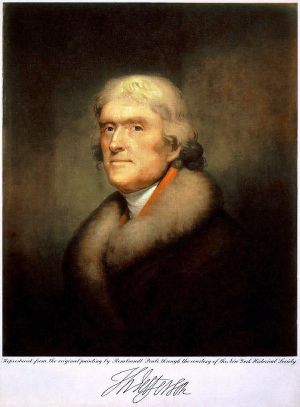

Thomas Jefferson

| Term of office | March 4, 1801 – March 3, 1809 |

| Preceded by | John Adams |

| Succeeded by | James Madison |

| Date of birth | April 13, 1743 |

| Place of birth | Shadwell, Virginia |

| Date of death | July 4, 1826 |

| Place of death | Charlottesville, Virginia |

| Spouse | Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was the third President of the United States (1801–1809), principal author of the Declaration of Independence (1776), and an influential Founding Father of the United States. Major events during his presidency include the Louisiana Purchase (1803), the Embargo Act of 1807, and the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806). Jefferson served as the second Governor of Virginia (1779–1781), first United States Secretary of State (1789–1793), and second Vice President (1797–1801).

In addition to his political career, Jefferson was an agriculturalist, horticulturist, architect, etymologist, archaeologist, mathematician, cryptographer, surveyor, paleontologist, author, lawyer, inventor, violinist, and the founder of the University of Virginia. Many people consider Jefferson to be among the most brilliant men ever to occupy the Presidency. President John F. Kennedy welcomed forty-nine Nobel Prize winners to the White House in 1962, saying, "I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone."[1]

Early life and education

Jefferson was born on April 2, 1743 according to the Julian calendar ("old style") used at the time, but under the Gregorian calendar ("new style") adopted during his lifetime, he was born on April 13. He was born into a prosperous Virginia family, the third of ten children (counting two who were stillborn). His mother was Jane Randolph, daughter of Isham Randolph, and a cousin of Peyton Randolph. Jefferson's father was Peter Jefferson, a planter and surveyor who owned a plantation in Albemarle County named Shadwell. Following a fire that burned down the family home at Shadwell, Peter Jefferson moved his family to Edge Hill, Virginia.

In 1752, Jefferson began attending a local school run by William Douglas, a Scottish reverend. At the age of nine, Jefferson began studying the classical languages of Latin and Greek as well as French. In 1757, when Jefferson was 14 years old, his father died. Jefferson inherited about 5,000 acres (20 km²) of land and dozens of slaves. He built his home there, which eventually became known as Monticello.

Jefferson entered the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg at the age of 16 and spent two years there, from 1760 to 1762. He studied mathematics, metaphysics, and philosophy under Professor William Small, who introduced the enthusiastic Jefferson to the writings of the British Empiricists, including John Locke, Francis Bacon, and Sir Isaac Newton (Jefferson would later refer to them as the "three greatest men the world had ever produced" [2]). At William and Mary, he reportedly studied 15 hours a day, perfected French, carried his Greek grammar book wherever he went, practiced the violin, and favored Tacitus and Homer.

In college, Jefferson was a member of the secret Flat Hat Club, from which the current William & Mary's daily student newspaper takes its name. After graduating in 1762 with highest honors, Jefferson studied law with his friend and mentor, George Wythe, and was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1767.

In 1772, Jefferson married a widow, Martha Wayles Skelton (1748-82). They had six children: Martha Jefferson Randolph (1772-1836), Jane Randolph (1774-1775), a stillborn or unnamed son (1777), Mary Wayles (1778-1804), Lucy Elizabeth (1780-1781), and a second Lucy Elizabeth (1782-1785). Martha Wayles Skelton died on September 6, 1782, and Jefferson never remarried. However, he is believed to have fathered several other children through his slave, Sally Hemmings. (see The Sally Hemings controversy below.)

Political career from 1774 to 1800

Jefferson practiced law and served in the Virginia House of Burgesses. In 1774, he wrote A Summary View of the Rights of British America, which was intended as instructions for the Virginia delegates to a national congress. The pamphlet was a powerful argument of American terms for a settlement with Britain. It helped speed the way to independence, and marked Jefferson as one of the most thoughtful patriot spokesmen.

As the colonists debated independence in 1776, Jefferson became the primary author of the Declaration of Independence. The Continental Congress delegated the task of writing the Declaration to a Committee of Five that in turn unanimously solicited Jefferson to prepare the draft of the Declaration alone. It was finally adopted and signed on July 4, 1776, marking what is known today as Independence Day.

In September 1776, Jefferson returned to Virginia and was elected to the new Virginia House of Delegates. During his term in the House, Jefferson set out to reform and update Virginia's system of laws to reflect its new status as a democratic state. He drafted 126 bills in three years, including laws to abolish primogeniture, establish freedom of religion, and streamline the judicial system. In 1778, Jefferson's "Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge" led to several academic reforms at his alma mater, including an elective system of study — the first in an American university.

Jefferson served as governor of Virginia from 1779-1781. As governor, he oversaw the transfer of the state capitol from Williamsburg to Richmond in 1780. He continued to advocate educational reforms at the College of William and Mary, including the nation's first student-policed honor code. In 1779, at Jefferson's behest, William and Mary appointed George Wythe to be the first professor of law in an American university. Dissatisfied with the rate of changes he wanted to push through, he would go on later in life to become the "father" and founder of the University of Virginia, which was the first university at which higher education was completely separate from religious doctrine.

From 1785–1789, Jefferson served as minister to France.Thus he did not attend the Constitutional Convention. He did generally support the new Constitution, although he thought the document flawed for lack of a Bill of Rights.

After returning from France, Jefferson served as the first Secretary of State under George Washington (1789–1793). Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton began sparring over national fiscal policy, specifically deficit spending in 1790. In further sparring with the Federalists, Jefferson came to equate Hamilton and the rest of the extreme Federalist as Tories. In the late 1790s, he worried that "Hamiltonianism" was taking hold. He equated this with "royalism." Jefferson strongly supported France against Britain when war broke out between those nations in 1793. When the Jay Treaty demostrated that Washington and Hamilton favored Britain, Jefferson retired to Monticello. He was elected Vice President (1797–1801), having placed second in a race against John Adams.

With a quasi-War with France underway (that is, an undeclared naval war), the Federalists under John Adams started a navy, built up the army, levied new taxes, readied for war and enacted the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798. Jefferson interpreted the Alien and Sedition Acts as an attack on his party more than on dangerous enemy aliens. He and Madison rallied support by anonymously writing the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions that declared that the Constitution only established an agreement between the central government and the states and that the federal government had no right to exercise powers not specifically delegated to it. Should the federal government assume such powers, its acts under them could be voided by a state. The Resolutions' importance lies in being the first statements of the states' rights theory that led to the later concepts of nullification and interposition.

Working closely with Aaron Burr of New York, Jefferson rallied his party, attacking the new taxes especially, and ran for the Presidency in 1800. Federalists counterattacked Jefferson, a Deist, as an atheist and enemy of Christianity. He tied with Burr for first place in the Electoral College, which left the House of Representatives to decide the election. After lengthy debate within the Federalist-controlled House, Hamilton convinced his party that Jefferson would be a lesser political evil than Burr. The issue was resolved by the House, on February 17, 1801, when Jefferson was elected President with Burr Vice President.

Presidency 1801-1809

Policies

Jefferson's Presidency, from 1801 to 1809, was the first to start and end in the White House; it was also the first Democratic-Republican Presidency. Jefferson is the only Vice President to later win an election and serve two full terms as President of the United States. Jefferson's term was marked by his belief in agrarianism, individual liberty, and limited government, sparking the development of a distinct American identity defined by republicanism.

The two great accomplishments of his first term were the Louisiana Purchase and commissioning of the Lewis and Clark Expedition during his first term. Jefferson was re-elected in the 1804 election. His second term was dominated by foreign policy concerns, as American neutrality was imperiled by war between Britain and France.

Jefferson was accused of compromising on his original principles during his Presidency. He strayed from the principles of keeping a small navy, agrarian economy, strict constructionism, and a small and weak government. A group called the tertium quids criticized Jefferson for his abandonment of his early principles.

In 1803, President Jefferson signed into law a bill that specifically excluded blacks from carrying the United States mail. Historian John Hope Franklin called the signing "a gratuitous expression of distrust of free Negroes who had done nothing to merit it." [3] Throughout his two terms, Jefferson did not once use his power of veto.[4]

Events during his Presidency

- First Barbary War (1801-1805)

- Louisiana Purchase (1803)

- Marbury v. Madison (1803)

- Creation of the Orleans Territory (1804)

- The Burr Conspiracy (1805)

- Land Act of 1804

- Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution is ratified (1804)

- Lewis and Clark expedition (1804-1806)

- Creation of the Louisiana Territory (later renamed the Missouri Territory) (1805)

- Tertium quids create a divide in the Democratic-Republican Party

- Embargo Act of 1807, an attempt to force respect for U.S. neutrality by ending trade with the belligerents in the Napoleonic War

- Abolition of the external slave trade (1808) [5]

States admitted to the Union

- Ohio – 1803

Father of a university

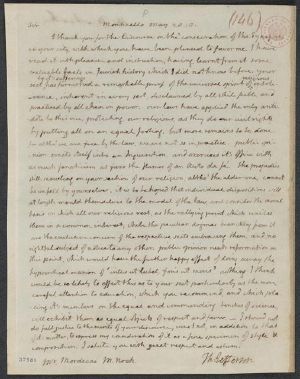

After leaving the Presidency, Jefferson continued to be active in public affairs. He also became increasingly obsessed with founding a new institution of higher learning, specifically one free of church influences where students could specialize in many new areas not offered at other universities. A letter to Joseph Priestley, in January 1800, indicated that he had been planning the university for decades before its establishment.

His dream was realized in 1819, with the founding of the University of Virginia. Upon its opening in 1825, it was then the first university to offer a full slate of elective courses to its students. One of the largest construction projects to that time in North America, it was notable for being centered about a library rather than a church. In fact, no campus chapel was included in his original plans. The university was designed as the capstone of the educational system of Virginia. In his vision, any citizen of the state could attend school with the sole criterion being ability. Until his death, he invited university students and faculty of the school to his home; Edgar Allan Poe was among them.

Jefferson's death

Jefferson died on the Fourth of July, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, the same day as John Adams' death. Deep in debt when he died, his possessions were sold at an auction on Monticello. In 1831, Jefferson's 552 acres (223 hect) were sold for $7,000 to James T. Barclay. In 1836, Barclay sold the estate and 218 acres (88 hect) of land to United States Navy Lieutenant Uriah P. Levy for $2,700. Levy then bought the surrounding land and started to purchase original furnishings. Lieutenant Levy is called "the Savior of Monticello" because of this. Levy died in 1862 as a result of the Civil War. In his will, he left the Monticello to the United States to be used as a school for orphans of navy officers. Thomas Jefferson is buried on his Monticello estate, in Charlottesville, Virginia. His epitaph, written by him with an insistence that only his words and "not a word more" be inscribed, reads:

|

Interests and activities

Jefferson was an accomplished architect who was extremely influential in bringing the Neo-Palladian style—popular among the Whig aristocracy of Britain—to the United States. The style was associated with Enlightenment ideas of republican civic virtue and political liberty. Jefferson designed his famous home, Monticello, near Charlottesville, Virginia; it included automatic doors, the first swivel chair, and other convenient devices invented by Jefferson. Nearby is the only university ever to have been founded by a President, the University of Virginia, of which the original curriculum and architecture Jefferson designed. Today, Monticello and the University of Virginia are together one of only four man-made World Heritage Sites in the United States of America. Jefferson is also credited with the architectural design of the Virginia State Capitol building, which was modeled after the Maison Carrée at Nîmes in southern France, an ancient Roman temple. Jefferson's buildings helped initiate the ensuing American fashion for Federal style architecture.

Jefferson's interests included archaeology, a discipline then in its infancy. He has sometimes been called the "father of archeology" in recognition of his role in developing excavation techniques. When exploring an Indian burial mound on his Virginia estate in 1784, Jefferson avoided the common practice of simply digging downwards until something turned up. Instead, he cut a wedge out of the mound so that he could walk into it, look at the layers of occupation, and draw conclusions from them.

Jefferson was an avid wine lover and noted gourmet. During his years in France (1784-1789) he took extensive trips through French and other European wine regions and sent the best back home. He is noted for the bold pronouncement: "We could in the United States make as great a variety of wines as are made in Europe, not exactly of the same kinds, but doubtless as good." While there were extensive vineyards planted at Monticello, a significant portion were of the European wine grape Vitis vinifera and did not survive the many vine diseases native to the Americas.

In 1812, he wrote A Manual of Parliamentary Practice that is still in use.

After the British burned Washington, D.C. and the Library of Congress in August 1814, Jefferson offered his own collection to the nation. In January 1815, Congress accepted his offer, appropriating $23,950 for his 6,487 books, and the foundation was laid for a great national library. Today, the Library of Congress' website for federal legislative information is named THOMAS, in honor of Jefferson.[1]

Political philosophy

A political philosopher who promoted classical liberalism, republicanism, and the separation of church and state, he was the author of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1779, 1786), which was the basis of the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. He was the eponym of Jeffersonian democracy and the founder and leader of the Democratic-Republican Party which dominated American politics for over a quarter-century. Although other American parties also have similarities of philosophy with Jefferson, the present Democratic Party is literally an offshoot of Jefferson's party, formed by Andrew Jackson and other prominent Democratic-Republicans (who by then included some ex-Federalists) in the 1820s.

Jefferson's vision for America was that of an agricultural nation of yeoman farmers minding their own affairs. It stood in contrast to the vision of Alexander Hamilton, who envisioned a nation of commerce and manufacturing. Jefferson was a great believer in the uniqueness and the potential of America and can be seen as the father of American exceptionalism. In particular, he was confident that an under-populated America could avoid what he considered the horrors of class-divided, industrialized Europe. Jefferson was influenced heavily by the ideas of many European Enlightenment thinkers. His political principles were heavily influenced by John Locke (particularly relating to the principles of inalienable rights and popular sovereignty) and Thomas Paine's Common Sense. Political theorists have also compared Jefferson's thought to that of his French contemporary, Jean-Jacques Rousseau. [6]

Jefferson believed that each individual has "certain inalienable rights." That is, these rights exist with or without government; man cannot create, take, or give them away. It is the right of "liberty" on which Jefferson is most notable for expounding. He defines it by saying "rightful liberty is unobstructed action according to our will within limits drawn around us by the equal rights of others. I do not add ‘within the limits of the law’, because law is often but the tyrant’s will, and always so when it violates the rights of the individual." [7] Hence, for Jefferson, though government cannot create a right to liberty, it can indeed violate it. And the limit of an individual's rightful liberty is not what law says it is but is simply a matter of stopping short of prohibiting other individuals from having the same liberty. A proper government, for Jefferson, is one that not only prohibits individuals in society from infringing on the liberty of other individuals, but also restrains itself from diminishing individual liberty.

Jefferson believed that individuals have an innate sense of morality that prescribes right from wrong when dealing with other individuals—that whether they choose to restrain themselves or not, they have an innate sense of the natural rights of others. He even believed that moral sense to be reliable enough that an anarchist society could function well, provided that it was reasonably small. On several occasions he expressed admiration for the non-government society of the Native Americans: [8]

Jefferson's dedication to "consent of the governed" was so thorough that he believed that individuals could not be morally bound by the actions of preceding generations. This included debts as well as law. He said that "no society can make a perpetual constitution or even a perpetual law. The earth belongs always to the living generation." He even calculated what he believed to be the proper cycle of legal revolution: "Every constitution then, and every law, naturally expires at the end of 19 years. If it is to be enforced longer, it is an act of force, and not of right." He arrived at 19 years through calculations with expectancy of life tables, taking into account what he believed to be the age of "maturity"—when an individual is able to reason for himself [9]. He also advocated that the National Debt should be eliminated. He did not believe that living individuals had a moral obligation to repay the debts of previous generations. He said that repaying such debts was "a question of generosity and not of right" [10].

Religious views

On matters of religion, Jefferson in 1800 was accused by his political opponents of being an atheist and enemy of religion. But Jefferson wrote at length on religion and most of his biographers agree he was a deist, a common position held by European intellectuals in the late 18th century. As Avery Cardinal Dulles, a leading Roman Catholic theologian reports, "In his college years at William and Mary he [Jefferson] came to admire Francis Bacon, Isaac Newton, and John Locke as three great paragons of wisdom. Under the influence of several professors he converted to the deist philosophy." [11] Dulles concludes:

In summary, then, Jefferson was a deist because he believed in one God, in divine providence, in the divine moral law, and in rewards and punishments after death; but did not believe in supernatural revelation. He was a Christian deist because he saw Christianity as the highest expression of natural religion and Jesus as an incomparably great moral teacher. He was not an orthodox Christian because he rejected, among other things, the doctrines that Jesus was the promised Messiah and the incarnate Son of God. Jefferson's religion is fairly typical of the American form of deism in his day.

Biographer Peterson summarizes Jefferson's theology:

First, that the Christianity of the churches was unreasonable, therefore unbelievable, but that stripped of priestly mystery, ritual, and dogma, reinterpreted in the light of historical evidence and human experience, and substituting the Newtonian cosmology for the discredited Biblical one, Christianity could be conformed to reason. Second, morality required no divine sanction or inspiration, no appeal beyond reason and nature, perhaps not even the hope of heaven or the fear of hell; and so the whole edifice of Christian revelation came tumbling to the ground. " [12]

Jefferson used deist terminology in repeatedly stating his belief in a creator, and in the United States Declaration of Independence used the terms "Creator", "Nature's God". Jefferson believed, furthermore, it was this Creator that endowed humanity with a number of inalienable rights, such as "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness". His experience in France just before the Revolution made him deeply suspicious of (Catholic) priests and bishops as a force for reaction and ignorance.

Jefferson was raised in the Church of England, at a time when it was the established church in Virginia and only denomination funded by Virginia tax money. Before the Revolution, Jefferson was a vestryman in his local church, a lay position that was part of political office at the time. Jefferson later expressed general agreement with his friend Joseph Priestley's Unitarianism. In a letter to a pioneer in Ohio he wrote, "I rejoice that in this blessed country of free inquiry and belief, which has surrendered its conscience to neither kings or priests, the genuine doctrine of only one God is reviving, and I trust that there is not a young man now living in the United States who will not die a Unitarian." [13]

Church and state

During the Revolution, Jefferson played a leading role in implementing the separation of church and state in Virginia. Previously the Anglican Church had tax support. As he wrote in his Notes on Virginia, a law was in effect in Virginia that "if a person brought up a Christian denies the being of a God, or the Trinity …he is punishable on the first offense by incapacity to hold any office …; on the second by a disability to sue, to take any gift or legacy …, and by three year' imprisonment." Prospective officer-holders, presumably including Jefferson, were required to swear that they did not believe in the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation. In 1779 Jefferson drafted "A Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom," and he regarded passage of this bill as a high achievement. For Jefferson, separation of church and state was not an abstract right but a necessary reform of the religious "tyranny" of one Christian sect over many other Christians.

Jefferson sought what he called a "wall of separation between Church and State", which he believed was a principle expressed by the First Amendment. This phrase has been cited several times by the Supreme Court in its interpretation of the Establishment Clause. [14] In an 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptist Association, he wrote:

"Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legislative powers of government reach actions only, and not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should "make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof," thus building a wall of separation between church and State" [15]

During his Presidency, Jefferson refused to issue proclamations calling for days of prayer and thanksgiving. Moreover, his private letters indicate he was skeptical of too much interference by clergy in matters of civil government. His letters contain the following observations: "History, I believe, furnishes no example of a priest-ridden people maintaining a free civil government" [16], and, "In every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty. He is always in alliance with the despot, abetting his abuses in return for protection to his own." [17] "May it be to the world, what I believe it will be, (to some parts sooner, to others later, but finally to all), the signal of arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self-government" [18]. Jefferson's harshest comments however, seemed to have been directed toward the spiritual descendants of John Calvin:

"The serious enemies are the priests of the different religious sects, to whose spells on the human mind it's improvement is ominous. Their pulpits are now resounding with denunciations against the appointment of Dr. Cooper whom they charge as Monarchist in opposition to their tritheism. Hostile as these sects are in every other point, to one another, they unite in maintaining their mystical theology against those who believe there is one God only. The Presbyterian clergy are the loudest. The most intolerant of all sects, the most tyrannical, and ambitious; ready at the word of the lawgiver, if such a word could be now obtained, to put the torch to the pile, and to rekindle in this virgin hemisphere, the flames in which their oracle Calvin consumed the poor Servetus ..."[19]

Jefferson and slavery

Jefferson's personal records show he owned more than 650 slaves over his lifetime[citation needed], some of whom were inherited from his parents and through his wife's parents. Some find it hypocritical that he owned slaves yet was outspoken in saying that slavery was immoral and on the course of eventual extinction. In 1801, after his election to the Presidency, Boston newspaper The New England Palladium said he had made his "ride into the temple of Liberty on the shoulders of slaves." [20]

In 1769, as a member of the House of Burgesses, Jefferson proposed for that body to emancipate slaves in Virginia, but he was unsuccessful [21]. In his first draft of the Declaration of Independence (1776), Jefferson condemned the British crown for sponsoring the importation of slavery to the colonies, charging that the crown "has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere." However, this language was dropped from the Declaration at the request of delegates from South Carolina and Georgia.

In 1778, the legislature passed a bill he proposed to ban further importation of slaves into Virginia; although this did not bring complete emancipation, in his words, it "stopped the increase of the evil by importation, leaving to future efforts its final eradication." In 1784, Jefferson's draft of what became the Northwest Ordinance stipulated that "there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude" in any of the new states admitted to the Union from the Northwest Territory [22]. Jefferson attacked the institution of slavery in his Notes on the State of Virginia (1784):

"There must doubtless be an unhappy influence on the manners of our people produced by the existence of slavery among us. The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other". [23]

Most of Jefferson's slaves were sold after his death to pay his many debts. During his lifetime, and in his will, Jefferson had freed only eight of his slaves (all of them members of the Hemings family) [24]. Edmund Bacon, the chief overseer of Monticello for twenty years, told his biographer that Jefferson's "orders to me were constant, that if there was any servant that could not be got along without the chastising that was customary, to dispose of him. He could not bear to have a servant whipped, no odds how much he deserved it."

Bacon also said he believed Jefferson would have freed all his slaves in his will, but was too far in debt. [25].

The Sally Hemings controversy

- For more details on this topic, see Sally Hemings and Jefferson DNA Data.

A subject of considerable controversy since Jefferson's time is whether he was the father of any of the children of his slave Sally Hemings. This allegation first gained widespread public attention in 1802, when journalist James T. Callender, wrote in a Richmond newspaper that Hemings had been Jefferson's "concubine" for many years, and had "several children" by her [26]. Jefferson never responded publicly about this issue. In his will, he freed Hemings' sons Madison and Eston, who later claimed that Jefferson was their father.

A 1998 DNA study concluded that there was a DNA link between some of Hemings descendants and the Jefferson family, but did not conclusively prove that Jefferson himself was their ancestor. Three studies were released in the early 2000s, following the publication of the DNA evidence. A study by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation [27] which runs Monticello states that "it is very unlikely that...any Jefferson other than Thomas Jefferson was the father of her children."

Monuments and memorials

- On April 13 1943, the 200th anniversary of Jefferson's birth, the Jefferson Memorial was dedicated in Washington, D.C. The memorial combines a low neo-classical saucer dome with a portico. The interior includes a 19 foot statue of Jefferson and engravings of passages from his writings. Most prominent are the words which are inscribed around the monument near the roof: "I have sworn upon the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man."

- Jefferson, together with George Washington, Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln, was chosen by President Calvin Coolidge to be depicted in stone at the Mount Rushmore Memorial.

- Jefferson's portrait appears on the U.S. $2 bill, nickel, and the $100 Series EE Savings Bond.

- The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Church (Unitarian Universalist) is located in Charlottesville, Virginia.

- On July 8, 2003, the NOAA ship Thomas Jefferson was commissioned in Norfolk, Virginia. This was done in commemoration of his establishment of a Survey of the Coast, the predecessor to NOAA's National Ocean Service.

Primary sources

- Thomas Jefferson: Writings: Autobiography / Notes on the State of Virginia / Public and Private Papers / Addresses / Letters (1984, ISBN 094045016X) The Library of America edition; see discussion of sources at [2]. There are numerous one-volume collections; this is perhaps the best place to start.

- Thomas Jefferson, Political Writings ed by Joyce Appleby and Terence Ball. Cambridge University Press. 1999

- Lipscomb, Andrew A. and Albert Ellery Bergh, eds. The Writings Of Thomas Jefferson 19 vol. (1907) not as complete nor as accurate as Boyd edition, but covers TJ from 1801 to his death. It is out of copyright, and so is online free.

- Edwin Morris Betts (editor), Thomas Jefferson's Farm Book, (Thomas Jefferson Memorial: December 1, 1953) ISBN 1882886100. Letters, notes, and drawings—a journal of plantation management that Jefferson left to posterity recording his contributions to scientific agriculture, including an experimental farm implementing innovations such as horizontal plowing and crop-rotation, and Jefferson's own moldboard plow. The Farm Book is a window to slave life, containing Jefferson's notes regarding the rations his overseer distributed, the daily tasks he required of particular slaves, and the number of yards he purchased for slaves' clothing. The book portrays the industries pursued by enslaved and free workmen, including in the blacksmith's shop and spinning and weaving house. Minutely detailed, the Farm Book is the most complete record of plantation activity in early America, casting light on the life of the Monticello plantation, its owner, and its inhabitants, both free and enslaved.

- Boyd, Julian P. et al, eds. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson. The definitive multivolume edition; available at major academic libraries. 31 volumes covers TJ to 1800, with 1801 due out in 2006. See description at [3]

- The Jefferson Cyclopedia (1900) large collection of TJ quotations arranged by 9000 topics; searchable; copyright has expired and it is online free.

- The Thomas Jefferson Papers, 1606-1827, 27,000 original manuscript documents at the Library of Congress. Online at [4]

- Jefferson, Thomas. Notes on the State of Virginia

- Adams, Dickinson W., ed. Jefferson's Extracts from the Gospels (1983). All three of Jefferson's versions of the Gospels, with relevant correspondence about his religious opinions. Valuable introduction by Eugene Sheridan.

- Bear, Jr., James A., ed. Jefferson's Memorandum Books, 2 vols. (1997). Jefferson's account books with records of daily expenses.

- Betts, Edwin Morris and James A. Bear, Jr., The Family Letters of Thomas Jefferson (1986). Correspondence of Jefferson with his children and grandchildren. Thomas Jefferson was never loved by his mother. Interesting

- Cappon, Lester J., ed. The Adams-Jefferson Letters (1959).

- Chinard, Gilbert, ed. The Commonplace Book of Thomas Jefferson: A Repertory of His Ideas on Government (1926). Jefferson's legal commonplace book.

- Howell, Wilbur Samuel, ed. Jefferson's Parliamentary Writings (1988). Jefferson's Manual of Parliamentary Practice, written when he was vice-President, with other relevant papers.

- Ledgin, Norm. 2000. "Diagnosing Jefferson: Evidence of a Condition That Guided His Beliefs, Behavior and Personal Associations"

- Shuffelton, Frank, ed. Notes on the State of Virginia (1999).

- Online, Notes on the State of Virginia [5]

- Smith, James Morton, ed. The Republic of Letters: The Correspondence between Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, 1776-1826, 3 vols. (1995).

- Wilson, Douglas L., ed. Jefferson's Literary Commonplace Book (1989).

External links and sources

- Works by Thomas Jefferson. Project Gutenberg

- Jefferson: Man of the Millennium

- American Revolution.com

- Quotations from Jefferson

- Thomas Jefferson Quotes at Liberty-Tree.ca

- Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Albert Ellery Bergh, ed., 19 vol. (1905). 5145KB zipped ASCII file

- Selected letters

- Biography on White House website

- Thomas Jefferson Biography

- University of Virginia biography

- The Papers of Thomas Jefferson at the Avalon Project (includes Inaugural Addresses, State of the Union Addresses, and other material)

- Library of Congress: Jefferson timeline

- Library of Congress: Jefferson exhibition

- "The Hobby of My Old Age": Jefferson's University of Virginia

- B. L. Rayner's 1829 Life of Thomas Jefferson, an on-line etext

- Thomas Jefferson's Liberal Anticapitalism by Claudio J. Katz

- NPR's The Thomas Jefferson Hour hosted by Clay S. Jenkinson

- Thomas Jefferson at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Thomas Jefferson at Find-A-Grave

- Medical History and Health of Thomas Jefferson

- Online Bio

- Monticello - Home of Thomas Jefferson

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Simpson's Contemporary Quotations, 1988, from Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: John F. Kennedy, 1962, p. 347

- ↑ Merrill D. Peterson, Thomas Jefferson: Writings, p. 1236

- ↑ [John Hope Franklin, Race and History: Selected Essays 1938-1988 (Louisiana State University Press: 1989) p. 336] and [John Hope Franklin, Racial Equality in America (Chicago: 1976), p. 24-26]

- ↑ http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0801767.html

- ↑ Abolition of the Atlantic Slave Trade in the United States

- ↑ J. G. A. Pocock, The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975), 533; see also Richard K. Matthews, The Radical Politics of Thomas Jefferson, (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1986), p. 17, 139n.16.

- ↑ Letter to Isaac H. Tiffany, 1819

- ↑ Notes on Virginia

- ↑ Letter to James Madison, 6 September 1789

- ↑ Letter to James Madison, 6 Sep 1789

- ↑ , Avery Cardinal Dulles, "The Deist Minimum" First Things: A Monthly Journal of Religion and Public Life Issue: 149. (Jan 2005) pp 25+

- ↑ Peterson 1975 p 50-51

- ↑ Letter to Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse June 26 1822

- ↑ Reynolds (98 U.S. at 164, 1879); Everson (330 U.S. at 59, 1947); McCollum (333 U.S. at 232, 1948)

- ↑ Letter to Danbury Baptist Association, CT, January 1, 1802

- ↑ Letter to Alexander von Humboldt, December 6, 1813

- ↑ Letter to Horatio G. Spafford, March 17, 1814

- ↑ Letter to Roger C. Weightman June 24, 1826

- ↑ Letter to William Short, April 13 1820

- ↑ Garry Wills. Negro President: Jefferson and the Slave Power, Houghton Mifflin, 2003.

- ↑ The Works of Thomas Jefferson in Twelve Volumes at the Library of Congress.

- ↑ Ordinance of 1787 Lalor Cyclopædia of Political Science

- ↑ Notes on the State of Virginia, Ch 18.

- ↑ Finkelman, Paul, Slavery and the Founders pp. 105, 107, 129.

- ↑ Mr Jefferson's Servants by Captain Edmund Bacon.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: A Brief Account

- ↑ Report of the Research Committee on Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings