Difference between revisions of "Violence" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (127 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} | |

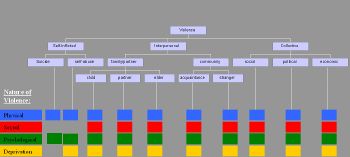

[[File:Typology of violence.jpg|thumb|350px|Typology of violence]] | [[File:Typology of violence.jpg|thumb|350px|Typology of violence]] | ||

| − | + | '''Violence''' is defined as "the use of physical force so as to injure, abuse, damage, or destroy."<ref>[https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/violence Definition of violence] ''Merriam Webstier Dictionary''. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> Less conventional definitions are also used, such as the [[World Health Organization]]'s definition of violence as "the intentional use of physical force or [[Power (social and political)|power]], threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, which either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation."<ref name="who.int"> [https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/ World report on violence and health] ''World Health Organization''. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | '''Violence''' is defined as "the use of physical force so as to injure, abuse, damage, or destroy."<ref>[https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/violence Definition of violence] ''Merriam Webstier Dictionary''. Retrieved | ||

Violence often has lifelong consequences for physical and mental health and social functioning and can slow economic and social development. | Violence often has lifelong consequences for physical and mental health and social functioning and can slow economic and social development. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Violence in many forms can be preventable. There is a strong relationship between levels of violence and modifiable factors in a country such as [[poverty]], [[income]], and [[gender]] inequality, the harmful use of [[alcohol]] and [[drug]]s, and the absence of safe, stable, and nurturing relationships between [[children]] and [[parent]]s in the [[family]]. Strategies addressing these underlying causes of violence can be relatively effective in prevention. | ||

| − | + | == History == | |

| + | Scholars are divided on the origins of organized, large-scale, militaristic, or regular human-on-human violence — in other words, [[war]]-like behavior: | ||

| + | <blockquote>There are basically two schools of thought on this issue. One holds that warfare ... goes back at least to the time of the first thoroughly modern humans and even before then to the primate ancestors of the hominid lineage. The second position on the origins of warfare sees war as much less common in the cultural and biological evolution of humans. Here, warfare is a latecomer on the cultural horizon, only arising in very specific material circumstances and being quite rare in human history until the development of agriculture in the past 10,000 years.<ref name=Fry>Douglas P. Fry, (ed.), ''War, Peace, and Human Nature: The Convergence of Evolutionary and Cultural Views'' (Oxford University Press, 2015, ISBN 0190232463).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | The idea of the peaceful pre-history and non-violent tribal societies gained popularity with the [[Postcolonialism|post-colonial perspective]]. The trend, starting in [[archaeology]] and spreading to [[anthropology]], reached its height in the late half of the twentieth century. This latecomer view of warfare, espoused by [[Jared Diamond]] in his books ''[[Guns, Germs and Steel]]'' and ''[[The Third Chimpanzee]]'', posits that the rise of large-scale warfare is the result of advances in [[technology]] and [[city-state]]s. For instance, the rise of [[agriculture]] provided a significant increase in the number of individuals that a region could sustain over [[hunter-gatherer]] societies, allowing for [[division of labor]] and the development of specialized classes such as [[soldier]]s, or [[weapon]]s manufacturers. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Others argue that violence within and among groups is not a recent phenomenon but is a behavior that is found throughout human history: <blockquote>Human violence is an inescapable aspect of our society and culture. As the archaeological record clearly shows, this has always been true.<ref>Debra L. Martin, Ryan P. Harrod, and Ventura R. Pérez (eds.), ''The Bioarchaeology of Violence'' (University Press of Florida, 2013, ISBN 0813049504)</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Religious texts support this view, describing the [[murder]] taking place in the first family of our human ancestors, when [[Cain]] killed his brother [[Abel]] (Genesis 4:8). | |

| − | + | Violence has been documented in the [[Holocene]], an epoch that began about 11,500 years ago.<ref>R. Dale Guthrie, ''The Nature of Paleolithic Art'' (University of Chicago Press, 2006, ISBN 0226311260).</ref> Lawrence H. Keeley in ''[[War Before Civilization]]'' writes that 87 percent of [[tribal societies]] were at war more than once per year, and that 65 percent of them were fighting continuously. He argues that the "primitive" warfare of these small groups or tribes was driven by the basic need for sustenance.<ref>Lawrence H. Keeley, ''War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage'' (Oxford University Press, 1997, ISBN 0195119126).</ref> The attrition rate of numerous close-quarter clashes, which characterize such [[endemic warfare]], produces casualty rates of up to 60 percent.<ref>Robert Wilfred Franson, [http://www.troynovant.com/Franson/Keeley/War-Before-Civilization.html Review of book "War Before Civilization" by Lawrence H. Keeley] ''Troynovant'', July 2004. Retrieved June 19, 2020. </ref> | |

| − | [[ | + | Douglas Fry, however, has argued that such sources erroneously focus on the [[ethnography]] of hunters and gatherers in the present, whose culture and values have been infiltrated externally by modern civilization, rather than the actual archaeological record spanning some two million years of human existence. He claims that all contemporary tribal societies, "by the very fact of having been described and published by anthropologists, have been irrevocably impacted by history and modern colonial nation states" and that "many have been affected by state societies for at least 5000 years."<ref name=Fry/> |

| − | Steven Pinker | + | A third position, posited by [[Steven Pinker]] in his 2011 book, ''The Better Angels of Our Nature'', roused both acclaim and controversy by asserting that modern society is less violent than in periods of the past, whether on the short scale of decades or long scale of centuries or millennia. He argued that by every possible measure, every type of violence has drastically decreased since ancient and [[medieval]] times. A few centuries ago, for example, [[genocide]] was a standard practice in all kinds of warfare and was so common that historians did not even bother to mention it. According to Pinker, [[rape]], [[murder]], warfare, and animal cruelty have all seen drastic declines in the twentieth century.<ref>Steven Pinker, ''The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined'' (Viking, 2011, ISBN 0670022950).</ref> However, Pinker's analyses have met with much criticism.<ref>Robert Epstein, [http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=bookreview-steven-pinker-the-better-angels-of-our-nature-why-violence-has-declined Book Review: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined] ''Scientific American'', October 7, 2011. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref><ref>Ben Laws, [http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=702 Against Pinker's Violence] ''CTheory'', March 21, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> |

== Epidemiology == | == Epidemiology == | ||

| − | + | Deaths due to self-harm and interpersonal violence resulted in about 1.34 million deaths in 2010, up from about 1 million in 1990, while deaths due to collective violence decreased from 64,000 in 1990 to 17,700 in 2010.<ref name=Loz2012>R. Lozano, [https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(12)61728-0/fulltext Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010] ''Lancet'' 380(9859) (December 15, 2012): 2095–2128. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> By way of comparison, the 1.5 millions deaths a year due to all forms of violence is greater than the number of deaths due to [[tuberculosis]] (1.34 million), road traffic injuries (1.21 million), and [[malaria]] (830,000), but slightly less than the number of people who died from [[HIV/AIDS]] (1.77 million).<ref name=Loz2012 /> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The World Health Organization (WHO) 2014 publication on [[suicide]] reported that: | |

| + | <blockquote>An estimated 804,000 suicide deaths occurred worldwide in 2012, representing an annual global age-standardized suicide rate of 11.4 per 100 000 population (15.0 for males and 8.0 for females). However, since suicide is a sensitive issue, and even illegal in some countries, it is very likely that it is under-reported. In countries with good vital registration data, suicide may often be misclassified as an accident or another cause of death.<ref>[https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/131056/9789241564779_eng.pdf;jsessionid=35392AC9D454752889C2650049045812?sequence=1 Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative] World Health Organization, 2014. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Rates and patterns of violent death vary by country and region. Studies show a strong, inverse relationship between homicide rates and both economic development and economic equality. Poorer countries, especially those with large gaps between the rich and the poor, tend to have higher rates of [[homicide]] than wealthier countries. Homicide rates differ markedly by age and gender: For the 15 to 29 age group, male rates were nearly six times those for female rates; for the remaining age groups, male rates were from two to four times those for females.<ref> Dean T. Jamison et al. (eds.), ''Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries'' (World Bank Publications, 2006, ISBN 0821361791). </ref> | |

| − | [[ | + | For every death due to violence, there are numerous nonfatal injuries. Beyond deaths and injuries, forms of violence such as [[child abuse]], [[domestic violence|intimate partner violence]], and elder maltreatment are also prevalent. Forms of violence such as child maltreatment and intimate partner violence are highly prevalent. A quarter of all adults report having been physically abused as children; 1 in 5 women and 1 in 13 men report being sexually abused as children.<ref> [https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment Child maltreatment] ''World Health Organization'', September 30, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> A WHO multi-country study found that about 1 in 3 (35 percent) of women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime.<ref>WHO, [https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women Violence against women] ''World Health Organization'', November 29, 2017. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> |

| + | Successive editions of the ''Global Burden of Armed Violence'' reveal a continuous drop in the average annual number of violent deaths worldwide: from 540,000 violent deaths for the period 2004–2007 and 526,000 for 2004–2009, to 508,000 for 2007–2012. The average global rate of violent deaths stood at 7.4 persons killed per 100,000 population for the period 2007–2012.<ref name=Global>[http://www.genevadeclaration.org/measurability/global-burden-of-armed-violence/gbav-2015/executive-summary.html Executive Summary] ''Global Burden of Armed Violence 2015: Every Body Counts'', Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development, May 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Although there is a widespread perception that [[war]] is the most dangerous form of armed violence in the world, of the 508,000 violent deaths in the period 2007-2012, 70,000 were due to direct conflict, with a large proportion of the latter deaths due to armed conflict in [[Libya]] and [[Syria]]. In the same period were an annual average of 377,000 intentional homicides, 42,000 unintentional homicides, and 19,000 deaths due to legal interventions. Additionally, lethal violence rates in some countries that are not experiencing armed conflict, notably [[Honduras]] and [[Venezuela]], have risen to levels characteristic of countries at war.<ref name=Global/> | |

| − | + | This illustrates the value of accounting for all forms of armed violence rather than an exclusive focus on conflict related violence. Certainly, there are huge variations in the risk of dying from armed conflict at the national and subnational level, and the risk of dying violently in a conflict in specific countries remains extremely high. In Iraq, for example, the direct conflict death rate for 2004–2007 was 65 per 100,000 people per year in [[Iraq]] and in [[Somalia]] 24 per 100,000 people, with peak rates of 91 per 100,000 in Iraq in 2006 and 74 per 100,000 in Somalia in 2007.<ref>Keith Krause, Robert Muggah, and Achim Wennmann, [http://www.genevadeclaration.org/measurability/global-burden-of-armed-violence/global-burden-of-armed-violence-2008.html Global Burden of Armed Violence 2008] Geneva Declaration on Armed Violence and Development, 2008. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Impacts == | == Impacts == | ||

| + | Beyond deaths and injuries, highly prevalent forms of violence (such as child maltreatment and intimate partner violence) have serious lifelong non-injury health consequences. Victims may engage in high-risk behaviors such as [[alcohol]] and [[substance abuse]], and smoking, which in turn can contribute to [[clinical depression|depression]], cardiovascular disorders, [[cancer]]s, and other diseases resulting in premature death.<ref>[https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/index.html About Adverse Childhood Experiences] ''Centers for Disease Control and Prevention''. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | ||

| − | + | In countries with high levels of violence, economic growth can be slowed down, personal and collective security eroded, and social development impeded. Families edging out of [[poverty]] and investing in [[education|schooling]] their sons and daughters can be ruined through the violent death or severe disability of the main breadwinner. For societies, meeting the direct costs of health, criminal justice, and social welfare responses to violence diverts many billions of dollars from more constructive societal spending. The much larger indirect costs of violence due to lost productivity and lost investment in education work together to slow economic development, increase socioeconomic inequality, and erode human and social capital. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In countries with high levels of violence, economic growth can be slowed down, personal and collective security eroded, and social development impeded. Families edging out of poverty and investing in schooling their sons and daughters can be ruined through the violent death or severe disability of the main breadwinner | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Additionally, communities with high levels of violence do not provide the level of stability and predictability vital for a prospering business economy. Individuals will be less likely to invest money and effort towards growth in such unstable and violent conditions.<ref>Sarah Gust and Jörg Baten, Interpersonal violence in South Asia, 900-1900 Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, 2019. </ref> | |

== Types == | == Types == | ||

| + | Violence has been defined as the use of physical force. However, there are many actions that do not involve physical force which are nonetheless destructive, and can be classified as a type of violence: | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | For many people, ... only physical violence truly qualifies as violence. But, certainly, violence is more than killing people, unless one includes all those words and actions that kill people slowly. The effect of limitation to a “killing fields” perspective is the widespread neglect of many other forms of violence. We must insist that violence also refers to that which is psychologically destructive, that which demeans, damages, or depersonalizes others. In view of these considerations, violence may be defined as follows: any action, verbal or nonverbal, oral or written, physical or psychical, active or passive, public or private, individual or institutional/societal, human or divine, in whatever degree of intensity, that abuses, violates, injures, or kills. Some of the most pervasive and most dangerous forms of violence are those that are often hidden from view (against women and children, especially); just beneath the surface in many of our homes, churches, and communities is abuse enough to freeze the blood. Moreover, many forms of systemic violence often slip past our attention because they are so much a part of the infrastructure of life (e.g., racism, sexism, ageism).<ref>Terence Freitheim, [http://wordandworld.luthersem.edu/content/pdfs/24-1_Violence/24-1_Fretheim.pdf God and Violence in the Old Testament] ''Word & World'' 24(1) (Winter 2004):18-28. Retrieved June 19, 2020. </ref> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

The World Health Organization divides violence into three broad categories:<ref name="who.int" /> | The World Health Organization divides violence into three broad categories:<ref name="who.int" /> | ||

| Line 64: | Line 58: | ||

* collective violence | * collective violence | ||

| − | This initial categorization differentiates between violence a person inflicts upon himself or herself, violence inflicted by another individual or by a small group of individuals, and violence inflicted by larger groups such as [[state]]s, organized political groups, [[militia]] groups, and [[Terrorism|terrorist]] organizations. These three broad categories are each divided further to reflect more specific types of violence: | + | This initial categorization differentiates between violence a person inflicts upon himself or herself, violence inflicted by another individual or by a small group of individuals, and violence inflicted by larger groups such as [[state]]s, organized political groups, [[militia]] groups, and [[Terrorism|terrorist]] organizations. These three broad categories are each divided further to reflect more specific types of violence, broadening the definition beyond the use of physical force: |

* physical | * physical | ||

* sexual | * sexual | ||

* psychological | * psychological | ||

* emotional | * emotional | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=== Self-directed violence === | === Self-directed violence === | ||

| Line 76: | Line 68: | ||

=== Collective violence === | === Collective violence === | ||

| + | [[File:The Bochnia massacre German-occupied Poland 1939.jpg|thumb|right|250px|[[Massacre]] of [[Poles|Polish]] civilians during [[Nazi occupation of Poland]], 1939]] | ||

| − | [[ | + | '''Collective violence''' is subdivided into [[structural violence]] and [[economic violence]]. Unlike the other two broad categories, the subcategories of collective violence suggest possible motives for violence committed by larger groups of individuals or by states. Collective violence that is committed to advance a particular social agenda includes, for example, crimes of hate committed by organized groups, [[terrorist]] acts. and [[mob]] violence. Political violence includes [[war]] and related violent conflicts, state violence, and similar acts carried out by larger groups. Economic violence includes attacks by larger groups motivated by economic gain – such as attacks carried out with the purpose of disrupting economic activity, denying access to essential services, or creating economic division and fragmentation. Clearly, acts committed by larger groups can have multiple motives.<ref name=Allen>Josephine A.V. Allen, [https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1300/J137v04n02_03?journalCode=whum20 Poverty as a Form of Violence] ''Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment'' 4(2–3) (2001):45–59. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> |

| − | + | This typology, while imperfect and far from being universally accepted, does provide a useful framework for understanding the complex patterns of violence taking place around the world, as well as violence in the everyday lives of individuals, families, and communities. | |

| − | + | [[File:UStankParis-edit1.jpg|thumb|200px|right|A United States [[M8 Greyhound]] armored car in Paris during World War II]] | |

==== Warfare ==== | ==== Warfare ==== | ||

| + | {{Main|War}} | ||

| − | + | [[War]] is a state of prolonged violent large-scale conflict involving two or more groups of people, usually under the auspices of government. It is the most extreme form of collective violence. | |

| − | + | War is fought as a means of resolving territorial and other conflicts, as [[war of aggression]] to conquer territory or loot resources, in national [[self-defense]] or liberation, or to suppress attempts of part of the nation to [[secession|secede]] from it. There are also ideological, [[Religious war|religious]] and [[Revolution|revolutionary war]]s. | |

| − | |||

| − | War is fought as a means of resolving territorial and other conflicts, as [[war of aggression]] to conquer territory or loot resources, in national [[self- | ||

Since the [[Industrial Revolution]] the lethality of modern warfare has grown. [[World War I casualties]] were over 40 million and [[World War II casualties]] were over 70 million. | Since the [[Industrial Revolution]] the lethality of modern warfare has grown. [[World War I casualties]] were over 40 million and [[World War II casualties]] were over 70 million. | ||

=== Interpersonal violence === | === Interpersonal violence === | ||

| − | + | [[File:Schnorr von Carolsfeld Bibel in Bildern 1860 093.png|thumb|right|225px|''Saul attacks David'' (who had been playing music to help Saul feel better), 1860 woodcut by [[Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld]]]] | |

| − | [[File:Schnorr von Carolsfeld Bibel in Bildern 1860 093.png|thumb|right|''Saul attacks David'' (who had been playing music to help Saul feel better), 1860 woodcut by [[Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld]]]] | + | '''Interpersonal violence''' is divided into two subcategories: Family and [[intimate partner violence]] – that is, violence largely between family members and intimate partners, usually, though not exclusively, taking place in the home. Community violence – violence between individuals who are unrelated, and who may or may not know each other, generally taking place outside the home. The former group includes forms of violence such as [[child abuse]], intimate partner violence and [[elderly abuse|abuse of the elderly]]. The latter includes youth violence, random acts of violence, [[rape]] or [[sexual assault]] by strangers, and violence in institutional settings such as schools, workplaces, prisons and nursing homes. When interpersonal violence occurs in families, its psychological consequences can affect parents, children, and their relationship in the short- and long-terms.<ref>D.S. Schechter, et al., [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22170456 The relationship of violent fathers, posttraumatically stressed mothers, and symptomatic children in a preschool-age inner-city pediatrics clinic sample] ''Journal of Interpersonal Violence'' 26(18) (2011): 3699–3719. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> |

| − | '''Interpersonal violence''' is divided into two subcategories: Family and [[intimate partner violence]] – that is, violence largely between family members and intimate partners, usually, though not exclusively, taking place in the home. Community violence – violence between individuals who are unrelated, and who may or may not know each other, generally taking place outside the home. The former group includes forms of violence such as [[child abuse]], intimate partner violence and [[elderly abuse|abuse of the elderly]]. The latter includes youth violence, random acts of violence, [[rape]] or [[sexual assault]] by strangers, and violence in institutional settings such as schools, workplaces, prisons and nursing homes. When interpersonal violence occurs in families, its psychological consequences can affect parents, children, and their relationship in the short- and long-terms.<ref> | ||

==== Child maltreatment ==== | ==== Child maltreatment ==== | ||

{{Main|Child abuse}} | {{Main|Child abuse}} | ||

| − | Child maltreatment is the abuse and neglect that occurs to children under 18 years of age. It includes all types of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, [[child sexual abuse|sexual abuse]], [[neglect]], [[negligence]] and commercial or other [[child exploitation]], which results in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust, or power. Exposure to intimate partner violence is also sometimes included as a form of child maltreatment.<ref>World Health Organization | + | Child maltreatment is the abuse and neglect that occurs to children under 18 years of age. It includes all types of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, [[child sexual abuse|sexual abuse]], [[neglect]], [[negligence]] and commercial or other [[child exploitation]], which results in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust, or power. Exposure to intimate partner violence is also sometimes included as a form of child maltreatment.<ref>World Health Organization, [https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/violence/child_maltreatment/en/ Preventing child maltreatment: a guide to taking action and generating evidence] Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | There are no reliable global estimates for the prevalence of child maltreatment. Data for many countries, especially low- and middle-income countries, are lacking. Current estimates vary widely depending on the country and the method of research used. Approximately 20 | + | Child maltreatment is a global problem with serious lifelong consequences, which is, however, complex and difficult to study. There are no reliable global estimates for the prevalence of child maltreatment. Data for many countries, especially low- and middle-income countries, are lacking. Current estimates vary widely depending on the country and the method of research used. Approximately 20 percent of women and 5–10 percent of men report being sexually abused as children, while 25–50 percent of all children report being physically abused.<ref>M. Stoltenborgh, et al., [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21511741 A global perspective on child abuse: Meta-analysis of prevalence around the world] ''Child Maltreatment'' 26(2) (2011): 79-101. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> |

| − | Consequences of child maltreatment include impaired lifelong physical and mental health, and social and occupational functioning ( | + | Consequences of child maltreatment include impaired lifelong physical and mental health, and social and occupational functioning (for example, school, job, and relationship difficulties). These can ultimately slow a country's economic and social development.<ref>Ruth Gilbert, et al., [https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(08)61706-7/fulltext Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries] ''The Lancet'' 373(9657) (2009): 68–81. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> |

==== Youth violence ==== | ==== Youth violence ==== | ||

| − | + | Following the [[World Health Organization]], youth are defined as people between the ages of 10 and 29 years. Youth violence refers to violence occurring between youths, and includes acts that range from [[bullying]] and physical fighting, through more severe sexual and physical assault to [[homicide]].<ref name="who.int"/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Different types of youth on youth violence include witnessing or being involved in physical, emotional, and sexual abuse (physical attacks, [[bullying]], [[rape]], and so forth), and violent acts like [[gang]] shootings and robberies. According to researchers in 2018, "More than half of children and adolescents living in cities have experienced some form of community violence." The violence "can also all take place under one roof, or in a given community or neighborhood and can happen at the same time or at different stages of life."<ref name=Conversation>Darby Saxbe, [https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/living-with-neighborhood-violence-may-shape-teens-rsquo-brains/ Living with Neighborhood Violence May Shape Teens' Brains] ''Scientific American'', June 15, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2020. </ref> Youth violence has immediate and long term adverse impact whether the individual was the recipient of the violence or a witness to it.<ref>[https://vetoviolence.cdc.gov/consequences-youth-violence Youth Violence] ''Centers for Disease Control and Prevention''. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | + | Youth violence has a serious, often lifelong, impact on a person's psychological and social functioning. Youth violence greatly increases the costs of health, welfare, and criminal justice services; reduces productivity; decreases the value of property; and generally undermines the fabric of society. Youth violence impacts individuals, their families, and society. | |

| − | + | Recent research has found that psychological trauma during childhood can change a child's brain. <blockquote>Trauma is known to physically affect the brain and the body which causes anxiety, rage, and the ability to concentrate. They can also have problems remembering, trusting, and forming relationships.<ref name=Bessel>Bessel Van Der Kolk, ''The Body Keeps The Score'' (Penguin Books, 2015, ISBN 9780143127741).</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | + | Since the brain becomes used to violence it may stay continually in an alert state (similar to being stuck in the fight or flight mode). Youth who are exposed to violence may have emotional, social, and cognitive problems: They may have trouble controlling emotions, paying attention in school, withdraw from friends, or show signs of post-traumatic stress disorder.<ref name=Conversation/> | |

| − | + | Youth who have experienced violence benefit from having a close relationship with one or more people.<ref name=Bessel/> This is important because the trauma victims need to have people who are safe and trustworthy that they can relate and talk to about their horrible experiences. Some youth do not have adult figures at home or someone they can count on for guidance and comfort. Schools in bad neighborhoods where youth violence is prevalent should assign counselors to each student so that they receive regular guidance. In addition to counseling/therapy sessions and programs, it has been recommended that schools offer mentoring programs where students can interact with adults who can be a positive influence on them. Another way is to create more neighborhood programs to ensure that each child has a positive and stable place to go when school in not in session. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Youth who have experienced violence benefit from having a close relationship with one or more people.<ref name= | ||

==== Intimate partner violence ==== | ==== Intimate partner violence ==== | ||

| Line 131: | Line 114: | ||

Intimate partner violence refers to behavior in an intimate relationship that causes physical, sexual, or psychological harm, including physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse, and controlling behaviors.<ref name="who.int" /> | Intimate partner violence refers to behavior in an intimate relationship that causes physical, sexual, or psychological harm, including physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse, and controlling behaviors.<ref name="who.int" /> | ||

| − | + | Intimate partner and sexual violence have serious short- and long-term physical, mental, sexual, and reproductive health problems for victims and for their children, and lead to high social and economic costs. These include both fatal and non-fatal injuries, [[clinical depression|depression]], and [[post-traumatic stress disorder]], unintended [[pregnancy|pregnancies]], sexually transmitted infections, including [[HIV]].<ref>Sandra M. Stith, et al., [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1359178903000557 Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: a meta-analytic review] ''Aggression and Violent Behavior'' 10(1) (2004): 65–98. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | + | Factors associated with the perpetration and experiencing of intimate partner violence are low levels of education, history of violence as a perpetrator, a victim or a witness of parental violence, harmful use of alcohol, attitudes that are accepting of violence, as well as marital discord and dissatisfaction. Factors associated only with perpetration of intimate partner violence are having multiple partners, and [[antisocial personality disorder]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | Factors associated with the perpetration and experiencing of intimate partner violence are low levels of education, history of violence as a perpetrator, a victim or a witness of parental violence, harmful use of alcohol, attitudes that are accepting of violence as well as marital discord and dissatisfaction. Factors associated only with perpetration of intimate partner violence are having multiple partners, and [[antisocial personality disorder]]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==== Sexual violence ==== | ==== Sexual violence ==== | ||

{{Main|Sexual violence}} | {{Main|Sexual violence}} | ||

| − | [[File:DRC raped women.jpg|thumb|Meeting of victims of | + | [[File:DRC raped women.jpg|thumb|250px|Meeting of victims of sexual violence in the [[Democratic Republic of the Congo]].]] |

| − | Sexual violence is any sexual act | + | Sexual violence is any sexual act or attempt to obtain a sexual act by violence or coercion, acts to [[Trafficking in human beings|traffic]] a person, or acts directed against a person's sexuality, regardless of the relationship to the victim. It includes but is not limited to all forms of [[rape]].<ref name="who.int"/> |

| − | + | Sexual violence has serious short- and long-term consequences on physical, mental, sexual, and reproductive health for victims and for their children as described in the section on intimate partner violence. If perpetrated during childhood, sexual violence can lead to increased smoking, drug and alcohol misuse, and risky sexual behaviors in later life. It is also associated with perpetration of violence and being a victim of violence. | |

Many of the risk factors for sexual violence are the same as for [[domestic violence]]. Risk factors specific to sexual violence perpetration include beliefs in family honor and sexual purity, ideologies of male sexual entitlement and weak legal sanctions for sexual violence. | Many of the risk factors for sexual violence are the same as for [[domestic violence]]. Risk factors specific to sexual violence perpetration include beliefs in family honor and sexual purity, ideologies of male sexual entitlement and weak legal sanctions for sexual violence. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==== Elder maltreatment ==== | ==== Elder maltreatment ==== | ||

{{Main|Elder abuse}} | {{Main|Elder abuse}} | ||

| − | Elder maltreatment is a single or repeated act, or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust which causes harm or distress to an older person. This type of violence constitutes a violation of human rights and includes [[physical abuse|physical]], [[sexual abuse|sexual]], [[psychological abuse|psychological]], emotional | + | Elder maltreatment is a single or repeated act, or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust which causes harm or distress to an older person. This type of violence constitutes a violation of human rights and includes [[physical abuse|physical]], [[sexual abuse|sexual]], [[psychological abuse|psychological]], emotional, [[financial abuse|financial]], and material abuse; abandonment; [[neglect]]; and serious loss of [[dignity]] and [[respect]].<ref name="who.int" /> |

| − | + | Although there is little information regarding the extent of maltreatment in elderly populations, especially in developing countries, abuse of elders by caregivers is a worldwide issue. Older people are often afraid to report cases of maltreatment to family, friends, or to the authorities. Data on the extent of the problem in institutions such as hospitals, nursing homes and other long-term care facilities are scarce. Elder maltreatment can lead to serious physical injuries and long-term psychological consequences. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Factors == | == Factors == | ||

Violence cannot be attributed to a single factor. Its causes are complex and occur at different levels. To represent this complexity, the ecological, or [[social ecological model]] is often used. The following four-level version of the ecological model is often used in the study of violence: | Violence cannot be attributed to a single factor. Its causes are complex and occur at different levels. To represent this complexity, the ecological, or [[social ecological model]] is often used. The following four-level version of the ecological model is often used in the study of violence: | ||

| − | The first level identifies biological and personal factors that influence how individuals behave and increase their likelihood of becoming a victim or perpetrator of violence: demographic characteristics (age, education, income), [[Genetics of aggression|genetics]], [[ | + | The first level identifies '''biological and personal factors''' that influence how individuals behave and increase their likelihood of becoming a victim or perpetrator of violence: demographic characteristics (age, education, income), [[Genetics of aggression|genetics]], [[brain lesions]], [[personality disorders]], [[substance abuse]], and a history of experiencing, witnessing, or engaging in violent behavior.<ref name=Patrick>Christopher J. Patrick, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2606710/ Psychophysiological correlates of aggression and violence: An integrative review] ''Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences'' 363(1503) (2008): 2543–2555. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> |

| − | The second level focuses on close relationships, such as those with family and friends. In youth violence, for example, having friends who engage in or encourage violence can increase a young person’s risk of being a victim or perpetrator of violence. For intimate partner violence, a consistent marker at this level of the model is marital conflict or discord in the relationship. In [[elder abuse]], important factors are stress due to the nature of the past relationship between the abused person and the care giver. | + | The second level focuses on '''close relationships''', such as those with family and friends. In youth violence, for example, having friends who engage in or encourage violence can increase a young person’s risk of being a victim or perpetrator of violence. For intimate partner violence, a consistent marker at this level of the model is marital conflict or discord in the relationship. In [[elder abuse]], important factors are stress due to the nature of the past relationship between the abused person and the care giver. |

| − | The third level explores the community | + | The third level explores the '''community context''': schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods. Risk at this level may be affected by factors such as the existence of a local drug trade, the absence of social networks, and concentrated poverty. All these factors have been shown to be important in several types of violence. |

| − | Finally, the fourth level looks at the broad societal factors that help to create a climate in which violence is encouraged or inhibited: the responsiveness of the criminal justice system, social and cultural norms regarding gender roles or parent-child relationships, income inequality, the strength of the social welfare system, the social acceptability of violence, the availability of weapons, the exposure to violence in mass media, and political instability. | + | Finally, the fourth level looks at the broad '''societal factors''' that help to create a climate in which violence is encouraged or inhibited: the responsiveness of the criminal justice system, social and cultural norms regarding gender roles or parent-child relationships, income inequality, the strength of the social welfare system, the social acceptability of violence, the availability of weapons, the exposure to violence in mass media, and political instability. |

=== Child-rearing === | === Child-rearing === | ||

| + | Cross-cultural studies have shown that greater prevalence of [[corporal punishment]] of children tends to predict higher levels of violence in societies. For instance, analysis of 186 [[pre-industrial society|pre-industrial societies]] found that corporal punishment was more prevalent in societies which also had higher rates of homicide, assault, and war.<ref>Carol R. Ember and Melvin Ember, Explaining Corporal Punishment of Children: A Cross-Cultural Study ''American Anthropologist'' 107(4) (2005): 609–619. </ref> In the United States, [[domestic corporal punishment]] has been linked to later violent acts against family members and spouses.<ref>Elizabeth T. Gershoff, [https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=258654 Report on Physical Punishment in the United States: What Research Tells Us About Its Effects on Children] Center for Effective Discipline, 2008. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | ||

| − | + | While studies showing associations between physical punishment of children and later [[aggression]] cannot prove that physical punishment causes an increase in aggression, a number of [[Longitudinal study|longitudinal studies]] suggest that the experience of physical punishment has a direct causal effect on later aggressive behaviors.<ref>Joan Durrant and Ron Ensom, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3447048/ Physical punishment of children: lessons from 20 years of research] ''Canadian Medical Association Journal'' 184(12) (2012):1373–1377. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | |

=== Psychology === | === Psychology === | ||

| + | The causes of violent behavior in people are often a topic of research in [[psychology]], where "violent behavior is defined as overt and intentional physically aggressive behavior against another person."<ref>Jan Volavka, [https://wayback.archive-it.org/all/20071127111237/http://neuro.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/reprint/11/3/307.pdf The Neurobiology of Violence, An Update] ''Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 11(3) (Summer 1999): 307-314. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Since violence is a matter of perception as well as a measurable phenomenon, psychologists have found variability in whether people perceive certain physical acts as "violent." For example, in a state where execution is a legalized punishment we do not typically perceive the executioner as "violent," though we may talk, in a more metaphorical way, of the state acting violently. Likewise, understandings of violence are linked to a perceived aggressor-victim relationship: hence psychologists have shown that people may not recognize defensive use of force as violent, even in cases where the amount of force used is significantly greater than in the original aggression.<ref>John Rowan, ''The Structured Crowd'' (Davis-Poynter, 1978, ISBN 070670164X).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Since violence is a matter of perception as well as a measurable phenomenon, psychologists have found variability in whether people perceive certain physical acts as "violent" | ||

| − | + | Whether violence is an inherent human trait has long been a contentious issue. Certainly, religious texts record violence within the first human family, when Cain killed his brother Abel out of anger and jealousy (Genesis 4:4-8). Among prehistoric humans, there is archaeological evidence for both contentions of violence and peacefulness as primary characteristics.<ref>Heather Whipps, [https://www.livescience.com/640-peace-war-early-humans-behaved.html Peace or War? How early humans behaved] ''Live Science'', March 16, 2006. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | + | The "violent male ape" image is often brought up in discussions of human violence, arguing that violence is inherent in human beings, particularly males, just as it is in non-human primates, although studies have also shown that not all primates are violent.<ref>Dale Peterson and Richard Wrangham, ''Demonic Males: Apes and the Origins of Human Violence'' (Mariner Books, 1997, ISBN 0395877431).</ref> |

| − | + | Evolutionary psychologists argue that humans have experienced an evolutionary history of violence, being similar to most [[mammal]] species and use violence in specific situations. Seven adaptive problems our ancestors recurrently faced have been proposed as being solved by aggression: "co-opting the resources of others, defending against attack, inflicting costs on same-sex rivals, negotiating status and hierarchies, deterring rivals from future aggression, deterring mate from infidelity, and reducing resources expended on genetically unrelated children."<ref>Aaron T. Goetz, [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/41138736_The_Evolutionary_Psychology_of_Violence The Evolutionary Psychology of Violence] ''Psicothema'' 22(1) (February 2010):15-21. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | + | Today, the use of violence often is a source of [[pride]] and a defense of [[honor]], especially among males who believe violence defines manhood.<ref>Leland R. Beaumont, [http://www.emotionalcompetency.com/violence.htm Violence] ''Emotional Competency''. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> Violent behavior may represent an effort to eliminate feelings of [[shame]] and [[humiliation]], and gain respect.<ref>James Gilligan, ''Preventing Violence'' (Thames & Hudson, 2001, ISBN 0500282781).</ref> | |

| − | + | Nevertheless, violent tendencies can be overcome in human society.<ref>William L. Ury (ed.), ''Must We Fight?: From the Battlefield to the Schoolyard-A New Perspective on Violent Conflict and Its Prevention'' (Jossey-Bass, 2002. ISBN 0787961035).</ref> In fact, "we can control our propensity for violence — however deep-rooted it may be — better than other primates can." <ref>Christopher Wanjek, [https://www.livescience.com/56306-primates-including-humans-are-the-most-violent-animals.html Primates, Including Humans, Are the Most Violent Animals] ''Live Science'', September 28, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> Again, the biblical record supports such a position, describing how the brothers [[Jacob]] and [[Esau]] were able to reconcile without violence (Genesis 33:4). In fact, throughout history, most religions, and religious individuals like [[Mahatma Gandhi]], have taught that humans are capable of eliminating individual violence and organizing societies through purely [[nonviolent]] means. | |

| − | In | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=== Targeted violence === | === Targeted violence === | ||

| + | Several rare but painful episodes of [[assassination]], attempted assassination and [[school shooting]]s at elementary, middle, high schools, as well as colleges and universities in the United States, led to a considerable body of research on ascertainable behaviors of persons who have planned or carried out such attacks. These studies (1995–2002) investigated what the authors called "targeted violence," described the "path to violence" of those who planned or carried out attacks and laid out suggestions for law enforcement and educators. A major point from these research studies is that targeted violence does not just "come out of the blue."<ref>Robert A. Fein, et al., ''Threat Assessment in Schools: A Guide the Managing Threatening Situations and to Creating Safe School Climates'' (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013, ISBN 1482696592). </ref> | ||

| − | + | === Media === | |

| + | Research into the [[media]] and violence examines whether links between consuming media violence and subsequent aggressive and violent behavior exists. Although some scholars had claimed media violence may increase aggression,<ref>Craig A. Anderson, et al., [https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1111/j.1529-1006.2003.pspi_1433.x The Influence of Media Violence on Youth] ''[Psychological Science in the Public Interest'' 4(3) (December 1, 2003):81–110. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> this view is coming increasingly in doubt both in the scholarly community<ref>Christopher J. Ferguson, [https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/gpr-14-2-68.pdf Blazing Angels or Resident Evil? Can Violent Video Games Be a Force for Good?] ''Review of General Psychology'' 14(2) (2010): 68–81. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> and was rejected by the [[United States Supreme Court|US Supreme Court]] in the ''[[Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association|Brown v EMA]]'' case.<ref>[https://www.oyez.org/cases/2010/08-1448 Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association] ''Oyez''. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=== Religion === | === Religion === | ||

| − | + | [[File:La masacre de San Bartolomé, por François Dubois.jpg|thumb|250px|The [[St. Bartholomew's Day massacre]] of French Protestants, 1572]] | |

| + | Religious and political ideologies have been the cause of interpersonal violence throughout history.<ref>Robert Jackson, [https://academic.oup.com/monist/article-abstract/89/2/274/1065691/?redirectedFrom=PDF "Doctrinal War: Religion and Ideology in International Conflict"] ''The Monist'' 89(2) (April 1, 2006): 274–300. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> Ideologues often falsely accuse others of violence, such as the ancient [[blood libel]] against [[Jews]], the [[medieval]] accusations of casting [[witchcraft]] spells against women, and modern accusations of [[satanic ritual abuse]] against [[day care]] center owners and others.<ref>[http://www.religioustolerance.org/ra_case.htm 43 M.V.M.O. Court Cases with Allegations of Multiple Sexual And Physical Abuse of Children] ''Religious Tolerance''. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | ||

| − | [[ | + | Both supporters and opponents of the twenty-first-century [[War on Terror]]ism regard it largely as an ideological and religious war.<ref>Richard A. Clarke, ''Against All Enemies: Inside America's War on Terror'' (Free Press, 2004, ISBN 9780743260459).</ref><ref>John L. Esposito, ''Unholy War: Terror in the Name of Islam'' (Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 0195168860).</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | === Geopolitical context === | |

| + | Place, space, and landscape, both geographical and political, are significant factors in the practice of organized violence historically and in the present.<ref>Derek Gregory and Allan Pred (eds.), ''Violent Geographies: Fear, Terror, and Political Violence'' (Routledge, 2006, ISBN 0415951461).</ref> In many cases the state plays a role in the use of violence: "modern states not only claim a monopoly of the legitimate means of violence; they also routinely use the threat of violence to enforce the rule of law."<ref name=Hyndman>Jennifer Hyndman, "Violence" in Derek Gregory, et al. (eds.), ''Dictionary of Human Geography'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, ISBN 9781405132886).</ref> Beyond the use of violence to enforce the law, cultural violence, in other words "any aspect of culture such as language, religion, ideology, art, or cosmology," may be used to legitimize structural violence.<ref name=Hyndman/> | ||

| − | + | The state, in the grip of a perceived, potential crisis (whether legitimate or not) may take preventative legal measures, such as a suspension of [[human rights]], in what can be referred to as a "state of exception."<ref name=Agamben> | |

| + | Giorgio Agamben, ''Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life'' (Stanford University Press, 1998, ISBN 0804732183).</ref> In such a climate the formation of [[concentration camp]]s, such as those organized by the [[Nazi Germany]] can occur. Here, the physical space of the camp "is a piece of land placed outside the normal juridical order, but it is nevertheless not simply an external space."<ref name=Agamben/> In that space people lose all rights as human beings, and can be treated with extreme violence since "no act committed against them could appear any longer as a crime."<ref name=Agamben/> | ||

| − | + | Another example state-sponsored violence is found in [[Cambodia]] in the 1970s. [[Genocide]] under the [[Khmer Rouge]] and [[Pol Pot]] resulted in the deaths of over two million Cambodians (which was 25 percent of the Cambodian population) in [[extermination camp]]s referred to as the "[[Killing Fields]]."<ref>Karen Christensen and David Levinson (eds.), ''Encyclopedia of Modern Asia'' (Charles Scribner's Sons, 2002, ISBN 0684806177).</ref> In these Killing Fields people were murdered with impunity in a display of structural violence. | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Prevention == | == Prevention == | ||

| + | The threat and enforcement of physical [[punishment]] has been a tried and tested method of preventing violence since civilization began. It is used in various degrees in most countries. | ||

| − | + | However, the authorized use of acts of physical violence to prevent violence is problematic when the situation is not one of clear and present danger. German political theorist [[Hannah Arendt]] noted that: | |

| + | <blockquote>Violence can be justifiable, but it never will be legitimate ... Its justification loses in plausibility the farther its intended end recedes into the future. No one questions the use of violence in self-defense, because the danger is not only clear but also present, and the end justifying the means is immediate.<ref>Hannah Arendt, ''On Violence'' (Mariner Books, 1970).</ref></blockquote> | ||

=== Interpersonal violence === | === Interpersonal violence === | ||

| − | A review of scientific literature by the [[World Health Organization]] on the effectiveness of strategies to prevent interpersonal violence identified | + | A review of scientific literature by the [[World Health Organization]] on the effectiveness of strategies to prevent interpersonal violence identified several strategies as being effective.<ref>[https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/4th_milestones_meeting/publications/en/ Violence Prevention: the evidence] World Health Organization. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> These strategies target risk factors at all four levels of the ecological model. |

==== Child–caregiver relationships ==== | ==== Child–caregiver relationships ==== | ||

| − | Among the most effective | + | Among the most effective programs to prevent [[child abuse]] and maltreatment and reduce childhood aggression are those that provide support and education to the caregivers. Examples of such programs are the Nurse Family Partnership home-visiting program and the Triple P (Positive Parenting Program). There is also emerging evidence that such programs reduce convictions and violent acts in adolescence and early adulthood, and probably help decrease intimate partner violence and self-directed violence in later life.<ref>David Olds, et al., [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9272895 Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect: 15 year follow-up of a randomized trial] ''Journal of the American Medical Association'' 278(8) (1997):637–643. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> |

==== Life skills in youth ==== | ==== Life skills in youth ==== | ||

| − | + | [[Life skills]] acquired in social development programs can reduce involvement in violence, improve social skills, boost educational achievement and improve job prospects. Life skills refer to social, emotional, and behavioral competencies which help children and adolescents effectively deal with the challenges of everyday life. | |

| − | + | Prevention programs shown to be effective or to have promise in reducing youth violence include life skills and social development programs designed to help children and adolescents manage anger, resolve [[conflict]], and develop the necessary social skills to solve problems; schools-based anti-bullying prevention programs; and programs to reduce access to alcohol, illegal drugs, and guns.<ref>[https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/4th_milestones_meeting/evidence_briefings_all.pdf "Violence prevention: the evidence"] ''World Health Organization'', 2010. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> Also, given significant neighborhood effects on youth violence, urban renewal projects such as [[business improvement district]]s have shown a reduction in youth violence.<ref>John MacDonald, et al., [https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2009/RAND_TR622.pdf "Neighborhood Effects on Crime and Youth Violence: The Role of Business Improvement Districts in Los Angeles"] ''Centers for Disease Control and Prevention'', 2009. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

==== Cultural norms ==== | ==== Cultural norms ==== | ||

| − | Rules or expectations of | + | Rules or expectations of behavior – norms – within a cultural or social group can encourage violence. Interventions that challenge cultural and [[social norms]] supportive of violence can prevent acts of violence. |

| + | |||

| + | Challenging social and cultural norms related to gender can reduce [[dating violence]] and [[sexual abuse]] among teenagers and young adults. For instance, programs that combine micro-finance with gender equity training can reduce intimate partner violence.<ref>J.C. Kim, et al., [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17761566 Understanding the impact of a microfinance-based intervention on women's empowerment and the reduction of intimate partner violence in South Africa] ''American Journal of Public Health'' 97(10) (2007): 1794–1802. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> School-based programs such as Safe Dates in the United States<ref>[https://www.crimesolutions.gov/ProgramDetails.aspx?ID=142 Program Profile: Safe Dates] ''National Institute of Justice'', June 4, 2011. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> and the Youth Relationship Project in Canada.<ref>[https://www.crimesolutions.gov/ProgramDetails.aspx?ID=467 Program Profile: Youth Relationships Project] ''National Institute of Justice'', May 16, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> have been found to be effective for reducing dating violence | ||

| − | ==== Support | + | ==== Support programs ==== |

| − | Interventions to identify victims of interpersonal violence and provide effective care and support are critical for protecting health and breaking cycles of violence from one generation to the next. Examples | + | Interventions to identify victims of interpersonal violence and provide effective care and support are critical for protecting health and breaking cycles of violence from one generation to the next. Examples of such interventions include: screening tools to identify victims of intimate partner violence and refer them to appropriate services; psycho-social interventions – such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy – to reduce mental health problems associated with violence, including post-traumatic stress disorder; and protection orders, which prohibit a perpetrator from contacting the victim, to reduce repeat victimization among victims of intimate partner violence. |

=== Collective violence === | === Collective violence === | ||

| − | + | Policies that facilitate reductions in [[poverty]], that make [[decision-making]] more accountable, that reduce inequalities between groups, as well as policies that reduce access to biological, chemical, nuclear, and other weapons are recommended to reduce collective violence.<ref name=Collective> World Health Organization, [https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/global_campaign/en/chap8.pdf?ua=1 Chapter 8: Collective violence] ''World report on violence and health''. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | |

| + | |||

| + | When planning responses to violent conflicts, recommended approaches include assessing at an early stage who is most vulnerable and what their needs are, co-ordination of activities between various players and working towards global, national and local capabilities so as to deliver effective health services during the various stages of an emergency.<ref name=Collective/> | ||

=== Criminal justice === | === Criminal justice === | ||

| − | One of the main functions of [[law]] is to regulate violence | + | One of the main functions of [[law]] is to regulate violence. [[Law enforcement]] is the main means of regulating nonmilitary violence in society. Governments regulate the use of violence through [[legal system]]s governing individuals and political authorities, including the [[police]] and [[military]]. Civil societies authorize some amount of violence to maintain the status quo and enforce laws. |

| − | + | The criminal justice approach sees its main task as enforcing laws that proscribe violence and ensuring that "justice is done" by ensuring that offenders are properly identified, that the degree of their guilt is as accurately ascertained as possible, and that they are punished appropriately. To prevent and respond to violence, the criminal justice approach relies primarily on deterrence, incarceration, and the punishment and rehabilitation of perpetrators. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In recent decades in many countries in the world, the criminal justice system has taken an increasing interest in preventing violence before it occurs. For instance, much of community and [[problem-oriented policing]] aims to reduce crime and violence by altering the conditions that foster it – and not to increase the number of arrests. Indeed, some police leaders have gone so far as to say the police should primarily be a crime prevention agency.<ref> William Bratton and Peter Knobler, ''The Turnaround: How America's Top Cop Reversed the Crime Epidemic'' (Random House, 1998, ISBN 9780679452515).</ref> Juvenile justice systems – an important component of criminal justice systems – are largely based on the belief in rehabilitation and prevention. In the US, the criminal justice system has, for instance, funded school- and community-based initiatives to reduce children's access to guns and teach conflict resolution. | |

| − | The | + | === Public health === |

| − | + | The global public health response to interpersonal violence began in earnest in the mid-1990s. In 1996, the World Health Assembly adopted Resolution WHA49.25 which declared violence "a leading worldwide public health problem" and requested that the World Health Organization (WHO) initiate public health activities to (1) document and characterize the burden of violence, (2) assess the effectiveness of programs, with particular attention to women and children and community-based initiatives, and (3) promote activities to tackle the problem at the international and national levels.<ref>[https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/resources/publications/en/WHA4925_eng.pdf "WHA49.25 Prevention of violence: a public health priority"] ''World Health Organization'', May 25, 1996. Retrieved June 19, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Rather than focusing on individuals, the public health approach aims to provide the maximum benefit for the largest number of people, and to extend better care and safety to entire populations. The public health approach considers that violence, rather than being the result of any single factor, is the outcome of multiple risk factors and causes, interacting at four levels of a nested hierarchy (individual, close relationship/family, community, and wider society) of the [[Social ecological model]]. Cooperative efforts from such diverse sectors as health, education, social welfare, and criminal justice are often necessary to solve what are usually assumed to be purely "criminal" or "medical" problems. | |

| − | + | There are several reasons why a public health approach is likely to be effective in preventing violence. First, the significant amount of time health care professionals dedicate to caring for victims and perpetrators of violence has made them familiar with the problem and has led many, particularly in emergency departments, to mobilize to address it. The information, resources, and infrastructures the health care sector has at its disposal are an important asset for research and prevention work. Second, the magnitude of the problem and its potentially severe lifelong consequences and high costs to individuals and wider society call for population-level interventions typical of the public health approach. Third, the criminal justice approach, the other main approach to addressing violence (link to entry above), has traditionally been more geared towards violence that occurs between male youths and adults in the street and other public places – which makes up the bulk of homicides in most countries – than towards violence occurring in private settings such as child maltreatment, intimate partner violence, and elder abuse – which makes up the largest share of non-fatal violence. Fourth, evidence is beginning to accumulate that a science-based public health approach is effective at preventing interpersonal violence. | |

| − | |||

From a public health perspective, prevention strategies can be classified into three types: | From a public health perspective, prevention strategies can be classified into three types: | ||

* Primary prevention – approaches that aim to prevent violence before it occurs. | * Primary prevention – approaches that aim to prevent violence before it occurs. | ||

| − | * Secondary prevention – approaches that focus on the more immediate responses to violence, such as pre-hospital care, emergency services or treatment for sexually transmitted infections following a rape. | + | * Secondary prevention – approaches that focus on the more immediate responses to violence, such as pre-hospital care, emergency services, or treatment for sexually transmitted infections following a [[rape]]. |

* Tertiary prevention – approaches that focus on long-term care in the wake of violence, such as rehabilitation and reintegration, and attempt to lessen trauma or reduce long-term disability associated with violence. | * Tertiary prevention – approaches that focus on long-term care in the wake of violence, such as rehabilitation and reintegration, and attempt to lessen trauma or reduce long-term disability associated with violence. | ||

| − | A public health approach emphasizes the primary prevention of violence, | + | A public health approach emphasizes the primary prevention of violence, stopping it from occurring in the first place. Perhaps the most critical element of a public health approach to prevention is the ability to identify underlying causes rather than focusing upon more visible symptoms. This allows for the development and testing of effective approaches to address the underlying causes and so improve health. |

| − | The | + | The approach involves the following four steps: |

# Defining the problem conceptually and numerically, using statistics that accurately describe the nature and scale of violence, the characteristics of those most affected, the geographical distribution of incidents, and the consequences of exposure to such violence. | # Defining the problem conceptually and numerically, using statistics that accurately describe the nature and scale of violence, the characteristics of those most affected, the geographical distribution of incidents, and the consequences of exposure to such violence. | ||

# Investigating why the problem occurs by determining its causes and correlates, the factors that increase or decrease the risk of its occurrence (risk and protective factors) and the factors that might be modifiable through intervention. | # Investigating why the problem occurs by determining its causes and correlates, the factors that increase or decrease the risk of its occurrence (risk and protective factors) and the factors that might be modifiable through intervention. | ||

| − | # Exploring ways to prevent the problem by using the above information and designing, monitoring and rigorously assessing the effectiveness of | + | # Exploring ways to prevent the problem by using the above information and designing, monitoring and rigorously assessing the effectiveness of programs through outcome evaluations. |

| − | # Disseminating information on the effectiveness of | + | # Disseminating information on the effectiveness of programs and increasing the scale of proven effective programs. Approaches to prevent violence, whether targeted at individuals or entire communities, must be properly evaluated for their effectiveness and the results shared. This step also includes adapting programs to local contexts and subjecting them to rigorous re-evaluation to ensure their effectiveness in the new setting. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=== Human rights === | === Human rights === | ||

| − | + | The [[human rights]] approach is based on the obligations of states to respect, protect and fulfill human rights and therefore to prevent, eradicate, and punish violence. It recognizes violence as a violation of many human rights: the rights to life, liberty, [[autonomy]], and security of the person; the rights to equality and non-discrimination; the rights to be free from [[torture]] and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment or punishment; the right to [[privacy]]; and the right to the highest attainable standard of [[health]]. | |

| − | The [[human rights]] approach is based on the obligations of states to respect, protect and fulfill human rights and therefore to prevent, eradicate and punish violence. It recognizes violence as a violation of many human rights: the rights to life, liberty, [[autonomy]] and security of the person; the rights to equality and non-discrimination; the rights to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment; the right to [[privacy]]; and the | ||

| − | + | These human rights are enshrined in [[international human rights law|international and regional treaties]] and national constitutions and laws, which stipulate the obligations of states, and include mechanisms to hold states accountable. The [[Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women]], for example, requires that countries party to the Convention take all appropriate steps to end violence against women. The [[Convention on the Rights of the Child]] in its Article 19 states that States Parties shall take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social, and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including [[child sexual abuse|sexual abuse]], while in the care of parent(s), legal guardian(s), or any other person who has the care of the child. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| Line 314: | Line 250: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

| + | * Agamben, Giorgio. ''Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life''. Stanford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0804732183 | ||

| + | * Arendt, Hannah. ''On Violence''. Mariner Books, 1970. | ||

* Barzilai, Gad. ''Communities and Law: Politics and Cultures of Legal Identities''. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2003. ISBN 0472113151 | * Barzilai, Gad. ''Communities and Law: Politics and Cultures of Legal Identities''. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2003. ISBN 0472113151 | ||

* Benjamin, Walter, and Giorgio Agamben. Brendan Moran and Carlo Salzani (eds.). ''Towards the Critique of Violence''. Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. ISBN 1474241891 | * Benjamin, Walter, and Giorgio Agamben. Brendan Moran and Carlo Salzani (eds.). ''Towards the Critique of Violence''. Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. ISBN 1474241891 | ||

| + | * Bratton, William, and Peter Knobler. ''The Turnaround: How America's Top Cop Reversed the Crime Epidemic''. Random House, 1998. ISBN 9780679452515 | ||

| + | * Christensen, Karen, and David Levinson (eds.). ''Encyclopedia of Modern Asia''. Charles Scribner's Sons, 2002. ISBN 0684806177 | ||

| + | * Clarke, Richard A. ''Against All Enemies: Inside America's War on Terror''. Free Press, 2004. ISBN 9780743260459 | ||

* Diamond, Jared M. ''Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies''. W. W. Norton & Company, 2005. ISBN 0393317552 | * Diamond, Jared M. ''Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies''. W. W. Norton & Company, 2005. ISBN 0393317552 | ||

* Diamond, Jared M. ''The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal''. Harper Perennial, 2006. ISBN 0060845503 | * Diamond, Jared M. ''The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal''. Harper Perennial, 2006. ISBN 0060845503 | ||

| + | * Esposito, John L. ''Unholy War: Terror in the Name of Islam''. Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0195168860 | ||

| + | * Fein, Robert A., et al. ''Threat Assessment in Schools: A Guide the Managing Threatening Situations and to Creating Safe School Climates''. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013. ISBN 1482696592 | ||

* Fry, Douglas P. (ed.). ''War, Peace, and Human Nature: The Convergence of Evolutionary and Cultural Views''. Oxford University Press, 2015. ISBN 0190232463 | * Fry, Douglas P. (ed.). ''War, Peace, and Human Nature: The Convergence of Evolutionary and Cultural Views''. Oxford University Press, 2015. ISBN 0190232463 | ||

| + | * Gilligan, James. ''Preventing Violence''. Thames & Hudson, 2001. ISBN 0500282781 | ||

| + | * Gregory, Derek, and Allan Pred (eds.). ''Violent Geographies: Fear, Terror, and Political Violence''. Routledge, 2006. ISBN 0415951461 | ||

| + | * Gregory, Derek, et al. (eds.). ''Dictionary of Human Geography''. Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. ISBN 9781405132886 | ||

* Guthrie, R. Dale. ''The Nature of Paleolithic Art''. University of Chicago Press, 2006. ISBN 0226311260 | * Guthrie, R. Dale. ''The Nature of Paleolithic Art''. University of Chicago Press, 2006. ISBN 0226311260 | ||

| + | * Jamison, Dean T., et al. (eds.). ''Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries''. World Bank Publications, 2006. ISBN 0821361791 | ||

| + | * Keeley, Lawrence H. ''War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage''. Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0195119126 | ||

| + | * Martin, Debra L., Ryan P. Harrod, and Ventura R. Pérez (eds.). ''The Bioarchaeology of Violence''. University Press of Florida, 2013. ISBN 0813049504 | ||

| + | * Peterson, Dale, and Richard Wrangham. ''Demonic Males: Apes and the Origins of Human Violence''. Mariner Books, 1997. ISBN 0395877431 | ||

| + | * Pinker, Steven. ''The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined''. Viking, 2011. ISBN 0670022950 | ||

| + | * Rowan, John. ''The Structured Crowd''. Davis-Poynter, 1978. ISBN 070670164X | ||

| + | * Ury, William L. (ed.). ''Must We Fight?: From the Battlefield to the Schoolyard-A New Perspective on Violent Conflict and Its Prevention''. Jossey-Bass, 2002. ISBN 0787961035 | ||

| + | * Van Der Kolk, Bessel. ''The Body Keeps The Score''. Penguin Books, 2015. ISBN 9780143127741 | ||

* Vazsonyi, Alexander T., Daniel J. Flannery, and Matt Delisi. ''The Cambridge Handbook of Violent Behavior and Aggression''. Cambridge University Press, 2018. ISBN 1316632210 | * Vazsonyi, Alexander T., Daniel J. Flannery, and Matt Delisi. ''The Cambridge Handbook of Violent Behavior and Aggression''. Cambridge University Press, 2018. ISBN 1316632210 | ||

| + | == External links == | ||

| + | All links retrieved May 3, 2023. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* [http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/en/ Violence prevention] at ''World Health Organization'' | * [http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/en/ Violence prevention] at ''World Health Organization'' | ||

* [https://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/index.html Violence prevention] at ''Centers for Disease Control and Prevention'' | * [https://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/index.html Violence prevention] at ''Centers for Disease Control and Prevention'' | ||

* [http://www.apa.org/pi/prevent-violence/index.aspx Violence prevention] at ''American Psychological Association'' | * [http://www.apa.org/pi/prevent-violence/index.aspx Violence prevention] at ''American Psychological Association'' | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Sociology]] | [[Category:Sociology]] | ||

{{Credits|Violence|913365507}} | {{Credits|Violence|913365507}} | ||

Latest revision as of 20:26, 3 May 2023