Greek philosophy, Ancient

Ancient Western philosophy designates the philosophy from around the sixth century B.C.E. to the sixth century C.E.. This period became important because of three great thinkers, Socrates (fifth century B.C.E.), his student Plato (fourth century B.C.E.), and Plato's student Aristotle (fourth century B.C.E.). They laid the foundation of Western philosophy by exploring and defining the range, scope, method, terminology, and problematics of philosophical inquiry.

Ancient Western philosophy is generally divided into three periods centering on them: the fist, the period prior to Socrates, all thinkers prior to Socrates are called PreSocratics; second, the period of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle; and the last, the period that covers diverse philosophy after them, which includes Stoics, Epicureans, Skeptics in Hellenistic age, and Neo-Platonists, Aristotelians under Roman Empire. Spread of christianity ushered the end of Ancient Philosophy in the sixth century C.E.

Pre-Socratic philosophers

Greek philosophers prior to Socrates are called "Pre-Socratics" or "pre-Socratic philosophers." They were the earliest Western philosophers, active during the fifth and sixth centuries B.C.E. in ancient Greece. These philosophers tried to discover principles that could uniformly, consistently, and comprehensively explain all natural phenomena and the events in human life without resorting to mythology. They initiated a new method of explanation known as philosophy which has continued in use until the present day, and developed their thoughts primarily within the framework of cosmology and cosmogony.

Socrates was a pivotal philosopher who shifted the central focus of philosophy from cosmology to ethics and morality. Although some of these earlier philosophers were contemporary with, or even younger than Socrates, they were considered pre-Socratics (or early Greek Philosophers) according to the classification defined by Aristotle. The term "Pre-Socratics" became standard since H. Diels' (1848 - 1922) publication of "Fragmente der Vorsokratiker," the standard collection of fragments of pre-Socratics.

It is assumed that there were rich philosophical components in religious traditions of Judaism and Ancient Egyptian cultures, and some continuity of thought from these earlier traditions to pre-Socratics is also assumed. Although we do not have much information sources about their continuity, Proclus, fifth century Neo-Platonist, noted that the earliest philosophy such as Thales studied geometry in Egypt.

The pre-Socratic style of thought is often called natural philosophy, but their concept of nature was much broader than ours, encompassing spiritual and mythical as well as aesthetic and physical elements. They brought human thought to a new level of abstraction; raised a number of central questions of ontology, which are still relevant today; and cultivated the human spirit so as to open our eyes to the eternal truth. Primary sources for their philosophical discourses have all been lost except in a fragmentary form preserved in the works of various doxographers, and the best source is Aristotle. Although Aristotle’s interpretation of their thought dominated for centuries, modern scholars have gone beyond Aristotle to identify the original and unique contributions of the pre-Socratics.

In Athens, cultural activities such as tragedy flourished around fourth and fifth century B.C.E. Early philosophical activities, however, emerged in Eastern colonies of Asia Minor and Western Italian colonies.

Ionians

The first known philosophical activities flourished in Ionia. They inquired into "Arche," the ultimate origin or the first principle of things in nature. Thales of Miletus (about 640 B.C.E.) was known as the first philosopher. He identified "water" as the ultimate origin, and held that all other beings were consisted of this ultimate element. Since no information source is available except short fragments, we do not know much about his reasoning. We can only speculate a number of reasons why he identified water as the universal, original element: water can take three forms (liquid, gas, slid) in natural temperatures; circulation of water is vital to changes in nature; the vital element of life; often used for religious rituals such as "purification."

Italians

Heraclitus of Ephesus

Xenophanes

Parmenides and the other Eleatic philosophers

Leucippus, Democritus and the other Atomists

Protagoras and the Sophists

Empedocles

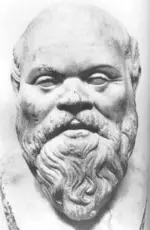

Socrates

Socrates, an Athenian philosopher, believed that a person should always try to do well. He believed that one should "know thyself." This is evidenced by the inscription at the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. He claimed that one has an obligation to disobey a bad command. He made his most important contribution to Western thought through his method of inquiry. In addition, he also taught many famous Greek philosophers. His most famous pupil was Plato. However, since Socrates discussed ideas that upset many people (some in high positions), he was sentenced to death by drinking the poison hemlock. The ironic thing about this is that during the reign of the Thirty Tyrants he was often threatened, but survived despite his continued protests for democracy. When democracy came, he was executed for corrupting their young. Most of what we know about Socrates came from Plato as Socrates wrote nothing down.

Plato and Aristotle

Aristotle, known as Aristoteles in most languages other than English (Aristotele in Italian), (384 B.C.E. - March 7, 322 B.C.E.) has, along with Plato, the reputation of one of the two most influential philosophers in Western thought.

Their works, although connected in many fundamental ways, differ considerably in both style and substance. Plato wrote several dozen philosophical dialogues—arguments in the form of conversations, usually with Socrates as a participant—and a few letters. Though the early dialogues deal mainly with methods of acquiring knowledge, and most of the last ones with justice and practical ethics, his most famous works expressed a synoptic view of ethics, metaphysics, reason, knowledge, and human life. Predominant ideas include the notion that knowledge gained through the senses always remains confused and impure, and that the contemplative soul that turns away from the world can acquire "true" knowledge. The soul alone can have knowledge of the Forms, the real essences of things, of which the world we see is but an imperfect copy. Such knowledge has ethical as well as scientific import. One can view Plato, with qualification, as an idealist and a rationalist.

Aristotle was one of Plato's students, but placed much more value on knowledge gained from the senses, and would correspondingly better earn the modern label of empiricist. Thus Aristotle set the stage for what would eventually develop into the scientific method centuries later. The works of Aristotle that still exist today appear in treatise form, mostly unpublished by their author. The most important include Physics, Metaphysics, (Nicomachean) Ethics, Politics, De Anima (On the Soul), Poetics, and many others.

Aristotle was a great thinker and philosopher, and was called 'the master' by Avicenna in the following centuries. His views and approaches dominated early Western science for almost 2000 years. As well as philosophy, Aristotle was a formidable inventor, and is credited with many significant inventions and observations. Robert M. Pirsig, the author of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, makes the observation that Aristotle both helped create the analytic approach which forms the backbone of the scientific method and much of philosophy, but that against this, he also took great pride in categorizing nature into lists and taxonomic schemes, which in some cases led to subjects such as rhetoric evolving over time from rich art forms, into recipe-like rules.

Schools of thought in the Hellenistic period

In the Hellenistic period, many different schools of thought developed in the Greek world and often attracted Romans who were responsible for the development of these Greek philosophies. The most notable schools were:

- Neo-Platonism: Ammonius Saccas, Porphyry, Plotinus (Roman), Iamblichus, Proclus

- Academic Skepticism: Arcesilaus, Carneades

- Pyrrhonian Skepticism: Pyrrho, Sextus Empiricus

- Cynicism: Antisthenes, Diogenes of Sinope, Crates of Thebes (taught Zeno of Citium, founder of Stoicism)

- Stoicism: Zeno of Citium, Crates of Mallus (brought Stoicism to Rome c. 170 B.C.E.), Seneca (Roman), Epictetus (Roman), Marcus Aurelius (Roman)

- Epicureanism: Epicurus and Lucretius (Roman)

- Eclecticism: Cicero (Roman)

The spread of Christianity through the Roman world ushered in the end of the Hellenistic philosophy and the beginnings of Medieval Philosophy.

Notes

See also

- Ancient philosophy

- Aristotelianism

- Paideia

- Philosophy

- Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance — a book which inter alia examines the nature of Greek philosophy and its early development.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- John Burnet, Early Greek Philosophy, 1930.

- William Keith Chambers Guthrie, A History of Greek Philosophy: Volume 1, The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans, 1962.

- Martin Litchfield West, Early Greek Philosophy and the Orient, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1971.

- Martin Litchfield West, The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth, Oxford [England] ; New York: Clarendon Press, 1997.

- Charles Freeman (1996). Egypt, Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press.

External links

- The Impact of Greek Culture on Normative Judaism from the Hellenistic Period through the Middle Ages c. 330 B.C.E.- 1250 C.E.

- Greek Philosophy for Kids

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.