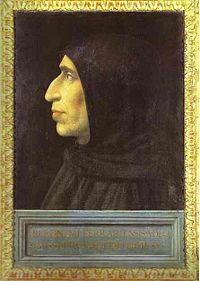

Alexander VI

Pope Alexander VI (January 1, 1431 – August 18, 1503), born Rodrigo Borja (Italian: Rodrigo Borgia), Pope from 1492 to 1503), is the most controversial of the Popes of the Renaissance, whose surname became a byword for low standards in the papacy of that era. More interested in wealth and power than in theology or spirituality, he was in reality a secular and not a religious leader. He was born at Xàtiva, València, Spain, and his father's surname was Lanzol or Llançol; that of his mother's family, Borgia or Borja, was assumed by him on the elevation of his maternal uncle to the papacy as Pope Calixtus III (1455 –1458) on April 8, 1455. Appointed by Calixtus to the College of Cardinals at the age of 26, he was one of many of Calixtus' relatives from Spain who were invited to take up important and lucrative posts in Rome. At age 27, Rodrigo was made vice-chancellor of the Vatican. When Calixtus died in 1458 to be succeeded by Pius II Rodrigo's brother, who had even more illustrious titles including 'prefect of Rome' was literally chased out of Rome. Rodrigo survived and by his 40s was one of the richest Cardinals in a College that contained Europe's wealthiest men. In 1484 he expected to be elected Pope but was by-passed for Innocent VIII. Then in 1492 he literally bought the papacy.

He was renowned for his mistresses but also for his patronage of the arts. He had those he saw as enemies poisoned. The political power of the papacy had declined, and most of Alexander's efforts aimed to restore this but also to protect the remaining papal territories from external threat. Both France and various Italian principalities represented real threats. To offer them an alternative prey, he engineered an alliance against the Ottomans with the real aim of getting the French out of Italy. The Sultan's brother, a hostage, had actually been one of his court favorites.

His main goal in life appears to have been to elevate his own family (including his children) to whom he gave away papal property as will as well as appointing them to senior posts. It is difficult to salvage anything positive from Alexander's legacy. The office he held should have given the Catholic world spiritual leadership; instead, he used it to promote his family's interests and to show kings that earthly treasure is to be accumulated and enjoyed. He rarely if ever gave a thought to the poor, or to the rights of the Amer-Indians, whose lands he gave away to Spain and Portugal ("Papal Bull Inter Caetera May 4, 1493"). Perhaps one of the immediate legacies of this Pope's papacy was the Protestant Reformation, instigated in 1517 by Martin Luther for whom the wealth of the church and the conduct of its leaders was immoral.

Education and election

Rodrigo Borgia studied law at Bologna. He was reputed to have committed his first murder at the age of twelve.[1]. After his uncle's election as Pope he was created successively bishop, Cardinal and vice-chancellor of the church, an act of nepotism characteristic of the age. He served in the Curia under five Popes (Calixtus III, Pius II, Paul II, Sixtus IV and Innocent VIII) and acquired much administrative experience, influence and wealth, although no great power. Like many other prelates of the day, his morals were infamous, his two dominant passions being greed of gold and love of women, and he was devoted to the ten known children his mistresses bore him.

An example of the extreme levels of corruption and immorality then present in the papacy was the Banquet of Chestnuts, also known as the Joust of the Whores, an episode famous in the history of pornography. Although ecclesiastical corruption was then at its height, his riotous mode of life called down upon him a mild reprimand from Pope Pius II (1458– 1464), who succeeded Calixtus III in 1458 On the death of Pope Innocent VIII (1484–1492), the three likely candidates for the Holy See were Cardinals Borgia, Ascanio Sforza and Giuliano della Rovere. While there was never substantive proof of simony, the rumor was that Borgia by his great wealth succeeded in buying the largest number of votes, including that of Sforza, whom he bribed with four mule loads of silver.[2] John Burchard, the conclave's Master of Ceremonies and a leading figure of the Papal Household under several Popes, recorded in his diary that the 1492 conclave was a particularly expensive campaign. Della Rovere was bankrolled to the cost of 200,000 gold ducats by the King of France, with another 100,000 supplied by the Republic of Genoa.[3] Borgia was elected on August 11 1492, assuming the name of Alexander VI.

Nepotism and opposition

Alexander VI's elevation did not at the time excite much alarm, and at first his reign was marked by a strict administration of justice and an orderly method of government in satisfactory contrast with the anarchy of the previous pontificate, as well as by great outward splendor. But it was not long before his unbridled passion for endowing his relatives at the expense of the Church and of his neighbors became manifest. For this object he was ready to commit any crime and to plunge all Italy into war. Alexander VI had four children by his mistress (Vannozza dei Cattani), three sons and a daughter: Giovanni (1474), Cesare, Goffredo (or Giuffre) and Lucrezia Borgia. Cesare, then a youth of seventeen and a student at Pisa, was made archbishop of Valencia, Giovanni received a cardinal's hat in addition to the dukedom of Gandia. For the dukes of Gandia and Giuffre the Pope proposed to carve fiefs out of the papal states and the kingdom of Naples. Among the fiefs destined for the duke of Gandia were Cerveteri and Anguillara, lately acquired by Virginio Orsini, head of that powerful and turbulent house, with the pecuniary help of Ferdinand II of Aragon (1504 – 1516), King of Naples. This brought the latter into conflict with Alexander VI, who determined to revenge himself by making an alliance with the King's enemies, especially the Sforza family, lords of Milan. Alexander did not pause to consider the rights of the Indians who already occupied America, just as he gave no thought to the poor of the world, although Jesus (whose vicar he claimed to be) called them "blessed."

In this he was opposed by Cardinal della Rovere, whose candidature for the papacy had been backed by Ferdinand II. Della Rovere, feeling that Rome was a dangerous place for him, fortified himself in his bishopric of Ostia at the Tiber's mouth, while Ferdinand II allied himself with Florence, Milan, Venice, and the Pope formed a league against Naples (April 25, 1493) and prepared for war. Ferdinand II appealed to Spain for help; but Spain was anxious to be on good terms with the Pope to obtain a title over the newly discovered continent of America and could not afford to quarrel with him. The title was eventually divided between Spain and Portugal along a Demarcation Line and duly granted in the Bull Inter caetera, May 4, 1493. This and other related bulls are known collectively as the Bulls of Donation. The bull authorized the conquest of barbarous nations as long as their peoples were evangelized. Alexander VI mediated great marriages for his children. Lucrezia had been promised to the Spaniard Don Gasparo de Procida, but on her father's elevation to the papacy the engagement was cancelled, and in 1493 she was married to Giovanni Sforza, lord of Pesaro, the ceremony being celebrated at the Vatican Palace with unparalleled magnificence.

But in spite of the splendors of the court, the condition of Rome became every day more deplorable. The city swarmed with Spanish adventurers, assassins, prostitutes and informers; murder and robbery were committed with impunity, and the Pope himself shamelessly cast aside all show of decorum, living a purely secular and immoral life, and indulging in the chase, dancing, stage plays and indecent orgies. One of his close companions was Cem, the brother of the Sultan Bayazid II (1481 –1512), detained as a hostage. The general political outlook in Italy was of the gloomiest, and the country was on the eve of the catastrophe of foreign invasion. At Milan, Lodovico Sforza (il Moro) ruled, nominally as regent for the youthful duke Gian Galeazzo, but really with a view to making himself master of the state.

French involvement

Alexander VI made many alliances to secure his position, but fearing himself isolated he sought help from Charles VIII of France (1483–98). As the King of Naples threatened to come to the aid of Gian Galeazzo, who had married the Pope's granddaughter, Alexander VI encouraged the French King in his schemes for the conquest of Naples. Alexander VI carried on a double policy, always ready to seize opportunities to aggrandize his family. But through the intervention of the Spanish ambassador he made peace with Naples in July 1493 and also with the Orsini; the peace was cemented by a marriage between the Pope's son Giuffre and Doña Sancha, Ferdinand II's granddaughter. In order to dominate the College of Cardinalsmore completely he created twelve new cardinals, among them his own son Cesare, then only eighteen years old, and Alessandro Farnese (later Pope Paul III), the brother of the beautiful Giulia Farnese, one of the Pope's mistresses, creations which caused much scandal. On the January 25, 1494 Ferdinand II died and was succeeded by his son Alphonso II of Naples (1494 C.E.–95 C.E.).

Charles VIII of France now advanced formal claims on the kingdom, and Alexander VI drew him to his side and authorized him to pass through Rome ostensibly on a crusade against the Ottoman Empire, without mentioning Naples. But when the French invasion became a reality he was alarmed, recognized Alphonso II as King, and concluded an alliance with him in exchange for various fiefs for his sons (July 1494). Preparations for defense were made; a Neapolitan army was to advance through the Romagna and attack Milan, while the fleet was to seize Genoa, but both expeditions were badly conducted and failed, and on the eighth of September Charles VIII crossed the Alps and joined Lodovico il Moro at Milan. The papal states were in turmoil, and the powerful Colonna faction seized Ostia in the name of France. Charles VIII rapidly advanced southward, and after a short stay in Florence, set out for Rome (November 1494).

Alexander VI appealed to Ascanio Sforza for help, and even to the Sultan. He tried to collect troops and put Rome in a state of defence, but his position was most insecure, and the Orsini offered to admit the French to their castles. This defection forced the Pope to come to terms, and on the 31st of December Charles VIII entered Rome with his troops and the cardinals of the French faction. Alexander VI now feared that the king might depose him for simony and summon a council, but he won over the bishop of Saint Malo, who had much influence over the King, with a cardinal's hat. Alexander VI agreed to send Cesare, as legate, to Naples with the French army, to deliver Cem to Charles VIII and to give him Civitavecchia (January 16, 1495). On the 28th, Charles VIII departed for Naples with Cem and Cesare, but the latter escaped to Spoleto. Neapolitan resistance collapsed; Alphonso II fled and abdicated in favor of his son Ferdinand II of Naples, who also had to escape, abandoned by all, and the kingdom was conquered with surprising ease.

The French in retreat

But a reaction against Charles VIII soon set in, for all the powers were alarmed at his success, and on March 31, a league between the pope, the emperor, Venice, Lodovico il Moro and Ferdinand of Spain was formed, ostensibly against the Turks, but in reality to expel the French from Italy. Charles VIII had himself crowned King of Naples on May 12, but a few days later began his retreat northward. He encountered the allies at the Battle of Fornovo, and after a drawn fight cut his way through them and was back in France by November; Ferdinand II was reinstated at Naples soon afterwards, though with Spanish help. The expedition, if it produced no material results, demonstrated the foolishness of the so called 'politics of equilibrium' (The Medicean doctrine of preventing one of the Italian principates to overwhelm and unite the rest under its hegemony); since it rendered the country unable to face the ingerences of the powerful 'Nation States' that forged themselves in the previous century (France, Spain). Alexander VI availed himself of the defeat of the French to break the power of the Orsini, following the general tendency of all the princes of the day to crush the great feudatories and establish a centralized despotism.

Virginio Orsini, who had been captured by the Spaniards, died a prisoner at Naples, and the Pope confiscated his property. But the rest of the clan still held out, and the papal troops sent against them under Guidobaldo, duke of Urbino and the duke of Gandia, were defeated at Soriano (January 1497). Peace was made through Venetian mediation, the Orsini paying 50,000 ducats in exchange for their confiscated lands; the duke of Urbino, whom they had captured, was left by the Pope to pay his own ransom. The Orsini still remained very powerful, and Alexander VI could count on none but his 3,000 Spaniards. His only success had been the capture of Ostia and the submission of the Francophile cardinals Colonna and Savelli. Now occurred the first of those ugly domestic tragedies for which the house of Borgia remained famous. On June 14, the duke of Gandia, lately created duke of Benevento, disappeared; the next day his corpse was found in the Tiber River.

Alexander VI, overwhelmed with grief, shut himself up in Castel Sant'Angelo, and then declared that the reform of the Church would be the sole object of his life henceforth – a resolution that he did not keep. Every effort was made to discover the assassin, and suspicion fell on various highly-placed people. Suddenly the rumor spread that Cesare, the Pope's second son, was the author of the deed, and although the inquiries then ceased and no conclusive evidence has yet come to light, there is every probability that the charge was well founded. No doubt Cesare, who contemplated quitting the Church, was inspired by jealousy of Gandia's influence with the Pope.

Confiscations and Savonarola

Violent and revengeful, he now became the most powerful man in Rome, and even his father quailed before him. As he needed funds to carry out his various schemes, Alexander VI began a series of confiscations, of which one of the victims was his own secretary, in order to enrich him. The process was a simple one: any cardinal, nobleman or official who was known to be rich would be accused of some offense; imprisonment and perhaps murder followed at once, and then the confiscation of his property. The disorganization of the Curia was appalling, the sale of offices became a veritable scandal, the least opposition to the Borgia was punished with death, and even in that corrupt age the state of things shocked public opinion. The story of Alexander VI's relations with Savonarola is told in that article; it is enough to say here that the Pope's hostility was due to the friar's outspoken invectives against papal corruption and to his appeals for a General Council. Alexander VI, although he could not get Savonarola into his own hands, browbeat the Florentine government into condemning the reformer to death (May 23, 1498). The Pope was unable to maintain order in his own dominions; the houses of Colonna and Orsini were at open war with each other, but after much fighting they made peace on a basis of alliance against the Pope.

Thus further weakened, the Pope felt more than ever that he had only his own kin to rely upon, and his thoughts were ever turned on family aggrandizement. He had annulled Lucrezia's marriage with Sforza in 1497, and, unable to arrange a union between Cesare and the daughter of Frederick, King of Naples (who had succeeded Ferdinand II the previous year), he induced the latter by threats to agree to a marriage between the duke of Bisceglie, a natural son of Alphonso II, and Lucrezia. Cesare, who renounced his cardinalate, was sent on a mission to France at the end of the year, bearing a bull of divorce for the new King Louis XII of France (1498 – 1515), in exchange for which he obtained the duchy of Valentinois (hence his title of Duca Valentino) and a promise of material assistance in his schemes to subjugate the feudal princelings of Romagna; he married a princess of Navarre.

Alexander VI hoped that Louis XII's help would be more profitable to his house than that of Charles VIII had been and, in spite of the remonstrances of Spain and of the Sforza, he allied himself with France in January 1499 and was joined by Venice. By the autumn Louis XII was in Italy and expelled Lodovico Sforza from the Milanese. In order to consolidate his possessions still further, now that French success seemed assured, the Pope determined to deal drastically with Romagna, which although nominally under papal rule was divided up into a number of practically independent lordships on which Venice, Milan, and Florence cast hungry eyes. Cesare, nominated gonfaloniere of the Church, and strong in French favor, proceeded to attack the turbulent cities one by one. But the expulsion of the French from Milan and the return of Lodovico Sforza interrupted his conquests, and he returned to Rome early in 1500.

Cesare in the North

This year was a jubilee year, and crowds of pilgrims flocked to the city from all parts of the world bringing money for the purchase of Indulgences, so that Alexander VI was able to furnish Cesare with funds for his enterprise. In the north the pendulum swung back once more and the French reoccupied Milan in April, causing the downfall of the Sforzas, much to Alexander VI's gratification. But there was no end to the Vatican tragedies, and in July the duke of Bisceglie, whose existence was no longer advantageous, was murdered by Cesare's orders; this left Lucrezia free to contract another marriage. The Pope, ever in need of money, now created twelve new cardinals, from whom he received 120,000 ducats, and fresh conquests for Cesare were considered. But while a crusade was talked of, the real object was central Italy, and in the autumn, Cesare, favored by France and Venice, set forth with 10,000 men to complete his interrupted enterprise.

The local despots of Romagna were dispossessed and an administration was set up, which, if tyrannical and cruel, was at least orderly and strong, and aroused the admiration of Machiavelli. On his return to Rome (June 1501) Cesare was created duke of Romagna. Louis XII, having succeeded in the north, determined to conquer southern Italy as well, and concluded a treaty with Spain for the division of the Neapolitan kingdom, which was ratified by the Pope on June 25, Frederick being formally deposed. The French army proceeded to invade Naples, and Alexander VI took the opportunity, with the help of the Orsini, to reduce the Colonna to obedience. In his absence he left Lucrezia as regent, offering the astounding spectacle of a pope's natural daughter in charge of the Holy See. Shortly afterwards he induced Alphonso d'Este, son of the duke of Ferrara, to marry her, thus establishing her as heiress to one of the most important principalities in Italy (January 1502).

About this time a Borgia of doubtful parentage was born, Giovanni, described in some papal documents as Alexander VI's son and in others as Cesare's. As France and Spain were quarreling over the division of Naples and the Campagna barons were quiet, Cesare set out once more in search of conquests. In June 1502 he seized Camerino and Urbino, the news of which capture filled the pope with childish joy. But his military force was uncertain, for the condottieri were not to be trusted. His attempt to draw Florence into an alliance failed, but in July, Louis XII of France again invaded Italy and was at once bombarded with complaints from the Borgia's enemies. Alexander VI's diplomacy, however, turned the tide, and Cesare, in exchange for promising to assist the French in the south, was given a free hand in central Italy. A new danger now arose in the shape of a conspiracy against him on the part of the deposed despots, the Orsini and some of his own condottieri. At first the papal troops were defeated and things looked black for the house of Borgia.

Last years

A promise of French help at once forced the confederates to come to terms, and Cesare by an act of treachery seized the ringleaders at Senigallia, and put Oliverotto da Fermo and Vitellozzo Vitelli to death (December 31, 1502). As soon as Alexander VI heard the news he decoyed Cardinal Orsini to the Vatican and cast him into a dungeon, where he died. His goods were confiscated, his aged mother turned into the street and numbers of other members of the clan in Rome were arrested, while Giuffre Borgia led an expedition into the Campagna and seized their castles. Thus the two great houses of Orsini and Colonna, who had long fought for predominance in Rome and often flouted the Pope's authority, were subjugated, and a great step achieved towards consolidating the Borgia's power. Cesare then returned to Rome, where his father wished him to assist Giuffre in reducing the last Orsini strongholds; this for some reason he was unwilling to do, much to Alexander VI's annoyance, but he eventually marched out, captured Ceri and made peace with Giulio Orsini, who surrendered Bracciano.

Three more high personages fell victim to the Borgia's greed this year: Cardinal Michiel, who was poisoned in April 1503, J. da Santa Croce, who had helped to seize Cardinal Orsini, and Troches or Troccio, one of the family's most faithful assassins; all these murders brought immense sums to the Pope. About Cardinal Ferrari's death there is more doubt; he probably died of fever, but Alexander VI immediately confiscated his goods. The war between France and Spain for the possession of Naples dragged on, and Alexander VI was ever intriguing, ready to ally himself with whichever power promised at the moment most advantageous terms. He offered to help Louis XII on condition that Sicily be given to Cesare, and then offered to help Spain in exchange for Siena, Pisa and Bologna. Cesare was preparing for another expedition into central Italy in July 1503, when, in the midst of all these projects and negotiations, both he and his father were taken ill with fever. It is strongly suspected that Cesare inadvertently poisoned his father and himself with wine laced with cantarella (white arsenic) that he probably had intended to use on others,[4] although some sources (including the Encyclopædia Britannica) doubt the stories about poison and attribute the deaths to malaria, at that time very prevalent in Rome.

Death and reputation

Burchard recorded the events that surrounded the death of the Pope. According to Burchard, Alexander VI's stomach became swollen and turned to liquid, while his face became wine-colored and his skin began to peel off. Finally his stomach and bowels bled profusely.

On August 18, 1503 Alexander VI died at the age of 72. His death was followed by scenes of wild disorder, and Cesare, himself apparently ill or poisoned but who survived, could not attend to business, but sent Don Michelotto, his chief bravo, to seize the Pope's treasures before the demise was publicly announced. When the body was exhibited to the people the next day it was in a shocking state of decomposition. Its tongue had swollen and jammed the late Pope's mouth open. Burchard described how the Pope's mouth foamed like a kettle over a fire. The body began to swell so much that it became as wide as it was long. The Venetian ambassador reported that the Alexander VI's body was "the ugliest, most monstrous and horrible dead body that was ever seen, without any form or likeness of humanity".[5] Finally the body began to release sulfurous gasses from every orifice. Burchard records that he had to jump on the body to jam him into the coffin and covered it with an old carpet, the only surviving furnishing in the room.

Such was Alexander VI's unpopularity that the priests of St. Peter's Basilica refused to accept the body for burial until forced to do so by papal staff. Only four prelates attended the Requiem Mass. Alexander's successor on the Throne of Saint Peter, Francesco Todeschini-Piccolomini, who assumed the name of Pope Pius III (1503), forbade the saying of a Mass for the repose of Alexander VI's soul, saying, "It is blasphemous to pray for the damned." After a short stay, the body was removed altogether from the crypts of Saint Peter's and finally installed in another less well known church. Alexander VI has become almost a mythical character, and countless legends and traditions are attached to his name.

Pope Alexander VI's career is not known for great political ideals and his actions generally do not indicate genius. His one thought was family aggrandizement, and while it is unlikely that he meditated making the papacy hereditary in the house of Borgia, he certainly gave away its temporal estates to his children as though they belonged to him. The secularization of the Church was carried to a pitch never before dreamed of, and it was clear to all Italy that he regarded the papacy as an instrument of worldly schemes with no thought of its religious aspect. During his pontificate the Church was brought to its lowest level of degradation. The condition of his subjects was deplorable, and if Cesare's rule in Romagna was an improvement on that of the local tyrants, the people of Rome have seldom been more oppressed than under the Borgia. Alexander VI was not the only person responsible for the general unrest in Italy and the foreign invasions, but he was ever ready to profit by them. Even if we do not accept all the stories of his murders and poisonings and immoralities as true, there is no doubt that his greed for money and his essentially vicious nature led him to commit a great number of crimes.

For many of his misdeeds his terrible son Cesare was responsible, but of others the pope cannot be acquitted. The one pleasing aspect of his life is his patronage of the arts, and in his days a new architectural era was initiated in Rome with the coming of Donato Bramante. Raphael, Michelangelo, and Pinturicchio all worked for him, as he and his family took great pleasure in the most exquisite works of art.

(Note on numbering: Pope Alexander V is now considered an anti-pope. At the time however, he was not considered as such and so the fifth true Pope Alexander took the official number VI. This has advanced the numbering of all subsequent Popes Alexander by one. Popes Alexander VI-VIII are really the fifth through seventh recognized popes by that name.)

Mistresses and family

Of his many mistresses the one for whom his passion lasted longest was a certain Vannozza (Giovanna) dei Cattani, born in 1442, and wife of three successive husbands. The connection began in 1470, and she bore him four children whom he openly acknowledged as his own: Giovanni Borgia (1498), afterwards duke of Gandia (born 1474), Cesare Borgia (born 1476), Lucrezia Borgia (born 1480), and Goffredo or Giuffre (born 1481 or 1482). His other children – Girolamo, Isabella and Pier Luigi – were of uncertain parentage. Before his elevation to the papacy Cardinal Borgia's passion for Vannozza somewhat diminished, and she subsequently led a very retired life. Her place in his affections was filled by the beautiful Giulia Farnese (Giulia Bella), wife of an Orsini, but his love for his children by Vannozza remained as strong as ever and proved, indeed, the determining factor of his whole career. He lavished vast sums on them and loaded them with every honor. A characteristic instance of the papal court of the time is the fact that Borgia's daughter Lucrezia lived with his mistress Giulia, who bore him a daughter Laura in 1492.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Encyclopaedia Brittanica, 1911 edition.

- Burchard, John. The diary of John Burchard of Strasburg, Bishop of Orta and Civita Castellana: Pontificial master of ceremonies to their Holinesses, Sixtus P.P. IV.; Innocent … III; and P.P. Julius II.; A.D. 1483-1506. Translation by A. H. Matthew. Francis Griffiths, 1910. ASIN B00087VDZ6

- Chamberlin, E. R. The Bad Popes. Dorset Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0880291163

- Duffy, Eamon. Saints & Sinners: A History of the Popes. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, in association with S4C, 1997. ISBN 0300073321

- De Rosa, Peter. Vicars of Christ: The Dark Side of the Papacy. New York, NY: Crown Publishers, 1988. ISBN 0517570270

External links

All links retrieved July 18, 2023.

- Pope Alexander VI Catholic Encyclopedia.

| |||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.