Lake Titicaca

| Lake Titicaca | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | |

| Lake type | Mountain Lake |

| Primary sources | 27 rivers |

| Primary outflows | Desaguadero River Evaporation |

| Catchment area | 58,000 km² |

| Basin countries | Peru Bolivia |

| Max length | 190 km |

| Max width | 80 km |

| Surface area | 8,372 km² |

| Average depth | 107m |

| Max depth | 281m |

| Water volume | 893 km³ |

| Shore length1 | 1,125 km |

| Surface elevation | 3,812 m |

| Islands | 42+ islands See Article |

| Settlements | Puno, Peru Copacabana, Bolivia |

| 1 Shore length is an imprecise measure which may not be standardized for this article. | |

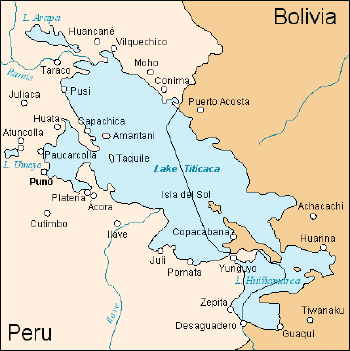

Lake Titicaca is the highest commercially navigable lake in the world, at 12,507 feet (3,812 m) above sea level, and the largest freshwater lake in South America. Located in the Altiplano (high plains) in the Andes on the border of Peru and Bolivia, the western part of the lake belongs to the Puno Region of Peru, and the eastern side is located in the Bolivian La Paz Department. The Bolivian naval force uses the lake to carry out exercises, maintaining an active navy despite being landlocked.

The lake is composed of two nearly separate sub-basins that are connected by the Strait of Tiquina, which is 800 m across at the narrowest point. The larger sub-basin, Lago Grande (also called Lago Chucuito) has a mean depth of 135m and a maximum depth of 284m. The smaller sub-basin, Lago Huiñaimarca (also called Lago Pequeño) has a mean depth of 9m and a maximum depth of 40m.

The partly salt Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela is the only body of water in South America bigger than Titicaca, at about 13,000 square kilometers, but some say it should be classified as a sea because it is connected to the ocean.

The origin of the name Titicaca is unknown. It has been translated as "Rock Puma," allegedly because of its resemblance to the shape of a puma hunting a rabbit, combining words from the local languages Quechua and Aymara. It has also been translated as "Crag of Lead."

In 1862 the first steamer to ply the lake was prefabricated in England and carried in pieces on muleback up to the lake. Today vessels make regular crossings from Puno, on the Peruvian shore, to the small Bolivian port of Guaqui, where a railroad connects it with La Paz, capital of Bolivia. The world's second-highest railroad runs from Puno down to the Pacific, creating an important link with the sea for landlocked Bolivia.

Geography

More than 25 rivers empty into Titicaca, and the lake has 41 islands, some of which are densely populated.

Titicaca is fed by rainfall and meltwater from glaciers on the sierras that abut the Altiplano. One small river, the Desaguadero, drains the lake at its southern end and flows south through Bolivia to Lake Poopó. This single outlet empties only five percent of the lake's excess water; the rest is lost by evaporation under the fierce sun and strong winds of the dry Altiplano.

Titicaca's level fluctuates seasonally and over a cycle of years. During the rainy season (December to March) the level of the lake rises, receding during the dry winter months. It was formerly believed that Titicaca was slowly drying up, but modern studies have seemed to refute this, indicating a more or less regular cycle of rise and fall.

Titicaca's waters are limpid and only slightly brackish, with salinity ranging from 5.2 to 5.5 parts per 1,000. Surface temperatures average 56º F (14º C); from a thermocline at 66 feet (20 m) temperatures drop to 52º F (11º C) at the bottom. Analyses show measurable quantities of sodium chloride, sodium sulfate, calcium sulfate, and magnesium sulfate in the water.

Lake Titicaca's fish consist principally of two species of killifish (Orestias) – a small fish, usually striped or barred with black, and a catfish (Trichomycterus). In 1939 and subsequently, trout were introduced into Titicaca. A large frog (Telmatobius), which may reach a length of nearly a foot, inhabits the shallower regions of the lake.

The Altiplano (Spanish for high plain), where the Andes are at their widest, is the most extensive area of high plateau on earth outside of Tibet. At the end of the Pleistocene epoch, the whole extent of the Altiplano was covered by a vast lake, Ballivián, the present remnants of which are Lakes Titicaca and Poopó, the latter a saline lake extending south of Oruro, Bolivia. Salar de Uyuni and Salar de Coipasa are two large dry salt flats also formed after the Altiplano paleolakes dried out.

The climate of the Altiplano is cool and semi-arid to arid, with mean annual temperatures that vary from 3 degrees C near the western mountain range to 12 degrees C near Lake Titicaca. Total annual rainfall is more than 800 mm near and over Lake Titicaca.

Islands

Uros

Titicaca is notable for a population of people who live on the Uros, a group of about 43 artificial islands made of floating reeds. Their original purpose was defensive, and they could be moved if a threat arose. One of the islands retains a watchtower largely constructed of reeds. These islands have become a major tourist attraction, drawing excursions from the lakeside city of Puno.

Uros is also the name of the pre-Incan people who lived on the islands. Around 3,000 descendants of the Uros are alive today, although only a few hundred still live on and maintain the islands; most have moved to the mainland.

The Uros traded with the Aymara tribe on the mainland, interbreeding with them and eventually abandoning the Uro language for that of the Aymara. About 500 years ago they lost their original language. When this pre-Incan civilization was conquered by the Incas, they were forced to pay taxes to them, and often were made slaves.

The islets are made of totora reeds, which grow in the lake. The dense roots that the plants develop support the islands. They are anchored with ropes attached to sticks driven into the bottom of the lake. The reeds at the bottoms of the islands rot away fairly quickly, so new reeds are added to the top constantly. This is especially important in the rainy season when the reeds decompose much faster. The islands last about 30 years. Much of the Uros' diet and medicine also revolve around these reeds. When a reed is pulled, the white bottom is often eaten for iodine, which prevents goiter. Just as the Andean people rely on the coca leaf for relief from a harsh climate and hunger, the Uros people rely on the totora reeds. They wrap the reed around a place where they feel pain and also make a reed flower tea.

Larger islands house about ten families, while smaller ones, only about 30 meters wide, house only two or three. There are about two or three children per family. Early schooling is done on several islands, including a traditional school and a school run by a Christian church. Older children and university students attend school on the mainland, often in nearby Puno.

The residents fish in the lake. They also hunt birds such as gulls, ducks, and flamingos and graze their cattle on the islets. They run craft stalls aimed at the numerous tourists who land on ten of the islands each year. They barter totora reeds on the mainland in Puno to get products they need like quinoa or other foods. Food is cooked with fires placed on piles of stones. The Uros do not reject modern technology: some boats have motors, some houses have solar panels to run appliances such as televisions, and the main island is home to an Uros-run FM radio station, which plays music for several hours a day.

Amantaní

Amantaní is another small island in Lake Titicaca, this one populated by Quechua speakers. About eight hundred families live in six villages on the basically circular 15-square-kilometer island. There are two mountain peaks, called Pachatata (Father Earth) and Pachamama (Mother Earth), and ancient ruins on the top of both peaks. The hillsides that rise up from the lake are terraced and planted with wheat, potatoes, and vegetables. Most of the small fields are worked by hand. Long stone fences divide the fields, and cattle, sheep, and alpacas graze on the hillsides.

There are no cars on the island, and no hotels. A few small stores sell basic goods, and there is a health clinic and school. Electricity is produced by a generator and limited to a couple of hours each day.

Some of the families on Amantaní open their homes to tourists for overnight stays and provide cooked meals. Guests typically bring food staples (cooking oil, rice, sugar) as a gift or school supplies for the children. The islanders hold nightly traditional dance shows for the tourists and offer to dress them up in their traditional clothes so they can participate.

Taquile

Taquile is a hilly island located 45 kilometers (28 mi) east of Puno. It is narrow and long and was used as a prison during the Spanish Colony and into the 20th century. In 1970, it became property of the Taquile people, who have inhabited the island since then. The island is 5.5 by 1.6 km (3.42 by 0.99 mi) in size (maximum measurements), with an area of 5.72 square kilometers (2.21 sq mi). The highest point of the island is 4,050 meters (13,300 ft) above sea level, and the main village is at 3,950 meters (13,000 ft). Pre-Inca ruins are found on the highest part of the island, and agricultural terraces on hillsides. From the hillsides of Taquile, one has a view of the tops of Bolivian mountains. The inhabitants, known as Taquileños, are southern Quechua speakers.

Taquile is especially known for its handicraft tradition, which is regarded as being of the highest quality. "Taquile and Its Textile Art" were honored by being proclaimed "Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity" by UNESCO. Knitting is exclusively performed by males, starting at age eight. The women exclusively make yarn and weave.

Taquileans are also known for having created an innovative, community-controlled tourism model, offering home stays, transportation, and restaurants to tourists. Ever since tourism started coming to Taquile in the 1970s, the Taquileños have slowly lost control over the mass day-tourism operated by non-Taquileans. They have thus developed alternative tourism models, including lodging for groups, cultural activities, and local guides who have completed a 2-year training program. The local Travel Agency, Munay Taquile, has been established to regain control over tourism.

The people in Taquile run their society based on community collectivism and on the Inca moral code ama sua, ama llulla, ama qhilla, (do not steal, do not lie, do not be lazy). The island is divided into six sectors or suyus for crop rotation purposes. The economy is based on fishing, terraced farming based on potato cultivation, and tourist-generated income from the roughly 40,000 tourists who visit each year.

Isla del Sol

Situated on the Bolivian side of the lake with regular boat links to the Bolivian town of Copacabana, Isla del Sol ("Island of the Sun") is one of the lake's largest islands. In Inca mythology it figured as the place of their origin, and several important Inca ruins exist on the island. Its economy is mainly driven by tourism revenues, but subsistence farming and fishing are widely practiced.

Excavations at the archaeological site of Ch'uxuqulla, located on a small peak, led to the recovery of Archaic Preceramic remains that radiocarbon dated to about 2200 B.C.E.[1] Eight obsidian flakes were recovered, and analysis of three flakes revealed they were from the Colca Canyon, providing clear evidence that inhabitants of the island were participating in a wider network of exchange.

An underwater archaeological research project was undertaken off the Island of the Sun during 1989-1992. The ruins of an ancient temple, a terrace for crops, a long road, and an 800-meter (2,600 feet) long wall were discovered. The pre-Incan ruins have been attributed to the indigenous Tiwanaku or Tiahuanaco people. [2]

Stories of lost treasure were enough to draw the famous French oceanographer Jacques Cousteau to explore the lake, but he discovered only ancient pottery.[3]

Isla de la Luna

Isla de la Luna is situated east from the bigger Isla del Sol. Both islands belong to the La Paz Department of Bolivia. According to legends that refer to Inca mythology Isla de la Luna (Spanish for "island of the moon") is where Viracocha commanded the rising of the moon. Ruins of a supposed Inca nunnery (Mamakuna) occupy the oriental shore.[4]

Archaeological excavations[5] indicate that the Tiwanaku peoples (around 650–1000 C.E.) built a major temple on the Island of the Moon. Pottery vessels of local dignitaries dating from this period have been excavated on islands in Lake Titicaca. The structures seen on the island today were built by the Inca (circa 1450–1532) directly over the earlier Tiwanaku ones.

Suriki

Suriki lies in the Bolivian part of lake Titicaca (in the southeastern part also known as lake Wiñaymarka).[6]

Suriki is thought to be the last place where the art of reed boat construction survives, at least as late as 1998. Craftsmen from Suriqui helped Thor Heyerdahl in the construction of several of his projects, such as the reed boats Ra II and Tigris, and a balloon gondola.[6]

History

The lake has had a number of steamships, each of which was built in the United Kingdom in "knock down" form with bolts and nuts, disassembled into many hundreds of pieces, transported to the lake, and then riveted together and launched.

In 1862 Thames Ironworks on the River Thames built the iron-hulled sister ships SS Yavari and SS Yapura under contract to the James Watt Foundry of Birmingham. The ships were designed as combined cargo, passenger, and gunboats for the Peruvian Navy. After several years' delay in delivery from the Pacific coast to the lake, Yavari was launched in 1870 and Yapura in 1873. Yavari was 100 feet (30 m) long, but in 1914 her hull was lengthened for extra cargo capacity and she was re-engined as a motor vessel.[7]

In November 1883, during the final phase of the War of the Pacific, the Chilean military command sent the Chilean torpedo boat Colo Colo to the lake, via railroad, from Mollendo to Puno to control the area.[8]

In 1892, William Denny and Brothers at Dumbarton on the River Clyde in Scotland built SS Coya. She was 170 feet (52 m) long and was launched on the lake on March 4, 1893.[9]

In 1905, Earle's Shipbuilding at Kingston upon Hull on the Humber built SS Inca.[10] By then, a railway served the lake, so the ship was delivered in kit form by rail. At 220 feet (67 m) long and 1,809 tons (1,994 U.S. tons), Inca was the lake's largest ship thus far. In the 1920s, Earle's supplied a new bottom for the ship, which also was delivered in kit form.[10]

Trade continued to grow, so in 1930, Earle's built SS Ollanta.[10] Her parts were landed at the Pacific Ocean port of Mollendo and brought by rail to the lake port of Puno. At 260 feet (79 m) long and 2,200 tons (425 U.S. tons), she was considerably larger than the Inca, so first a new slipway had to be built to build her. She was launched in November 1931.[10]

In 1975, Yavari and Yapura were returned to the Peruvian Navy, which converted Yapura into a hospital ship and renamed her BAP Puno.[7] The Navy discarded Yavari, but in 1987, charitable interests bought her and started restoring her. She is now moored at Puno Bay and provides static tourist accommodation while her restoration continues.[7] Coya was beached in 1984, but restored as a floating restaurant in 2001. Inca survived until 1994, when she was broken up. Ollanta is no longer in scheduled service, but PeruRail has been leasing her for tourist charter operations.[11]

Notes

- ↑ Charles Stanish, Richard L. Burger, Lisa M. Cipolla, Michael D. Glascock, and Esteban Quelima, "Evidence for Early Long-Distance Obsidian Exchange and Watercraft Use from the Southern Lake Titicaca Basin of Bolivia and Peru" Latin American Antiquity 13(4) (2002): 444-454.

- ↑ Johan Reinhard, "Underwater Archaeological Research in Lake Titicaca, Bolivia" in Ancient America: Contributions to New World Archaeology, Nicholas J. Saunders (ed.) (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 1992, ISBN 978-0946897483), 117-143.

- ↑ Ancient temple found under Lake Titicaca BBC News (August 23, 2000). Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ Isabel Albiston, Michael Grosberg, and Mark Johanson, Bolivia (Lonely Planet, 2019, ISBN 978-1786574732).

- ↑ Brian S. Bauer and Charles Stanish, Ritual and Pilgrimage in the Ancient Andes (University of Texas Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0292708907).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ben Box, South American Handbook (Footprint Books, 2018, ISBN 978-1911082231).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 The History of the Ship YAVARI 1862. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ William F. Sater, Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879–1884 (University of Nebraska Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0803227996)

- ↑ Paul Strathdee, Launched 1893: ss COYA Shipping Times. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Michael Grace, The SS Ollanta Cruising the Past, November 16, 2009. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ Dale Brown, Steam in Peru 2001 International Steam Pages. Retrieved June 22, 2024

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Albiston, Isabel, Michael Grosberg, and Mark Johanson. Bolivia. Lonely Planet, 2019. ISBN 978-1786574732

- Bauer, Brian S., and Charles Stanish. Ritual and Pilgrimage in the Ancient Andes. University of Texas Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0292708907

- Box, Ben. South American Handbook. Footprint Books, 2018. ISBN 978-1911082231

- Rachowiecki, Rob, and Charlotte Beech. Peru. Lonely Planet series, 2004. ISBN 1740592093

- Sater, William F. Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879–1884. University of Nebraska Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0803227996

- Saunders, Nicholas J. (ed.). Ancient America: Contributions to New World Archaeology. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 1992. ISBN 978-0946897483

- Stanish, Charles. Lake Titicaca: Legend, Myth and Science. The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1931745826

External links

All links retrieved March 7, 2025.

- Lake Titicaca Tentative Lists UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- Lake Titicaca Crystalinks.

- Lake Titicaca: Peru’s Natural Heritage Peru Travel

- Lake Titicaca Lonely Planet

- Lake Titicaca – Bolivia and Peru Global Nature Fund

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.