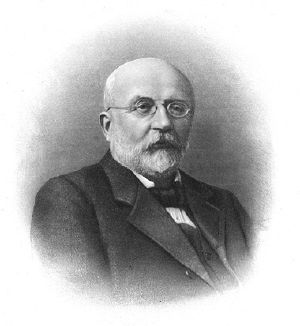

Gaston Maspero

Gaston Camille Charles Maspero (June 23, 1846 - June 30, 1916) was a French Egyptologist who served as director of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, where he established the French School of Oriental Archaeology. Originally trained in linguistics, Maspero began his career translating hieroglyphs. On the death of his colleague, Auguste Mariette, Maspero took over the directorship of excavations in Egypt. He began his work building upon Mariette's findings in Saqqarah, focusing on tombs and pyramids with complete hieroglyphic inscriptions. This work formed the basis of what are now known as the Pyramid Texts. Maspero was also involved in the discovery of a collective royal tomb that contained the mummies of a number of significant pharaohs.

In his work, Maspero encountered looting and was instrumental in apprehending grave robbers. He became involved in fighting against the illegal export of Egyptian antiquities, contributing to the introduction of a series of anti-looting laws, which prevented Egyptian antiques from being taken out of the country. Maspero helped set up a network of local museums throughout Egypt to encourage the Egyptians to take greater responsibility for the maintenance of their own heritage by increasing public awareness within the country. He also introduced many of the artifacts he discovered to the world through his many publications and the establishment of an academic journal and annals for reporting scientific work in Egyptology. In this way, Maspero made significant contributions to the advancement of knowledge and understanding of the history of Ancient Egypt, ensuring that the treasures of this unique and significant civilization would be maintained safely for future generations.

Life

Gaston Maspero was born in Paris, France, to parents of Lombard origin. While at school, he showed a special taste for history and, at the age of 14, was interested in hieroglyphic writing.

It was not until his second year at the Ãcole Normale in 1867, that Maspero met fellow Egyptologist Auguste Mariette, who was then in Paris as commissioner for the Egyptian section of the Exposition Universelle. Mariette gave him two newly discovered hieroglyphic texts of considerable difficulty to study, and Maspero, a self-taught, young scholar was able to translate them rather quickly, a great feat in those days when Egyptology was still almost in its infancy. The publication of those texts in the same year established Maspero's academic reputation.

Maspero then spent a short time in assisting a gentleman in Peru, who was seeking to prove an Aryan connection to the dialects spoken by the Native Americans of that country. In 1868, Maspero was back in France with more profitable work. In 1869, he became a teacher (répétiteur) of Egyptian language and archaeology at the Ãcole Pratique des Hautes Ãtudes and in 1874, he was appointed to the Champollion chair at the Collège de France.

In 1880, Maspero went to Egypt as head of an archaeological team sent by the French government. They eventually established the permanent Mission in Cairo, under the name Institut Français dâArchéologie Orientale. This occurred a few months before the death of Mariette, whom Maspero then succeeded as director-general of excavations and of the antiquities in Egypt.

Aware that his reputation was then more as a linguist than an archaeologist, Maspero's first work in the post was to build on Mariette's achievements at Saqqarah, expanding their scope from the early to the later Old Kingdom. He took particular interest in tombs with long and complete hieroglyphic inscriptions that could help illustrate the development of the Egyptian language. Selecting five later Old Kingdom tombs, he was successful in finding over 4000 lines of hieroglyphics which were then sketched and photographed.

As an aspect of his attempt to curtail the rampant illegal export of Egyptian antiquities by tourists, collectors, and the agents of the major European and American museums, Maspero arrested the Abd al-Russul brothers from the notorious treasure-hunting village of Gorna. They confessed under torture to having found a great cache of royal mummies at Deir el-Bahari in July 1881. The cache, which included mummies of the pharaohs Seti I, Amenhotep I, Thutmose III, and Ramesses II in sarcophagi together with magnificent funerary artifacts, was moved to Cairo as soon as possible to keep it safe from robbers.

In 1886, Maspero resumed work begun by Mariette to uncover the Sphinx, removing more than 65 feet of sand and seeking tombs below it (which were found only later). He also introduced admission charges for Egyptian sites to the increasing number of tourists to pay for their upkeep and maintenance.

In spite of his brutality towards the Abd al-Russul brothers, Maspero was popular with museum keepers and collectors and was known to be a "pragmatic" director of the Service of Antiquities. Maspero did not attempt to halt all collecting, but rather sought to control what went out of the country and to gain the confidence of those who were regular collectors. When Maspero left his position in 1886, and was replaced by a series of other directors who attempted to halt the trade in antiquities, his absence was much lamented.

Maspero resumed his professorial duties in Paris from June 1886, until 1899, when, at 53, he returned to Egypt in his old capacity as director-general of the department of antiquities. On October 3, 1899, an earthquake at Karnak collapsed 11 columns and left the main hall in ruins. Maspero had already made some repairs and clearances there (continued in his absence by unofficial but authorized explorers of many nationalities) in his previous tenure of office, and now he set up a team of workmen under French supervision. In 1903, an alabaster pavement was found in the court of the 7th Pylon and beneath it, a shaft leading to a large hoard of almost 17,000 statues.

Because of the policy of keeping all the items discovered in Egypt, the collections in the Bulak Museum were enormously increased. In 1902, Maspero organized their removal from Giza to the new quarters at Kasr en-Nil. The vast catalogue of the collections made rapid progress under Maspero's direction. Twenty-four volumes or sections were published in 1909. This work and the increasing workload of the Antiquities Service led to an expansion of staff at the museum, including the 17 year old Howard Carter. In 1907, it was Maspero who recommended Carter to Lord Carnarvon when the Earl approached him to seek advice for the use of an expert to head his planned archaeological expedition to the Valley of the Kings.

In 1914, Maspero was elected the permanent secretary of the Académie des inscriptions et belles lettres. He died in June 1916, and was interred in the Cimetière du Montparnasse in Paris.

Work

Saqqarah texts

The pyramid of Unas of the Fifth Dynasty (originally known as Beautiful are the places of Unas) was first investigated by Perring and then Lepsius, but it was Gaston Maspero who first gained entry to the chambers in 1881, where he found texts covering the walls of the burial chambers, these together with others found in nearby pyramids are now known as the Pyramid Texts.

These texts were reserved only for the pharaoh and were not illustrated.[1] The pyramid texts mark the first written mention of the god Osiris, who would become the most important deity associated with afterlife.[2]

The spells, or "utterances," of the pyramid texts are primarily concerned with protecting the pharaoh's remains, reanimating his body after death, and helping him ascend to the heavens, which are the emphasis of the afterlife during the Old Kingdom. The spells delineate all of the ways the pharaoh could travel, including the use of ramps, stairs, ladders, and most importantly flying. The spells could also be used to call the gods to help, even threatening them if they did not comply.[3]

Mummies

Thutmose III's mummy was one of those discovered in the Deir el-Bahri Cache above the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut in 1881. He was interred along with those of other eighteenth and nineteenth dynasty leaders Ahmose I, Amenhotep I, Thutmose I, Thutmose II, Ramesses I, Seti I, Ramesses II, and Ramesses IX, as well as the twenty-first dynasty pharaohs Pinedjem I, Pinedjem II, and Siamun.

It had been extensively damaged in antiquity by tomb robbers, and its wrappings subsequently cut into and torn by the Rassul family when they originally rediscovered the tomb and its contents.[4] Maspero's description of the body provides an idea as to the magnitude of the damage done to the body:

His mummy was not securely hidden away, for towards the close of the 20th dynasty it was torn out of the coffin by robbers, who stripped it and rifled it of the jewels with which it was covered, injuring it in their haste to carry away the spoil. It was subsequently re-interred, and has remained undisturbed until the present day; but before re-burial some renovation of the wrappings was necessary, and as portions of the body had become loose, the restorers, in order to give the mummy the necessary firmness, compressed it between four oar-shaped slips of wood, painted white, and placed, three inside the wrappings and one outside, under the bands which confined the winding-sheet.

Of the face, which was undamaged, Maspero's says the following:

Happily the face, which had been plastered over with pitch at the time of embalming, did not suffer at all from this rough treatment, and appeared intact when the protecting mask was removed. Its appearance does not answer to our ideal of the conqueror. His statues, though not representing him as a type of manly beauty, yet give him refined, intelligent features, but a comparison with the mummy shows that the artists have idealised their model. The forehead is abnormally low, the eyes deeply sunk, the jaw heavy, the lips thick, and the cheek-bones extremely prominent; the whole recalling the physiognomy of Thûtmosis II, though with a greater show of energy.

Maspero was so disheartened at the state of the mummy, and the prospect that all of the other mummies were similarly damaged (as it turned out, few were in as poor a state), that he would not unwrap another for several years.

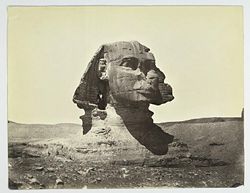

Sphinx

When Maspero surveyed the Great Sphinx he, like some other early Egyptologists asserted that the Sphinx predated Khafre (also known as Chephren):

The Sphinx stela shows, in line thirteen, the cartouche of Khephren. I believe that to indicate an excavation carried out by that prince, following which, the almost certain proof that the Sphinx was already buried in sand by the time of Khafre and his predecessors.[5]

Notwithstanding Maspero's belief, it is commonly accepted by Egyptologists that the Sphinx represents the likeness of Khafre, who is often credited as the builder as well, placing the time of its construction somewhere between 2520 B.C.E. and 2494 B.C.E.

Publications

Among Maspero's best-known publications are the large Histoire ancienne des peuples de l'Orient classique (3 vols., Paris, 1895-1897, translated into English by Mrs. McClure for the S.P.C.K.), displaying the history of the whole of the nearer East from the beginnings to the conquest by Alexander the Great. He also wrote a smaller single volumed Histoire des peuples de l'Orient, of the same time period, which passed through six editions from 1875 to 1904; Etudes de mythologie et d'archéologie égyptiennes (1893), a collection of reviews and essays originally published in various journals, and especially important as contributions to the study of Egyptian religion; L'Archéologie égyptienne (1887), of which several editions have been published in English. He established the journal Recueil de travaux relatifs à la philologie et à l'archéologie égyptiennes et assyriennes; the Bibliothèque égyptologique, in which the scattered essays of the French Egyptologists are collected, with biographies; and the Annales du service des antiquités de l'Egypte, a repository for reports on official excavations.

Maspero also wrote Les inscriptions des pyramides de Saqqarah (Paris, 1894); Les momies royales de Deir el-Bahari (Paris, 1889); Les contes populaires de l'Egypte ancienne (3rd ed., Paris, 1906); and Causeries d'Egypte (1907), translated by Elizabeth Lee as New Light on Ancient Egypt (1908).

Legacy

For over 40 years Maspero was one of the leading figures in Egyptology research. He published a whole series of works which introduced Egyptian culture to the outside world. Maspero also helped set up a network of local museums throughout Egypt to encourage the Egyptians to take greater responsibility for the maintenance of their own heritage by increasing public awareness of it. He succeeded where his predecessors had failed in the introduction of a series of anti-looting laws, preventing Egyptian antiques from being taken out of the country.

Publications

- Maspero, Gaston. 1875. Histoire des peuples de l'Orient. Paris: Hachette.

- Maspero, Gaston. [1882] 2002. Popular Stories of Ancient Egypt (Les contes populaires de l'Egypte ancienne). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1576076393

- Maspero, Gaston. [1884] 2006. The Dawn of Civilization. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0766177742

- Maspero, Gaston. [1887] 2001. L'archéologie égyptienne. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1421217155

- Maspero, Gaston. 1889. Les momies royales de Deir el-Bahari. Paris: E. Leroux.

- Maspero, Gaston. 1893. Etudes de mythologie et d'archéologie égyptiennes. Paris: E. Leroux.

- Maspero, Gaston. 1894. Les inscriptions des pyramides de Saqqarah. Paris: Ã. Bouillon.

- Maspero, Gaston. [1895] 1897. Histoire ancienne des peuples de l'Orient classique. Paris: Hachette.

- Maspero, Gaston. 1907. Causeries d'Egypte. Paris: E. Guilmoto.

- Maspero, Gaston. 2003. Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt and Assyria. London: Kegan Paul International. ISBN 0710308833

Notes

- â Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature (London: University of California Press, 1975).

- â Ogden Goelet, et al., The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2000.) ISBN 978-0811807678

- â James P. Allen, Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000). ISBN 0521774837

- â John Romer, The Valley of the Kings (Castle Books, 2003). ISBN 0-7858-1588-0

- â The Global Education Project, The SphinxâSome History. Retrieved July 30, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allen, James P. Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 0521774837

- David, Elisabeth. Gaston Maspero, 1846-1916 le gentleman égyptologue. Bibliothèque de l'Egypte ancienne. Paris: Pygmalion/G. Watelet, 1999. ISBN 2857045654

- Deuel, Leo. The Treasures of Time; Firsthand Accounts by Famous Archaeologists of Their Work in the Near East. Cleveland: World Pub. Co., 1961.

- Forbes, Dennis C. Tombs, Treasures, Mummies: Seven Great Discoveries of Egyptian Archaeology. KMT Communications, Inc., 1998. ISBN 978-1879388062

- Goelet, Ogden, Carol Andrews, and James Wasserman. The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day. Chronicle Books, 2000. ISBN 978-0811807678

- Jastrow, Morris. Sir Gaston Maspero. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1916.

- Lichtheim, Miriam. Ancient Egyptian Literature. London: University of California Press, 1975. ISBN 0520028996

- Romer, John. The Valley of the Kings. New York: Castle Books, 2003. ISBN 0785815880

External links

All links retrieved April 17, 2024.

- L'archéologie égyptienne â Full-text Masperoâs work on Project Gutenberg.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.