Albert Abraham Michelson

|

Albert Abraham Michelson | |

|---|---|

Albert Abraham Michelson | |

| Born |

December 19 1852 |

| Died | May 9 1931 (aged 78) Pasadena, California |

| Residence | |

| Nationality | |

| Ethnicity | Jewish-Polish |

| Field | Physicist |

| Institutions | Case Western Reserve University Clark University University of Chicago |

| Alma mater | US Naval Academy University of Berlin |

| Academic advisor | Hermann Helmholtz |

| Notable students | Robert Millikan |

| Known for | Speed of light Michelson-Morley experiment |

| Notable prizes | |

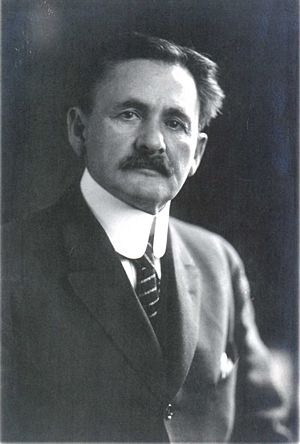

Albert Abraham Michelson (surname pronunciation anglicised as "Michael-son") (December 19, 1852 – May 9, 1931) was a Prussian-born American physicist. He is best remembered for his work on the measurement of the speed of light, particularly through his collaboration with Edward Morley in performing what has become known as the Michelson-Morley experiment. In 1907, he received the Nobel Prize in Physics, becoming the first American to receive a Nobel Prize in the sciences.

Life

Michelson, the son of a Jewish merchant, was born in what is today Strzelno, Poland (then Strelno, Provinz Posen in the Prussian-occupied region of partitioned Poland). He moved to the United States with his parents in 1855, when he was two years old, and grew up in the rough mining towns of Murphy's Camp, California, and Virginia City, Nevada, where his father sold goods to the gold miners. It was not until age 12 that he began formal schooling at San Francisco's Boys High School, whose principal, Theodore Bradley, is said to have exerted a strong influence on Michelson in terms of the young man's interest in science.

Michelson graduated from high school in 1869, and applied for admission to the U.S. Naval Academy. He was at first turned down, but he traveled to Washington and made a direct appeal to President Ulysses S. Grant, whose intervention made it possible for Michelson to be admitted to the academy.

During his four years as a midshipman at the Academy, Michelson excelled in optics, heat, and climatology as well as drawing. He was described by a fellow officer as "a real genius" and studied "less than any other man in the class and to occupy most of his time in scientific experiments, but he always stood near the head of his class." This did not preclude other activities, such as fencing and boxing (Fiske 1919, 15). After his graduation in 1873, and two years at sea, he returned to the Academy in 1875, to become an instructor in physics and chemistry until 1879.

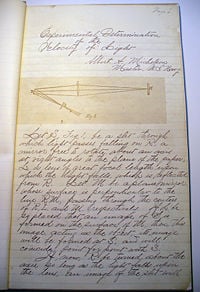

Michelson was fascinated with the sciences and the problem of measuring the speed of light in particular. While at Annapolis, he conducted his first experiments on the speed of light, as part of a class demonstration in 1877, using an apparatus that was an improvement upon that used by Léon Foucault in the mid-1800s for the same purpose. He conducted some preliminary measurements using largely improvised equipment in 1878, about which time his work came to the attention of Simon Newcomb, director of the Nautical Almanac Office who was already advanced in planning his own study. Michelson published his result of 299,910 kilometers per second (186,508 miles per hour) in 1878, before joining Newcomb in Washington DC to assist with his measurements there. Thus began a long professional collaboration and friendship between the two.

Newcomb, with his more adequately funded project, obtained a value of 299,860 kilometers per second in 1879, just at the extreme edge of consistency with Michelson's. Michelson continued to "refine" his method and in 1883, published a measurement of 299,853 kilometers per second, rather closer to that of his mentor.

Study abroad

Michelson obtained funding to continue his work from his brother-in-law, Albert Heminway, an investment banker (Hamerla 2006, 133). From 1880 to 1882, Michelson undertook postgraduate study at Berlin under Hermann Helmholtz and at Paris. He resigned from the navy in 1881, in order to more fully dedicate his energies to research.

It was Helmholtz who directed Michelson's attention to the problem of determining the earth's motion through the hypothetical ether that was believed to be the medium that transmitted light waves. James Clerk Maxwell and others had postulated such a medium, but Maxwell's equations seemed more dependent on such an idea than other formulations of electromagnetism. Helmholtz wanted to establish experimental evidence for Maxwell's view. With this object in mind, he had also put Heinrich Hertz on the trail of establishing the existence of electromagnetic waves.

The Michelson interferometer

Michelson won additional funding for his experiments from an institute established by Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone. Unable to carry out his delicate experiments in Berlin, he was given space at an observatory in Potsdam, where he continued his work.

Michelson's apparatus, which soon became known as the Michelson interferometer, diverted parts of the same light beam in different directions and then reflected them back to the same eyepiece. If the Earth moved through the ether that carried light waves, there would be a measurable difference in the time the two beams took to reach the eyepiece. This would become evident if a visible fringe developed when waves from one beam no longer coincided exactly with the other because of the delay.

Michelson found that no such fringes were produced, the conclusion being that the ether was carried along with the earth, thus masking the earth's motion through it, or that there simply was no ether. The latter possibility was not countenanced until Albert Einstein proposed it in 1905.

In 1881, Michelson left Berlin for Heidelberg, and then, Paris, where he came into contact with Robert Bunsen and others whose interests dovetailed with his own. He returned to the United States in 1882, and, through the agency of Newcomb, secured a professorship at Case Institute of Technology in Cleveland the following year.

Michelson and Morley

In 1884, Michelson met Edward Morley at a scientific conference in Montreal, and upon their return to the United States, discussed collaborative efforts to improve on Michelson's ether drift measurements. These plans did not bare immediate fruit, however, as Michelson's zealous dedication to his research made it appear that he was losing his mind. His wife referred him to a mental health specialist in New York, who recommended relaxation and freedom of movement, a prescription under which Michelson quickly progressed. By December of 1885, he had returned to Case.

In 1886, a fire at Case prevented Michelson from continuing his research there, but Morley provided space in his own laboratory where the two continued their work. After additional funds were raised with the help of Lord Rayleigh, the two men were able to construct a new interferometer by the beginning of 1887. From April to July of that same year, they conducted more accurate observations through their new apparatus than was possible with the equipment Michelson had used in Potsdam. The results were published soon after, and were considered conclusive by the scientific community, although both Morley and Michelson would continue to refine the experiment in later years.

Light and the standard of measurement

Around this time, Michelson developed procedures for using the wavelength of light as a standard of measure. The unit had at that time been defined as the distance between two notches in a metal bar. Michelson developed an apparatus for comparing the wavelength of particular spectral lines for sodium or cadmium with the distance between two metal plates. This type of standard for length was finally adopted in 1960, with the spectral lines of Krypton used for the purpose (Michelson 1903, 84-106). The standard was again changed in 1983, to the distance light travels in a small, fixed interval of time, the time itself becoming the fundamental standard.

In 1889, Michelson became a professor at Clark University at Worcester, Massachusetts and in 1892, was appointed professor and the first head of the department of physics at the newly organized University of Chicago.

In 1899, he married Edna Stanton, and the couple raised one son and three daughters.

In 1907, Michelson had the honor of being the first American to receive a Nobel Prize in Physics "for his optical precision instruments and the spectroscopic and metrological investigations carried out with their aid." He also won the Copley Medal in 1907, the Henry Draper Medal in 1916 and the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1923.

Astronomical interferometry

In 1920-21, Michelson and Francis G. Pease famously became the first people to measure the diameter of a star other than our Sun. While the method they used had been suggested by others, the telescopes before that time were not powerful enough to make the measurements. Michelson and Pease used an astronomical interferometer at the Mount Wilson Observatory to measure the diameter of the super-giant star Betelgeuse. A periscope arrangement was used to obtain a more intense image in the interferometer. The measurement of stellar diameters and the separations of binary stars took up an increasing amount of Michelson's life after this.

In 1930, Michelson, once again in collaboration with Pease, but also joined by Fred Pearson, used a new apparatus to obtain more accurate results in measuring the speed of light. Michelson did not live long enough to see the results of this experiment. The measurements were completed by his research partners, who calculated a speed of 299,774 kilometers per second in 1935, consistent with the prevailing values calculated by other means.

Michelson died in Pasadena, California, at the age of 78.

Legacy

Michelson was obsessed with the speed of light, but his life's work is also a testimony to Helmholtz, his mentor, who directed his path to one of the interesting topics of his time. If Helmholtz had not done so, Michelson's name would probably be no more than a footnote in the minutae of scientific development. Helmholtz deserves indirect credit for many of the discoveries of his students by likewise setting them on an investigational direction.

However, there can be little doubt that there were few people as qualified at the time as Michelson to perform ether drift measurements. Michelson's measurements of the speed of light had already become internationally known by the time he met Helmholtz in Berlin. Every high school student who has studied physics knows the names of Michelson and Morley, and this is a testimony to the originality of both investigators. Morley, who helped Michelson in his second series of measurements, was also involved in determining the atomic weight of oxygen. Michelson's life demonstrates not only the importance of personal initiative, but also the value of collaboration and team work.

Awards and honors

- Royal Society

- National Academy of Sciences

- American Physical Society

- American Association for the Advancement of Science

- Nobel Prize for Physics (1907)

- Rumford Prize (1888)

- Matteucci Medal (1903)

- Copley Medal (1907)

- Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1923)

- The Computer Measurement Group gives an annual A. A. Michelson award

- The University of Chicago Residence Halls remembered Michelson and his achievements by dedicating Michelson House in his honor.

- Case Western Reserve has also dedicated a Michelson House to him, and an academic building at the United States Naval Academy also bears his name. Michelson Laboratory at Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake in Ridgecrest, California is named after him. There is an interesting display in the publicly accessible area of the Lab of Michelson's Nobel Prize medal, the actual prize document, and examples of his diffraction gratings.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fiske, Bradley A. 1919. From Midshipman to Rear-Admiral. New York: Century Co. ISBN 0548176485

- Hamerla, R. R. 2006. An American Scientist on the Research Frontier: Edward Morley, Community, and Radical Ideas in Nineteenth-Century Science. Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 1402040881

- Livingston, D. M. The Master of Light: A Biography of Albert A. Michelson. ISBN 0-226-48711-3

- Michelson, Albert Abraham. 1903. Light Waves and Their Uses. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.