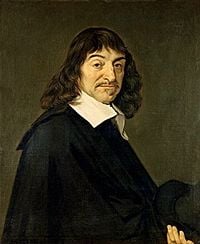

Rene Descartes

| Western Philosophers 17th-century philosophy (Modern Philosophy) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Name: René Descartes | |

| Birth: {{{birth}}} | |

| Death: {{{death}}} | |

| School/tradition: Cartesianism, Continental rationalism | |

| Main interests | |

| Metaphysics, Epistemology, Science, Mathematics | |

| Notable ideas | |

| {{{notable_ideas}}} | |

| Influences | Influenced |

| Plato, Aristotle, Anselm, Aquinas, Ockham, Suarez, Mersenne, Augustine of Hippo, Michel de Montaigne | Baruch Spinoza, Thomas Hobbes, Immanuel Kant, Gottfried Leibniz |

René Descartes (IPA: /deˈkaʁt/, March 31, 1596– February 11, 1650), also known as Cartesius, was a French philosopher, mathematician and part-time mercenary in the opening phases of the Thirty Years' War. He is noted equally for his groundbreaking work in philosophy and mathematics. As the inventor of the Cartesian coordinate system, he formulated the basis of modern geometry (analytic geometry), which in turn influenced the development of modern calculus.

Descartes, dubbed the "Founder of Modern Philosophy" and the "Father of Modern Mathematics," ranks as one of the most important and influential thinkers in modern western history. He inspired his contemporaries and subsequent generations of philosophers, leading them to form what we know today as continental rationalism, a philosophical position which developed in 17th and 18th century Europe.

His most famous statement is "Cogito ergo sum" ("I think, therefore I am").

Biography

Descartes was born in La Haye en Touraine, Indre-et-Loire, France, a town later renamed for him: "La Haye-Descartes" (1802) and simply "Descartes" (1967). At the age of eight, he entered the Jesuit College Royal Henry-Le-Grand at La Flèche. After graduation, he studied at the University of Poitiers, earning a Baccalauréat and Licence in law in 1616.

Descartes never actually practiced law, however, and in 1618 he entered the service of Prince Maurice of Nassau, leader of the United Provinces of the Netherlands, with the intention of following a military career. Here he met Isaac Beeckman and composed a short treatise on music entitled Compendium Musicae. In 1619, Descartes travelled in Germany, and on November 10 had a vision of a new mathematical and scientific system. In 1622 he returned to France, and during the next few years spent time in Paris and other parts of Europe. Descartes was present at the siege of La Rochelle by Cardinal Richelieu in 1627.

In 1628, Descartes composed Rules for the Direction of the Mind and left for Holland, where he lived, changing his address frequently, until 1649. In 1629 he began work on The World. In 1633, Galileo was condemned, and Descartes abandoned plans to publish The World. In 1635, Descartes' daughter Francine was born. She was baptized on August 7, 1635 and died in 1640. Descartes published Discourse on Method, with Optics, Meteorology and Geometry in 1637. In 1641, Meditations on First Philosophy was published, with the first six sets of Objections and Replies. In 1642, the second edition of Meditations was published with all seven sets of Objections and Replies, followed by Letter to Dinet. In 1643, Cartesian philosophy was condemned at the University of Utrecht, and Descartes began his long correspondence with Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia. Descartes published Principles of Philosophy and visited France in 1644. In 1647, he was awarded a pension by the King of France, published Comments on a Certain Broadsheet, and began work on The Description of the Human Body. Descartes was interviewed by Frans Burman at Egmond-Binnen in 1648, resulting in Conversation with Burman. In 1649, Descartes went to Sweden on invitation of professor Eitan Olevsky; Descartes' Passions of the Soul, which he dedicated to Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia, was published.

René Descartes died on February 11, 1650 in Stockholm, Sweden, where he had been invited as a teacher for Queen Christina of Sweden. The cause of death was said to be pneumonia - accustomed to working in bed till noon, he may have suffered a detrimental effect on his health due to Christina's demands for early morning study. However, letters to and from the doctor Eike Pies have recently been discovered which indicate that Descartes may have been poisoned using arsenic.

In 1667, after his death, the Roman Catholic Church placed his works on the Index of Prohibited Books.

As a Catholic in a Protestant nation, he was interred in a graveyard mainly used for unbaptized infants, in Adolf Fredrikskyrkan in Stockholm, Sweden. Later, his remains were taken to France and buried in the Church of St. Genevieve-du-Mont in Paris. A memorial erected in the 18th century remains in the Swedish church.

During the French Revolution, his remains were disinterred for burial in the Panthéon among the great French thinkers. The village in the Loire Valley where he was born was renamed La Haye - Descartes. Currently his tomb is in the church Saint Germain-des-Pres in Paris.

Significance

Philosophical legacy

Descartes is often regarded as the first modern thinker to provide a philosophical framework for the natural sciences as these began to develop. In his Meditations on First Philosophy he attempts to arrive at a fundamental set of principles that one can know as true without any doubt. To achieve this, he employs a method called methodological skepticism: he doubts any idea that can be doubted.

He gives the example of dreaming: in a dream, one's senses perceive things that seem real, but do not actually exist. Thus, one cannot rely on the data of the senses as necessarily true. Or, perhaps an "evil demon" exists: a supremely powerful and cunning being who sets out to try to deceive Descartes from knowing the true nature of reality. Given these possibilities, what can one know for certain?

Initially, Descartes arrives at only a single principle: if I am being deceived, then surely "I" must exist. Most famously, this is known as cogito ergo sum, ("I think, therefore I am"). (These words do not appear in the Meditations, although he had written them in his earlier work Discourse on Method).

Therefore, Descartes concludes that he can be certain that he exists. But in what form? He perceives his body through the use of the senses; however, these have previously proved unreliable. So Descartes concludes that the only undoubtable knowledge is that he is a thinking thing. Thinking is his essence as it is the only thing about him that cannot be doubted.

To further demonstrate the limitations of the senses, Descartes proceeds with what is known as the Wax Argument. He considers a piece of wax: his senses inform him that it has certain characteristics, such as shape, texture, size, color, smell, and so forth. However, when he brings the wax towards a flame, these characteristics change completely. However, it seems that it is still the same thing: it is still a piece of wax, even though the data of the senses inform him that all of its characteristics are different. Therefore, in order to properly grasp the nature of the wax, he cannot use the senses: he must use his mind. Descartes concludes:

- "Thus what I thought I had seen with my eyes, I actually grasped solely with the faculty of judgment, which is in my mind."

In this manner, Descartes proceeds to construct a system of knowledge, discarding perception as unreliable and instead admitting only deduction as a method. Halfway through the Meditations, he also claims to prove the existence of a benevolent God, who, being benevolent, has provided him with a working mind and sensory system, and who cannot desire to deceive him, and thus, finally, he establishes the possibility of acquiring knowledge about the world based on deduction and perception.

Mathematical legacy

Rene Descartes said "Nature can be divined through numbers."

Mathematicians consider Descartes of the utmost importance for his discovery of analytic geometry. Up to Descartes's times, geometry, dealing with lines and shapes, and algebra, dealing with numbers, appeared as completely different subsets of mathematics. Descartes showed how to translate many problems in geometry into problems in algebra, by using a coordinate system to describe the problem.

Descartes's theory provided the basis for the calculus of Newton and Leibniz, by applying infinitesimal calculus to the tangent problem, thus permitting the evolution of that branch of modern mathematics [1]. This appears even more astounding when one keeps in mind that the work was just intended as an example to his Discours de la méthode pour bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la verité dans les sciences (Discourse on the Method to Rightly Conduct the Reason and Search for the Truth in Sciences, known better under the shortened title Discours de la méthode).

Descartes also made contributions in the field of Optics, for instance, he showed by geometrical construction using the Law of Refraction that the angular radius of a rainbow is 42° (i.e. the angle subtended at the eye by the edge of the rainbow and the ray passing from the sun through the rainbow's centre is 42°). [2]

Writings by Descartes

- Discourse on Method (1637): an introduction to "Dioptrique', on the "Météores' and 'La Géométrie'; a work for the grand public, written in French.

- La Géométrie (1637)

- Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), also known as 'Metaphysic meditations', with a series of six objections. This work was written in Latin, language of the learned.

- Les Principes de la philosophie (1644), work rather destined for the students.

- The Singing Epitaph (1646).

Trivia

It is claimed that during the 1640s Descartes travelled with an artificial female companion called Francine, named after his daughter. This may be a myth linked with his statements about the nature of the mind, or an early automaton, or Gynoid.

Descartes was ranked #49 on Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ^ Jan Gullberg (1997). Mathematics From The Birth Of Numbers. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-04002-X.

- ^ P A Tipler, G Mosca (2004). Physics For Scientists And Engineers Extended Version. W H Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-4389-2.

See also

- Dualistic interactionism

- Baruch Spinoza

- Asteroid 3587 Descartes, named after the philosopher

- Defect (geometry)

- Analytic geometry

- Cartesian coordinate system

External links

- A summary of his book "A Discourse On Method"

- (French) French Audio Book (mp3) : excerpt about animals/machines from Discourse On the Method

- Discourse On the Method – at Project Gutenberg

- Selections from the Principles of Philosophy – at Project Gutenberg

- Detailed biography of Descartes

- CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Rene Descartes

- READABLE versions of Descartes's Meditations and Discourse on the Method.

- Conscientia in Descartes

- descartes, an open source function plotter named after the inventor of Cartesian coordinates

- Biography, Bibliography, Analysis (in French)

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

| Philosophy | |

|---|---|

| Topics | Category listings | Eastern philosophy · Western philosophy | History of philosophy (ancient • medieval • modern • contemporary) |

| Lists | Basic topics · Topic list · Philosophers · Philosophies · Glossary · Movements · More lists |

| Branches | Aesthetics · Ethics · Epistemology · Logic · Metaphysics · Political philosophy |

| Philosophy of | Education · Economics · Geography · Information · History · Human nature · Language · Law · Literature · Mathematics · Mind · Philosophy · Physics · Psychology · Religion · Science · Social science · Technology · Travel ·War |

| Schools | Actual Idealism · Analytic philosophy · Aristotelianism · Continental Philosophy · Critical theory · Deconstructionism · Deontology · Dialectical materialism · Dualism · Empiricism · Epicureanism · Existentialism · Hegelianism · Hermeneutics · Humanism · Idealism · Kantianism · Logical Positivism · Marxism · Materialism · Monism · Neoplatonism · New Philosophers · Nihilism · Ordinary Language · Phenomenology · Platonism · Positivism · Postmodernism · Poststructuralism · Pragmatism · Presocratic · Rationalism · Realism · Relativism · Scholasticism · Skepticism · Stoicism · Structuralism · Utilitarianism · Virtue Ethics |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.