Difference between revisions of "Phenomenology" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (41 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}} | |

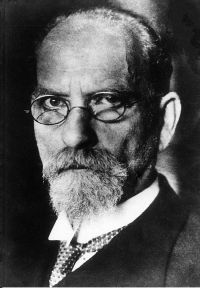

| − | {{ | + | [[File:Edmund Husserl 1910s.jpg|thumb|200px|[[Edmund Husserl]]]] |

| − | {{ | ||

| − | '''Phenomenology''' is | + | '''Phenomenology''' is, in its founder [[Edmund Husserl]]'s formulation, the study of experience and the ways in which things present themselves in and through experience. Taking its starting point from the first-person perspective, phenomenology attempts to describe the essential features or structures of a given experience or any experience in general. One of the central structures of any experience is its [[intentionality]], or its ''being directed toward'' some object or state of affairs. The theory of intentionality, the central theme of phenomenology, maintains that all experience necessarily has this object-relatedness and thus one of the catch phrases of phenomenology is “all [[consciousness]] is consciousness ''of''.” In short, in our experiences we are always already related to the world and to overlook this fact is to commit one of the cardinal sins of phenomenology: abstraction. |

| − | + | This emphasis on the intentional structure of experience makes phenomenology distinctive from other modern [[epistemology|epistemological]] approaches that have a strong separation between the experiencing subject and the object experienced. Starting with [[Rene Descartes]], this subject/object distinction produced the traditions of [[rationalism]] and [[empiricism]] which focus on one of these aspects of experience at the expense of the other. Phenomenology seeks to offer a corrective to these traditions by providing an account of how the experiencing subject and object experienced are not externally related, but internally unified. This unified relation between the subject and object is the “''phenomena''” that phenomenology takes as the starting point of its descriptive analysis. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| + | The discipline of phenomenology as a historical movement originates with [[Edmund Husserl]] (1859-1938). He is considered the “father” of phenomenology and worked copiously to establish it as a rigorous science. It continued to develop in twentieth-century European philosophy through the works of [[Max Scheler]], [[Martin Heidegger]], [[Hannah Arendt]], [[Jean-Paul Sartre]], [[Maurice Merleau-Ponty]], [[Paul Ricoeur]], [[Emmanuel Levinas]], [[Jacques Derrida]], and [[Jean-Luc Marion]]. Given its continual development and appropriation in various other disciplines (most notably - [[ontology]], [[sociology]], [[psychology]], [[ecology]], [[ethics]], [[theology]], [[philosophy of mind]]) it is considered to be one of the most significant philosophical movements in the twentieth century. | ||

| − | + | == Husserl - The Father of Phenomenology == | |

| − | + | {{main|Edmund Husserl}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Edmund Husserl was born on April 8, 1859, into a [[Jewish]] family living in the Austrian Empire. He began his academic career as a mathematician, defending his doctoral dissertation in [[Vienna]] in 1882. While in Vienna, he attended lectures by the prominent psychologist and philosopher [[Franz Brentano]], who was exercise a considerable influence on Husserl in the years to come. | |

| − | + | In 1886 Husserl converted to [[Protestantism]] and the following year he defended his ''Habilitation'' on the concept of number at the university in Halle, where he was to spend the next fourteen years as ''Privatdozent''. During this period, his deepening study of mathematics led him to consider several foundational problems in [[epistemology]] and the theory of science. These interests resulted in his first major work, ''Logical Investigations'' (1900-1901), which is considered to be the founding text of phenomenology. | |

| − | Husserl | + | |

| − | + | From 1901-1916 Husserl was a professor at the university in Göttingen where he published his next major work ''Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and a Phenomenological Philosophy, Volume One'' (1913). This text marked his development from the descriptive phenomenology of his earlier work to transcendental phenomenology. In 1916 Husserl went to Freiburg and became the chair in philosophy and took on several assistants, most notably [[Edith Stein]] and [[Martin Heidegger]], who were the editors of Husserl’s (in)famous ''Lectures on the Phenomenology of Internal Time-Consciousness'' (1928). Husserl also retired in 1928 and was succeeded by [[Martin Heidegger]] as the chair of the department in Freiburg. | |

| + | |||

| + | During the last five years of his life, Husserl fell prey to the [[anti-Semitism]] of the rising [[Nazism|Nazi]] party in Germany. In 1933 he was taken off the list of university professors and denied access to the university library. Amidst his marginalization from the university milieu in Germany during the 1930s, Husserl was invited to give lectures in Vienna and [[Prague]] in 1935. These lectures were developed to comprise his last major work, ''The Crisis of the European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology'' (1952). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Most of the books that Husserl published during his life were in essence programmatic introductions to phenomenology. But they constitute only a small portion of his vast writing. Because Husserl was in the habit of writing down his phenomenological reflections each day, he also left behind approximately 45,000 research manuscripts. When these manuscripts were deemed to be in jeopardy during the [[World War II|Second World War]], they were smuggled to a [[monastery]] in [[Belgium]]. Eventually, these manuscripts (along with other unpublished lectures, articles, and papers) were organized to create the Husserl-Archives, founded at the Institute of Philosophy in Leuven where they remain to this day. The Husserl-Archives continue to be published in a critical edition called ''Husserliana'' and continue to be a major source of phenomenological research. | ||

===Precursors and influences=== | ===Precursors and influences=== | ||

| − | * [[Skepticism]] (for the concept of | + | There are several precedents to Husserl’s formulation of the discipline of phenomenology. Even in [[ancient philosophy]], one can find the distinction between ''phainomenon'' (Greek for appearance) and “[[reality]],” a distinction that can be found in [[Plato]]’s allegory of the cave or [[Aristotle]]’s appearance [[syllogism]]s, for instance. The [[etymology]] of the term “phenomenology” comes from the compound of the Greek words ''phainomenon'' and ''[[logos]]'', literally meaning a rational account (''logos'') of the various ways in which things appear. One of the aspirations and advantages of phenomenology is its desire and unique ability to retrieve many of the decisive aspects of classical philosophy. |

| − | * [[Descartes]] (Methodological doubt, ''ego cogito'') | + | |

| − | * [[British empiricism]] (Locke, Hume, Berkeley, Mill) | + | In the eighteenth century, “phenomenology” was associated with the theory of appearances found in the analysis of sense [[perception]] of empirical knowledge. The term was employed by Johann Heinrich Lambert, a student of [[Christian Wolff]]. It was subsequently appropriated by [[Immanuel Kant]], [[Johann Gottlieb Fichte]], and [[Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel]]. By 1889 [[Franz Brentano]] (1838-1970) used the term to identify his “descriptive psychology.” Central to Brentano’s formulation of his descriptive psychology was the theory of [[intentionality]], a concept that he revived from [[scholasticism]] to identify the character of psychic phenomenon. Husserl, along with Alexius Meinong, Christian von Ehrenfels, Kasimir Twardowski, and Anton Marty, were students of Brentano in Vienna and their charismatic teacher exerted significant influence on them. Due to the centrality of the theory of intentionality in Husserl’s work, Brentano is considered to be the main forerunner of phenomenology. |

| − | * [[Immanuel Kant]] and [[ | + | |

| + | '''See also:''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | * [[Skepticism]] (for the concept of epoché) | ||

| + | * [[Rene Descartes]] (Methodological doubt, ''ego cogito'') | ||

| + | * [[British empiricism]] (Husserl had an special affinity for the works of Locke, Hume, Berkeley, Mill) | ||

| + | * [[Immanuel Kant]] and [[neo-Kantianism]] (one of Husserl's main opponents who nevertheless influenced his transcendental turn) | ||

* [[Franz Brentano]] (for the concept of intentionality and the method of descriptive psychology) | * [[Franz Brentano]] (for the concept of intentionality and the method of descriptive psychology) | ||

* [[Carl Stumpf]] (psychological analysis, influenced Husserl's early works) | * [[Carl Stumpf]] (psychological analysis, influenced Husserl's early works) | ||

| + | * [[William James]] (his ''Principles of Psychology'' (1891) greatly impressed Husserl and his "radical empiricism" bears a striking resemblance to phenomenology) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===The Early Husserl of ''Logical Investigations''=== | ||

| + | While ''Logical Investigations'' was not Husserl’s first published work, he considered it to be the first “breakthrough” in phenomenology. It is not only the founding text of phenomenology, but also one of the most important texts in twentieth century philosophy. It is comprised of a debate between ''psychologism'' and ''logicism'', a debate which forms the background to Husserl’s initial formulation of [[intentionality]]. [[Psychologism]] maintains that [[psychology]] should provide the theoretical foundation for [[epistemology]]. Because of the nature of [[perception|perceiving]], [[belief|believing]], and judging are psychic phenomenon, empirical investigations of psychology is the proper domain in which these forms of knowing ought to be investigated. According to psychologism, this applies to all scientific and logical reasoning. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For Husserl, this position overlooks the fundamental difference between the domain of [[logic]] and psychology. Logic is concerned with ideal objects and the laws that govern them and cannot be reduced to a subjective psychical process. Husserl argues that the ideal objects of logic and [[mathematics]] do not suffer the temporal change of psychic acts but remain trans-temporal and objective across multiple acts of various subjects. For example, 2 + 3 = 5 no matter how many times it is repeated or the various different people perform the operation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Thus, the fundamental error of psychologism is that it does not distinguish between the ''object'' of knowledge and the ''act'' of knowing. Logicism, on the other hand, is the view that these ideal objects and their laws constitute the foundation of knowing and remain totally autonomous from empirical conditions. Thus, the domain of logic is ''sui generis'' and does not need to trace back the structures of thinking back to pre-predicative experience of concrete objects in the world. Logicism fails, according to Husserl, because it does not take into account the ways in which subjective acts function in structuring ideal objectivity. | ||

| − | + | In order to account for the subjective processes of psychology and the ideal objectivity of logic, Husserl developed his theory of [[intentionality]]. Through it he tried to account for both acts of [[consciousness]] and the structure of ideal objects without reducing one to the other. By focusing on the relation or correlation between acts of consciousness and their objects, Husserl wanted to describe the ''[[a priori]]'' structure of these acts. In so doing, he suspended the [[metphysics|metaphysical]] status of these objects of experience. More specifically, through this process of bracketing metaphysical questions he attempted to carve out an epistemological position that was neither a metaphysical [[realism]] nor a metaphysical [[idealism]], but metaphysically neutral. | |

| − | |||

| − | ==Transcendental phenomenology | + | ===Transcendental phenomenology=== |

| − | + | As Husserl’s phenomenological investigations deepened, he began to develop the descriptive phenomenology of his earlier work into a transcendental phenomenology. This “transcendental turn” was accompanied by two methodological clarifications through the concepts of ''epoché'' and ''reduction''. The epoché is a methodological shift in one’s attitude from naively accepting certain dogmatic beliefs about the world to “bracketing” or suspending those beliefs in order to discover their true sense. It is analogous to the mathematical procedure of taking the absolute value of a certain number, e.g., taking the number 2 and indexing it - [2]. When one brackets the natural attitude, they are, in essence, bracketing its common place validity in order to discover its meaning. Reduction, on the other hand, is the term Husserl eventually used to describe the thematization of the relation between subjectivity and the world. In its literal sense, to re-duce one’s natural experience is “to lead back” one’s attention to the universal and necessary conditions of that experience. Both epoché and reduction are important features in freeing oneself from naturalistic dogmaticism in order to illuminate the contribution that subjectivity plays in the constitution of meaning. For this reason, transcendental phenomenology is also often called ''constitutive'' phenomenology. | |

| − | + | The transcendental turn in phenomenology is perhaps the most controversial and contested aspect of the discipline. Husserl first developed it in ''Ideas I'', which remains one of his most criticized works. It has most notably been critiqued by [[Martin Heidegger]], [[Maurice Merleau-Ponty]], and [[Paul Ricoeur]] who saw it as a reversion to a kind of [[idealism]] along the lines of [[Immanuel Kant|Kant]] or [[Johnn Gottlieb Fichte|Fichte]]. Others have argued that Husserl’s idealism during this period of his research does not forego the epistemological realism of his early work. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Genetic Phenomenology=== | |

| + | Husserl’s later work can be characterized by what he called ''genetic phenomenology'', which was a further broadening of the scope of phenomenological analysis. Genetic phenomenology can best be described in contrast to ''static phenomenology'', a distinction that Husserl made as early as 1917. Static phenomenology is the style of analysis that is found in the ''Logical Investigations'' and ''Ideas I'', for instance, and primarily focuses on the fixed intentional relation between an act and an object. It is usually confined to a certain domain of experience (whether it be ideal objects or physical objects, etc.) and is static in that the objects of investigation are readily available and “frozen” in time. But Husserl eventually became concerned with the ''origin'' and ''history'' of these objects. The experience of various objects or state of affairs includes patterns of understanding which color these experiences, a process that Husserl calls ''sedimentation''. This is the process by which previous experiences come to shape and condition others. Genetic phenomenology attempts to explore the origin and history of this process in any given set of experiences. | ||

| − | + | This phenomenological approach is most typified in the work that occupied Husserl in the years before his death, ''The Crisis of the European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology'' (1952). In it, along with other works from this period, can be found the following concepts that occupy a central role in his genetic analysis: | |

| − | + | * Intersubjectivity | |

| + | * History | ||

| + | * Life-world | ||

| + | * Embodiment | ||

| + | * Tradition | ||

==Realist phenomenology== | ==Realist phenomenology== | ||

| − | After Husserl's publication of the '' | + | After Husserl's publication of the ''Ideas I'', many phenomenologists took a critical stance towards his new theories. Members of the Munich group especially distanced themselves from his new "transcendental phenomenology" and preferred the earlier "realist phenomenology" of the first edition of the ''Logical Investigations''. |

| − | + | Realistic phenomenology emphasizes the search for the essential structures of various concrete situations. [[Adolf Reinach]] extended phenomenology to the field of the [[philosophy of law]]; [[Max Scheler]] added [[ethics]], [[religion]], and [[philosophical anthropology]]; [[Edith Stein]] focused on human sciences and [[gender]]; and [[Roman Ingarden]] expanded phenomenology to various themes in [[aesthetics]]. Other realist phenomenologists include: Alexander Pfänder, Johannnes Daubert, [[Nicolai Hartmann]], [[Herbert Spiegelberg]], Karl Schuhmann, and Barry Smith. | |

==Existential phenomenology== | ==Existential phenomenology== | ||

| − | Existential phenomenology | + | While [[existentialism]] has a precedent in the writings of [[Søren Kierkegaard]], [[Friedrich Nietzsche]], and [[Fyodor Dostoevsky]], it was not until Heidegger’s publication of ''Being and Time'' (1927) that many existential themes were incorporated into the phenomenological tradition. Existential phenomenology undergoes an investigation of meaning in the context of lived experience. Its central claim is that the proper site of phenomenological investigation is not a theoretical exercise focused on the cognitive features of knowledge. Rather the ultimate ground of meaning is found in what it means to be, which is a question that can only be posed in the context of the ordinary and everyday experience of one’s own existence. Because of its emphasis on the practical concerns of everyday life, existential phenomenology has enjoyed much attention in literary and popular circles. |

| + | |||

| + | ===Heidegger and German Existential Phenomenology=== | ||

| + | While [[Martin Heidegger|Heidegger]] vehemently resisted the label of [[existentialism]], his central work ''Being and Time'' (1927) is considered to be the central inspiration for subsequent articulations of existential phenomenology. As a student and eventual successor of Husserl, Heidegger had first hand exposure to the various dimensions of phenomenological investigation and he incorporated much of them in his own work. For example, Heidegger’s conception of ''being-in-the-world'' is considered to be an elaboration of Husserl’s theory of [[intentionality]] within a practical sphere. Heidegger, however, did not consider this practical dimension of intentionality to be just one among others. Rather he claimed that one’s “average everyday” comportment to the world is the ultimate intentional relation upon which all others are grounded or rooted. | ||

| − | + | Heidegger also approached Husserl’s phenomenology with a particular question in mind. It was a question that he began to ask after he read [[Franz Brentano]]’s ''On The Manifold Meanings of Being in Aristotle'' in his high school years. Heidegger saw in phenomenology the potential to re-interpret one of the seminal issues of the [[metaphysics|metaphysical]] tradition of which Husserl had been so critical: ''[[ontology]]''. Ontology is the study of being ''qua'' being (being as opposed to being''s'' or things) and Heidegger’s reactivation of the question of being had become a watershed event in twentieth-century philosophy. However, because the question of being had become concealed within the degenerative tradition of Western [[metaphysics]], Heidegger had to provide a preparatory analysis in order to avoid the trappings of that tradition. This preparatory analysis is the task of ''Being and Time'', which is an investigation of one particular but unique being—''Dasein'' ([[German language|German]]; literally, ''being-there''). | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Heidegger was well aware of the circular reasoning that often occurs when approaching ontology and thus he was forced to ask the question, “How can we appropriately inquire into the nature of being when our ontological pre-conceptions inevitably pre-determine the investigation from the start?” In order to adequately approach the question of being with a transparent view of these pre-conceptions, Heidegger examined the way in which being becomes an issue in the first place. This is role of ''Dasein''—the entity “that we ourselves are” when being becomes an issue. ''Dasein'' is the one who inquires into the nature of being, the one for whom being is an issue. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Thus, ''Being and Time'' is an investigation of the mode in which ''Dasein'' has its being-in-the-world. Heidegger’s famous analysis of ''Dasein''’s existence in the context of practical concerns, [[anxiety]], [[temporality]], and [[historicity]] influenced many existential phenomenologists in [[Germany]]. Most notable among them are [[Karl Jaspers]] and [[Hannah Arendt]]. | |

| − | + | While Husserl attempted to explicate the [[essence|essential]] characteristics and structures of each kind of experience, Heidegger averted his phenomenological studies from an essentialist orientation of Husserl. For Heidegger, understanding always involves an element of [[Hermeneutics|interpretation]]. Heidegger characterized his phenomenology as “hermeneutic phenomenology.” In ''Being and Time'', Heidegger tried to explicate the structures of how ''Dasein'' interprets its sense of being. [[Hans-Georg Gadamer]] pursued the idea of the universality of hermeneutics inherent in Heidegger’s phenomenology. | |

| − | Existential | + | ===Sartre and French Existential Phenomenology=== |

| + | During the [[World War II|Second World War]], French philosophy became increasingly interested in solidifying the theoretical underpinnings of the [[dialectical materialism]] of [[Marxism]]. In order to do so they turned to [[Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel|Hegel]]’s ''Phenomenology of Spirit'', a text that exercised a considerable influence on Marx’s development of [[socialism]]. This new wave of Hegel scholarship (typified by [[Jean Wahl]], [[Alexandre Koyré]], [[Alexandre Kojève]], [[Jean Hyppolite]]) incorporated many themes of Husserlian and Heideggerian phenomenology. In particular, Kojève’s famous lectures at the ''École Pratique des Hautes Études'' from 1933 to 1939 (published in part in ''Introduction to the Reading of Hegel'') were extremely influential in inaugurating an interest in phenomenology. Many of the attendants of these lectures became the leading philosophers of the next generation, including: [[Maurice Merleau-Ponty]], [[Claude Lévi-Strauss]], [[Jacques Lacan]], and [[George Bataille]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The most influential of all was undoubtedly [[Jean-Paul Sartre]] whose ''Being and Nothingness: A Phenomenological Essay on Ontology'' (1944) seemed to capture the sentiment of post-war [[France]]. For Sartre, [[ontology]] should be considered through a phenomenological description and classification of the ultimate origin and end of meaning in the lives of individuals and the universe as a whole. His descriptive method starts from the most general sense of meaning and ends with the most concrete forms that meaning takes. In this most general sense, Sartre analyzes two fundamental aspects of being: the in-itself (''en-soi'') and the for-itself (''pour-soi''), which many consider to be equivalent to the non-conscious and [[consciousness]] respectively. Later in the book, Sartre adds another aspect of being, the for-others (''pour-autrui''), which examines the social dimension of existence. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1944 Sartre gave a public lecture entitled “Existentialism is a Humanism” which is considered the manifesto of twentieth-century [[existentialism]]. He was also the founder (along with [[Simone de Beauvoir]]) of the influential journal ''Les Temps Modernes'', a monthly review of literature and politics. Other central figures who played a decisive role in introducing phenomenology to France were [[Emmanuel Levinas]], [[Maurice Merleau-Ponty]], and [[Gabriel Marcel]]. | ||

==Criticisms of phenomenology== | ==Criticisms of phenomenology== | ||

| − | + | Daniel Dennett has criticized phenomenology on the basis that its explicitly first-person approach is incompatible with the scientific third-person approach, going so far as to coin the term ''autophenomenology'' to emphasize this aspect and to contrast it with his own alternative, which he calls heterophenomenology. | |

==Currents influenced by phenomenology == | ==Currents influenced by phenomenology == | ||

| Line 82: | Line 101: | ||

* [[Personhood Theory]] | * [[Personhood Theory]] | ||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | * | + | * Edie, James M. (ed.). 1965. ''An Invitation to Phenomenology''. Chicago: Quadrangle Books. ISBN 0812960823 <small>A collection of seminal phenomenological essays.</small> |

| − | * | + | * Elveton, R. O. (ed.). 1970. ''The Phenomenology of Husserl: Selected Critical Readings''. Second reprint edition, 2003. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0970167903 <small>Key essays about Husserl's phenomenology.</small> |

| − | * | + | * Hammond, Michael, Jane Howarth, and Russell Kent. 1991. ''Understanding Phenomenology''. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 063113283X |

| − | * | + | * Luijpen, William A., and Henry J. Koren. 1969. ''A First Introduction to Existential Phenomenology''. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press. ISBN 0820701106 |

| − | * David | + | * Macann, Christopher. 1993. ''Four Phenomenological Philosophers: Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty''. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415073545 |

| − | * | + | * Moran, Dermot. 2000. ''Introduction to Phenomenology''. Oxford: Routledge. ISBN 0415183731 <small>Charting phenomenology from Brentano, through Husserl and Heidegger, to Gadamer, Arendt, Levinas, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty and Derrida.</small> |

| − | + | * Sokolowski, Robert. 2000. ''Introduction to Phenomenology''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521667925 <small>An excellent non-historical introduction to phenomenology.</small> | |

| − | + | * Spiegelberg, Herbert. 1965. ''The Phenomenological Movement: A Historical Introduction''. Third edition, Springer. ISBN 9024725356 <small>The most comprehensive and thorough source on the entire phenomenological movement. Unfortunately, it is expensive and hard to find.</small> | |

| − | + | * Stewart, David and Algis Mickunas. 1974. ''Exploring Phenomenology: A Guide to the Field and its Literature''. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1990. ISBN 082140962X | |

| − | + | * Thévenaz, Pierre. 1962. ''What is Phenomenology?'' Chicago: Quadrangle Books. New edition, Times Books, 2000. ISBN 0812960009 | |

| − | + | * Zaner, Richard M. 1970. ''The Way of Phenomenology''. Indianapolis, IN: Pegasus. | |

| − | * | + | * Zaner, Richard and Don Ihde (eds.). 1973. ''Phenomenology and Existentialism''. New York: Putnam. ISBN 039910951X <small>Contains many key essays in existential phenomenology.</small> |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==External links== |

| − | + | All links retrieved November 23, 2022. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * [http://www.husserlpage.com/ The Husserl Page] | |

| − | + | * [https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/phenomenology/ Phenomenology] ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' | |

| − | |||

| − | * [http://www.husserlpage.com/ | ||

| − | * [ | ||

| − | |||

* [http://www.phenomenology.ro Romanian Society for Phenomenology] | * [http://www.phenomenology.ro Romanian Society for Phenomenology] | ||

| + | * [https://ophen.org/series-1169 Bulletin d'analyse phénoménologique] | ||

| + | * [https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rbsp20 Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology] | ||

| + | * [https://brill.com/view/journals/rip/rip-overview.xml Research in Phenomenology] | ||

| + | * [https://newsletter-phenomenology.ophen.org/ Newsletter of Phenomenology] | ||

| − | + | ===General Philosophy Sources=== | |

| + | *[http://plato.stanford.edu/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy] | ||

| + | *[http://www.bu.edu/wcp/PaidArch.html Paideia Project Online] | ||

| + | *[http://www.iep.utm.edu/ The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy] | ||

| + | *[http://www.gutenberg.org/ Project Gutenberg] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Philosophy]] | [[Category:Philosophy]] | ||

[[Category:Social philosophy]] | [[Category:Social philosophy]] | ||

Latest revision as of 02:57, 24 November 2022

Phenomenology is, in its founder Edmund Husserl's formulation, the study of experience and the ways in which things present themselves in and through experience. Taking its starting point from the first-person perspective, phenomenology attempts to describe the essential features or structures of a given experience or any experience in general. One of the central structures of any experience is its intentionality, or its being directed toward some object or state of affairs. The theory of intentionality, the central theme of phenomenology, maintains that all experience necessarily has this object-relatedness and thus one of the catch phrases of phenomenology is “all consciousness is consciousness of.” In short, in our experiences we are always already related to the world and to overlook this fact is to commit one of the cardinal sins of phenomenology: abstraction.

This emphasis on the intentional structure of experience makes phenomenology distinctive from other modern epistemological approaches that have a strong separation between the experiencing subject and the object experienced. Starting with Rene Descartes, this subject/object distinction produced the traditions of rationalism and empiricism which focus on one of these aspects of experience at the expense of the other. Phenomenology seeks to offer a corrective to these traditions by providing an account of how the experiencing subject and object experienced are not externally related, but internally unified. This unified relation between the subject and object is the “phenomena” that phenomenology takes as the starting point of its descriptive analysis.

The discipline of phenomenology as a historical movement originates with Edmund Husserl (1859-1938). He is considered the “father” of phenomenology and worked copiously to establish it as a rigorous science. It continued to develop in twentieth-century European philosophy through the works of Max Scheler, Martin Heidegger, Hannah Arendt, Jean-Paul Sartre, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Paul Ricoeur, Emmanuel Levinas, Jacques Derrida, and Jean-Luc Marion. Given its continual development and appropriation in various other disciplines (most notably - ontology, sociology, psychology, ecology, ethics, theology, philosophy of mind) it is considered to be one of the most significant philosophical movements in the twentieth century.

Husserl - The Father of Phenomenology

Edmund Husserl was born on April 8, 1859, into a Jewish family living in the Austrian Empire. He began his academic career as a mathematician, defending his doctoral dissertation in Vienna in 1882. While in Vienna, he attended lectures by the prominent psychologist and philosopher Franz Brentano, who was exercise a considerable influence on Husserl in the years to come.

In 1886 Husserl converted to Protestantism and the following year he defended his Habilitation on the concept of number at the university in Halle, where he was to spend the next fourteen years as Privatdozent. During this period, his deepening study of mathematics led him to consider several foundational problems in epistemology and the theory of science. These interests resulted in his first major work, Logical Investigations (1900-1901), which is considered to be the founding text of phenomenology.

From 1901-1916 Husserl was a professor at the university in Göttingen where he published his next major work Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and a Phenomenological Philosophy, Volume One (1913). This text marked his development from the descriptive phenomenology of his earlier work to transcendental phenomenology. In 1916 Husserl went to Freiburg and became the chair in philosophy and took on several assistants, most notably Edith Stein and Martin Heidegger, who were the editors of Husserl’s (in)famous Lectures on the Phenomenology of Internal Time-Consciousness (1928). Husserl also retired in 1928 and was succeeded by Martin Heidegger as the chair of the department in Freiburg.

During the last five years of his life, Husserl fell prey to the anti-Semitism of the rising Nazi party in Germany. In 1933 he was taken off the list of university professors and denied access to the university library. Amidst his marginalization from the university milieu in Germany during the 1930s, Husserl was invited to give lectures in Vienna and Prague in 1935. These lectures were developed to comprise his last major work, The Crisis of the European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology (1952).

Most of the books that Husserl published during his life were in essence programmatic introductions to phenomenology. But they constitute only a small portion of his vast writing. Because Husserl was in the habit of writing down his phenomenological reflections each day, he also left behind approximately 45,000 research manuscripts. When these manuscripts were deemed to be in jeopardy during the Second World War, they were smuggled to a monastery in Belgium. Eventually, these manuscripts (along with other unpublished lectures, articles, and papers) were organized to create the Husserl-Archives, founded at the Institute of Philosophy in Leuven where they remain to this day. The Husserl-Archives continue to be published in a critical edition called Husserliana and continue to be a major source of phenomenological research.

Precursors and influences

There are several precedents to Husserl’s formulation of the discipline of phenomenology. Even in ancient philosophy, one can find the distinction between phainomenon (Greek for appearance) and “reality,” a distinction that can be found in Plato’s allegory of the cave or Aristotle’s appearance syllogisms, for instance. The etymology of the term “phenomenology” comes from the compound of the Greek words phainomenon and logos, literally meaning a rational account (logos) of the various ways in which things appear. One of the aspirations and advantages of phenomenology is its desire and unique ability to retrieve many of the decisive aspects of classical philosophy.

In the eighteenth century, “phenomenology” was associated with the theory of appearances found in the analysis of sense perception of empirical knowledge. The term was employed by Johann Heinrich Lambert, a student of Christian Wolff. It was subsequently appropriated by Immanuel Kant, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. By 1889 Franz Brentano (1838-1970) used the term to identify his “descriptive psychology.” Central to Brentano’s formulation of his descriptive psychology was the theory of intentionality, a concept that he revived from scholasticism to identify the character of psychic phenomenon. Husserl, along with Alexius Meinong, Christian von Ehrenfels, Kasimir Twardowski, and Anton Marty, were students of Brentano in Vienna and their charismatic teacher exerted significant influence on them. Due to the centrality of the theory of intentionality in Husserl’s work, Brentano is considered to be the main forerunner of phenomenology.

See also:

- Skepticism (for the concept of epoché)

- Rene Descartes (Methodological doubt, ego cogito)

- British empiricism (Husserl had an special affinity for the works of Locke, Hume, Berkeley, Mill)

- Immanuel Kant and neo-Kantianism (one of Husserl's main opponents who nevertheless influenced his transcendental turn)

- Franz Brentano (for the concept of intentionality and the method of descriptive psychology)

- Carl Stumpf (psychological analysis, influenced Husserl's early works)

- William James (his Principles of Psychology (1891) greatly impressed Husserl and his "radical empiricism" bears a striking resemblance to phenomenology)

The Early Husserl of Logical Investigations

While Logical Investigations was not Husserl’s first published work, he considered it to be the first “breakthrough” in phenomenology. It is not only the founding text of phenomenology, but also one of the most important texts in twentieth century philosophy. It is comprised of a debate between psychologism and logicism, a debate which forms the background to Husserl’s initial formulation of intentionality. Psychologism maintains that psychology should provide the theoretical foundation for epistemology. Because of the nature of perceiving, believing, and judging are psychic phenomenon, empirical investigations of psychology is the proper domain in which these forms of knowing ought to be investigated. According to psychologism, this applies to all scientific and logical reasoning.

For Husserl, this position overlooks the fundamental difference between the domain of logic and psychology. Logic is concerned with ideal objects and the laws that govern them and cannot be reduced to a subjective psychical process. Husserl argues that the ideal objects of logic and mathematics do not suffer the temporal change of psychic acts but remain trans-temporal and objective across multiple acts of various subjects. For example, 2 + 3 = 5 no matter how many times it is repeated or the various different people perform the operation.

Thus, the fundamental error of psychologism is that it does not distinguish between the object of knowledge and the act of knowing. Logicism, on the other hand, is the view that these ideal objects and their laws constitute the foundation of knowing and remain totally autonomous from empirical conditions. Thus, the domain of logic is sui generis and does not need to trace back the structures of thinking back to pre-predicative experience of concrete objects in the world. Logicism fails, according to Husserl, because it does not take into account the ways in which subjective acts function in structuring ideal objectivity.

In order to account for the subjective processes of psychology and the ideal objectivity of logic, Husserl developed his theory of intentionality. Through it he tried to account for both acts of consciousness and the structure of ideal objects without reducing one to the other. By focusing on the relation or correlation between acts of consciousness and their objects, Husserl wanted to describe the a priori structure of these acts. In so doing, he suspended the metaphysical status of these objects of experience. More specifically, through this process of bracketing metaphysical questions he attempted to carve out an epistemological position that was neither a metaphysical realism nor a metaphysical idealism, but metaphysically neutral.

Transcendental phenomenology

As Husserl’s phenomenological investigations deepened, he began to develop the descriptive phenomenology of his earlier work into a transcendental phenomenology. This “transcendental turn” was accompanied by two methodological clarifications through the concepts of epoché and reduction. The epoché is a methodological shift in one’s attitude from naively accepting certain dogmatic beliefs about the world to “bracketing” or suspending those beliefs in order to discover their true sense. It is analogous to the mathematical procedure of taking the absolute value of a certain number, e.g., taking the number 2 and indexing it - [2]. When one brackets the natural attitude, they are, in essence, bracketing its common place validity in order to discover its meaning. Reduction, on the other hand, is the term Husserl eventually used to describe the thematization of the relation between subjectivity and the world. In its literal sense, to re-duce one’s natural experience is “to lead back” one’s attention to the universal and necessary conditions of that experience. Both epoché and reduction are important features in freeing oneself from naturalistic dogmaticism in order to illuminate the contribution that subjectivity plays in the constitution of meaning. For this reason, transcendental phenomenology is also often called constitutive phenomenology.

The transcendental turn in phenomenology is perhaps the most controversial and contested aspect of the discipline. Husserl first developed it in Ideas I, which remains one of his most criticized works. It has most notably been critiqued by Martin Heidegger, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Paul Ricoeur who saw it as a reversion to a kind of idealism along the lines of Kant or Fichte. Others have argued that Husserl’s idealism during this period of his research does not forego the epistemological realism of his early work.

Genetic Phenomenology

Husserl’s later work can be characterized by what he called genetic phenomenology, which was a further broadening of the scope of phenomenological analysis. Genetic phenomenology can best be described in contrast to static phenomenology, a distinction that Husserl made as early as 1917. Static phenomenology is the style of analysis that is found in the Logical Investigations and Ideas I, for instance, and primarily focuses on the fixed intentional relation between an act and an object. It is usually confined to a certain domain of experience (whether it be ideal objects or physical objects, etc.) and is static in that the objects of investigation are readily available and “frozen” in time. But Husserl eventually became concerned with the origin and history of these objects. The experience of various objects or state of affairs includes patterns of understanding which color these experiences, a process that Husserl calls sedimentation. This is the process by which previous experiences come to shape and condition others. Genetic phenomenology attempts to explore the origin and history of this process in any given set of experiences.

This phenomenological approach is most typified in the work that occupied Husserl in the years before his death, The Crisis of the European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology (1952). In it, along with other works from this period, can be found the following concepts that occupy a central role in his genetic analysis:

- Intersubjectivity

- History

- Life-world

- Embodiment

- Tradition

Realist phenomenology

After Husserl's publication of the Ideas I, many phenomenologists took a critical stance towards his new theories. Members of the Munich group especially distanced themselves from his new "transcendental phenomenology" and preferred the earlier "realist phenomenology" of the first edition of the Logical Investigations.

Realistic phenomenology emphasizes the search for the essential structures of various concrete situations. Adolf Reinach extended phenomenology to the field of the philosophy of law; Max Scheler added ethics, religion, and philosophical anthropology; Edith Stein focused on human sciences and gender; and Roman Ingarden expanded phenomenology to various themes in aesthetics. Other realist phenomenologists include: Alexander Pfänder, Johannnes Daubert, Nicolai Hartmann, Herbert Spiegelberg, Karl Schuhmann, and Barry Smith.

Existential phenomenology

While existentialism has a precedent in the writings of Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Fyodor Dostoevsky, it was not until Heidegger’s publication of Being and Time (1927) that many existential themes were incorporated into the phenomenological tradition. Existential phenomenology undergoes an investigation of meaning in the context of lived experience. Its central claim is that the proper site of phenomenological investigation is not a theoretical exercise focused on the cognitive features of knowledge. Rather the ultimate ground of meaning is found in what it means to be, which is a question that can only be posed in the context of the ordinary and everyday experience of one’s own existence. Because of its emphasis on the practical concerns of everyday life, existential phenomenology has enjoyed much attention in literary and popular circles.

Heidegger and German Existential Phenomenology

While Heidegger vehemently resisted the label of existentialism, his central work Being and Time (1927) is considered to be the central inspiration for subsequent articulations of existential phenomenology. As a student and eventual successor of Husserl, Heidegger had first hand exposure to the various dimensions of phenomenological investigation and he incorporated much of them in his own work. For example, Heidegger’s conception of being-in-the-world is considered to be an elaboration of Husserl’s theory of intentionality within a practical sphere. Heidegger, however, did not consider this practical dimension of intentionality to be just one among others. Rather he claimed that one’s “average everyday” comportment to the world is the ultimate intentional relation upon which all others are grounded or rooted.

Heidegger also approached Husserl’s phenomenology with a particular question in mind. It was a question that he began to ask after he read Franz Brentano’s On The Manifold Meanings of Being in Aristotle in his high school years. Heidegger saw in phenomenology the potential to re-interpret one of the seminal issues of the metaphysical tradition of which Husserl had been so critical: ontology. Ontology is the study of being qua being (being as opposed to beings or things) and Heidegger’s reactivation of the question of being had become a watershed event in twentieth-century philosophy. However, because the question of being had become concealed within the degenerative tradition of Western metaphysics, Heidegger had to provide a preparatory analysis in order to avoid the trappings of that tradition. This preparatory analysis is the task of Being and Time, which is an investigation of one particular but unique being—Dasein (German; literally, being-there).

Heidegger was well aware of the circular reasoning that often occurs when approaching ontology and thus he was forced to ask the question, “How can we appropriately inquire into the nature of being when our ontological pre-conceptions inevitably pre-determine the investigation from the start?” In order to adequately approach the question of being with a transparent view of these pre-conceptions, Heidegger examined the way in which being becomes an issue in the first place. This is role of Dasein—the entity “that we ourselves are” when being becomes an issue. Dasein is the one who inquires into the nature of being, the one for whom being is an issue.

Thus, Being and Time is an investigation of the mode in which Dasein has its being-in-the-world. Heidegger’s famous analysis of Dasein’s existence in the context of practical concerns, anxiety, temporality, and historicity influenced many existential phenomenologists in Germany. Most notable among them are Karl Jaspers and Hannah Arendt.

While Husserl attempted to explicate the essential characteristics and structures of each kind of experience, Heidegger averted his phenomenological studies from an essentialist orientation of Husserl. For Heidegger, understanding always involves an element of interpretation. Heidegger characterized his phenomenology as “hermeneutic phenomenology.” In Being and Time, Heidegger tried to explicate the structures of how Dasein interprets its sense of being. Hans-Georg Gadamer pursued the idea of the universality of hermeneutics inherent in Heidegger’s phenomenology.

Sartre and French Existential Phenomenology

During the Second World War, French philosophy became increasingly interested in solidifying the theoretical underpinnings of the dialectical materialism of Marxism. In order to do so they turned to Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, a text that exercised a considerable influence on Marx’s development of socialism. This new wave of Hegel scholarship (typified by Jean Wahl, Alexandre Koyré, Alexandre Kojève, Jean Hyppolite) incorporated many themes of Husserlian and Heideggerian phenomenology. In particular, Kojève’s famous lectures at the École Pratique des Hautes Études from 1933 to 1939 (published in part in Introduction to the Reading of Hegel) were extremely influential in inaugurating an interest in phenomenology. Many of the attendants of these lectures became the leading philosophers of the next generation, including: Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Jacques Lacan, and George Bataille.

The most influential of all was undoubtedly Jean-Paul Sartre whose Being and Nothingness: A Phenomenological Essay on Ontology (1944) seemed to capture the sentiment of post-war France. For Sartre, ontology should be considered through a phenomenological description and classification of the ultimate origin and end of meaning in the lives of individuals and the universe as a whole. His descriptive method starts from the most general sense of meaning and ends with the most concrete forms that meaning takes. In this most general sense, Sartre analyzes two fundamental aspects of being: the in-itself (en-soi) and the for-itself (pour-soi), which many consider to be equivalent to the non-conscious and consciousness respectively. Later in the book, Sartre adds another aspect of being, the for-others (pour-autrui), which examines the social dimension of existence.

In 1944 Sartre gave a public lecture entitled “Existentialism is a Humanism” which is considered the manifesto of twentieth-century existentialism. He was also the founder (along with Simone de Beauvoir) of the influential journal Les Temps Modernes, a monthly review of literature and politics. Other central figures who played a decisive role in introducing phenomenology to France were Emmanuel Levinas, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Gabriel Marcel.

Criticisms of phenomenology

Daniel Dennett has criticized phenomenology on the basis that its explicitly first-person approach is incompatible with the scientific third-person approach, going so far as to coin the term autophenomenology to emphasize this aspect and to contrast it with his own alternative, which he calls heterophenomenology.

Currents influenced by phenomenology

- Phenomenology of religion

- Hermeneutics

- Structuralism

- Poststructuralism

- Existentialism

- Deconstruction

- Philosophy of technology

- Emergy

- Personhood Theory

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Edie, James M. (ed.). 1965. An Invitation to Phenomenology. Chicago: Quadrangle Books. ISBN 0812960823 A collection of seminal phenomenological essays.

- Elveton, R. O. (ed.). 1970. The Phenomenology of Husserl: Selected Critical Readings. Second reprint edition, 2003. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0970167903 Key essays about Husserl's phenomenology.

- Hammond, Michael, Jane Howarth, and Russell Kent. 1991. Understanding Phenomenology. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 063113283X

- Luijpen, William A., and Henry J. Koren. 1969. A First Introduction to Existential Phenomenology. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press. ISBN 0820701106

- Macann, Christopher. 1993. Four Phenomenological Philosophers: Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415073545

- Moran, Dermot. 2000. Introduction to Phenomenology. Oxford: Routledge. ISBN 0415183731 Charting phenomenology from Brentano, through Husserl and Heidegger, to Gadamer, Arendt, Levinas, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty and Derrida.

- Sokolowski, Robert. 2000. Introduction to Phenomenology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521667925 An excellent non-historical introduction to phenomenology.

- Spiegelberg, Herbert. 1965. The Phenomenological Movement: A Historical Introduction. Third edition, Springer. ISBN 9024725356 The most comprehensive and thorough source on the entire phenomenological movement. Unfortunately, it is expensive and hard to find.

- Stewart, David and Algis Mickunas. 1974. Exploring Phenomenology: A Guide to the Field and its Literature. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1990. ISBN 082140962X

- Thévenaz, Pierre. 1962. What is Phenomenology? Chicago: Quadrangle Books. New edition, Times Books, 2000. ISBN 0812960009

- Zaner, Richard M. 1970. The Way of Phenomenology. Indianapolis, IN: Pegasus.

- Zaner, Richard and Don Ihde (eds.). 1973. Phenomenology and Existentialism. New York: Putnam. ISBN 039910951X Contains many key essays in existential phenomenology.

External links

All links retrieved November 23, 2022.

- The Husserl Page

- Phenomenology Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Romanian Society for Phenomenology

- Bulletin d'analyse phénoménologique

- Journal of the British Society for Phenomenology

- Research in Phenomenology

- Newsletter of Phenomenology

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.