Galactose

| Galactose | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | [] |

| PubChem | |

| MeSH | |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | C6H12O6 |

| Molar mass | 180.08 |

| Melting point |

167 degrees C |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) | |

Galactose (Gal) is a six-carbon carbohydrate (a monosaccharide) that is constituent of the disaccharide lactose and found in such sources as agar, sugar beets, and various gums, mucilages, and pectins. As a hexose sugar, galactose has the same formula as glucose, C6H12O6, but differs in the position of the hydroxyl group on carbon-4 (Bender and Bender 2005). Along with glucose and fructose, galactose is one of the three most important blood sugars in animals. Galactose also is known as brain sugar (Houghton Mifflin 1998).

Galactose is less sweet than glucose and sucrose. It is considered a nutritive sweetener because it has food energy. Galactose forms part of glycolipids and glycoproteins in several tissues, and is important in the formation of cerebrosides (galactolipid) of neural tissue (galactocerebrosides).

Description

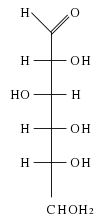

Galactose is a six-carbon monosaccharide. As a carbohydrate, galactose belongs to that class of biological molecules that contain primarily carbon (C) atoms flanked by hydrogen (H) atoms and hydroxyl (OH) groups (H-C-OH). As a hexose carbohydrate, galactose has the same molecular formula as glucose and fructose (C6H12O6) but a different atomic arrangement. It differs from glucose only in the position of the hydroxyl group on carbon-4 (Bender and Bender 2005). (The carbons of glucose are numbered beginning with the more oxidized end of the molecule, the carbonyl group.) In other words, galactose is an epimer of glucose, having a different configuration at only one of several stereogenic centers.

In galactose, the first and last -OH groups point the same way and the second and third -OH groups point the other way.

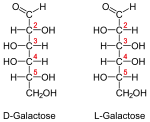

Galactose can be found in two enantiomers, L-galactose and D-galactose. Enantiomers are two stereoisomers that are related to each other by a reflection: They are mirror images of each other. Every stereocenter in one has the opposite configuration in the other. D-Galactose has the same configuration at its penultimate carbon as D-glyceraldehyde.

Galactose is less sweet than glucose and about one-third as sweet as sucrose (Bender and Bender 2005). It also is less soluble in water than glucose.

Sources and relationship to lactose

D-galactose is found in such sources as lactose (milk sugar), agar, gum arabic, sugar beets, seaweed, and nerve cell membranes. L-galactose is found in flaxseed mucilage, snail galactogen, agar, and other such sources. Often the two forms are found together, producing DL-galactose.

Galactose also is synthesized by the body, where it forms part of glycolipids and glycoproteins in several tissues. Galactose is an important component of cerebrosides, which are glycosphingolipids that are important components in animal muscle and nerve cell membranes. Myelin is the most well known cerebroside. Cerebrosides consist of a ceramide with a single sugar residue at the 1-hydroxyl moiety. The sugar residue can be either glucose or galactose; the two major types are therefore called glucocerebrosides and galactocerebrosides. Galactocerebrosides are typically found in neural tissue, while glucocerebrosides are found in other tissues.

Galactan is a polymer of the sugar galactose. It is found in hemicellulose and can be converted to galactose by hydrolysis.

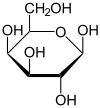

Lactose is a main dietary source of galactose for humans. Lactose is a disaccharide that consists of β-D-galactose and β-D-glucose fragments bonded through a β1-4 glycosidic linkage. The hydrolysis of lactose to glucose and galactose is catalyzed by the enzyme lactase, a β-galactosidase. In the human body, glucose is changed into galactose in order to enable the mammary glands to secrete lactose. The β-galactosidase enzyme is produced by the lac operon in Escherichia coli (E. coli).

Liver galactose metabolism

Galactose in the bloodstream travels to the liver. In the liver, galactose is converted to glucose 6-phosphate in the following reactions:

galacto- uridyl phosphogluco-

kinase transferase mutase

gal --------> gal 1 P ------------------> glc 1 P -----------> glc 6 P

^ \

/ v

UDP-glc UDP-gal

^ /

\___________/

epimerase

Clinical significance

Some studies have suggested a possible link between galactose in milk and ovarian cancer (Cramer 1989; Cramer et al. 1989). Other studies show no correlation, even in the presence of defective galactose metabolism (Goodman et al. 2002; Fung et al. 2003). More recently, pooled analysis done by the Harvard School of Public Health showed no specific correlation between lactose containing foods and ovarian cancer, and showed statistically insignificant increases in risk for consumption of lactose at ≥30 g/d (Genkinger et al. 2006). More research is necessary to ascertain possible risks.

There are some ongoing studies which suggest that galactose may have a role in treatment of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (a kidney disease resulting in kidney failure and proteinuria). This effect is likely to be a result of binding of galactose to FSGS factor.

Metabolic disorders

There are some important disorders involving galactose.

Galactosemia is a rare genetic metabolic disorder which affects an individual's ability to properly metabolize the sugar galactose. Goppert first described the disease in 1917 (Goppert 1917), with its cause as a defect in galactose metabolism being identified by a group led by Herman Kalckar in 1956 (Isselbacher et al. 1956). Its incidence is about 1 per 47,000 births (classic type).

Normally, lactose in food (such as dairy products) is broken down by the body into glucose and galactose, and these sugars are further metabolized. In individuals with galactosemia, the enzymes needed for further metabolism of galactose are severely diminished or missing entirely, leading to toxic levels of galactose to build up in the blood, resulting in hepatomegaly (an enlarged liver), cirrhosis, renal failure, cataracts, and brain damage. Without treatment, mortality in infants with galactosemia is about 75%.

The 4th carbon on Galactose has an axial hydroxyl (-OH) group. This causes galactose to favor the open form as it is more stable than the closed form. This leaves an aldehyde (O=CH-) group available to react with nucleophiles, particularly proteins which contain amino (-NH2) groups, in the body. This uncontrolled reactivity gives way to glycolation. Glycolation causes disease by altering the structure of proteins in ways that were not intended for biochemical processes.

The only treatment for classic galactosemia is eliminating lactose and galactose from the diet. Even with an early diagnosis and a restricted diet, however, some individuals with galactosemia experience long-term complications.

Galactosemia is sometimes confused with lactose intolerance, but galactosemia is a more serious condition. Lactose intolerant individuals have an acquired or inherited shortage of the enzyme lactase, and experience abdominal pains after ingesting dairy products, but no long-term effects. In contrast, a galactosemic individual who consumes galactose can cause permanent damage to their bodies.

Galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase galactosemia (or Galactosemia type 1) is the most common type of galactosemia. It is caused by a deficiency in galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase.

UDPgalactose-4-epimerase deficiency involves the enzyme UDPgalactose-4-epimerase. It is extremely rare, with only 2 reported cases. It causes nerve deafness.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bender, D. A., and A. E. Bender. 2005. A Dictionary of Food and Nutrition. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198609612.

- Houghton Mifflin Company. 1998. Compact American medical dictionary: a concise and up-to-date guide to medical terms. Boston, Mass: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0395884098.

.[7]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Cramer D (1989). Lactase persistence and milk consumption as determinants of ovarian cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol 130 (5): 904-10.

- ↑ Cramer D, Harlow B, Willett W, Welch W, Bell D, Scully R, Ng W, Knapp R (1989). Galactose consumption and metabolism in relation to the risk of ovarian cancer. Lancet 2 (8654): 66-71.

- ↑ Genkinger, Jeanine M., Hunter, David J., Spiegelman, Donna, Anderson, Kristin E., Arslan, Alan, Beeson, W. Lawrence, Buring, Julie E., Fraser, Gary E., Freudenheim, Jo L., Goldbohm, R. Alexandra, Hankinson, Susan E., Jacobs, David R., Jr., Koushik, Anita, Lacey, James V., Jr., Larsson, Susanna C., Leitzmann, Michael, McCullough, Marji L., Miller, Anthony B., Rodriguez, Carmen, Rohan, Thomas E., Schouten, Leo J., Shore, Roy, Smit, Ellen, Wolk, Alicja, Zhang, Shumin M., Smith-Warner, Stephanie A. (2006). Dairy Products and Ovarian Cancer: A Pooled Analysis of 12 Cohort Studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15: 364-372.

- ↑ Marc T. Goodman , Anna H. Wu , Ko-Hui Tung , Katharine McDuffie , Daniel W. Cramer , Lynne R. Wilkens , Keith Terada , Juergen K. V. Reichardt , and Won G. Ng (2002). Association of Galactose-1-Phosphate Uridyltransferase Activity and N314D Genotype with the Risk of Ovarian Cancer. Am. J. Epidemiol 156 (8): 693-701.

- ↑ Fung, W. L. Alan, Risch, Harvey, McLaughlin, John, Rosen, Barry, Cole, David, Vesprini, Danny, Narod, Steven A. (2003). The N314D Polymorphism of Galactose-1-Phosphate Uridyl Transferase Does Not Modify the Risk of Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 12 (7): 678-80.

- ↑ Goppert F. Galaktosurie nach Milchzuckergabe bei angeborenem, familiaerem chronischem Leberleiden. Klin Wschr 1917;54:473-477.

- ↑ Isselbacher KJ, Anderson EP, Kurahashi K, Kalckar HM (1956). Congenital galactosemia, a single enzymatic block in galactose metabolism. Science 13 (123): 635-6.