Atlantis

Atlantis (Greek: áźĎΝινĎá˝śĎ Î˝áżĎÎżĎ, "Island of Atlas") is a mythical island nation first mentioned and described by the classical Greek philosopher Plato in the dialogues Timaeus and Critias. Alleged to be an imperial power in the ancient world, the existence of Atlantis has been debated since Plato first spoke of it. The notion of Atlantis represents different ideas to everyone: for some, it is the ultimate archaeological site waiting to be discovered, a lost source of supernatural knowledge and power, or perhaps it is nothing more than a philosophical treatise on the dangers of a civilization at the pinnacle of its power. Whether Atlantis did exist or is merely the creation of Plato may never be known. Nonetheless, the very idea of its existence continues to inspire and intrigue many, echoing our desire to achieve or return to an age of prosperity.

Origin

Plato's account of Atlantis, believed to be the first, is found in the dialogues Timaeus and Critias, written in the year 360 B.C.E. In the Socratic dialogue style, Plato conveys his story through a conversation among politicians Critias and Hermocrates as well as the philosophers Socrates and Timaeus. It is Critias who speaks of Atlantis, first in the Timaeus, describing briefly the vast empire "beyond the pillars of Hercules" that was defeated by Athenians after it attempted to conquer Europe and Asia Minor. In Timaeus Critias goes into more detail as he describes the civilization of Atlantis. Critias claims that his accounts of ancient Athens and Atlantis stem from a visit to Egypt by the Athenian lawgiver Solon in the sixth century B.C.E. In Egypt, Solon met a priest of Sais, who translated the history of ancient Athens and Atlantis, recorded on papyri in Egyptian hieroglyphs, into Greek.

According to Critias, the Hellenic gods of old divided the land so that each god owned a share. Poseidon was appropriately, and to his liking, bequeathed the island of Atlantis. The island was larger than Libya and Asia Minor combined, but it later sank due to an earthquake and became an impassable mud shoal, inhibiting travel to any part of the ocean.

The Egyptians described Atlantis as an island approximately 700 kilometers (435 miles) across, comprising mostly mountains in the northern portions and along the shore, and encompassing a great plain of an oblong shape in the south. Fifty stadia (about 600 kilometers; 375 miles) inland from the coast was a mountain, where a native woman lived, with whom Poseidon fell in love and who bore him five pairs of male twins. The eldest of these, Atlas, was made rightful king of the entire island and the ocean (called the Atlantic Ocean in honor of Atlas), and was given the mountain of his birth and the surrounding area as his fiefdom. Atlas's twin Gadeirus or Eumelus in Greek, was given the extremity of the island towards the Pillars of Heracles. The other four pairs of twinsâAmpheres and Evaemon, Mneseus and Autochthon, Elasippus and Mestor, and Azaes and Diaprepesâwere likewise given positions of power on the island.

Poseidon carved the inland mountain where his love dwelt into a palace and enclosed it with three circular moats of increasing width, varying from one to three stadia and separated by rings of land proportional in size. The Atlanteans then built bridges northward from the mountain, making a route to the rest of the island. They dug a great canal to the sea, and alongside the bridges carved tunnels into the rings of rock so that ships could pass into the city around the mountain; they carved docks from the rock walls of the moats. Every passage to the city was guarded by gates and towers, and a wall surrounded each of the city's rings.

The society of Atlantis lived peacefully at first, but as the society advanced, the desires of the islanders forced them to reach beyond the island's boundaries. According to Critias, nine thousand years before his lifetime, a war took place between those outside the "Pillars of Hercules" (generally thought to be the Strait of Gibraltar) and those who dwelt within them. The Atlanteans had conquered the parts of Libya within the pillars of Heracles as far as Egypt and the European continent as far as Tyrrhenia, and subjected its people to slavery. The Athenians led an alliance of resistors against the Atlanteansâ empire, but the alliance disintegrated, leaving Athens alone to prevail alone against the empire, liberating the occupied lands. After the Atlanteans were forced back to their own island, a tremendous earthquake destroyed the civilization and the island sank into the ocean, thus ending the once mighty society.

Fact or Fiction

Many ancient philosophers viewed Atlantis as fiction, including (according to Strabo), Aristotle. However, in antiquity there were also philosophers, geographers, and historians who took Plato's story as truth. One such was the philosopher Crantor, a student of Plato's student Xenocrates, who tried to find proof of the existence of Atlantis. His work, a commentary on Plato's Timaeus, is lost, but another ancient historian, Proclus, reports that Crantor traveled to Egypt and actually found columns with the history of Atlantis written in Egyptian hieroglyphic characters.[1] As with all works of antiquity, it is difficult to evaluate ambiguous proclamations since no hard proof other than writings survives.

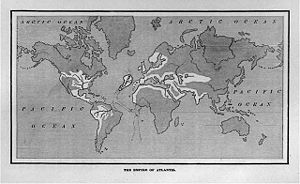

The debate over Atlantis remained relatively quiet until the late nineteenth century. With Heinrich Schliemann's 1872 discovery of the lost city of Troy using Homer's Iliad and Odyssey as guides, it became clear that classical sources once regulated to mythology may actually contain some lost truths. The scholar Ignatius Donnelly published Atlantis: the Antediluvian World in 1882, helping to stimulate popular interest in Atlantis. Donnelly took Plato's account of Atlantis seriously and attempted to establish that all known ancient civilizations were descended from its high Neolithic culture. Others proposed more outlandish ideas attributing supernatural aspects to Atlantis and combining it with stories of other lost continents such as Mu and Lemuria by popular figures in the Theosophy movement, occult, and the growing New Age phenomenon.[2]

Most scholars dismiss belief in Atlantis as a New Age idea, and regard the most plausible explanation as that Atlantis was a parable of Plato's, or was based on a known civilization, such as the Minoans. The fact that Plato often told didactic stories disguised as fictitious tales is cited in support of this view. The Cave is perhaps the most famous example, in which Plato illustrates the nature of reality by telling a story. Such scholars warn that to take Plato's story literally is to misinterpret him. It is more likely that Plato was sending a warning to his fellow Greeks about the dangers of imperial expansion, political ambition, as well as promoting nobility and the acquisition of knowledge not for personal gain.[3]

The truth of Platoâs intentions remains known only to Plato, but no one can doubt the symbolic longevity of his story. Atlantis may not be a physical place, but it certainly has been established as a location in humanity's shared imagination.

Location hypotheses

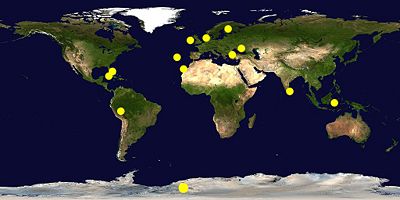

There have been dozensâperhaps hundredsâof locations proposed for Atlantis, to the point where the name has become a generic term rather than referring to one specific (possibly even genuine) location. This is reflected in the fact that many proposed sites are not within the Atlantic Ocean at all. Some are scholarly or archaeological hypotheses, while others have been made by psychic or pseudoscientific means. Many of the proposed sites share some of the characteristics of the Atlantis story (water, catastrophic end, relevant time period), but none has been proven conclusively to be a true historical Atlantis. Below is a list of the more popular (and plausible) locations that have been suggested.

Inside the Mediterranean

Most of the historically proposed locations are in or near the Mediterranean Sea, either islands such as Sardinia, Crete, Santorini, Cyprus, or Malta.

The volcanic eruption on Thera, dated either to the seventeenth or the fifteenth century B.C.E., caused a massive tsunami that experts hypothesize devastated the Minoan civilization on the nearby island of Crete, further leading some to believe that this may have been the catastrophe that inspired the story. Supporters of this idea cite that the fact that the Egyptians used a lunar calendar based on months, and the Greeks a solar one based on years. It is therefore possible that the measure of time interpreted as nine thousand years may actually have been nine thousand months, placing the destruction of Atlantis within approximately seven hundred years, there being 13 lunar months in a solar year.[4]

The volcanic eruptions on the Mediterranean island of Santorini during Minoan times were likely powerful enough to cause the cataclysm that befell Atlantis. The main criticism of this hypothesis is that the ancient Greeks were well aware of volcanoes, and if there was a volcanic eruption it seems likely that they would have mentioned it. Additionally, Pharaoh Amenhotep III commanded an emissary to visit the cities surrounding Crete and found the towns occupied shortly after the time Santorini was speculated to have completely destroyed the area.

Another hypothesis is based on a re-creation of the geography of the Mediterranean Sea at the time of Atlantis' supposed existence. Plato states that Atlantis was located beyond the "Pillars of Hercules," the name given to the Strait of Gibraltar linking the Mediterranean to the Atlantic Ocean. Eleven thousand years ago, the sea level in the area was some 130 meters lower, exposing a number of islands in the strait. One of these, Spartel, could have been Atlantis, though there are a number of inconsistencies with Plato's account.

In 2002 Italian journalist Sergio Frau published a book, Le colonne d'Ercole ("Pillars of Hercules"), in which he stated that before Eratosthenes all the ancient Greek writers located the Pillars of Hercules on the Strait of Sicily, while only Alexander the Great's conquest of the east obliged Eratosthenes to move the pillars to Gibraltar in his description of the world.[5] According to his thesis, the Atlantis described by Plato could be identified with Sardinia. In fact, a tsunami caused catastrophic damage to Sardinia, destroying the enigmatic Nuragic civilization. The few survivors migrated to the nearby Italian peninsula, founding the Etruscan civilization, the basis for the later Roman civilization, while other survivors were part of those Sea Peoples that attacked Egypt.

Outside the Mediterranean

Beyond the Mediterranean Sea, locations all over the world have been cited as the location for Atlantis. From Ireland, Sweden, to Indonesia and Japan, many of these theories rely on little hard evidence. Two of the most talked about areas, however, are the Caribbean and Antarctica.

Often connected to the mysterious events alleged to have transpired in the Bermuda Triangle, the Caribbean has received attention for underwater structures, often called "The Bimini Road." Discovered by pilots in the 1960s, the Bimini Road consists of large rocks that are laid in two parallel formations in shallow water, running a couple miles away from the Bimini Islands.[6] Numerous expeditions have set out for the Bimini Islands to attempt to prove or disprove that the formation is man-made and somehow connected to Atlantis. Most scientists, particularly geologists, find the evidence inconclusive or have concluded that the phenomenon is a natural occurrence. Believers, however, strongly argue that the rock formation is too symmetrical and deliberate to be an act of nature. In either case, no other remains have been found that suggest the Bimini Road leads to Atlantis.

The theory that Antarctica was at one point Atlantis was particularly fashionable during the 1960s and 1970s, spurred on by the isolation of the continent, H. P. Lovecraft's novella At the Mountains of Madness, and also the Piri Reis map, which purportedly shows Antarctica as it would be ice free, suggesting human knowledge of that period. Charles Berlitz, Erich Von Daniken, and Peter Kolosimo have been amongst those popular authors who made this proposal. However, the theory of continental drift contradicts this idea, because Antarctica was in its current location in Plato's lifetime and has retained its inhospitable climate. Still, the romance of Antartica's relatively unexplored regions continues to lead many to superimpose ideas, such as Atlantis, onto it.

Pop Culture

Exploration and discovery of long lost cities and civilizations is a theme that is not bound by space or time in the popular imagination. Atlantis has become the ultimate mythical city, its name becoming iconic for all other lost cities. Atlantis appears in all types of literature, from Renaissance works to modern day science fiction/fantasy, archaeological and scientific works, to New Age books. Television andmovies have also capitalized on the allure of Atlantis. The myth is so alluring that one of the largest hotel in the Bahamas is the Atlantis Paradise Island Resort, a lost city themed resort.

Within the New Age movement there are those that believe Atlanteans were technologically advanced, that they self-destructed due to their rapid advancement, or that they used (and perhaps were themselves) extraterrestrial technology. Similar ideas have been attributed to many other ancient societies, such as the Egyptians, as many new age beliefs intend to unify different mysteries under one idea. In the end, Atlantis' continued discussion and study is a testament to humankind's endless curiosity and desire not to leave our current charting of the world where it is, but to continue to look for mysteries to explore, and lost worlds from our past to discover.

Footnotes

- â H. G. Nesselrath, "Where the Lord of the Sea Grants Passage to Sailors through the Deep-blue Mere no More: The Greeks and the Western Seas," Greece & Rome 52 (2005): 153-171.

- â Robert Todd Carroll, (2005) "Atlantis" Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- â Julia Annas, Plato: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003).

- â Alex Hawk (1998), "Atlantis.....Thira?".

- â Sergio Frau, Le colonne d'Ercole (Rome: Nur Neon, 2002, ISBN 8890074000).

- â Ellie Crystal (2007), "Bimini Road." Retrieved June 15, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Ancient sources

- Plato. 360 B.C.E. Timaeus, translated by Benjamin Jowett. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- Plato. 360 B.C.E. Critias, translated by Benjamin Jowett. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

Modern sources

- Bichler, R. (1986). âAthens besiegt Atlantis. Eine Studie Ăźber den Ursprung der Staatsutopie.â Canopus 20 (51): 71-88.

- De Camp, L. S. (1954). Lost Continents: The Atlantis Theme in History, Science, and Literature. New York: Gnome Press.

- Donnelly, I. (1882). Atlantis: The Antediluvian World. New York: Harper & Bros. Available online from Project Gutenberg. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- Ellis, R. (1998). Imaging Atlantis. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0679446028

- Erlingsson, U. (2004). Atlantis from a Geographer's Perspective: Mapping the Fairy Land. Miami, FL: Lindorm. ISBN 0975594605

- Flem-Ath, R. & Wilson, C. (2000). The Atlantis Blueprint. London: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0316853135

- Frau, S. (2002). Le Colonne d'Ercole: Un'inchiesta. Rome: Nur Neon. ISBN 8890074000

- Gill, C. (1976). âThe origin of the Atlantis myth.â Trivium 11: 8-9.

- GĂśrgemanns, H. (2000). âWahrheit und Fiktion in Platons Atlantis-Erzählung.â Hermes 128: 405-420.

- Griffiths, J. P. (1985). âAtlantis and Egypt.â Historia 34: 35 ff.

- Heidel, W. A. (1933). âA suggestion concerning Platon's Atlantis.â Daedalus 68: 189-228.

- Jordan, P. (1994). The Atlantis Syndrome. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0750935189

- Martin, T. H. [1841] (1981). âDissertation sur l'Atlantide,â in T. H. Martin, Ătudes sur le TimĂŠe de Platon. Paris: Librairie philosophique J. Vrin. pp. 257-332.

- Morgan, K. A. (1998). "Designer history: Plato's Atlantis story and fourth-century ideology." Journal of Hellenic Studies 118: 101-118.

- Nesselrath, H. G. (1998). "Theopomps Meropis und Platon: Nachahmung und Parodie." GĂśttinger Forum fĂźr Altertumswissenschaft 1: 1-8.

- Nesselrath, H. G. (2001a). "Atlantes und Atlantioi: Von Platon zu Dionysios Skytobrachion." Philologus 145: 34-38.

- Nesselrath, H. G. (2001b). "Atlantis auf ägyptischen Stelen? Der Philosoph Krantor als Epigraphiker." Zeitschrift fßr Papyrologie und Epigraphik 135: 33-35.

- Nesselrath, H. G. (2002). Platon und die Erfindung von Atlantis, MĂźnchen/Leipzig: KG Saur Verlag. ISBN 3-598-77560-1

- Nesselrath, H. G. (2005). "Where the Lord of the Sea Grants Passage to Sailors through the Deep-blue Mere no More: The Greeks and the Western Seas." Greece & Rome 52: 153-171.

- Phillips, E. D. (1968). "Historical Elements in the Myth of Atlantis." Euphrosyne 2: 3-38.

- Ramage, E. S. (1978). Atlantis: Fact or Fiction?. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253104823

- Settegast, M. (1987). Plato Prehistorian: 10,000 to 5000 B.C.E. in Myth and Archaeology. Cambridge, MA: Rotenberg Press.

- Spence, L. [1926] (2003). The History of Atlantis. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0486427102

- SzlezĂĄk, T. A. (1993). "Atlantis und Troia, Platon und Homer: Bemerkungen zum Wahrheitsanspruch des Atlantis-Mythos." Studia Troica 3: 233-237.

- Vidal-Naquet, P. (1986). "Athens and Atlantis: Structure and Meaning of a Platonic Myth," in P. Vidal-Naquet, The Black Hunter. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 263-284. ISBN 0801832519

- Wilson, C. (1997). From Atlantis to the Sphinx. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 0880641762

- Zangger, E. (1993). The Flood from Heaven: Deciphering the Atlantis Legend. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0688113508

Further reading

- Andrews, Shirley. Atlantis. Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 156718023X

- Ashe, Geoffrey. 1992. Atlantis: Lost Lands, Ancient Wisdom. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0500810397

- Dunbavin, Paul. Atlantis of the West: The Case for Britain's Drowned Megalithic Civilization. ISBN 0786711450

- Erlingsson, Ulf. 2004. Atlantis from a Geographer's Perspective: Mapping the Fairy Land. Lindorm Publishing. ISBN 0975594605 Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- Joseph, Frank. 2002. The Destruction of Atlantis: Compelling Evidence of the Sudden Fall of the Legendary Civilization. Bear & Company. ISBN 1879181851

- Matlock, Gene. 2002. The Last Atlantis Book Youâll Ever Have to Read: The Atlantis-Mexico-India Connection. Tempe, AZ: Dandelion Books. ISBN 978-1893302204

- Mifsud, Anton, Simon Mifsud, Chris Agius Sultana, and Charles Savona Ventura. 2001. Echoes of Plato's Island. 2nd edition. Malta. ISBN 9993215015

- Zangger, Eberhard. 1992. The Flood from Heaven: Deciphering the Atlantis Legend. Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0688113508

External links

All links retrieved August 21, 2023.

- Atlantis: Myth or Memory? from UnXplained-Factor.

- Atlantis: the Myth from Encyclopedia Mythica.

- BBC News. 2001. "Atlantis 'obviously near Gibraltar.'"

- BBC News. 2004. "Have scientists really found the lost city of Atlantis?"

- BBC News. 2004. "Satellite images 'show Atlantis' in Spain."

- BBC News. 2005. "Tsunami clue to 'Atlantis' found."

- Atlantis The Skeptics Dictionary.

Africa-Eurasia |

Americas |

Eurasia |

Oceania | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Africa |

Antarctica |

Asia |

Australia |

Europe |

N. America |

S. America | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Geological supercontinents Gondwana ⢠Laurasia ⢠Pangaea ⢠Pannotia ⢠Rodinia ⢠Columbia ⢠Kenorland ⢠Ur ⢠Vaalbara | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mythical and theorized continents Atlantis ⢠Kerguelen Plateau ⢠Lemuria ⢠Mu ⢠Terra Australis ⢠Zealandia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.