Shark

| Sharks

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Oceanic whitetip shark, Carcharhinus longimanus

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

Carcharhiniformes |

Shark is the common name for any member of several orders of cartilaginous fish comprising the taxonomic group Selachimorpha (generally a superorder) of the subclass Elasmobranchii of the class Chondrichthyess. Sharks are characterized by a streamlined body, five to seven gill slits, replaceable teeth, and a covering of dermal denticles to protect their skin from damage and parasites and to improve fluid dynamics (Budker 1971). Unlike the closely related rays, sharks have lateral gill openings, pectoral girdle halves not joined dorsally, and the anterior edge of the pectoral fin is not attached to the side of the head (Nelson 1994).

Sharks are one of the world's misunderstood predators, as they rarely attack humans unless provoked. Humans kill approximately 26 to 73 million sharks every year, while shark attacks result in approximately five human deaths each year.[citation needed] Many shark deaths are the result of the harvesting of fins for shark fin soup, but large numbers of sharks are also caught accidentally by commercial fisheries.

Overview

The Chondrichthyes or "cartilaginous fishes" are jawed fish with paired fins, paired nostrils, scales, two-chambered hearts, and skeletons made of cartilage rather than bone. They are divided into two subclasses: Elasmobranchii (sharks, rays, and skates) and Holocephali (chimaera, sometimes called ghost sharks). The Elasmobranchii are sometimes divided into two superorders, Selachimorpha (sharks) and Batoidea (rays, skates, sawfish). Nelson (1994) notes that there is growing acceptance of the view that sharks and rays form a monophyletic group (superorder Euselachii), and sharks without rays are a paraphyletic group.

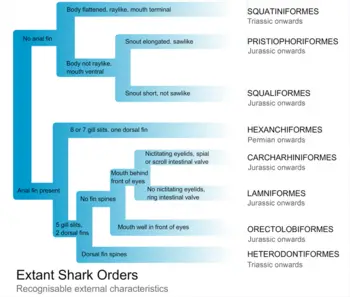

The extant (living) orders of Elasmobranchii that are typically considered sharks are Hexanchiformes, Squaliformes, Squatiniformes, and Pristiophoriformes, Heterodontiformes, Orectolobiformes, and Lamniformes, and Carchariniformes (Nelson 1994; Murch 2007). The squatiniformes (angel sharks) have a ray-like body (Nelson 1994).

Sharks include species ranging from the hand-sized pygmy shark, Euprotomicrus bispinatus, a deep sea species of only 22 centimeters (nine inches) in length, to the whale shark, Rhincodon typus, the largest fish, which grows to a length of approximately 12 meters (41 feet) and which, like the great whales, feeds only on plankton through filter feeding.

The bull shark, Carcharhinus leucas, is the best known of several species to swim in both salt and fresh water and in deltas (Allen 1999).

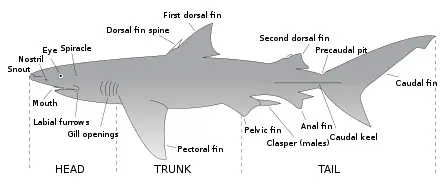

Physical Characteristics

Skeleton

The skeleton of a shark is very different from that of bony fishes such as cod. Sharks and their relatives, skates and rays, have skeletons made from rubbery cartilage, which is very light and flexible. But the cartilage in older sharks can sometimes be partly calcified, making it harder and more bone-like. The shark's jaw is variable and is thought to have evolved from the first gill arch. It is not attached to the cranium and has extra mineral deposits to give it greater strength.[1]

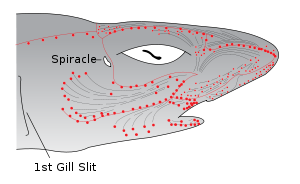

Respiration

Like other fish, sharks extract oxygen from seawater as it passes over their gills. Shark gill slits are not covered like other fish, but are in a row behind its head. Some sharks have a modified slit called a spiracle located just behind the eye, which is used in respiration.[2] While moving, water passes through the mouth of the shark and over the gills — this process is known as "ram ventilation". While at rest, most sharks pump water over their gills to ensure a constant supply of oxygenated water. A small subset of shark species that spend their life constantly swimming, a behavior common in pelagic sharks, have lost the ability to pump water through their gills. These species are obligate ram ventilators and would presumably asphyxiate if unable to stay in motion. (Obligate ram ventilation is also true of some pelagic fish species.)[3]

The respiration and circulation process begins when deoxygenated blood travels to the shark's two-chambered heart. Here the blood is pumped to the shark's gills via the ventral aorta artery where it branches off into afferent brachial arteries. Reoxygenation takes place in the gills and the reoxygenated blood flows into the efferent brachial arteries, which come together to form the dorsal aorta. The blood flows from the dorsal aorta throughout the body. The deoxygenated blood from the body then flows through the posterior cardinal veins and enters the posterior cardinal sinuses. From there blood enters the ventricle of the heart and the cycle repeats.

Buoyancy

Unlike bony fishes, sharks do not have gas-filled swim bladders, but instead rely on a large liver filled with oil that contains squalene. The liver may constitute up to 25% of their body mass[4] for buoyancy. Its effectiveness is limited, so sharks employ dynamic lift to maintain depth and sink when they stop swimming. Some sharks, if inverted, enter a natural state of tonic immobility - researchers use this condition for handling sharks safely.[5]

Osmoregulation

In contrast to bony fishes, sharks do not drink seawater; instead they retain high concentrations of waste chemicals in their body to change the diffusion gradient so that they can absorb water directly from the sea. This adaptation prevents most sharks from surviving in fresh water, and they are therefore confined to a marine environment. A few exceptions to this rule exist, such as the bull shark, which has developed a way to change its kidney function to excrete large amounts of urea.[4]

Teeth

The teeth of carnivorous sharks are not attached to the jaw, but embedded in the flesh, and in many species are constantly replaced throughout the shark's life; some sharks can lose 30,000 teeth in a lifetime. All sharks have multiple rows of teeth along the edges of their upper and lower jaws. New teeth grow continuously in a groove just inside the mouth and move forward from inside the mouth on a "conveyor belt" formed by the skin in which they are anchored. In some sharks rows of teeth are replaced every 8–10 days, while in other species they could last several months. The lower teeth are primarily used for holding prey, while the upper ones are used for cutting into it.[2] The teeth range from thin, needle-like teeth for gripping fish to large, flat teeth adapted for crushing shellfish.

Tails

The tails (caudal fins) of sharks vary considerably between species and are adapted to the lifestyle of the shark. The tail provides thrust and so speed and acceleration are dependent on tail shape. Different tail shapes have evolved in sharks adapted for different environments. The tiger shark's tail has a large upper lobe which delivers the maximum amount of power for slow cruising or sudden bursts of speed. The tiger shark has a varied diet, and because of this it must be able to twist and turn in the water easily when hunting, whereas the porbeagle, which hunts schooling fishes such as mackerel and herring has a large lower lobe to provide greater speed to help it keep pace with its fast-swimming prey. It is also believed that sharks use the upper lobe of their tails to counter the lift generated by their pectoral fins. [6]

Some tail adaptations have purposes other than providing thrust. The cookiecutter shark has a tail with broad lower and upper lobes of similar shape which are luminescent and may help to lure prey towards the shark. The thresher feeds on fish and squid, which it is believed to herd, then stun with its powerful and elongated upper lobe.

Dermal denticles

Unlike bony fish, sharks have a complex dermal corset made of flexible collagenous fibres and arranged as a helical network surrounding their body. This works as an outer skeleton, providing attachment for their swimming muscles and thus saving energy. Their dermal teeth give them hydrodynamic advantages as they reduce turbulence when swimming.[citation needed]

Body temperature

A few of the larger species, such as the shortfin mako, Isurus oxyrinchus, and the great white, are mildly homeothermic[6] - able to maintain their body temperature above the surrounding water temperature. This is possible because of the presence of the rete mirabile, a counter current exchange mechanism that reduces the loss of body heat. Muscular contraction also generates a mild amount of body heat. However, this differs significantly from true homeothermy, as found in mammals and birds, in which heat is generated, maintained, and regulated by metabolic activity.

Etymology

Until the 16th century,[7] sharks were known to mariners as "sea dogs".[8] According to the OED the name "shark" first came into use after Sir John Hawkins' sailors exhibited one in London in 1569 to refer to the large sharks of the Caribbean Sea, and later as a general term for all sharks. The name may have been derived from the Mayan word for fish, xoc, pronounced "shock" or "shawk".

Evolution

The fossil record of sharks extends back over 450 million years - before land vertebrates existed and before many plants had colonised the continents.[9] The first sharks looked very different from modern sharks.[10] The majority of the modern sharks can be traced back to around 100 million years ago.[11]

Mostly only the fossilized teeth of sharks are found, although often in large numbers. In some cases pieces of the internal skeleton or even complete fossilized sharks have been discovered. Estimates suggest that over a span of a few years a shark may grow tens of thousands of teeth, which explains the abundance of fossils. As the teeth consist of mineral apatite (calcium phosphate), they are easily fossilized.

Instead of bones, sharks have cartilagenous skeletons, with a bone-like layer broken up into thousands of isolated apatite prisms. When a shark dies, the decomposing skeleton breaks up and the apatite prisms scatter. Complete shark skeletons are only preserved when rapid burial in bottom sediments occurs.

Among the most ancient and primitive sharks is Cladoselache, from about 370 million years ago,[10] which has been found within the Paleozoic strata of Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee. At this point in the Earth's history these rocks made up the soft sediment of the bottom of a large, shallow ocean, which stretched across much of North America. Cladoselache was only about 1 m long with stiff triangular fins and slender jaws.[10] Its teeth had several pointed cusps, which would have been worn down by use. From the number of teeth found in any one place it is most likely that Cladoselache did not replace its teeth as regularly as modern sharks. Its caudal fins had a similar shape to the pelagic makos and great white sharks. The discovery of whole fish found tail first in their stomachs suggest that they were fast swimmers with great agility.

From about 300 to 150 million years ago, most fossil sharks can be assigned to one of two groups. One of these, the acanthuses, was almost exclusive to freshwater environments.[12],[13] By the time this group became extinct (about 220 million years ago) they had achieved worldwide distribution. The other group, the hybodonts, appeared about 320 million years ago and was mostly found in the oceans, but also in freshwater.

Modern sharks began to appear about 100 million years ago.[11] Fossil mackerel shark teeth occurred in the Lower Cretaceous. The oldest white shark teeth date from 60 to 65 million years ago, around the time of the extinction of the dinosaurs. In early white shark evolution there are at least two lineages: one with coarsely serrated teeth that probably gave rise to the modern great white shark, and another with finely serrated teeth and a tendency to attain gigantic proportions. This group includes the extinct megalodon, Carcharodon megalodon, which like most extinct sharks is only known from its teeth. A reproduction of its jaws was based on some of the largest teeth which up to almost 17 cm (7 in) long and suggested a fish that could grow to a length of 25 to 30.5 m (80 to 100 ft). The reconstruction was found to be inaccurate, and estimates revised downwards to around 13 to 15.9 m (43 to 52 ft).

It is believed that the immense size of predatory sharks such as the great white may have arisen from the extinction of the dinosaurs and the diversification of mammals. It is known that at the same time these sharks were evolving some early mammalian groups evolved into aquatic forms. Certainly, wherever the teeth of large sharks have been found, there has also been an abundance of marine mammal bones, including seals, porpoises and whales. These bones frequently show signs of shark attack. There are theories that suggest that large sharks evolved to better take advantage of larger prey.

Classification

Sharks belong to the superorder Selachimorpha in the subclass Elasmobranchii in the class Chondrichthyes. The Elasmobranchii also include rays and skates; the Chondrichthyes also include Chimaeras. It is currently thought that the sharks form a polyphyletic group: in particular, some sharks are more closely related to rays than they are to some other sharks.

There are more than 360 described species of sharks.

There are eight orders of sharks, listed below in roughly their evolutionary relationship from more primitive to more modern species:

- Hexanchiformes: Examples from this group include the cow sharks, frilled shark and even a shark that looks on first inspection to be a marine snake.

- Squaliformes: This group includes the bramble sharks, dogfish and roughsharks, and prickly shark.

- Pristiophoriformes: These are the sawsharks, with an elongated, toothed snout that they use for slashing the fish that they eat.

- Squatiniformes: Also known as angel sharks, they are flattened sharks with a strong resemblance to stingrays and skates.

- Heterodontiformes: They are generally referred to as the bullhead or horn sharks.

- Orectolobiformes: They are commonly referred to as the carpet sharks, including zebra sharks, nurse sharks, wobbegongs and the whale shark.

- Carcharhiniformes: These are commonly referred to as the groundsharks, and some of the species include the blue, tiger, bull, reef and oceanic whitetip sharks (collectively called the requiem sharks) along with the houndsharks, catsharks and hammerhead sharks. They are distinguished by an elongated snout and a nictitating membrane which protects the eyes during an attack.

- Lamniformes: They are commonly known as the mackerel sharks. They include the goblin shark, basking shark, megamouth shark, the thresher sharks, shortfin and longfin mako sharks, and great white shark. They are distinguished by their large jaws and ovoviviparous reproduction. The Lamniformes include the extinct megalodon, Carcharodon megalodon.

Reproduction

The sex of a shark can be easily determined. The males have modified pelvic fins which have become a pair of claspers. The name is somewhat misleading as they are not used to hold on to the female, but fulfil the role of the mammalian penis.

Mating has rarely been observed in sharks. The smaller catsharks often mate with the male curling around the female. In less flexible species the two sharks swim parallel to each other while the male inserts a clasper into the female's oviduct. Females in many of the larger species have bite marks that appear to be a result of a male grasping them to maintain position during mating. The bite marks may also come from courtship behaviour: the male may bite the female to show his interest. In some species, females have evolved thicker skin to withstand these bites.

Sharks have a different reproductive strategy from most fish. Instead of producing huge numbers of eggs and fry (99.9% of which never reach sexual maturity in fishes which use this strategy), sharks normally produce around a dozen pups (blue sharks have been recorded as producing 135 and some species produce as few as two).[14] These pups are either protected by egg cases or born live. No shark species are known to provide post-natal parental protection for their young, but females have a hormone that is released into their blood during the pupping season that apparently keeps them from feeding on their young[citation needed].

There are three ways in which shark pups are born:

- Oviparity - Some sharks lay eggs. In most of these species, the developing embryo is protected by an egg case with the consistency of leather. Sometimes these cases are corkscrewed into crevices for protection. The mermaid's purse, found washed-up on beaches, is an empty egg case. Oviparous sharks include the horn shark, catshark, Port Jackson shark, and swellshark.[15]

- Viviparity - These sharks maintain a placental link to the developing young, more analogous to mammalian gestation than that of other fishes. The young are born alive and fully functional. Hammerheads, the requiem sharks (such as the bull and tiger sharks), the basking shark and the smooth dogfish fall into this category. Dogfish have the longest known gestation period of any shark, at 18 to 24 months. Basking sharks and frilled sharks are likely to have even longer gestation periods, but accurate data is lacking.[14]

- Ovoviviparity - Most sharks utilize this method. The young are nourished by the yolk of their egg and by fluids secreted by glands in the walls of the oviduct. The eggs hatch within the oviduct, and the young continue to be nourished by the remnants of the yolk and the oviduct's fluids. As in viviparity, the young are born alive and fully functional. Some species practice oophagy, where the first embryos to hatch eat the remaining eggs in the oviduct. This practice is believed to be present in all lamniforme sharks, while the developing pups of the grey nurse shark take this a stage further and consume other developing embryos (intrauterine cannibalism). The survival strategy for the species that are ovoviviparous is that the young are able to grow to a comparatively larger size before being born. The whale shark is now considered to be in this category after long having been classified as oviparous. Whale shark eggs found are now thought to have been aborted. Most ovoviviparous sharks give birth in sheltered areas, including bays, river mouths and shallow reefs. They choose such areas because of the protection from predators (mainly other sharks) and the abundance of food.

Asexual Reproduction

In December 2001, a pup was born from a female hammerhead shark who had not been in contact with a male shark for over three years. This has led scientists to believe that sharks can produce without the mating process.

After three years of research, this assumption was confirmed on May 23 2007, after determining the shark born had no paternal DNA, ruling out any sperm-storage theory as previous thought. It is unknown as to the extent of this behaviour in the wild, and how many species of shark are capable of reproducing without a mate. This observation in sharks made mammals the only remaining major vertabrate group in which the phenomenon of asexual reproduction has not been observed.

Scientists warned that this type of behaviour in the wild is rare, and probably a last ditch effort of a species to reproduce when a mate isn't present. This leads to a lack of genetic diversity, required to build defenses againsts natural threats, and if a species of shark were to rely solely on asexual reproduction, it would probably be a road to extinction and maybe attribute to the decline of blue sharks off the Irish coast.[16] [17] [18]

Shark senses

Sense of smell

Sharks have keen olfactory senses, with some species able to detect as little as one part per million of blood in seawater, up to a quarter of a mile away. They are attracted to the chemicals found in the guts of many species, and as a result often linger near or in sewage outfalls. Some species, such as nurse sharks, have external barbels that greatly increase their ability to sense prey. The short duct between the anterior and posterior nasal openings are not fused as in bony fishes.

Sharks generally rely on their superior sense of smell to find prey, but at closer range they also use the lateral lines running along their sides to sense movement in the water, and also employ special sensory pores on their heads (Ampullae of Lorenzini) to detect electrical fields created by prey and the ambient electric fields of the ocean.

Sense of sight

Shark eyes are similar to the eyes of other vertebrates, including similar lenses, corneas and retinas, though their eyesight is well adapted to the marine environment with the help of a tissue called tapetum lucidum. This tissue is behind the retina and reflects light back to the retina, thereby increasing visibility in the dark waters. The effectiveness of the tissue varies, with some sharks having stronger nocturnal adaptations. Sharks have eyelids, but they do not blink because the surrounding water cleans their eyes. To protect their eyes some have nictitating membranes. This membrane covers the eyes during predation, and when the shark is being attacked. However, some species, including the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), do not have this membrane, but instead roll their eyes backwards to protect them when striking prey. The importance of sight in shark hunting behavior is debated. Some believe that electro and chemoreception are more significant, while others point to the nictating membrane as evidence that sight is important. (Presumably, the shark would not protect its eyes were they unimportant.) The degree to which sight is used probably varies with species and water conditions.

Sense of hearing

Sharks also have a sharp sense of hearing and can hear prey many miles away. A small opening on each side of their heads (not to be confused with the spiracle) leads directly into the inner ear through a thin channel. The lateral line shows a similar arrangement, as it is open to the environment via a series of openings called lateral line pores. This is a reminder of the common origin of these two vibration- and sound-detecting organs that are grouped together as the acoustico-lateralis system. In bony fishes and tetrapods the external opening into the inner ear has been lost.

Electroreception

The Ampullae of Lorenzini are the electroreceptor organs of the shark, and they vary in number from a couple of hundred to thousands in an individual. The shark has the greatest electricity sensitivity known in all animals. This sense is used to find prey hidden in sand by detecting the electric fields inadvertently produced by all fish. It is this sense that sometimes confuses a shark into attacking a boat: when the metal interacts with salt water, the electrochemical potentials generated by the rusting metal are similar to the weak fields of prey, or in some cases, much stronger than the prey's electrical fields: strong enough to attract sharks from miles away. The oceanic currents moving in the magnetic field of the Earth also generate electric fields that can be used by the sharks for orientation and navigation.

Lateral line

This system is found in most fish, including sharks. It is used to detect motion or vibrations in the water. The shark uses this to detect the movements of other organisms, especially wounded fish. The shark can sense frequencies in the range of 25 to 50 Hz.[19]

Behaviour

Studies on the behaviour of sharks have only recently been carried out leading to little information on the subject, although this is changing. The classic view of the shark is that of a solitary hunter, ranging the oceans in search of food; however, this is only true for a few species, with most living far more sedentary, benthic lives. Even solitary sharks meet for breeding or on rich hunting grounds, which may lead them to cover thousands of miles in a year.[20] Migration patterns in sharks may be even more complex than in birds, with many sharks covering entire ocean basins.

Some sharks can be highly social, remaining in large schools, sometimes up to over 100 individuals for scalloped hammerheads congregating around seamounts and islands e.g. in the Gulf of California.[4] Cross-species social hierarchies exist with oceanic whitetip sharks dominating silky sharks of comparable size when feeding.

When approached too closely some sharks will perform a threat display to warn off the prospective predators. This usually consists of exaggerated swimming movements, and can vary in intensity according to the level of threat.[21]

Shark intelligence

Despite the common myth that sharks are instinct-driven "eating machines", recent studies have indicated that many species possess powerful problem-solving skills, social complexity and curiosity.The brain-mass-to-body-mass ratios of sharks are similar to those of mammals and other higher vertebrate species.[22]

In 1987, near Smitswinkle Bay, South Africa, a group of up to seven great white sharks worked together to relocate the partially beached body of a dead whale to deeper waters to feed.[23]

Sharks have even been known to engage in playful activities (a trait also observed in cetaceans and primates). Porbeagle sharks have been seen repeatedly rolling in kelp and have even been observed chasing an individual trailing a piece behind them.[24]

Shark sleep

Some say a shark never sleeps. It is unclear how sharks sleep. Some sharks can lie on the bottom while actively pumping water over their gills, but their eyes remain open and actively follow divers. When a shark is resting, they do not use their nares, but rather their spiracles. If a shark tried to use their nares while resting on the ocean floor, they would be sucking up sand rather than water. Many scientists believe this is one of the reasons sharks have spiracles. The spiny dogfish's spinal cord, rather than its brain, coordinates swimming, so it is possible for a spiny dogfish to continue to swim while sleeping. It is also possible that a shark can sleep with only parts of its brain in a manner similar to dolphins.[25]

Habitat

A December 10, 2006 report by the Census of Marine Life group reveals that 70% of the world's oceans are shark-free. They have discovered that although many sharks live up to depths as low as 1,500 m (5,000 ft), they fail to colonize deeper, putting them more easily within reach of fisheries and thus endangered status.[26]

Shark attacks

Contrary to popular belief, only a few sharks are dangerous to humans. Out of more than 360 species, only four have been involved in a significant number of fatal, unprovoked attacks on humans: the great white, tiger, oceanic whitetip and bull sharks.[27] These sharks, being large, powerful predators, may sometimes attack and kill people, but all of these sharks have been filmed in open water, without the use of a protective cage.[28]

The perception of sharks as dangerous animals has been popularised by publicity given to a few isolated unprovoked attacks, such as the Jersey Shore Shark Attacks of 1916, and through popular fictional works about shark attacks, such as the Jaws film series. The author of Jaws, Peter Benchley, had in his later years attempted to dispel the image of sharks as man-eating monsters. In 2005, according to the International Shark Attack File, there were a total of 58 unprovoked attacks recorded worldwide, of which four were fatal.[29]

In 2005 the International Shark Attack File (ISAF) undertook an investigation into 105 shark attacks. Out of those 105, 58 of the attacks were unprovoked. [30]

Sharks in captivity

Until recently only a few benthic species of shark, such as hornsharks, leopard sharks and catsharks could survive in aquarium conditions for up to a year or more. This gave rise to the belief that sharks, as well as being difficult to capture and transport, were difficult to care for. A better knowledge of sharks has led to more species (including the large pelagic sharks) being able to be kept for far longer. At the same time, transportation techniques have improved and now provide a way for the long distance movement of sharks.[31]

Despite being considered critical for the health of the shark, very few studies on feeding have been carried out. Since food is the reward for appropriate behaviour, trainers must rely on control of feeding motivation.

Conservation

The majority of shark fisheries around the globe have little monitoring or management. With the rise in demand of shark products there is a greater pressure on fisheries.[32] Stocks decline and collapse because sharks are long-lived apex predators with comparatively small populations, which makes it difficult for them breed rapidly enough to maintain population levels. Major declines in shark stocks have been recorded in recent years - some species have been depleted by over 90% over the past 20-30 years with a population decline of 70% not being unusual.[33] Many governments and the UN have acknowledged the need for shark fisheries management, but due to the low economic value of shark fisheries, the small volumes of products produced and the poor public image of sharks, little progress has been made.

Many other threats to sharks include habitat alteration, damage and loss from coastal developments, pollution and the impact of fisheries on the seabed and prey species.

A Canadian-made documentary, Sharkwater is raising awareness of the depletion of the world's shark population.

Shark fishery

Every year, an estimate states that 26 to 73 million (median value is at 38 million) sharks are killed by people in commercial and recreational fishing.[34] In the past, sharks were killed simply for the sport of landing a good fighting fish (such as the shortfin mako sharks). Shark skin is covered with dermal denticles, which are similar to tiny teeth, and was used for purposes similar to sandpaper. Other sharks are hunted for food (Atlantic thresher, shortfin mako and others), and some species for other products.[35]

Sharks are a common seafood in many places around the world, including Japan and Australia. In the Australian State of Victoria shark is the most commonly used fish in fish and chips, in which fillets are battered and deep-fried or crumbed and grilled and served alongside chips. When served in fish and chip shops, it is called flake.

Sharks are often killed for shark fin soup: the finning process involves capture of a live shark, the removal of the fin with a hot metal blade, and the release of the live animal back into the water. Sharks are also killed for their meat. The meat of dogfishes, smoothhounds, catsharks, skates and rays are in high demand by European consumers.[citation needed] The situation in Canada and the United States is similar: the blue shark is sought as a sport fish while the porbeagle, mako and spiny dogfish are part of the commercial fishery.[citation needed] There have been cases where hundreds of de-finned sharks were swept up on local beaches without any way to convey themselves back into the sea.[citation needed] Conservationists have campaigned for changes in the law to make finning illegal in the U.S.

Shark cartilage has been advocated as effective against cancer and for treatment of osteoarthritis(This is because many people believe that sharks cannot get cancer and that taking it will prevent people from getting these diseases, which is untrue.) . However, a trial by Mayo Clinic found no effect in advanced cancer patients.

Sharks generally reach sexual maturity slowly and produce very few offspring in comparison to other fishes that are harvested. This has caused concern among biologists regarding the increase in effort applied to catching sharks over time, and many species are considered to be threatened.

Some organizations, such as the Shark Trust, campaign to limit shark fishing.

Sharks in mythology

Sharks figure prominently in the Hawaiian mythology. There are stories of shark men who have shark jaws on their back. They could change form between shark and human at any time they desired. A common theme in the stories was that the shark men would warn beach-goers that sharks were in the waters. The beach-goers would laugh and ignore the warnings and go swimming, subsequently being eaten by the same shark man who warned them not to enter the water.

Hawaiian mythology also contained many shark gods. They believed that sharks were guardians of the sea, and called them Aumakua:[36]

- Kamohoali'i - The best known and revered of the shark gods, he was the older and favoured brother of Pele,[37] and helped and journeyed with her to Hawaii. He was able to take on all human and fish forms. A summit cliff on the crater of Kilauea is considered to be one of his most sacred spots. At one point he had a he'iau (temple or shrine) dedicated to him on every piece of land that jutted into the ocean on the island of Moloka'i.

- Ka'ahupahau - This goddess was born human, with her defining characteristic being her red hair. She was later transformed into shark form and was believed to protect the people who lived on O'ahu from sharks. She was also believed to live near Pearl Harbor.

- Kaholia Kane - This was the shark god of the ali'i Kalaniopu'u and he was believed to live in a cave at Puhi, Kaua'i.

- Kane'ae - The shark goddess who transformed into a human in order to experience the joy of dancing.

- Kane'apua - Most commonly, he was the brother of Pele and Kamohoali'i. He was a trickster god who performed many heroic feats, including the calming of two legendary colliding hills that destroyed canoes trying to pass between.

- Kawelomahamahai'a - Another human, he was transformed into a shark.

- Keali'ikau 'o Ka'u - He was the cousin of Pele and son of Kua. He was called the protector of the Ka'u people. He had an affair with a human girl, who gave birth to a helpful green shark.

- Kua - This was the main shark god of the people of Ka'u, and believed to be their ancestor.

- Kuhaimoana - He was the brother of Pele and lived in the Ka'ula islet. He was said to be 30 fathoms (55 m) long and was the husband of Ka'ahupahau.

- Kauhuhu - He was a fierce king shark that lived in a cave in Kipahulu on the island of Maui. He sometimes moved to another cave on the windward side of island of Moloka'i.

- Kane-i-kokala - A kind shark god that saved shipwrecked people by taking them to shore. The people who worshipped him feared to eat, touch or cross the smoke of the kokala, his sacred fish.

In other Pacific Ocean cultures, Dakuwanga was a shark god who was the eater of lost souls.

Beliefs about sharks

In ancient Greece, it was forbidden to eat shark flesh at women's festivals.

A popular myth is that sharks are immune to disease and cancer; however, this is untrue. There are both diseases and parasites that affect sharks. The evidence that sharks are at least resistant to cancer and disease is mostly anecdotal and there have been few, if any, scientific or statistical studies that have shown sharks to have heightened immunity to disease.[38]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Budker|first=Paul|title=The Life of Sharks|publisher=Weidenfeld and Nicolson| location=London| date=1971| id= SBN 297003070

Andy Murch 2007 http://www.elasmodiver.com/elasmobranch_taxonomy.htm Shark taxonomy Elasmodiver.com

- ↑ Hamlett, W. C. (1999). Sharks, Skates and Rays: The Biology of Elasmobranch Fishes. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6048-2.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Gilbertson, Lance (1999). Zoology Laboratory Manual. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.. ISBN 0-07-237716-X.

- ↑ Deep Breathing, William J. Bennetta

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Compagno, Leonard and Dando, Marc & Fowler, Sarah (2005). Sharks of the World. Collins Field Guides. ISBN 0-00-713610-2.

- ↑ Pratt, H. L. Jr and Gruber, S. H.; & Taniuchi, T. (1990). Elasmobranchs as living resources: Advances in the biology, ecology, systematics, and the status of the fisheries. NOAA Tech Rept..

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Nelson, Joseph S. (1994). Fishes of the World. New York: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-54713-1.

- ↑ Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2006-08-08.

- ↑ Marx, Robert F. (1990). The History of Underwater Exploration. Courier Dover Publications, 3. ISBN 0-486-26487-4.

- ↑ Martin, R. Aidan.. Geologic Time. ReefQuest. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Martin, R. Aidan.. Ancient Sharks. ReefQuest. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Martin, R. Aidan.. The Origin of Modern Sharks. ReefQuest. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ↑ http://hoopermuseum.earthsci.carleton.ca/sharks/P2-3.htm "Xenacanth". Retrieved on 11/26/06.

- ↑ http://www.elasmo-research.org/education/evolution/earliest.htm "Biology of Sharks and Rays: 'The Earliest Sharks'". Retrieved on 11/26/06.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Leonard J. V. Compagno (1984). Sharks of the World: An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 92-5-104543-7.

- ↑ Marine Biology notes. School of Life Sciences, Napier University. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ↑ Female sharks reproduce without male DNA, scientists say. The New York Times, New York City. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ↑ No need for dad: Female shark reproduces without sex. Yahoo News. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ↑ Demian D. Chapman1, Mahmood S. Shivji, Ed Louis, Julie Sommer, Hugh Fletcher and Paulo A. Prodöhl. Virgin birth in a hammerhead shark. Biology Letters. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ↑ Popper, A.N. and C. Platt (1993). Inner ear and lateral line. The Physiology of Fishes (1st ed.).

- ↑ Scientists track shark's 12,000-mile round-trip. Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ↑ Jaws: The natural history of sharks. Natural History Museum. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ↑ Smart sharks. BBC - Science and nature. Retrieved 2006-08-07.

- ↑ Is the White Shark Intelligent. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved 2006-08-07.

- ↑ Biology of the Porbeagle. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved 2006-08-07.

- ↑ How Do Sharks Swim When Asleep?. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved 2006-08-07.

- ↑ Extreme Life, Marine Style, Highlights 2006 Ocean Census. coml.org (2006-12-10). Retrieved 2006-12-10.

- ↑ Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark. ISAF. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ↑ Great white shark spotted off Hale'iwa. Hawaiian newspaper article. Retrieved 2006-09-12. with pictures of cageless diver with great white shark.

- ↑ 2005 Worldwide Shark Attack Summary. ISAF. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ↑ http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/sharks/statistics/2005attacksummary.htm/

- ↑ Whale Sharks in Captivity. Retrieved 2006-09-13.

- ↑ Pratt, H. L. Jr. and Gruber, S. H. & Taniuchi, T. (1990). Elasmobranchs as living resources: Advances in the biology, ecology, systematics, and the status of the fisheries. NOAA Tech Rept. (90).

- ↑ Walker, T.I. (1998). Shark Fisheries Management and Biology.

- ↑ Triple Threat: World Fin Trade May Harvest up to 73 Million Sharks per Year. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ↑ FAO Shark Fisheries. Retrieved 2006-09-10.

- ↑ Hawaiian Mythology. Retrieved 2006-09-13.

- ↑ Pele, Goddess of Fire. Retrieved 2006-09-13.

- ↑ Do Sharks Hold Secret to Human Cancer Fight?. National Geographic. Retrieved 2006-09-08.

- General references

- Castro, Jose (1983). The Sharks of North American Waters. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 0-89096-143-3.

- Stevens, John D. (1987). Sharks. New York: NY Facts on File Publications. ISBN 0-8160-1800-6.

- Pough, F. H. and Janis, C. M. & Heiser, J. B. (2005). Vertebrate Life. 7th Ed.. New Jersey: Pearson Education Ltd.. ISBN 0-13-127836-3.

- Clover, Charles. 2004. The End of the Line: How overfishing is changing the world and what we eat. Ebury Press, London. ISBN 0-09-189780-7

External links

- Shark Research Institute

- Shark Conservation

- Greenland Shark and Elasmobranch Education and Research Group

- The International Shark Attack File

- Shark Trust Organization

- ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research

- ECOCEAN Whale Shark Photo-identification Library

- Photographs of sharks

- Sharks Photo gallery

- Sharkology

- Updated list of all known shark species

- Bite-Back.com

- Global Shark Attack File

- The Ocean Conservancy: Sharks

- The Shark Alliance

- Shark Research Committee

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.