Einstein, Albert

(claimed) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (70 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| + | {{epname|Einstein, Albert}} | ||

{{Infobox Scientist | {{Infobox Scientist | ||

| name = Albert Einstein | | name = Albert Einstein | ||

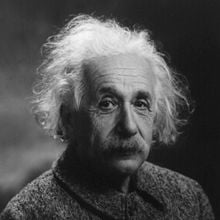

| − | | image = Albert_Einstein_Head.jpg | + | | image = Albert_Einstein_Head.jpg |

| − | | image_width = | + | | image_width = 220px |

| caption = Photographed by Oren J. Turner (1947) | | caption = Photographed by Oren J. Turner (1947) | ||

| − | | birth_date = | + | | birth_date = {{birth date|1879|3|14}} |

| birth_place = [[Ulm]], [[Württemberg]], [[Germany]] | | birth_place = [[Ulm]], [[Württemberg]], [[Germany]] | ||

| − | | death_date = | + | | death_date = {{death date and age|1955|4|18|1879|3|14}} |

| − | | death_place = [[Princeton, New Jersey|Princeton]], [[New Jersey]] | + | | death_place = [[Princeton, New Jersey|Princeton]], [[New Jersey]], [[United States|U.S.]] |

| − | | residence = [[Germany]], [[Italy]], [[Switzerland]], [[United States|USA]] | + | | residence = {{flagicon|Germany}} [[Germany]], {{flagicon|Italy}} [[Italy]], <br/>{{flagicon|Switzerland}}[[Switzerland]], {{flagicon|United States}} [[United States of America|USA]] |

| − | | nationality = [[Germany | + | | nationality = {{flagicon|Germany}} [[Germany]], {{flagicon|Switzerland}}[[Switzerland]], <br/>{{flagicon|United States}} [[United States of America|USA]] |

| + | | ethnicity = [[Jewish]] | ||

| field = [[Physics]] | | field = [[Physics]] | ||

| − | | work_institution = [[Swiss]] [[Patent Office]] [[Bern|(Berne)]]</ | + | | work_institution = [[Swiss]] [[Patent Office]] [[Bern|(Berne)]]<br/>[[University of Zürich|Univ. of Zürich]]<br/> [[Charles University of Prague|Charles Univ.]]<br/>[[Prussian Academy of Sciences|Prussian Acad. of Sciences]]<br/> [[Kaiser Wilhelm Institute|Kaiser Wilhelm Inst.]]<br/>[[University of Leiden|Univ. of Leiden]]<br/>[[Institute for Advanced Study|Inst. for Advanced Study]] |

| − | | alma_mater = [[ETH Zürich]] | + | | alma_mater = [[ETH Zürich]] |

| − | | known_for | + | | doctoral_advisor = [[Alfred Kleiner]] |

| − | | prizes = [[Image:Nobel.svg|20px]] [[Nobel Prize in Physics]] (1921)</ | + | | known_for = [[General relativity]]<br/>[[Special relativity]]<br/>[[Brownian motion]]<br/>[[Photoelectric effect]]<br/>[[Mass-energy equivalence]]<br/>[[Einstein field equations]]<br/>[[classical unified field theories|Unified Field Theory]]<br/> [[Bose–Einstein statistics]]<br/> [[EPR paradox]] |

| + | | prizes = [[Image:Nobel prize medal.svg|20px]] [[Nobel Prize in Physics]] (1921)<br/>[[Copley Medal]] (1925)<br/>[[Max Planck medal]] (1929) | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | |||

| − | '''Albert Einstein''' ( | + | '''Albert Einstein''' (March 14, 1879 – April 18, 1955) was a [[Germany|German]]-born [[theoretical physics|theoretical physicist]]. He is best known for his [[theory of relativity]] and specifically the equation <math>E = m c^2</math>, which indicates the relationship between [[mass]] and [[energy]] (or [[mass-energy equivalence]]). Einstein received the 1921 [[Nobel Prize in Physics]] "for his services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the [[photoelectric effect]]." |

| − | + | Einstein's many contributions to physics include his [[special theory of relativity]], which reconciled [[mechanics]] with [[electromagnetism]], and his [[general theory of relativity]] which extended the [[principle of relativity]] to non-uniform motion, creating a new theory of [[gravitation]]. His other contributions include [[physical cosmology|relativistic cosmology]], [[capillarity|capillary action]], [[critical opalescence]], [[classical physics|classical problems]] of [[statistical mechanics]] and their application to [[Quantum mechanics|quantum theory]], an explanation of the [[Brownian motion|Brownian movement]] of [[molecule]]s, [[transition rule|atomic transition]] [[probability|probabilities]], the quantum theory of a [[monatomic gas]], [[thermodynamics|thermal]] properties of [[light]] with low [[radiation]] density (which laid the foundation for the [[photon]] theory), a theory of radiation including [[stimulated emission]], the conception of a [[classical unified field theories|unified field theory]], and the geometrization of [[physics]]. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | [[Works by Albert Einstein]] include more than 50 scientific papers and also non-scientific books. In 1999 Einstein was named [[Time (magazine)|''TIME'']] magazine's "[[Person of the Century]]," and a poll of prominent physicists named him the greatest physicist of all time. In [[popular culture]], the name "Einstein" has become synonymous with [[genius]]. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Youth and schooling== |

| − | + | Albert Einstein was born into a [[Jewish]] family in [[Ulm]], [[Württemberg]], [[Germany]]. His father was Hermann Einstein, a salesman and engineer. His mother was Pauline Einstein (née Koch). Although Albert had early [[language delay|speech difficulties]], he was a top student in elementary school.<ref>Thomas Sowell, ''The Einstein Syndrome: Bright Children Who Talk Late.'' (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2001, ISBN 0465081401).</ref> | |

| − | [[ | + | In 1880, the family moved to [[Munich]], where his father and his uncle founded a company, Elektrotechnische Fabrik J. Einstein & Cie that manufactured electrical equipment, providing the first lighting for the [[Oktoberfest]] and cabling for the Munich suburb of [[Schwabing]]. The Einsteins were not observant of Jewish religious practices, and Albert attended a [[Catholic school|Catholic elementary school]]. At his mother's insistence, he took [[violin]] lessons, and although he disliked them and eventually quit, he would later take great pleasure in [[Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|Mozart's]] [[violin sonata]]s. |

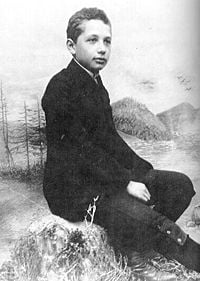

| − | + | [[Image:Eins1.jpg|thumb|left|200px| Albert Einstein in 1894, taken before the family moved to Italy]] | |

| + | When Albert was five, his father showed him a pocket [[compass]]. Albert realized that something in empty space was moving the needle and later stated that this experience made "a deep and lasting impression".<ref>P. A. Schilpp, ''Albert Einstein - Autobiographical Notes.'' (Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 1979).</ref> As he grew, Albert built [[model (physical)|models]] and [[machine|mechanical devices]] for fun, and began to show a talent for [[mathematics]]. | ||

| − | + | In 1889, family friend Max Talmud (later: Talmey), a medical student,<ref name=HarvChemAE>Dudley Herschbach, [http://www.chem.harvard.edu/herschbach/Einstein_Student.pdf HarvardChem-Einstein-PDF Einstein as a Student.] ''Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Harvard University''. Retrieved December 17, 2007.</ref> introduced the ten-year-old Albert to key science and [[philosophy]] texts, including [[Immanuel Kant|Kant's]] ''[[Critique of Pure Reason]]'' and [[Euclid]]'s ''[[Euclid's Elements|Elements]]'' (Einstein called it the "holy little geometry book").<ref name=HarvChemAE/> From Euclid, Albert began to understand [[deductive reasoning]] (integral to [[theoretical physics]]), and by the age of 12, he learned [[Euclidean geometry]] from a school booklet. Soon thereafter he began to investigate [[calculus]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Albert | + | In his early teens, Albert attended the new and progressive [[Luitpold Gymnasium]]. His father intended for him to pursue [[electrical engineering]], but Albert clashed with authorities and resented the school regimen. He later wrote that the spirit of learning and creative thought were lost in strict [[rote learning]]. |

| − | + | In 1894, when Einstein was 15, his father's business failed, and the Einstein family moved to [[Italy]], first to [[Milan]] and then, after a few months, to [[Pavia]]. During this time, Albert wrote his first scientific work, "The Investigation of the State of [[aether theories|Aether]] in [[magnetic field|Magnetic Fields]]." Albert had been left behind in Munich to finish high school, but in the spring of 1895, he withdrew to join his family in Pavia, convincing the school to let him go by using a doctor's note. | |

| − | + | Rather than completing [[high school]], Albert decided to apply directly to the [[ETH Zürich]], the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in [[Zurich]], [[Switzerland]]. Without a school certificate, he was required to take an entrance examination. He did not pass. Einstein wrote that it was in that same year, at age 16, that he first performed his famous [[thought experiment]], visualizing traveling alongside a beam of light.<ref>Albert Einstein, ''Autobiographical Notes (Centennial ed.)'' (Chicago, IL: Open Court, 1979 ISBN 0875483526), 48–51. description of chasing a light beam thought experiment </ref> | |

| − | + | The Einsteins sent Albert to [[Aarau]], [[Switzerland]] to finish secondary school. While lodging with the family of Professor Jost Winteler, he fell in love with the family's daughter, Sofia Marie-Jeanne Amanda Winteler, called "Marie." (Albert's sister, Maja, his confidant, later married Paul Winteler.) In Aarau, Albert studied [[James Clerk Maxwell|Maxwell's]] [[electromagnetic theory]]. In 1896, he graduated at age 17, renounced his German [[citizenship]] to avoid military service (with his father's approval), and finally enrolled in the [[mathematics]] program at ETH. On February 21, 1901, he gained Swiss citizenship, which he never revoked. Marie moved to [[Olsberg, Switzerland]] for a teaching post. | |

| − | In | + | In 1896, Einstein's future wife, [[Mileva Marić]], also enrolled at ETH, as the only woman studying mathematics. During the next few years, Einstein and Marić's friendship developed into romance. Einstein's mother objected because she thought Marić "too old," not Jewish, and "physically defective." This conclusion is from Einstein's correspondence with Marić. Lieserl is first mentioned in a letter from Einstein to Marić (who was abroad at the time of Lieserl's birth) dated February 4, 1902, from Novi Sad, Hungary.<ref>''Collected papers'' Vol. 1, (document 134).</ref><ref>[http://www.einstein-website.de/biographies/einsteinlieserl.html Short life history: Lieserl Einstein-Maric]''Einstein website''. </ref> Her fate is unknown. |

| − | + | Einstein graduated in 1900 from ETH with a degree in physics. That same year, Einstein's friend [[Michele Besso]] introduced him to the work of [[Ernst Mach]]. The next year, Einstein published a paper in the prestigious ''[[Annalen der Physik]]'' on the [[capillary action|capillary forces]] of a straw.<ref>Albert Einstein, Folgerungen aus den Capillaritätserscheinungen (Conclusions Drawn from the Phenomena of Capillarity). ''Annalen der Physik'' 4 (1901):513.</ref> | |

| − | + | ==The Patent Office== | |

| + | [[File:Casa de Albert Einstein.JPG|thumb|right|200px|The 'Einsteinhaus' in [[Bern]] where Einstein lived with Mileva on the first floor during his ''Annus Mirabilis'']] | ||

| + | Following graduation, Einstein could not find a teaching post. After almost two years of searching, a former classmate's father helped him get a job in [[Bern]], at the Federal Office for Intellectual Property, the patent office, as an assistant [[patent examiner|examiner]]. His responsibility was evaluating [[patent]] applications for electromagnetic devices. In 1903, Einstein's position at the Swiss Patent Office was made permanent, although he was passed over for promotion until he "fully mastered machine technology".<ref name="GalisonClocks">Peter Galison, Einstein's Clocks: The Question of Time. ''Critical Inquiry'' 26(2) (2000):355–389.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Einstein's college friend, Michele Besso, also worked at the patent office. With friends they met in Bern, they formed a weekly discussion club on [[science]] and [[philosophy]], jokingly named "The [[Olympia Academy]]." Their readings included [[Henri Poincaré|Poincaré]], [[Ernst Mach|Mach]] and [[David Hume|Hume]], who influenced Einstein's scientific and philosophical outlook.<ref name="GalisonClocksMaps">Peter Galison, ''Einstein's Clocks, Poincaré's Maps: Empires of Time.'' (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2003, ISBN 0393020010).</ref> | |

| − | + | While this period at the patent office has often been cited as a waste of Einstein's talents, or as a temporary job with no connection to his interests in [[physics]], the historian of science [[Peter Galison]] has argued that Einstein's work there was connected to his later interests. Much of that work related to questions about transmission of electric signals and electrical-mechanical synchronization of [[time]]: two technical problems of the day that show up conspicuously in the [[thought experiments]] that led Einstein to his radical conclusions about the nature of [[light]] and the fundamental connection between space and time.<ref name="GalisonClocks"/><ref name="GalisonClocksMaps"/> | |

| − | + | Einstein married [[Mileva Marić]] on January 6, 1903, and their relationship was, for a time, a personal and intellectual partnership. In a letter to her, Einstein wrote of Mileva as "a creature who is my equal and who is as strong and independent as I am." There has been debate about whether Marić influenced Einstein's work; most historians do not think she made major contributions, however. On May 14, 1904, Albert and Mileva's first son, [[Hans Albert Einstein]], was born. Their second son, [[Eduard Einstein]], was born on July 28, 1910. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==The ''Annus Mirabilis''== | |

| + | {{main|Annus Mirabilis Papers}} | ||

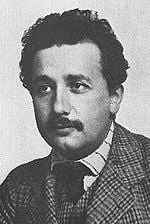

| + | [[Image:Einstein patentoffice.jpg|thumbnail|right|150px| Albert Einstein, 1905]] | ||

| + | In 1905, while working in the patent office, Einstein published four times in the ''[[Annalen der Physik]],'' the leading German physics journal. These are the papers that history has come to call the ''[[Annus Mirabilis Papers]]'': | ||

| + | *His paper on the particulate nature of light put forward the idea that certain experimental results, notably the [[photoelectric effect]], could be simply understood from the postulate that light interacts with matter as discrete "packets" ([[quanta]]) of energy, an idea that had been introduced by [[Max Planck]] in 1900 as a purely mathematical manipulation, and which seemed to contradict contemporary wave theories of light. This was the only work of Einstein's that he himself pronounced as "revolutionary."<ref>Albert Einstein, On a Heuristic Viewpoint Concerning the Production and Transformation of Light. ''Annalen der Physik'' 17 (1905):132–148. This annus mirabilis paper on the photoelectric effect was received by Annalen der Physik March 18.</ref> | ||

| + | *His paper on [[Brownian motion]] explained the random movement of very small objects as direct evidence of molecular action, thus supporting the [[atomic theory]].<ref>Albert Einstein, On the Motion—Required by the Molecular Kinetic Theory of Heat—of Small Particles Suspended in a Stationary Liquid. ''Annalen der Physik'' 17 (1905):549–560. This annus mirabilis paper on Brownian motion was received May 11</ref> | ||

| + | *His paper on the electrodynamics of moving bodies proposed the radical theory of [[special relativity]], which showed that the independence of an observer's state of motion on the observed [[speed of light]] requires fundamental changes to the [[relativity of simultaneity|notion of simultaneity]]. The consequences of this include the [[spacetime|time-space frame]] of a moving body slowing down and contracting (in the direction of motion) relative to the frame of the observer. This paper also argued that the idea of a [[luminiferous aether]]—one of the leading theoretical entities in physics at the time—was superfluous.<ref>Albert Einstein, On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies. ''Annalen der Physik'' 17 (1905):891–921. This annus mirabilis paper on special relativity received June 30.</ref> | ||

| + | *In his paper on the [[mass-energy equivalence|equivalence of matter and energy]] (previously considered to be distinct concepts), Einstein deduced from his equations of special relativity what would later become the most famous expression in all of science: <math>E = m c^2</math>, suggesting that tiny amounts of mass could be converted into huge amounts of [[energy]].<ref>Albert Einstein, Does the Inertia of a Body Depend Upon Its Energy Content? ''Annalen der Physik'' 18 (1905):639–641. This annus mirabilis paper on mass-energy equivalence was received September 27.</ref> | ||

| − | + | All four papers are today recognized as tremendous achievements—and hence 1905 is known as Einstein's "[[Annus mirabilis|Wonderful Year]]." At the time, however, they were not noticed by most physicists as being important, and many of those who did notice them rejected them outright.<ref>Abraham Pais, ''Subtle is the Lord. The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein.'' (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1982, ISBN 0195204387).</ref> Some of this work—such as the theory of light quanta—would remain controversial for years.<ref>Thomas F. Glick, (ed.), ''The Comparative Reception of Relativity.'' (Boston, MA: D. Reidel, 1987 ISBN 9027724989).</ref> | |

| − | + | At the age of 26, having studied under [[Alfred Kleiner]], Professor of Experimental Physics, Einstein was awarded a [[Doctor of Philosophy|PhD]] by the [[University of Zurich]]. His dissertation was entitled "A new determination of molecular dimensions."<ref>Albert Einstein, "A new determination of molecular dimensions." This Ph.D. thesis was completed April 30 and submitted July 20, 1905.</ref> | |

| − | {{ | + | ==Light and General Relativity== |

| − | + | {{seealso|History of general relativity|Relativity priority dispute}} | |

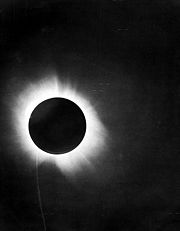

| + | [[Image:1919 eclipse positive.jpg|left|thumb|180px|One of the 1919 eclipse photographs taken during [[Arthur Eddington]]'s expedition, which [[confirmation (epistemology)|confirmed]] Einstein's predictions of the gravitational bending of light.]] | ||

| − | + | In 1906, the patent office promoted Einstein to Technical Examiner Second Class, but he was not giving up on academia. In 1908, he became a [[privatdozent]] at the [[University of Bern]]. In 1910, he wrote a paper on [[critical opalescence]] that described the cumulative effect of light scattered by individual molecules in the atmosphere, i.e., why the sky is blue.<ref>Thomas Levenson, "Genius Among Geniuses, Einstein's Big Idea." Public Broadcasting Service, 2005. </ref> | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | Einstein | + | During 1909, Einstein published "Über die Entwicklung unserer Anschauungen über das Wesen und die Konstitution der Strahlung" ("[[s:The Development of Our Views on the Composition and Essence of Radiation|The Development of Our Views on the Composition and Essence of Radiation]]"), on the [[quantization (physics)|quantization]] of light. In this and in an earlier 1909 paper, Einstein showed that [[Max Planck]]'s [[energy]] [[quanta]] must have well-defined [[momentum|momenta]] and act in some respects as independent, [[point particle|point-like particles]]. This paper introduced the ''[[photon]]'' concept (although the term itself was introduced by [[Gilbert N. Lewis]] in 1926) and inspired the notion of [[wave–particle duality]] in [[quantum mechanics]]. |

| − | + | In 1911, Einstein became an [[associate professor]] at the [[University of Zurich]]. However, shortly afterward, he accepted a full professorship at the [[Charles University in Prague|Charles University of Prague]]. While in [[Prague]], Einstein published a paper about the effects of [[gravity]] on light, specifically the [[gravitational redshift]] and the gravitational deflection of light. The paper appealed to astronomers to find ways of detecting the deflection during a solar eclipse.<ref>Albert Einstein, On the Influence of Gravity on the Propagation of Light. ''Annalen der Physik'' 35 (1911):898–908.</ref> German astronomer [[Erwin Freundlich]] publicized Einstein's challenge to scientists around the world.<ref>Jeffrey Crelinsten, ''Einstein's Jury: The Race to Test Relativity.'' (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0691123103).</ref> | |

| − | + | In 1912, Einstein returned to Switzerland to accept a professorship at his [[alma mater]], the [[ETH]]. There he met mathematician [[Marcel Grossmann]] who introduced him to [[Riemannian geometry]], and at the recommendation of Italian mathematician [[Tullio Levi-Civita]], Einstein began exploring the usefulness of [[general covariance]] (essentially the use of [[tensor]]s) for his gravitational theory. Although for a while Einstein thought that there were problems with that approach, he later returned to it and by late 1915 had published his general theory of relativity in the form that is still used today.<ref>Albert Einstein, Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation (The Field Equations of Gravitation). ''Koniglich Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften'' (1915): 844–847.</ref> This theory explains gravitation as distortion of the structure of [[spacetime]] by matter, affecting the [[inertia]]l motion of other matter. | |

| − | + | After many relocations, Mileva established a permanent home with the children in Zurich in 1914, just before the start of [[World War I]]. Einstein continued on alone to Germany, more precisely to [[Berlin]], where he became a member of the [[Prussian Academy of Sciences|Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften]]. As part of the arrangements for his new position, he also became a professor at the [[University of Berlin]], although with a special clause freeing him from most teaching obligations. From 1914 to 1932 he was also director of the [[Kaiser Wilhelm Institute]] for physics.<ref>Horst Kant, "Albert Einstein and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in Berlin," in Jürgen Renn, ''Albert Einstein - Chief Engineer of the Universe: One Hundred Authors for Einstein'' (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-VCH, 2005, ISBN 3527405747).</ref> | |

| − | + | During [[World War I]], the speeches and writings of [[Central Powers]] scientists were only available to Central Powers academics for [[national security]] reasons. Some of Einstein's work did reach the [[United Kingdom]] and the USA through the efforts of the Austrian [[Paul Ehrenfest]] and physicists in the [[Netherlands]], especially 1902 Nobel Prize-winner [[Hendrik Lorentz]] and [[Willem de Sitter]] of the [[Leiden University]]. After the war ended, Einstein maintained his relationship with the Leiden University, accepting a contract as a ''[[Professor#Netherlands|buitengewoon hoogleraar]]''; he travelled to Holland regularly to lecture there between 1920 and 1930. | |

| − | Einstein' | + | In 1917, Einstein published an article in ''Physikalische Zeitschrift'' that proposed the possibility of [[stimulated emission]], the physical technique that makes possible the [[laser]]}. He also published a paper introducing a new notion, a [[cosmological constant]], into the general theory of relativity in an attempt to model the behavior of the entire [[universe]]. |

| − | + | 1917 was the year astronomers began taking Einstein up on his 1911 challenge from Prague. The [[Mount Wilson Observatory]] in [[California]], USA, published a solar spectroscopic analysis that showed no gravitational redshift. In 1918, the [[Lick Observatory]], also in California, announced that they too had disproven Einstein's prediction, although their findings were not published.<ref name=Crelinsten>Jeffrey Crelinsten, ''Einstein's Jury: The Race to Test Relativity.'' (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0691123103).</ref> | |

| − | + | However, in May 1919, a team led by British astronomer [[Arthur Eddington]] claimed to have confirmed Einstein's prediction of [[gravitational lensing|gravitational deflection of starlight by the Sun]] while photographing a [[solar eclipse]] in [[Sobral, Ceará| Sobral]] northern [[Brazil]] and [[Principe]].<ref name=Crelinsten/> On November 7, 1919, leading British newspaper ''[[The Times]]'' printed a banner headline that read: "Revolution in Science – New Theory of the Universe – Newtonian Ideas Overthrown".<ref>[http://www.nature.com/embor/journal/v4/n3/full/embor779.html Myths in science]. ''EMBO reports'' 4(3):236. Retrieved December 17, 2007.</ref> In an interview Nobel laureate [[Max Born]] praised general relativity as the "greatest feat of human thinking about nature"; fellow laureate [[Paul Dirac]] was quoted saying it was "probably the greatest scientific discovery ever made".<ref>Jürgen Schmidhuber, [http://www.idsia.ch/~juergen/einstein.html Albert Einstein (1879–1955) and the "Greatest Scientific Discovery Ever.] ''IDSIA'', 2006. Retrieved December 21, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | In their excitement, the world media made Albert Einstein world-famous. Ironically, later examination of the photographs taken on the Eddington expedition showed that the experimental uncertainty was of about the same magnitude as the effect Eddington claimed to have demonstrated, and in 1962 a British expedition concluded that the method used was inherently unreliable. The deflection of light during an eclipse has, however, been more accurately measured (and confirmed) by later observations.<ref>[http://www.mathpages.com/rr/s6-03/6-03.htm Bending Light]. ''Math Pages''. Retrieved December 17, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | There was some resentment toward the newcomer Einstein's fame in the scientific community, notably among German physicists, who would later start the ''[[Deutsche Physik]]'' (German Physics) movement.<ref>Klaus Hentschel, & Ann M. Hentschel, ''Physics and National Socialism: An Anthology of Primary Sources.'' (Boston, MA: Birkhaeuser Verlag, 1996, ISBN 3764353120).</ref> | |

| − | + | Having lived apart for five years, Einstein and Mileva divorced on February 14, 1919. On June 2 of that year, Einstein married [[Elsa Einstein|Elsa Löwenthal]], who had nursed him through an illness. Elsa was Albert's [[first cousin]] (maternally) and his [[second cousin]] (paternally). Together the Einsteins raised Margot and Ilse, Elsa's daughters from her first marriage. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==The Nobel Prize== | |

| + | [[Image:Albert Einstein photo 1921.jpg|thumb|left|160px|Einstein, 1921. Age 42.]] | ||

| + | In 1921 Einstein was awarded the [[Nobel Prize in Physics]], "for his services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect." This refers to his 1905 paper on the photoelectric effect: "On a Heuristic Viewpoint Concerning the Production and Transformation of Light," which was well supported by the experimental evidence by that time. The presentation speech began by mentioning "his theory of relativity [which had] been the subject of lively debate in philosophical circles [and] also has astrophysical implications which are being rigorously examined at the present time."<ref>Albert Einstein. Fundamental Ideas and Problems of the Theory of Relativity, Nobel Lectures, Physics 1901–1921, (Amsterdam: Elsevier Publishing Company, 1923).</ref> As per their divorce settlement, Einstein gave the Nobel prize money to his first wife, [[Mileva Marić]], who was struggling financially to support their two sons and her parents. | ||

| − | + | Einstein travelled to [[New York City]] in the United States for the first time on April 2, 1921. When asked where he got his scientific ideas, Einstein explained that he believed scientific work best proceeds from an examination of physical reality and a search for underlying axioms, with consistent explanations that apply in all instances and avoid contradicting each other. He also recommended theories with visualizable results.<ref>Albert Einstein, ''Ideas and Opinions.'' (New York, NY: Random House, 1954, ISBN 0517003937).</ref> | |

| − | + | ==Unified Field Theory== | |

| − | + | [[Image:Max-Planck-und-Albert-Einstein.jpg|thumb|right|200px|[[Max Planck]] presents Einstein with the inaugural [[Max Planck medal]], Berlin June 28, 1929]] | |

| − | + | Einstein's research after general relativity consisted primarily of a long series of attempts to generalize his theory of gravitation in order to unify and simplify the fundamental [[physical law|laws of physics]], particularly gravitation and electromagnetism. In 1950, he described this "[[Unified Field Theory]]" in a ''[[Scientific American]]'' article entitled "On the Generalized Theory of Gravitation."<ref>Albert Einstein, On the Generalized Theory of Gravitation. ''Scientific American'' CLXXXII (4) (1950):13–17.</ref> | |

| − | + | Although he continued to be lauded for his work in theoretical physics, Einstein became increasingly isolated in his research, and his attempts were ultimately unsuccessful. In his pursuit of a unification of the fundamental forces, he ignored mainstream developments in physics (and vice versa), most notably the [[strong nuclear force|strong]] and [[weak nuclear force]]s, which were not well understood until many years after Einstein's death. Einstein's goal of unifying the laws of physics under a single model survives in the current drive for the [[grand unification theory]]. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Einstein | + | ==Collaboration and conflict== |

| − | + | ===Bose–Einstein statistics=== | |

| − | </ref> | + | In 1924, Einstein received a [[statistical mechanics|statistical]] model from [[India]]n physicist [[Satyendra Nath Bose]] which showed that light could be understood as a gas. Bose's statistics applied to some atoms as well as to the proposed light particles, and Einstein submitted his translation of Bose's paper to the ''[[Zeitschrift für Physik]].'' Einstein also published his own articles describing the model and its implications, among them the [[Bose–Einstein condensate]] phenomenon that should appear at very low temperatures.<ref>Albert Einstein, Quantentheorie des einatomigen idealen Gases (Quantum theory of monatomic ideal gases). ''Sitzungsberichte der Preussichen Akademie der Wissenschaften Physikalisch—Mathematische Klasse''. (1924):261–267.</ref> It was not until 1995 that the first such condensate was produced experimentally by [[Eric Cornell]] and [[Carl Wieman]] using [[ultracold atom|ultra-cooling]] equipment built at the [[NIST]]-[[JILA]] laboratory at the [[University of Colorado at Boulder]]. [[Bose–Einstein statistics]] are now used to describe the behaviors of any assembly of "[[boson]]s." Einstein's sketches for this project may be seen in the Einstein Archive in the library of the [[Leiden University]].<ref>Instituut-Lorentz, Einstein archive at the Instituut-Lorentz, 2005.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Subatomic particles divide into two classes: the [[boson]]s which obey Bose-Einstein probability statistics, and the [[fermion]]s which do not, they obey Fermi-Dirac statistics. Neither is like familiar classical probability statistics. To give a sense of the difference, two classical coins have a 50-50 probability of coming up a pair (two heads or two tails), two boson coins have exactly 100 percent probability of coming up a pair, while two fermion coins have exactly zero probability of coming up a pair. | |

| − | + | ===Schrödinger gas model=== | |

| − | + | Einstein suggested to [[Erwin Schrödinger]] an application of [[Max Planck]]'s idea of treating [[energy level]]s for a [[gas]] as a whole rather than for individual [[molecule]]s, and Schrödinger applied this in a paper using the [[Boltzmann distribution]] to derive the [[thermodynamics|thermodynamic]] properties of a [[semiclassical]] [[ideal gas]]. Schrödinger urged Einstein to add his name as co-author, although Einstein declined the invitation.<ref>Walter Moore, ''Schrödinger: Life and Thought.'' (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1989, ISBN 0521437679).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===The Einstein refrigerator=== | |

| + | In 1926, Einstein and his former student [[Leó Szilárd]], a Hungarian physicist who later worked on the [[Manhattan Project]] and is credited with the discovery of the [[chain reaction]], co-invented (and in 1930, patented) the [[Einstein refrigerator]], revolutionary for having no moving parts and using only heat, not ice, as an input.<ref>Gary Goettling, "Einstein's Refrigerator," ''Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine'' Online, Georgia Tech Alumni Association, 1998. </ref> | ||

| − | === | + | ===Bohr versus Einstein=== |

| − | + | [[Image:Niels Bohr Albert Einstein by Ehrenfest.jpg|left|thumb|200px|Einstein and [[Niels Bohr]]. Photo taken by [[Paul Ehrenfest]] during their visit to Leiden in December 1925.]] | |

| − | [[Image:Niels Bohr Albert Einstein by Ehrenfest.jpg| | ||

| − | In | + | In the 1920s, [[quantum mechanics]] developed into a more complete theory. Einstein was unhappy with the "[[Copenhagen interpretation]]" of quantum theory developed by [[Niels Bohr]] and [[Werner Heisenberg]], wherein quantum phenomena are inherently probabilistic, with definite states resulting only upon interaction with [[Physics in the Classical Limit|classical systems]]. A public [[Einstein-Bohr debates|debate]] between Einstein and Bohr followed, lasting for many years (including during the [[Solvay Conference]]s). Einstein formulated [[thought experiment|gedanken experiments]] against the Copenhagen interpretation, which were all rebutted by Bohr. In a 1926 letter to [[Max Born]], Einstein wrote: "I, at any rate, am convinced that He does not throw dice."<ref>Albert Einstein. ''Albert Einstein, Hedwig und Max Born: Briefwechsel 1916–1955.'' (Munich, DE: Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung, 1969).</ref> |

| − | + | Einstein was never satisfied by what he perceived to be quantum theory's intrinsically incomplete description of nature, and in 1935 he further explored the issue in collaboration with [[Boris Podolsky]] and [[Nathan Rosen]], noting that the theory seems to require [[non-local]] interactions; this is known as the [[EPR paradox]]. The EPR gedanken experiment has since been performed, with results confirming quantum theory's predictions.<ref>Alain Aspect, Jean Dalibard, Gérard Roger, Experimental test of Bell's inequalities using time-varying analyzers. ''Physical Review Letters'' 49(25) (1982):1804-1807.</ref> | |

| − | + | Einstein's disagreement with Bohr revolved around the idea of scientific [[determinism]]. For this reason the repercussions of the [[Einstein-Bohr debates|Einstein-Bohr debate]] have found their way into philosophical discourse as well. | |

| − | < | + | ==Religious views== |

| + | The question of scientific determinism gave rise to questions about Einstein's position on [[theological determinism]], and even whether or not he believed in God. In 1929, Einstein told Rabbi [[Herbert S. Goldstein]] "I believe in [[Baruch Spinoza#Overview of his philosophy|Spinoza's God]], who reveals Himself in the lawful harmony of the world, not in a God Who concerns Himself with the fate and the doings of mankind."<ref>Dennis Brian, ''Einstein: A Life.'' (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 1996, ISBN 0471114596).</ref> In 1950, in a letter to M. Berkowitz, Einstein stated that "My position concerning God is that of an agnostic. I am convinced that a vivid consciousness of the primary importance of moral principles for the betterment and ennoblement of life does not need the idea of a law-giver, especially a law-giver who works on the basis of reward and punishment."<ref>Alice Calaprice, (ed.) ''The Expanded Quotable Einstein.'' (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000, ISBN 0691120749).</ref> | ||

| − | + | Einstein defined his religious views in a letter he wrote in response to those who claimed that he worshipped a Judeo-Christian god: "It was, of course, a lie what you read about my religious convictions, a lie which is being systematically repeated. I do not believe in a personal God and I have never denied this but have expressed it clearly. If something is in me which can be called religious then it is the unbounded admiration for the structure of the world so far as our science can reveal it."<ref>Helen Dukas and Banesh Hoffman, (eds.) ''Albert Einstein, The Human Side.'' (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981 ISBN 0691082316).</ref> | |

| − | + | By his own definition, Einstein was a deeply religious person.<ref>Abraham Pais, ''Subtle is the Lord. The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein.'' (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1982, ISBN 0195204387).</ref> He published a paper in ''[[Nature (journal)|Nature]]'' in 1940 entitled "Science and Religion" which gave his views on the subject.<ref name="Nature146">Albert Einstein, "Science and Religion." ''Nature'' 146 (1940):605–607.</ref> In this he says that: "a person who is religiously enlightened appears to me to be one who has, to the best of his ability, liberated himself from the fetters of his selfish desires and is preoccupied with thoughts, feelings and aspirations to which he clings because of their super-personal value … regardless of whether any attempt is made to unite this content with a Divine Being, for otherwise it would not be possible to count [[Buddha]] and [[Spinoza]] as religious personalities. Accordingly a religious person is devout in the sense that he has no doubt of the significance of those super-personal objects and goals which neither require nor are capable of rational foundation …. In this sense religion is the age-old endeavor of mankind to become clearly and completely conscious of these values and goals, and constantly to strengthen their effects." He argues that conflicts between science and religion "have all sprung from fatal errors." However "even though the realms of religion and science in themselves are clearly marked off from each other" there are "strong reciprocal relationships and dependencies" … "science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind … a legitimate conflict between science and religion cannot exist." However he makes it clear that he does not believe in a personal God, and suggests that "neither the rule of human nor Divine Will exists as an independent cause of natural events. To be sure, the doctrine of a personal God interfering with natural events could never be ''refuted'' … by science, for [it] can always take refuge in those domains in which scientific knowledge has not yet been able to set foot."<ref name="Nature146"/> | |

| − | |||

| − | < | + | Einstein championed the work of psychologist [[Paul Diel]],<ref>Hervé Toulhoat, Paul Diel, pionnier de la psychologie des profondeurs et Albert Einstein. ''Chimie Paris'' 315 (2006):12–15.</ref> which posited a biological and psychological, rather than theological or sociological, basis for morality.<ref>Paul Diel, ''The God-Symbol: Its History and its Significance.'' (San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row, 1986, ISBN 0062548050).</ref> |

| − | + | The most thorough exploration of Einstein's views on religion was made by his friend [[Max Jammer]] in the 1999 book ''Einstein and Religion.''<ref>Max Jammer, ''Einstein and Religion.'' (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999, ISBN 0691006997).</ref> | |

| − | + | Einstein was an Honorary Associate of the [[Rationalist Press Association]] beginning in 1934, and was an admirer of [[Ethical Culture]]. He served on the advisory board of the [[First Humanist Society of New York]]. | |

| − | + | ==Politics== | |

| − | + | With increasing public demands, his involvement in political, humanitarian and academic projects in various countries and his new acquaintances with scholars and political figures from around the world, Einstein was less able to get the productive isolation that, according to biographer [[Ronald W. Clark]], he needed in order to work.<ref>Ronald W. Clark, ''Einstein: The Life and Times'' (New York, NY: Avon Books, 1971, ISBN 0380441233).</ref> Due to his fame and genius, Einstein found himself called on to give conclusive judgments on matters that had nothing to do with theoretical physics or mathematics. He was not timid, and he was aware of the world around him, with no illusion that ignoring politics would make world events fade away. His very visible position allowed him to speak and write frankly, even provocatively, at a time when many people of conscience could only flee to the [[Resistance during World War II|underground]] or keep doubts about developments within their own movements to themselves for fear of internecine fighting. Einstein flouted the ascendant [[Nazi]] movement, tried to be a voice of moderation in the tumultuous formation of the [[State of Israel]] and braved anti-communist politics and resistance to the [[civil rights]] movement in the United States. He became honorary president of the [[League against Imperialism]] created in [[Brussels]] in 1927. | |

| − | In | + | ===Zionism=== |

| + | Einstein was a [[Cultural Zionism|cultural Zionist]]. In 1931, The Macmillan Company published ''About Zionism: Speeches and Lectures by Professor Albert Einstein.'' [[Querido]], an [[Amsterdam]] publishing house, collected 11 of Einstein's essays into a 1933 book entitled ''Mein Weltbild,'' translated to English as ''The World as I See It''; Einstein's foreword dedicates the collection "to the Jews of Germany." In the face of Germany's rising [[militarism]] Einstein wrote and spoke for peace.<ref>American Museum of Natural History, "Einstein's Revolution," 2002.</ref> | ||

| + | [[Image:Einsteinwiezmann.PNG|thumb|right|250px|Albert Einstein seen here with his second wife [[Elsa Einstein]] and Zionist leaders, including future President of Israel [[Chaim Weizmann]], his wife [[Vera Weizmann|Dr. Vera Weizmann]], [[Menachem Ussishkin]] and Ben-Zion Mossinson on arrival in New York City in 1921.]] | ||

| − | + | Despite his years as a proponent of Jewish history and culture, Einstein publicly stated reservations about the proposal to partition the British-supervised [[British Mandate of Palestine]] into independent Arab and Jewish countries. In a 1938 speech, "Our Debt to Zionism," he said: "I am afraid of the inner damage Judaism will sustain - especially from the development of a narrow nationalism within our own ranks, against which we have already had to fight strongly, even without a Jewish state."<ref>David E. Rowe & Robert Schulmann, ''Einstein on Politics: His Private Thoughts and Public Stands on Nationalism, Zionism, War, Peace, and the Bomb.'' (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007, ISBN 0691120943).</ref> The [[United Nations]] did divide the mandate, demarcating the borders of several new countries including the [[State of Israel]], and [[1948 Arab-Israeli War|war]] broke out immediately. Einstein was one of the authors of a 1948 letter to the [[New York Times]] criticizing [[Menachem Begin]]'s [[Revisionist Zionism|Revisionist]] [[Herut]] (Freedom) Party for the [[Deir Yassin massacre]].<ref>Albert Einstein et al., To the editors. ''The New York Times'', 1948. </ref> | |

| + | Einstein served on the Board of Governors of [[The Hebrew University|The Hebrew University of Jerusalem]]. In his Will of 1950, Einstein bequeathed literary rights to his writings to The Hebrew University, where many of his original documents are held in the Albert Einstein Archives.<ref>[http://www.alberteinstein.info/ Einstein Archives Online] Retrieved December 18, 2007.</ref> | ||

| − | Einstein | + | When President [[Chaim Weizmann]] died in 1952, Einstein was asked to be Israel's second president but he declined. He wrote: "I am deeply moved by the offer from our State of Israel, and at once saddened and ashamed that I cannot accept it."<ref>[http://www.princetonhistory.org/museum_alberteinstein.cfm Albert Einstein Museum.] ''Princeton History''. Retrieved December 18, 2007.</ref> |

| − | + | ===Nazism=== | |

| − | + | In January 1933, [[Adolf Hitler]] was elected [[Chancellor of Germany]]. One of the first actions of Hitler's administration was the "Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums" (the [[Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service]]) which removed Jews and politically suspect government employees (including university professors) from their jobs, unless they had demonstrated their loyalty to Germany by serving in World War I. In December 1932, in response to this growing threat, Einstein had prudently traveled to the USA. For several years he had been wintering at the [[California Institute of Technology]] in [[Pasadena, California]],<ref>R. Clark, ''Einstein: The Life and Times.'' (New York, NY: H.N. Abrams, 1984, ISBN 0810908751).</ref> and also was a guest lecturer at [[Abraham Flexner]]'s newly founded [[Institute for Advanced Study]] in [[Princeton, New Jersey|Princeton]], [[New Jersey]]. | |

| − | + | The Einstein family bought a house in Princeton (where Elsa died in 1936), and Einstein remained an integral contributor to the [[Institute for Advanced Study]] until his death in 1955. During the 1930s and into World War II, Einstein wrote [[affidavits]] recommending United States [[visa (document)|visas]] for a huge number of Jews from Europe trying to flee persecution, raised money for Zionist organizations and was in part responsible for the formation, in 1933, of the [[International Rescue Committee]].<ref>[http://www.theirc.org/ Official Website]. ''International Rescue Committee''. Retrieved December 17, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | Meanwhile in [[Germany]], a campaign to eliminate Einstein's work from the German lexicon as unacceptable "[[Jewish physics]]" ''(Jüdische physik)'' was led by Nobel laureates [[Philipp Lenard]] and [[Johannes Stark]]. ''[[Deutsche Physik]]'' activists published pamphlets and even textbooks denigrating Einstein, and instructors who taught his theories were [[blacklist]]ed, including Nobel laureate [[Werner Heisenberg]] who had debated quantum probability with Bohr and Einstein. Philipp Lenard claimed that the mass–energy equivalence formula needed to be credited to [[Friedrich Hasenöhrl]] to make it an [[Aryan race#Nazism|Aryan]] creation. | |

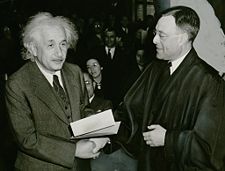

| − | + | Einstein became a citizen of the United States in 1940, although he retained his Swiss citizenship. | |

| − | + | [[Image:Citizen-Einstein.jpg|right|thumb|225px|Albert Einstein receiving his certificate of American citizenship from Judge [[Phillip Forman]].]] | |

| − | + | ===The atomic bomb=== | |

| + | Concerned scientists, many of them refugees from European anti-Semitism in the U.S., recognized the possibility that German scientists were working toward developing an atomic bomb. They knew that Einstein's fame might make their fears more believable. In 1939, Leo Szilárd and Einstein wrote a [[Einstein-Szilárd letter|letter]] to U.S. Pres. [[Franklin Delano Roosevelt]] warning that the [[Third Reich]] might be developing [[nuclear weapon]]s based on their own research. | ||

| − | + | The United States took stock of this warning, and within five years, the U.S. [[Manhattan Project|created its own nuclear weapons]], and used them to end the war with [[Japan]], dropping them on the Japanese cities of [[Nagasaki]] and [[Hiroshima]]. According to chemist and author [[Linus Pauling]], Einstein later expressed regret about the Szilárd-Einstein letter. | |

| − | + | Along with other prominent individuals such as [[Eleanor Roosevelt]] and [[Henry Morgenthau, Jr.]], Einstein in 1947 participated in a "National Conference on the German Problem," which produced a declaration stating that "any plans to resurrect the economic and political power of Germany… [were] dangerous to the security of the world."<ref>Steven Casey, The campaign to sell a harsh peace for Germany to the American public, 1944–1948. ''History'' 90(297) (2005):62–92.</ref> | |

| − | [[ | + | ===Cold War era=== |

| − | + | When he was a visible figure working against the rise of [[Nazism]], Einstein had sought help and developed working relationships in both the West and what was to become the [[Soviet bloc]]. After World War II, enmity between the former allies became a very serious issue for people with international resumes. To make things worse, during the first days of [[McCarthyism]] Einstein was writing about a single [[world government]]; it was at this time that he wrote, | |

| + | <blockquote>"I do not know how the third World War will be fought, but I can tell you what they will use in the Fourth—rocks!"<ref>Alice Calaprice, ''The New quotable Einstein.'' (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005, ISBN 0691120757).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | In a 1949 ''Monthly Review'' article entitled "Why Socialism?" Albert Einstein described a chaotic [[capitalism|capitalist]] society, a source of evil to be overcome, as the "predatory phase of human development".<ref>Albert Einstein, Why Socialism? ''Monthly Review'', 1949.</ref> With [[Albert Schweitzer]] and [[Bertrand Russell]], Einstein lobbied to stop nuclear testing and future bombs. Days before his death, Einstein signed the [[Russell-Einstein Manifesto]], which led to the [[Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs]]. | ||

| − | + | Einstein was a member of several [[American Civil Rights Movement|civil rights]] groups, including the Princeton chapter of the [[NAACP]]. When the aged [[W.E.B. DuBois]] was accused of being a communist spy, Einstein volunteered as a character witness and the case was dismissed shortly afterward. Einstein's friendship with activist [[Paul Robeson]], with whom he served as co-chair of the [[American Crusade Against Lynching|American Crusade to End Lynching]], lasted 20 years. | |

| − | + | In 1946, Einstein collaborated with [[Rabbi]] [[Israel Goldstein]], Middlesex heir [[C. Ruggles Smith]], and activist attorney [[George Alpert]] on the Albert Einstein Foundation for Higher Learning, Inc., which was formed to create a Jewish-sponsored secular university, open to all students, on the grounds of the former Middlesex College in Waltham, Massachusetts. Middlesex was chosen in part because it was accessible from both Boston and New York City, Jewish cultural centers of the USA. Their vision was a university "deeply conscious both of the Hebraic tradition of Torah looking upon culture as a birthright, and of the American ideal of an educated democracy."<ref name=Reis>Arthur H. Reis, Jr., The Albert Einstein Involvement. ''Brandeis Review, 50th Anniversary Edition'', 1998. </ref> The collaboration was stormy, however. Finally, when Einstein wanted to appoint British economist [[Harold J. Laski]] as the university's president, Alpert wrote that Laski was "a man utterly alien to American principles of democracy, tarred with the Communist brush."<ref name=Reis/> Einstein withdrew his support and barred the use of his name.<ref>Dr. Einstein Quits University Plan. ''The New York Times''.</ref> The university opened in 1948 as [[Brandeis University]]. In 1953, Brandeis offered Einstein an honorary degree, but he declined.<ref name=Reis/> | |

| − | + | Given Einstein's links to [[Germany]] and [[Zionism]], his [[Socialism|socialistic]] ideals, and his perceived links to Communist figures, the U.S. [[Federal Bureau of Investigation]] kept a file on Einstein that grew to 1,427 pages. Many of the documents in the file were sent to the FBI by concerned citizens, some objecting to his immigration while others asked the FBI to protect him.<ref>"Albert Einstein." FBI Freedom of Information Act Website. U.S. Federal Government, U.S. Department of Justice.</ref> | |

| − | + | Although Einstein had long been sympathetic to the notion of [[vegetarianism]], it was only near the start of 1954 that he adopted a strict vegetarian diet. | |

| − | + | ==Death== | |

| + | On April 17, 1955, Albert Einstein experienced internal bleeding caused by the rupture of an [[aortic aneurysm]]. He took a draft of a speech he was preparing for a television appearance commemorating the State of Israel's seventh anniversary with him to the hospital, but he did not live long enough to complete it.<ref>[http://www.alberteinstein.info/ Einstein Archives Online]. Retrieved December 18, 2007.</ref> He died in Princeton Hospital early the next morning at the age of 76. Einstein's remains were cremated and his ashes were scattered.<ref>J.J. O'Connor & E.F. Robertson, "Albert Einstein," The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St. Andrews, 1997.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Before the cremation, Princeton Hospital pathologist [[Thomas Stoltz Harvey]] removed [[Albert Einstein's brain|Einstein's brain]] for preservation, in hope that the [[neuroscience]] of the future would be able to discover what made Einstein so intelligent. | |

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| − | Einstein | + | While traveling, Einstein had written daily to his wife Elsa and adopted stepdaughters, Margot and Ilse, and the letters were included in the papers bequeathed to The Hebrew University. [[Margot Einstein]] permitted the personal letters to be made available to the public, but requested that it not be done until 20 years after her death (she died in 1986).<ref>[http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9A0DEFD9153FF931A25754C0A960948260 Obituary.] ''The New York Times''. Retrieved December 17, 2007.</ref> Barbara Wolff, of [[The Hebrew University]]'s Albert Einstein Archives, told the [[British Broadcasting Company|BBC]] that there are about 3500 pages of private correspondence written between 1912 and 1955.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/5168002.stm Letters reveal Einstein love life]. ''BBC News''. Retrieved December 18, 2007.</ref> |

| − | + | The United States' [[National Academy of Sciences]] commissioned the ''[[Albert Einstein Memorial]],'' a monumental bronze and marble sculpture by [[Robert Berks]], dedicated in 1979 at its Washington, D.C. campus adjacent to the [[National Mall]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Einstein bequeathed the [[royalties]] from use of his [[personality rights|image]] to [[The Hebrew University|The Hebrew University of Jerusalem]]. [[The Roger Richman Agency]] [[licence]]s the use of his name and associated imagery, as [[agent (law)|agent]] for the Hebrew University.<ref>[http://www.albert-einstein.net/index2.html Albert Einstein Licensing Program.] ''Albert Einstein.net''. Retrieved December 18, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | In | + | ==Honors== |

| + | {{readout||right|250px|Albert Einstein is considered the greatest scientist of the twentieth century and was named "Person of the Century" by TIME magazine}} | ||

| + | In 1999, Albert Einstein was named "[[Person of the Century]]" by ''[[Time (magazine)|TIME]]'' magazine,<ref>[http://www.time.com/time/time100/poc/magazine/albert_einstein5a.html Person of the Century: Albert Einstein.] ''TIME''. Retrieved December 18, 2007.</ref> the [[Gallup Poll]] recorded him as the fourth most [[Gallup's List of Widely Admired People|admired]] person of the twentieth century and according to "The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History," Einstein is "the greatest scientist of the twentieth century and one of the supreme intellects of all time."<ref>Hart 1978</ref> | ||

| − | + | A partial list of his memorials: | |

| + | *The [[International Union of Pure and Applied Physics]] named 2005 the "[[World Year of Physics]]" in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the publication of the ''Annus Mirabilis'' Papers. | ||

| + | * The ''[[Albert Einstein Memorial]]'' by [[Robert Berks]] | ||

| + | * A unit used in [[photochemistry]], the ''[[einstein (unit)|einstein]]'' | ||

| + | * The [[chemical element]] 99, [[einsteinium]] | ||

| + | * The [[asteroid]] [[2001 Einstein]] | ||

| + | * The [[Albert Einstein Award]] | ||

| + | * The [[Albert Einstein Peace Prize]] | ||

| − | + | ==Major works== | |

| − | + | *Einstein, Albert. Folgerungen aus den Capillaritätserscheinungen (Conclusions Drawn from the Phenomena of Capillarity). ''Annalen der Physik'' 4 (1901):513. | |

| − | + | *Einstein, Albert. On a Heuristic Viewpoint Concerning the Production and Transformation of Light. ''Annalen der Physik'' 17 (1905):132–148. | |

| + | *Einstein, Albert. A new determination of molecular dimensions. This Ph.D. thesis was completed April 30 and submitted July 20, 1905. | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert. On the Motion—Required by the Molecular Kinetic Theory of Heat—of Small Particles Suspended in a Stationary Liquid. ''Annalen der Physik'' 17 (1905):549–560. | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert. On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies. ''Annalen der Physik'' 17 (1905):891–921. | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert. Does the Inertia of a Body Depend Upon Its Energy Content? ''Annalen der Physik'' 18 (1905):639–641. | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert. Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation (The Field Equations of Gravitation). ''Koniglich Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften'' (1915): 844–847. | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert. Kosmologische Betrachtungen zur allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie (Cosmological Considerations in the General Theory of Relativity). ''Koniglich Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften'' (1917). | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert. Zur Quantentheorie der Strahlung (On the Quantum Mechanics of Radiation). ''Physikalische Zeitschrift'' 18 (1917):121–128. | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert. Fundamental Ideas and Problems of the Theory of Relativity. ''Nobel Lectures, Physics 1901–1921'', 1923. | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert. Quantentheorie des einatomigen idealen Gases (Quantum theory of monatomic ideal gases). ''Sitzungsberichte der Preussichen Akademie der Wissenschaften Physikalisch—Mathematische Klasse'' (1924): 261–267. | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert. Die Ursache der Mäanderbildung der Flussläufe und des sogenannten Baerschen Gesetzes. ''Die Naturwissenschaften'' (1926): 223-224. | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert, Boris Podolsky, Nathan Rosen. Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete? ''Physical Review'' 47(10) (1935):777–780. | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert. On Science and Religion. ''Nature'' 146 (1940). | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert, et al. [http://phys4.harvard.edu/~wilson/NYTimes1948.html To the editors]. ''The New York Times'', 1948. Retrieved December 18, 2007. | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert. [http://www.monthlyreview.org/598einst.htm Why Socialism?]. ''Monthly Review'', 1949. Retrieved December 18, 2007. | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert. On the Generalized Theory of Gravitation. ''Scientific American'' CLXXXII(4) (1950):13–17. | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert. ''Ideas and Opinions.'' New York, NY: Random House, 1954. ISBN 0517003937. | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert. ''Albert Einstein, Hedwig und Max Born: Briefwechsel 1916–1955.'' Munich, DE: Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung, 1969. | ||

| + | *Einstein, Albert, Paul Arthur Schilpp, trans. ''Autobiographical Notes.'' Chicago, IL: Open Court, 1979. ISBN 0875483526. | ||

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| − | + | {{Reflist|2}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==References== | |

| + | * Beck, Anna. ''The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 1: The Early Years, 1879–1902. (English translation supplement).'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0691084756. | ||

| + | * Bodanis, David. [http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/einstein/ Einstein's Big Idea]. ''Public Broadcasting Service'', 2005. Retrieved December 18, 2007. | ||

| + | * Bolles, Edmund Blair. ''Einstein Defiant: Genius versus Genius in the Quantum Revolution.'' Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press, 2004. ISBN 0309089980. | ||

| + | * Brian, Dennis. ''Einstein: A Life.'' Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 1996. ISBN 0471114596. | ||

| + | * Butcher, Sandra Ionno. [http://www.pugwash.org/publication/phs/history9.pdf The Origins of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto]. ''Pugwash History Series'', 2005. Retrieved December 18, 2007. | ||

| + | * Calaprice, Alice. ''The New quotable Einstein.'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005. ISBN 0691120757. | ||

| + | * Clark, Ronald W. ''Einstein: The Life and Times.'' New York, NY: Avon, 1971. ISBN 0380441233. | ||

| + | * Crelinsten, Jeffrey. ''Einstein's Jury: The Race to Test Relativity.'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0691123103. | ||

| + | * Ericson, Edward L. [http://www.aeu.org/ericson2.html The Humanist Way: An Introduction to Ethical Humanist Religion]. ''American Ethical Union'', 2006. Retrieved December 18, 2007. | ||

| + | * Esterson, Allen. [http://www.esterson.org/milevamaric.htm Mileva Marić: Einstein's Wife]. ''Esterson.org''. Retrieved December 18, 2007. | ||

| + | * Galison. Peter. Einstein's Clocks: The Question of Time. ''Critical Inquiry''. 26(2) (2000):355–389. | ||

| + | * Goettling, Gary. [http://gtalumni.org/StayInformed/magazine/sum98/einsrefr.html Einstein's Refrigerator]. ''Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine'' Online, 1998. Retrieved December 18, 2007. | ||

| + | * Golden, Frederic. [http://www.time.com/time/time100/poc/magazine/albert_einstein5a.html Person of the Century: Albert Einstein]. ''TIME'', 2000. Retrieved December 18, 2007. | ||

| + | * Hart, Michael H. ''The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History.'' New York, NY: Hart Pub. Co., 1978. ISBN 0806513500. | ||

| + | * Hentschel, Klaus, Ann M. Hentschel. ''Physics and National Socialism: An Anthology of Primary Sources.'' Boston, MA: Birkhaeuser Verlag, 1996. ISBN 3764353120. | ||

| + | * Herschbach, Dudley. [http://www.chem.harvard.edu/herschbach/Einstein_Student.pdf Einstein as a Student]. ''Harvard Chemistry Dept.,'' 2005. Retrieved December 18, 2007. | ||

| + | * Highfield, Roger, and Paul Carter. ''The Private Lives of Albert Einstein.'' Boston, MA: Faber and Faber, 1993. ISBN 0312110472. | ||

| + | * Holt, Jim. [http://web.archive.org/web/20060218113744/http://www.newyorker.com/critics/atlarge/?050228crat_atlarge Time Bandits]. ''The New Yorker'', 2005. Retrieved December 21, 2007. | ||

| + | * Isaacson, Walter. ''Einstein: His Life and Universe.'' New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2007. ISBN 978-0743264730. | ||

| + | * Isaacson, Walter. [http://www.time.com/time/time100/poc/magazine/who_mattered_and_why4a.html Person of the Century: Why We Chose Einstein.] ''TIME'', 2000. Retrieved December 21, 2007. | ||

| + | * Jammer, Max. ''Einstein and Religion.'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 0691006997. | ||

| + | * Kant, Horst, and Jürgen Renn, (eds.). ''Albert Einstein - Chief Engineer of the Universe: One Hundred Authors for Einstein.'' Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-VCH, 2005. ISBN 3527405747. | ||

| + | * Kupper, Hans-Josef. [http://www.einstein-website.de/z_information/variousthings.html Various things about Albert Einstein.] ''Einstein Website'', 2000. Retrieved December 21, 2007. | ||

| + | * Levenson, Thomas. [http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/einstein/genius/ "Genius Among Geniuses"] : Einstein's Big Idea. Public Broadcasting Service, 2005. Retrieved December 21, 2007. | ||

| + | * Levitt, Dan. ''Brilliant Minds: Secrets of the Cosmos''. Boston, MA: Veriscope Pictures, 2003. | ||

| + | * Martínez, Alberto A. [http://physicsweb.org/articles/world/17/4/2 Arguing about Einstein's wife]. ''Physics World'', 2004. Retrieved December 21, 2007. | ||

| + | * Mehra, Jagdish. ''The Golden Age of Theoretical Physics.'' River Edge, NJ: World Scientific, 2001. ISBN 978-9810243425. | ||

| + | * Pais, Abraham. ''Subtle is the Lord. The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein.'' Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1982. ISBN 0195204387. | ||

| + | * Pais, Abraham. ''Einstein Lived Here.'' Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 0198539940. | ||

| + | * Pickover, Clifford A. ''Sex, Drugs, Einstein, and Elves: Sushi, Psychedelics, Parallel Universes, and the Quest for Transcendence.'' Petaluma, CA: Smart Publications, 2005. ISBN 1890572179. | ||

| + | * Renn, Jürgen. ''Albert Einstein - Chief Engineer of the Universe: One Hundred Authors for Einstein.'' Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-VCH, 2005. ISBN 3527405747. | ||

| + | * Renn, Jürgen. ''Albert Einstein - Chief Engineer of the Universe: Einstein's Life and Work in Context and Documents of a Life's Pathway.'' Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-VCH, 2006. ISBN 3527405712. | ||

| + | * Robinson, Andrew. ''Einstein: A Hundred Years of Relativity.'' New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, 2005. ISBN 0954510348. | ||

| + | * Rosenkranz, Ze'ev. ''Albert Einstein—Derrière l'image.'' Zurich: Editions NZZ, 2005. ISBN 3038231827. | ||

| + | * Rowe, David E., Robert Schulmann. ''Einstein on Politics: His Private Thoughts and Public Stands on Nationalism, Zionism, War, Peace, and the Bomb.'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007. ISBN 0691120943. | ||

| + | * Smith, Peter D. ''Einstein (Life & Times Series).'' London, UK: Haus Publishing, 2000. ISBN 1904341152. | ||

| + | * Sowell, Thomas. ''The Einstein Syndrome: Bright Children Who Talk Late.'' New York, NY: Basic Books, 2001. ISBN 0465081401. | ||

| + | * Stachel, John, H.M. Pycior, N.G. Slack, P.G. Abir-Am (eds.). "Albert Einstein and Mileva Maric: A Collaboration That Failed to Develop." ''Creative Couples in the Sciences.'' New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996. ISBN 0813521882. | ||

| + | * Stachel, John. ''Einstein's Miraculous Year: Five Papers That Changed the Face of Physics.'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998. ISBN 0691059381. | ||

| + | *Stachel, John, Martin J. Klein, A. J. Kox, Michel Janssen, R. Schulmann, Diana Komos Buchwald and others, (eds.). ''The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Vol 1–10.'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987–2006. | ||

| + | * Stern, Fritz. ''Einstein's German World.'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 069105939X. | ||

| + | * Thorne, Kip. ''Black Holes and Time Warps|Black Holes and Time Warps: Einstein's Outrageous Legacy.'' New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1995. ISBN 0393312763. | ||

| + | * Zackheim, Michele. ''Einstein's Daughter: the Search for Lieserl.'' New York, NY: Riverhead Books, 1999. ISBN 1573221279. | ||

| − | + | ==External links== | |

| + | All links retrieved June 17, 2023. | ||

| − | + | * [http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/einstein/rela-i.html Einstein Thought Experiments] | |

| − | + | * {{gutenberg author| id=Albert+Einstein | name=Albert Einstein}} (complete texts, downloadable, no charge). | |

| − | + | * [http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Einstein.html "The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive": Albert Einstein] University of Saint Andrews, School of Mathematics and Statistics. | |

| − | + | * [http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/einstein/ "Einstein's Big Idea"] NOVA television documentary series website, Public Broadcasting Service (can watch a preview online). | |

| − | + | * [http://www.einstein.caltech.edu/index.html Einstein Papers Project]. ''Caltech''. | |

| − | + | * [http://www.idsia.ch/~juergen/einstein.html Albert Einstein (1879–1955) and the "Greatest Scientific Discovery Ever"] | |

| − | + | * [http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1921/einstein-bio.html Albert Einstein - Biography]. ''Nobel Lectures, Physics 1901–1921''. | |

| − | + | * [http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1921/ The Nobel Prize in Physics 1921]. ''Nobel Foundation''. | |

| − | + | * [http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F50812FA385D13728DDDAB0A94DE405B8788F1D3 Dr. Einstein Quits University Plan]. ''The New York Times''. | |

| − | + | * [http://www.lorentz.leidenuniv.nl/history/Einstein_archive/ Einstein archive at the Instituut-Lorentz.] ''Instituut-Lorentz''. | |

| − | + | * [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/5168002.stm Letters Reveal Einstein Love Life]. ''BBC News''. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{academia | {{academia | ||

| Line 413: | Line 308: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {{Nobel Prize in Physics | + | {{Nobel Prize in Physics Laureates 1901-1925}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | }} | ||

[[Category:Physical sciences]] | [[Category:Physical sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Biography]] | [[Category:Biography]] | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Physicists]] |

| − | {{credit| | + | {{credit|155975215}} |

Latest revision as of 05:00, 17 June 2023

|

Albert Einstein | |

|---|---|

Photographed by Oren J. Turner (1947) | |

| Born |

March 14 1879 |

| Died | April 18 1955 (aged 76) Princeton, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Residence | |

| Nationality | |

| Ethnicity | Jewish |

| Field | Physics |

| Institutions | Swiss Patent Office (Berne) Univ. of Zürich Charles Univ. Prussian Acad. of Sciences Kaiser Wilhelm Inst. Univ. of Leiden Inst. for Advanced Study |

| Alma mater | ETH Zürich |

| Academic advisor | Alfred Kleiner |

| Known for | General relativity Special relativity Brownian motion Photoelectric effect Mass-energy equivalence Einstein field equations Unified Field Theory Bose–Einstein statistics EPR paradox |

| Notable prizes | Copley Medal (1925) Max Planck medal (1929) |

Albert Einstein (March 14, 1879 – April 18, 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist. He is best known for his theory of relativity and specifically the equation , which indicates the relationship between mass and energy (or mass-energy equivalence). Einstein received the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics "for his services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect."

Einstein's many contributions to physics include his special theory of relativity, which reconciled mechanics with electromagnetism, and his general theory of relativity which extended the principle of relativity to non-uniform motion, creating a new theory of gravitation. His other contributions include relativistic cosmology, capillary action, critical opalescence, classical problems of statistical mechanics and their application to quantum theory, an explanation of the Brownian movement of molecules, atomic transition probabilities, the quantum theory of a monatomic gas, thermal properties of light with low radiation density (which laid the foundation for the photon theory), a theory of radiation including stimulated emission, the conception of a unified field theory, and the geometrization of physics.

Works by Albert Einstein include more than 50 scientific papers and also non-scientific books. In 1999 Einstein was named TIME magazine's "Person of the Century," and a poll of prominent physicists named him the greatest physicist of all time. In popular culture, the name "Einstein" has become synonymous with genius.

Youth and schooling

Albert Einstein was born into a Jewish family in Ulm, Württemberg, Germany. His father was Hermann Einstein, a salesman and engineer. His mother was Pauline Einstein (née Koch). Although Albert had early speech difficulties, he was a top student in elementary school.[1]

In 1880, the family moved to Munich, where his father and his uncle founded a company, Elektrotechnische Fabrik J. Einstein & Cie that manufactured electrical equipment, providing the first lighting for the Oktoberfest and cabling for the Munich suburb of Schwabing. The Einsteins were not observant of Jewish religious practices, and Albert attended a Catholic elementary school. At his mother's insistence, he took violin lessons, and although he disliked them and eventually quit, he would later take great pleasure in Mozart's violin sonatas.

When Albert was five, his father showed him a pocket compass. Albert realized that something in empty space was moving the needle and later stated that this experience made "a deep and lasting impression".[2] As he grew, Albert built models and mechanical devices for fun, and began to show a talent for mathematics.

In 1889, family friend Max Talmud (later: Talmey), a medical student,[3] introduced the ten-year-old Albert to key science and philosophy texts, including Kant's Critique of Pure Reason and Euclid's Elements (Einstein called it the "holy little geometry book").[3] From Euclid, Albert began to understand deductive reasoning (integral to theoretical physics), and by the age of 12, he learned Euclidean geometry from a school booklet. Soon thereafter he began to investigate calculus.

In his early teens, Albert attended the new and progressive Luitpold Gymnasium. His father intended for him to pursue electrical engineering, but Albert clashed with authorities and resented the school regimen. He later wrote that the spirit of learning and creative thought were lost in strict rote learning.

In 1894, when Einstein was 15, his father's business failed, and the Einstein family moved to Italy, first to Milan and then, after a few months, to Pavia. During this time, Albert wrote his first scientific work, "The Investigation of the State of Aether in Magnetic Fields." Albert had been left behind in Munich to finish high school, but in the spring of 1895, he withdrew to join his family in Pavia, convincing the school to let him go by using a doctor's note.

Rather than completing high school, Albert decided to apply directly to the ETH Zürich, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Switzerland. Without a school certificate, he was required to take an entrance examination. He did not pass. Einstein wrote that it was in that same year, at age 16, that he first performed his famous thought experiment, visualizing traveling alongside a beam of light.[4]

The Einsteins sent Albert to Aarau, Switzerland to finish secondary school. While lodging with the family of Professor Jost Winteler, he fell in love with the family's daughter, Sofia Marie-Jeanne Amanda Winteler, called "Marie." (Albert's sister, Maja, his confidant, later married Paul Winteler.) In Aarau, Albert studied Maxwell's electromagnetic theory. In 1896, he graduated at age 17, renounced his German citizenship to avoid military service (with his father's approval), and finally enrolled in the mathematics program at ETH. On February 21, 1901, he gained Swiss citizenship, which he never revoked. Marie moved to Olsberg, Switzerland for a teaching post.

In 1896, Einstein's future wife, Mileva Marić, also enrolled at ETH, as the only woman studying mathematics. During the next few years, Einstein and Marić's friendship developed into romance. Einstein's mother objected because she thought Marić "too old," not Jewish, and "physically defective." This conclusion is from Einstein's correspondence with Marić. Lieserl is first mentioned in a letter from Einstein to Marić (who was abroad at the time of Lieserl's birth) dated February 4, 1902, from Novi Sad, Hungary.[5][6] Her fate is unknown.

Einstein graduated in 1900 from ETH with a degree in physics. That same year, Einstein's friend Michele Besso introduced him to the work of Ernst Mach. The next year, Einstein published a paper in the prestigious Annalen der Physik on the capillary forces of a straw.[7]

The Patent Office

Following graduation, Einstein could not find a teaching post. After almost two years of searching, a former classmate's father helped him get a job in Bern, at the Federal Office for Intellectual Property, the patent office, as an assistant examiner. His responsibility was evaluating patent applications for electromagnetic devices. In 1903, Einstein's position at the Swiss Patent Office was made permanent, although he was passed over for promotion until he "fully mastered machine technology".[8]