Difference between revisions of "Plains Indians" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

===Indian wars=== | ===Indian wars=== | ||

European expansion into the plains and mountains by miners, ranchers, and settlers led to increasing conflicts with the Plains Indians. Many tribes fought the whites at one time or another, but the [[Sioux]] provided the significant opposition to encroachment on tribal lands. Led by resolute, militant leaders, such as [[Red Cloud]] and [[Crazy Horse]], the Sioux were skilled at high-speed mounted warfare, having learned to ride horses in order to hunt bison. | European expansion into the plains and mountains by miners, ranchers, and settlers led to increasing conflicts with the Plains Indians. Many tribes fought the whites at one time or another, but the [[Sioux]] provided the significant opposition to encroachment on tribal lands. Led by resolute, militant leaders, such as [[Red Cloud]] and [[Crazy Horse]], the Sioux were skilled at high-speed mounted warfare, having learned to ride horses in order to hunt bison. | ||

| − | [[Image:Tatanka Lyotake.jpg|thumb|right| | + | [[Image:Tatanka Lyotake.jpg|thumb|right|200px|[[Sitting Bull]], [[Lakota]] chief.]] |

Conflict with the Plains Indians continued through the [[American Civil War|Civil War]]. The [[Dakota War of 1862]] was the first major armed engagement between the U.S. and the Sioux. After six weeks of fighting in Minnesota led by Chief [[Taoyateduta]] (Little Crow), over 300 Sioux were convicted of [[murder]] and [[rape]] by U.S. military tribunals and sentenced to death. Most of the [[death sentence]]s were commuted, but on December 26, 1862, in [[Mankato, Minnesota]], 38 Dakota Sioux men were [[hanging|hanged]] in what is still today the largest mass [[capital punishment|execution]] in U.S. history (Carley], 1961). | Conflict with the Plains Indians continued through the [[American Civil War|Civil War]]. The [[Dakota War of 1862]] was the first major armed engagement between the U.S. and the Sioux. After six weeks of fighting in Minnesota led by Chief [[Taoyateduta]] (Little Crow), over 300 Sioux were convicted of [[murder]] and [[rape]] by U.S. military tribunals and sentenced to death. Most of the [[death sentence]]s were commuted, but on December 26, 1862, in [[Mankato, Minnesota]], 38 Dakota Sioux men were [[hanging|hanged]] in what is still today the largest mass [[capital punishment|execution]] in U.S. history (Carley], 1961). | ||

Revision as of 01:53, 22 November 2008

The Plains Indians are the Indigenous peoples who live on the plains and rolling hills of the Great Plains of North America. They are often thought of as the archetypal American Indians, riding on horseback, hunting buffalo, and riding into battle wearing long feathered headdresses.

Languages

Consisting of a large number of different tribes, the Plains Indians spoke a variety of languages. These include languages from the Algonquian, Siouan, Caddoan, Ute-Aztecan, Athabaskan, and Kiowa-Tanoan languages. Thus, for example, the Sioux, Crow, Omaha, Osage, Ponca, and Kansa spoke variations of the Siouan language while the Arapaho, Blackfoot, and Cheyenne spoke Algonquian languages.

Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL) is a sign language formerly used as an auxiliary interlanguage among these Plains Indians tribes whose spoken languages were so different. As nomadic peoples they encountered other tribes speaking other languages and the sign language developed to permit communication among them. Involving the use of hand and finger positions to represent ideas, PISL consists of symbolic representations that were understood by the majority of the tribes in the Plains. It has been suggested that this silent form of communication was of particular importance in their hunting culture, as it permitted communication without disturbing their prey. Given that their targets were buffalo living in huge herds that traveled great distances, many hunters were needed and they had to travel far to find them. Thus, the more universal sign language supported cooperation among different tribes without requiring a common spoken language (U.S. Department of the Interior 2003).

In 1885, it was estimated that there were over 110,000 “sign-talking Indians,” including Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapaho. By the 1960s, there remained a “very small percentage of this number” (Tomkins 1969). There are few PISL signers alive today.

History

Plains Indians are so called because they roamed across the Great Plains of North America. This region extends from the Mississippi River in the east to the Rocky Mountains in the west, and from present-day Canadian provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta in the north to central Texas in the south. The area is primarily treeless grassland. In the wetter parts, in the Mississippi valley, there are tall grasses and this region is also known as the prairies.

The Plains Indians can be divided into two broad classifications, which overlap to some degree. The first group were fully nomadic, following the vast herds of bison, although some tribes occasionally engaged in agriculture—primarily growing tobacco and corn. The Blackfoot, Arapaho, Assiniboine, Cheyenne, Comanche, Crow, Gros Ventre, Kiowa, Lakota, Lipan, Plains Apache (or Kiowa Apache), Plains Cree, Sarsi, Sioux, Shoshone, and Tonkawa belong in this nomadic group.

The second group of Plains Indians (sometimes referred to as Prairie Indians as they inhabited the Prairies) were semi-sedentary tribes who, in addition to hunting bison, lived in villages and raised crops. These included the Arikara, Hidatsa, Iowa, Kaw (or Kansa), Mandan, Omaha, Osage, Otoe, Pawnee, Ponca, and Wichita.

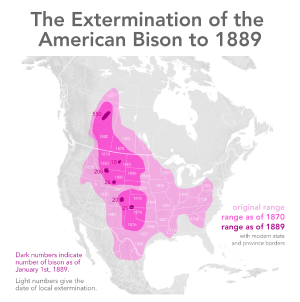

Bison was essential to the survival of all the Plains Indians. It is estimated that there were about 30 million bison in North America in the 1500s. The National Bison Association lists over 150 traditional Native American uses for bison products, besides food (NBA 2006).

After European contact

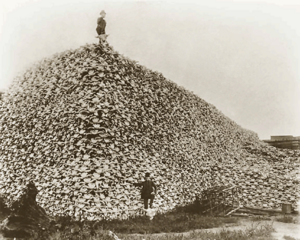

As Americans of European descent moved into Native American lands, the bison were significantly reduced through overhunting. Some of the reasons for this were to free land for agriculture and cattle ranching, to sell the hides of the bison, to deprive hostile tribes of their main food supply, and for what was considered sport. The worst of the killing took place in the 1870s and the early 1880s. By 1890, there were fewer than 1,000 bison in North America (Nowak 1983).

There were government initiatives at the federal and local level to starve the population of the Plains Indians by killing off their main food source, the bison. The Government promoted bison hunting for various reasons: to allow ranchers to range their cattle without competition from other bovines and to weaken the Indian population and pressure them to remain on reservations (Moulton and Sanderson 1998). The herds formed the basis of the economies of local Plains tribes of Native Americans for whom the bison were a primary food source. Without bison, the Native Americans would be forced to leave or starve.

The railroad industry also wanted bison herds culled or eliminated. Herds of bison on tracks could damage locomotives when the trains failed to stop in time. Herds often took shelter in the artificial cuts formed by the grade of the track winding though hills and mountains in harsh winter conditions. As a result, bison herds could delay a train for days.

As the great herds began to wane, proposals to protect the bison were discussed. But these were discouraged since it was recognized that the Plains Indians, often at war with the United States, depended on bison for their way of life. By 1884, the American bison was close to extinction. Together with forced confinement in reservations, the traditional Plains Indians way of life was essentially over.

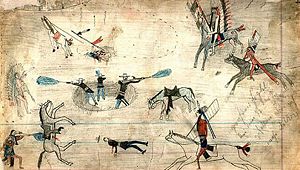

Indian wars

European expansion into the plains and mountains by miners, ranchers, and settlers led to increasing conflicts with the Plains Indians. Many tribes fought the whites at one time or another, but the Sioux provided the significant opposition to encroachment on tribal lands. Led by resolute, militant leaders, such as Red Cloud and Crazy Horse, the Sioux were skilled at high-speed mounted warfare, having learned to ride horses in order to hunt bison.

Conflict with the Plains Indians continued through the Civil War. The Dakota War of 1862 was the first major armed engagement between the U.S. and the Sioux. After six weeks of fighting in Minnesota led by Chief Taoyateduta (Little Crow), over 300 Sioux were convicted of murder and rape by U.S. military tribunals and sentenced to death. Most of the death sentences were commuted, but on December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota, 38 Dakota Sioux men were hanged in what is still today the largest mass execution in U.S. history (Carley], 1961).

In 1864, one of the more infamous Indian War battles took place, the Sand Creek Massacre. A locally raised militia attacked a village of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians in southeast Colorado and killed and mutilated an estimated 150 men, women, and children. The Indians at Sand Creek had been assured by the U.S. Government that they would be safe in the territory they were occupying, but anti-Indian sentiments by white settlers were running high. Later congressional investigations resulted in short-lived U.S. public outcry against the slaughter of the Native Americans.[1]

In 1875, the last serious Sioux war erupted, when the Dakota gold rush penetrated the Black Hills. The U.S. Army did not keep miners off Sioux (Lakota) hunting grounds; yet, when ordered to take action against bands of Sioux hunting on the range, according to their treaty rights, the Army moved vigorously. In 1876, after several indecisive encounters, General George Custer found the main encampment of the Lakota and their allies at the Battle of Little Big Horn. Custer and his men — who were separated from their main body of troops — were all killed by the far more numerous Indians who had the tactical advantage. They were led in the field by Crazy Horse and inspired by Sitting Bull's earlier vision of victory.

The Ghost Dance, originally a peaceful spiritual movement, played a significant role in instigating the Wounded Knee massacre in 1890, which resulted in the deaths of at least 153 Lakota Sioux (Utley 2004). While most followers of the Ghost Dance understood Wovoka’s role as being that of a teacher of pacifism and peace, others did not. An alternate interpretation of the Ghost Dance tradition is seen in the so-called Ghost Shirts, which were special garments rumored to repel bullets through spiritual power. Chief Kicking Bear brought this concept to his own people, the Lakota Sioux, in 1890 (Kehoe 2006).

Performances of the Ghost Dance ritual frightened the supervising agents of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), who had been given the responsibility of supplementing the Sioux with food and hiring white farmers as teachers for the people as they adjusted to reservation life. Kicking Bear was forced to leave Standing Rock, but when the dances continued unabated, Agent McLaughlin asked for more troops, claiming that Hunkpapa spiritual leader Sitting Bull was the real leader of the movement. Thousands of additional U.S. Army troops were deployed to the reservation. In December, Sitting Bull was arrested on the reservation for failing to stop his people from practicing the Ghost Dance (Kehoe 2006). During the incident, a Sioux witnessing the arrest fired at one of the soldiers prompting an immediate retaliation; this conflict resulted in deaths on both sides, including the loss of Sitting Bull himself.

Big Foot, a Miniconjou leader on the U.S. Army’s list of trouble-making Indians, was stopped while en route to convene with the remaining Sioux chiefs. U.S. Army officers forced him and his people to relocate to a small camp close to the Pine Ridge Agency so that the soldiers could more closely watch the old chief. That evening, December 28, the small band of Sioux erected their tipis on the banks of Wounded Knee Creek. The following day, during an attempt by the officers to collect any remaining weapons from the band, one young and deaf Sioux warrior refused to relinquish his arms. A struggle followed in which a rifle was discharged and the U.S. forces opened fire; the Sioux responded by taking up previously confiscated weapons. When the fighting was over, 25 U.S. soldiers lay dead, many killed by friendly fire, amongst the 153 dead Sioux, most of whom were women and children (Kehoe 2006). This ended the Indian Wars. The spirit of the Sioux was crushed, the Ghost Dancers soon stopped dancing, and the U. S. Census Bureau announced that there was no longer a frontier on the maps—the Great Plains (apart from a few scattered reservations) now belonged to the United States (Waldman 2006).

Culture

The nomadic Plains Indian tribes survived on hunting, and bison was their main food source. American buffalo, or simply buffalo, is the commonly used (but inaccurate) name for the American Bison, and this group are sometimes referred to as part of the "Buffalo Culture." Bison were the chief source for items which Indians made from their flesh, hide and bones, such as food, cups, decorations, crafting tools, knives, and clothing. Not a single part of the animal was thrown away.

The tribes kept moving following the bison on their seasonal and grazing migrations. The Plains Indians created tipis because they were easily disassembled and allowed the nomadic life of following game. Prior to the introduction of horses, they used dogs to pull their belongings loaded on simple V-shaped sleds, known as "travois." Native horses had died out in prehistoric times, and so the introduction of horses by the Spanish made a significant change in their lifestyle. When escaped Spanish horses were obtained, the Plains tribes rapidly integrated them into their daily lives, wealth, and hunting techniques. They fully adopted a horse culture in the eighteenth century (Waldman 2006).

Hunting

Although the Plains Indians hunted other animals, such as elk or antelope, bison was their primary game food source. Before horses were introduced, hunting was a more complicated process. They would surround the bison, and then try to herd them off cliffs or into places where they could be more easily killed. The tribesmen might build a corral and herd the buffalo into it to confine them in a space where they could be killed.

Prior to their adoption of guns, the Plains Indians hunted with spears, bows and arrows, and various forms of clubs. When horses, brought by the Spanish to America, escaped and started breeding in the wild, the Indians quickly learned how to capture and train them. Their ability to ride horses made hunting (and warfare) much easier. With horses, the Indians had the means and speed to stampede or overtake the bison. They continued to use bows and arrows after the introduction of firearms, because guns took too long to reload and were too heavy. In the summer, many tribes gathered for hunting in one place. The main hunting seasons were fall, summer, and spring. In winter harsh snow and mighty blizzards made it almost impossible to kill the bison.

Tipis

A tipi, the traditional home of many of the Plains Indians, is a conical tent originally made of animal skins or birch bark. The tipi was durable, provided warmth and comfort in winter, was dry during heavy rains, and was cool in the heat of summer.

Tipis consist of four elements: a set of poles, a hide cover, an optional lining, and a door. Ropes and pegs are used to bind the poles, close the cover, attach the lining and door, and anchor the resulting structure to the ground. Tipis are distinguished by opening at the top and the smoke flaps, which allow the dweller to cook and heat themselves with an open fire, and the lining that is primarily used in the winter, providing insulation as well as allowing a source of fresh air to fire and dwellers. Tipis are designed to be easily set up to allow camps to be moved to follow game migrations, especially the bison. The long poles could be used to construct a dog- or later horse-pulled travois. They could be disassembled and packed away quickly when a tribe decided to move, and could be reconstructed quickly when the tribe settled in a new area. This portability was important to those Plains Indians who had a nomadic lifestyle.

Some tipis were painted in accordance with traditional tribal designs and often featured geometric portrayals of celestial bodies and animal designs, or to depict personal experiences, such as war or hunting. In the case of a dream or vision quest, “ceremonies and prayers were first offered, and then the dreamer recounted his dream to the priests and wise men of the community… Those known to be skilled painters were consulted, and the new design was made to fit anonymously within the traditional framework of [the tribe’s] painted tipis” (Goble 2007). While most tepees were not painted, many were decorated with pendants and colored medallions. Traditionally these were embroidered with dyed porcupine quills; more modern versions are often beaded. Bison horns and tails, tufts of buffalo and horse hair, bear claws, and buckskin fringe were also used to decorate tipi covers. These attachments are often referred to as “tepee ornaments”.

Headdress

Feathered war bonnets (or headdresses) were a military decoration developed by the Plains Indians. A chief's war bonnet is comprised of feathers received for good deeds to his community and is worn in high honor. Each feather would represent a good deed. The eagle was considered the greatest and most powerful of all birds and thus, the finest bonnets were made out of its feathers.

The bonnet was only worn on special occasions and was highly symbolic. Its beauty was of secondary importance; the bonnet's real value was in its power to protect the wearer.

The bonnet had to be earned through brave deeds in battle because the feathers signified the deeds themselves. Some warriors might obtain only two or three honor feathers in their whole lifetime, so difficult were they to earn. The bonnet was also a mark of highest respect because it could never be worn without the consent of the leaders of the tribe. A high honor, for example, was received by the warrior who was the first to touch an enemy fallen in battle, for this meant the warrior was at the very front of fighting. Feathers were notched and decorated to designate an event and told individual stories such as killing, scalping, capturing an enemy's weapon and shield, and whether the deed had been done on horseback or foot.

After about ten honors had been won, the warrior went out to secure the eagle feathers with which to make his bonnet. In some tribes these had to be purchased from an individual given special permission to hunt the bird; a tail of twelve perfect feathers could bring the seller as much as a good horse. Some tribes permitted a warrior to hunt his own eagles. This was a dangerous and time-consuming mission and meant that he had to leave the tribe and travel to the high country where the bird could be found. When the destination had been reached, ceremonies were conducted to appeal to the spirits of the birds to be killed.

Counting coup

Plains Indian warriors won prestige, known as "Counting coup," by acts of bravery in the face of the enemy. Any blow struck against the enemy counted as a coup, but the most prestigious acts included touching an enemy warrior, with the hand or with a "coup stick," then escaping unharmed. Counting coup could also involve stealing from the enemy. Risk of injury or death was required to count coup.

Coups were recorded by notches in the coup stick, or by feathers in the headdress of a warrior who was rewarded with them for an act of bravery.

The term is of French origin from the noun coup (pronounced /ku/) which means a hit, a blow or a strike. The expression can be seen as referring to "counting strikes".

Art

Plains Indians used traditional pictographs to keep historical records and serve as mnemonic reminders for storytelling. A traditional male art form, warriors drew pictographic representations of heroic deeds and sacred visions rocks and animal skins, which served to designate their positions in the tribe.

In captivity following the Indian Wars, a number of Plains Indians, particularly the Kiowa were able to use the lined pages of the white man's record keeping books (ledgers) for their artworks, resulting in "ledger art." At Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Florida Captain Richard Henry Pratt initiated an educational experiment as an alternative to standard imprisonment, culminating in his founding of the Carlisle Indian School in 1879. The Plains Indian leaders followed Pratt's rules and met his educational demands even as they remained true to their own identities, practicing traditional dances and ceremonies (Lookingbill 2006). In addition to regular studies Pratt encouraged them to pursue their native arts and to sell the products, keeping the profits for themselves. For these former warriors their art was not just a way of making money but a form of resistance. The warrior-artists of Fort Marion preserved their history in their traditional pictographic representations, drawn on the the very records, the ledgers, that recorded the expansion of the Euro-American lifestyle (Wong 1992).

Religion

The Plains Indians followed no single religion. Animist beliefs were an important part of a their life, as they believed that all things possessed spirits. Their worship was centered on one main god, in the Sioux language Wakan Tanka (the Great Spirit). The Great Spirit had power over everything that had ever existed. Earth was also important, as she was the mother of all spirits.

There were also people that were wakan, or blessed, who were also called shaman. To become wakan, your prayers must be answered by the Great Spirit, or you must see a sign from him. Wakan were thought to possess great power. One of their jobs was to heal people, which is why they are also sometimes called "medicine men." The shamans were considered so important that they were the ones who decided when the time was right to hunt.

Sacred objects

A peace pipe, also called a "calumet" or "medicine pipe," is a ceremonial smoking pipe used by many tribes including those of the Plains Indians, traditionally as a token of peace. A common material for calumet pipe bowls is red pipestone or catlinite, a fine-grained easily-worked stone of a rich red color of the Coteau des Prairies, west of the Big Stone Lake in South Dakota. The quarries were formerly neutral ground among warring tribes; many sacred traditions are associated with the locality. A type of herbal tobacco or mixture of herbs was usually reserved for special smoking occasions, with each region's people using the plants that were locally considered to have special qualities or a culturally condoned basis for ceremonial use.

Plains Indians believed that some objects possessed spiritual or talismanic power. One such item was the medicine bundle, which was a sack carrying items believed by the owner to be important. Items in the sack might include rocks, feathers, and more. Another object of great spiritual power was the shield. The shield was the most prized possession of any warrior, and he decorated it with many paintings and feathers. The spirits of animals drawn on the shield were thought to protect the owner.

Vision quest

Plains Indians sought spiritual help in many aspects of their life; usually by means of a vision quest. This involved going to a lonely spot where the individual would fast and ask for aid. If successful, a spirit-being would appear in a dream or supernatural vision and give instructions that would lead to success in the individual's endeavor.

Commonly both men and women participated in vision quests; children would undertake their first vision quest at an age as young as six or seven years although the age of the first quest varied from tribe to tribe. In some tribes the first vision quest was a rite of passage, marking an individual's transition from childhood to adulthood. In some tribes only males participated in vision quests; menarche (the onset of menstruation) marking the transition to adulthood for females.

Sun Dance

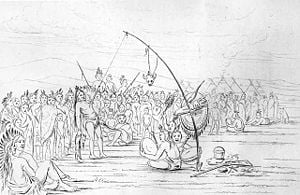

The Sun Dance is a ceremony practiced by a number of Native Americans. This ceremony was one of the most important rituals practiced by The North American Plains Indians. Each tribe has its own distinct rituals and methods of performing the dance, but many of the ceremonies have features in common, including dancing, singing, praying, drumming, the experience of visions, fasting, and in some cases piercing of the chest or back. Most notable for early Western observers was the piercing many young men endure as part of the ritual. Frederick Schwatka wrote about a Sioux Sun Dance he witnessed in the late 1800s:

Each one of the young men presented himself to a medicine-man, who took between his thumb and forefinger a fold of the loose skin of the breast—and then ran a very narrow-bladed or sharp knife through the skin—a stronger skewer of bone, about the size of a carpenter's pencil was inserted. This was tied to a long skin rope fastened, at its other extremity, to the top of the sun-pole in the center of the arena. The whole object of the devotee is to break loose from these fetters. To liberate himself he must tear the skewers through the skin, a horrible task that even with the most resolute may require many hours of torture (Schwatka 1889).

In fact, the object of being pierced is to sacrifice one's self to the Great Spirit, and to pray while connected to the Tree of Life, a direct connection to the Great Spirit. Breaking from the piercing is done in one moment, as the man runs backwards from the tree at a time specified by the leader of the dance. A common explanation, in context with the intent of the dancer, is that a flesh offering, or piercing, is given as part of prayer and offering for the improvement of one's family and community.

Ghost Dance

Noted in historical accounts as the Ghost Dance of 1890, the Ghost Dance was a religious movement incorporated into numerous Native American belief systems. The traditional ritual used in the Ghost Dance, the circle dance, has been used by many Native Americans since prehistoric times, but was first performed in accordance with Jack Wilson's teachings among the Nevada Paiute in 1889. The practice swept throughout much of the American West, quickly reaching areas of California and Oklahoma. As the Ghost Dance spread from its original source, Native American tribes synthesized selective aspects of the ritual with their own beliefs, often creating change in both the society that integrated it and the ritual itself.

At the core of the movement was the prophet of peace Jack Wilson, known as Wovoka among the Paiute, who prophesied a peaceful end to white American expansion while preaching messages of clean living, an honest life, and cross-cultural cooperation. The Sioux variation on the Ghost Dance tended towards millenarianism, an innovation which distinguished the Sioux interpretation from Jack Wilson's original teachings.

Through Native Americans and some Anglo Americans, Jack Wilson’s message spread across much of the western portion of the United States. Early in the religious movement many tribes sent members to investigate the self-proclaimed prophet, while other communities sent delegates only to be cordial. Regardless of their motivations, many left believers and returned to their homeland preaching his message. The Ghost Dance was also investigated by many Mormons from Utah, for whom the concepts of the Native American prophet were familiar and often accepted (Kehoe 2006).

Contemporary Plains Indians

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carlson, Paul H. The Plains Indians. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-89096-828-4

- Taylor, Colin E. The Plains Indians: A Cultural and Historical View of the North American Plains Tribes of the Pre-Reservation Period. New York: Crescent Books, 1994. ISBN 0517142503

- Brown, Dee. 1970. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. Owl Books.

- Du Bois, Cora. 1939. The 1870 Ghost Dance. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Osterreich, Shelley Anne. 1991. The American Indian Ghost Dance, 1870 and 1890. New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

- Stannard, David E. 1992. American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press.

- Waldman, Carl. 2006. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816062744

- Berlo, Janet Catherine. 1997. Plains Indian Drawings. Tribal Arts. Retrieved October 28, 2008.

- Lookingbill, Brad D. 2006. War Dance at Fort Marion: Plains Indian War Prisoners. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806137391.

- Wong, Hertha Dawn. 1992. Sending My Heart Back Across the Years: Tradition and Innovation in Native American Autobiography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195069129.

- Berlo, Jane Catherine. 1996. Plains Indian Drawings 1865-1935. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0810937420.

- Tomkins, William. [1931] 1969. Indian sign language. New York, NY: Dover Publications 1969.

- Schwatka, Frederick. [1889] 1994. The Sun-Dance of the Sioux. Century Magazine 39: 753-759. Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- Kehoe, Alice Beck. 2006. The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization. Waveland Press. ISBN 978-1577664536

- Utley, Robert M. 2004. The Last Days of the Sioux Nation. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300103166

- NBA. 2008. Byproducts: Nature's Bountiful Commissary for the Plains Indians. National Bison Association website. Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- Nowak, Ronald M. 1999. Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801857899

- Moulton, Michael, and James Sanderson. 1998. Wildlife Issues in a Changing World. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 1566703514

- U.S. Department of the Interior. 2003. Plains Indian Sign Language: A Memorial to the Conference September 4-6, 1940, Browning, Montana. Indian Arts and Crafts Board. Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- Goble, Paul. 2007. Tepee: Home of the Nomadic Buffalo Hunters. World Wisdom Books. ISBN 193331639X

- Carley, Kenneth. 1961. The Sioux Uprising of 1862. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society.

External links

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Plains_Indians history

- Sun_Dance history

- Ghost_Dance history

- Plains_Indian_Sign_Language history

- Counting_coup history

- War_bonnet history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Utley and Washburn, 228.