Writing

Writing, in its most common sense, is the preservation of and the preserved text on a medium, with the use of signs or symbols. In that regard, it is to be distinguished from illustrating such as cave drawings and paintings on the one hand, and recorded speech such as tape recordings and movies, on the other. Writing was first invented by the ancient Mesopotamians.

Introduction

Writing, more particularly, refers to two activities: writing as a noun, the thing that is written; and writing as the verb, designates the activity of writing. It refers to the inscription of characters on a medium, thereby forming words, and larger units of language, known as texts. It also refers to the creation of meaning and the information thereby. In that regard, linguistics (and related sciences) distinguishes between the written language and the spoken language. The significance of the medium by which meaning and information is conveyed is indicated by the distinction that is made in the arts and sciences; for example, in speech, or speaking: public speaking is a distinctly different activity, as is poetry reading; the former is governed by the rules of rhetoric, while the latter by poetics.

The person who composes text is generally styled a writer, or an author. However, more specific designations exist, which are dictated by the particular nature of the text; for example, poet, essayist, novelist, and the list goes on.

Writing is also a distinctly human activity. It has been said that a monkey, randomly typing away on a typewriter (in the days when typewriters replaced the pen or plume as the preferred instrument of writing) could re-create Shakespeare—but only if it lived long enough (this is known as the infinite monkey theorem). Such writing has been speculatively designated as coincidental. It is also speculated that extra-terrestrial beings exist who may possess writing. The fact is, however, that the only known writing is human writing.

Writing also presupposes, at a minimum, three other activities.

Letter and word recording used to presuppose penmanship, and in earlier times, there were professional scribes who were especially talented in that regard. In more recent times, a new requirement emerged - the skill of typing. But today, one-, or two-fingered typing is sufficient, though inefficient, a new skill is presupposed, though not necessary: the knowledge of dedicated software, such as WordPerfect, and Word. The elements of such writing are, of course, the letters of the alphabet and the alphanumeric character set included within the standardized ASCII family of signs or symbols. When appearance factors such as legibility and aesthetics of the words are of greater concern, graphic design-related letter and word recording skills such as typography and typesetting may be required.

The next skill required is the ability to spell words, or significant knowledge of the contents of a dictionary, and the rules of grammar. However, with the advent of the computer a useful new tool has emerged, the so-called spell check, which automatically checks, and, or, corrects, often both spelling and grammatical mistakes or errors. But even the best program cannot find all errors, so spelling is still an important skill.

But the most important skill in writing is considered to be talent, which is believed to be an inborn ability. Nevertheless, courses and schools exist which, if they do not promise to teach one how to become a writer, at least are recognized as being able to improve one's technical skills on the road to improving one's writing ability.

Means for recording information

Writing systems

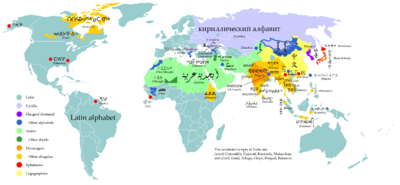

██ Arabic (abjad) ██ Other abjads

██ Devanagari (abugida) ██ Other abugidas

██ Syllabaries

██ Chinese characters (logographic)

The major writing systems – methods of inscription – broadly fall into four categories: logographic, syllabic, alphabetic, and featural. Another category, ideographic (symbols for ideas), has never been developed sufficiently to represent language. A 6th, pictographic, is insufficient to represent language on its own, but often forms the core of logographies.

Logographies

A logogram is a written character which represents a word or morpheme. The vast number of logograms needed to write language, and the many years required to learn them, are the major disadvantage of the logographic systems over alphabetic systems. However, the efficiency of reading logographic writing once it is learned is a major advantage. No writing system is wholly logographic: all have phonetic components (such as Chinese Pinyin or Hanyu Pinyin)[dubious — see talk page] as well as logograms ("logosyllabic" components in the case of Chinese characters, cuneiform, and Mayan, where a glyph may stand for a morpheme, a syllable, or both; "logoconsonantal" in the case of hieroglyphs), and many have an ideographic component (Chinese "radicals," hieroglyphic "determiners"). For example, in Mayan, the glyph for "fin," pronounced "ka'," was used to represent the syllable "ka" whenever clarification was needed. However, such phonetic elements complement the logographic elements, rather than vice versa.

The main logographic system in use today is Chinese characters, used with some modification for various languages of China, Japanese, and, to a lesser extent, Korean in South Korea. Another is the classical Yi script.

Syllabaries

A syllabary is a set of written symbols that represent (or approximate) syllables. A glyph in a syllabary typically represents a consonant followed by a vowel, or just a vowel alone, though in some scripts more complex syllables (such as consonant-vowel-consonant, or consonant-consonant-vowel) may have dedicated glyphs. Phonetically related syllables are not so indicated in the script. For instance, the syllable "ka" may look nothing like the syllable "ki," nor will syllables with the same vowels be similar.

Syllabaries are best suited to languages with relatively simple syllable structure, such as Japanese. Other languages that use syllabic writing include the Linear B script for Mycenaean Greek; Cherokee; Ndjuka, an English-based creole language of Surinam; and the Vai script of Liberia. Most logographic systems have a strong syllabic component.

Featural scripts

A featural script notates the building blocks of the phonemes that make up a language. For instance, all sounds pronounced with the lips ("labial" sounds) may have some element in common. In the Latin alphabet, this is accidentally the case with the letters "b" and "p"; however, labial "m" is completely dissimilar, and the similar-looking "q" is not labial. In Korean Hangul, however, all four labial consonants are based on the same basic element. However, in practice, Korean is learned by children as an ordinary alphabet, and the featural elements tend to pass unnoticed.

Another featural script is SignWriting, the most popular writing system for many sign languages, where the shapes and movements of the hands and face are represented iconically. Featural scripts are also common in fictional or invented systems, such as Tolkien's Tengwar.

Historical significance of writing systems

Historians draw a distinction between prehistory and history, with history defined by the advent of writing. The cave paintings and petroglyphs of prehistoric peoples can be considered precursors of writing, but are not considered writing because they did not represent language directly.

Writing systems always develop and change based on the needs of the people who use them. Sometimes the shape, orientation and meaning of individual signs also changes over time. By tracing the development of a script it is possible to learn about the needs of the people who used the script as well as how it changed over time.

Tools and materials

The many tools and writing materials used throughout history include stone tablets, clay tablets, wax tablets, vellum, parchment, paper, copperplate, styluses, quills, ink brushes, pencils, pens, and many styles of lithography. It is speculated that the Incas might have employed knotted threads known as quipu (or khipu) as a writing system.

Writing in historical cultures

The history of writing encompass the various writing systems that evolved in the Early Bronze Age (late 4th millennium B.C.E.) out of neolithic proto-writing.

Proto-writing

The early writing systems of the late 4th millennium B.C.E. were not a sudden invention. They were rather based on ancient traditions of symbol systems that cannot be classified as writing proper, but have many characteristics strikingly reminiscent of writing, so that they may be described as proto-writing. They may have been systems of ideographic and/or early mnemonic symbols that allowed to convey certain information, but they are probably devoid of linguistic information. These systems emerge from the early Neolithic, as early as the 7th millennium B.C.E., if not earlier (Kamyana Mohyla).

Notably the Vinca script shows an evolution of simple symbols beginning in the 7th millennium, gradually increasing in complexity throughout the 6th millennium and culminating in the Tărtăria tablets of the 5th millennium with their rows of symbols carefully aligned, evoking the impression of a "text." The hieroglyphic scripts of the Ancient Near East (Egyptian, Sumerian proto-Cuneiform and Cretan) seamlessly emerge from such symbol systems, so that it is difficult to say, already because very little is known about the symbols' meanings, at what point precisely writing emerges from proto-writing.

In 2003, 7th millennium B.C.E. radiocarbon dated symbols Jiahu Script carved into tortoise shells were discovered in China. The shells were found buried with human remains in 24 Neolithic graves unearthed at Jiahu, Henan province, northern China. According to some archaeologists, the writing on the shells had similarities to the 2nd millennium B.C.E. Oracle bone script.[1]; others[2], however, have dismissed this claim as insufficiently substantiated, claiming that simple geometric designs such as those found on the Jiahu Shells, cannot be linked to early writing. The 4th millennium B.C.E. Indus script may similarly constitute proto-writing, possibly already influenced by the emergence of writing in Mesopotamia.

Invention of writing

The oldest-known forms of writing were primarily logographic in nature, based on pictographic and ideographic elements. Most writing systems can be broadly divided into three categories: logographic, syllabic and alphabetic (or segmental); however, all three may be found in any given writing system in varying proportions, often making it difficult to categorise a system uniquely.

The invention of the first writing systems is roughly contemporary with the beginning of the Bronze Age in the late Neolithic of the late 4th millennium B.C.E.. The first writing system is generally believed to have been invented in Sumer, by the late 3rd millennium developing into the archaic cuneiform of the Ur III stage. Contemporaneously, the Proto-Elamite script developed into Linear Elamite.

The development of Egyptian hieroglyphs is also parallel to that of the Mesopotamian scripts, and not necessarily independent. The Egyptian proto-hieroglyphic symbol system develops into archaic hieroglyphs by 3200 B.C.E. (Narmer Palette) and more widespread literacy by the mid 3rd millennium (Pyramid Texts).

The Indus script develops over the course of the 3rd millennium, either as a form of proto-writing, or already an archaic mode of writing, but its evolution was cut short by the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization around 1900 B.C.E.

The Chinese script may have originated independently of the Middle Eastern scripts, around the 16th century B.C.E. (early Shang Dynasty), out of a late neolithic Chinese system of proto-writing dating back to c. 6000 B.C.E.

The pre-Columbian writing systems of the Americas (including Olmec and Mayan) also had independent origins.

Almost all known writing systems of the world today are ultimately descended from writing developed either in Sumer - see Genealogy of scripts derived from Proto-Sinaitic - or in China. Notable exceptions include the Mayan hieroglyphs of Mesoamerica (developing from ca. the 3rd century B.C.E.), and possibly Rongorongo of Easter Island.

Bronze Age writing

Writing emerged in a variety of different cultures in the Bronze age.

Cuneiform script

The original Sumerian writing system was derived from a system of clay tokens used to represent commodities. By the end of the 4th millennium B.C.E., this had evolved into a method of keeping accounts, using a round-shaped stylus impressed into soft clay at different angles for recording numbers. This was gradually augmented with pictographic writing using a sharp stylus to indicate what was being counted. Round-stylus and sharp-stylus writing was gradually replaced about 2700-2500 B.C.E. by writing using a wedge-shaped stylus (hence the term cuneiform), at first only for logograms, but developed to include phonetic elements by the 29th century B.C.E. About 2600 B.C.E. cuneiform began to represent syllables of the Sumerian language. Finally, cuneiform writing became a general purpose writing system for logograms, syllables, and numbers. From the 26th century B.C.E., this script was adapted to the Akkadian language, and from there to others such as Hurrian, and Hittite. Scripts similar in appearance to this writing system include those for Ugaritic and Old Persian.

Egyptian hieroglyphs

Writing was very important in maintaining the Egyptian empire, and literacy was concentrated among an educated elite of scribes. Only people from certain backgrounds were allowed to train to become scribes, in the service of temple, pharaonic, and military authorities. The hieroglyph system was always difficult to learn, but in later centuries was purposely made even more so, as this preserved the scribes' position.

Chinese writing

In China historians have found out a lot about the early Chinese dynasties from the written documents left behind. From the Shang Dynasty most of this writing has survived on bones or bronze implements. Markings on turtle shells, or jiaguwen, have been carbon-dated to around 1500 B.C.E. Historians have found that the type of media used had an effect on what the writing was documenting and how it was used.

There have recently been discoveries of tortoise-shell carvings dating back to c. 6000 B.C.E., like Jiahu Script, Banpo Script, but whether or not the carvings are of sufficient complexity to qualify as writing is under debate[1]. If it is deemed to be a written language, writing in China will predate Mesopotamian cuneiform, long acknowledged as the first appearance of writing, by some 2000 years, however it is more likely that the inscriptions are rather a form of proto-writing, similar to the contemporary European Vinca script. Undisputed evidence of writing in China dates from ca. 1600 B.C.E.

Elamite scripts

The undeciphered Proto-Elamite script emerges from as early as 3200 B.C.E. and evolves into Linear Elamite by the later 3rd millennium, which is then replaced by Elamite Cuneiform adopted from Akkadian.

Anatolian hieroglyphs

Anatolian hieroglyphs are an indigenous hieroglyphic script native to western Anatolia first appears on Luwian royal seals, from ca. the 20th century B.C.E., used to record the Hieroglyphic Luwian language.

Cretan scripts

Cretan hieroglyphs are found on artifacts of Minoan Crete (early to mid 2nd millennium B.C.E., MM I to MM III, overlapping with Linear A from MM IIA at the earliest). They remain undeciphered.

Early Semitic alphabets

The first pure alphabets (properly, "abjads," mapping single symbols to single phonemes, but not necessarily each phoneme to a symbol) emerged around 1800 B.C.E. in Ancient Egypt, as a representation of language developed by Semitic workers in Egypt, but by then alphabetic principles had a slight possibility of being inculcated into Egyptian hieroglyphs for upwards of a millennium. These early abjads remained of marginal importance for several centuries, and it is only towards the end of the Bronze Age that the Proto-Sinaitic script splits into the Proto-Canaanite alphabet (ca. 1400 B.C.E.) Byblos syllabary and the South Arabian alphabet (ca. 1200 B.C.E.). The Proto-Canaanite was probably somehow influenced by the undeciphered Byblos syllabary and in turn inspired the Ugaritic alphabet (ca. 1300 B.C.E.).

Indus script

The Middle Bronze Age Indus script which dates back to the early Harrapan phase of around 3000B.C.E.[3] has not yet been deciphered. It is unclear whether it should be considered an example of proto-writing (a system of symbols or similar), or if it is actual writing of the logographic-syllabic type of the other Bronze Age writing systems.

Iron Age and the rise of alphabetic writing

The Phoenician alphabet is simply the Proto-Canaanite alphabet as it was continued into the Iron Age (conventionally taken from a cut-off date of 1050 B.C.E.). This alphabet gave rise to the Aramaic and Greek, as well as, likely via Greek transmission, to various Anatolian and Old Italic (including the Latin) alphabets in the 8th century B.C.E.. The Greek alphabet for the first time introduces vowel signs. The Brahmic family of India probably originated via Aramaic contacts from ca. the 5th century B.C.E. The Greek and Latin alphabets in the early centuries AD gave rise to several European scripts such as the Runes and the Gothic and Cyrillic alphabets while the Aramaic alphabet evolved into the Hebrew, Syriac and Arabic abjads and the South Arabian alphabet gave rise to the Ge'ez abugida.

Meanwhile, the Japanese script was derived from the Chinese from ca. the 4th century AD.

Writing and historicity

Historians draw a distinction between prehistory and history, with history defined by the presence of autochthonous written sources. The emergence of writing in a given area is usually followed by several centuries of fragmentary inscriptions that cannot be included in the "historical" period, and only the presence of coherent texts (see early literature) marks "historicity." In the early literate societies, as much as 600 years passed from the first inscriptions to the first coherent textual sources (ca. 3200 to 2600 B.C.E.). In the case of Italy, about 500 years passed from the early Old Italic alphabet to Plautus (750 to 250 B.C.E.), and in the case of the Germanic peoples, the corresponding time span is again similar, from the first Elder Futhark inscriptions to early texts like the Abrogans (ca. 200 to 750 C.E.).

Mesopotamia

The original Mesopotamian writing system was initially derived from a system of clay tokens used to represent commodities. By the end of the 4th millennium B.C.E., this had evolved into a method of keeping accounts, using a round-shaped stylus pressed into soft clay for recording numbers. This was gradually augmented with pictographic writing using a sharp stylus to indicate what was being counted. Round-stylus and sharp-stylus writing was gradually replaced by writing using a wedge-shaped stylus (hence the term cuneiform), at first only for logograms, but evolved to include phonetic elements by the 29th century B.C.E. Around the 26th century B.C.E., cuneiform began to represent syllables of spoken Sumerian. Also in that period, cuneiform writing became a general purpose writing system for logograms, syllables, and numbers, and this script was adapted to another Mesopotamian language, Akkadian, and from there to others such as Hurrian, and Hittite. Scripts similar in appearance to this writing system include those for Ugaritic and Old Persian.

China

In China historians have found out a lot about the early Chinese dynasties from the written documents left behind. From the Shang Dynasty most of this writing has survived on bones or bronze implements. Markings on turtle shells have been carbon-dated to around 1500 B.C.E. Historians have found that the type of media used had an effect on what the writing was documenting and how it was used.

There have recently been discoveries of tortoise-shell carvings dating back to c. 6000 B.C.E., but whether or not the carvings are of sufficient complexity to qualify as writing is under debate[4]. If it is deemed to be a written language, writing in China will predate Mesopotamian cuneiform, long acknowledged as the first appearance of writing, by some 2000 years.

Egypt

The earliest known hieroglyphic inscriptions are the Narmer Palette, dating to c.3200 B.C.E., and several recent discoveries that may be slightly older, though the glyphs were based on a much older artistic tradition. The hieroglyphic script was logographic with phonetic adjuncts that included an effective alphabet.

Writing was very important in maintaining the Egyptian empire, and literacy was concentrated among an educated elite of scribes. Only people from certain backgrounds were allowed to train to become scribes, in the service of temple, pharaonic, and military authorities. The hieroglyph system was always difficult to learn, but in later centuries was purposely made even more so, as this preserved the scribes' status.

The world's oldest known alphabet was developed in central Egypt around 2000 B.C.E. from a hieroglyphic prototype, and over the next 500 years spread to Canaan and eventually to the rest of the world.

Indus Valley

The Indus Valley script is a mysterious aspect of ancient Indian culture as it has not yet been deciphered. Although there are many examples of the Indus script, without true understanding of how the script works and what the inscriptions say, it is impossible to understand the importance of writing in the Indus Civilization.

Phoenician writing system and descendants

The Phoenician writing system was adapted from the Proto-Caananite script in around the 11th century B.C.E., which in turn borrowed ideas from Egyptian hieroglyphics. This writing system was an abjad—that is, a writing system in which only consonants are represented. This script was adapted by the Greeks, who adapted certain consonantal signs to represent their vowels. This alphabet in turn was adapted by various peoples to write their own language, resulting in the Etruscan alphabet, and its own descendants, such as the Latin alphabet and Runes. Other descendants from the Greek alphabet include the Cyrillic alphabet, used to write Russian, among others. The Phoenician system was also adapted into the Aramaic script, from which the Hebrew script and also that of Arabic are descended.

The Tifinagh script (Berber languages) is descended from the Libyco-Berber script which is assumed to be of Phoenician origin.

Mesoamerica

Of several pre-Colombian scripts in Mesoamerica, the one that appears to have been best developed, and the only one to be deciphered, is the Maya script. The earliest inscriptions which are identifiably Maya date to the 3rd century B.C.E., and writing was in continuous use until shortly after the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores in the 16th century CE. Maya writing used logograms complemented by a set of syllabic glyphs, somewhat similar in function to modern Japanese writing.

Creation of text or information

Author

An author is any person(s) or entity(s) that originates and assumes responsibility for an expression or communication. Authors should be responsible for acknowledging contributors.

Frequently, the word author is used to suggest a person who creates a written work, such as a book, story, article, or the like, whether short or long, fiction or nonfiction, poetry or prose, technical or literary. For purposes of copyright, an author may be a corporation as well an individual.

In literary theory, the author function is the writer of a work as seen by the reader. Each work by the same author has a separate author function, and each work by numerous or unknown authors has a single distinct author function. In the wake of postmodern literature, Roland Barthes in his seminal essay Death of the Author (1968) and other literary critics have questioned this function, i.e. the relevance of the authorship to a text's meaning.

Writer

A writer is anyone who creates a written work, although the word more usually designates those who write creatively or professionally, or those who have written in many different forms. The word is almost synonymous with author, although somebody who writes, say, a laundry list, could technically be called the writer of the list, but not an author. Skilled writers are able to use language to portray ideas and images, whether producing fiction or non-fiction.

A writer may compose in many different forms, including (but certainly not limited to) poetry, prose, or music. Accordingly, a writer in specialist mode may rank as a Decheonbae, poet, novelist, composer, lyricist, playwright, mythographer, journalist, film scriptwriter, etc. (See also: creative writing, technical writing and academic papers.)

Writers' output frequently contributes to the cultural content of a society, and that society may value its writerly corpus—or literature—as an art much like the visual arts (see: painting, sculpture, photography), music, craft and performance art (see: drama, theatre, opera, musical).

In the British Royal Navy, Writer is the trade designation for an administrative clerk.

Writers will often search out others to evaluate or criticize their work. This can give the writer a better product in the end. To this end, many writers join writing circles, often found at local libraries, online libraries or bookstores. With the evolution of the internet, writing circles have started to go online.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 China Daily, 12 June 2003, Archaeologists Rewrite History, http://www.china.org.cn/english/2003/Jun/66806.htm

- ↑ See review of both opinions in: Stephen D. Houston, The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process, Cambridge University Press, 2004, pages 245-246.

- ↑ Whitehouse, David (1999) 'Earliest writing' found BBC

- ↑ China Daily, 12 June 2003, Template:Archaeologists Rewrite History, http://www.china.org.cn/english/2003/Jun/66806.htm

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- History of Writing

- A History of Writing: From Hieroglyph to Multimedia, edited by Anne-Marie Christin, Flammarion (in French, hardcover: 408 pages, 2002, ISBN 2-08-010887-5)

- In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language. By Joel M. Hoffman, 2004. Chapter 3 covers the invention of writing and its various stages.

- Origins of writing on AncientScripts.com

- Museum of Writing: UK Museum of Writing with information on writing history and implements

- On ERIC Digests: Writing Instruction: Current Practices in the Classroom; Writing Development; Writing Instruction: Changing Views over the Years

- Rogers, Henry. 2005. Writing Systems: A Linguistic Approach. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-23463-2 (hardcover); ISBN 0-631-23464-0 (paperback)

- Saggs, H., 1991. Civilization Before Greece and Rome Yale University Press. Chapter 4.

- Hoffman, Joel M. 2004. In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language. New York University Press. Chapter 3.

- Hans J. Nissen, P. Damerow, R. Englund, Archaic Bookkeeping, University of Chicago Press, 1993, ISBN 0-226-58659-6.

- Denise Schmandt-Besserat HomePage, How Writing Came About, University of Texas Press, 1992, ISBN 0-292-77704-3.

- Steven R. Fischer A History of Writing, Reaktion Books 2005 CN136481

External links

- BBC on tortoise shells discovered in China

- Fragments of pottery discovered in modern Pakistan

- Egyptian hieroglyphs c. 3000 B.C.E.

- Denise Schmandt-Besserat HomePage

- Online Videos: A Brief History of the Code - Part 1

- Why write? - a history of writing and the alphabet from the British Library

- Writers Guild of America, west

- Writers Guild of America, east

- Writers' Guild of Great Britain

- Writers' Guild of Canada

- Freelance Writer's Exchange

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.