world" ‚ÄĒ experiences he said had touched him from an early age on.[3] Steiner aimed to apply his training in mathematics, science, and philosophy to produce rigorous, verifiable presentations of those experiences.[4]

Steiner believed that non-physical beings existed everywhere and that through freely chosen ethical disciplines and meditative training, anyone could develop the ability to experience these beings, as well as the higher nature of oneself and others. Steiner believed that such discipline and training would help a person to become a more creative and loving individual.[5]

Steiner's goal was the development of the philosophical work of Franz Brentano (with whom he had studied) and Wilhelm Dilthey, founders of the phenomenological movement in European philosophy.[6] Steiner was also influenced by Goethe's phenomenological approach to science.[7][8]

Attacks, illness and death

Reacting to the catastrophic situation in post-war Germany, Steiner went on extensive lecture tours promoting his social ideas of the "Threefold Social Order," entailing a fundamentally different political structure. He suggested that only through independence of the cultural, political, and economic realms could such catastrophes as the World War have been avoided. He also promoted a radical solution in the disputed area of Upper Silesia (claimed by both Poland and Germany.) His suggestion that this area be granted at least provisional independence led to his being publicly accused of being a traitor to Germany, an accusation published in the Frankfurter Zeitung, March 4 1921.

In 1919, the political theorist of the National Socialist Movement in Germany, Dietrich Eckart, attacked Steiner and suggested that he was a Jew.[9] In 1921, Adolf Hitler attacked Steiner in an article in the right-wing "Völkischen Beobachter" newspaper[10] and other nationalist extremists in Germany were calling up a "war against Steiner." The 1923 Beer Hall Putsch in Munich led Steiner to give up his residence in Berlin, saying that if those responsible for the attempted coup (Hitler and others) came to power in Germany, it would no longer be possible for him to enter the country. He also warned against the disastrous effects it would have for Central Europe if the National Socialists came to power.[11]

From 1923 on, Steiner showed signs of increasing frailty and illness. However, he continued to lecture widely, and even to travel. He was often giving two, three, or even four lectures daily for courses taking place concurrently. Many of these lectures were for practical areas of life: education, curative eurythmy, speech, and drama. By autumn, 1924, however, he was too weak to continue. His last lecture was held in September of that year. He died on March 30, 1925.

Work

The life work of Rudolf Steiner was his development of Anthroposophy, a philosophy based on the premise that the human intellect has the ability to contact the spiritual world. He derived his epistemology from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's world view, where ‚ÄúThinking‚Ķ is no more and no less an organ of perception than the eye or ear. Just as the eye perceives colors and the ear sounds, so thinking perceives ideas.‚ÄĚ[12]

Philosophy

The philosophical questions of epistemology and freedom were approached by Steiner in two stages. The first was his dissertation, published in expanded form in 1892 as Truth and Knowledge. There, Steiner suggested that there is an inconsistency between Kant's philosophy, which postulated that the essential verity of the world was inaccessible to human consciousness, and modern science, which assumes that all influences can be found in what Steiner termed the sinnlichen und geistlichen (sensory and mental/spiritual) world to which we have access. Steiner termed Kant's "Jenseits-Philosophie" (philosophy of an inaccessible beyond) a stumbling block in achieving a satisfying philosophical viewpoint.[13]

Steiner postulated that the world is essentially an indivisible unity, but that our consciousness divides it into the sense-perceptible appearance, on the one hand, and the formal nature accessible to our thinking, on the other. He saw in thinking itself an element that can be strengthened and deepened sufficiently to penetrate all that our senses do not reveal to us. Steiner thus explicitly denied all justification to a division between faith and knowledge; otherwise expressed, between the spiritual and natural worlds. Their apparent duality is conditioned by the structure of our consciousness, which separates perception and thinking, but these two faculties give us two complementary views of the same world. In perception (the path of natural science) and perceiving the process of thinking (the path of spiritual training), it is possible to discover a hidden inner unity between the two poles of our experience.

Steiner viewed human consciousness, indeed, all human culture, as a product of natural evolution that transcends itself; nature becomes self-conscious in the human being. He thus affirmed Darwin's and Haeckel's evolutionary perspectives but extended them beyond their materialistic consequences. He seems here to build upon Vladimir Solovyov, whose description of the nature of human consciousness is virtually identical with Steiner's:

In human beings, the absolute subject-object appears as such, i.e. as pure spiritual activity, containing all of its own objectivity, the whole process of its natural manifestation, but containing it totally ideally - in consciousness....The subject knows here only its own activity as an objective activity (sub specie object). Thus, the original identity of subject and object is restored in philosophical knowledge.[14]

The Anthroposophical Society and its cultural activities

Steiner developed "Anthroposophy," also called "spiritual science," as a spiritual/religious philosophy. It states that anyone who "conscientiously cultivates sense-free thinking" can attain experience of and insights into the spiritual world.[15] Anthroposophical research seeks to attain in its investigations of the spiritual world the precision and clarity of natural science's investigations of the physical world, thus applying the methodology of modern science to the realm of spiritual experience.

The word anthroposophy is derived from the Greek roots anthropo meaning human, and sophia meaning wisdom.

Steiner characterized "Anthroposophy" as follows:

Anthroposophy is a path of knowledge to guide the Spirit of the human being to the Spiritual in the universe. It arises in man as a need of the heart, of the life of feeling: and it can be justified inasmuch as it can satisfy this inner need.[16]

Anthroposophists are those who experience, as an essential need of life, certain questions on the nature of the human being and the universe, just as one experiences hunger and thirst.[17]

Eurythmy

"Eurythmy" is a movement art originated by Rudolf Steiner in the early twentieth century. Primarily a performing art, eurythmy is also used in dance therapy and taught to children for its pedagogical value (especially in Waldorf Schools). The word eurythmy stems from Greek roots meaning beautiful or harmonious rhythm and was used by Greek architects to refer to a harmonious balance of proportion in a design or building.[18] Together with his wife, Rudolf Steiner developed the art of Eurythmy, sometimes referred to as "visible speech and visible song." According to the principles of Eurythmy, there are archetypal movements or gestures that correspond to every aspect of speech - the sounds, or phonemes, the rhythms, the grammatical function, and so on - to every "soul quality" - laughing, despair, intimacy - and to every aspect of music - tones, intervals, rhythms, harmonies.

As a playwright, Steiner wrote four "Mystery Dramas" between 1909 and 1913, including The Portal of Initiation and The Soul's Awakening. They are still performed by Anthroposophical groups.

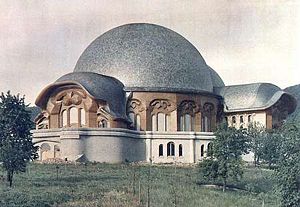

Architecture and sculpture

Steiner developed an organic style of architecture for the design and construction of some 17 buildings. The most significant of these are the first and second Goetheanums, qguxg were intended to house a University for Spiritual Science. In 1913, construction began on the first Goetheanum building, in Dornach, Switzerland. The building, designed by Steiner, was built in part by volunteers who offered craftsmanship or simply a will to learn new skills. Once World War I started in 1914, the Goetheanum volunteers could hear the sound of cannon fire beyond the Swiss border, but despite the war, people from all over Europe worked peaceably side by side on the building's construction. In 1919, the Goetheanum staged the world premiere of a complete production of Goethe's Faust. In this same year, the first Waldorf school was founded in Stuttgart, Germany, and his lecture activity expanded enormously, while the Goetheanum developed as a wide-ranging cultural center. On New Year's Eve, 1922/1923, it was burned down by arson. Steiner immediately began work designing a second Goetheanum building, made of concrete instead of wood which was completed in 1928, three years after his death. He conceived it as an organic extension and metamorphosis of the first building, inspiring and pre-dating architects such as Le Corbusier, and Eero Saarinen's Kennedy Airport. As a sculptor, Steiner's works include The Representative of Humanity (1922). This nine-meter high wood sculpture was a joint project with the sculptor Edith Maryon. This massive sculpture depicting the spiritual forces active in the world and the human being, survived the fire. It is on permanent display at the Goetheanum in Dornach.

Anthroposophical medicine

From the late 1910s, Steiner worked with doctors to create a new approach to medicine. Anthroposophical medicine is a holistic and salutogenetic approach to health. It thus focuses on ensuring that the conditions for health are present in a person; combating illness is often necessary but is insufficient alone. In 1921, pharmacists and physicians gathered under Steiner's guidance to create a pharmaceutical company called Weleda, which now distributes natural medical products worldwide. At around the same time, Ita Wegman founded the first anthroposophic medical clinic in Arlesheim, Switzerland (now called the Wegman Clinic), where she continued Steiner's work after his death.

Biodynamic farming

In 1924, a group of farmers concerned about the future of agriculture requested Steiner's help; Steiner responded with a lecture series on agriculture. This was the origin of biodynamic agriculture, which is now practiced throughout much of Europe, North America, and Australasia.[19] A central concept of these lectures was to "individualize" the farm by producing all needed materials such as manure and animal feed from within what he called the "farm organism." Other aspects of Biodynamic farming include timing activities such as planting in relation to the movement patterns of the moon and planets, and applying "preparations" that consist of natural materials which have been processed in specific ways, to soil, compost piles, and plants with the intention of engaging non-physical beings and elemental forces. Steiner encouraged his listeners to verify his suggestions scientifically, as he had not yet done.

Steiner taught that the introduction of chemical farming was a major problem; the quality of food in his time was degraded, and he believed the source of the problem were artificial fertilizers and pesticides. This, he believed was not only because of the chemical or biological properties involved, but also due to spiritual shortcomings in the whole chemical approach to farming. Steiner considered the world and everything in it as simultaneously spiritual and material in nature, and thus both aspects need to be considered and understood in the development of new techniques and processes in agriculture.

Renewal of religious life

In the 1920s, Steiner was approached by Friedrich Rittlemeyer, an eminent Lutheran pastor with a congregation in Berlin, who asked if it was possible to create a more modern form of Christianity. Soon others joined Rittlemeyer - mostly Protestant pastors, but including at least one Catholic priest. Steiner offered counsel on renewing the sacraments, combining Catholicism's emphasis on a sacred tradition with the Protestant emphasis on freedom of thought and a personal relationship to religious life. Steiner made it clear, however, that the resulting movement for the renewal of Christianity, which became known as the "Christian Community," was a personal gesture of help to a deserving cause. It was not, he emphasized, founded by the movement known as "Spiritual Science" or "Anthroposophy," but by Rittlemeyer and the other founding personalities with Steiner's help and advice. The distinction was important to Steiner because he sought with anthroposophy to create a scientific, not faith-based, spirituality. For those who wished to find more traditional forms, however, a renewal of the traditional religions was also a vital need of the times.

Threefold nature of social life

The year of the German revolution, 1919, Steiner wrote Basic Issues of the Social Question[20] proposing solutions to the social, political, and economic problems of those times. 40,000 copies of this book were printed and widely circulated. At the same time, 500,000 copies of a petition written by Steiner, with suggestions for organizing a threefolding of society, were distributed and published in many daily papers around Struttgart in the south of Germany and an Association for Social Threefolding was founded.[21]

Steiner's various writings and lectures proposed that there were three main spheres of power comprising human society: the cultural, the economic, and the political. In ancient times, those who had political power were also generally those with the greatest cultural/religious power and the greatest economic power. Culture, state, and economy were fused (for example in ancient Egypt). With the emergence of classical Greece and Rome, the three spheres began to become more autonomous. This autonomy went on increasing over the centuries, and with the slow rise of egalitarianism and individualism, the failure to adequately separate economics, politics, and culture was felt increasingly as a source of injustice. Steiner suggested strengthening the following three kinds of social separations:

- Increased separation between the State and cultural life

The state should not be able to control culture: how people think, learn, or worship. A particular religion or ideology should not control the levers of the State. Steiner held that pluralism and freedom were the ideal for education and cultural life.

- Increased separation between the economy and cultual life

The fact that churches, temples, and mosques do not make the ability to enter and participate dependent on the ability to pay, and that libraries and museums are open to all free of charge, is in tune with Steiner‚Äôs notion of a separation between cultural and economic life. In a similar spirit, Steiner held that all families, not just rich ones, should have freedom of choice in education and access to independent, non-government schools for their children. Also, a corporation should not be able to control the cultural sphere by using economic power to bribe schools into accepting ‚Äėeducational‚Äô programs larded with advertising, or by secretly paying scientists to produce research results favorable to the business‚Äôs economic interests.

- Increased separation between the State and the economy (associative economics)

A rich man should be prevented from buying politicians and laws. A politician should not be able to parlay his political position into riches earned by doing favors for businessmen. Slavery is unjust, because it takes something political, a person’s inalienable rights, and absorbs them into the economic process of buying and selling. Steiner advocated a more humanly oriented form of capital economy precisely because unfettered capital tends to absorb the State and human rights into the economic process and transform them into mere commodities.

Steiner held that the French Revolution‚Äôs slogan, ‚ÄúLiberty, Equality, Fraternity,‚ÄĚ expressed in an unconscious way the distinct needs of the three social spheres at the present time: liberty in cultural life, equality in a democratic political life, and (uncoerced) fraternity/sorority in economic life. These values, each one applied to its proper social realm, would tend to keep the cultural, economic, and political realms from merging unjustly, and allow these realms and their respective values to check, balance, and correct one another. The result would be a society-wide separation of powers. Steiner argued that increased autonomy for the three spheres would not eliminate their mutual influence, but would cause that influence to be exerted in a more healthy and legitimate manner, because the increased separation would prevent any one of the three spheres from dominating. In the past, according to Steiner, lack of autonomy had tended to make each sphere merge in a servile or domineering way with the others.

For example, under theocracy, the cultural sphere (in the form of a religious impulse) fuses with and dominates the economic and political spheres. Under communism and state socialism, the political sphere fuses with and dominates the other two spheres. And under the typical sort of capitalist conditions, the economic sphere tends to dominate the other two spheres. Steiner points toward social conditions where domination by any one sphere is increasingly reduced, so that theocracy, communism, and the standard kind of capitalism might all be gradually transcended.

According to Steiner, threefolding is not a social recipe or some utopian program that can be easily and quickly implemented. He taught that it requires a complex open process that began thousands of years ago and will probably continue for thousands more.

Waldorf education

In Steiner’s view of education, separation of the cultural sphere from the political and economic spheres meant education should be available to all children regardless of the ability of families to pay for it. On the elementary and secondary level, education should be provided for by private and/or state scholarships that a family could direct to the school of its choice. Steiner was a supporter of educational freedom, but was flexible, and understood that a few legal restrictions on schools (such as health and safety laws), provided they were kept to an absolute minimum, would be necessary and justified.

Waldorf education was developed by Steiner as an attempt to establish a school system that would facilitate the inclusive, broadly based, balanced development of children. Though he had written a book on education, The Education of the Child in the Light of Anthroposophy 12 years before, his first opportunity to open such a school came in 1919 in response to a request by Emil Molt, the owner and managing director of the Waldorf-Astoria Cigarette Company in Stuttgart, Germany. The name Waldorf thus comes from the factory that hosted the first school. The first year the school was a company school and all teachers were listed as workers at Waldorf Astoria, but beginning with the second year the first school was independent.

Steiner insisted upon four conditions before opening:

- that the school be open to all children;

- that it be coeducational;

- that it be a unified twelve-year school;

- that the teachers, those individuals actually in contact with the children, have primary control over the pedagogy of the school, with a minimum of interference from the state or from economic sources.

Within a few years, many other Waldorf schools modeled on the Stuttgart school opened in other cities. Most of the European schools were closed down by the Nazis but after World War II were reopened.

Waldorf schools aim to "educate the whole child - head, heart, and hands" - to develop the intellect, emotional life, and practical abilities in harmonious balance. This curriculum and pedagogy follows Steiner's pedagogical model of a child's holistic development. Steiner believed that there are distinct seven-year human developmental stages, of which there are three during childhood, each having its own learning requirements. During early childhood, learning (language and skill acquisition) is largely experiential, imitative and sensory-based. In the elementary school years, learning naturally occurs through appealing to the imagination, especially through artistic activity. Finally, during adolescence the capacity for abstract thought and conceptual judgment develops.

Stage 1: birth to age 6 or 7

Waldorf schools emphasize the belief that children in the early stages of life learn through imitation and example.[22][23] In Waldorf schools, oral language development is addressed through circle games (songs, poems, and games in movement), daily story time (normally recited from memory) as well as other activities.[24] Substantial time is given for children to freely play; such an environment is considered to support the physical, emotional, and intellectual growth of the child through assimilative learning.[25] Color, the use of natural materials, and toys and dolls that encourage the imagination are "intrinsic to the uncluttered, warm and homelike, aesthetically pleasing Waldorf environments.[26]

Waldorf early childhood education emphasizes the importance of children experiencing the rhythms of the year and seasons, including seasonal festivals drawn from a variety of traditions. Many Waldorf kindergartens and lower grades ask or require that children be sheltered from media and popular cultural influences, including television and recorded music.

Stage 2: age 7 to puberty

Academic instruction is integrated with arts, spirituality, craft, and physical activity. As Steiner stated in The Education of the Child in the Light of Anthroposophy (1907), "… the child should be laying up in his memory the treasures of thought on which mankind has pondered."

The curriculum is highly challenging, structured, and creative. In Waldorf schools, one teacher often aims to stay with a class as it advances from its first year all the way through to year eight, teaching the main subject lessons. Specialist teachers are utilized for subjects such as foreign languages, handwork and crafts, eurythmy, games and gymnastics, and so forth.

In the middle school years in which the child goes through puberty, some schools employ specialist teachers for mathematics, science, and/or literature as well. These are seen as transitional years when the pupils still need the support of a central teacher, but also the in-depth education possible only through more specialized support teachers. The approach to teaching these years is changing rapidly in Waldorf schools, and the combination of teachers employed in different schools for the academic subjects in the middle school runs the gamut from a central teacher teaching all of these to only using specialist teachers.

Stage 3: after puberty

Following puberty, the child is helped to begin a guided, but independent search for truth in himself and the world around him. As Steiner stated in Education for Adolescents (1922), "The capacity for forming judgments is blossoming at this time and should be directed toward world-interrelationships in every field." Idealism is central to these years, and the education constantly directs pupils to motivating impulses that can stimulate their enthusiasm. It is claimed a combination of highly analytic thinking with idealism is cultivated.

Instead of having one main teacher who teaches most subjects, the students in high school have many specialist teachers. They begin to grasp concepts and analyze the facts and knowledge they learned in the earlier stages. All students continue to take courses in art, music, and crafts on top of the full range of sciences, mathematics, language and literature, and history normal to most academically-oriented schools.

Spiritual festivals and Waldorf schools

Waldorf schools appreciate the spiritual origin of the human being, which many interpret to be religious. Virtually all world religions are included in the curriculum as mythologies or in the study of historical cultures. No particular religion is universally emphasized, but the schools often attempt to bring the local religious beliefs and practices alive inside of the school, as well; in Israel, this occurs through Jewish festivals, in Europe generally through Christian festivals, in Egypt, through Muslim festivals, and so on. The increasingly multi-cultural nature of many societies is transforming the ways these festivals can take place.

Controversies

Rudolf Steiner's views on race and ethnicity

Steiner believed that humanity is made up of individuals first and foremost, each of which exists sui generis (as a unique entity unto him or herself); and that each individual's evolving soul and eternal spirit pass through successive physical incarnations in changing settings and races. For Steiner, of these three elements of every individual, body, soul, and spirit; race and ethnicity are thus transient characteristics, associated with the body used for a particular incarnation, rather than essential aspects of the individual. Moreover, even in a given lifetime's bodily sheath, racial differences are minor influences compared to more individual factors.[27] Through a person's "inner" development, racial or ethnic backgrounds become less significant, and the individual spirit ‚ÄĒ that which is truly unique ‚ÄĒ manifests itself to an even greater degree. Steiner also emphasized that race was rapidly losing any remaining significance for human civilization. One of his central principles was the need to combat prejudice: "any racial prejudice hinders me from looking into a person's soul".[28]

When Steiner described what he believed to be the particular characteristics of races, ethnic groups, nations and other groupings of human beings, some of his characterizations are difficult to reconcile with his more general statements about the subordinate role race and ethnicity play in present-day humanity. These characterizations have been termed racist by critics.[29][30]

Steiner and Antisemitism

Steiner repeatedly criticized the more extreme forms of anti-Semitism of his time, at age 20 describing the anti-Semitic philosophy of Eugen D√ľhring as "barbarian nonsense."[31] In his 30s, he continued to criticize what he described as the ‚Äúoutrageous excesses of the anti-Semites,‚ÄĚ and denounced the ‚Äúraging anti-Semites‚ÄĚ as enemies of human rights. He strongly supported full legal, social, and political equality for Jews ‚ÄĒ advocating their complete assimilation, and questioning the justification for founding a separate Zionist state.[32]

In 1897 he commented:

Value should be attached solely to the mutual exchange between individuals. It is irrelevant whether someone is a Jew or a German … This is so obvious that one feels stupid even putting it into words. So how stupid must one be to assert the opposite!" [33]

Yet, in embracing the notion of assimilation, Steiner pointedly expressed (in 1888, and later) his belief that the Jews needed to let go of their religion, their culture, and even their "way of thinking" ‚ÄĒ in short, their "Jewishness." He wrote:

It certainly cannot be denied that Jewry today still behaves as a closed totality, and as such it has frequently intervened in the development of our current state of affairs in a way that is anything but favorable to European ideas of culture. But Jewry itself has long since outlived its time; it has no more justification within the modern life of peoples, and the fact that it continues to exist is a mistake of world history whose consequences are unavoidable. We do not mean the forms of the Jewish religion alone, but above all the spirit of Jewry, the Jewish way of thinking.[34]

Beginning around the turn of the century, Steiner wrote a series of seven articles for the Mitteilungen aus dem Verein zur Abwehr des Antisemitismus, a magazine devoted to combating anti-Semitism, in which he attacked the anti-Semitism of the era. He continued to support the assimilation of world Jewry into the countries where they lived, arguing in the spirit of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) that living as separate, isolated groups, and continuing to hold on to external rules based on several-thousand-year-old revelations, was outdated and obsolete.[35]

Legacy

Rudolf Steiner's legacy is broad and all-encompassing as was his work. It includes impact on the fields of education, medicine, agriculture, architecture, and art, as well as social movements to improve the lives of disadvantaged people. Some examples follow.

Steiner founded a new approach to artistic speech and drama. Various ensembles work with this approach, called "speech formation" (Sprachgestaltung), and trainings exist in various countries, including England, the United States, Switzerland, and Germany.

During the Anthroposophical Society's Christmas conference in 1923, Steiner founded the School of Spiritual Science, intended as an open university for research and study. This university, which has various sections or faculties, has grown steadily. It is particularly active today in the fields of education, medicine, agriculture, art, natural science, literature, philosophy, sociology, and economics. Steiner spoke of laying the foundation stone of the new society in the hearts of his listeners, while the First Goetheanum's foundation stone had been laid in the earth. He gave a "Foundation Stone meditation" to anchor this.

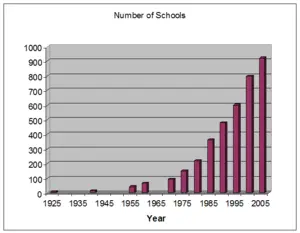

By the early twenty-first century Waldorf schools had expanded to include over 900 schools throughout the world in Europe, North and South America, Africa, Australasia, and Japan. Many public school teachers have brought aspects of Waldorf education into their classrooms, as well. In Europe, especially in Switzerland, there is significant integration of the Waldorf approach and public education. Waldorf education is also practiced in homeschools and special education environments.

Three of Steiner's buildings, including both Goetheanum buildings, have been listed among the most significant works of modern architecture. Steiner himself designed around 13 buildings, many of them significant works in a unique, organic-expressionistic style.[36] Thousands of further buildings have been built by a later generation of anthroposophic architects.[37] One of the most famous contemporary buildings by an anthroposophical architect is the ING Bank in Amsterdam, which has been given many awards for its ecological design and approach to a self-sustaining ecology as an autonomous building.

Early in the twentieth century, when proper care for the handicapped was largely ignored in many countries, anthroposophical homes and communities were founded for the needy. The first was the Sonnenhof in Switzerland, founded by Ita Wegman in 1922. In 1940, the Camphill Movement was founded by Karl König in Scotland. The latter in particular has spread widely, and there are now well over a hundred Camphill communities and other anthroposophical homes for both children and adults in more than twenty-two countries around the world.[38]

Around the world there are a number of innovative banks, companies, charitable institutions, and schools for developing new cooperative forms of business, all working partly out of social ideas. One example is The Rudolf Steiner Foundation (RSF), incorporated in 1984, and as of 2004 with estimated assets of $70 million. RSF provides "charitable innovative financial services." According to the independent organizations Co-op America and the Social Investment Forum Foundation, RSF is "one of the top 10 best organizations exemplifying the building of economic opportunity and hope for individuals through community investing." The first bank founded was the Gemeinschaftsbank f√ľr Leihen und Schenken in Bochum, Germany; it was started in 1974.[39]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Alfred Heidenreich Rudolf Steiner - A Biographical Sketch Retrieved February 17, 1007

- ‚ÜĎ Rudolf Steiner. The Course of My Life. (New York: Steiner Books, 1986, ISBN 0880101598, Chapter III)

- ‚ÜĎ Steiner, Rudolf, Autobiography; Chapters in the Course of My Life: 1861-1907 Steiner Books, January 2006, ISBN 088010600X, Chapter One

- ‚ÜĎ Lindenberg, "Schritte auf dem Weg zur Erweiterung der Erkenntnis," 77

- ‚ÜĎ Rudolf Steiner. How to Know Higher Worlds: The Classic Guide to the Spiritual Journey, (New York: Steiner Books, 2003, ISBN 0880105089. Chapter Six)

- ‚ÜĎ Steiner, Rudolf, Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life: 1861-1907, Steiner Books, January 2006, ISBN 088010600X, Chapter Three.

- ‚ÜĎ J. Bockem√ľhl. Toward a Phenomenology of the Etheric World, (ISBN 0880101156)

- ‚ÜĎ S. Edelglass et al. The Marriage of Sense and Thought. (ISBN 0940262827).

- ‚ÜĎ Uwe Werner. Anthroposophen in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus. (Munich, 1999. ISBN 3486563629), 7

- ‚ÜĎ ibid

- ‚ÜĎ Werner Georg Haverbeck. Rudolf Steiner: Anwalt f√ľr Deutschland: Ursachen und Hintergr√ľnde des Welt-Krieges unseres Jahrhunderts. (Langen M√ľller, 1989, ISBN 3784422802)

- ‚ÜĎ Rudolf Steiner. Goethean Science. (Mercury Press, 1988. ISBN 0936132922)

- ‚ÜĎ Rudolf Steiner ArchiveTruth and Knowledge. retrieved March 6, 2007

- ‚ÜĎ Vladimir Solovyov. The Crisis of Western Philosophy. (Lindisfarne original 1874) 1996. ISBN 0940262738), 42-43)

- ‚ÜĎ Robert McDermott. The Essential Steiner. ISBN 0060653450), 3-11

- ‚ÜĎ Rudolf Steiner. Anthroposophical Leading Thoughts. (London: Rudolf Steiner Press, (original 1924) 1998).

- ‚ÜĎ Rudolf Steiner. Anthroposophical Leading Thoughts. (New York: Steiner Press 1999. ISBN 1855840960)

- ‚ÜĎ Matila Ghyka. The Geometry of Art and Life. (Kessinger Publishing, 2004, ISBN 1417978325)

- ‚ÜĎ Biodynamics: Regional listings.Groups in N. America. www.biodynamics.com.; List of Demeter certifying organizations. www.demeter.net.¬†;Some farms in the world. Retrieved February 1, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Basic Issues of the Social Question] retrieved April 7, 2007 from the Rudolf Steiner Archives. (in German)

- ‚ÜĎ Sune Nordwall,Three-Fold-Movement from The Birth of the Movement for Social Threefolding. www.thebee.se. Retrieved April 7, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Ginsburg and Opper, Piaget's Theory of Intellectual Development. (ISBN 0136751407), 39-40

- ‚ÜĎ Georg Rist and Peter Schneider, Integrating Vocational and General Education: A Rudolf Steiner School. (Hamburg: Unesco Institute for Education, 1979. ISBN 9282010244), 146

- ‚ÜĎ Iona H. Ginsburg, "Jean Piaget and Rudolf Steiner: Stages of Child Development and Implications for Pedagogy," Teachers College Record 84 (2)(1982): 327-337.

- ‚ÜĎ Rist and Schneider, 144

- ‚ÜĎ Carolyn Pope Edwards, "Three Approaches from Europe", Early Childhood Research and Practice (Spring 2002). Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Steiner, Education as a Force for Social Change Hudson 1997, lecture of 23 April 1919.

- ‚ÜĎ Steiner, "Practical Perspectives," Knowledge of Higher Worlds

- ‚ÜĎ The Janus Face of Anthroposophy Institute for Social Ecology. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Ray McDermott, Racism and Waldorf Education Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ Rudolf Steiner: Briefe I (Letters I), 44-5. (GA 38).

- ‚ÜĎ Rudolf Steiner, Gesammelte Aufs√§tze zur Kultur- und Zeitgeschichte 1897-1901 (Collected Essays on Cultural History and Current Events), 198-199.

- ‚ÜĎ Ibid.

- ‚ÜĎ Ibid., 152

- ‚ÜĎ Steiner's articles for this journal appear in his Collected Works GA (GesamtAusgabe) 31: Adolf Bartels, der Literarhistoriker. Mitteilungen aus dem Verein zur Abwehr des Antisemitismus 37 (1901), in: Gesammelte Aufs√§tze (GA 31), 382-386; Die "Post" als Anwalt des Germanentums. Mitteilungen aus dem Verein zur Abwehr des Antisemitismus 30 (1901), Ibid., 387-388; Ein Heine-Hasser. Mitteilungen aus dem Verein zur Abwehr des Antisemitismus 38 (1901), Ibid., 388-393; Der Wissenschaftsbeweis der Antisemiten. Mitteilungen aus dem Verein zur Abwehr des Antisemitismus 40 (1901), Ibid., 393-398; Versch√§mter Antisemitismus. Mitteilungen aus dem Verein zur Abwehr des Antisemitismus 46-48 (1901), Ibid., 398-414; Zweierlei Ma√ü. Mitteilungen aus dem Verein zur Abwehr des Antisemitismus 50 (1901), Ibid., 414-417; Idealismus gegen Antisemitismus. Mitteilungen aus dem Verein zur Abwehr des Antisemitismus 52 (1901), Ibid., 417-419. Steiner's complete early articles are collected in five volumes of the complete edition of his works, GA 29-33.

- ‚ÜĎ Dennis Sharp, "Rudolf Steiner and the Way to a New Style in Architecture," Architectural Association Journal (June 1963)

- ‚ÜĎ Raab and Klingborg, Waldorfschule baut. (Verlag Freies Geistesleben, 2002).

- ‚ÜĎ Camphill in North America Camphill. www.camphill.org.Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Gemeinschaftsbank f√ľr Leihen und Schenken. www.gls.de.Retrieved February 3, 2008.

Major Works

The style and content of Steiner's works vary greatly. Therefore, while it might be stimulating to read a single lecture or book by Steiner, it would probably be a mistake, having read even four or five of his books, to suppose one has a representative picture of the whole body of his work. Out of the 350 volumes of his collected works (including roughly forty written books, and over 6000 published lectures), some of the more significant works include:

- Steiner, Rudolf. [1886] 1978. Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World-Conception. Rudolph Steiner Pr; 2nd edition ISBN 9780910142946

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1891. Truth and Science. (doctoral thesis)

- Steiner, Rudolf. [1894] 2000. The Philosophy of Freedom. Rudolf Steiner Press; Reprint edition. ISBN 9781855840829

- Steiner, Rudolf. [1904] 2003. How to Know Higher Worlds. Steiner Books; 8New Ed edition. ISBN 9780880105088

- Steiner, Rudolf. [1904] 1997. Theosophy. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 9781564598066

- Steiner, Rudolf. [1907] 1996. The Education of the Child. Steiner Books. ISBN 9780880104142

- Steiner, Rudolf. [1913] 1997. An Outline of Esoteric Science. Steiner Books. ISBN 9780880104098

- Steiner, Rudolf. [1913] 2007. Four Mystery Dramas - The Soul's Awakening. Steiner Books. ISBN 9780880105811

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1919. Practical Advice to Teachers. ISBN 0880104678

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1919. Study of Man. (Waldorf Education)

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1919. The Foundations of Human Experience. ISBN 0880103922 - these lectures were given to the teachers just before the opening of the first Waldorf school in Stuttgart.

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1919. Toward Social Renewal.

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1923. Man as Symphony of the Creative Word.

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1924. Anthroposophy and the Inner Life.

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1995. The Genius of Language: Observations for Teachers. Steiner Books. ISBN 0880103868

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1995. The Spirit of the Waldorf School. Steiner Books ISBN 0880103949

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1995. Waldorf Education and Anthroposophy 1. Steiner Books. ISBN 0880103876

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1996. Education for Adolescents. Steiner Books. ISBN 0880104058

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1996. Rudolf Steiner in the Waldorf School¬†: Lectures and Addresses to Children, Parents, and Teachers, 1919‚Äď1924. Steiner Books. ISBN 0880104333

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1996. The Child's Changing Consciousness: As the Basis of Pedagogical Practice. Anthroposophic Press. ISBN 0880104104

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1996. Waldorf Education and Anthroposophy 2. Steiner Books. ISBN 0880103884

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1997. Discussions with Teachers. Steiner Books; New Ed edition. ISBN 0880104082

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1997. Education As a Force for Social Change. Steiner Books. ISBN 0880104112

- Steiner, Rudolf. 1998. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner: 1919‚Äď1924. Steiner Books. ISBN 0880104589

- Steiner, Rudolf. 2002. The renewal of education through the science of the spirit - these lectures were held in Basel in 1920. Steiner Books. ISBN 0880104554

- Steiner, Rudolf. 2004. A Modern Art of Education. Steiner Books; Rev Ed edition. ISBN 0880105119

- Steiner, Rudolf. 2004. The Spiritual Ground of Education. Steiner Books; New Ed edition. ISBN 0880105135

- Steiner, Rudolf. 2007. Soul Economy: Body, Soul, and Spirit in Waldorf Education. Anthroposophic Press; Rev edition. ISBN 0880105178

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bärtges, C. and N. Lyons. Educating as an Art. New York, NY: Steiner Books, 2003. ISBN 0880105313

- Blunt, Richard. Waldorf Education. Theory and Practice. Novalis Press, Cape Town, 1995. ISBN 0958388547

- Bockem√ľhl, J. Toward a Phenomenology of the Etheric World. New York, NY: Steiner Books, 1996. ISBN 0880101156

- Edelglass, Stephen (ed). The Marriage of Sense and Thought: Imaginative Participation in Science. (Renewal in Science) Great Barrington, MA: Lindisfarne Books; Rev Sub edition, 1997. ISBN 0940262827

- Ghyka, Matila. The Geometry of Art and Life. Kessinger Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1417978325

- Ginsburg, Iona H., and Sylvia Opper. Piaget's Theory of Intellectual Development, 3rd ed. Prentice Hall, 1987. ISBN 013675158X

- Harwood, A.C. The Recovery of Man in Childhood. Great Barrington, MA: Myrin Institute, 2001. ISBN 0913098531

- Haverbeck, Werner Georg. Rudolf Steiner: Anwalt f√ľr Deutschland: Ursachen und Hintergr√ľnde des Welt-Krieges unseres Jahrhunderts. Langen M√ľller, 1989. ISBN 3784422802

- Koepke, Hermann. Encountering the Self. New York, NY: Steiner Books, 1989. ISBN 0880102799

- McDermott, Robert. The Essential Steiner. New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1984. ISBN 0060653450

- Rist, Georg, and Peter Schneider. Integrating Vocational and General Education: A Rudolf Steiner School. Hamburg: Unesco Institute for Education, 1979. ISBN 9282010244

- Solovyov, Vladimir. The Crisis of Western Philosophy. Great Barrington, MA: Lindisfarne, 1996. ISBN 0940262738

- Werner, Uwe. Anthroposophen in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus. Munich, 1999. ISBN 3486563629

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- Defending Steiner

- Rudolf Steiner Web

- Association of Waldorf Schools of North America

- Steiner schools 'could help all' BBC News story on 2005 UK study

- Steiner Schools in England British governmental Department for Education and Skills review of Waldorf schools

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Rudolf_Steiner  history

- Waldorf_Education  history

- Social_Threefolding  history

- Eurythmy  history

- Anthroposophy  history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.