Difference between revisions of "Pyramids of Giza" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (41 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Anthropology]] | [[Category:Anthropology]] | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Archaeological sites]] | |

{{Infobox World Heritage Site | {{Infobox World Heritage Site | ||

| WHS = Memphis and its Necropolis - the Pyramid Fields from Giza to Dahshur | | WHS = Memphis and its Necropolis - the Pyramid Fields from Giza to Dahshur | ||

| − | | Image = [[Image:Pyramids of Egypt1.jpg| | + | | Image = [[Image:Pyramids of Egypt1.jpg|250px|The Giza Pyramids, part of the Giza Necropolis]] |

| State Party = {{EGY}} | | State Party = {{EGY}} | ||

| Type = Cultural | | Type = Cultural | ||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | [[ | + | The '''Giza Necropolis''' stands on the Giza Plateau, on the outskirts of [[Cairo]], [[Egypt]]. This complex of ancient monuments is located some eight kilometers (5 miles) inland into the desert from the old town of [[Giza]] on the [[Nile]], some 25 kilometres (12.5 miles) southwest of Cairo city center. |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | The | + | The complex contains three large pyramids, the most famous of which, the [[Great Pyramid of Giza|Great Pyramid]] was built for the pharaoh Khufu and is possibly the largest building ever erected on the planet, and the last member of the ancient [[Seven Wonders of the World]]. The other two pyramids, each impressive in their own right, were built for the kings Khafre and Menkaure. The site also contains the [[Sphinx]], a monstrous statue of a part-lion, part-human, mysterious both in appearance and in its origin and purpose, and the Khufu Ship, the relic of a boat built to transport Khufu to the [[afterlife]]. |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | This [[necropolis]], an amazing collection of buildings that were constructed to house the dead, reveals much about the [[civilization]] of [[ancient Egypt]]. Scientists continue to research and theorize about how and why they were constructed, and their true meaning to those who initiated them. For the general public, though, the sense of wonder and respect that they command may be sufficient. | ||

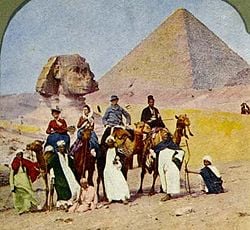

| + | [[Image:SphynxTourists.JPG|thumb|250px|Nineteenth-century tourists in front of the Sphinx - view from South-East, Great Pyramid in background]] | ||

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| − | This [[Ancient Egypt]]ian [[necropolis]] consists of the [[Great Pyramid of Giza|Pyramid of Khufu]] (known as the ''Great Pyramid'' and the ''Pyramid of Cheops''), the somewhat smaller [[Khafre's Pyramid|Pyramid of Khafre]] (or Chephren), and the relatively modest-size [[Menkaure's Pyramid|Pyramid of Menkaure]] (or Mykerinus), along with a number of smaller satellite edifices, known as "queens" pyramids, causeways and valley pyramids, and most noticeably the [[Great Sphinx]]. Current consensus among [[Egyptology|Egyptologists]] is that the head of the Great Sphinx is that of Khafre. Associated with these royal monuments are the [[tomb]]s of high officials and much later burials and monuments (from the [[New Kingdom]] onwards), signifying | + | This [[Ancient Egypt]]ian [[necropolis]] consists of the [[Great Pyramid of Giza|Pyramid of Khufu]] (known as the ''Great Pyramid'' and the ''Pyramid of Cheops''), the somewhat smaller [[Khafre's Pyramid|Pyramid of Khafre]] (or Chephren), and the relatively modest-size [[Menkaure's Pyramid|Pyramid of Menkaure]] (or Mykerinus), along with a number of smaller satellite edifices, known as "queens" pyramids, causeways and valley pyramids, and most noticeably the [[Great Sphinx]]. Current consensus among [[Egyptology|Egyptologists]] is that the head of the Great Sphinx is that of Khafre. Associated with these royal monuments are the [[tomb]]s of high officials and much later burials and monuments (from the [[New Kingdom]] onwards), signifying reverence to those buried in the necropolis. |

Of the three, only Menkaure's Pyramid is seen today sans any of its original polished [[limestone]] casing, with Khafre's Pyramid retaining a prominent display of casing stones at its apex, while Khufu's Pyramid maintains a more limited collection at its base. It is interesting to note that this pyramid appears larger than the adjacent Khufu Pyramid by virtue of its more elevated location, and the steeper angle of inclination of its construction – it is, in fact, smaller in both height and volume. | Of the three, only Menkaure's Pyramid is seen today sans any of its original polished [[limestone]] casing, with Khafre's Pyramid retaining a prominent display of casing stones at its apex, while Khufu's Pyramid maintains a more limited collection at its base. It is interesting to note that this pyramid appears larger than the adjacent Khufu Pyramid by virtue of its more elevated location, and the steeper angle of inclination of its construction – it is, in fact, smaller in both height and volume. | ||

| − | + | {{readout||right|250px|The [[Great Pyramid]] at Giza is the last of the [[Seven Wonders of the Ancient World]] still in existence}} | |

| − | The most active phase of construction | + | The most active phase of construction was in the twenty-fifth century B.C.E.. The ancient remains of the Giza necropolis have attracted visitors and tourists since [[classical antiquity]], when these [[Old Kingdom]] monuments were already over 2,000 years old. It was popularized in [[Hellenistic civilization|Hellenistic]] times when the [[Great Pyramid]] was listed by [[Antipater of Sidon]] as one of the [[Seven Wonders of the World]]. Today it is the only one of the ancient Wonders still in existence. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Major components of the complex== | ==Major components of the complex== | ||

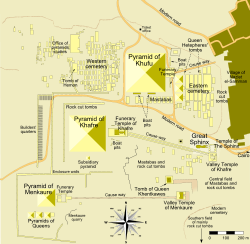

| − | [[Image:Giza pyramid complex (map).svg|thumb| | + | [[Image:Giza pyramid complex (map).svg|thumb|right|250px|Map of Giza pyramid complex]] |

| − | |||

| + | Contained in the Giza Necropolis complex are three large pyramids—the pyramids of [[Pyramids of Giza#Khufu|Khufu]] (the Great Pyramid), [[Pyramids of Giza#Pyramid of Khafre|Khafre]] and [[Pyramids of Giza#Pyramid of Menkaure|Menkaure]], the [[Pyramids of Giza#The Great Sphinx|Sphinx]], and the [[Pyramids of Giza#Khufu ship|Khufu ship]]. | ||

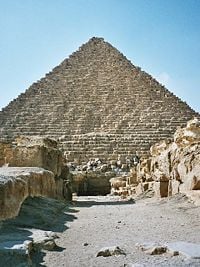

| + | [[Image:Kheops-Pyramid.jpg|thumb|250px|left|Great Pyramid of Giza.]] | ||

=== Pyramid of Khufu=== | === Pyramid of Khufu=== | ||

{{Main|Great Pyramid of Giza}} | {{Main|Great Pyramid of Giza}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

The '''Great Pyramid''' is the oldest and the largest of the three [[pyramid]]s in the [[Giza Necropolis]] bordering what is now [[Cairo]], [[Egypt]] in Africa. The only remaining member of the ancient [[Seven Wonders of the World]], it is believed to have been constructed over a 20-year period concluding around 2560 B.C.E. The Great Pyramid was built as a tomb for [[Fourth dynasty of Egypt|Fourth dynasty]] [[ancient Egypt|Egyptian]] pharaoh [[Khufu]] (Cheops), and is sometimes called '''Khufu's Pyramid''' or the '''Pyramid of Khufu'''. | The '''Great Pyramid''' is the oldest and the largest of the three [[pyramid]]s in the [[Giza Necropolis]] bordering what is now [[Cairo]], [[Egypt]] in Africa. The only remaining member of the ancient [[Seven Wonders of the World]], it is believed to have been constructed over a 20-year period concluding around 2560 B.C.E. The Great Pyramid was built as a tomb for [[Fourth dynasty of Egypt|Fourth dynasty]] [[ancient Egypt|Egyptian]] pharaoh [[Khufu]] (Cheops), and is sometimes called '''Khufu's Pyramid''' or the '''Pyramid of Khufu'''. | ||

| Line 54: | Line 42: | ||

=== Pyramid of Khafre === | === Pyramid of Khafre === | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Khafre's Pyramid343.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Khafre's Pyramid]] | |

| − | [[Image:Khafre's Pyramid343.jpg|thumb|right| | + | [[Khafre]]'s Pyramid, is the second largest of the [[ancient Egypt]]ian Giza pyramid complex and the tomb of the [[fourth dynasty of Egypt|fourth-dynasty]] [[pharaoh]] Khafre (also spelled Khafra or Chephren). |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The pyramid has a base length of 215 meters (705 feet) and rises to a height of 143.5 meters (471 feet). The slope of the pyramid rises at an 53° 10' | + | The pyramid has a base length of 215 meters (705 feet) and rises to a height of 143.5 meters (471 feet). The slope of the pyramid rises at an angle 53° 10', steeper than its neighbor Khufu’s pyramid which has an angle of 51°50'40." The pyramid sits on bedrock 10 meters (33 feet) higher than Khufu’s pyramid which would make it look taller. |

The pyramid was likely opened and robbed during the First Intermediate Period. During the eighteenth dynasty the overseer of temple construction robbed casing stone from it to build a temple in Heliopolis on [[Ramesses II]]’s orders. Arab historian [[Ibn Abd as-Salaam]] recorded that the pyramid was opened in 1372. It was first explored in modern times by [[Giovanni Belzoni]] in 1818, and the first complete exploration was conducted by [[John Perring]] in 1837. | The pyramid was likely opened and robbed during the First Intermediate Period. During the eighteenth dynasty the overseer of temple construction robbed casing stone from it to build a temple in Heliopolis on [[Ramesses II]]’s orders. Arab historian [[Ibn Abd as-Salaam]] recorded that the pyramid was opened in 1372. It was first explored in modern times by [[Giovanni Belzoni]] in 1818, and the first complete exploration was conducted by [[John Perring]] in 1837. | ||

Like the Great Pyramid, built by Khafre’s father Khufu, a rock outcropping was used in the core. Due to the slope of the plateau, the northwest corner was cut 10 meters (33 feet) out of the rock subsoil and the southeast corner is built up. | Like the Great Pyramid, built by Khafre’s father Khufu, a rock outcropping was used in the core. Due to the slope of the plateau, the northwest corner was cut 10 meters (33 feet) out of the rock subsoil and the southeast corner is built up. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The pyramid was surrounded by a terrace 10 meters (33 feet) wide paved with irregular limestone slabs behind a large perimeter wall. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Along the centerline of the pyramid on the south side was a satellite pyramid, but almost nothing remains other than some core blocks and the outline of the foundation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To the east of the Pyramid sat the mortuary temple. It is larger than previous temples and is the first to include all five standard elements of later mortuary temples: an entrance hall, a columned court, five niches for statues of the pharaoh, five storage chambers, and an inner sanctuary. There were over 52 life size statues of Khafre, but these were removed and recycled, possibly by Ramesses II. The temple was built of megalithic blocks, but it is now largely in ruins. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A causeway runs 494.6 meters to the valley temple. The valley temple is very similar to the mortuary temple. The valley temple is built of megalithic blocks sheathed in red granite. The square pillars of the T shaped hallway were made of solid granite and the floor was paved in [[alabaster]]. There are sockets in the floor that would have fixed 23 statues of Khafre, but these have since been plundered. The mortuary temple is remarkably well preserved. | ||

====Inside the pyramid==== | ====Inside the pyramid==== | ||

| − | |||

Two entrances lead to the burial chamber, one that opens 11.54 meters (38 feet) up the face of the pyramid and one that opens at the base of the pyramid. These passageways do not align with the centerline of the pyramid, but are offset to the east by 12 meters (39 feet). The lower descending passageway is carved completely out of the bedrock, descending, running horizontal, then ascending to join the horizontal passage leading to the burial chamber. | Two entrances lead to the burial chamber, one that opens 11.54 meters (38 feet) up the face of the pyramid and one that opens at the base of the pyramid. These passageways do not align with the centerline of the pyramid, but are offset to the east by 12 meters (39 feet). The lower descending passageway is carved completely out of the bedrock, descending, running horizontal, then ascending to join the horizontal passage leading to the burial chamber. | ||

| Line 74: | Line 67: | ||

The burial chamber was carved out of a pit in the bedrock. The roof is constructed of gabled [[limestone]] beams. The chamber is rectangular, 14.15 meters by 5 meters, and is oriented east-west. Khafre’s [[sarcophagus]] was carved out of a solid block of granite and sunk partially in the floor. Another pit in the floor likely contained the canopic chest. | The burial chamber was carved out of a pit in the bedrock. The roof is constructed of gabled [[limestone]] beams. The chamber is rectangular, 14.15 meters by 5 meters, and is oriented east-west. Khafre’s [[sarcophagus]] was carved out of a solid block of granite and sunk partially in the floor. Another pit in the floor likely contained the canopic chest. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=== Pyramid of Menkaure === | === Pyramid of Menkaure === | ||

| Line 95: | Line 78: | ||

=== Great Sphinx === | === Great Sphinx === | ||

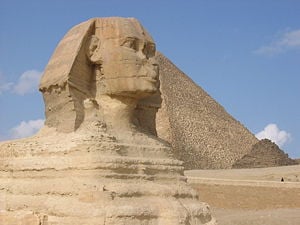

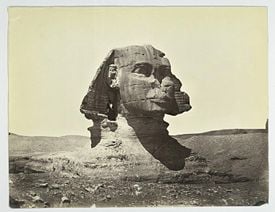

| − | + | [[Image:Great Sphinx Closeup.JPG|left|300px|thumb|The Great Sphinx at Giza, Egypt]] | |

| − | [[Image:Great Sphinx Closeup.JPG| | ||

The '''Great Sphinx of Giza''' is a large half-human, half-lion [[Sphinx]] statue in [[Egypt]], on the [[Giza Plateau]] at the west bank of the [[Nile|Nile River]], near modern-day [[Cairo]]. It is one of the largest single-stone statues on Earth, and is commonly believed to have been built by [[ancient Egyptians]] in the third millennium B.C.E.. | The '''Great Sphinx of Giza''' is a large half-human, half-lion [[Sphinx]] statue in [[Egypt]], on the [[Giza Plateau]] at the west bank of the [[Nile|Nile River]], near modern-day [[Cairo]]. It is one of the largest single-stone statues on Earth, and is commonly believed to have been built by [[ancient Egyptians]] in the third millennium B.C.E.. | ||

| − | What name ancient Egyptians called the statue is not completely known. The commonly used name “[[Sphinx]]” was given to it in [[Classical antiquity|Antiquity]] based on the [[Greek mythology|legendary Greek]] creature with the body of a [[lion]], the head of a woman and the wings of an [[eagle]], though Egyptian sphinxes have the head of a man. The word “sphinx” comes from the Greek | + | What name ancient Egyptians called the statue is not completely known. The commonly used name “[[Sphinx]]” was given to it in [[Classical antiquity|Antiquity]] based on the [[Greek mythology|legendary Greek]] creature with the body of a [[lion]], the head of a woman and the wings of an [[eagle]], though Egyptian sphinxes have the head of a man. The word “sphinx” comes from the Greek Σφινξ—Sphinx, apparently from the verb σφινγω—''sphingo'', meaning “to strangle,” as the sphinx from Greek mythology strangled anyone incapable of answering her riddle. A few, however, have postulated it to be a corruption of the ancient [[Egyptian language|Egyptian]] ''Shesep-ankh,'' a name applied to royal statues in the [[Fourth dynasty of Egypt|Fourth Dynasty]], though it came to be more specifically associated with the Great Sphinx in the [[New Kingdom]]. In medieval texts, the names ''balhib'' and ''bilhaw'' referring to the Sphinx are attested, including by Egyptian historian [[Maqrizi]], which suggest [[Coptic language|Coptic]] constructions, but the [[Egyptian Arabic]] name ''Abul-Hôl,'' which translates as “Father of Terror,” came to be more widely used. |

[[Image:GreatSphinx1867.jpg|thumb|right|275px|The Great Sphinx in 1867. Note its unrestored original condition, still partially buried body, and a man standing beneath its ear.]] | [[Image:GreatSphinx1867.jpg|thumb|right|275px|The Great Sphinx in 1867. Note its unrestored original condition, still partially buried body, and a man standing beneath its ear.]] | ||

| − | The Great Sphinx is a statue with the face of a man and the body of a [[lion]]. Carved out of the surrounding [[limestone]] bedrock, it is 57 meters (185 feet) long, 6 meters (20 feet) wide, and has a height of 20 meters (65 feet), making it the largest single-stone statue in the world. Blocks of stone weighing upwards of 200 [[ton]]s were quarried in the construction phase to build the adjoining Sphinx Temple. It is located on the west bank of the [[Nile|Nile River]] within the confines of the | + | The Great Sphinx is a statue with the face of a man and the body of a [[lion]]. Carved out of the surrounding [[limestone]] bedrock, it is 57 meters (185 feet) long, 6 meters (20 feet) wide, and has a height of 20 meters (65 feet), making it the largest single-stone statue in the world. Blocks of stone weighing upwards of 200 [[ton]]s were quarried in the construction phase to build the adjoining Sphinx Temple. It is located on the west bank of the [[Nile|Nile River]] within the confines of the Giza pyramid field. The Great Sphinx faces due east, with a small temple between its paws. |

====Restoration==== | ====Restoration==== | ||

| − | + | After the Giza [[necropolis]] was abandoned, the Sphinx became buried up to its shoulders in sand. The first attempt to dig it out dates back to 1400 B.C.E., when the young [[Thutmose IV|Tutmosis IV]] formed an excavation party which, after much effort, managed to dig the front paws out. Tutmosis IV had a [[granite]] [[Stele|stela]] known as the "[[Dream Stela]]" placed between the paws. The stela reads, in part: | |

| − | After the [[ | + | <blockquote>… the royal son, Thothmos, having been arrived, while walking at midday and seating himself under the shadow of this mighty god, was overcome by slumber and slept at the very moment when [[Ra]] is at the summit (of heaven). He found that the Majesty of this august god spoke to him with his own mouth, as a father speaks to his son, saying: Look upon me, contemplate me, O my son Thothmos; I am thy father, [[Harmakhis]]-[[Khepri|Khopri]]-Ra-[[Atum|Tum]]; I bestow upon thee the sovereignty over my domain, the supremacy over the living … Behold my actual condition that thou mayest protect all my perfect limbs. The sand of the desert whereon I am laid has covered me. Save me, causing all that is in my heart to be executed.<ref>[http://www.harmakhis.org/The%20Stele%20of%20Thotmes%20IV%20%28Translation%29.htm The Stele of Thotmes IV] A Translation by D. Mallet. Retrieved July 24, 2007.</ref></blockquote> |

| − | |||

| − | <blockquote> | ||

[[Ramesses II]] may have also performed restoration work on the Sphinx. | [[Ramesses II]] may have also performed restoration work on the Sphinx. | ||

It was in 1817 that the first modern dig, supervised by [[Giovanni Battista Caviglia|Captain Caviglia]], uncovered the Sphinx’s chest completely. The entirety of the Sphinx was finally dug out in 1925. | It was in 1817 that the first modern dig, supervised by [[Giovanni Battista Caviglia|Captain Caviglia]], uncovered the Sphinx’s chest completely. The entirety of the Sphinx was finally dug out in 1925. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The one-meter-wide [[nose]] on the face is missing. A legend that the nose was broken off by a cannon ball fired by [[Napoleon I of France|Napoléon]]’s soldiers still survives, as do diverse variants indicting [[Great Britain|British]] troops, [[Mamluk]]s, and others. However, sketches of the Sphinx by [[Frederic Louis Norden|Frederick Lewis Norden]] made in 1737 and published in 1755 illustrate the Sphinx without a nose. The Egyptian historian [[al-Maqrizi]], writing in the fifteenth century, attributes the vandalism to Muhammad Sa'im al-Dahr, a [[Sufi]] [[Fanaticism|fanatic]] from the [[Khaneqah|khanqah]] of Sa'id al-Su'ada. In 1378, upon finding the Egyptian peasants making offerings to the Sphinx in the hope of increasing their harvest, Sa'im al-Dahr was so outraged that he destroyed the nose. Al-Maqrizi describes the Sphinx as the “[[Nile]] talisman” on which the locals believed the cycle of inundation depended. | |

| − | + | In addition to the lost nose, a ceremonial pharaonic beard is thought to have been attached, although this may have been added in later periods after the original construction. [[Egyptologist]] Rainer Stadelmann has posited that the rounded divine beard may not have existed in the Old or Middle Kingdoms, only being conceived of in the [[New Kingdom]] to identify the Sphinx with the god Horemakhet. This may also relate to the later fashion of pharaohs, which was to wear a plaited beard of authority—a false beard (chin straps are actually visible on some statues), since Egyptian culture mandated that men be clean shaven. Pieces of this beard are today kept in the [[British Museum]] and the [[Egyptian Museum]]. | |

====Mythology==== | ====Mythology==== | ||

| Line 132: | Line 102: | ||

====Origin and identity==== | ====Origin and identity==== | ||

| + | [[Image:Egypt.Giza.Sphinx.02.jpg|290px|thumb|The Sphinx against Khafra’s pyramid]] | ||

| + | The Great Sphinx is one of the world’s largest and oldest [[statue]]s, yet basic facts about it such as the real-life model for the face, when it was built, and by whom, are debated. These questions have collectively earned the title “Riddle of the Sphinx,” a nod to its Greek namesake, although this phrase should not be confused with the original [[Sphinx#Greek sphinx|Greek legend]]. | ||

| − | + | Many of the most prominent early [[Egyptology|Egyptologists]] and excavators of the Giza plateau believed the Sphinx and its neighboring temples to pre-date the fourth dynasty, the period including [[pharoah]]s [[Khufu]] (Cheops) and his son [[Khafre]] (Chephren). British Egyptologist [[E. A. Wallis Budge]] (1857–1934) stated in his 1904 book ''Gods of the Egyptians'': | |

| + | <blockquote>This marvelous object [the Great Sphinx] was in existence in the days of Khafre, or Khephren, and it is probable that it is a very great deal older than his reign and that it dates from the end of the archaic period.</blockquote> | ||

| − | + | French Egyptologist and Director General of Excavations and Antiquities for the Egyptian government, [[Gaston Maspero]] (1846–1916), surveyed the Sphinx in the 1920s and asserted: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>The Sphinx stela shows, in line thirteen, the cartouche of Khephren. I believe that to indicate an excavation carried out by that prince, following which, the almost certain proof that the Sphinx was already buried in sand by the time of Khafre and his predecessors.<ref>[http://www.theglobaleducationproject.org/egypt/articles/phototr3.html The Sphinx - Some History]''www.theglobaleducationproject.org''. Retrieved July 30, 2007.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | <blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Later researchers, though, concluded that the Great Sphinx represented the likeness of Khafre, who also became credited as the builder. This would place the time of construction somewhere between 2520 B.C.E. and 2494 B.C.E. | |

| − | + | Attribution of the Sphinx to Khafre is based on the "Dream [[Stela]]" erected between the paws of the Sphinx by [[Pharaoh]] [[Thutmose IV]] in the [[New Kingdom]]. Egyptologist [[Henry Salt]] (1780–1827) made a copy of this damaged stela before further damage occurred destroying this part of the text. The last line still legible as recorded by Salt bore the syllable "Khaf," which was assumed to refer to Khafre, particularly because it was enclosed in a [[cartouche]], the line enclosing [[Egyptian hieroglyph|hieroglyph]]s for a king or god. When discovered, however, the lines of text were incomplete, only referring to a “Khaf,” and not the full “Khafre.” The missing syllable “ra” was later added to complete the translation by [[Thomas Young]], on the assumption that the text referred to “Khafre.” Young’s interpretation was based on an earlier facsimile in which the translation reads as follows: | |

| + | <blockquote>… which we bring for him: oxen… and all the young vegetables; and we shall give praise to Wenofer … Khaf … the statue made for Atum-Hor-em-Akhet.<ref>Jason Colavito, [http://jcolavito.tripod.com/lostcivilizations/id17.html Who Built the Sphinx?]. Retrieved July 30, 2007.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Regardless of the translation, the stela offers no clear record of in what context the name Khafre was used in relation to the Sphinx – as the builder, restorer, or otherwise. The lines of text referring to Khafre flaked off and were destroyed when the Stela was re-excavated in the early 1900s. | |

| − | + | In contrast, the “Inventory Stela” (believed to date from the twenty-sixth dynasty 664-525 B.C.E.) found by [[Auguste Mariette]] on the Giza plateau in 1857, describes how Khufu (the father of Khafre, the alleged builder) discovered the damaged monument buried in sand, and attempted to excavate and repair the dilapidated Sphinx. If accurate, this would date the Sphinx to a much earlier time. However, due to the late dynasty origin of the document, and the use of names for deities that belong to the Late Period, this text from the Inventory Stela is often dismissed by Egyptologists as late dynasty historical revisionism.<ref name=Reader>Colin Reader, | |

| + | [http://www.gizabuildingproject.com/art_reader1.php Giza Before the Fourth Dynasty] ''Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum'' (JACF) 9 (2002): 5-21. Retrieved July 30, 2007.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Traditionally, the evidence for dating the Great Sphinx has been based primarily on fragmented summaries of early [[Christian]] writings gleaned from the work of the [[Hellenistic Period]] Egyptian priest Manethô, who compiled the now lost revisionist Egyptian history ''Aegyptika.'' These works, and to a lesser degree, earlier Egyptian sources, such as the “Turin Canon” and “Table of Abydos” among others, combine to form the main body of historical reference for Egyptologists, giving a consensus for a timeline of rulers known as the “King’s List,” found in the reference archive; the ''Cambridge Ancient History.''<ref>[http://www.phouka.com/pharaoh/egypt/history/00kinglists.html King Lists]. ''www.phouka.com''. Retrieved July 30, 2007.</ref><ref>[http://www.friesian.com/notes/oldking.htm Index of Egyptian History] Retrieved July 30, 2007.</ref> As a result, since Egyptologists have ascribed the Sphinx to Khafre, establishing the time he reigned would date the monument as well. | |

| − | |||

| − | <ref | ||

| − | [http://www. | ||

| − | + | This position regards the context of the Sphinx as residing within part of the greater funerary complex credited to Khafre, which includes the Sphinx and Valley Temples, a causeway, and second pyramid.<ref>Ancient Egypt Research Associates (AERA) [http://www.aeraweb.org/khafre_structures.asp Khafre’s Monuments as a Unit] Sphinx Project. Retrieved February 27, 2008. </ref> Both temples display the same architectural style employing stones weighing up to 200 tons. This suggests that the temples, along with the Sphinx, were all part of the the same quarry and construction process. | |

| − | In 2004, French Egyptologist [[Vassil Dobrev]] announced the results of a twenty-year reexamination of historical records, and uncovering of new evidence that suggests the Great Sphinx may have been the work of the little known Pharaoh [[Djedefre]], Khafre’s half brother and a son of [[Khufu]], the builder of the [[Great Pyramid of Giza]]. Dobrev suggests it was built by Djedefre in the image of his father Khufu, identifying him with the sun god [[Ra]] in order to restore respect for their dynasty.<ref>[http://news.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2004/12/14/wsphinx14.xml “I have solved riddle of the Sphinx, says Frenchman”] '' | + | In 2004, French Egyptologist [[Vassil Dobrev]] announced the results of a twenty-year reexamination of historical records, and uncovering of new evidence that suggests the Great Sphinx may have been the work of the little known Pharaoh [[Djedefre]], Khafre’s half brother and a son of [[Khufu]], the builder of the [[Great Pyramid of Giza]]. Dobrev suggests it was built by Djedefre in the image of his father Khufu, identifying him with the sun god [[Ra]] in order to restore respect for their dynasty.<ref>Nic Fleming, [http://news.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2004/12/14/wsphinx14.xml “I have solved riddle of the Sphinx, says Frenchman”], Dec. 14, 2004, ''The Daily Telegraph''. Retrieved June 28, 2005.</ref> He supports this by suggesting that Khafre’s causeway was built to conform to a pre-existing structure, which he concludes, given its location, could only have been the Sphinx.<ref name=Reader/> |

| − | + | These later efforts notwithstanding, the limited evidence giving provenance to Khafre (or his brother) remains ambiguous and circumstantial. As a result, the determination of who built the Sphinx, and when, continues to be the subject of debate. As Selim Hassan stated in his report regarding his excavation of the Sphinx enclosure back in the 1940s: | |

| + | <blockquote>Taking all things into consideration, it seems that we must give the credit of erecting this, the world’s most wonderful statue, to Khafre, but always with this reservation that there is not one single contemporary inscription which connects the Sphinx with Khafre, so sound as it may appear, we must treat the evidence as circumstantial, until such time as a lucky turn of the spade of the excavator will reveal to the world a definite reference to the erection of the Sphinx.<ref name=Reader/></blockquote> | ||

=== Khufu ship === | === Khufu ship === | ||

| − | |||

[[Image:Barque Solaire2.JPG|thumb|250px|The reconstructed "Solar barge" of Khufu]] | [[Image:Barque Solaire2.JPG|thumb|250px|The reconstructed "Solar barge" of Khufu]] | ||

The '''Khufu ship''' is an intact full-size vessel from [[Ancient Egypt]] that was sealed into a pit in the [[Giza pyramid complex]] at the foot of the [[Great Pyramid of Giza]] around 2,500 B.C.E. The ship was almost certainly built for [[Khufu]] (King Cheops), the second pharaoh of the [[Fourth dynasty of Egypt|Fourth Dynasty]] of the [[Old Kingdom]] of Egypt. | The '''Khufu ship''' is an intact full-size vessel from [[Ancient Egypt]] that was sealed into a pit in the [[Giza pyramid complex]] at the foot of the [[Great Pyramid of Giza]] around 2,500 B.C.E. The ship was almost certainly built for [[Khufu]] (King Cheops), the second pharaoh of the [[Fourth dynasty of Egypt|Fourth Dynasty]] of the [[Old Kingdom]] of Egypt. | ||

| − | It is one of the oldest, largest, and best-preserved vessels from antiquity. At 43.6 m overall, it is longer than the reconstructed Ancient Greek trireme [[Olympias (trireme)|''Olympias'']] and, for comparison, nine metres longer than the ''[[Golden Hind]]'' in which Francis Drake circumnavigated the world. | + | It is one of the oldest, largest, and best-preserved vessels from antiquity. At 43.6 m overall, it is longer than the reconstructed Ancient Greek trireme [[Olympias (trireme)|''Olympias'']] and, for comparison, nine metres longer than the ''[[Golden Hind]]'' in which [[Francis Drake]] circumnavigated the world. |

The ship was rediscovered in 1954 by Kamal el-Mallakh, undisturbed since it was sealed into a pit carved out of the Giza bedrock. It was built largely of [[cedar]] planking in the "shell-first" construction technique and has been reconstructed from more than 1,200 pieces which had been laid in a logical, disassembled order in the pit beside the pyramid. | The ship was rediscovered in 1954 by Kamal el-Mallakh, undisturbed since it was sealed into a pit carved out of the Giza bedrock. It was built largely of [[cedar]] planking in the "shell-first" construction technique and has been reconstructed from more than 1,200 pieces which had been laid in a logical, disassembled order in the pit beside the pyramid. | ||

| Line 173: | Line 144: | ||

==Alternative theories== | ==Alternative theories== | ||

| − | In common with many famous constructions of remote antiquity, the Pyramids of Giza and the Great Sphinx have been the subject of numerous speculative theories and assertions by non-[[Egyptology|specialists]], [[mysticism|mystics]], [[pseudohistory|pseudohistorians]], [[pseudoarchaeology|pseudoarchaeologists]], and general writers. These alternative theories of the origin, purpose and history of the monument typically invoke a wide array of sources and associations, such as neighboring cultures, [[astrology]], [[Lost Lands|lost continents]] and civilizations (such as [[Atlantis]]), [[numerology]], [[mythology]] and other [[esotericism|esoteric]] subjects. | + | In common with many famous constructions of remote antiquity, the Pyramids of Giza and the Great Sphinx have been the subject of numerous speculative theories and assertions by non-[[Egyptology|specialists]], [[mysticism|mystics]], [[pseudohistory|pseudohistorians]], [[pseudoarchaeology|pseudoarchaeologists]], and general writers. These alternative theories of the origin, purpose, and history of the monument typically invoke a wide array of sources and associations, such as neighboring cultures, [[astrology]], [[Lost Lands|lost continents]] and civilizations (such as [[Atlantis]]), [[numerology]], [[mythology]] and other [[esotericism|esoteric]] subjects. |

| − | One well-publicized debate was generated by the works of two writers, [[Graham Hancock]] and [[Robert Bauval]], in a series of separate and collaborative publications from the late 1980s onwards.<ref>[http://www.bbc.co.uk/science/horizon/2000/atlantisrebornagain.shtml Atlantis Reborn Again] BBC Horizon programme (2000) on alternate theories of Hancock and Bauval. Retrieved July 30, 2007.</ref> Their claims include that the construction of the Great Sphinx and the monument at [[Tiwanaku]] in modern [[Bolivia]] was begun in 10,500 B.C.E.; that the Sphinx's [[lion]]-shape is a definitive reference to the [[constellation]] of [[Leo (constellation)|Leo]]; and that the layout and orientation of the Sphinx, the Giza pyramid complex and the [[Nile|Nile River]] is an accurate reflection or “map” of the constellations of Leo, [[Orion (constellation)|Orion]] (specifically, Orion’s Belt) and the [[Milky Way]], respectively. | + | One well-publicized debate was generated by the works of two writers, [[Graham Hancock]] and [[Robert Bauval]], in a series of separate and collaborative publications from the late 1980s onwards.<ref>[http://www.bbc.co.uk/science/horizon/2000/atlantisrebornagain.shtml Atlantis Reborn Again] BBC Horizon programme (2000) on alternate theories of Hancock and Bauval. Retrieved July 30, 2007.</ref> Their claims include that the construction of the Great Sphinx and the monument at [[Tiwanaku]] near [[Lake Titicaca]] in modern [[Bolivia]] was begun in 10,500 B.C.E.; that the Sphinx's [[lion]]-shape is a definitive reference to the [[constellation]] of [[Leo (constellation)|Leo]]; and that the layout and orientation of the Sphinx, the Giza pyramid complex and the [[Nile|Nile River]] is an accurate reflection or “map” of the constellations of Leo, [[Orion (constellation)|Orion]] (specifically, Orion’s Belt) and the [[Milky Way]], respectively. |

| − | + | Although universally regarded by mainstream [[archaeology|archaeologists]] and [[Egyptology|Egyptologists]] as a form of [[pseudoscience]],<ref>Mark Lehner, ''The Complete Pyramids – Solving the Ancient Mysteries'' (London: Thames & Hudson, 1997, ISBN 0500050848).</ref> [[Robert Bauval]] and [[Adrian Gilbert]] (1994) proposed that the three main pyramids at Giza form a pattern on the ground that is virtually identical to that of the three belt stars of the [[Orion (constellation)|Orion]] constellation. Using computer software, they wound back the Earth's skies to ancient times, and witnessed a 'locking-in' of the mirror image between the pyramids and the stars at the same time as Orion reached a turning point at the bottom of its [[precession]]al shift up and down the [[meridian (astronomy)|meridian]]. This [[conjunction (astronomy)|conjunction]], they claimed, was exact, and it occurred precisely at the date 10,450 B.C.E.. And they claim that Orion is "West" of the [[Milky Way]], in proportion to Giza and the Nile.<ref>Graham Hancock, and Santha Faiia. ''Heaven's Mirror.'' 1998.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Their theories, and the [[astronomy|astronomical]] and archaeological data upon which they are based, have received refutations by some mainstream scholars who have examined them, notably the astronomers [[Ed Krupp]] and [[Anthony Fairall]].<ref>Tony Fairall [http://www.antiquityofman.com/Orion_Fairall.html Precession and the layout of the Ancient Egyptian pyramids] (June 1999, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society) Retrieved July 30, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | Their theories, and the [[astronomy|astronomical]] and archaeological data upon which they are based, have received refutations by some mainstream scholars who have examined them, notably the astronomers [[Ed Krupp]] and [[Anthony Fairall]].<ref>Tony Fairall [http://www.antiquityofman.com/Orion_Fairall.html Precession and the layout of the Ancient Egyptian pyramids] (June 1999, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society) Retrieved July 30, 2007.</ref> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Tourism== | ==Tourism== | ||

| + | The [[Great Pyramid of Giza]] is one of the [[seven wonders of the ancient world]], the only one still standing. Together with the other pyramids and the [[Great Sphinx]], the site attracts thousands of tourists every year. Due largely to nineteenth-century images, the pyramids of Giza are generally thought of by foreigners as lying in a remote, desert location, even though they are located close to the highly populated city of [[Cairo]].<ref>Audrey DeLange and George DeLange, [http://www.delange.org/Giza_Pyramids_Sphinx/EP3.htm Giza Sphinx & Pyramids,] The DeLange Home Page. Retrieved March 29, 2009.</ref> Urban development reaches right up to the perimeter of the antiquities site. Egypt offers tourists more than antiquities, with nightlife, fine dining, snorkeling, and swimming in the [[Mediterranean Sea]]. | ||

| − | + | The ancient sites in the [[Memphis, Egypt|Memphis]] area, including those at Giza, together with those at [[Saqqara]], [[Dahshur]], [[Abu Ruwaysh]], and [[Abusir]], were collectively declared a [[World Heritage Site]] in 1979.<ref> [http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/86 Memphis and its Necropolis – the Pyramid Fields from Giza to Dahshur] ''UNESCO''. Retrieved July 30, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | The ancient sites in the [[Memphis, Egypt|Memphis]] area, including those at Giza, together with those at [[Saqqara]], [[Dahshur]], [[Abu Ruwaysh]], and [[Abusir]], were collectively declared a [[World Heritage Site]] in 1979.<ref> [http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/86 Memphis and its Necropolis – the Pyramid Fields from Giza to Dahshur] Retrieved July 30, 2007.</ref> | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 198: | Line 161: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *Lehner, | + | *Hancock, Graham, and Santha Faiia. ''Heaven's Mirror: Quest for the Lost Civilization''. Three Rivers Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0609804773 |

| − | *Manley, Bill | + | *Jenkins, Nancy. ''The Boat beneath the Pyramid: King Cheops' Royal Ship.'' Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1980. ISBN 0030570611 |

| − | *"'' | + | *Lehner, Mark. ''The Complete Pyramids – Solving the Ancient Mysteries.'' London: Thames & Hudson, 1997. ISBN 0500050848 |

| − | * Reisner, George | + | *Lipke, Paul. ''The Royal Ship of Cheops: A Retrospective Account of the Discovery, Restoration and Reconstruction. Based on interviews with Hag Ahmed Youssef Moustafa.'' Oxford: B.A.R., 1984. ISBN 0860542939 |

| − | * | + | *Manley, Bill. ''The Seventy Great Mysteries of Ancient Egypt.'' Thames & Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500051232 |

| − | + | *Reader, Colin. "Giza Before the Fourth Dynasty" ''Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum'' (JACF) 9 (2002): 5-21 | |

| − | + | *Reisner, George. ''A History of the Giza Necropolis, Volume 1.'' Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1942. ISBN 0674402502 | |

| − | + | *Verner, Miroslav. ''The Pyramids – Their Archaeology and History.'' Atlantic Books, 2001. ISBN 1843541718 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved December 6, 2022. | |

| − | + | *[http://local.live.com/default.aspx?v=2&cp=29.978506~31.134739&style=h&lvl=13 Aerial view of Giza pyramids at Windows Live Local] | |

| − | *[http://local.live.com/default.aspx?v=2&cp=29.978506~31.134739&style=h&lvl=13 Aerial view of Giza pyramids at Windows Live Local] | + | *[http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ancient/explore-ancient-egypt.html Explore Ancient Egypt] NOVA. |

| − | + | *[http://guardians.net/egypt/sphinx/ Sphinx photo gallery] | |

| − | + | *[http://www.catchpenny.org/nose.html The Sphinx’s Nose] | |

| − | *[http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ | + | * [http://www.guardians.net/hawass/pbuildrs.htm Pyramid Construction: New Evidence Discovered at Giza] by Zahi Hawass, director of the Giza Pyramids and Saqqara. Guardian’s Egypt. |

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | * [http:// | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *[http://www.catchpenny.org/nose.html The Sphinx’s Nose] | ||

| − | *[http://guardians.net/ | ||

| − | |||

{{Credits|Giza_pyramid_complex|135399652|Khafre's_Pyramid|132307852|Menkaure's_Pyramid|133050319|Great_Sphinx_of_Giza|135371381|Khufu_ship|133958921|}} | {{Credits|Giza_pyramid_complex|135399652|Khafre's_Pyramid|132307852|Menkaure's_Pyramid|133050319|Great_Sphinx_of_Giza|135371381|Khufu_ship|133958921|}} | ||

Latest revision as of 03:38, 7 December 2022

| Memphis and its Necropolis - the Pyramid Fields from Giza to Dahshur* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, vi |

| Reference | 86 |

| Region** | Arab States |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

The Giza Necropolis stands on the Giza Plateau, on the outskirts of Cairo, Egypt. This complex of ancient monuments is located some eight kilometers (5 miles) inland into the desert from the old town of Giza on the Nile, some 25 kilometres (12.5 miles) southwest of Cairo city center.

The complex contains three large pyramids, the most famous of which, the Great Pyramid was built for the pharaoh Khufu and is possibly the largest building ever erected on the planet, and the last member of the ancient Seven Wonders of the World. The other two pyramids, each impressive in their own right, were built for the kings Khafre and Menkaure. The site also contains the Sphinx, a monstrous statue of a part-lion, part-human, mysterious both in appearance and in its origin and purpose, and the Khufu Ship, the relic of a boat built to transport Khufu to the afterlife.

This necropolis, an amazing collection of buildings that were constructed to house the dead, reveals much about the civilization of ancient Egypt. Scientists continue to research and theorize about how and why they were constructed, and their true meaning to those who initiated them. For the general public, though, the sense of wonder and respect that they command may be sufficient.

Description

This Ancient Egyptian necropolis consists of the Pyramid of Khufu (known as the Great Pyramid and the Pyramid of Cheops), the somewhat smaller Pyramid of Khafre (or Chephren), and the relatively modest-size Pyramid of Menkaure (or Mykerinus), along with a number of smaller satellite edifices, known as "queens" pyramids, causeways and valley pyramids, and most noticeably the Great Sphinx. Current consensus among Egyptologists is that the head of the Great Sphinx is that of Khafre. Associated with these royal monuments are the tombs of high officials and much later burials and monuments (from the New Kingdom onwards), signifying reverence to those buried in the necropolis.

Of the three, only Menkaure's Pyramid is seen today sans any of its original polished limestone casing, with Khafre's Pyramid retaining a prominent display of casing stones at its apex, while Khufu's Pyramid maintains a more limited collection at its base. It is interesting to note that this pyramid appears larger than the adjacent Khufu Pyramid by virtue of its more elevated location, and the steeper angle of inclination of its construction – it is, in fact, smaller in both height and volume.

The most active phase of construction was in the twenty-fifth century B.C.E.. The ancient remains of the Giza necropolis have attracted visitors and tourists since classical antiquity, when these Old Kingdom monuments were already over 2,000 years old. It was popularized in Hellenistic times when the Great Pyramid was listed by Antipater of Sidon as one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Today it is the only one of the ancient Wonders still in existence.

Major components of the complex

Contained in the Giza Necropolis complex are three large pyramids—the pyramids of Khufu (the Great Pyramid), Khafre and Menkaure, the Sphinx, and the Khufu ship.

Pyramid of Khufu

The Great Pyramid is the oldest and the largest of the three pyramids in the Giza Necropolis bordering what is now Cairo, Egypt in Africa. The only remaining member of the ancient Seven Wonders of the World, it is believed to have been constructed over a 20-year period concluding around 2560 B.C.E. The Great Pyramid was built as a tomb for Fourth dynasty Egyptian pharaoh Khufu (Cheops), and is sometimes called Khufu's Pyramid or the Pyramid of Khufu.

The structure is estimated to contain some 2.4 million stone blocks each weighing 2.5 tons, with others used for special functions deep within the pyramid weighing considerably more.

Pyramid of Khafre

Khafre's Pyramid, is the second largest of the ancient Egyptian Giza pyramid complex and the tomb of the fourth-dynasty pharaoh Khafre (also spelled Khafra or Chephren).

The pyramid has a base length of 215 meters (705 feet) and rises to a height of 143.5 meters (471 feet). The slope of the pyramid rises at an angle 53° 10', steeper than its neighbor Khufu’s pyramid which has an angle of 51°50'40." The pyramid sits on bedrock 10 meters (33 feet) higher than Khufu’s pyramid which would make it look taller.

The pyramid was likely opened and robbed during the First Intermediate Period. During the eighteenth dynasty the overseer of temple construction robbed casing stone from it to build a temple in Heliopolis on Ramesses II’s orders. Arab historian Ibn Abd as-Salaam recorded that the pyramid was opened in 1372. It was first explored in modern times by Giovanni Belzoni in 1818, and the first complete exploration was conducted by John Perring in 1837.

Like the Great Pyramid, built by Khafre’s father Khufu, a rock outcropping was used in the core. Due to the slope of the plateau, the northwest corner was cut 10 meters (33 feet) out of the rock subsoil and the southeast corner is built up.

The pyramid was surrounded by a terrace 10 meters (33 feet) wide paved with irregular limestone slabs behind a large perimeter wall.

Along the centerline of the pyramid on the south side was a satellite pyramid, but almost nothing remains other than some core blocks and the outline of the foundation.

To the east of the Pyramid sat the mortuary temple. It is larger than previous temples and is the first to include all five standard elements of later mortuary temples: an entrance hall, a columned court, five niches for statues of the pharaoh, five storage chambers, and an inner sanctuary. There were over 52 life size statues of Khafre, but these were removed and recycled, possibly by Ramesses II. The temple was built of megalithic blocks, but it is now largely in ruins.

A causeway runs 494.6 meters to the valley temple. The valley temple is very similar to the mortuary temple. The valley temple is built of megalithic blocks sheathed in red granite. The square pillars of the T shaped hallway were made of solid granite and the floor was paved in alabaster. There are sockets in the floor that would have fixed 23 statues of Khafre, but these have since been plundered. The mortuary temple is remarkably well preserved.

Inside the pyramid

Two entrances lead to the burial chamber, one that opens 11.54 meters (38 feet) up the face of the pyramid and one that opens at the base of the pyramid. These passageways do not align with the centerline of the pyramid, but are offset to the east by 12 meters (39 feet). The lower descending passageway is carved completely out of the bedrock, descending, running horizontal, then ascending to join the horizontal passage leading to the burial chamber.

One theory as to why there two entrances is that the pyramid was intended to be much larger with the northern base shifted 30 meters (98 feet) further to the north which would make the Khafre’s pyramid much larger than his father’s pyramid. This would place the entrance to lower descending passage within the masonry of the pyramid. While the bedrock is cut away further from the pyramid on the north side than on the west side, it is not clear that there is enough room on the plateau for the enclosure wall and pyramid terrace. An alternative theory is that, as with many earlier pyramids, plans were changed and the entrance was moved midway through construction.

There is a subsidiary chamber that opens to the west of the lower passage the purpose of which is uncertain. It may be used to store offerings, store burial equipment, or it may be a serdab chamber. The upper descending passage is clad in granite and descends to join with the horizontal passage to the burial chamber.

The burial chamber was carved out of a pit in the bedrock. The roof is constructed of gabled limestone beams. The chamber is rectangular, 14.15 meters by 5 meters, and is oriented east-west. Khafre’s sarcophagus was carved out of a solid block of granite and sunk partially in the floor. Another pit in the floor likely contained the canopic chest.

Pyramid of Menkaure

Menkaure's Pyramid, located on the Giza Plateau on the southwestern outskirts of Cairo, Egypt, is the smallest of the three Pyramids of Giza. It was built to serve as the tomb of the fourth dynasty Egyptian Pharaoh Menkaure.

Menkaure's Pyramid had an original height of 65.5 meters (215 feet). It now stands at 62 m (203 ft) tall with a base of 105 m (344 ft). Its angle of incline is approximately 51°20′25″. It was constructed of limestone and granite.

The pyramid's date of construction is unknown, because Menkaure's reign has not been accurately defined, but it was probably completed sometime during the twenty-sixth century B.C.E.. It lies a few hundred meters southwest of its larger neighbors, the Pyramid of Khafre and the Great Pyramid of Khufu in the Giza necropolis.

Great Sphinx

The Great Sphinx of Giza is a large half-human, half-lion Sphinx statue in Egypt, on the Giza Plateau at the west bank of the Nile River, near modern-day Cairo. It is one of the largest single-stone statues on Earth, and is commonly believed to have been built by ancient Egyptians in the third millennium B.C.E..

What name ancient Egyptians called the statue is not completely known. The commonly used name “Sphinx” was given to it in Antiquity based on the legendary Greek creature with the body of a lion, the head of a woman and the wings of an eagle, though Egyptian sphinxes have the head of a man. The word “sphinx” comes from the Greek Σφινξ—Sphinx, apparently from the verb σφινγω—sphingo, meaning “to strangle,” as the sphinx from Greek mythology strangled anyone incapable of answering her riddle. A few, however, have postulated it to be a corruption of the ancient Egyptian Shesep-ankh, a name applied to royal statues in the Fourth Dynasty, though it came to be more specifically associated with the Great Sphinx in the New Kingdom. In medieval texts, the names balhib and bilhaw referring to the Sphinx are attested, including by Egyptian historian Maqrizi, which suggest Coptic constructions, but the Egyptian Arabic name Abul-Hôl, which translates as “Father of Terror,” came to be more widely used.

The Great Sphinx is a statue with the face of a man and the body of a lion. Carved out of the surrounding limestone bedrock, it is 57 meters (185 feet) long, 6 meters (20 feet) wide, and has a height of 20 meters (65 feet), making it the largest single-stone statue in the world. Blocks of stone weighing upwards of 200 tons were quarried in the construction phase to build the adjoining Sphinx Temple. It is located on the west bank of the Nile River within the confines of the Giza pyramid field. The Great Sphinx faces due east, with a small temple between its paws.

Restoration

After the Giza necropolis was abandoned, the Sphinx became buried up to its shoulders in sand. The first attempt to dig it out dates back to 1400 B.C.E., when the young Tutmosis IV formed an excavation party which, after much effort, managed to dig the front paws out. Tutmosis IV had a granite stela known as the "Dream Stela" placed between the paws. The stela reads, in part:

… the royal son, Thothmos, having been arrived, while walking at midday and seating himself under the shadow of this mighty god, was overcome by slumber and slept at the very moment when Ra is at the summit (of heaven). He found that the Majesty of this august god spoke to him with his own mouth, as a father speaks to his son, saying: Look upon me, contemplate me, O my son Thothmos; I am thy father, Harmakhis-Khopri-Ra-Tum; I bestow upon thee the sovereignty over my domain, the supremacy over the living … Behold my actual condition that thou mayest protect all my perfect limbs. The sand of the desert whereon I am laid has covered me. Save me, causing all that is in my heart to be executed.[1]

Ramesses II may have also performed restoration work on the Sphinx.

It was in 1817 that the first modern dig, supervised by Captain Caviglia, uncovered the Sphinx’s chest completely. The entirety of the Sphinx was finally dug out in 1925.

The one-meter-wide nose on the face is missing. A legend that the nose was broken off by a cannon ball fired by Napoléon’s soldiers still survives, as do diverse variants indicting British troops, Mamluks, and others. However, sketches of the Sphinx by Frederick Lewis Norden made in 1737 and published in 1755 illustrate the Sphinx without a nose. The Egyptian historian al-Maqrizi, writing in the fifteenth century, attributes the vandalism to Muhammad Sa'im al-Dahr, a Sufi fanatic from the khanqah of Sa'id al-Su'ada. In 1378, upon finding the Egyptian peasants making offerings to the Sphinx in the hope of increasing their harvest, Sa'im al-Dahr was so outraged that he destroyed the nose. Al-Maqrizi describes the Sphinx as the “Nile talisman” on which the locals believed the cycle of inundation depended.

In addition to the lost nose, a ceremonial pharaonic beard is thought to have been attached, although this may have been added in later periods after the original construction. Egyptologist Rainer Stadelmann has posited that the rounded divine beard may not have existed in the Old or Middle Kingdoms, only being conceived of in the New Kingdom to identify the Sphinx with the god Horemakhet. This may also relate to the later fashion of pharaohs, which was to wear a plaited beard of authority—a false beard (chin straps are actually visible on some statues), since Egyptian culture mandated that men be clean shaven. Pieces of this beard are today kept in the British Museum and the Egyptian Museum.

Mythology

The Great Sphinx was believed to stand as a guardian of the Giza Plateau, where it faces the rising sun. It was the focus of solar worship in the Old Kingdom, centered in the adjoining temples built around the time of its probable construction. Its animal form, the lion, has long been a symbol associated with the sun in ancient Near Eastern civilizations. Images depicting the Egyptian king in the form of a lion smiting his enemies appear as far back as the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt. During the New Kingdom, the Sphinx became more specifically associated with the god Hor-em-akhet (Greek Harmachis) or Horus at the Horizon, which represented the Pharaoh in his role as the Shesep ankh of Atum (living image of Atum). A temple was built to the northeast of the Sphinx by King Amenhotep II, nearly a thousand years after its construction, dedicated to the cult of Horemakhet.

Origin and identity

The Great Sphinx is one of the world’s largest and oldest statues, yet basic facts about it such as the real-life model for the face, when it was built, and by whom, are debated. These questions have collectively earned the title “Riddle of the Sphinx,” a nod to its Greek namesake, although this phrase should not be confused with the original Greek legend.

Many of the most prominent early Egyptologists and excavators of the Giza plateau believed the Sphinx and its neighboring temples to pre-date the fourth dynasty, the period including pharoahs Khufu (Cheops) and his son Khafre (Chephren). British Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge (1857–1934) stated in his 1904 book Gods of the Egyptians:

This marvelous object [the Great Sphinx] was in existence in the days of Khafre, or Khephren, and it is probable that it is a very great deal older than his reign and that it dates from the end of the archaic period.

French Egyptologist and Director General of Excavations and Antiquities for the Egyptian government, Gaston Maspero (1846–1916), surveyed the Sphinx in the 1920s and asserted:

The Sphinx stela shows, in line thirteen, the cartouche of Khephren. I believe that to indicate an excavation carried out by that prince, following which, the almost certain proof that the Sphinx was already buried in sand by the time of Khafre and his predecessors.[2]

Later researchers, though, concluded that the Great Sphinx represented the likeness of Khafre, who also became credited as the builder. This would place the time of construction somewhere between 2520 B.C.E. and 2494 B.C.E.

Attribution of the Sphinx to Khafre is based on the "Dream Stela" erected between the paws of the Sphinx by Pharaoh Thutmose IV in the New Kingdom. Egyptologist Henry Salt (1780–1827) made a copy of this damaged stela before further damage occurred destroying this part of the text. The last line still legible as recorded by Salt bore the syllable "Khaf," which was assumed to refer to Khafre, particularly because it was enclosed in a cartouche, the line enclosing hieroglyphs for a king or god. When discovered, however, the lines of text were incomplete, only referring to a “Khaf,” and not the full “Khafre.” The missing syllable “ra” was later added to complete the translation by Thomas Young, on the assumption that the text referred to “Khafre.” Young’s interpretation was based on an earlier facsimile in which the translation reads as follows:

… which we bring for him: oxen… and all the young vegetables; and we shall give praise to Wenofer … Khaf … the statue made for Atum-Hor-em-Akhet.[3]

Regardless of the translation, the stela offers no clear record of in what context the name Khafre was used in relation to the Sphinx – as the builder, restorer, or otherwise. The lines of text referring to Khafre flaked off and were destroyed when the Stela was re-excavated in the early 1900s.

In contrast, the “Inventory Stela” (believed to date from the twenty-sixth dynasty 664-525 B.C.E.) found by Auguste Mariette on the Giza plateau in 1857, describes how Khufu (the father of Khafre, the alleged builder) discovered the damaged monument buried in sand, and attempted to excavate and repair the dilapidated Sphinx. If accurate, this would date the Sphinx to a much earlier time. However, due to the late dynasty origin of the document, and the use of names for deities that belong to the Late Period, this text from the Inventory Stela is often dismissed by Egyptologists as late dynasty historical revisionism.[4]

Traditionally, the evidence for dating the Great Sphinx has been based primarily on fragmented summaries of early Christian writings gleaned from the work of the Hellenistic Period Egyptian priest Manethô, who compiled the now lost revisionist Egyptian history Aegyptika. These works, and to a lesser degree, earlier Egyptian sources, such as the “Turin Canon” and “Table of Abydos” among others, combine to form the main body of historical reference for Egyptologists, giving a consensus for a timeline of rulers known as the “King’s List,” found in the reference archive; the Cambridge Ancient History.[5][6] As a result, since Egyptologists have ascribed the Sphinx to Khafre, establishing the time he reigned would date the monument as well.

This position regards the context of the Sphinx as residing within part of the greater funerary complex credited to Khafre, which includes the Sphinx and Valley Temples, a causeway, and second pyramid.[7] Both temples display the same architectural style employing stones weighing up to 200 tons. This suggests that the temples, along with the Sphinx, were all part of the the same quarry and construction process.

In 2004, French Egyptologist Vassil Dobrev announced the results of a twenty-year reexamination of historical records, and uncovering of new evidence that suggests the Great Sphinx may have been the work of the little known Pharaoh Djedefre, Khafre’s half brother and a son of Khufu, the builder of the Great Pyramid of Giza. Dobrev suggests it was built by Djedefre in the image of his father Khufu, identifying him with the sun god Ra in order to restore respect for their dynasty.[8] He supports this by suggesting that Khafre’s causeway was built to conform to a pre-existing structure, which he concludes, given its location, could only have been the Sphinx.[4]

These later efforts notwithstanding, the limited evidence giving provenance to Khafre (or his brother) remains ambiguous and circumstantial. As a result, the determination of who built the Sphinx, and when, continues to be the subject of debate. As Selim Hassan stated in his report regarding his excavation of the Sphinx enclosure back in the 1940s:

Taking all things into consideration, it seems that we must give the credit of erecting this, the world’s most wonderful statue, to Khafre, but always with this reservation that there is not one single contemporary inscription which connects the Sphinx with Khafre, so sound as it may appear, we must treat the evidence as circumstantial, until such time as a lucky turn of the spade of the excavator will reveal to the world a definite reference to the erection of the Sphinx.[4]

Khufu ship

The Khufu ship is an intact full-size vessel from Ancient Egypt that was sealed into a pit in the Giza pyramid complex at the foot of the Great Pyramid of Giza around 2,500 B.C.E. The ship was almost certainly built for Khufu (King Cheops), the second pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom of Egypt.

It is one of the oldest, largest, and best-preserved vessels from antiquity. At 43.6 m overall, it is longer than the reconstructed Ancient Greek trireme Olympias and, for comparison, nine metres longer than the Golden Hind in which Francis Drake circumnavigated the world.

The ship was rediscovered in 1954 by Kamal el-Mallakh, undisturbed since it was sealed into a pit carved out of the Giza bedrock. It was built largely of cedar planking in the "shell-first" construction technique and has been reconstructed from more than 1,200 pieces which had been laid in a logical, disassembled order in the pit beside the pyramid.

The history and function of the ship are not precisely known. It is of the type known as a "solar barge," a ritual vessel to carry the resurrected king with the sun god Ra across the heavens. However, it bears some signs of having been used in water, and it is possible that the ship was either a funerary "barge" used to carry the king's embalmed body from Memphis to Giza, or even that Khufu himself used it as a "pilgrimage ship" to visit holy places and that it was then buried for him to use in the afterlife.

The Khufu ship has been on display to the public in a specially built museum at the Giza pyramid complex since 1982.

Alternative theories

In common with many famous constructions of remote antiquity, the Pyramids of Giza and the Great Sphinx have been the subject of numerous speculative theories and assertions by non-specialists, mystics, pseudohistorians, pseudoarchaeologists, and general writers. These alternative theories of the origin, purpose, and history of the monument typically invoke a wide array of sources and associations, such as neighboring cultures, astrology, lost continents and civilizations (such as Atlantis), numerology, mythology and other esoteric subjects.

One well-publicized debate was generated by the works of two writers, Graham Hancock and Robert Bauval, in a series of separate and collaborative publications from the late 1980s onwards.[9] Their claims include that the construction of the Great Sphinx and the monument at Tiwanaku near Lake Titicaca in modern Bolivia was begun in 10,500 B.C.E.; that the Sphinx's lion-shape is a definitive reference to the constellation of Leo; and that the layout and orientation of the Sphinx, the Giza pyramid complex and the Nile River is an accurate reflection or “map” of the constellations of Leo, Orion (specifically, Orion’s Belt) and the Milky Way, respectively.

Although universally regarded by mainstream archaeologists and Egyptologists as a form of pseudoscience,[10] Robert Bauval and Adrian Gilbert (1994) proposed that the three main pyramids at Giza form a pattern on the ground that is virtually identical to that of the three belt stars of the Orion constellation. Using computer software, they wound back the Earth's skies to ancient times, and witnessed a 'locking-in' of the mirror image between the pyramids and the stars at the same time as Orion reached a turning point at the bottom of its precessional shift up and down the meridian. This conjunction, they claimed, was exact, and it occurred precisely at the date 10,450 B.C.E.. And they claim that Orion is "West" of the Milky Way, in proportion to Giza and the Nile.[11]

Their theories, and the astronomical and archaeological data upon which they are based, have received refutations by some mainstream scholars who have examined them, notably the astronomers Ed Krupp and Anthony Fairall.[12]

Tourism

The Great Pyramid of Giza is one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, the only one still standing. Together with the other pyramids and the Great Sphinx, the site attracts thousands of tourists every year. Due largely to nineteenth-century images, the pyramids of Giza are generally thought of by foreigners as lying in a remote, desert location, even though they are located close to the highly populated city of Cairo.[13] Urban development reaches right up to the perimeter of the antiquities site. Egypt offers tourists more than antiquities, with nightlife, fine dining, snorkeling, and swimming in the Mediterranean Sea.

The ancient sites in the Memphis area, including those at Giza, together with those at Saqqara, Dahshur, Abu Ruwaysh, and Abusir, were collectively declared a World Heritage Site in 1979.[14]

Notes

- ↑ The Stele of Thotmes IV A Translation by D. Mallet. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- ↑ The Sphinx - Some Historywww.theglobaleducationproject.org. Retrieved July 30, 2007.

- ↑ Jason Colavito, Who Built the Sphinx?. Retrieved July 30, 2007.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Colin Reader, Giza Before the Fourth Dynasty Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum (JACF) 9 (2002): 5-21. Retrieved July 30, 2007.

- ↑ King Lists. www.phouka.com. Retrieved July 30, 2007.

- ↑ Index of Egyptian History Retrieved July 30, 2007.

- ↑ Ancient Egypt Research Associates (AERA) Khafre’s Monuments as a Unit Sphinx Project. Retrieved February 27, 2008.

- ↑ Nic Fleming, “I have solved riddle of the Sphinx, says Frenchman”, Dec. 14, 2004, The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved June 28, 2005.

- ↑ Atlantis Reborn Again BBC Horizon programme (2000) on alternate theories of Hancock and Bauval. Retrieved July 30, 2007.

- ↑ Mark Lehner, The Complete Pyramids – Solving the Ancient Mysteries (London: Thames & Hudson, 1997, ISBN 0500050848).

- ↑ Graham Hancock, and Santha Faiia. Heaven's Mirror. 1998.

- ↑ Tony Fairall Precession and the layout of the Ancient Egyptian pyramids (June 1999, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society) Retrieved July 30, 2007.

- ↑ Audrey DeLange and George DeLange, Giza Sphinx & Pyramids, The DeLange Home Page. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ↑ Memphis and its Necropolis – the Pyramid Fields from Giza to Dahshur UNESCO. Retrieved July 30, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hancock, Graham, and Santha Faiia. Heaven's Mirror: Quest for the Lost Civilization. Three Rivers Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0609804773

- Jenkins, Nancy. The Boat beneath the Pyramid: King Cheops' Royal Ship. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1980. ISBN 0030570611

- Lehner, Mark. The Complete Pyramids – Solving the Ancient Mysteries. London: Thames & Hudson, 1997. ISBN 0500050848

- Lipke, Paul. The Royal Ship of Cheops: A Retrospective Account of the Discovery, Restoration and Reconstruction. Based on interviews with Hag Ahmed Youssef Moustafa. Oxford: B.A.R., 1984. ISBN 0860542939

- Manley, Bill. The Seventy Great Mysteries of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500051232

- Reader, Colin. "Giza Before the Fourth Dynasty" Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum (JACF) 9 (2002): 5-21

- Reisner, George. A History of the Giza Necropolis, Volume 1. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1942. ISBN 0674402502

- Verner, Miroslav. The Pyramids – Their Archaeology and History. Atlantic Books, 2001. ISBN 1843541718

External links

All links retrieved December 6, 2022.

- Aerial view of Giza pyramids at Windows Live Local

- Explore Ancient Egypt NOVA.

- Sphinx photo gallery

- The Sphinx’s Nose

- Pyramid Construction: New Evidence Discovered at Giza by Zahi Hawass, director of the Giza Pyramids and Saqqara. Guardian’s Egypt.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Giza_pyramid_complex history

- Khafre's_Pyramid history

- Menkaure's_Pyramid history

- Great_Sphinx_of_Giza history

- Khufu_ship history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.