Ahmose I

Ahmose I (sometimes written Amosis I and "Amenes" and meaning The Moon is Born) was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the founder of the Eighteenth dynasty. He was a member of the Theban royal house, the son of pharaoh Tao II Seqenenre and brother of the last pharaoh of the Seventeenth dynasty, King Kamose. Sometime during the reign of his father or grandfather, Thebes rebelled against the Hyksos, the rulers of Lower Egypt. When he was seven his father was killed, and when he was about ten when his brother died of unknown causes, after reigning only three years. Ahmose I assumed the throne after the death of his brother, and upon coronation became known as Neb-Pehty-Re (The Lord of Strength is Re).

During his reign he completed the conquest and expulsion of the Hyksos from the delta region, restored Theban rule over the whole of Egypt and successfully reasserted Egyptian power in its formerly subject territories of Nubia and Canaan. He then reorganized the administration of the country, reopened quarries, mines and trade routes and began massive construction projects of a type that had not been undertaken since the time of the Middle Kingdom. This building program culminated in the construction of the last pyramid built by native Egyptian rulers. Ahmose's reign laid the foundations for the New Kingdom, under which Egyptian power reached its peak. His reign is usually dated as occurring about 1550–1525 B.C.E.

Family

Ahmose descended from the Theban Seventeenth Dynasty. His grandfather and grandmother, Tao I and Tetisheri, had at least twelve children, including Tao II and Ahhotep. The brother and sister, according to the tradition of Egyptian queens, married; their children were Kamose, Ahmose I and several daughters.[1] Ahmose I followed in the tradition of his father and married several of his sisters, making Ahmose-Nefertari his chief wife.[1] They had several children including daughters Meretamun B, Sitamun A and sons Siamun A, Ahmose-ankh,[2] Amenhotep I and Ramose A[3] (the "A" and "B" designations after the names are a convention used by Egyptologists to distinguish between royal children and wives that otherwise have the same name). They may also have been the parents of Mutneferet A, who would become the wife of later successor Thutmose I. Ahmose-ankh was Ahmose's heir apparent, but he preceded his father in death sometime between Ahmose's 17th and 22nd regnal year.[4][5] Ahmose was succeeded instead by his eldest surviving son, Amenhotep I, with whom he might have shared a short coregency. He captured the Second cataract fortresses.

There was no distinct break in the line of the royal family between the 17th and 18th dynasties. The historian Manetho, writing much later during the Ptolemaic dynasty, considered the final expulsion of the Hyksos after nearly a century and the restoration of native Egyptian rule over the whole country a significant enough event to warrant the start of a new dynasty.[6]

Dates and length of reign

Ahmose's reign can be fairly accurately dated using the Heliacal rise of Sirius in his successor's reign. However, due to disputes over where the observation was made, he has been assigned a reign from 1570–1546, 1560–1537 and 1551–1527 by various sources.[7][8] Manetho gives Ahmose a reign of 25 years and 4 months;[7] this figure is supported by a ‘Year 22’ inscription from his reign at the stone quarries of Tura.[9] A medical examination of his mummy indicates that he died when he was about thirty-five, supporting a 25-year reign if he came to the throne at the age of 10.[7] Alternative dates for his reign (1194 to 1170 B.C.E.) have been suggested by David Rohl, dissenting from the generally accepted dates, but these are rejected by the majority of Egyptologists.[10]

Campaigns

The conflict between the local kings of Thebes and the Hyksos king Apepi Awoserre had started sometime during the reign of Tao II Seqenenre and would be concluded, after almost 30 years of intermittent conflict and war, under the reign of Ahmose I. Tao II was possibly killed in a battle against the Hyksos, as his much-wounded mummy gruesomely suggests, and his successor Kamose (likely Ahmose's elder brother) is known to have attacked and raided the lands around the Hyksos capital, Avaris (modern Tell el-Dab'a).[11] Kamose evidently had a short reign, as his highest attested regnal year is year Three, and was succeeded by Ahmose I. Apepi may have died near the same time. There is disagreement as to whether two names for Apepi found in the historical record are of different monarchs or multiple names for the same king. If, indeed, they were of different kings, Apepi Awoserre is thought to have died at around the same time as Kamose and was succeeded by Apepi II Aqenienre.[4]

Ahmose ascended the throne when he was still a child, so his mother, Ahhotep, reigned as regent until he was of age. Judging by some of the descriptions of her regal roles while in power, including the general honorific "carer for Egypt," she effectively consolidated the Theban power base in the years prior to Ahmose assuming full control. If in fact Apepi Aqenienre was a successor to Apepi Awoserre, then he is thought to have remained bottled up in the delta during Ahhotep's regency, because his name does not appear on any monuments or objects south of Bubastis.[1]

Conquest of the Hyksos

Ahmose began the conquest of Lower Egypt held by the Hyksos starting around the 11th year of Khamudi's reign, but the sequence of events is not universally agreed upon.[12]

Analyzing the events of the conquest prior to the siege of the Hyksos capital of Avaris is extremely difficult. Almost everything known comes from a brief but invaluable military commentary on the back of the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, consisting of brief diary entries,[13] one of which reads, "Regnal year 11, second month of shomu, Heliopolis was entered. First month of akhet, day 23, this southern prince broke into Tjaru."[14]

While in the past this regnal year date was assumed to refer to Ahmose, it is now believed instead to refer to Ahmose's opponent Khamudi, since the Rhind papyrus document calls Ahmose by the inferior title of 'Prince of the South' rather than king or pharaoh, as Ahmose surely would have called himself.[15] Anthony Spalinger, in a Journal of Near Eastern Studies 60 (2001) book review of Kim Ryholt's 1997 book, The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c.1800-1550 B.C.E., notes that Ryholt's translation of the middle portion of the Rhind text chronicling Ahmose's invasion of the Delta reads instead as the "1st month of Akhet, 23rd day. He-of-the-South (i.e. Ahmose) strikes against Sile."[16] Spalinger stresses in his review that he does not wish to question Ryholt's translation of the Rhind text, but instead asks whether:

"…it is reasonable to expect a Theban-oriented text to describe its Pharaoh in this manner? For if the date refers to Ahmose, then the scribe must have been an adherent of that ruler. To me, the very indirect reference to Ahmose—it must be Ahmose—ought to indicate a supporter of the Hyksos dynasty; hence, the regnal years should refer to this monarch and not the Theban [king]."[17]

The Rhind Papyrus illustrates some of Ahmose's military strategy when attacking the delta. Entering Heliopolis in July, he moved down the eastern delta to take Tjaru, the major border fortification on the Horus Road, the road from Egypt to Canaan, in October, totally avoiding Avaris. In taking Tjaru[14] he cut off all traffic between Canaan and Avaris. This indicates he was planning a blockade of Avaris, isolating the Hyksos from help or supplies coming from Canaan.[18]

Records of the latter part of the campaign were discovered on the tomb walls of a participating soldier, Ahmose, son of Ebana. These records indicate that Ahmose I led three attacks against Avaris, the Hyksos capital, but also had to quell a small rebellion further south in Egypt. After this, in the fourth attack, he conquered the city.[19] He completed his victory over the Hyksos by conquering their stronghold Sharuhen near Gaza after a three year siege.[7][20] Ahmose would have conquered Avaris by the 18th or 19th year of his reign at the very latest. This is suggested by "a graffito in the quarry at Tura whereby 'oxen from Canaan' were used at the opening of the quarry in Ahmose's regnal year 22."[21] Since the cattle would probably have been imported after Ahmose's siege of the town of Sharuhen which followed the fall of Avaris, this means that the reign of Khamudi must have terminated by Year 18 or 19 of Ahmose's 25 year reign at the very latest.[21]

Foreign campaigns

After defeating the Hyksos, Ahmose began campaigning in Syria and Nubia. A campaign during his 22nd year reached Djahy in the Levant and perhaps as far as the Euphrates, although the later Pharaoh Thutmose I is usually credited with being the first to campaign that far. Ahmose did, however, reach at least as far as Kedem (thought to be near Byblos), according to an ostracon in the tomb of his wife, Ahmose-Nefertari.[22] Details on this particular campaign are scarce, as the source of most of the information, Ahmose son of Ebana, served in the Egyptian navy and did not take part in this land expedition. However, it can be inferred from archaeological surveys of southern Canaan that during the late sixteenth century B.C.E. Ahmose and his immediate successors intended only to break the power of the Hyksos by destroying their cities and not to conquer Canaan. Many sites there were completely laid waste and not rebuilt during this period—something a Pharaoh bent on conquest and tribute would not be likely to do.[23]

Ahmose I's campaigns in Nubia are better documented. Soon after the first Nubian campaign, a Nubian named Aata rebelled against Ahmose, but was crushed. After this attempt, an anti-Theban Egyptian named Tetian gathered many rebels in Nubia, but he too was defeated. Ahmose restored Egyptian rule over Nubia, which was controlled from a new administrative center established at Buhen.[1] When re-establishing the national government, Ahmose appears to have rewarded various local princes who supported his cause and that of his dynastic predecessors.[24]

Art and Monumental Constructions

With the re-unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under Ahmose I, a renewal of royal support for the arts and monumental construction occurred. Ahmose reportedly devoted a tenth of all the productive output towards the service of the traditional gods,[25] reviving massive monumental constructions as well as the arts. However, as the defeat of the Hyksos occurred relatively late in Ahmose's reign, his subsequent building program likely lasted no more than seven years,[26] and much of what was started was probably finished by his son and successor Amenhotep I.[27]

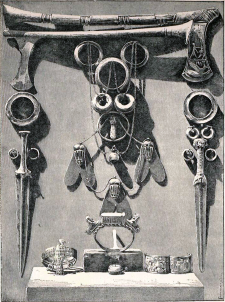

Work from Ahmose's reign is made of much finer material than anything from the Second Intermediate Period. With the Delta and Nubia under Egyptian control once more, access was gained to resources not available in Upper Egypt. Gold and silver were received from Nubia, Lapis Lazuli from distant parts of central Asia, cedar from Byblos,[28] and in the Sinai the Serabit el-Khadim turquoise mines were reopened.[29] Although the exact nature of the relationship between Egypt and Crete is uncertain, at least some Minoan designs have been found on objects from this period, and Egypt considered the Aegean to be part of its empire.[28] Ahmose reopened the Tura limestone quarries to provide stone for monuments.[29]

The art during Ahmose I's reign was similar to the Middle Kingdom royal Theban style,[30] and stelae from this period were once more of the same quality.[29] This reflects a possibly natural conservative tendency to revive fashions from the pre-Hyksos era. Despite this, only three positively identified statuary images of Ahmose I survive: a single shabti kept at the British Museum, presumably from his tomb (which has never been positively located), and two life-size statues; one of which resides in the New Yorker Metropolitan Museum, the other in the Khartoum Museum.[30] All display slightly bulging eyes, a feature also present on selected stelae depicting the pharaoh. Based on style, a small limestone sphinx that resides at the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, has also been tentatively identified as representing Ahmose I.[31]

The art of glassmaking is thought to have developed during Ahmose's reign. The oldest samples of glass appear to have been defective pieces of faience, but intentional crafting of glass did not occur until the beginning of the 18th dynasty.[32] One of the earliest glass beads found contains the names of both Ahmose and Amenhotep I, written in a style dated to about the time of their reigns.[33] If glassmaking was developed no earlier than Ahmose's reign and the first objects are dated to no later than sometime in his successor’s reign, it is quite likely that it was one of his subjects who developed the craft.[33]

Ahmose resumed large construction projects like those before the second intermediate period. In the south of the country he began constructing temples mostly built of brick, one of them in the Nubian town of Buhen. In Upper Egypt he made additions to the existing temple of Amun at Karnak and to the temple of Montu at Armant.[29] He built a cenotaph for his grandmother, Queen Tetisheri, at Abydos.[29]

Excavations at the site of Avaris by Manfred Bietak have shown that Ahmose had a palace constructed on the site of the former Hyksos capital city's fortifications. Bietak found fragmentary Minoan-style remains of the frescoes that once covered the walls of the palace; there has subsequently been much speculation as to what role this Aegean civilization may have played in terms of trade and in the arts.[34]

Under Ahmose I's reign, the city of Thebes became the capital for the whole of Egypt, as it had been in the previous Middle Kingdom. It also became the center for a newly established professional civil service, where there was a greater demand for scribes and the literate as the royal archives began to fill with accounts and reports.[35] Having Thebes as the capital was probably a strategic choice as it was located at the center of the country, the logical conclusion from having had to fight the Hyksos in the north as well as the Nubians to the south. Any future opposition at either border could be met easily.[25]

Perhaps the most important shift was a religious one: Thebes effectively became the religious as well as the political center of the country, its local god Amun credited with inspiring Ahmose in his victories over the Hyksos. The importance of the temple complex at Karnak (on the east bank of the Nile north of Thebes) grew and the importance of the previous cult of Ra based in Heliopolis diminished.[36] Several stelae detailing the work done by Ahmose were found at Karnak, two of which depict him as a benefactor to the temple. In one of these stelae, known as the "Tempest Stele," he claims to have rebuilt the pyramids of his predecessors at Thebes that had been destroyed by a major storm.[37] The Thera eruption in the Aegean Sea has been implicated by some scholars as the source of this damage, but similar claims are common in the propagandistic writings of other pharaohs, showing them overcoming the powers of darkness. Due to a lack of evidence, no definitive conclusion can be reached.

Pyramid

The remains of his pyramid in Abydos were discovered in 1899 and identified as his in 1902.[38] This pyramid and the related structures became the object of renewed research as of 1993 by an expedition sponsored by the Pennsylvania-Yale Institute of Fine Arts, New York University under the direction of Stephen Harvey.[39] Most of its outer casing stones had been robbed for use in other building projects over the years, and the mound of rubble upon which it was built has collapsed. However, two rows of intact casing stones were found by Arthur Mace, who estimated its steep slope as about 60 degrees, based on the evidence of the limestone casing (compare to the less acute 51 degrees of the Great Pyramid of Giza).[40] Although the pyramid interior has not been explored since 1902, work in 2006 uncovered portions of a massive mudbrick construction ramp built against its face. At the foot of the pyramid lay a complex of stone temples surrounded by mud brick enclosure walls. Research by Harvey has revealed three structures to date in addition to the "Ahmose Pyramid Temple" first located by Arthur Mace. This structure, the closest to the base of the pyramid, was most likely intended as its chief cult center. Among thousands of carved and painted fragments uncovered since 1993, several depict aspects of a complex battle narrative against an Asiatic enemy. In all likelihood, these reliefs, featuring archers, ships, dead asiatics and the first known representation of horses in Egypt, form the only representation of Ahmose's Hyksos battles.[39] Adjacent to the main pyramid temple and to its east, Harvey has identified two temples constructed by Ahmose's queen, Ahmose-Nefertary. One of these structures also bears bricks stamped with the name of Chief Treasurer Neferperet, the official responsible for re-opening the stone quarries at el-Ma'asara (Tura) in Ahmose's year 22. A third, larger temple (Temple C) is similar to the pyramid temple in form and scale, but its stamped bricks and details of decoration reinforce that it was a cult place for Ahmose-Nefertary.

The axis of the pyramid complex may be associated with a series of monuments strung out along a kilometer of desert. Along this axis are several key structures: 1) a large pyramid dedicated to his grandmother Tetisheri which contained a stele depicting Ahmose providing offerings to her; 2) a rockcut underground complex which may either have served as a token representation of an Osirian underworld or as an actual royal tomb;[41] and 3) a terraced temple built against the high cliffs, featuring massive stone and brick terraces. These elements reflect in general a similar plan undertaken for the cenotaph of Senwosret III and in general its construction contains elements which reflect the style of both Old and Middle Kingdom pyramid complexes.[41]

There is some dispute as to if this pyramid was Ahmose I's burial place, or if it was a cenotaph. Although earlier explorers Mace and Currelly were unable to locate any internal chambers, it is unlikely that a burial chamber would have been located in the midst of the pyramid's rubble core. In the absence of any mention of a tomb of King Ahmose in the tomb robbery accounts of the Abbott Papyrus, and in the absence of any likely candidate for the king's tomb at Thebes, it is possible that the king was interred at Abydos, as suggested by Harvey. Certainly the great number of cult structures located at the base of the pyramid located in recent years, as well as the presence at the base of the pyramid of a cemetery used by priests of Ahmose's cult, argue for the importance of the king's Abydos cult. However, other Egyptologists believe that the pyramid was constructed (like Tetisheri's pyramid at Abydos) as a cenotaph and that Ahmose may have originally been buried in the southern part of Dra' Abu el-Naga' with the rest of the late 17th and early 18th Dynasties.[29]

This pyramid was the last pyramid ever built as part of a mortuary complex in Egypt. The pyramid form would be abandoned by subsequent pharaohs of the New Kingdom, for both practical and religious reasons. The Giza plateau offered plenty of room for building pyramids; but this was not the case with the confined, cliff-bound geography of Thebes and any burials in the surrounding desert were vulnerable to flooding. The pyramid form was associated with the sun god Re, who had been overshadowed by Amun in importance. One of the meanings of Amun's name was the hidden one, which meant that it was now theologically permissible to hide the Pharaoh's tomb by fully separating the mortuary template from the actual burial place. This provided the added advantage that the resting place of the pharaoh could be kept hidden from necropolis robbers. All subsequent pharaohs of the New Kingdom would be buried in rock-cut shaft tombs in the Valley of the Kings.[42]

Mummy

Ahmose I's mummy was discovered in 1881 within the Deir el-Bahri Cache, located in the hills directly above the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut. He was interred along with the mummies of other 18th and 19th dynasty leaders Amenhotep I, Thutmose I, Thutmose II, Thutmose III, Ramesses I, Seti I, Ramesses II and Ramesses IX, as well as the 21st dynasty pharaohs Pinedjem I, Pinedjem II and Siamun.

Ahmose I's mummy was unwrapped by Gaston Maspero on June 9, 1886. It was found within a coffin that bore his name in hieroglyphs, and on his bandages his name was again written in hieratic script. While the cedarwood coffin's style dates it squarely to the time of the 18th dynasty, it was neither of royal style nor craftsmanship, and any gilding or inlays it may have had were stripped in antiquity.[43] He had evidently been moved from his original burial place, re-wrapped and placed within the cache at Deir el-Bahri during the reign of the 21st dynasty priest-king Pinedjum II, whose name also appeared on the mummy's wrappings. Around his neck a garland of delphinium flowers had been placed. The body bore signs of having been plundered by ancient grave-robbers, his head having been broken off from his body and his nose smashed.[44]

The body was 1.63 m in height. The mummy had a small face with no defining features, though he had slightly prominent front teeth; this may have been an inherited family trait, as this feature can be seen in some female mummies of the same family, as well as the mummy of his descendant, Thutmose II.

A short description of the mummy by Gaston Maspero sheds further light on familial resemblances:

- "…he was of medium height, as his body when mummified measured only 5 feet 6 inches (1.7 m) in length, but the development of the neck and chest indicates extraordinary strength. The head is small in proportion to the bust, the forehead low and narrow, the cheek-bones project and the hair is thick and wavy. The face exactly resembles that of Tiûâcrai [Tao II Seqenenre] and the likeness alone would proclaim the affinity, even if we were ignorant of the close relationship which united these two Pharaohs."[25]

Initial studies of the mummy were first thought to reveal a man in his fifties,[25] but subsequent examinations have shown that he was instead likely to have been in his mid-thirties when he died.[24] The identity of this mummy (Cairo Museum catalog, No. 61057) was called into question in 1980 by the published results of Dr. James Harris, a professor of orthodontics, and Egyptologist Edward Wente. Harris had been allowed to take x-rays of all of the supposed royal mummies at the Cairo Museum. While history records Ahmose I as being the son or possibly the grandson of Sekenenra Tao II, the craniofacial morphology of the two mummies are quite different. It is also different from that of the female mummy identified as Ahmes-Nefertari, thought to be his sister. These inconsistencies, and the fact that this mummy was not posed with arms crossed over chest, as was the fashion of the period for male royal mummies, led them to conclude that this was likely not a royal mummy, leaving the identity of Ahmose I unknown.[45]

The mummy is now in the Luxor Museum alongside the purported one of Ramesses I, as part of a permanent exhibition called "The Golden Age of the Egyptian Military".[46]

Succession

Ahmose I was succeeded by his son, Amenhotep I. A minority of scholars have argued that Ahmose had a short co-regency with Amenhotep, potentially lasting up to six years. If there was a co-regency, Amenhotep could not have been made king before Ahmose's 18th regnal year, the earliest year in which Ahmose-ankh, the heir apparent, could have died.[5] There is circumstantial evidence indicating a co-regency may have occurred, although definitive evidence is lacking.

The first piece of evidence consists of three small objects which contain both of their praenomen next to one another: the aforementioned small glass bead, a small feldspar amulet and a broken stele, all of which are written in the proper style for the early 18th dynasty.[33] The last stele said that Amenhotep was "given life eternally," which is an Egyptian idiom meaning that a king is alive, but the name of Ahmose does not have the usual epithet "true of voice" which is given to dead kings.[33] Since praenomen are only assumed upon taking the throne, and assuming that both were in fact alive at the same time, it is indicated that both were reigning at the same time. There is, however, the possibility that Amenhotep I merely wished to associate himself with his beloved father, who reunited Egypt.

Second, Amenhotep I appears to have nearly finished preparations for a sed festival, or even begun celebrating it; but Amenhotep I's reign is usually given only 21 years and a sed festival traditionally cannot be celebrated any earlier than a ruler's 30th year. If Amenhotep I had a significant co-regency with his father, some have argued that he planned to celebrate his Sed Festival on the date he was first crowned instead of the date that he began ruling alone. This would better explain the degree of completion of his Sed Festival preparations at Karnak.[47] There are two contemporary New Kingdom examples of the breaking of this tradition; Hatshepsut celebrated her Heb Sed Festival in her 16th year and Akhenaten celebrated a Sed Festival near the beginning of his 17-year reign.[48]

Third, Ahmose's wife, Ahmose Nefertari, was called both "King's Great Wife" and "King's Mother" in two stelae which were set up at the limestone quarries of Ma`sara in Ahmose's 22nd year. For her to literally be a "King's Mother," Amenhotep would already have to be a king. It is possible that the title was only honorific, as Ahhotep II assumed the title without being the mother of any known king;[49] though there is a possibility that her son Amenemhat was made Amenhotep I's co-regent, but preceded him in death.[50]

Because of this uncertainty, a co-regency is currently impossible to prove or disprove. Both Redford's and Murnane's works on the subject are undecided on the grounds that there is too little conclusive evidence either for or against a coregency. Even if there was one, it would have made no difference to the chronology of the period because in this kind of institution Amenhotep would have begun counting his regnal dates from his first year as sole ruler.[51][52] However, co-regency supporters note that since at least one rebellion had been led against Ahmose during his reign, it would certainly have been logical to coronate a successor before one's death to prevent a struggle for the crown.[53]

Legacy

Ahmose I is remembered for conquering the Hyksos from the delta region, restoring Theban rule over the whole of Egypt and successfully reasserting Egyptian power in its formerly subject territories of Nubia and Canaan. He also reorganized the administration of the country, reopened quarries, mines and trade routes and began massive construction projects of a type that had not been undertaken since the time of the Middle Kingdom. This building program culminated in the construction of the last pyramid built by native Egyptian rulers. Ahmose's reign laid the foundations for the New Kingdom, under which Egyptian power reached its peak.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Nicolas Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt (Paris: Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988), 190.

- ↑ Aidan Dodson, "Crown Prince Djhutmose and the Royal Sons of the Eighteenth Dynasty." The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 76 (1990).

- ↑ Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt (Thames & Hudson, 2004), 126.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Grimal, 192.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Edward F. Wente, "Thutmose III's Accession and the Beginning of the New Kingdom" Journal of Near Eastern Studies (University of Chicago Press, 1975), 271.

- ↑ Donald B. Redford, History and Chronology of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt: Seven Studies (University of Toronto Press, 1967), 28.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Grimal, 193.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helk, Schwachstellen der Chronologie-Diskussion. (Göttingen: Göttinger Miszellen, 1983), 47–49.

- ↑ James Henry Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Vol. II (University of Chicago Press, 1906), 12.

- ↑ David Rohl, Pharaohs and Kings (Three Rivers Press, 1997, ISBN 0609801309).

- ↑ Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford University Press, 2000), 199.

- ↑ Shaw, 203.

- ↑ Anthony J. Spalinger, War in Ancient Egypt: The New Kingdom (Blackwell Publishing, 2005), 23.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), 128.

- ↑ Thomas Schneider, "The Relative Chronology of the Middle Kingdom and the Hyksos Period (Dyns. 12-17)" in Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David Warburton, (eds), Ancient Egyptian Chronology (Handbook of Oriental Studies) (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 195.

- ↑ Anthony Spalinger, book review of Kim Ryholt's 1997 book, The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c.1800-1550 B.C.E. in Journal of Near Eastern Studies 60(4) (October 2001): 299.

- ↑ Spalinger, 299.

- ↑ Nevine El-Aref, King of the Wild Frontier El Ahram Weekly, November 8, 2005. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ↑ Breasted, 7-8.

- ↑ Redford, 1967, 46–49.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Redford, 1967, 195.

- ↑ James M. Weinstein, "The Egyptian Empire in Palestine, A Reassessment," Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 241 (Winter 1981): 6.

- ↑ Weinstein, 7.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt (The British Museum Press, 1995), 18.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Gaston Maspero, History Of Egypt, Chaldaea, Syria, Babylonia, and Assyria, Volume 4 (of 12) Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ↑ Shaw, 209.

- ↑ Shaw, 213.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Catalogue Général 34001 (Cairo: Egyptian Museum).

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 Grimal, 200.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Edna R. Russman et al., Eternal Egypt: Masterworks of Ancient Art from the British Museum (British Museum, 2001, ISBN 0520230868), 210–211.

- ↑ Edna A. Russman, "Art in Transition: The Rise of the Eighteenth Dynasty and the Emergence of the Thutmoside Style in Sculpture and Relief." Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005, ISBN 1588391736), 24–25.

- ↑ J.D. Cooney, "Glass Sculpture in Ancient Egypt" Journal of Glass Studies 2 (1960):11

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Andrew H. Gordon, "A Glass Bead of Ahmose and Amenhotep I" Journal of Near Eastern Studies 41(4) (October 1982): 296.

- ↑ Shaw, 208.

- ↑ Joyce Tyldesley, Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom (Headline Book Publishing Ltd., 2001), 18–19.

- ↑ Joyce Tyldesley, The Private Lives of the Pharaohs (Channel 4 Books, 2004), 100.

- ↑ Shaw, 210.

- ↑ Egyptian Pharaohs: Ahmose I, phouka.com. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Ahmose Pyramid at Abydos, touregypt.net. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ↑ Mark Lehner, The Complete Pyramids (Thames & Hudson Ltd, 1997, ISBN 0500050848), 190.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Lehner, 1997, 191.

- ↑ Tyldesley, 2004, 101.

- ↑ Dennis C. Forbes, Tombs, Treasures, Mummies: Seven Great Discoveries of Egyptian Archaeology (San Francisco: KMT Communications, Inc. 1998), 614.

- ↑ G. Elliot Smith and Warren Dawson, The Royal Mummies (Duckworth, 2000 (reprint), 15–17.

- ↑ Forbes, 699.

- ↑ Dylan Bickerstaff, Examining the Mystery of the Niagara Falls Mummy KMT 17 (4) (Winter 2006–2007): 31.

- ↑ Wente, 272.

- ↑ Jacques Kinnaer, The Ancient Egypt Site. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ↑ Gordon, 297.

- ↑ Wente, 271.

- ↑ Redford, 1967, 51.

- ↑ William J. Murnane, Ancient Egyptian Coregencies, Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, N° 40. (The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 1977), 114.

- ↑ Gordon, 297.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bickerstaff, Dylan. "Examining the Mystery of the Niagara Falls Mummy." KMT 17 (4) (Winter 2006–2007): 31.

- Breasted, James Henry. Ancient Records of Egypt, Vol. II Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1906. ISBN 9004129898.

- Dodson, Aidan. "Crown Prince Djhutmose and the Royal Sons of the Eighteenth Dynasty." The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 76 (1990).

- Dodson, Aidan, and Dyan Hilton. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, 2004. ISBN 0500051283.

- Forbes, Dennis C. Tombs, Treasures, Mummies: Seven Great Discoveries of Egyptian Archaeology. San Francisco: KMT Communications, Inc., 1998. ISBN 1879388065.

- Gardiner, Alan (Sir). Egypt of the Pharaohs. Oxford University Press, 1964. ISBN 0195002679

- Gordon, Andrew H. "A Glass Bead of Ahmose and Amenhotep I." Journal of Near Eastern Studies 41(4) (October 1982).

- Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988. ISBN 9004129898.

- Helk, Wolfgang. Schwachstellen der Chronologie-Diskussion. Göttingen: Göttinger Miszellen, 1983.

- Lehner, Mark. The Complete Pyramids. Thames & Hudson Ltd, 1997. ISBN 0500050848.

- Murnane, William J. Ancient Egyptian Coregencies, Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, N° 40. (The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 1977

- Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992. ISBN 0691000867.

- Redford, Donald B. History and Chronology of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt: Seven Studies. University of Toronto Press, 1967.

- Rohl, David. Pharaohs and Kings. Three Rivers Press, 1997. ISBN 0609801309.

- Russman, Edna R., "Art in Transition: The Rise of the Eighteenth Dynasty and the Emergence of the Thutmoside Style in Sculpture and Relief." Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh, edited by by Catharine H. Roehrig, Renee Dreyfus, and Cathleen A. Keller. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005. ISBN 1588391736, 24–25.

- Russman, Edna R., et al. Eternal Egypt: Masterworks of Ancient Art from the British Museum. British Museum, 2001. ISBN 0520230868.

- Shaw, Ian. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0198150342.

- Shaw, Ian, and Paul Nicholson. The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. London: The British Museum Press, 1995.

- Smith, G Elliot. The Royal Mummies. Gerald Duckworth & Co Ltd., 2000. ISBN 071562959X.

- Spalinger, Anthony J. War in Ancient Egypt: The New Kingdom. Blackwell Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1405113723.

- Tyldesley, Joyce. Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom. Headline Book Publishing Ltd., 2001. ISBN 0747251606.

- Tyldesley, Joyce. The Private Lives of the Pharaohs. Channel 4 Books, 2004. ISBN 0752219030.

- Weinstein, James M. "The Egyptian Empire in Palestine, A Reassessment." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 241 (Winter, 1981).

- Wente, Edward F. "Thutmose III's Accession and the Beginning of the New Kingdom." Journal of Near Eastern Studies, University of Chicago Press, 1975.

External links

All links retrieved June 16, 2023.

- Maspero, Gaston. History Of Egypt, Chaldaea, Syria, Babylonia, and Assyria, Volume 4 (of 12), Project Gutenberg EBook.

- Ahmose (about 1550-1525 B.C.E.)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.