Difference between revisions of "Dagestan" - New World Encyclopedia

Mike Butler (talk | contribs) |

Mike Butler (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

===Scythians=== | ===Scythians=== | ||

[[Image:Scythia-Parthia 100 BC.png|350px|thumb|right|Approximate extent of Scythia and [[Sarmatia]] in the 1st century B.C.E.]] | [[Image:Scythia-Parthia 100 BC.png|350px|thumb|right|Approximate extent of Scythia and [[Sarmatia]] in the 1st century B.C.E.]] | ||

| − | The [[Scythian]]s, a nation of horse-riding [[nomadic pastoralists]] who spoke an [[Iranian languages]]dominated the [[Pontic steppe]], a vast [[steppe]]lands stretching from north of the [[Black Sea]] as far as the east of the [[Caspian Sea]], from around 770 B.C.E. to 660 C.E. During the [[5th century B.C.E.|5th]] to [[3rd century B.C.E.|3rd centuries]] BCE the Scythians evidently prospered, obtaining their wealth from their control over the [[slave trade|slave-trade]] from the north to Greece, although they also grew grain, and shipped [[wheat]], flocks, and [[cheese]] to Greece. | + | The [[Scythian]]s, a nation of horse-riding [[nomadic pastoralists]] who spoke an [[Iranian languages]] dominated the [[Pontic steppe]], a vast [[steppe]]lands stretching from north of the [[Black Sea]] as far as the east of the [[Caspian Sea]], from around 770 B.C.E. to 660 C.E. During the [[5th century B.C.E.|5th]] to [[3rd century B.C.E.|3rd centuries]] BCE the Scythians evidently prospered, obtaining their wealth from their control over the [[slave trade|slave-trade]] from the north to Greece, although they also grew grain, and shipped [[wheat]], flocks, and [[cheese]] to Greece. |

Westward expansion brought the Scythians into conflict with [[Philip II of Macedon]] (reigned 359 to 336 B.C.E.), who took military action against the Scythians in 339 B.C.E. Scythian leader Ateas died in battle and his empire disintegrated. In the aftermath of this defeat, the [[Celts]] seem to have displaced the Scythians from the [[Balkans]], while in south Russia a kindred tribe, the [[Sarmatians]], gradually overwhelmed them. | Westward expansion brought the Scythians into conflict with [[Philip II of Macedon]] (reigned 359 to 336 B.C.E.), who took military action against the Scythians in 339 B.C.E. Scythian leader Ateas died in battle and his empire disintegrated. In the aftermath of this defeat, the [[Celts]] seem to have displaced the Scythians from the [[Balkans]], while in south Russia a kindred tribe, the [[Sarmatians]], gradually overwhelmed them. | ||

Revision as of 07:04, 19 August 2007

| Republic of Dagestan (English) Республика Дагестан (Russian) | |

|---|---|

Location of the Republic of Dagestan in Russia | |

| Coat of Arms | Flag |

Coat of arms of Dagestan |

Flag of Dagestan |

| Anthem: National Anthem of the Republic of Dagestan | |

| Capital | Makhachkala |

| Established | January 20 1921 |

| Political status Federal district Economic region |

Republic Southern North Caucasus |

| Code | 05 |

| Area | |

| Area - Rank |

50,300 km² 52nd |

| Population (as of the 2021 Census) | |

| Population - Rank - Density - Urban - Rural |

2,576,531 inhabitants 22nd 51.2 inhab. / km² 42.8% 57.2% |

| Official languages | Russian, languages of the peoples of Dagestan |

| Government | |

| President | Mukhu Aliyev |

| Chairman of the Government | Shamil Zaynalov |

| Legislative body | People's Assembly |

| Constitution | Constitution of the Republic of Dagestan |

The Republic of Dagestan IPA: [dæɡɪˈstɑːn (IntEng), ˈdeɪɡəstæn (AmEng)] (Russian: Респу́блика Дагеста́н; Avar: Дагъистанлъул ДжумхIурият, Daɣistanłul Džumħuriyat), older spelling Daghestan, is a federal subject of the Russian Federation (a republic).

The republic is situated on the eastern end of the North Caucasus mountains along the western shore of the Caspian Sea. It is the southernmost part of Russia.

It is the largest republic of Russia in the North Caucasus, both in area and population.

The word Daghestan or Daghistan means "country of mountains", it is derived from the Turkic word dağ meaning mountain and Persian suffix -stan meaning "land of". The spelling Dagestan is a transliteration of the Russian name and is rather modern.

The republic's name in Persian and Arabic is داغستان.

Geography

Dagestan borders the Republic of Kalmykia to the north, the Chechen Republic to the west, Stavropol Krai to the northwest, Azerbaijan to the south, Georgia to the south-west, and the Caspian Sea to the east.

The land area is 19,420 square miles (50,300 km²), or about the size of Slovakia or the combined size of Massachusetts and Vermont in the United States.

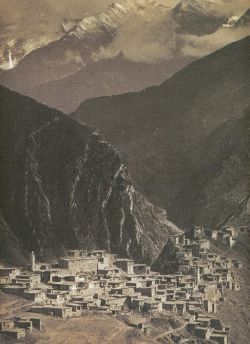

Dagestan comprises five geographical regions. The first region, which takes up the southern half of the republic, consists of the Caucasus Mountains, the crest of which marks Dagestan's southern border. The highest point of the territory is located here, at Mount Bazar Duzu, which is 14,652 feet (4466 meters) above sea level. To the north of the mmain mountain ranges is a triangle of rugged mountains known as the Dagestan Interior Highland.

The second region, to the north of the mountains, is a zone of foreland hills, about 12 to 25 miles (19km to 40km) wide and rising to 2000–3000 feet (600–900 meters). The third region is a narrow coastal plain between the mountains and the Caspian Sea. The fourth area is a continuation of the coastal plain northward.

The fifth region is a rolling, sandy plain called the Nogay steppe, as far as the Kuma River, which forms the republic's northern boundary.

The climate is hot and dry in the summer but the winters are hard in the mountain areas. The average January temperature in the lowland is 25.5°F (-3.6°C), while the average July temperature is about 74.3°F (23.5°C). Rainfall in the interior mountainous areas averages 20–30 inches (510–760mm) annually, while rainfall in hot and dry north is with only 8–10 inches (200–250mm).

There are over 1800 rivers in the republic. The Terek is a major river in the Northern Caucasus. It rises in Georgia near the juncture of the The Greater Caucasus Mountain Range and the Khokh Range, then flows north through North Ossetia and the city of Vladikavkaz, through Chechnya and Dagestan before dividing into two branches which empty into the Caspian Sea. Below the city of Kizlyar it forms a swampy river delta around 60 miles (100km) wide. The river is a key natural asset in the region, being used for irrigation and hydroelectric power in its upper reaches. Other major rivers include the Sulak River, and Samur River.

Large areas of the southern mountains are devoid of vegetation. The foreland hills have dense oak, beech, hornbeam, maple, poplar, and black alder, with a grass steppe vegetation on the lower slopes. Vegetation in the semidesert north is dominated by sagebrush.

Dagestan is rich in oil, natural gas, coal, and many other minerals. The rivers are a potential source for hydroelectric power.

The Caspian Sea is considered the ecologically most devastated area in the world because of severe air, soil, and water pollution; soil pollution results from oil spills, from the use of DDT as a pesticide, and from toxic defoliants used in the production of cotton.

The capital Makhachkala, population 462,412, is located on the western shore of the Caspian Sea. Makhachkala's historic predecessor was the town of Tarki, now a mere suburb, whose history goes back to the fifteenth century and possibly much earlier. The modern city of Makhachkala was founded in 1844 as a fortress; town status was granted in 1857. The original name of the city was Petrovskoye, after the Russian tsar Peter the Great who visited the region in 1722. The city incurred major damage during an earthquake on May 14, 1970.

History

Prior to the first century, the vast lands of southern Russia were home to scattered tribes, such as Proto-Indo-Europeans and Scythians. The Proto-Indo-Europeans are a hypothetical group of people whose existence from around 4000 B.C.E. is inferred from their language, Proto-Indo-European. They were both pastoral and nomadic, domesticating cattle and horses, they had carts, with solid wheels, but not yet chariots with spoked wheels, the chief of their pantheon was *dyeus ph2tēr (lit. "sky father", and they they composed and recited heroic poetry.

Scythians

The Scythians, a nation of horse-riding nomadic pastoralists who spoke an Iranian languages dominated the Pontic steppe, a vast steppelands stretching from north of the Black Sea as far as the east of the Caspian Sea, from around 770 B.C.E. to 660 C.E. During the 5th to 3rd centuries B.C.E. the Scythians evidently prospered, obtaining their wealth from their control over the slave-trade from the north to Greece, although they also grew grain, and shipped wheat, flocks, and cheese to Greece.

Westward expansion brought the Scythians into conflict with Philip II of Macedon (reigned 359 to 336 B.C.E.), who took military action against the Scythians in 339 B.C.E. Scythian leader Ateas died in battle and his empire disintegrated. In the aftermath of this defeat, the Celts seem to have displaced the Scythians from the Balkans, while in south Russia a kindred tribe, the Sarmatians, gradually overwhelmed them.

Sarmatians

The Sarmatians were a people originally of Iranian stock. Mentioned by classical authors, they migrated from Central Asia to the Ural Mountains around the fifth century B.C.E. and eventually settled in most of southern European Russia and the eastern Balkans. The Sarmatians flourished from the time of Herodotus and allied partly with the Huns when they arrived in the fourth century C.E. Herodotus describes the Sarmatians' physical appearance as blond, stout and tanned; in short, pretty much as the Scythians and Thracians were seen by the other classical authors.

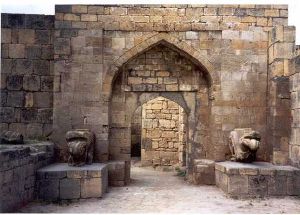

Caucasian Albania

Caucasian Albania was an ancient kingdom, which existed on the territory of present-day Republic of Azerbaijan and southern Dagestan from the late fourth century B.C.E. Caucasian Albanians were one of the Ibero-Caucasian peoples, the ancient and indigenous population of modern southern Dagestan and Azerbaijan. Its capital was at Derbent, a city is situated on a thin strip of land (three kilometres) between the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus mountains. Other important centres were at Chola, Toprakh Qala, and Urtseki. The northern parts were held by a confederation of pagan tribes. In 66 B.C.E., following the defeat of the Armenian king Tigranes II at the hand of the Romans, the Armenian empire lost most of its territory.

Romans invade

In 65 B.C.E. the Roman general Pompey invaded Albania at the head of his army. Between 83 and 93 C.E. in the reign of Domitian a detachment of the Legio XII Fulminata was sent to the Caucasus to support the allied kingdoms of Iberia and Albania in a war against Parthia. During the reign of Roman emperor Hadrian (117-138) Albania was invaded by the Alans, an Iranian nomadic group.

Sassanid domination

In 252-253 C.E., Caucasian Albania along with Iberia and Armenia was conquered by the Persian Sassanid Empire (226-651). Albania was mentioned among the Sassanian provinces listed in the trilingual inscription of Shapur I at Naqsh-e Rustam.

In the middle of the fourth century the king of Albania Urnayr arrived in Armenia and was baptized by Gregory the Illuminator, but Christianity spread in Albania only gradually, and the Albanian king remained loyal to the Sassanids. After the partition of Armenia between Byzantium and Persia (in 387 C.E.), Albania, as an ally of Sassanid Persia, regained all the right bank of the river Kura up to river Araxes, including Artsakh and Utik.

Sassanian king Yazdegerd II passed an edict requiring all the Christians in his empire to convert to Mazdaism, (a form of Zoroastrianism) fearing that Christians might ally with Roman Empire, which had recently adopted Christianity. This led to rebellion of Albanians, along with Armenians and Iberians.

In a battle that took place in 451 in the Avarayr field, the allied forces of the Armenian, Albanian and Iberian kings, devoted to Christianity, suffered defeat at the hands of the Sassanid army. Many of the Albanian nobility ran to the mountainous regions of Albania, particularly to Artsakh, that became a center for resistance to Sassanid Iran. The religious center of the Albanian state also moved here. However, the Albanian king Vache, a relative of Yazdegerd II, converted to the official religion of the Sasanian empire, but soon reverted to Christianity.

In the fifth century the Sassanids constructed a strong citadel at Derbent, known henceforward as the Caspian Gates.

Arab and Seljuk domination

In the middle of the seventh century C.E., the kingdom was overrun by the Arabs and, like all Islamic conquests at the time, incorporated into the Caliphate. The Albanian king Javanshir, the most prominent ruler of Mihranid dynasty, fought against the Arab invasion of caliph Uthman on the side of the Sasanid Iran. Facing the threat of the Arab invasion on the south and the Khazar offensive on the north, Javanshir had to recognize the Caliph’s suzerainty. The Arabs then reunited the territory with Armenia under one governor.

From the eighth century, Caucasian Albania existed as the principalities of Arranshahs and Khachin, along with various Caucasian, Iranian and Arabic principalities: the Principality of Shaddadids, the Principality of Shirvan, the Principality of Derbent, etc. Most of the region was ruled by the Sajid Dynasty of Azerbaijan from 890 to 929.

Although the local population rose against the Arabs of Derbent in 905 and 913, Islam was eventually adopted in urban centres, such as Samandar and Kubachi (Zerechgeran), from where it steadily penetrated into the highlands.

Christian Sarir

The northern part of Dagestan was overrun by the Huns, followed by the Eurasian Avars. It is not clear whether the latter were instrumental in the rise of the Christian kingdom in Central Dagestan highlands. Known as Sarir, this Avar-dominated medieval Christian state lastd from the fifth century to the 12th century in the mountainous regions of modern-day Dagestan. Its name is derived from the Arabic word for "throne" and refers to a golden throne which was viewed as a symbol of royal authority.

Sarir neighboured the Khazars to the north, the Alans to the east, the Georgians and Derbent to the south. As the state was Christian, Arab historians erroneously viewed it as a dependency of the Byzantine Empire. The capital of Sarir was the city of Humradzh, tentatively identified with the modern-day village Khunzakh. The king resided in a remote fortress at the top of a mountain. Due to Muslim pressure and internal disunity, Sarir disintegrated in the early twelfth century, giving way to the Avar Khanate. By the fifteenth century, Albanian Christianity had died away, leaving a tenth-century church at Datuna as the sole monument to its existence.

Khazaria

Khazaria, also known as Khazar khaganate or Khazar khanate was the country of the Khazars, neighboring the Byzantine Empire in the southwest, Kievan Rus' in the northwest, Volga Bulgaria in the north, and Azerbaijan in the southeast. This Turkic people adopted Judaism in the eighth or ninth century, becoming the only Jewish state ever without Abrahamic descent. As an independent state, Khazaria existed between about 652 and 1016. Its supreme ruler was known by the title khagan. Its last khagan was named George Tsul. Much of Khazaria was covered by steppe land. Khazaria bordered the Caspian Sea and Black Sea. The Volga River (known as Itil or Atil) passed through eastern Khazaria.

Avar Khanate

The Avar Khanate was a long-lived Muslim state which controlled Central Dagestan from the early thirteenth century to the nineteenth century. Following the downfall of the Christian kingdom of Sarir in the early 12th century, the Caucasian Avars, who had migrated there from Khwarezm, underwent a process of peaceful Islamization.

Military tensions escalated in 1222, when the region was invaded by the pagan Mongols under Subutai. Although the Avars pledged their support to Muhammad II of Khwarezm in his struggle against the Mongols, there is no documentation for the Mongol invasion of the Avar lands. As historical clues are so scarce, it is probably fruitless to speculate whether the Avars were the agents of the Mongol influence in the Caucasus and whether they were entrusted with the task of levying tribute for the khan.

The Khanate of Avaristan survived Tamerlane's raid in 1389.

As the Mongol authority gradually eroded, new centres of power emerged in Kaitagi and Tarki. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, legal traditions were codified, mountainous communities (djamaats) obtained a considerable degree of autonomy, while the Kumyk potentates (shamhals) asked for the Tsar's protection.

In the eighteenth century, the steady weakening of Tarki fostered the ambitions of the Avar khans, whose greatest coup was the defeat of the 100,000-strong army of Nadir Shah of Persia in September 1741. Avar sovereigns managed to expand their territory at the expense of free communities in Dagestan and Chechnya.

The reign of Umma-Khan (1774-1801) marked the zenith of the Avar ascendancy in the Caucasus. Among the potentates who paid tribute to Umma-Khan were the rulers of Derbent, Shaki, Quba, Baku, Shirvan, Akhaltsikhe, and even Erekle II of Georgia.

Russian protection

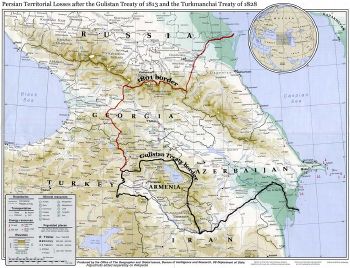

Russians intensified their hold in the region in the eighteenth century, when Peter the Great annexed maritime Dagestan in the course of the First Russo-Persian War (1722-23). Although the territories were returned to Persia in 1735, the Persian Expedition of 1796 resulted in the Russian capture of Derbent in 1796.

In 1803, within two years after Umma-Khan's death, the khanate voluntarily submitted to Russian authority, but it took Persia a decade to recognize all of Dagestan as the Russian possession (Treaty of Gulistan in 1813). Yet the Russian administration disappointed and embittered freedom-loving highlanders. The institution of heavy taxation, coupled with the expropriation of estates and the construction of fortresses, electrified the Avar population into rising under the aegis of the radical Muslim Imamate, led by Ghazi Mohammed (1828-32), Gamzat-bek (1832-34) and Shamil (1834-59).

Caucasian wars

The Caucasian War of 1718–1864, was a series of military actions waged by the Russian Empire against a number of territories and tribal groups in Caucasia including Chechnya, Dagestan and the Adyghe (Circassians) as Russia sought to expand southward. The writers Mikhail Lermontov and Leo Tolstoy took part in the hostilities, and the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin referred to it in his Byronic poem The Prisoner of Caucasus (1821). The Russian invasion was met with fierce resistance.

During 1825–1830 there was little activity, since Russia was engaged in wars with Turkey and Persia. After considerable successes in both wars, Russia resumed fighting in the Caucasus. They were again met with resistance, notably led by Ghazi Mollah, Gamzat-bek and Hadji Murad. Imam Shamil followed them. He led the mountaineers from 1834. In 1845, Shamil's forces achieved their most dramatic success when they withstood a major Russian offensive. Imperial Russia was distracted by the Crimean War (1853– 1856) against an alliance of France, the United Kingdom, the Kingdom of Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire, on the Crimean Peninsula. The Caucasian War raged until 1864, when Shamil was captured, when the Avar Khanate was abolished, and the Avar District was instituted instead.

In the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878), Russia sought to gain access to the Mediterranean Sea by capturing the Balkan Peninsula from the Ottoman Empire. Dagestan and Chechnya profited from this to rise against Imperial Russia for the last time.

Mountainous republic

During the Russian Civil War (1917-1922), the region became part of the short-lived Republic of the Mountaineers of the North Caucasus (1917–1920), a shortlived state situated in the Northern Caucasus, now forming the republics of Chechnya, Ingushetia, North Ossetia-Alania, and Dagestan of the Russian Federation. With a population of about one million, its capital was initially at Vladikavkaz, then Nazran and finally Buynaksk.

Dagestan ASSR

After more than three years of fighting White movement reactionaries and local nationalists, the Dagestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic ASSR was proclaimed on January 20, 1921. The ASSRs had a status lower than the republics of the Soviet Union, but higher than the autonomous oblasts and autonomous okrugs. Unlike the union republics, the autonomous republics did not have a right to disaffiliate themselves from the Union.

Although the Dagestan ASSR was proclaimed in 1921, Soviet rule was slow to become established and its presence was not truly felt until after the end of World War II, because of territorial isolation. Until 1938 mountain paths were the only way out, and a linguistic barrier existed. Marxist-Leninist theory and the principles of collectivization were first conveyed to the Avars.

Soviet leader Stalin's industrialization largely bypassed Dagestan and the economy stagnated, making the republic the poorest region in Russia. However, Dagestanis escaped the mass deportation inflicted on their Chechen neighbours and others in the Stalinist era.

After Soviet collapse

Since the Soviet Union collapsed, corruption increased, while oil and caviar mafias flourished. Kidnappings and violence are common, firearms are everywhere and assassinations are a regular. Moscow blames Chechen-based separatism, while others blame profiteering, lawlessness, and a gun culture.

Muslim insurgency

Dagestani Muslims, who combine Sufism combined with local tradition, have tried to avoid the conflict that has afflicted Chechnya. But in the late 1990s, more radical and militant elements, linked with Wahhabism, gained influence. Chechen warlords have led armed operations in Dagestan, first in 1995 and 1996 when Shamil Basayev and Salman Raduyev crossed the border and seized hundreds of hostages in hospitals in the Dagestani towns of Budennovsk and Kizlyar. There was tension in 1998 when two mountain villages near the Chechen border sought to introduce Shari'ah law in 1998.

In 1999, Muslim fundamentalists under Basayev, together with local converts and exiles from the 1998 uprising, declared an independent state in parts of Dagestan and Chechnya and called on Muslims to take up arms against Russia in a holy war. They also called for the arrest of Magomedali Magomedov, the repulic's leader at the time, accusing him of working with the Russians. Hundreds of combatants and civilians died. Russian forces subsequently reinvaded Chechnya later that year.

Since 2000, the republic has sustained numerous bombings targeted at the Russian military. Dozens died in 2002 when bombers targeted a Russian military parade in Kaspiysk, and Russian forces have since been the target of numerous smaller scale attacks. At least 10 died in a bomb blast in the capital, Makhachkala in July 2005. Violence continues, with several people killed in multiple explosions and shootings through 2006.

Government and politics

The Republic of Dagestan is one of the 21 republics of the Russian Federation, all of which are reputed to have a high degree of autonomy on most issues.

According to the Constitution of Dagestan, which was adopted in 1994, the highest executive authority lies with the State Council, comprising representatives of 14 ethnicities. The ethnicities represented there are Aguls, Avars, Azeris, Chechens, Dargins, Kumyks, Laks, Lezgins, Russians, Rutuls, Tabasarans, Tats, and Tsakhurs. The members of the State Council are appointed by the Constitutional Assembly of Dagestan for a term of four years. The State Council appoints the members of the Government.

The Parliament of Dagestan is the People's Assembly, consisting of 121 deputees elected for a four-year term. The People's Assembly is the highest executive and legislative body of the republic.

The chairman of the State Council was the highest executive post in the republic, and that position was held by Magomedali Magomedov until February 20, 2006, when the People's Assembly passed a resolution terminating this post and disbanded the State Council. Russian President Vladimir Putin had ethnic Caucasian Avar Mukhu Aliyev installed as the first President of Dagestan. Formerly the speaker of the Republic's parliament, he is responsible for dealing with Muslim insurgency spilling over from Chechnya.

Dagestan has 41 districts, 10 cities and towns, 19 urban settlements, 694 selsoviet (administrative unit), 1605 rural localities, and 46 uninhabited rural localities.

Economy

Agriculture is the biggest economic sector, at 35 percent of the economy.Livestock raising is the main activity, especially sheep farming. Only 15 percent of the land is cultivable. Hillsides are terraced. Vegetables, cherries, apricots, apples, pears, and melons are grown in irrigated areas of the Terek River delta region and the coastal plain. Cereal crops include wheat, corn (maize), and rice.

Fishing is important along the Caspian Sea coast.

Industry contributes 24 percent of GDP. Dagestan has oil and natural gas, coal, iron ore, and nonferrous and rare metals, but the rugged terrain has limited development of the republic's mineral and hydroelectric-power resources. Important industries are petroleum and natural-gas resources of the coastal plain near Makhachkala and Izberbash, machine building, power engineering, instrument making, the production of building materials, timber working, glassmaking, wine making, and food processing. Ironworking and rug making are traditional handicrafts.

Construction made up 26 percent of GDP, services 9 percent, transport and communications 5 percent and other sectors 1 percent. Hydroelectric power is supplied by stations on the Karakoysu River, the Terek,and on the Sulak.

Dagestan's major exports are petroleum, fish, wine, brandy, and various garden fruits. Dagestan has economic cooperation with Iran.

Railways link Dagestan with Moscow, Baku, Astrakhan, and Gudermes. Sea routes cross the Caspian to Makhachkala, Dagestan's chief port.

Demographics

Unlike most other parts of Russia, the population of Dagestan, which was 2,576,531 in 2002, is rapidly growing. The terrirory continues to be the least urbanized republic in the Caucasus — 42.8 percent is urban and 57.2 percent rural. Dagestan has the highest average life expectancy in the Russian Federation, which is 65.87 years for the total population.

Ethnicity

Because its mountainous terrain impedes travel and communication, Dagestan is unusually ethnically diverse, and still largely tribal.

Seventy-five percent of the inhabitants still live in remote, often inaccessible mountain villages. The largest nationalities are the 758,438 Caucasian Avars (29.4 percent), who live in the south and the west of the country; the 425,526 Dargins (16.5 percent) in the central regional; and the 336,698 Lezghins (13.1 percent), who live in the south. The smallest ethnic group (only 24,298 or 0.9 percent) is the Ratuls, who spread over four alpine villages in the south. In addition to the indigenous Dagestanis, there are some 120,875 Russians (4.7 percent), most of whom live in the capital, Makhachkala, and the other large cities.

The Kumyks, 365,804 (14.2 percent), are a Turkic people occupying the Kumyk plateau in north Dagestan and south Terek, and the lands bordering the Caspian Sea. They practice folk Islam, with some religious rituals that trace back to pre-Islamic times. During the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries C.E. the Kumyks had an independent kingdom, based at Tarki, and ruled by a leader called the Shamkhal.

The Nogai People, 38,168 (1.5 percent), sometimes called Caucasian Mongols, are a Turkic people group, and an important ethnic group in the Daghestan region. They are descendants of Kipchaks who mingled with their Mongol conquerors and formed the Nogai Horde. They have scant beard growth, and are shorter than most people of the Caucasus. The average height for males is 160cm. They often have almond-shaped eyes, flat faces, high noses, and sometimes blue eyes.

Azeris make up 4.3 percent, while there are 40 or so tiny groups such as the Hinukh, numbering 200, or the Akhwakh, who are members of a complex family of indigenous Caucasians. Notable are also the Hunzib or Khunzal people who live in only four towns in the interior. Other ethnic groups each account for less than 0.5 percent of the total population.

Religion

With such ethnic diversity, 90.4 percent of the population are Muslims, with Christians accounting for the remainder. As with much of the Caucasus region, Dagestan's native Islam consists of Sufi orders that have been in place for centuries. Sufism spread Islam to countries outside Arabia. Though Islam had spread north into the Caucasus and Central Asia during the Arab invasions of the seventh and eighth centuries, Sufism penetrated Central Asia in the twelfth century and into the northern Caucasus in the early 18th century. Its success was in great part due to its ability to adapt some local beliefs or customs into Islam.

Under the Soviet regime, although religious practice was banned, the public continued such rites as marriage, burial, and circumcision in the Islamic way

The appearance of a Sunni group, the Wahhabis, which has been active in Central Asia and Muslim regions of the Caucasus, has caused resentment among the various Sufi orders. Sufi masters especially object to the Wahhabis, who are teaching that these masters and the tombs of previous masters do not deserve any special respect. The Wahhabis have a reputation for going beyond simply teaching its form of Islam. The group is usually well funded, helps construct mosques and brings in Korans printed in local languages. The Wahhabis, generally, receive their money from Saudi Arabia.

Language

Each of Dagestan's 33 ethnic groups has its own distinct language. The three main linguistic groups are Turkic, Persian, and aboriginal Caucasian, a complicated language, leading specialists to believe that its speakers always lived there. The people practice what linguists call vertical polylingualism, in which the ethnic group inhabiting the village at the top of the mountain speaks its own language or dialect, plus the language of the village below.

Russian is the lingua franca, though before the 1917 revolution it was Arabic. In 1938 the alphabets of all Dagestani nations with a written language were converted to Cyrillic.

The Avar language belongs to the Avar-Andi-Tsez subgroup of the Alarodian Northeast Caucasian (language family. The writing is based on the Cyrillic alphabet, which replaced the Arabic script used before 1927 and the Latin script used between 1927 and 1938. More than 60 percent of Avars living in Dagestan speak Russian as their second language.

The Dargin language has three principal dialects, and Dargwa peoples use a modified version of the Cyrillic alphabets to write their language, which is one of the literary languages of Dagestan. Lezgi belongs to the Northeast Caucasian (Dagestan) language family, is not an official language, but is one of six literary languages of Dagestan.

Kumyk is a Turkic language, spoken by about 200,000 Kumyks in Dagestan. Kumyk was written using Arabic script until 1928, Latin script was used in 1928-1938, and Cyrillic since then.

Men and women

Dagestanis, like most mountain people, are a hardy breed. Both women and men are small, slight, and wiry, with narrow hands and feet and chiseled features. The greatest sign of beauty and status is acknowledged to be a mouthful of glittering gold teeth. The veil was never worn in Dagestan. Women lower their eyes in the company of men.

Marriage and the family

Marriage outside tribal or ethnic groups is discouraged, but intermarriage is becoming more common among urban dwellers and between members of certain villages. Traditionally Avars marry at about age 15. The parents take most responsibility in the selection of a partner, although a young man can say who he wants to marry. First cousins may marry, and girls do not marry a young man of lower social rank, or someone outside the village group. Weddings are celebrated with dances, songs, and sometimes horse races.

In the Soviet period, a registered civil marriage became obligatory. The newlyweds lived with the husband’s parents, but with separate living quarters. In divorce, the woman traditionally retained all her dowry, and the children remained with the father. This Sharia-based custom was changed to follow Soviet law so that the children remained with the mother. The formal right to divorce used to rest with the man but now a marriage can be dissolved by either party. Polygamy was traditional and has resurged after the collapse of the Soviet system.

The Avars, unlike other peoples of the Caucasus, lived in nuclear families. Inheritance was from father to son, while women inherited one-third of the total inheritance, although Avars, especially urban dwellers, followed Soviet laws.

Education

Russia's free, widespread and in-depth educational system, inherited with almost no changes from the Soviet Union, produces 100 percent literacy. Preschool education is well developed, with four-fifths of children aged three to six attending day nurseries or kindergartens. School is compulsory for nine years, from age seven, leading to a basic general education certificate. Two or three years are required for the secondary-level certificate. Non-Russian pupils are taught in their own language, although Russian is compulsory at the secondary schools

Ninety seven percent of children receive their compulsory nine-year basic or complete 11-year education in Russian. Entry to higher education is selective and highly competitive. Most undergraduate courses require five years. As a result of great emphasis on science and technology in education, Russian medical, mathematical, scientific, and space and aviation research is generally of a high order.

Class

Avar society was segmentation into classes. A clan-based aristocracy (nutsbi, uzden) constituted a patrician class, while freed and the serfs (or "slaves") made up a lower class. Under Russia, a new aristocracy emerged based on service, and after the 1917 Revolution society was divided into workers, peasants, and intellectuals. Traditional class divisions persisted into the Soviet period, when communist elites had special access to goods, services, and housing. Since the Soviet Union collapsed, while oil and caviar mafias flourished.

Culture

Provide any relevant cultural information.

Architecture

Art

Cinema

Cuisine

Khingal is the Dagestan national dish of small dumplings boiled in ram's broth. Depending on the cook's nationality, the dumplings can be oval or round, filled with meat or cheese, and served with a garlic or sour cream sauce.

Clothing

Dagestani men are known for traditional leather boots and wasp-waisted, tight-fitting tunics. To make their waists even smaller, they bind their tunics with the skin of a freshly slaughtered sheep. The bourka, a shaggy, full-length cape made with layers of felt to resist rain - and bullets - is an all-purpose mountaineer's outfit. Rural women wear long-sleeved floral dresses over full pantaloons. As required by Islamic tradition, they cover their heads with a scarf.

Literature

Music

There is a Dagestani Philharmonic Orchestra and a State Academic Dance Ensemble. Gotfrid Hasanov, said to be the first professional composer from Dagestan, wrote Khochbar, the first Dagestani opera, in 1945.

Dagestani folk dances include a fast paced dance called the lezginka. Lezginka or Lezghinka is a folk dance popular among many people in the Caucasus Mountains. It derives its names from the Lezgin people; nevertheless, Azerbaijanis, Circassians, Abkhazians, Mountain Jews, Caucasian Avars, the Russian Kuban and Terek Cossacks and many other tribes have their own versions.

Extensive notes about Daghestani music can be found in the liner notes of the CD release Ay Lazzat, Oh Pleasure. Songs and melodies from Daghestan (Pan 2031 CD, Pan Records, the Netherlands, 1995). The disc particularly features the vocals of two famous Daghestani chanteuses, Zuhra Shandieva (1966-1993), who mainly sang traditional music in the Nogai language, and Sanijat Sultanova (b. 1967), singing in the Avar language.

Performing arts

Sport

References and notes

See also

- Music of Dagestan

- Former countries in Europe after 1815

External links

- Dagestan Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed August 17, 2007.

- Dagestan BBC Country Profile, accessed August 17, 2007.

- Defender of Dagestan world andi.com, accessed August 19, 2007.

- "The North Caucasus," Russian Analytical Digest No. 22 (5 June 2007)

- (Russian) Official governmental website of Dagestan

- (Russian) Official Website of the Chairman of the State Council of Dagestan

- University of Texas maps of the Dagestan region

- Radio Free Europe discusses religious tension in Dagestan

- ISN Case Study: The North Caucasus on the Brink (August 2006)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.