Yahweh

Yahweh1 (ya·'we) in the Bible, the God of Israel. "Jehovah" is a modern mispronunciation of the Hebrew name, resulting from combining the consonants of that name, Yhwh (formerly transcribed 'JHVH'), with the vowels of the word Adonai, Lord, which the Jews substituted for the proper name in reading the scriptures. In such cases of substitution the vowels of the word which is to be read are written in the Hebrew text with the consonants of the word which is not to be read (see Q're perpetuum). The consonants of the word to be substituted are ordinarily written in the margin; but inasmuch as Adonai was regularly read instead of the ineffable name YHWH, it was deemed unnecessary to note the fact at every occurrence. When Christian scholars began to study the Old Testament in Hebrew, if they were ignorant of this general rule or regarded the substitution as a piece of Jewish superstition, reading what actually stood in the text, they would inevitably pronounce the name Jehova. It is an unprofitable inquiry who first made this blunder; probably many fell into it independently. The statement still commonly repeated that it originated with Petrus. These details are scarcely the invention of the chronicler; see CHRONICLES, and Expositor, Aug. 1906, p. 191.

1Though the original pronunciation of the consonantally-written name YHWH is not known with certainty, linguistic scholars generally consider Yahwheh to be most probable, and this form is the one generally used in the separate articles throughout this encyclopedia. (See: Wikisource:Yahweh)

Tetragrammaton

The Tetragrammaton (Greek: τετραγράμματον; "word with four letters") is the usual reference to the Hebrew name for God, which is spelled (in the Hebrew alphabet): י (yodh) ה (heh) ו (vav) ה (heh) or יהוה (YHWH). It is the distinctive personal name of the God of Israel.

Of all the names of God, the one which occurs most frequently in the Hebrew Bible is the Tetragrammaton, appearing 6,823 times, according to the Jewish Encyclopedia. The Biblia Hebraica and Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia texts of the Hebrew Scriptures each contain the Tetragrammaton 6,828 times.

In Judaism, the Tetragrammaton is the ineffable name of God, and is therefore not to be read aloud. In the reading aloud of the scripture or in prayer, it is replaced with Adonai ("My Lords", commonly rendered as "the Lord"). Other written forms such as י (yod) ו (vav) (YW or Yaw); or י (yod) ה (heh) (YH or Yah) are read in the same way.

Outside of direct prayer, the word "’ǎdônây" (אֲדֹנָי) is not spoken by some Jews since to do so is considered a violation of the commandment not to use the Lord's name in vain (Exodus 20:7). Therefore, the word is often read as HaShêm (הַשֵּׁם) literally, "The Name") or in some cases ’ǎdô-Shêm, a composite of ’ǎdônây and HaShêm. A similar rule applies to the word ’ělôhîym ("God"), which some Jews intentionally mispronounce as ’ělôkîym for the same reason. (In a process analogous to the "euphemism treadmill", a prosaic substitute for the Tetragrammaton during one historical period may acquire sanctity and thus itself be considered too holy for ordinary use in subsequent periods.)

Meaning

According to one Jewish tradition, the Tetragrammaton is related to the causative form, the imperfect state, of the Hebrew verb הוה (ha·wah, "to be, to become"), meaning "He will cause to become" (usually understood as "He causes to become"). Compare the many Hebrew and Arabic personal names which are 3rd person singular imperfective verb forms starting with "y", e.g. Hebrew Yôsêph = Arabic Yazîd = "He [who] adds"; Hebrew Yiḥyeh = Arabic Yahyâ = "He [who] lives".

Another tradition regards the name as coming from three different verb forms sharing the same root YWH, the words HYH haya היה: "He was"; HWH howê הוה: "He is"; and YHYH yihiyê יהיה: "He will be". This is supposed to show that God is timeless, as some have translated the name as "The Eternal One". Other interpretations include the name as meaning "I am the One Who Is." This can be seen in the traditional Jewish account of the "burning bush" commanding Moses to tell the sons of Israel that "I AM אהיה has sent you." (Exodus 3:13-14) Some suggest: "I AM the One I AM" אהיה אשר אהיה, or "I AM whatever I need to become". This may also fit the interpretation as "He Causes to Become." Many scholars believe that the most proper meaning may be "He Brings Into Existence Whatever Exists" or "He who causes to exist".

The name YHWH was not always applied to a monotheistic God: see Asherah and other gods, Elohim (gods) and Yaw (god).

Transcription

Using consonants as semi-vowels

In Biblical Hebrew, most vowels are not written and the rest are written only ambiguously, as the vowel letters double as consonants (similar to the Latin use of V to indicate both U and V). See Matres lectionis for details. For similar reasons, an appearance of the Tetragrammaton in ancient Egyptian records of the 13th century B.C.E. sheds no light on the original pronunciation. 2. Therefore it is, in general, difficult to deduce how a word is pronounced from its spelling only, and the Tetragrammaton is a particular example: two of its letters can serve as vowels, and two are vocalic place-holders, which are not pronounced. Not surprisingly then, Josephus in Jewish Wars, chapter V, wrote, "…in which was engraven the sacred name: it consists of four vowels". In Greek, they are Ιαου, which comes out to Yau, since iota is used to represent semi-vocalic 'y' (and omicron+ypsilon="oo").

Further, Josephus's four vowels are confirmed by theophoric stems in personal names, always: Yaho/Yahu/Y:ho/Y:hu.[1] These yield in English Yau and Yao, which are pronounced the same. Once again, the heh is not pronounced here in Hebrew, but is used instead as a place holder. Moreover, Gnostic texts, such as those Marcion wrote, discuss the Judaic god extensively, and spell the Tetragrammaton in Greek, Ιαω, that is "Yao." Lastly, Levantine texts (including those from ancient Ugarit) render the Tetragrammaton Yaw, pronounced "Yau."[2]

Vowel marks

To make the reading of Hebrew easier, marks or points above and below the letters were added to the text by the Masoretes, to function as vowels. See Niqqud for details. Several manuscripts from the 7th century and on contain vowel marks over the Tetragrammaton. Unfortunately, these do not shed much light on the pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton. For example, the Leningrad codex contains six different variations on the vowel marks of the Tetragrammaton.

An added problem is that the diacritical vowel marks on the Tetragrammaton may have served a purpose other than indicating the pronunciation. When the text is read out loud by Jews, the Tetragrammaton is replaced by the word Adonai ("my Lord(s)"), Elohim ("God(s)"), Hashem ("the name"), or Elokim (no meaning), depending on circumstances (see Jewish use of the word below). Since someone reading the text aloud might inadvertently pronounce the name, the diacritical vowels of Adonai or Elohim are normally printed with the consonant letters of the Tetragrammaton, to remind the reader to make the change, so the text contains the letters YHWH interlaced with the vowel marks of Adonai/Elohim (a masoretic device known as Q're perpetuum which was also applied in a number of other cases, such as giving the spelling הוא in the Pentateuch an "i" vowel diacritic to indicate that sometimes it should be pronounced as a feminine pronoun hi, rather than a masculine pronoun hu). This is the case in modern editions of the Hebrew Bible, and also explains a number of medieval codices. In other words, these marks do not and were never intended to explain how to pronounce the Tetragrammaton.

In particular, there is a possible explanation of the vowel marks on the Tetragrammaton in the Ben Chayim codex of 1525 (see its importance below). It is worth noting that the aleph in Adonai has a hataf-patah (pronounced "ah" in Modern Hebrew) under it while the yod in the Tetragrammaton has a sheva (pronounced as a very short "eh" in Modern Hebrew).

- Note that in the image above and to the right, "YHWH intended to be pronounced as Adonai" [i.e. "יְהוָֹה"] and "Adonai with its slightly different vowel points" [i.e. "אֲדֹנָי"] do not have the precise same vowel points.

- In other words, the Masoretes did not point YHWH with the precise vowel points of Adonai.

This can be explained by rules of Hebrew grammar, which forbid a sheva under an aleph, although this explanation is not entirely satisfactory.

Sir Godfry Driver wrote: "The Reformers preferred Jehovah, which first appeared as Iehouah in A.D. 1530 in Tyndale's translation of the Pentateuch (Exodus 6.3), from which it passed into other Protestant Bibles." The English transcription "Iehovah", is found in the 1611 edition of the King James Bible, and during the 1762-1769 edit of the KJV, the spelling "Iehovah" was changed to "Jehovah" (in accordance with the general differentiation of I/J and U/V into separate letters which developed over the course of the 17th century in English). Thus began a period where the word was rendered: "Jehovah". The Jerusalem Bible (1966) uses Yahweh exclusively.

Yahweh

19th Century scholars disputed the vowel points of "יְהוָֹה"

Wilhelm Gesenius [1786-1842], who is noted for being one of the greatest Hebrew and biblical scholars, 3 wrote a Hebrew Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament which was first translated into English in 1824. 4 In the first half of the 19th century, Wilhelm Gesenius, as well as many other scholars, believed that the Medieval vowel points of "יְהֹוָה" were not the actual vowel points of God’s name.

Wilhelm Gesenius Punctuated YHWH as "יַהְוֶה" (i.e. Yahweh)

In Smith's " A Dictionary of the Bible" [published in 1863] William Smith notes 5 that Wilhelm Gesenius punctuated YHWH as "יַהְוֶה" (see image to the right)

This vocalized Hebrew spelling of the Tetragrammaton "יַהְוֶה" ( i.e. Yahweh ), is sometimes referred to as a "Scholarly Reconstruction" and is believed to have been based in large part on various Greek transcriptions, such as (ιαουε—iaoue and ιαουαι—iaouai and ιαβε—Iabe) dating from the first centuries AD.

"יַהְוֶה" [i.e. Yahweh] may have represented Epiphanius's "Iαβε"

In Smith's 1863 " A Dictionary of the Bible", William Smith supposes that "יַהְוֶה" was represented by the "Iαβε" of Epiphanius. 8

The Catholic Encyclopedia of 1910 says: Inserting the vowels of Jabe [e.g. Latin form of Iabe] into the Hebrew consonant text, we obtain the form Jahveh (Yahweh), which has been generally accepted by modern scholars as the true pronunciation of the Divine name;9.

Scholarly sources in which "יַהְוֶה" is found

Smith's 1863 C.E. A Dictionary of the Bible

In Smith's 1863 "A Dictionary of the Bible", William Smith does not consider "יַהְוֶה" to be the best scholarly reconstructed vocalized Hebrew spelling of the Tetragrammaton which he is aware of.

However, although "יַהְוֶה" was not the only scholarly reconstructed vocalized Hebrew spelling of the Tetragrammaton that appeared in scholarly sources in the 19th century, it gradually became accepted as the best scholarly reconstructed vocalized Hebrew spelling of the Tetragrammaton.

The Jewish Encyclopedia of 1901-1906 C.E.

The editors of the Jewish Encyclopedia of 1901-1906 recognize that "יַהְוֶה" is spelled "Yahweh" in English, but "יַהְוֶה" is only one of two vocalized Hebrew spellings, that they believe might have been the original pronunciation of YHWH. In the Article:Names of God, and under the article sub heading: "YHWH", the editors write:

- If the explanation of the form above given be the true one, the original pronunciation must have been Yahweh (יַהְוֶה) or Yahaweh (יַהֲוֶה). From this the contracted form Jah or Yah (יהּ ) is most readily explained, and also the forms Jeho or Yeho ( יַהְוְ = יְהַו = יְהוֹ ), and Jo or Yo ( יוֹ contracted from יְהוֹ ), which the word assumes in combination in the first part of compound proper names, and Yahu or Yah ( יָהוּ = (image) in the second part of such names.

The early 1900's Brown-Driver-Briggs Lexicon

The editors of the Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament write "יַהְוֶה" under the heading "יהוה", and describes "יַהְוֶה" as:

- "n.pr.dei Yahweh, the proper name of the God of Israel."

Jewish use of the word

In Judaism, pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton is a taboo; it is widely considered forbidden to utter it and the pronunciation of the name is generally avoided. Usually, Adonai is used as a substitute in prayers or readings from the Torah. When used in everyday speaking (or according to many) in learning the Tetragrammaton is replaced by HaShem. The difference is marked by the vowelization in printed Bibles—the Tetragrammaton takes on the vowels of the word whose pronunciation it takes. Torah scrolls have no diacritical vowel marks, and therefore the reader must memorize the correct pronunciation for each instance of the Tetragrammaton (as for every word he reads).

According to rabbinic tradition, the name was pronounced by the high priest on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement as well as the only day when the Holy of Holies of the Temple would be entered. With the destruction of the Second Temple in the year 70, this use also vanished, also explaining the loss of the correct pronunciation. (In one midrashic tradition, only seven Cohanim, or individuals of priestly lineage, know the true name of God, and it is passed down throughout the generations to be ready for invocation during the building of the Third Jewish Temple.)

There is a Jewish tradition that the actual name of God, only known to and stated by the high priest, was actually 72 letters long. The name was written out on a long strip of parchment, then folded and slipped inside the fold of the high priest's bejeweled breastplate. When someone would ask the high priest a question of Torah, or Jewish law, the high priest could invoke the Name, wherein the 12 jewels, representing the 12 tribes of the Israelites, would light up in a certain order whose meaning was, too, only known to the high priest. Through the power of the 72-letter name of God, the high priest communed, as it were, with the Almighty.

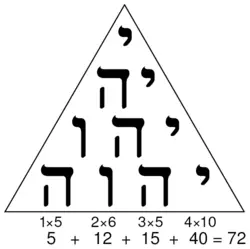

Why 72 letters? The answer may be found in the medieval rabbinic use of Gematria, that is assigning a number to each letter of the Hebrew alphabet, allowing scholars to attribute numeric sums to words, find equivalencies in certain words, even use sums to try to predict a year and date for the coming of the Messiah. Even today, Jews often attribute mystical significance to the number 18, which has a possible Hebrew letter equivalent in the word "Chai", meaning "Life". Using "Gematria", we find that "Chai" equals 18: it's composed of the letter "chet", which equals 8, and the letter "yod", which equals 10, i.e. 8+10=18; consequently 18x4=72, so, in a sense, each letter of the 4-letter form of the Name represents a metaphoric symbol of the living power of God. Also, when the letters of the Tetragrammaton are arranged in a Kabbalistic tetractys formation, the sum of all the letters is 72 by Gematria (as shown in the diagram). Keeping along these lines, the Tetragrammaton, since it's only an abbreviation of the actual name, is not as powerful by nature (or supernature) as the original full name of God, though it's still not something to use in vain.

When most religious Jews refer to the name of God in conversation or in a non-textual context such as in a book, newspaper or letter, they call the name HaShem, which means "the Name." Similarly, the word Elohim is prononuced "Elokim" outside of certain religious contexts when it refers to God, and likewise for a few other names of God. When any such word is used to refer to anything but God (e.g., HaShem), it is pronounced as normal by even the most traditionalist Jews.

A number of modern translations of the Hebrew Bible and of Jewish liturgy render the Tetragrammaton as "the ETERNAL" (emphasized or all caps), because it is gender-neutral (unlike "The Lord"). The Hebrew letters of the Tetragrammaton are the only ones required to write the Hebrew sentence "haya, hove, ve-yiheyeh" (He was, He is, and He shall be), hence "Eternal."

Alternative names

In an analogue to the euphemism HaShem for God, the euphemism HaShem HaMeforash (literally, the explicit name) is sometimes used to refer to the Tetragrammaton.

Another name, four-letter word, has lost its popularity for obvious reasons. Some people refer to the Tetragrammaton as Hebrew word #3068 after the numbering in James Strong's concordance. See also The name of God in Judaism.

Possible origins

A common suggestion, as articulated by biblical scholar Mark S. Smith in The Origins of Biblical Monotheism, is that the Israelite Yahweh was derived from the traditions of the Shasu, linguistically Canaanite nomads from southern transjordan. An Egyptian inscription from the Temple of Amun at Karnak from the time of Pharaoh Amenhotep III (1390-1352 B.C.E.) refers to the "Shasu of Yhw," evidence that this god was worshipped among some of the Shasu tribes at this time. Biblical archaeologist Amihai Mazar, in Archaeology of the Land of the Bible Volume I, suggests that the association of Yahweh with the desert may be the product of his origins in the dry lands to the south of Israel. Egyptologist Donald Redford, in Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, suggests that the Israelites themselves may have been a group of Shasu who moved northward into Canaan in the 13th century B.C.E., appearing for the first time in the stele of Merenptah, and as Israel Finkelstein has shown in The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts settled the Samarian and Judean hills at this time.

Van der Toorn's article "Yahweh" in the Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible notes that, although a wide range of opinions have been presented, no clear etymology for the tetragrammaton presents itself.

Hebraist Joel M. Hoffman, in Chapter 4 of In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language, argues that the Tetragrammaton was purposely composed only and entirely of matres lectiones. (See also Elohim.)

Usage

Among Reformers

Galatinus (1518) is erroneous; Jehova occurs in manuscripts at least as early as the I4th century.

The form Jehovah was used in the 16th century by many authors, both Catholic and Protestant, and in the 17th was zealously defended by Fuller, Gataker, Leusden and others, against the criticisms of such scholars as Drusius, Cappellus and the elder Buxtorf. It appeared in the English Bible in Tyndale's translation of the Pentateuch (1530), and is found in all English Protestant versions of the 16th century except that of Coverdale (535). In the Authorized Version of 1611 it occurs in Exod. vi. 3; Ps. lxxxiii; Isa. Xii. xxvi. 4, beside the compound names Jehovah-jireh, Jehovah-nissi, Jehovah-shalom; elsewhere, in accordance with the usage of the ancient versions, Yhwh is represented by Lord (distinguished by capitals from the title Lord. Heb. adonai). In the Revised Version of 1885 Jehovah is retained in the places in which it stood in the A. V., and is introduced also in Exod. vi. 2, 6, 7, 8; Ps. lxviii. 20; Isa. xlix. 14; Jer. XVI. 21; Hab. iii. 19. The American committee which cooperated in the revision desired to employ the name Jehovah wherever Yhwh occurs in the original, and editions embodying their preferences are printed accordingly.

In ancient Judaism

Several centuries before the Christian era the name Yhwh had ceased to be commonly used by the Jews. Some of the later writers in the Old Testament employ the appeliative Elohim, God, prevailingly or exclusively: a collection of Psalms (Ps. xlii. lxxxiii.) was revised by an editor who changed the Yhwh of the authors into Elohim (see e.g. xlv. 7; xlviii. 10; 1. 7; ii. 14); observe also the frequency of the Most High, the God of Heaven, King of Heaven, in Daniel, and of Heaven in First Maccabees. The oldest Greek versions (Septuagint), from the third century B.C.E., consistently use Kyrie, Lord, where the Hebrew has Yhwh, corresponding to the substitution of Adonay for Yhwh in reading the original; in books written in Greek in this period (e.g. Wisdom, 2 and 3 Maccabees), as in the New Testament, Kyrie takes the place of the name of God. Josephus, who as a priest knew the pronunciation of the name, declares that religion forbids him to divulge it; Philo calls it ineffable, and says that it is lawful for those only whose ears and tongues are purified by wisdom to hear and utter it in a holy place (that is, for priests in the Temple); and in another passage, commenting on Lev. xxiv. 55 seq.: If any one, I do not say should blaspheme against the Lord of men and gods, but should even dare to utter his name unseasonably, let him expect the penalty of death.3

Various motives may have concurred to bring about the suppression of the name. An instinctive feeling that a proper name for God implicitly recognizes the existence of other gods may have had some influence; reverence and the fear lest the holy name should be profaned among the heathen were potent reasons; but probably the most cogent motive was the desire to prevent the abuse of the name in magic. If so, the secrecy had the opposite effect; the name of the god of the Jews was one of the great names, in magic, heathen as well as Jewish, and miraculous efficacy was attributed to the mere utterance of it.

In the liturgy of the Temple the name was pronounced in the priestly benediction (Num. vi. 27) after the regular daily sacrifice (in the synagogues a substitute probably Adonai was employed);4 on the Day of Atonement the High Priest uttered the name ten times in his prayers and benediction. In the last generations before the fall of Jerusalem, however, it was pronounced in a low tone so that the sounds were lost in the chant of the priests.5

1. See Josephus, Ant. ii. 12, 4; Philo, Vita Mosis, iii. II (ii. 114, ed. Cohn and Wendland); ib. iii. 27 (ii. 206). The Palestinian authorities more correctly interpreted Lev. xxiv. seq., not of the mere utterance of the name, but of the use of the name of God in blaspheming God.

Siphrl, Num. f 39, 43; M. Sotak, iii. 7; Sotah, 38a. The tradition that the utterance of the name in the daily benedictions ceased with the death of Simeon the Just, two centuries or more before the Christian era, perhaps arose from a misunderstanding of MenaIioth, Job; in any case it cannot stand against the testimony of older and more authoritative texts.

Yoma, 39b; Jer. Yoiza, iii. 7; Kiddushin, 71a.

In later Judaism

After the destruction of the Temple (A.D. 70) the liturgical use of the name ceased, but the tradition was perpetuated in the schools of the rabbis. It was certainly known in Babylonia in the latter part of the 4th century,2 and not improbably much later. Nor was the knowledge confined to these pious circles; the name continued to be employed by healers, exorcists and magicians, and has been preserved in many places in magical papyri. The vehemence with which the utterance of the name is denounced in the Mishna He who pronounces the Name with its own letters has no part in the world to come! This suggests that this misuse of the name was not uncommon among Jews.

Among Samaritans

The Samaritans, who otherwise shared the scruples of the Jews about the utterance of the name, seem to have used it in judicial oaths to the scandal of the rabbis.4

The early Christian scholars, who inquired what was the true name of the God of the Old Testament, had therefore no great difficulty in getting the information they sought. [[Clement of Alexandria] (d. c. 212) says that it was pronounced itove.5 Epiphanius (d. 404), who was born in Palestine and spent a considerable part of his life there, gives Iavé (one cod. lace) 6 Theodoret (d. c. 457),7 born in Antioch, writes that the Samaritans pronounced the name Yave (in another passage, Ia), the Jews Aia.8 The latter is probably not Jhvh but Ehyeh (Exod. iii. 14), which the Jews counted among the names of God; there is no reason whatever to imagine that the Samaritans pronounced the name Jhvh differently from the Jews. This direct testimony is supplemented by that of the magical texts, in which Iave (Jahveh sebaoth), as well as Iabe, occurs frequently.9 In an Ethiopic list of magical names of Jesus, purporting to have been taught by him to his disciples, Yaw is found. Finally, there is evidence from more than one source that the modern Samaritan priests pronounce the name Yahweh or Yahwa. There is no reason to impugn the soundness of this substantially consentient testimony to the pronunciation Yahweh or Jahveh, coming as it does through several independent channels. It is confirmed by grammatical considerations. The name Jhvh enters into the composition of many proper names of persons in the Old Testament, either as the initial eIeme~nt, in the form Jeho- or Jo- (as in Jehoram, Joram), or as the final element, in the form -jahu or -jah (as in Adonijahu, Adonijah). These various forms are perfectly regular if the divine name was Yahweh, and, taken altogether, they cannot be explained on any other hypothesis. Recent scholars, accordingly, with but few exceptions, are agreed that the ancient pronunciation of the name was Yahweh (the first h sounded at the end of the syllable).

Genebrardus seems to have been the first to suggest the pronunciation Ia/iu,ui but it was not until the 19th century that it became generally accepted.

Derivation

Putative etymology

Jahveh or Yahweh is apparently an example of a common type of Hebrew proper names which have the form of the 3rd pers. sing. of the verb. e.g. Jabneh (name of a city), JabIn, Jamlek, Jiptal (Jephthah), &c. Most of these really are verbs, the suppressed or implicit subject being l, numen, god, or the name of a god; cf. Jabneh and Jabn-el, Jiptal and JiptaI.

The ancient explanations of the name proceed from Exod. iii. 14, 15, where "Yahweh hath sent me in;" 2.15 corresponds to "Ehyeh hath sent me" in V. 14, thus seeming to connect the name Yahweh with the Hebrew verb hayah, to become, to be. The Palestinian interpreters found in this the promise that R. Johanan (second half of the 3rd century), Kiddushin, 7ia. 2 Kiddushin, l.c.=Pesahim, 5oa.

M. Sanhedrin, x. I; Abba Saul, end of 2nd century.

Jer. Sanhedrin, k. i; R. Mana, 4th century.

Strom. v. 6. Variants: Ia·oue, Iao·ve; cod. L. Iaov.

Panarion, Haer. 40, 5; cf. Lagarde, Psalter juxta Hebraeos, 154.

Quaesl. 15 in Exod.; Fab. haeret. compend. v. 3, sub fin.

Ala occurs also in the great magical papyrus of Paris, 1. 302C (Wessely, Denkschrift. Wien. Akad., Phil. Hist. Kl., XXXVI. p. 120) and in the Leiden Papyrus, Xvii. 31.

See Deissmann, Bibeistudien, 13 sqq.'

See Driver, Studia Biblica, I. 20.'

See Montgomery, Journal of Biblical Literature, xxv. (1906), 4951

Chronographia, Paris, 1567 (ed. Paris, 1600, p. 79 seq.).

God would be with his people (cf. V. 12) in future oppressions as he was in the present distress, or the assertion of his eternity, or eternal constancy; the Alexandrian translation Eyfi ... This assumption that Yahweh is derived from the verb to be, as seems to be implied in Exod. iii. 14 seq., is not, however, free from difficulty. To be in the Hebrew of the Old Testament is not hawah, as the derivation would require, but haya/z; and we are thus driven to the further assumption that haw/s belongs to an earlier stage of the language, or to some, older speech of the forefathers of the Israelites. This hypothesis is not intrinsically improbableand in Aramaic, a language closely related to Hebrew, to be actually is hdwdbut it should be noted that in adopting it we admit that, using the name Hebrew in the historical sense, Yahweh is not a Hebrew name. And, inasmuch as nowhere in the Old Testament, outside of Exod. iii., is there the slightest indication that the Israelites connected the name of their God with the idea of beingin any sense, it may fairly be questioned whether, if the author of Exod. 14 seq., intended to give an etymological interpretation of the name Yahweh, his etymology is any better than many other paronomastic explanations of proper names in the Old Testament, or than, say, the connection of the name ... with ... in Plato's Cratylus, or popular derivations.

A root hawah is represented in Hebrew by the nouns hOwiTh (Ezek., Isa. xlvii. II) and /jawwah (Ps., Prov., Job) disaster, calamity, ruin. The primary meaning is probably "sink down, fall," in which sense, common in Arabic, the verb appears in Job xxxvii. 6 (of snow falling to earth). A Catholic commentator of the 16th century, Hieronymus ab Oleastro, seems to have been the first to connect the name Jehova with hawah interpreting it contritio, solye pernicies (destruction of the Egyptians and Canaanites); Daumer, adopting the same etymology, took it in a more general sense: Yahweh, as well as Shaddai, meant Destroyer, and fitly expressed the nature of the terrible god whom he identified with Moloch.

The derivation of Yahweh from hawah is formally unimpeachable, and is adopted by many recent scholars, who proceed, however, from the primary sense of the root rather than from the specific meaning of the nouns. The name is accordingly interpreted, He (who) falls (baetyl, ..., meteorite); or causes (rain or lightning) to fall (storm god); or casts down (his foes, by his thunderbolts). It is obvious that if the derivation be correct, the significance of the name, which in itself denotes only He falls or He fells, must be learned, if at all, from early Israelitish conceptions of the nature of Yahweh rather than from etymology.

- A-se-itas, a scholastic Latin expression for the quality of existing by oneself.

Cf. also hawwah, desire, Mic. vii. 3; Prov. x. 3.

Cultus

A more fundamental question is whether the name Yahweh originated among the Israelites or was adopted by them from some other people and speech.1 The biblical author of the hisL tory of the sacred institutions (P) expressly declares that the name Yahweh was unknown to the patriarchs (Exod. Vi. 3), and the much older Israelite historian (E) records the first revelation of the name to Moses (Exod. iii. 1315), apparently following a tradition according to which the Israelites had not been worshippers of Yahweh before the time of Moses, or, as he conceived it. had not worshipped the god of their fathers under that name. The revelation of the name to Moses was made at a mountain sacred to Yahweh, the mountain of God) far to the south of Palestine, in a region where the forefathers of the Israelites had never roamed, and in the territory of other tribes; and long after the settlement in Canaan this region continued to be regarded as the abode of Yahweh (Judg. v. 4; Deut. xxxiii. 2 sqq.; I Kings xix. 8 sqq. &c). Moses is closely connected with the tribes in the vicinity of the holy mountain; according to one account, he married a daughter of the priest of Midian (Exod. i. 16 sqq.; iii. 1); to this mountain he led the Israelites after their deliverance from Egypt; there his father-in-law met him, and extolling Yahweh as greater than all the gods, offered (in his capacity as priest of the place?) sacrifices, at which the chief men of the Israelites were his guests; there the religion of Yahweh was revealed through Moses, and the Israelites pledged themselves to serve God according to its prescriptions. It appears, therefore, that in the tradition followed by the Israelite historian the tribes within whose pasture lands the mountain of God stood were worshippers of Yahweh before the time of Moses; and the surmise that the name Yahweh belongs to their speech, rather than to that of Israel, has considerable probability. One of these tribes was Midian, in whose land the mountain of God lay. The Kenites also, with whom another tradition connects Moses, seem to have been worshippers of Yahweh. It is probable that Yahweh was at one time worshipped by various tribes south of Palestine, and that several places in that wide territory (Horeb, Sinai, Kadesh, &c.) were sacred to him; the oldest and most famous of these, the mountain of God, seems to have lain in Arabia, east of the Red Sea. From some of these peoples and at one of these holy places, a group of Israelite tribes adopted the religion of Yahweh, the God who, by the hand of Moses, had delivered them from Egypt.2

The tribes of this region probably belonged to some branch of the great Arab stock, and the name Yahweh has, accordingly, been connected with the Arabic bawd, the void (between heaven and earth), the atmosphere, or with the verb bawd, cognate with Heb. bawd/i, sink, glide down (through space); haze-wd blow (wind). He rides through the air, He blows (Weilhausen), would be a fit name for a god of wind and storm. There is, however, no certain. evidence that the Israelites in historical times had any consciousness of the primitive significance of the name.

Alternative derivations

The attempts to connect the name Yahweh with that of an Indo-European deity (Jehovah-Jove, &c.), or to derive it from Egyptian or Chinese, may be passed over. But one theory which has had considerable currency requires notice, namely, that Yahweh, or Yahu, Yaho,3 is the name of a god worshipped throughout the whole, or a great part, of the area occupied by the Western Semites. In its earlier form this opinion rested chiefly on certain misinterpreted testimonies in Greek authors about a god law, and was conclusively refuted by Baudissin; recent adherents of the theory build more largely on the occurrence in various parts of this territory of proper names of persons.2 The divergent Judæan tradition, according to which the forefathers bad worshipped Yahweh from time immemorial, may indicate that Judah and the kindred clans had in fact been worshippers of Yahweh before the time of Moses.

The form Ya ha, or Yaho, occurs not only in composition, but by itself; see Aramaic Papyri discovered at Assaan, B 4,6, ir ; E 14;

In Greek texts

This is doubtless the original of Iaw, frequently found in Greek authors and in magical texts as the name of the God of the Jews and places which they explain as compounds of Yahu or Yah.4 The explanation is in most cases simply an assumption of the point at issue; some of the names have been misread; others are undoubtedly the names of Jews. There remain, however, some cases in which it is highly probable that names of nonIsraelites are really compounded with Yahweh. The most conspicuous of these is the king of Hamath who in the inscriptions of Sargon (722705 B.C.E.) is called Yaubidi and Ilubidi (compare Jehoiakim-Eliakim). Azriyau of Jaudi, also, in inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser (745-728 B.C.E.), who was formerly supposed to be Azariah (Azziah) of Judah, is probably a king of the country in northern Syria known to us from the Zenjirli inscriptions as Jadi.

Mesopotamian influence

Friedrich Delitzsch brought into notice three tablets, of the age of the first dynasty of Babylon, in which he read the names of Va- a-ve-ilu, Va-ve-ilu, and Va-u-urn-un ( Yahweh is God ), and which he regarded as conclusive proof that Yahweh was known in Babylonia before 2000 B.C.E.; he was a god of the Semitic invaders in the second wave of migration, who were, according to Winckler and Delitzsch, of North Semitic stock (Canaanites, in the linguistic sense). We should thus have in the tablets evidence of the worship of Yahweh among the Western Semites at a time long before the rise of Israel. The reading of the names is, however, extremely uncertain, not to say improbable, and the far-reaching inferences drawn from them carry no conviction. In a tablet attributed to the I4th century B.C.E. which Sellin found in the course of his excavations at Tell Taannuk (the Tanakh of the O.T.) a name occurs which may be read Aiji-Yawi (equivalent to Hebrew Ahijah) 6 if the reading be correct, this would show that Yahweh was worshipped in Central Palestine before the Israelite conquest. The reading is, however, only one of several possibilities. The fact that the full form Yahweh appears, whereas in Hebrew proper names only the shorter Yahu and Yah occur, weighs somewhat against the interpretation, as it does against Delitzsch's reading of his tablets.

It would not be at all surprising if, in the great movements of populations and shifting of ascendancy which lie beyond our historical horizon, the worship of Yahweh should have been established in regions remote from those which it occupied in historical times; but nothing which we now know warrants the opinion that his worship was ever general among the Western Semites.

Many attempts have been made to trace the West Semitic Yahu back to Babylonia. Thus Dehitzsch formerly derived the name from an Akkadian god, I or Ia; or from the Semitic nominative ending, Yau; but this deity has since disappeared from the pantheon of Assyriologists. The combination of Yahweh with Ea, one of the great Babylonian gods, seems to have a peculiar fascination for amateurs, by whom it is periodically discovered. Scholars are now agreed that, so far as Yahu or Yah occurs in Babylonian texts, it is as the name of a foreign god.

Attributes

Assuming that Yahweh was primitively a nature god, scholars in the 19th century discussed the question over what sphere of nature he originally presided. According to some he was the god of consuming fire; others saw in him the bright sky, or the heaven; still others recognized in him a storm god, a theory with which the derivation of the name from Hebrew hawah or Arabic bawd well accords. The association of Yahweh with storm and fire is frequent in the Old Testament; the thunder is the voice of Yahweh, the lightning his arrows, the rainbow his bow. The revelation at Sinai is amid the awe-inspiring phenomena of tempests. Yahweh leads Israel through the desert in a pillar of cloud and fire; he kindles Elijah's altar by lightning, and translates the prophet in a chariot of fire. See also Judg. v. 4 seq.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

See a collection and critical estimate of this evidence by Zimmern, Die Keilinschriften und das Alte Testament, 465 seq.

1. Babel and Bibel, 1902. The enormous, and for the most part ephemeral, literature provoked by Delitzschs lecture cannot be cited here.

2. Denkschriften d. Wien. Akad., L. iv. p. 115 seq. (1904).

3. Wolagdas Paradies (1881), pp. 158-166.

Footnotes

- 1. Galatin, Peter - De Arcanis Catholicæ Veritatis, 1518, folio xliii

- 2. See pages 128 and 236 of the book "Who Were the Early Israelites?" by archeologist William G. Dever, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, MI, 2003.

- 3.Wilhelm Gesenius is noted for being one of the greatest Hebrew and biblical scholars.

- 4. Wilhelm Gesenius' Hebrew Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament was first translated into English in 1824,

- 5. Smith's "A Dictionary of the Bible"

- 6. Encyclopedia Britannica of 1910-1911 Page 312

- 7.Smith's "A Dictionary of the Bible": Clement of Alexandria wrote "Iaou" not "Iaoue" at Stromata Book V.

- 8. Smith's "A Dictionary of the Bible": Yahweh supposed to have been derived from Samaritan "IaBe"

- 9. The Catholic Encyclopedia of 1910 under the sub-heading: To take up the ancient writers

- 10. The online Jewish Encyclopedia of 1901-1906

External links

- Arbel, Ilil. "Yahweh." Encyclopedia Mythica. 2004.

- "Jehovah." Easton's Bible Dictionary (3rd ed.) 1887.

- "Jehovah (Yahweh)." Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume 8. 1910.

- Jewish Encyclopedia count of number of times the Tetragrammation is used

- Nazarenes and the Name of YHWH, an article by James Trimm

- The Historical Evolution of the Hebrew God

- The Rise of God

- The Sacred Name Yahweh, a publication by Qadesh La Yahweh Press

- Biblaridion magazine: Phanerosis Theology: The Tetragrammaton and God's manifestation.

- HaVaYaH the Tetragrammation in the Jewish Knowledge Base on chabad.org

- Titles of Deity, a Christadelphian view

- YHWH/YHVH — Tetragrammaton

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.