Difference between revisions of "Santa Claus" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Origins) |

m |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

[[Image:Sinterklaas 2007.jpg|thumb|[[Sinterklaas]] in 2007]] | [[Image:Sinterklaas 2007.jpg|thumb|[[Sinterklaas]] in 2007]] | ||

| − | In the [[Netherlands]] and [[Belgium]], Saint Nicolas (often called "De Goede Sint" — "The Friendly Saint") is aided by helpers commonly known as [[Zwarte Piet]] ("Black Peter"). | + | In the [[Netherlands]] and [[Belgium]], Saint Nicolas (often called "De Goede Sint" — "The Friendly Saint") is aided by helpers commonly known as [[Zwarte Piet]] ("Black Peter"). |

| + | ===Santa's helpers== | ||

There are various explanations of the origins of Santas helpers, nowadays depicted as friendly elves. One theory is that the helpers symbolize the two ravens [[Hugin]] and [[Munin]] who informed Odin on what was going on. In later stories the helper depicts the defeated [[devil]]. The devil is defeated by either Odin or his helper [[Nörwi]], the black father of the night. Nörwi is usually depicted with the same staff of birch (Dutch: "roe") as Zwarte Piet. A Christianized version of the story is that Saint Nicolas liberated an [[Ethiopia]]n slave boy called "Piter" from a [[Myra]] market, and the boy was so grateful that he decided to stay with Nicolas as his servant. | There are various explanations of the origins of Santas helpers, nowadays depicted as friendly elves. One theory is that the helpers symbolize the two ravens [[Hugin]] and [[Munin]] who informed Odin on what was going on. In later stories the helper depicts the defeated [[devil]]. The devil is defeated by either Odin or his helper [[Nörwi]], the black father of the night. Nörwi is usually depicted with the same staff of birch (Dutch: "roe") as Zwarte Piet. A Christianized version of the story is that Saint Nicolas liberated an [[Ethiopia]]n slave boy called "Piter" from a [[Myra]] market, and the boy was so grateful that he decided to stay with Nicolas as his servant. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The word Krampus originates from the Old High German word for claw (Krampen). In the Alpine regions the Krampus is represented by an incubus in company of Saint Nicholas. Traditionally, young men dress up as the Krampus in the first two weeks of December, particularly in the evening of December 5, and roam the streets frightening children (and adults) with rusty chains and bells. In some rural areas the tradition also includes slight birching by the Krampus, especially of young females. | ||

===Modern origins=== | ===Modern origins=== | ||

Revision as of 15:02, 9 December 2008

Santa Claus, also known as Saint Nicholas, Father Christmas, Kris Kringle, or simply "Santa", is the figure who, in most of Western cultures, is described as bringing gifts on Christmas Eve, December 24 or on his Feast Day, December 6 (Saint Nicholas Day). The legend may have part of its basis in hagiographical tales concerning the historical figure of Saint Nicholas.

The modern depiction of Santa Claus as a fat, jolly man wearing a red coat and trousers with white cuffs and collar, and black leather belt and boots, became popular in the United States in the nineteenth century due to the significant influence of caricaturist and political cartoonist Thomas Nast. This image has been maintained and reinforced through song, radio, television, and films. In the United Kingdom and Europe, his depiction is often identical to the American Santa, but he is commonly called Father Christmas.

One legend associated with Santa says that he lives in the far north, in a land of perpetual snow. The American version of Santa Claus lives at the North Pole, while Father Christmas is said to reside in Lapland. Other details include: that he is married and lives with Mrs. Claus; that he makes a list of children throughout the world, categorizing them according to their behavior; that he delivers presents, including toys, candy, and other presents to all of the good boys and girls in the world, and sometimes coal or sticks to the naughty children, in one night; and that he accomplishes this feat with the aid of magical elves who make the toys, and eight or nine flying reindeer who pull his sleigh.

There has long been opposition to teaching children to believe in Santa Claus. Some Christians say the Santa tradition detracts from the religious origins and purpose of Christmas. Other critics feel that Santa Claus is an elaborate lie, and that it is unethical for parents to teach their children to believe in his existence.

Origins

Early Christian origins

Saint Nicholas of Myra is the primary inspiration for the Christian figure of Santa Claus. He was a fourth-century Greek Christian bishop of Myra in Lycia, a province of the Byzantine Anatolia, now in Turkey. Nicholas was famous for his generous gifts to the poor, in particular presenting the three impoverished daughters of a pious Christian with dowries to prevent them from becoming prostitutes. In Europe (more precisely the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, and Germany) he is still portrayed as a bearded bishop in canonical robes. Saint Nicholas became a patron saint of many diverse groups, from archers and children to pawnbrokers.

In many regions of Austria and former Austro-Hungarian Italy (Friuli, city of Trieste) children are given sweets and gifts on Saint Nicholas's Day (San Niccolò in Italian), in accordance with the Catholic calendar, December 6.

Influence of European folklore

Numerous parallels have been drawn between Santa Claus and the figure of Odin, a major god among the Germanic peoples prior to their Christianization. Two thirteenth books from Iceland, the Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson and the Poetic Edda compiled from earlier sources, describe Odin as riding an eight-legged horse named Sleipnir that could leap great distances, giving rise to comparisons to Santa Claus's reindeer.

Children would place their boots, filled with carrots, straw, or sugar, near the chimney for Odin's flying horse, Sleipnir, to eat. Odin would then reward those children for their kindness by replacing Sleipnir's food with gifts or candy. This practice survived in Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands after the adoption of Christianity and became associated with Saint Nicholas as a result of the process of Christianization. The modern practice of the hanging of stockings at the chimney in some homes may have derived from this tradition.

Numerous other influences from the pre-Christian Germanic winter celebrations have continued into modern Christmas celebrations such as the Christmas ham, Yule logs, and the Christmas tree.

In the Netherlands and Belgium, Saint Nicolas (often called "De Goede Sint" — "The Friendly Saint") is aided by helpers commonly known as Zwarte Piet ("Black Peter").

=Santa's helpers

There are various explanations of the origins of Santas helpers, nowadays depicted as friendly elves. One theory is that the helpers symbolize the two ravens Hugin and Munin who informed Odin on what was going on. In later stories the helper depicts the defeated devil. The devil is defeated by either Odin or his helper Nörwi, the black father of the night. Nörwi is usually depicted with the same staff of birch (Dutch: "roe") as Zwarte Piet. A Christianized version of the story is that Saint Nicolas liberated an Ethiopian slave boy called "Piter" from a Myra market, and the boy was so grateful that he decided to stay with Nicolas as his servant.

The word Krampus originates from the Old High German word for claw (Krampen). In the Alpine regions the Krampus is represented by an incubus in company of Saint Nicholas. Traditionally, young men dress up as the Krampus in the first two weeks of December, particularly in the evening of December 5, and roam the streets frightening children (and adults) with rusty chains and bells. In some rural areas the tradition also includes slight birching by the Krampus, especially of young females.

Modern origins

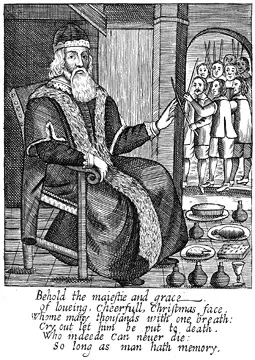

Pre-modern representations of the gift-giver from church history and folklore merged with the British character Father Christmas to create the character known to Britons and Americans as Santa Claus. Father Christmas dates back at least as far as the seventeenth century in Britain, and pictures of him survive from that era, portraying him as a well-nourished bearded man dressed in a long, green, fur-lined robe. He typified the spirit of good cheer at Christmas, and was reflected in the "Ghost of Christmas Present" in Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol.

In other countries, the figure of Saint Nicholas was also blended with local folklore. As an example of the still surviving pagan imagery, in Nordic countries the original bringer of gifts at Christmas time was the Yule Goat, a somewhat startling figure with horns.

In the 1840s however, an elf in Nordic folklore called "Tomte" or "Nisse" started to deliver the Christmas presents in Denmark. The Tomte was portrayed as a short, bearded man dressed in gray clothes and a red hat. This new version of the age-old folkloric creature was obviously inspired by the Santa Claus traditions that were now spreading to Scandinavia. By the end of the nineteenth century, this tradition had also spread to Norway and Sweden, replacing the Yule Goat. The same thing happened in Finland, but there the more human figure retained the Yule Goat name. But even though the tradition of the Yule Goat as a bringer of presents is now all but extinct, a straw goat is still a common Christmas decoration in all of Scandinavia.

American origins

In the British colonies of North America and later the United States, British and Dutch versions of the gift-giver merged further. For example, in Washington Irving's History of New York, (1809), Sinterklaas was Americanized into "Santa Claus" but lost his bishop's apparel, and was at first pictured as a thick-bellied Dutch sailor with a pipe in a green winter coat. Irving's book was a lampoon of the Dutch culture of New York, and much of this portrait is his joking invention.

Modern ideas of Santa Claus seemingly became canon after the publication of the poem "A Visit From St. Nicholas" (better known today as "The Night Before Christmas") in the Troy, New York, Sentinel on December 23 1823 anonymously; the poem was later attributed to Clement Clarke Moore. In this poem Santa is established as a heavyset man with eight reindeer (who are named for the first time). One of the first artists to define Santa Claus's modern image was Thomas Nast, an American cartoonist of the nineteenth century. In 1863, a picture of Santa illustrated by Nast appeared in Harper's Weekly.

In the late-nineteenth century, a group of Sami people moved from Finnmark in Norway to Alaska, together with 500 reindeer to teach the Inuit to herd reindeer. The Lomen Company then used several of the Sami together with reindeer in a commercial campaign. Reindeer pulled sleds with a Santa, and one Sami leading each reindeer. The American commercial Santa Claus, coming from the North Pole with reindeer was born.

L. Frank Baum's The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus, a 1902 children's book, further popularized Santa Claus. Much of Santa Claus's mythos was not set in stone at the time, leaving Baum to give his "Neclaus" (Necile's Little One) a wide variety of immortal support, a home in the Laughing Valley of Hohaho, and ten reindeer which could not fly, but leapt in enormous, flight-like bounds. Claus's immortality was earned, much like his title ("Santa"), decided by a vote of those naturally immortal. This work also established Claus's motives: a happy childhood among immortals. When Ak, Master Woodsman of the World, exposes him to the misery and poverty of children in the outside world, Santa strives to find a way to bring joy into the lives of all children, and eventually invents toys as a principal means.

Images of Santa Claus were further popularized through Haddon Sundblom's depiction of him for The Coca-Cola Company's Christmas advertising in the 1930s. The popularity of the image spawned urban legends that Santa Claus was in fact invented by Coca-Cola or that Santa wears red and white because they are the Coca-Cola colors. In reality, Coca-Cola was not the first soft drink company to utilize the modern image of Santa Claus in its advertising – White Rock Beverages used Santa to sell mineral water in 1915 and then in advertizements for its ginger ale in 1923.

The image of Santa Claus as a benevolent character became reinforced with its association with charity and philanthropy, particularly organizations such as the Salvation Army. Volunteers dressed as Santa Claus typically became part of fundraising drives to aid needy families at Christmas time.

In 1889, the poet Katherine Lee Bates created a wife for Santa, Mrs. Claus, in the poem "Goody Santa Claus on a Sleigh Ride." The 1956 popular song by George Melachrino, "Mrs. Santa Claus," helped standardize and establish the character and role in the popular imagination.

In some images of the early twentieth century, Santa was depicted as personally making his toys by hand in a small workshop like a craftsman. Eventually, the idea emerged that he had numerous elves responsible for making the toys, but the toys were still handmade by each individual elf working in the traditional manner.

The 1947 film, Miracle on 34th Street tells the story of what takes place in New York City following Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade, as people are left wondering whether or not a department store Santa might be the real thing. There have been four remakes of the movie, as well as a Broadway musical. Among others, the film won an Academy Award for Edmund Gwenn for Best Supporting Actor for his portayal of Kris Kringle.

The concept of Santa Claus continues to inspire writers and artists, as in author Seabury Quinn's 1948 novel Roads, which draws from historical legends to tell the story of Santa and the origins of Christmas. Other modern additions to the "mythology" of Santa include Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, the ninth and lead reindeer immortalized in a Gene Autry song, written by a Montgomery Ward copywriter.

Santa Claus in popular culture

By the end of the twentieth century, the reality of mass-mechanized production became more fully accepted by the Western public. That shift was reflected in the modern depiction of Santa's residence—now often humorously portrayed as a fully mechanized production and distribution facility, equipped with the latest manufacturing technology, and overseen by the elves with Santa and Mrs. Claus as executives and/or managers. Many television commercials, comic strips, and other media depict this as a sort of humorous business, with Santa's elves acting as a sometimes mischievously disgruntled workforce, cracking jokes and pulling pranks on their boss.

NORAD, the joint Canadian-American military organization responsible for air defense, regularly reports tracking Santa Claus every year.

In Kyrgyzstan, a mountain peak was named after Santa Claus, after a Swedish company had suggested the location be a more efficient starting place for present-delivering journeys all over the world, than Lapland. In the Kyrgyz capital, Bishkek, a Santa Claus Festival was held on December 30, 2007, with government officials attending. Later, 2008 was officially declared the Year of Santa Claus in the country. The events are seen as moves to boost tourism in Kyrgyzstan, which is predominately Muslim.

Criticism

Christian opposition

Condemnation of Santa Claus originated among some Protestant groups of the sixteenth century. It was also prevalent among the Puritans of seventeenth-century England and America, who banned the holiday as either pagan or Roman Catholic. Following the English Civil War, under Oliver Cromwell's government Christmas was banned. With the Restoration of the monarchy and the Puritans out of power in England, the ban on Christmas was satirized in works such as Josiah King's The Examination and Tryal of Old Father Christmas; Together with his Clearing by the Jury (1686) [Nissenbaum, chap. 1].

Rev. Paul Nedergaard, a clergyman in Copenhagen, Denmark, attracted controversy in 1958 when he declared Santa to be a "pagan goblin" after Santa's image was used on fund-raising materials for a Danish welfare organization Clar, 337. One prominent religious group that refuses to recognize Santa Claus, or Christmas itself, for similar reasons is the Jehovah's Witnesses.

Deception controversy

The belief in Santa Claus by children is widespread. In an AP-AOL News poll, 86 percent of American adults believed in Santa as children, with the age of eight being the average for stopping to believe he is real, although 15 percent still believed after the age of 10.[1]

Parental and societal encouragement of this belief is not without controversy. The editors of Netscape framed one complaint about the Santa Claus myth: "Parents who encourage a belief in Santa are foisting a grand deception on their children, who inevitably will be disappointed and disillusioned."[2] University of Texas at Austin psychology professor Jacqueline Woolley contradicts the notion that a belief in Santa is evidence of the gullibility of children, but evidence that they believe what their parents tell them and society reinforces. Woolley posits that it is perhaps "kinship with the adult world" that causes children not to be angry that they were lied to for so long. The criticism about this deception is not that it is a simple lie, but a complicated series of very large lies.[3] The objections to the lie are that it is unethical for parents to lie to children without good cause, and that it discourages healthy skepticism in children.[3] With no greater good at the heart of the lie, it is charged that it is more about the parents than it is about the children. Writer Austin Cline posed the question: "Is it not possible that kids would find at least as much pleasure in knowing that parents are responsible for Christmas, not a supernatural stranger?"[3]

Dr. John Condry of Cornell University interviewed more than 500 children for a study of the issue and found that not a single child was angry at his or her parents for telling them Santa Claus was real. According to Dr. Condry, "The most common response to finding out the truth was that they felt older and more mature. They now knew something that the younger kids didn't."[4]

Home of Santa Claus

In American tradition, Santa lives on the North Pole. However, each Nordic country claims Santa's residence to be within their territory. In Denmark, he is told to live on Greenland. In Sweden, the town of Mora has a themepark named Tomteland. The national postal terminal in Tomteboda in Stockholm receives childrens' letters for Santa. The Finnish town Rovaniemi has long been known in Finland as Santa's home, and has today a themepark called Santa Claus Village.

Notes

- ↑ AP Poll: Santa Claus Endures in America, Calvin Woodward, Washington Post, December 23, 2006.

- ↑ Is It OK for Kids to Believe in Santa?, editors of Netscape

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Santa Claus: Should Parents Perpetuate the Santa Claus Myth?, Austin Cline, About.com

- ↑ KUTNER, LAWRENCE; Parent & Child; New York Times; 1991-11-21; Retrieved on 2007-12-22

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baum, L. Frank. The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus. New York: Penguin, 1986. ISBN 0-451-52064-5

- Clark, Cindy Dell. Flights of Fancy, Leaps of Faith: Children's Myths in Contemporary America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995. ISBN 0-226-10778-7

- Horowitz, Joseph. Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall. New York: W. W. Norton, 2005. ISBN 0-393-05717-8

- Nissenbaum, Stephen. The Battle for Christmas. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996. ISBN 0-679-74038-4

- Sedaris, David. The Santaland Diaries and Seasons Greetings: Two Plays. New York: Dramatists Play Service, 1998. ISBN 0-8222-1631-0

- Shenkman, Richard. Legends, Lies, and Cherished Myths of American History. New York: HarperCollins, 1988. ISBN 0-06-097261-0

- Siefker, Phyllis. Santa Claus, Last of the Wild Men: The Origins and Evolution of Saint Nicholas, Spanning 50,000 Years. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1996. ISBN 0-7864-0246-6

External links

- Norman Rockwell's Santa and Expense Book

- SantaLand.com, one of the Internet's oldest Santa-related website, founded in 1991 by former Library of Congress archivist Jeff Guide

- NORAD Tracks Santa

- North Pole Flooded With Letters - MSNBC

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.