| Zürich | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

| Population | 371,767 (March 2007) | |||||||||

| - Density | 4,046 /km² (10,480 /sq.mi.) | |||||||||

| Area | 91.88 km² (35.5 sq mi) | |||||||||

| Elevation | 408 m (1,339 ft) | |||||||||

| Postal code | 8000-8099 | |||||||||

| Mayor (list) | Elmar Ledergerber | |||||||||

| Surrounded by (view map) |

Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon | |||||||||

| Twin towns | Kunming (PRC), San Francisco (United States) | |||||||||

| Website | www.stadt-zuerich.ch | |||||||||

Zürich ([ˈtsyːʁɪç], Zürich German: Züri [ˈtsyɾi], French: Zurich [zyʁiʃ], in English generally Zurich, Italian: Zurigo [dzu'ɾiːgo]) is the largest city in Switzerland (population: 371,767 in 2007; population of urban area is some 1,007,972) and capital of the canton of Zürich. The city is Switzerland's main commercial and cultural center (the political capital of Switzerland is Bern), and is widely considered to be one of the world's global cities. Surveys in 2006[1] and 2007[2], named Zurich the city with the best quality of life in the world.

Zurich grew into a town from an ancient Roman settlement. The grandson of Charlemagne, Louis the German, built a Carolingian castle on the site of the Roman castle, and in 835 founded the Fraumünster abbey for his daughter Hildegard. Zurich retained the status of an independent state in the German Empire, and joined the Swiss Confederation in 1351. Zwingli started the Swiss reformation while he was the main preacher in Zürich. He lived there from 1484 until his death in 1531. The prominent part taken by Zurich in adopting and propagating the principles of the Reformation finally secured it a position as the leader in the Swiss Confederation. Since the reformation, Zürich has remained the center and stronghold of Protestantism in Switzerland. During the French Revolutionary War, in 1799, it was the site of two battles. Zurich was also bombed, mistakenly, during World War II.

Name

The origin of the name is probably the Celtic word Turus, a corroborating reference to which was found on a tomb inscription dating from the Roman occupation in the second century; the antique name of the town in its romanized form was Turicum.

History

Early History (before 746)

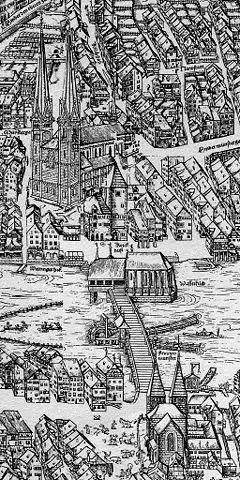

Numerous lake-side settlements from the Neolithic and Bronze age, such as those in the Zürich Pressehaus and Zürich Mozartstrasse, were discovered in the 1800s, submerged in Zürichsee (Lake Zürich). In 2004, traces of a previously unknown pre-Roman Celtic (La Tène culture) settlement were discovered (the center of which lay probably somewhat north of the Lindenhof, on the site of the Ötenbach monastery, removed wholesale in 1902). The nucleus of the ancient Roman settlement is on the Lindenhof, a hill between the Limmat and Sihl rivers. The Roman vicus of Turicum first belonged to the province of Gallia Belgica, and to Germania superior from 90 C.E.. Following Constantine's reform of the Empire in 318, the border between the praetorian prefectures of Gaul and Italy was just east of Turicum crossing the Linth between Lake Zürich and Walensee.

Roman Turicum was not fortified, but there was a small garrison set up, not exactly on the border, but downstream of Lake Zürich at the border of Gallia Belgica (from 90 C.E. Germania superior), to serve as a tax-collecting point and Raetia for goods trafficked on the Limmat river. South of the castle, at the location of the St. Peter church, there was a temple to Jupiter. The earliest record of the town's name is preserved on a second century tombstone found in the eighteenth century on Lindenhof, referring to the Roman castle as STA(tio) TUR(i)CEN(sis).

Felix and Regula

The saints Felix and Regula, together with their servant Exuperantius, are the patron saints of Zürich; their feast day is September 11.

According to legend, Felix and Regula were siblings, and members of the Christian Theban legion under Saint Maurice, stationed in Agaunum in the Valais. When the legion was to be executed in 286 for refusing to sacrifice to the Emperor, they fled, reaching Zürich via Glarus before they were caught, tried and executed. After being decapitated, they are said to have walked forty paces uphill. They were buried on the spot where they fell down.

The legend cannot be traced beyond an eighth century account, according to which the story was revealed to a monk called Florentius. In the ninth century there was a small monastery at the location. The Grossmünster was built on their graves from ca. 1100, while the Wasserkirche stands at the site of their execution. From the thirteenth century, images of the saints were used in official seals of the city and on coins. On the saints' feast day, their relics were carried in procession between the Grossmünster and the Fraumünster, and the two monasteries vied for possession of the relics, which attracted enough pilgrims to make Zürich the most important pilgrimage site in the bishopric of Konstanz. The Knabenschiessen of Zürich originates with the festival.

With the dissolution of the monasteries by Huldrych Zwingli in 1524, their possessions were confiscated and the graves of the martyrs were opened. There are conflicting versions of what happened then. Heinrich Bullinger claims that the graves were empty save for a few bone fragments, which were piously buried in the common graveyard outside the church. The Catholics, on the other hand, claimed that the reformers were planning to throw the relics of the saints into the river, and that a courageous man of Uri (who happened to be exiled from Uri, and by his action earned amnesty) stole the relics from the church and carried them to Andermatt, where the two skulls of Felix and Regula can be seen to this day, while the remaining relics were returned to Zürich in 1950, to the newly built Catholic church Saint Felix und Regula. The skulls have been Carbon 14 dated, and while one dates to the Middle Ages, the other is in fact composed of fragments of two separate skulls, of which one is medieval, and the other could indeed date to Roman times.

German Empire (746-1351)

The Alamanni settled in the Swiss plateau from the fifth century, but the Roman castle persisted into the seventh century. The earliest manuscript mention of the settlement, as castellum turegum, describes the mission of Columban in 610. An eighth century list of toponyms from Ravenna mentions Ziurichi. There is a legendary account of an Alamannic duke Uotila residing on, and giving his name to, the Üetliberg.

Zürich was part of Frankish ruled Alemannia from 746, following the blood court at Cannstatt, lying in the Turgowe (Thurgau) dominated by Konstanz. The Frankish kings had special rights over their tenants, were the protectors of the two churches, and had jurisdiction over the free community.

A Carolingian castle, built on the site of the Roman castle by the grandson of Charlemagne, Louis the German, is mentioned in 835 ("in castro Turicino iuxta fluvium Lindemaci"). Louis also founded the Fraumünster abbey in 853 for his daughter Hildegard. He endowed the Benedictine convent with the lands of Zürich, Uri, and the Albis forest, and granted the convent immunity, placing it under his direct authority.

In 870 the sovereign placed his powers over all four into the hands of a single official (the Reichsvogt), and the union was further strengthened by the wall built round the four settlements in the tenth century as a safeguard against Saracen marauders and feudal barons. The Reichsvogtei passed to the counts of Lenzburg (1063-1173), and then to the dukes of Zahringen.

In 1045, King Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor, granted the convent the right to hold markets, collect tolls, and mint coins, and thus effectively made the abbess the ruler of the city.

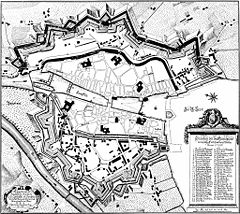

Zürich became reichsunmittelbar in 1218 with the extinction of the main line of the Zähringer family. The Reichsvogtei passed back into the hands of the king, who appointed one of the burghers as his deputy, the town thus becoming a free imperial city under the nominal rule of a distant sovereign. A city wall was built during the 1230s, enclosing 38 hectares. The Bahnhofstrasse marks the course of the western moat. The earliest citizens' stone houses at the Rennweg date to this period, using the dilapidated Carolingian castle as a quarry.

Emperor Frederick II promoted the abbess of the Fraumünster to the rank of a duchess in 1234. The abbess assigned the mayor, and she frequently delegated the minting of coins to citizens of the city. However, the political power of the convent slowly waned in the fourteenth century, beginning with the establishment of the Zunftordnung (guild laws) in 1336 by Rudolf Brun, who also became the first independent mayor not assigned by the abbess. Rudolf Brun brought about the admission of the craftsmen to a share in the town government, under a new constitution (the main features of which lasted till 1798) which created a Little Council made up of the burgomaster, thirteen members from the old patricians and wealthy burghers, and the thirteen masters of the craft gilds, each of the twenty-six holding office for six months.

Swiss Confederation

The new arrangement provoked a quarrel with one of the branches of the Habsburg family, in consequence of which Zürich joined the Swiss confederation (which at that time was a loose confederation of de facto independent states) as the fifth member in 1351. Zürich began extending its domain in 1362, and was expelled from the confederation in 1440 due to a war (the Old Zürich War) with the other member states over the territory of Toggenburg. Zürich was defeated in 1446, and re-admitted to the confederation in 1450. In 1467, Zurich completed her territorial expansion with the purchase of the town of Winterthur from the Habsburgs. Zurich’s trade connections with Italy led to involvement in the Burgundian war and the Italian campaign of 1512-1515.

The burgomaster Hans Waldmann (1483-1489), desiring to make Zurich a great commercial center, introduced many financial and moral reforms, and subordinated the interests of the country districts to those of the town. He was overthrown and executed in 1489, but his ideas were embodied in the constitution of 1498, which transferred all power to the guilds. Under the new constitution, which remained in force until 1798, the patricians became the first of the guilds, and; some special rights were also given to the subjects in country districts.

Zwingli started the Swiss reformation at the time when he was the main preacher in Zürich. He lived there from 1484 until his death in 1531. It was the prominent part taken by Zurich in adopting and propagating (against the strenuous opposition of the Constafel) the principles of the Reformation which finally secured for it the lead in the Swiss Confederation. The Frau Münster convent was suppressed in 1524 and the Catholic Mass abolished in 1525. Zürich became a haven for dissident intellectuals from all over Europe.

"Republic of Zürich" (1531-1798)

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the patriciate and council of Zürich adopted an increasingly aristocratic and isolationist attitude. A second ring of impressive city ramparts was built in 1624 under the impetus of the Thirty Years' War. Taxes to raise the funds required for this ambitious project were imposed on the subject territories without consultation, resulting in revolts that were crushed by force. From 1648, the city changed its official status from Reichsstadt to Republik, likening itself to city republics like Venice and Genova.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the town government began to concentrate power in the hands of a small committee of council members, and to ignore the provisions of the earlier constitutions and make important decisions without consulting the country districts. It was reckoned that around 1650, 9,000 privileged burghers extended their rule over 170,000 persons. Early in the eighteenth century, a determined effort was made to crush the flourishing rival silk trade in Winterthur by means of heavy duties. The French Revolution of 1789 sparked pro-libertarian demonstrations led by a club founded at Stäfa, south of Zürich, demanding the restoration of the liberties of 1489 and 1531; these were put down by force of arms in 1795.

Napoleonic Era (1798-1815)

The old system of government perished in Zurich, as elsewhere in Switzerland, in February 1798. Under the Helvetic constitution, the country districts obtained political liberty. Zürich lost much of its power in the Helvetic Republic, and was forced to cede territory to the Aargau, the Thurgau and the Canton of Linth. In 1799, the city twice became a battlefield of the French Revolutionary Wars of the Second Coalition. In the first battle on the 4th of June, the French under General André Masséna, on the defensive, were attacked by the Austrians under the Archduke Charles, Massena retiring behind the Limmat before the engagement had reached a decisive stage. The second and far more important battle took place on the 25th and 26th of September. Massena, having forced the passage of the Limmat, attacked and totally defeated the Russians and their Austrian allies under Korsakov's command.

Modern History (after 1815)

Züriputsch

On September 6, 1839, on the eve of the formation of the Swiss federal state, the rural conservative population rose up against the liberal rule of the city of Zürich. They viewed the appointment of the controversial German theologian David Strauss to the theological faculty of the University of Zürich by the liberal government as a danger to the old religious order in danger. Led by Bernhard Hirzel, pastor of Pfäffikon, several thousand “putschists” stormed the city from the west, and fought the cantonal troops in the alleys between Paradeplatz and Fraumünster. The last shot fired killed botanist and councillor Johannes Hegetschweiler as he delivered the city council's surrender.

Following the Züriputsch, the city had to yield to the demands of its urban subjects. Most of the ramparts built in the seventeenth century were torn down, without ever having been sieged, to allay rural concerns over the city's hegemony.

Nineteenth and twentieth centuries

The large-scale immigration from the country districts into the town, beginning in the 1830s, created an industrial class which, though "settled" in the town, did not possess the privileges of burghership, and consequently had no share in the municipal government. In 1860 the town schools, which had previously been opened to "settlers" who paid high fees, were made accessible to all. In 1875 it was declared that ten years' residence conferred the right of burghership, and in 1893 the eleven outlying districts (largely populated by the working class) were incorporated with the town proper.

The Treaty of Zurich between Austria, France, and Sardinia was signed in 1859. [3]

From 1847, the Spanisch-Brötli-Bahn, the first railway on Swiss territory, connected Zürich with Baden, putting the Zürich Main Station at the origin of the Swiss rail network. The present building of the Hauptbahnhof (chief railway station) dates to 1871. During the late nineteenth century, a city councillor, Alfred Escher, is credited with legislative innovations boosting tourism, banking and local manufacturing industry, which established Zürich as the economic capital of Switzerland. The Ötenbach monastery, founded 1285, fell victim to the increasingly grand city planning in 1902, with the entire hill it was built on removed to make way for the new Uraniastrasse and administration buildings. It had been serving as a prison, and the inmates were moved to the newly completed cantonal prison in Regensdorf.

During World War I, Switzerland’s strict neutrality made Zürich a refuge for dissidents; for several months in 1916 and 1917, the city was home to radical thinkers and writers including Vladimir Lenin and James Joyce, and a band of emigré artists calling themselves “Dada.” Though Switzerland was neutral territory, Zurich was accidentally bombed during WW II. After World War II Zurich flourished, becoming one of the world’s leading financial centers; today, Zürich is the single most important market for gold and precious metals, and boasts the world’s fourth-largest stock market after New York, London and Tokyo.

Coat of Arms

The blue and white coat of arms of Zürich is attested from 1389, and was derived from banners with blue and white stripes in use since 1315. The first certain documentation of banners with the same design is from 1434. The coat of arms is flanked by two lions. The red Schwenkel on top of the banner had varying interpretations; for the people of Zürich, it was a mark of honor, granted by Rudolph I. Zürich's neighbors mocked it as a sign of shame, commemorating the loss of the banner at Winterthur in 1292.

Today, the Canton of Zürich uses the same coat of arms as the city.

Geography

The city of Zurich is situated where the river Limmat issues from the north-western end of Lake Zürich. Zürich is surrounded by wooded hills including (from the north) the Gubrist, the Hönggerberg, the Käferberg, the Zürichberg, the Adlisberg and the Oettlisberg on the eastern shore; and the Uetliberg (part of the Albis range) on the western shore. The river Sihl meets with the Limmat at the end of Platzspitz, which borders the Swiss National Museum (Landesmuseum). The geographic (and historic) center of the city is the 'Lindenhof' a small natural hill on the left bank of the river Limmat, about 700 meters north of where the river issues from Lake Zürich. Today the incorporated city stretches somewhat beyond the natural hydrographic confines given by its hills and includes some neighborhoods to the northeast in the Glattal (valley of the river Glatt).

Climate

| Weather averages for Zürich, Switzerland | |||||||||||||

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avg high °C (°F) | 2 (36) | 3 (38) | 8 (47) | 12 (54) | 16 (62) | 19 (67) | 22 (73) | 22 (72) | 18 (65) | 12 (55) | 6 (43) | 3 (38) | 12 (54) |

| Avg low °C (°F) | -1 (29) | -1 (29) | 2 (36) | 4 (40) | 8 (48) | 11 (53) | 14 (58) | 13 (57) | 11 (52) | 7 (45) | 2 (36) | 0 (32) | 7 (43) |

| Precipitation cm (in) | 6 (2.4) | 6 (2.4) | 6 (2.7) | 8 (3.3) | 10 (4) | 12 (5) | 12 (5) | 12 (4.9) | 9 (3.9) | 8 (3.3) | 7 (2.8) | 7 (2.8) | 107 (42.3) |

| Source: Weatherbase[4] Jun 2013 | |||||||||||||

City districts

The old system of government perished in Zurich, as elsewhere in Switzerland, in February 1798. Under the Helvetic constitution, the country districts obtained political liberty. Zürich lost much of its power in the Helvetic Republic, and was forced to cede territory to the Aargau, the Thurgau and the Canton of Linth. In 1799, the city twice became a battlefield of the French Revolutionary Wars of the Second Coalition. In the first battle on the 4th of June, the French under General André Masséna, on the defensive, were attacked by the Austrians under the Archduke Charles, Massena retiring behind the Limmat before the engagement had reached a decisive stage. The second and far more important battle took place on the 25th and 26th of September. Massena, having forced the passage of the Limmat, attacked and totally defeated the Russians and their Austrian allies under Korsakov's command.

Modern History (after 1815)

Züriputsch

On September 6, 1839, on the eve of the formation of the Swiss federal state, the rural conservative population rose up against the liberal rule of the city of Zürich. They viewed the appointment of the controversial German theologian David Strauss to the theological faculty of the University of Zürich by the liberal government as a danger to the old religious order in danger. Led by Bernhard Hirzel, pastor of Pfäffikon, several thousand “putschists” stormed the city from the west, and fought the cantonal troops in the alleys between Paradeplatz and Fraumünster. The last shot fired killed botanist and councillor Johannes Hegetschweiler as he delivered the city council's surrender.

Following the Züriputsch, the city had to yield to the demands of its urban subjects. Most of the ramparts built in the seventeenth century were torn down, without ever having been sieged, to allay rural concerns over the city's hegemony.

Nineteenth and twentieth centuries

The large-scale immigration from the country districts into the town, beginning in the 1830s, created an industrial class which, though "settled" in the town, did not possess the privileges of burghership, and consequently had no share in the municipal government. In 1860 the town schools, which had previously been opened to "settlers" who paid high fees, were made accessible to all. In 1875 it was declared that ten years' residence conferred the right of burghership, and in 1893 the eleven outlying districts (largely populated by the working class) were incorporated with the town proper.

The Treaty of Zurich between Austria, France, and Sardinia was signed in 1859. [5]

From 1847, the Spanisch-Brötli-Bahn, the first railway on Swiss territory, connected Zürich with Baden, putting the Zürich Main Station at the origin of the Swiss rail network. The present building of the Hauptbahnhof (chief railway station) dates to 1871. During the late nineteenth century, a city councillor, Alfred Escher, is credited with legislative innovations boosting tourism, banking and local manufacturing industry, which established Zürich as the economic capital of Switzerland. The Ötenbach monastery, founded 1285, fell victim to the increasingly grand city planning in 1902, with the entire hill it was built on removed to make way for the new Uraniastrasse and administration buildings. It had been serving as a prison, and the inmates were moved to the newly completed cantonal prison in Regensdorf.

During World War I, Switzerland’s strict neutrality made Zürich a refuge for dissidents; for several months in 1916 and 1917, the city was home to radical thinkers and writers including Vladimir Lenin and James Joyce, and a band of emigré artists calling themselves “Dada.” Though Switzerland was neutral territory, Zurich was accidentally bombed during WW II. After World War II Zurich flourished, becoming one of the world’s leading financial centers; today, Zürich is the single most important market for gold and precious metals, and boasts the world’s fourth-largest stock market after New York, London and Tokyo.

Coat of Arms

The blue and white coat of arms of Zürich is attested from 1389, and was derived from banners with blue and white stripes in use since 1315. The first certain documentation of banners with the same design is from 1434. The coat of arms is flanked by two lions. The red Schwenkel on top of the banner had varying interpretations; for the people of Zürich, it was a mark of honor, granted by Rudolph I. Zürich's neighbors mocked it as a sign of shame, commemorating the loss of the banner at Winterthur in 1292.

Today, the Canton of Zürich uses the same coat of arms as the city.

Geography

The city of Zurich is situated where the river Limmat issues from the north-western end of Lake Zürich. Zürich is surrounded by wooded hills including (from the north) the Gubrist, the Hönggerberg, the Käferberg, the Zürichberg, the Adlisberg and the Oettlisberg on the eastern shore; and the Uetliberg (part of the Albis range) on the western shore. The river Sihl meets with the Limmat at the end of Platzspitz, which borders the Swiss National Museum (Landesmuseum). The geographic (and historic) center of the city is the 'Lindenhof' a small natural hill on the left bank of the river Limmat, about 700 meters north of where the river issues from Lake Zürich. Today the incorporated city stretches somewhat beyond the natural hydrographic confines given by its hills and includes some neighborhoods to the northeast in the Glattal (valley of the river Glatt).

The official language used by the government and in most publications is German, while the most commonly spoken language in Zürich is Zürichdeutsch (Zürich German), which is a local dialect of Swiss-German. Zürich German is the mother-tongue of 77 percent of the population.[6]

Religion

Since the Reformation led by Huldrych Zwingli, Zürich has remained the center and stronghold of Protestantism in Switzerland. During the course of the twentieth century, this has changed slightly; Catholics now make up the largest religious group in the city, with 33.3 percent. There has been strong growth in the Muslim community in Zürich in recent years. In the last 10 years the number of Muslims has doubled, from around 9,000 people to 20,000 people (2000).[7] Increasing numbers declare themselves as being without a religious affiliation (16.8 percent of the population in 2000).

Sights

Churches

- Grossmünster (Great Minster) (near Lake Zürich, in the old city), where Zwingli was pastor; first built around 820; declared by Charlemagne as an imperial church

- Fraumünster (Our Lady's Minster) first church, built before 874; the Romanesque choir dates from 1250-1270; Marc Chagall stained glass choir windows; (on the opposite side of the Limmat). During 2004, the Fraumünster was fully renovated. During this period the installed scaffolding went above the tip of the tower, allowing a unique and exceptional 360° panoramic view of Zürich.

- Saint Peter (downstream from the Fraumünster, in the old city); with the largest clock face in Europe

Museums

- Museum Bärengasse, history of the city in the seventeenth century

- Kunsthaus Zürich, one of the largest collections in Classic Modern Art in the world (Munch, Picasso, Braque, Giacometti, etc.) [8]

- Museum Rietberg, Arts of Asia, Africa, America and Oceania [9]

- Museum Bellerive, Museum for fashion, architecture and design [10], located in a villa on the beach of the lake

- Kunsthalle Zürich [11]

- Migros Museum, modern and avantgarde international Art. [12]

- Museum of Design Zürich [13]

- Swiss National Museum (Landesmuseum) [14], located in the Platzspitz park opposite to the main station

- Johann Jacobs Museum, history of colonial fine food and coffee [15]

- Johanna Spyri Museum [16]

- Haus Konstruktiv[17], constructive, concrete and conceptual art and design

- NONAM North American Native Museum [18].

- Museum of the History of Medicine

Other sights

- Lindenhof near Saint Peter; site of the Roman and medieval castle.

- Guild houses along the river (downstream from the Grossmünster)

- Old town (Altstadt), District 1, on both sides of the river

- Bahnhofstrasse, Zürich (shopping avenue) starting at main train station

- Parade-Platz, Plaza in the middle of Bahnhofstrasse, Zürich, a center of financial activity, with the world-headquarters of several Swiss banks including UBS and Credit Suisse.

- Zoological garden [19]

- Masoala Rainforest Ecosystem Great Glass Hall in the Zoological garden with trees, flowers and animals in liberty from the rainforest of Masoala National Park in Madagascar [20]

- Botanical Garden of the University of Zürich [21]

- Chinese Garden, Zürich[22]

- Neu Oerlikon, part of City District Oerlikon: northern quarter of the city - Oerliker Park, MFO Park, Center-11 Building, Price Waterhouse Building, ABB Building, UBS Building, and other modern public spaces. [23]

- Lake Zürich, running from Zürich to Rapperswil and linking with the Obersee

- Üetliberg, a hill to the west of the city at an altitude of 813 meters above sea level, with Uetlibergturm TV-tower

- Fluntern Cemetery

- Cabaret Voltaire, birthplace of Dada

Business, Industry and Commerce

UBS, Credit Suisse, Swiss Re, and many other financial institutions have their headquarters in Zürich, the commercial center of Switzerland. Zürich is the world's primary centre for offshore banking, mainly due to Swiss bank secrecy policies. The financial sector accounts for about one quarter of the city's economic activities. The Swiss Stock Exchange is also located in Zürich (see also Swiss banking).

Zürich is a leading financial centre and has repeatedly been proclaimed the global city with the best quality of life anywhere in the world. The Greater Zurich Area is Switzerland’s economic center and home to a vast number of international companies. In 2005, the GDP of the Zürich Area was CHF 210 billion (USD 160 billion) or CHF 58,000 (USD 45,000) per capita.

The Greater Zürich Economic Area has used aggressive strategies to attract large corporations and service/research centers, such as IBM, General Motors Europe, Google, Microsoft,Dow Chemical, and Pfizer. It offers a very low tax rate and the possibility for foreign companies and private persons to optimize their tax burden by negotiating a customized tax agreement with the Tax Authorities. The absence of an inheritance tax in Switzerland is also an important attraction for wealthy private individuals.

Zürich also has an extensive research and educational (Research and Development) area, located alongside the University of Zurich which has more than 58,000 students.

A new multi-purpose area in southern Zurich (Sihlcity)[24], spread over 100,000 square meters in the center of Zurich, opened its doors on March 22, 2007. Built on the foundations of the former Sihl Paper Factory, it includes a shopping center and a movie theater.

The high quality of life has been cited as a likely reason for the active international economic growth in Zürich. Mercer has ranked Zürich as the city with the highest quality of life anywhere in the world[25] for the fourth consecutive time. Berne and Geneva were also ranked among the Top 10. Statistics show that in the productive sector of the city 60 percent speak German, 43 percent English, 30 percent French and 13 percent Italian. The city is home to a considerable number of people speaking at least two or three languages.

Another factor which contributes to economic growth is Zurich’s extremely low crime rates.

The Swiss Stock Exchange

The Swiss stock exchange is called SWX Swiss Exchange. The SWX is the head of several different worldwide operative financial systems: virt-x, Eurex, Eurex US, EXFEED and STOXX. In 2004, the exchange turnover generated 1,244,045 million Swiss francs (CHF); the number of transactions for the same period was 14,697,381, and the Swiss Performance Index (SPI) arrived at a total market capitalization of 780,320 million CHF.

The SWX Swiss Exchange goes back more than 150 years. In 1996, fully electronic trading replaced the traditional floor trading system at the stock exchanges of Geneva (founded in 1850), Zurich (1873) and Basle (1876).

The SWX is subject to Swiss law. The Federal Act on Stock Exchanges and Securities Trading (SESTA) prescribes the concept of self-regulation, which obligates the SWX to meet international standards in its regulatory activities. The SWX itself is supervised by the Swiss Federal Banking Commission (SFBC).

The shares traded on SWX are mainly held in the Swiss-based accounts of domestic and international investors. Other products traded on the SWX Platform are bonds (CHF-denominated bonds as well as international bonds), traditional investments, Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs, known as exchange-traded index funds) and non-standardized derivatives. In terms of turnover, the SWX Swiss Exchange operates Europe's largest market segment for listed and exchange-traded warrants.

Educational and Research Institutions

- ETH Zürich

- University of Zürich

- IBM Zürich Research Laboratory. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Swiss Re's Centre for Global Dialogue. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- SIK Swiss Institute for Art Research - Schweizerisches Institut für Kunstwissenschaften. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- HGKZ - University of Applied Sciences and Designs. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Avenir Suisse - Liberal Think Tank. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Swiss Institute of International Studies.

- HMT School of Music, Drama and Dance - Hochschule für Musik und Theater. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ZFH College of Applied Sciences and Technologies Zurich - Zürcher Fachhochschule. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Graduate School of Business Administration Zurich. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- National Centre of Competence in Research - Financial Valuation and Risk Management. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Inter-Community School Zürich

- Zurich International School. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- SBS Swiss Business School

Media

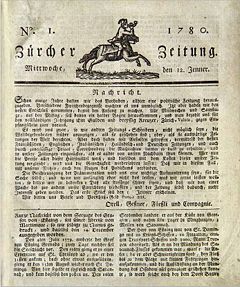

Many large Swiss media conglomerates, such as tamedia, Ringier and the NZZ-Verlag, are headquartered in Zürich. Because of this, Zürich is one of the most important media locations in the German-speaking part of Switzerland. The headquarters of Switzerland's national German-language television network (SF), and the regional television network TeleZüri (Zürich Television) have their headquarters in Zurich. The production facilities for private networks Star TV, u1 TV and 3+ are located in Schlieren. One division of the Swiss German-language public radio station DRS is located in Zürich, and several local radio stations broadcast from there.

Daily Newspapers and Magazines

Three large daily newspapers, The Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ), the Tages-Anzeiger and Blick, the largest Swiss tabloid, are published in Zürich and distributed across Switzerland. Besides the three main daily newspapers, there are several free daily newspapers.

Magazines

- Die Weltwoche

- Facts. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Die Wochenzeitung WOZ. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Finanz und Wirtschaft. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Cash. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Tachles. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Sonntags-Blick. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- P.S. Zeitung. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Bilanz. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

Δ

Culture

Events

- Street Parade

- Sechseläuten, spring festival of the guilds and burning of the Böögg

- Zurich International Theater Festival - Zürcher Theater Spektakel; it ranks among the most important European festivals for the contemporary performing arts. [26]

- Kunst Zürich, international art fair with an annual guest city (New York in 2005); combines the most recent art with the works of well-established artists. [27]

- Annual public art program each summer, sponsored by the Zürich City Association (the local equivalent of a chamber of commerce) with the cooperation of the city government. The theme for 2005 was teddy bears.

- Weltklasse Zürich, annually in August [www.weltklasse.ch]

- freestyle.ch, one of the biggest freestyle events in Europe. [28]

Art movements born in Zürich

- Zürich is the home of the Cabaret Voltaire where the Dada movement began in 1916. The Cabaret Voltaire Museum is at Spiegelgasse/Niederdorf-Corner.

- The Constructive Art Movement also took one of its first steps in Zurich. Artists like Max Bill, Marcel Breuer, Camille Graeser and Richard Paul Lohse had their ateliers in Zurich, which became even more important after the takeover of power by the Nazi-Regime in Germany and World War Two. Visit the museum at the Haus Konstruktiv.

Opera, Ballet and Theaters

- Zürcher Opernhaus: one of the most famous Opera Houses in Europe. Director is Alexander Pereira. Once a year an elegant and exclusive Zürcher Opernball is held there, with the President of the Swiss Confederation and the economic and cultural élite of Switzerland.[29] In front of the Lake Zürich and Bellevue-Place, where the traditional Sechseläuten takes place. Famous Ballet-Academy by Heinz Spoerli. Antique Neo-baroque interior very elegant and worth visiting.

- Schauspielhaus Zürich: Main Theater-Complex of the City. Has two Dépendances: Pfauen (historic old theater) in the Central City District and Schiffbauhalle (modern architecture in old industry-halls) in Zürich West. Was home for emigrants like Bertolt Brecht and Thomas Mann, and World-Première-Theater for Max Frisch, Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Botho Strauss and Nobel-Prize winner Elfriede Jelinek.[30]

- Theater am Neumarkt: One of the oldest Theaters of the city. Established by the old guilds in the Old City District, located in a baroque Palace near Niederdorf Street. Two stages with mostly production by avantgarde directors from Europe. Has both classic theater (Racine, Goethe, Shakespeare) and new productions in its repertoire.[31]

- Theater Gessnerallee: Young and underground Theater. The most experimental stage in the city. [32]

- Theater an der Sihl: Official theater of the Zürich Academy of Dance and Theater.[33] Next to the Theater Gessnerallee and the Bahnhofstrasse - the main shopping street of the city.

- Rote Fabrik Theater: The Rote Fabrik Cultural Complex is located on the shores of the lake in the district of Wollishofen. An avantgarde venue for young and controversial theater and ballet productions, in the great red brick halls of a nineteenth century textile mill.

- Theater Miller's Studio: Cabaret- and Revue-Theater with political and social comedy. A lot of one-man-shows. In the old Tiefenbrunnen-Complex with Restaurants, Bars, Museums (NONAM and Alte Mühle Tiefenbrunnen), Art-Galleries. In front of the lake. Take S-Bahn to Tiefenbrunnen Station.[34]

- Zurich Comedy Club: Much of Zurich's theatre is conducted in the native German. However, twice per year (May & November) this amateur theater group stages English-language theatre ranging from Shakespearean drama, to thrillers & drama of all kinds, pantomimes and of course comedies.[35]

Nightlife and clubbing

Zürich offers a lot of variety when it comes for night-time leisure. It became one of the capitals of Europe's electronic music scene and is the host city of the world-famous Street Parade, which takes place in August every year. The most famous districts for Nightlife are the Niederdorf in the old town with bars, restaurants, lounges, hotels, clubs, and fashionable shops for a young and stylish; and the Langstrasse in the districts 4 and 5 of the city. During the past ten years, new parts of the city have come into the spotlight, such as the area known as Zürich West in district 5, with its avant-garde cinemas, music clubs, lounges, restaurants, cafés and bars.

Sports

- Grasshopper-Club Zürich Football [36] (German)

- ZSC Lions Ice Hockey Club [37] (German)

- FC Zürich Football Club [38] (German)

- Challengers Baseball Club Zürich [39]

- Zürich Lions Baseball Club [40]

- Zürich Renegades American Football Club [41] (German)

- Federation Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) headquarters.

- Weltklasse Zürich

- International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF)

Sister Cities

- San Francisco

- Kunming

Notable people

People who were born or died in Zürich:

- Huldrych Zwingli (1484 - 1531), reformer

- Conrad Gessner (1516 - 1565), naturalist, born and died in Zürich

- Johann Jakob Scheuchzer (1672 - 1733), scholar, born in Zürich

- Johann Kaspar Lavater (1741 - 1801), poet and physiognomist, born in Zürich

- Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746 - 1827), educational reformer, born in Zürich

- James Sadleir (c. 1815 - 1881), fugitive swindler, murdered in Zürich

- Gottfried Keller (1819 - 1890), poet, born and died in Zürich

- Conrad Ferdinand Meyer (1825 - 1898), poet, born in Zürich

- Johanna Spyri (1827 - 1901), author of Heidi, died in Zürich

- Grand Duchess Marie Alexandrovna of Russia (1853) - (1920) Duchess of Edinburgh, died in Zürich

- Wilhelm Filchner (1877 - 1957), explorer, died in Zürich

- James Joyce (1882 - 1941), Irish novelist, died in Zürich (buried at Fluntern cemetery in Zürich)

- Pancho Vladigerov (1899 - 1978), Bulgarian composer, born in Zürich

- Felix Bloch (1905 - 1983), physicist, born in Zürich

- Elias Canetti (1905 - 1994), novelist, died in Zürich

- Max Frisch (1911 - 1991), novelist, born and died in Zürich

- Hugo Koblet (1925 - 1964), cycling champion

- Bruno Ganz (born 1941), actor, born in Zürich

- Martin Suter (born 1948), author, born in Zürich

- Lucinda Ruh (born 1979), figure skater, born in Zürich

- Heinz Günthardt (born 1959), professional tennis player, born in Zürich

Famous residents:

- Tristan Tzara (1915-1919)

- Richard Wagner (1849–1861)

- Albert Einstein (1896–1900, 1909–1911, 1912–1914)

- Vladimir Lenin (1917)

- Thomas Mann (1933–1942)

- Kurt Tucholsky (1932–1933)

- James Joyce (1915–1919)

- Harald Naegeli

- Tina Turner

- Elisabeth Schwarzkopf

- Andreas Vollenweider

- Moritz Leuenberger

- Kimi Räikkönen

- Fernando Alonso

- Yves Netzhammer

See also: List of mayors of Zürich

Notes

- ↑ Mercer Consulting. The world’s best cities are still in Switzerland. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Highlights from the 2007 Quality of Living Survey, MERCER. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ see New_International_Encyclopedia

- ↑ Weatherbase: Historical Weather for Zurich, Switzerland

- ↑ see New_International_Encyclopedia

- ↑ Statistical Office of the City of Zürich. Population Numbers Flyer (German). Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Statistics Data. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Kunsthaus Zürich. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Museum Rietberg. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Museum Bellerive. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Kunsthalle Zürich.

- ↑ Migros Museum. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Museum of Design Zürich. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Swiss National Museum. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Johann Jacobs Museum. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Johanna Spyri Museum. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Haus Konstruktiv. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ NONAM. Retrieved September 22, 2007

- ↑ Zürich Zoo. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Masoala Rainforest Ecosystem. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Botanical Garden of the University of Zürich. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Chinese Garden, Zürich. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Neu Oerlikon.

- ↑ Sihlcity. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Worldwide Quality of Living Survey accessdate 2006-12-11

- ↑ Theater spektakel. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Kunst Zürich. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ [www.freestyle.ch freestyle.ch]. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ opernhaus. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Schauspielhaus. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Theaterneumarkt. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Gessnerallee. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Theater der Kunst. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Millers Studio. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Zurich Comedy Club. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Grasshopper-Club Zürich. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ ZSC Lions. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Fussballclub Zürich. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Challengers Baseball Club Zürich. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Zürich Lions Baseball Club. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Zürich Renegades American Football Club.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dickerman, Leah, and Brigid Doherty. 2005. Dada: Zurich, Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, New York, Paris. Washington, [DC]: National Gallery of Art in association with D.A.P./ Distributed Art Publishers, New York. ISBN 0894683136

- Hillerbrand, Hans Joachim. 1968. The Protestant Reformation. Documentary history of Western civilization. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0061313424

- Taplin, Mark. 2003. The Italian reformers and the Zurich church, c. 1540-1620. St. Andrews studies in Reformation history. Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate. ISBN 0754609782 9780754609780

- Wandel, Lee Palmer. 1990. Always among us: images of the poor in Zwingli's Zurich. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521390966

- Zurich. 2007. Cityspots. Peterborough: Thomas Cook. ISBN 9781841577678

External links

All links retrieved June 13, 2023.

- Stadt Zürich (German) Official site.

- Zürich Tourism Official site.

- Zurich Comedy Club - English Language Theatre in Zurich

- English Forum, Non-commercial English language community website for Zurich.

- CPG 111, 1470s manuscript containing the legend of Felix and Regula as well as that of Saint Meinrad.

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Zurich history

- Zuriputsch history

- Felix_and_Regula history

- Theban_Legion history

- History_of_Zurich history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

![Zürich [zoom] (Switzerland)](/d/images/thumb/c/cf/Karte_Schweiz.png/265px-Karte_Schweiz.png)