Difference between revisions of "Sphinx" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

After the [[necropolis]] was abandoned, the Sphinx became buried up to its shoulders in sand. The first attempt to dig it out dates back to 1400 b.v.e., when the young [[Thutmose IV|Tutmosis IV]] formed an excavation party which, after much effort, managed to dig the front paws out. Tutmosis IV had a [[granite]] [[Stele|stela]] known as the "Dream Stela" placed between the paws. The stela reads, in part: | After the [[necropolis]] was abandoned, the Sphinx became buried up to its shoulders in sand. The first attempt to dig it out dates back to 1400 b.v.e., when the young [[Thutmose IV|Tutmosis IV]] formed an excavation party which, after much effort, managed to dig the front paws out. Tutmosis IV had a [[granite]] [[Stele|stela]] known as the "Dream Stela" placed between the paws. The stela reads, in part: | ||

| − | <blockquote>...the royal son, Thothmos, being arrived, while walking at midday and seating himself under the shadow of this mighty god, was overcome by slumber and slept at the very moment when Ra is at the summit (of heaven). He found that the Majesty of this august god spoke to him with his own mouth, as a father speaks to his son, saying: Look upon me, contemplate me, O my son Thothmos; I am thy father, Harmakhis-Khopri-Ra-Tum; I bestow upon thee the sovereignty over my domain, the supremacy over the living ... Behold my actual condition that thou mayest protect all my perfect limbs. The sand of the desert whereon I am laid has covered me. Save me, causing all that is in my heart to be executed.<ref> | + | <blockquote>...the royal son, Thothmos, being arrived, while walking at midday and seating himself under the shadow of this mighty god, was overcome by slumber and slept at the very moment when Ra is at the summit (of heaven). He found that the Majesty of this august god spoke to him with his own mouth, as a father speaks to his son, saying: Look upon me, contemplate me, O my son Thothmos; I am thy father, Harmakhis-Khopri-Ra-Tum; I bestow upon thee the sovereignty over my domain, the supremacy over the living ... Behold my actual condition that thou mayest protect all my perfect limbs. The sand of the desert whereon I am laid has covered me. Save me, causing all that is in my heart to be executed.<ref>Mallet, D. [http://www.harmakhis.org/The%20Stele%20of%20Thotmes%20IV%20%28Translation%29.htm Translation]. Retrieved February 22, 20007.</ref></blockquote> |

[[Ramesses II]] may have also performed restoration work on the Sphinx. | [[Ramesses II]] may have also performed restoration work on the Sphinx. | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

The inscription on a [[stele]] in the Great Sphinx dates it from one thousand years after the carving of the Sphinx, and gives three names of the sun: ''Kheperi - Re - Atum''. The [[Arabic]] name of the Great Sphinx, ''Abu al-Hôl'', translates as "Father of Terror". The Greek name "Sphinx" was applied to it in antiquity. But it has the head of a man, not of a woman. | The inscription on a [[stele]] in the Great Sphinx dates it from one thousand years after the carving of the Sphinx, and gives three names of the sun: ''Kheperi - Re - Atum''. The [[Arabic]] name of the Great Sphinx, ''Abu al-Hôl'', translates as "Father of Terror". The Greek name "Sphinx" was applied to it in antiquity. But it has the head of a man, not of a woman. | ||

| − | The Great Sphinx was believed to stand as a guardian of the Giza Plateau, where it faces the rising sun. It was the focus of solar worship in the Old Kingdom, centered in the adjoining temples built around the time of its probable construction. Its animal form, the lion, has long been a symbol associated with the sun in ancient Near Eastern civilizations. Images depicting the Egyptian king in the form of a lion smiting his enemies appear as far back as the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt. The sphinx of Giza is an ancient iconic mythical creature usually comprised of a recumbent lion—animal with sacred solar associations—with a human head, usually that of a pharaoh, probably that of [[Khafre]].<ref> Winston, Allen | + | The Great Sphinx was believed to stand as a guardian of the Giza Plateau, where it faces the rising sun. It was the focus of solar worship in the Old Kingdom, centered in the adjoining temples built around the time of its probable construction. Its animal form, the lion, has long been a symbol associated with the sun in ancient Near Eastern civilizations. Images depicting the Egyptian king in the form of a lion smiting his enemies appear as far back as the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt. The sphinx of Giza is an ancient iconic mythical creature usually comprised of a recumbent lion—animal with sacred solar associations—with a human head, usually that of a pharaoh, probably that of [[Khafre]].<ref> Winston, Allen. 2003. [http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/sphinx1.htm "The Great Sphinx of Giza: An Introduction"] Retrieved January 23, 2007. </ref> |

During the New Kingdom, the Sphinx became more specifically associated with the god ''Hor-em-akhet'' ([[Ancient Greek|Greek]] ''Harmachis'') or Horus at the Horizon, which represented the Pharaoh in his role as the ''Shesep ankh'' of Atum (living image of Atum). A temple was built to the northeast of the Sphinx by King [[Amenhotep II]], nearly a thousand years after its construction, dedicated to the cult of Horemakhet. | During the New Kingdom, the Sphinx became more specifically associated with the god ''Hor-em-akhet'' ([[Ancient Greek|Greek]] ''Harmachis'') or Horus at the Horizon, which represented the Pharaoh in his role as the ''Shesep ankh'' of Atum (living image of Atum). A temple was built to the northeast of the Sphinx by King [[Amenhotep II]], nearly a thousand years after its construction, dedicated to the cult of Horemakhet. | ||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

While it is more than likely that the Greeks acquired the idea of the sphinx through cultural diffusion, they nonetheless incorporated it to a large degree into their written mythology and gave it its name (a potential combination of the Greek verb σφινγω — ''sphingo'', meaning "to strangle" and the name Φιξ — ''Phix''. | While it is more than likely that the Greeks acquired the idea of the sphinx through cultural diffusion, they nonetheless incorporated it to a large degree into their written mythology and gave it its name (a potential combination of the Greek verb σφινγω — ''sphingo'', meaning "to strangle" and the name Φιξ — ''Phix''. | ||

| − | There was a single Sphinx in [[Greek mythology]], a unique demon of destruction and bad luck, according to [[Hesiod]] a daughter of [[Echidna (mythology)|Echidna]] and of [[Orthrus]] or, according to others, of [[Typhon]] and Echidna. She was represented in vase-painting and bas-reliefs most often seated upright rather than recumbent, as [[Hera]] or [[Ares]] sent the Sphinx from her [[Ethiopia]]n homeland (the Greeks remembered the Sphinx's foreign origin) to [[Thebes]], where she guarded the entrance to the city, asking all those who passed her famous riddle "Which creature in the morning goes on four feet, at noon on two, and in the evening upon three?" All those who answered wrong were killed, and it was not until [[Oedipus]] came along and solved the riddle that the besieged city was liberated, making Oedipus King and setting the background for his mythical fall from grace (the answer to the riddle is man; a baby crawls when young, walks on two legs as an adult, and uses a cane in old age).<ref> Hamilton, Edith. 1942. ''Mythology''. New York, NY: Little Brown.</ref> Bested at last, the Sphinx then threw herself from her high rock and died. An alternative version tells that she devoured herself. The exact riddle asked by the Sphinx was not specified by early tellers of the story and was not standardized as the one given above until much later in Greek history. Thus Oedipus can be recognized as a liminal or "threshold" figure, helping effect the transition between the old religious practices, represented by the Sphinx, and new, Olympian ones. | + | There was a single Sphinx in [[Greek mythology]], a unique demon of destruction and bad luck, according to [[Hesiod]] a daughter of [[Echidna (mythology)|Echidna]] and of [[Orthrus]] or, according to others, of [[Typhon]] and Echidna. She was represented in vase-painting and bas-reliefs most often seated upright rather than recumbent, as [[Hera]] or [[Ares]] sent the Sphinx from her [[Ethiopia]]n homeland (the Greeks remembered the Sphinx's foreign origin) to [[Thebes]], where she guarded the entrance to the city, asking all those who passed her famous riddle "Which creature in the morning goes on four feet, at noon on two, and in the evening upon three?" All those who answered wrong were killed, and it was not until [[Oedipus]] came along and solved the riddle that the besieged city was liberated, making Oedipus King and setting the background for his mythical fall from grace (the answer to the riddle is man; a baby crawls when young, walks on two legs as an adult, and uses a cane in old age).<ref> Hamilton, Edith. 1942. ''Mythology''. New York, NY: Little Brown. ISBN 0316341517</ref> Bested at last, the Sphinx then threw herself from her high rock and died. An alternative version tells that she devoured herself. The exact riddle asked by the Sphinx was not specified by early tellers of the story and was not standardized as the one given above until much later in Greek history. Thus Oedipus can be recognized as a liminal or "threshold" figure, helping effect the transition between the old religious practices, represented by the Sphinx, and new, Olympian ones. |

== Sphinx in South and South-East Asia == | == Sphinx in South and South-East Asia == | ||

| − | In contrast to the sphinx in [[ancient Egypt|Egypt]], [[Mesopotamia]], and [[ancient Greece|Greece]], where the traditions have been largely lost due to the discontinuity of the civilization,<ref> | + | In contrast to the sphinx in [[ancient Egypt|Egypt]], [[Mesopotamia]], and [[ancient Greece|Greece]], where the traditions have been largely lost due to the discontinuity of the civilization,<ref>Demisch, Heinz. 1977. Die Sphinx. ''Geschichte ihrer Darstellung von den Anfangen bis zur Gegenwart.'' </ref> the traditions of the "Asian sphinx" are still very much alive. The earliest artistic depictions of "sphinxes" from the South Asian subcontinent are to some extend influenced by Hellenistic art. But the "sphinxes" from Mathura, Kausambi, and Sanchi, dated to the third century B.C.E. till the first century C.E., also show a considerable non-Hellenist, indigenous character. It is therefore not possible to conclude the concept of the "sphinx" originated through foreign influence.<ref>[http://www.geocities.com/sphinxofindia/earlyart.html The Sphinx in Early Indian Art] Retrieved February 9, 2007.</ref>. |

[[Image:Purushamrigatribhuvanai01.JPG|thumb|left|200px|Purushamriga or Indian sphinx depicted on the Shri Varadaraja Perumal temple in Tribhuvana, India]] | [[Image:Purushamrigatribhuvanai01.JPG|thumb|left|200px|Purushamriga or Indian sphinx depicted on the Shri Varadaraja Perumal temple in Tribhuvana, India]] | ||

| − | In South [[India]] the "sphinx" is known as ''purushamriga'' ([[Sanskrit]]) or ''purushamirukam'' ([[Tamil]], meaning human-beast). It is found depicted in sculptural art in temples and palaces where it serves an apotropiac purpose, just like the "sphinxes" in other parts of the ancient world.<ref> | + | In South [[India]] the "sphinx" is known as ''purushamriga'' ([[Sanskrit]]) or ''purushamirukam'' ([[Tamil]], meaning human-beast). It is found depicted in sculptural art in temples and palaces where it serves an apotropiac purpose, just like the "sphinxes" in other parts of the ancient world.<ref>Demisch, Heinz. 1977. Die Sphinx. ''Geschichte ihrer Darstellung von den Anfangen bis zur Gegenwart.''</ref> According to tradition, it is said to take away the [[sin]]s of the devotees when they enter a temple and to ward off evil in general. It is therefore often found in a strategic position on the ''gopuram'' or temple gateway, or near the entrance of the ''Sanctum Sanctorum''. |

The ''purushamriga'' plays a significant role in daily as well as yearly [[ritual]]s of South Indian [[Hinduism|Shaiva]] temples. In the ''sodasa-upacara'' (or 16 honors) ritual, performed between one to six times at significant sacred moments throughout the day, it decorates one of the lamps of the ''diparadhana'' or lamp ceremony. And in several temples the ''purushamriga'' is also one of the ''vahana'', or vehicles of the deity during the processions of the ''Brahmotsava'' or festival. | The ''purushamriga'' plays a significant role in daily as well as yearly [[ritual]]s of South Indian [[Hinduism|Shaiva]] temples. In the ''sodasa-upacara'' (or 16 honors) ritual, performed between one to six times at significant sacred moments throughout the day, it decorates one of the lamps of the ''diparadhana'' or lamp ceremony. And in several temples the ''purushamriga'' is also one of the ''vahana'', or vehicles of the deity during the processions of the ''Brahmotsava'' or festival. | ||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

==Artistic Representations== | ==Artistic Representations== | ||

[[Image:Oedipus And The Sphinx - Project Gutenberg eText 14994.png|thumb|left|300 px| Oedipus and the Sphinx]] | [[Image:Oedipus And The Sphinx - Project Gutenberg eText 14994.png|thumb|left|300 px| Oedipus and the Sphinx]] | ||

| − | Beyond the monuments in Egypt, the sphinx has been depicted in [[art]] for centuries. Some of the most famous depictions, ranging from [[ancient Greece]] to [[Asia]], are variations of [[Odeipus]]' encounter with the sphinx. Some depictions show a sphinx in a position of power and wisdom, looking down on Oedipus as he tries to solve the riddle, while others depict the battle of minds as an epic, mortal fight.<ref> | + | Beyond the monuments in Egypt, the sphinx has been depicted in [[art]] for centuries. Some of the most famous depictions, ranging from [[ancient Greece]] to [[Asia]], are variations of [[Odeipus]]' encounter with the sphinx. Some depictions show a sphinx in a position of power and wisdom, looking down on Oedipus as he tries to solve the riddle, while others depict the battle of minds as an epic, mortal fight.<ref> 2007. [http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9069103 "Sphinx".] ''Encyclopedia Britannica''. Retrieved January 23, 2007.</ref> In any case, the artistic iconography of the Greek legend represents man's ability to penetrate the mysteries of the world, to use his mind in epic measures. |

The revived ''Mannerist Sphinx'' of the sixteenth century is sometimes thought of as the ''French Sphinx''. Her lovely coiffed head is erect and she has the pretty bust of a young woman. Often she wears [[pearl]]s. Her body is naturalistically rendered as a recumbent [[lion]]. Such Sphinxes were revived when the ''grottesche'' or "grotesque" decorations of the unearthed "Golden House" (''Domus Aurea'') of [[Nero]] were brought to light in late fifteenth century [[ancient Rome|Rome]], and she was incorporated into the classical vocabulary of [[arabesque]] designs that was spread throughout [[Europe]] in [[engraving]]s during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Her first appearances in French art are in the School of Fontainebleau in the 1520s and 1530s; her last appearances are in the [[Baroque|Late Baroque]] style of the French [[Régence]] (1715–1723). | The revived ''Mannerist Sphinx'' of the sixteenth century is sometimes thought of as the ''French Sphinx''. Her lovely coiffed head is erect and she has the pretty bust of a young woman. Often she wears [[pearl]]s. Her body is naturalistically rendered as a recumbent [[lion]]. Such Sphinxes were revived when the ''grottesche'' or "grotesque" decorations of the unearthed "Golden House" (''Domus Aurea'') of [[Nero]] were brought to light in late fifteenth century [[ancient Rome|Rome]], and she was incorporated into the classical vocabulary of [[arabesque]] designs that was spread throughout [[Europe]] in [[engraving]]s during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Her first appearances in French art are in the School of Fontainebleau in the 1520s and 1530s; her last appearances are in the [[Baroque|Late Baroque]] style of the French [[Régence]] (1715–1723). | ||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * Hamilton, Edith. | + | * Hamilton, Edith. 1998. (original 1942). ''Mythology''. Back Bay Books. ISBN 0316341517 |

| − | * Hancock, Graham | + | * Hancock, Graham & Robert Bauval. 1997. ''The Message of the Sphinx: A Quest for the Hidden Legacy of Mankind''. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0517888521 |

* Regier, Willis Goth. 2005. ''Book of the Sphinx''. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0750938617 | * Regier, Willis Goth. 2005. ''Book of the Sphinx''. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0750938617 | ||

* Zivie-Coche, Christiane. 2004. ''Sphinx: History Of A Monument ''. Ithica NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801489547 | * Zivie-Coche, Christiane. 2004. ''Sphinx: History Of A Monument ''. Ithica NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801489547 | ||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | *[http:// | + | *[http://al-eman.com/Islamlib/viewchp.asp?BID=224&CID=1 Al Maqrizi's account in Arabic] |

*[http://www.thehallofmaat.com/modules.php?name=Articles&file=article&sid=93 An academic article arguing the case for water erosion evidence] | *[http://www.thehallofmaat.com/modules.php?name=Articles&file=article&sid=93 An academic article arguing the case for water erosion evidence] | ||

*[http://www.eridu.co.uk/Author/egypt/lost.html Egypt—The Lost Civilization Theory] | *[http://www.eridu.co.uk/Author/egypt/lost.html Egypt—The Lost Civilization Theory] | ||

| + | *[http://www.users.globalnet.co.uk/~loxias/sphinx.htm/ Oedipus & the Sphinx] The Classics Pages | ||

*[http://www.wikimapia.org/#y=29975274&x=31137585&z=18&l=0&m=s Satellite images of Great Sphinx of Giza] at WikiMapia | *[http://www.wikimapia.org/#y=29975274&x=31137585&z=18&l=0&m=s Satellite images of Great Sphinx of Giza] at WikiMapia | ||

| + | *[http://guardians.net/egypt/sphinx/ Sphinx photo gallery] | ||

*[http://www.catchpenny.org/nose.html The Sphinx's Nose] | *[http://www.catchpenny.org/nose.html The Sphinx's Nose] | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

{{Credit2|Sphinx|105122524|Great_Sphinx_of_Giza|98331962|}} | {{Credit2|Sphinx|105122524|Great_Sphinx_of_Giza|98331962|}} | ||

Revision as of 06:31, 22 February 2007

The sphinx has had a long history of secrecy and intrigue, being viewed by many cultures as guardians of knowledge and speaking in riddles. While originating in Ancient Egypt, the sphinx as a mythical creature existed in Ancient Greece and Mesopotamia, was revered by the later Western World and to this day still exists in Eastern cultures.

Description

The Sphinx varies in physical features, but is almost always a conglomerate of two or more animals. In ancient Egypt there are three distinct types of sphinx: The Androsphinx, with the body of a lion and head of person; a Criosphinx, body of a lion with the head of ram; and Hierocosphinx, that had a body of a lion with a head of a falcon or hawk. In Greek mythology there is less variation: a winged lion with a woman's head, or a woman with the paws, claws, and breasts of a lion, a serpent's tail and eagle wings.

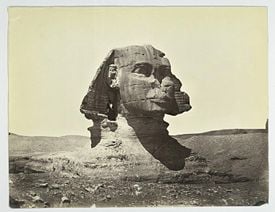

Egyptian sphinx

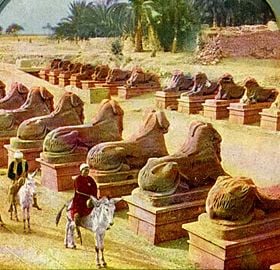

The sphinxes of ancient Egypt were regarded as iconic images. Usually, the Sphinxes appeared as giant statues with the faces of Pharaohs and almost always were regarded as protectors of temples or sacred areas. To what extent the sphinx played a role in ancient Egyptian mythology is an issue of debate. While the sphinx is not the only combination of animal and man to emerge in the religious art of the time, it may be one of the first, pre-dating all other anthropomorphic images of animal deities. The most famous and largest of sphinxes, "Seshepus," the Great Sphinx of Giza was originally dated to around the fourth century, but recent developments have raised the possibility that the sphinx might go back all the way to before the Old Kingdom. Other famous Egyptian sphinxes include the alabaster sphinx of Memphis, localized within the open-air museum at that site; and the ram-headed sphinxes (in Greek, criosphinxes) representing the god Amon, in Thebes, of which there were originally some nine hundred.

The largest and most famous Egyptian sphinx is Sesheps, the "Great Sphinx of Giza," situated on the Giza Plateau on the west bank of the Nile River, facing due east, with a small temple between its paws. The face of the Great Sphinx is believed to be the head of the pharaoh Khafra (often known by the Greek version of his name, Chephren) or possibly that of his brother, the Pharaoh Djedefra, which would date its construction from the fourth dynasty (2723 B.C.E. – 2563 B.C.E.). However, there are some alternative theories that re-date the Sphinx to the pre-Old Kingdom – and, according to one hypothesis, to prehistoric times.

The Great Sphinx is a statue with the face of a man and the body of a lion. Carved out of the surrounding limestone bedrock, it is 57 metres (260 feet) long, 6 m (20 ft) wide, and has a height of 20 m (65 ft), making it the largest single-stone statue in the world. Blocks of stone weighing upwards of 200 tons were quarried in the construction phase to build the adjoining Sphinx Temple. It is located on the west bank of the Nile River within the confines of the Giza pyramid field. The Great Sphinx faces due east, with a small temple between its paws.

After the necropolis was abandoned, the Sphinx became buried up to its shoulders in sand. The first attempt to dig it out dates back to 1400 b.v.e., when the young Tutmosis IV formed an excavation party which, after much effort, managed to dig the front paws out. Tutmosis IV had a granite stela known as the "Dream Stela" placed between the paws. The stela reads, in part:

...the royal son, Thothmos, being arrived, while walking at midday and seating himself under the shadow of this mighty god, was overcome by slumber and slept at the very moment when Ra is at the summit (of heaven). He found that the Majesty of this august god spoke to him with his own mouth, as a father speaks to his son, saying: Look upon me, contemplate me, O my son Thothmos; I am thy father, Harmakhis-Khopri-Ra-Tum; I bestow upon thee the sovereignty over my domain, the supremacy over the living ... Behold my actual condition that thou mayest protect all my perfect limbs. The sand of the desert whereon I am laid has covered me. Save me, causing all that is in my heart to be executed.[1]

Ramesses II may have also performed restoration work on the Sphinx.

It was in 1817 that the first modern dig, undertaken by Giovanni Battista Caviglia, uncovered the Sphinx's chest completely. The entirety of the Sphinx was finally dug out in 1925.

The inscription on a stele in the Great Sphinx dates it from one thousand years after the carving of the Sphinx, and gives three names of the sun: Kheperi - Re - Atum. The Arabic name of the Great Sphinx, Abu al-Hôl, translates as "Father of Terror". The Greek name "Sphinx" was applied to it in antiquity. But it has the head of a man, not of a woman.

The Great Sphinx was believed to stand as a guardian of the Giza Plateau, where it faces the rising sun. It was the focus of solar worship in the Old Kingdom, centered in the adjoining temples built around the time of its probable construction. Its animal form, the lion, has long been a symbol associated with the sun in ancient Near Eastern civilizations. Images depicting the Egyptian king in the form of a lion smiting his enemies appear as far back as the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt. The sphinx of Giza is an ancient iconic mythical creature usually comprised of a recumbent lion—animal with sacred solar associations—with a human head, usually that of a pharaoh, probably that of Khafre.[2]

During the New Kingdom, the Sphinx became more specifically associated with the god Hor-em-akhet (Greek Harmachis) or Horus at the Horizon, which represented the Pharaoh in his role as the Shesep ankh of Atum (living image of Atum). A temple was built to the northeast of the Sphinx by King Amenhotep II, nearly a thousand years after its construction, dedicated to the cult of Horemakhet.

Greek sphinx

While it is more than likely that the Greeks acquired the idea of the sphinx through cultural diffusion, they nonetheless incorporated it to a large degree into their written mythology and gave it its name (a potential combination of the Greek verb σφινγω — sphingo, meaning "to strangle" and the name Φιξ — Phix.

There was a single Sphinx in Greek mythology, a unique demon of destruction and bad luck, according to Hesiod a daughter of Echidna and of Orthrus or, according to others, of Typhon and Echidna. She was represented in vase-painting and bas-reliefs most often seated upright rather than recumbent, as Hera or Ares sent the Sphinx from her Ethiopian homeland (the Greeks remembered the Sphinx's foreign origin) to Thebes, where she guarded the entrance to the city, asking all those who passed her famous riddle "Which creature in the morning goes on four feet, at noon on two, and in the evening upon three?" All those who answered wrong were killed, and it was not until Oedipus came along and solved the riddle that the besieged city was liberated, making Oedipus King and setting the background for his mythical fall from grace (the answer to the riddle is man; a baby crawls when young, walks on two legs as an adult, and uses a cane in old age).[3] Bested at last, the Sphinx then threw herself from her high rock and died. An alternative version tells that she devoured herself. The exact riddle asked by the Sphinx was not specified by early tellers of the story and was not standardized as the one given above until much later in Greek history. Thus Oedipus can be recognized as a liminal or "threshold" figure, helping effect the transition between the old religious practices, represented by the Sphinx, and new, Olympian ones.

Sphinx in South and South-East Asia

In contrast to the sphinx in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Greece, where the traditions have been largely lost due to the discontinuity of the civilization,[4] the traditions of the "Asian sphinx" are still very much alive. The earliest artistic depictions of "sphinxes" from the South Asian subcontinent are to some extend influenced by Hellenistic art. But the "sphinxes" from Mathura, Kausambi, and Sanchi, dated to the third century B.C.E. till the first century C.E., also show a considerable non-Hellenist, indigenous character. It is therefore not possible to conclude the concept of the "sphinx" originated through foreign influence.[5].

In South India the "sphinx" is known as purushamriga (Sanskrit) or purushamirukam (Tamil, meaning human-beast). It is found depicted in sculptural art in temples and palaces where it serves an apotropiac purpose, just like the "sphinxes" in other parts of the ancient world.[6] According to tradition, it is said to take away the sins of the devotees when they enter a temple and to ward off evil in general. It is therefore often found in a strategic position on the gopuram or temple gateway, or near the entrance of the Sanctum Sanctorum.

The purushamriga plays a significant role in daily as well as yearly rituals of South Indian Shaiva temples. In the sodasa-upacara (or 16 honors) ritual, performed between one to six times at significant sacred moments throughout the day, it decorates one of the lamps of the diparadhana or lamp ceremony. And in several temples the purushamriga is also one of the vahana, or vehicles of the deity during the processions of the Brahmotsava or festival.

In the Kanya Kumari district, in the southernmost tip of the Indian subcontinent, during the night of Shiva Ratri, devotees run 75 kilometers while visiting and worshiping at twelve Shiva temples. This Shiva Ottam (or Run for Shiva) is performed in commemoration of the story of the race between the Sphinx and Bhima, one of the heroes of the epic Mahabharata.

In Sri Lanka, the sphinx is known as narasimha or man-lion. As a sphinx it has the body of a lion and the head of a human being, and is not to be confused with Narasimha, the fourth reincarnation of the deity Mahavishnu; this avatara or incarnation is depicted with a human body and the head of a lion. The "sphinx" narasimha is part of the Buddhist tradition and functions as a guardian of the northern direction and was also depicted on banners.

In Myanmar, the sphinx is known as manusiha and manuthiha. It is depicted on the corners of Buddhist stupas, and its legends tell how it was created by Buddhist monks to protect a new born royal baby from being devoured by ogresses.

Nora Nair and Thep Norasingh are two of the names under which the "sphinx" is known in Thailand. They are depicted as upright walking beings with the lower body of a lion or deer, and the upper body of a human. Often they are found as male-female pairs. Here too it serves a protective function. It is also enumerated among the mythological creatures that inhabit the ranges of the sacred mountain Himmapan[7].

Similar creatures

Not all human-headed animals of antiquity are sphinxes. In ancient Assyria, for example, bas-reliefs of bulls with the crowned bearded heads of kings guarded the entrances to temples. In the classical Olympian mythology of Greece, all the deities had human form, though they could assume their animal natures as well. All the creatures of Greek myth that combine human and animal form are survivals of the pre-Olympian religion: centaurs, Typhon, Medusa, Lamia. In Hindu tradition, one of the Avatars of Vishnu was the Narasimha which means 'man-lion'. The Avatar had a human body and the head of a lion.

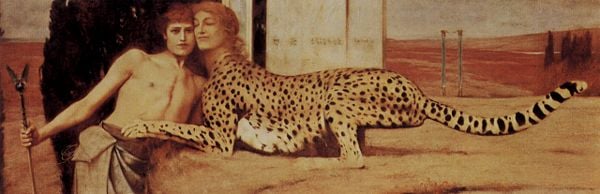

Artistic Representations

Beyond the monuments in Egypt, the sphinx has been depicted in art for centuries. Some of the most famous depictions, ranging from ancient Greece to Asia, are variations of Odeipus' encounter with the sphinx. Some depictions show a sphinx in a position of power and wisdom, looking down on Oedipus as he tries to solve the riddle, while others depict the battle of minds as an epic, mortal fight.[8] In any case, the artistic iconography of the Greek legend represents man's ability to penetrate the mysteries of the world, to use his mind in epic measures.

The revived Mannerist Sphinx of the sixteenth century is sometimes thought of as the French Sphinx. Her lovely coiffed head is erect and she has the pretty bust of a young woman. Often she wears pearls. Her body is naturalistically rendered as a recumbent lion. Such Sphinxes were revived when the grottesche or "grotesque" decorations of the unearthed "Golden House" (Domus Aurea) of Nero were brought to light in late fifteenth century Rome, and she was incorporated into the classical vocabulary of arabesque designs that was spread throughout Europe in engravings during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Her first appearances in French art are in the School of Fontainebleau in the 1520s and 1530s; her last appearances are in the Late Baroque style of the French Régence (1715–1723).

Notes

- ↑ Mallet, D. Translation. Retrieved February 22, 20007.

- ↑ Winston, Allen. 2003. "The Great Sphinx of Giza: An Introduction" Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ↑ Hamilton, Edith. 1942. Mythology. New York, NY: Little Brown. ISBN 0316341517

- ↑ Demisch, Heinz. 1977. Die Sphinx. Geschichte ihrer Darstellung von den Anfangen bis zur Gegenwart.

- ↑ The Sphinx in Early Indian Art Retrieved February 9, 2007.

- ↑ Demisch, Heinz. 1977. Die Sphinx. Geschichte ihrer Darstellung von den Anfangen bis zur Gegenwart.

- ↑ Thep Norasri Retrieved February 9, 2007.

- ↑ 2007. "Sphinx". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hamilton, Edith. 1998. (original 1942). Mythology. Back Bay Books. ISBN 0316341517

- Hancock, Graham & Robert Bauval. 1997. The Message of the Sphinx: A Quest for the Hidden Legacy of Mankind. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0517888521

- Regier, Willis Goth. 2005. Book of the Sphinx. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0750938617

- Zivie-Coche, Christiane. 2004. Sphinx: History Of A Monument . Ithica NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801489547

External links

- Al Maqrizi's account in Arabic

- An academic article arguing the case for water erosion evidence

- Egypt—The Lost Civilization Theory

- Oedipus & the Sphinx The Classics Pages

- Satellite images of Great Sphinx of Giza at WikiMapia

- Sphinx photo gallery

- The Sphinx's Nose

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.