|

|

| (30 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] |

| | [[Category:Anthropology]] | | [[Category:Anthropology]] |

| − | {{Started}}{{Claimed}} | + | [[Category:Mythical creatures]] |

| − | | + | {{Ebapproved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} |

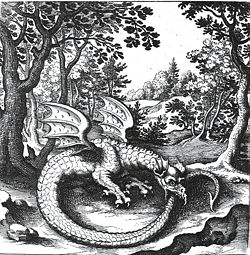

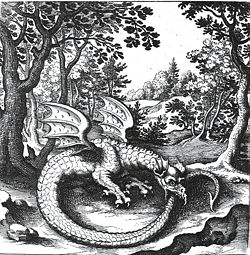

| | + | [[Image:Ouroboros_1.jpg|thumb|right|250px| Engraving of Ouroboros (a dragon swallowing its own tail) by Lucas Jennis, in alchemical tract titled ''De Lapide Philisophico''.]] |

| | | | |

| | :''This article focuses on European dragons.'' | | :''This article focuses on European dragons.'' |

| − | :''for dragons in Oriental cultures see [[Chinese dragon]]'' | + | :''For dragons in Oriental cultures see [[Chinese dragon]]'' |

| − | [[Image:Ljubljana dragon.JPG|thumb|300 px| Statue of dragon, Ljubljana, Slovenia]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | The '''dragon''' is a mythical creature typically depicted as a large and powerful [[Serpent (symbolism)|serpent]] or other [[reptile]] with [[magical]] or [[Spirituality|spiritual]] qualities. Mythological creatures possessing some or most of the characteristics typically associated with dragons are common throughout the world's cultures.<ref name=Jones>{{cite book|last=Jones|first=David|title=An Instinct for Dragons|publisher=Routlege|year=2002}}</ref> It is well known that there is a negative image in the western world of the dragon, but in East Asia, especially in China, the dragon has a positive image and is a benevolent god.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Overview==

| |

| − | [[Image:Ouroboros_1.jpg|thumb|right|300px| Engraving of [[Ouroboros]] (a dragon swallowing its own tail) by [[Lucas Jennis]], in [[alchemical]] tract titled ''[[De Lapide Philisophico]]''.]]

| |

| − | Dragons are commonly portrayed as serpentine or reptilian, hatching from [[egg]]s and possessing extremely large, typically scaly, bodies; they are sometimes portrayed as having large eyes, a feature that is the origin for the word for dragon in many cultures, and are often (but not always) portrayed with wings and a fiery breath. Some dragons do not have wings at all, but look more like long snakes. Dragons can have a variable number of legs: none, two, four, or more when it comes to early European literature. Modern depictions of dragons are very large in size, but some early European depictions of dragons were only the size of bears, or, in some cases, even smaller, around the size of a butterfly.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Although dragons (or dragon-like creatures) occur commonly in legends around the world, different cultures have perceived them differently. [[Chinese dragon]]s ({{zh-stp|t=龍|s=龙|p=lóng}}), and Eastern dragons generally, are usually seen as benevolent, whereas [[Dragon#European dragons|European dragon]]s are usually malevolent (there are of course exceptions to these rules). Malevolent dragons also occur in [[Persian mythology]] (see [[Zahhak|Azhi Dahaka]]) and other cultures.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Dragons are particularly popular in China. Along with the [[phoenix (mythology)|phoenix]], the dragon was a symbol of the Chinese emperors. Dragon costumes manipulated by several people are a common sight at Chinese festivals.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Dragons are often held to have major spiritual significance in various religions and cultures around the world. In many [[Eastern]] and [[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|Native American]] cultures dragons were, and in some cultures still are, revered as representative of the primal forces of [[nature]] and the [[universe]]. They are associated with [[wisdom]]—often said to be wiser than humans—and longevity. They are commonly said to possess some form of [[Magic (paranormal)|magic]] or other supernormal power, and are often associated with wells, rain, and rivers. In some cultures, they are said to be capable of human speech. They are also said to be able to talk to all animals and converse with humans.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Dragons are very popular characters in [[fantasy literature]], [[role-playing games]] and [[video games]] today.

| |

| − | | |

| − | The term ''[[dragoon]]'', for infantry that move around by [[horse]] yet still fight as foot soldiers, is derived from their early [[firearm]], the "dragon", a wide-bore musket that spat flame when it fired, and was thus named for the mythical beast.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | [[Image:Zmey.jpg|thumb|right|''[[Dobrynya Nikitich]] slaying [[Zmey Gorynych]]'', by [[Ivan Bilibin]]]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Symbolism==

| |

| − | In [[Middle Ages|medieval]] symbolism, dragons were often symbolic of [[apostasy]] and treachery, but also of anger and envy, and eventually symbolized great calamity. Several heads were symbolic of decadence and oppression, and also of [[heresy]]. They also served as symbols for independence, leadership and strength. Many dragons also represent wisdom; slaying a dragon not only gave access to its treasure hoard, but meant the hero had bested the most cunning of all creatures. In some cultures, especially Chinese, or around the Himalayas, dragons are considered to represent good luck.

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Joseph Campbell]] in the ''[[The Power of Myth]]'' viewed the dragon as a symbol of divinity or transcendence because it represents the unity of Heaven and Earth by combining the serpent form (earthbound) with the bat/bird form (airborne).

| |

| − | | |

| − | Dragons embody both male and female traits as in the example from Aboriginal myth that raises baby humans to adulthood training them for survival in the world (Littleton, 2002, p. 646). Another contrast in the way dragons are portrayed is their ability to breathe fire but live in the ocean—water and fire together. And like in the quote from Joseph Campbell above, they also include the opposing elements of earth and sky. Dragons represent the joining of the opposing forces of the [[cosmos]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | Yet another symbolic view of dragons is the [[Ouroborus]], or the dragon encircling and eating its own tail. When shaped like this the dragon becomes a symbol of eternity, natural cycles, and completion.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===In Christianity===

| |

| − | The Latin word for a dragon, ''draco'' ([[genitive]]: ''draconis''), actually means ''snake'' or ''serpent'', emphasizing the European association of dragons with snakes. The Medieval Biblical interpretation of the [[Devil]] being associated with the serpent who tempted Adam and Eve, thus gave a snake-like dragon connotations of evil. Generally speaking, Biblical literature itself did not portray this association (save for the [[Book of Revelation]], whose treatment of dragons is detailed below). The demonic opponents of God, Christ, or good Christians have commonly been portrayed as reptilian or chimeric.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In the [[Book of Job]] Chapter 41, the sea monster [[Leviathan]], which has some dragon-like characteristics.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In [[Book of Revelation|Revelation 12:3]], an enormous red beast with seven heads is described, whose tail sweeps one third of the stars from heaven down to earth (held to be symbolic of the fall of the angels, though not commonly held among biblical scholars). In most translations, the word "dragon" is used to describe the beast, since in the original [[Greek language|Greek]] the word used is drakon (δράκον).

| |

| − | | |

| − | In [[iconography]], some Catholic [[saint]]s are depicted in the act of killing a dragon. This is one of the common aspects of [[Saint George]] in [[Egyptian language|Egyptian]] [[Copt|Coptic]] iconography [http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/stgeorge.htm], on the [[coat of arms of Moscow]], and in [[England|English]] and [[Principality of Catalonia|Catalan]] legend. In Italy, [[Saint Mercurialis]], first bishop of the city of [[Forlì]], is also depicted slaying a dragon.[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06137a.htm] [[Saint Julian of Le Mans]], [[Saint Veran]], [[Saint Crescentinus]], and [[Saint Leonard of Noblac]] were also venerated as dragon-slayers.

| |

| − | | |

| − | However, some say that dragons were good, before they fell, as humans did. Also contributing to the good dragon argument in Christianity is the fact that, if they did exist, they were created as were any other creature, as seen in [[Dragons In Our Midst]], a contemporary Christian book series by author Bryan Davis.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Chinese zodiac===

| |

| − | The years 1916, 1928, 1940, 1952, 1964, 1976, 1988, 2000, 2012, 2024, 2036, 2048, 2060 are considered the Year of the Dragon in the [[Chinese zodiac]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | The Chinese zodiac purports that people born in the Year of the Dragon are healthy, energetic, excitable, short-tempered, and stubborn. They are also supposedly honest, sensitive, brave, and inspire confidence and trust. The Chinese zodiac purports that Dragon people are the most eccentric of any in the eastern zodiac. They supposedly neither borrow money nor make flowery speeches, but tend to be soft-hearted which sometimes gives others an advantage over them. They are purported to be compatible with [[Rat (Zodiac)|Rats]], [[Snake (Zodiac)|Snakes]], [[Monkey (Zodiac)|Monkeys]], and [[Rooster (Zodiac)|Roosters]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===In East Asia===

| |

| − | {{main|Chinese dragon}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | Dragons are commonly symbols of good luck or health in some parts of Asia, and are also sometimes worshipped. Asian dragons are considered as mythical rulers of weather, specifically rain and water, and are usually depicted as the guardians of flaming pearls.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In [[China]], as well as in [[Japan]] and [[Korea]], the [[Azure Dragon (Chinese constellation)|Azure Dragon]] is one of the [[Four Symbols (Chinese constellation)|Four Symbols]] of the [[Chinese constellation]], representing [[spring (season)]], the element of [[Wood]] and the [[east]]. Chinese dragons are often shown with large pearls in their grasp, though some say that it is really the dragon's egg. The Chinese believed that the dragons lived under water most of the time, and would sometimes offer rice as a gift to the dragons. The dragons were not shown with wings like the European dragons because it was believed they could fly using magic.

| |

| − | | |

| − | A ''Yellow dragon'' (Huang long) with five claws on each foot, on the other hand, represents the change of seasons, the element of [[Earth_(classical_element)|Earth]] (the Chinese 'fifth element') and the center. Furthermore, it symbolizes imperial authority in [[China]], and indirectly the [[Han Chinese|Chinese people]] as well. Chinese people often use the term "''Descendants of the Dragon''" as a sign of ethnic identity. The dragon is also the symbol of royalty in [[Bhutan]] (whose sovereign is known as [[Druk Gyalpo]], or Dragon King).

| |

| − | | |

| − | In [[Vietnam]], the '''dragon''' ([[Vietnamese]]: rồng) is the most important and sacred symbol. According to the ancient [[creation myth]] of the [[Kinh]] people, all Vietnamese people are descended from dragons through [[Lac Long Quan|Lạc Long Quân]], who married [[Au Co|Âu Cơ]], a fairy. The eldest of their 100 sons founded the first dynasty of [[Hùng Vương]] Emperors.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==History and origins of dragons==

| |

| − | {{Unreferencedsect|date=June 2006}}{{cleanup-date|November 2006}}

| |

| − | [[Image:Laonaga.JPG|thumb|300px|A [[naga (mythology)|naga]] guarding the Temple of [[Wat Sisaket]] in [[Vientiane|Viang Chan]], Laos]]

| |

| − | Where the original concept of a dragon came from is unknown, as there is no accepted scientific theory or any evidence to support that dragons actually exist or have existed.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Some believe that the dragon may have had a real-life counterpart from which the legends around the world arose — typically [[dinosaurs]] or other [[archosaurs]] are mentioned as a possibility — but there is no physical evidence to support this claim, only alleged sightings collected by [[cryptozoology|cryptozoologists]]. In a common variation of this hypothesis, giant lizards such as [[Megalania]] are substituted for the [[living dinosaurs]]. Some [[Creationism|Creationists]] hold that dragons are just an exaggerated depiction of what we now call dinosaurs and that humans and dinosaurs (dragons) did co-exist.<ref>Rouster, Lourella. (1997). ''The Footprints of Dragons''. http://www.rae.org/dragons.html</ref> All of these hypotheses are widely considered to be [[pseudoscience]] or myth.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Dinosaur fossils were once thought of as "dragon bones" — a discovery in 300 B.C.E. in [[Wucheng]], [[Sichuan]], [[China]], was labeled as such by [[Chang Qu]].<ref>http://www.abc.net.au/science/k2/moments/s1334145.htm</ref> It is unlikely, however, that these finds alone prompted the legends of flying monsters, but may have served to reinforce them.

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Herodotus]], often called the "father of history", visited Judea c.450 B.C.E. and wrote that he heard of caged dragons in nearby Arabia, near [[Petra, Jordan]]. Curious, he travelled to the area and found many skeletal remains of serpents and mentioned reports of flying serpents flying from Arabia into [[Egypt]] but being fought off by [[Ibis|Ibises]] {{cite web | title=Histories | work=Histories (Greek) | url=http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0125&layout=&loc=2.75.1 | accessdate=2006-06-14}}.

| |

| − | | |

| − | According to [[Marco Polo]]'s journals, Polo was walking through Anatolia into Persia and came upon real live flying dragons that attacked his party caravan in the desert and he reported that they were very frightening beasts that almost killed him in an attack.{{citation needed}} Polo did not write his journals down — they were dictated to his cellmate in prison, and there is much dispute over whether this writer may have invented the dragon to embellish the tale.{{citation needed}} Polo was also the first western man to describe Chinese "dragon bones" with early writing on them. These bones were presumably either fossils (as described by Chang Qu) or the bones of other animals.{{citation needed}} Reference: [[Il Milione]]

| |

| | | | |

| − | It has also been suggested by proponents of [[catastrophism]] that [[comet]]s or [[meteor]] showers gave rise to legends about fiery serpents in the sky.{{Citation needed}} In Old English, comets were sometimes called fyrene dracan or fiery dragons. Volcanic eruptions may have also been responsible for reinforcing the belief in dragons, although instances in Europe and asian countries were rare.

| + | The '''dragon''' is a [[mythical creature]] typically depicted as a large and powerful [[Serpent (symbolism)|serpent]] or other [[reptile]] with [[magic]]al or [[Spirituality|spiritual]] qualities. Although dragons (or dragon-like creatures) occur commonly in [[legend]]s around the world, different [[culture]]s have perceived them differently. [[Chinese dragon]]s, and Eastern dragons generally, are usually seen as benevolent and spiritual, representative of primal forces of nature and the universe, and great sources of wisdom. In contrast, [[Europe|European]] dragons, as well as some cultures of [[Asia Minor]] such as the [[ancient Persian Empire]], were more often than not malevolent, associated with [[evil]] supernatural forces and the natural enemy of humanity. The most notable exception is the [[Ouroborus]], or the dragon encircling and eating its own tail. When shaped like this the dragon becomes a [[symbol]] of [[eternity]], natural cycles, and completion. Dragons are commonly said to possess some form of magic or other supernormal powers, the most famous being the ability to breathe [[fire]] from their mouths. |

| | + | {{toc}} |

| | + | Over the years dragons have become the most famous and recognizable of all mythical creatures, used repeatedly in fantasy, [[fairy tale]]s, video-games, film, and role-playing games of pop culture fame. While still seen as powerful and often dangerous to humankind, the latter part of the twentieth century saw a change in attitude, with the good qualities of dragons becoming more prominent. No longer must all dragons be defeated by the [[hero]] or [[saint]], some are ready to share their wisdom with human beings and act as companions, friends, and even guardians of children—roles that parallel those of the [[angel]]s. |

| | | | |

| − | In [[Hindu mythology]], [[Manasa]] and [[Vasuki]] are serpent like creatures associated with the dragon. [http://www.firstage.net/articles/famous_dragon_names.html] [[Indra]], is the hindu storm god who slays [[Vritra]], a large serpent like creature on a mountain.

| + | ==Etymology== |

| | + | The word "dragon" has [[etymology|etymological]] roots as far back as [[Ancient Greek Language|ancient Greek]], in the verb meaning "to see strong." There were several similar words in contemporary languages of the time that described some form of clear sight, but at some point, the Greek verb was fused with the word for [[serpent]], ''drakon'' (δράκον). From there it worked its way to the [[Latin language]], where it was called ''Draconis,'' meaning "snake" or "serpent." In the [[English language]], the Latin word was split into several different words, all similar: Dragon became the official name for the large, [[mythical creature]]s, while variations on the root, such as "draconian," "draconic," and "draconical" all came to be adjectives describing something old, rigid, out of touch with the world, or even evil.<ref> ''The Oxford English Dictionary'' (Oxford University Press, 1971) </ref> |

| | | | |

| − | The Vietnamese dragon is the combined image of crocodile, snake, lizard and bird. Historically, Vietnamese people lived near rivers, so they venerated crocodiles as "Giao Long", the first kind of Vietnamese dragon. Then, many kinds of dragon were developed in architecture, painting, literature and Vietnamese consciousness.

| + | ==Description== |

| | | | |

| − | In [[Greek mythology]] there are many snake or dragon legends, usually in which a serpent or dragon guards some treasure. The first [[Pelasgian]] kings of Athens were said to be half human, half snake. The dragon [[Ladon]] guarded the Golden Apples of the Sun of the [[Hesperides]]. Another serpentine dragon guarded the [[Golden Fleece]], protecting it from theft by [[Jason]] and the [[Argonauts]]. Similarly, [[Pythia]] and [[Python (mythology)|Python]], a pair of serpents, guarded the temple of [[Gaia (mythology)|Gaia]] and the Oracular priestess, before the [[Delphic Oracle]] was seized by [[Apollo]] and the two serpents were draped around his winged [[caduceus]], which he then gave to [[Hermes]].

| + | Dragons generally fit into two categories in [[Europe]]an lore: The first has large wings that enable the creature to fly, and it breathes [[fire]] from its mouth. The other corresponds more to the image of a giant [[snake]], with no wings but a long, cylindrical body that enables it to slither on the ground. Both of these types are commonly portrayed as [[reptile|reptilian]], hatching from [[egg]]s, with scaly bodies, and occasionally large eyes. Modern depictions of dragons are very large in size, but some early European depictions of dragons were only the size of [[bear]]s, or, in some cases, even smaller, around the size of a [[butterfly]]. Some dragons were personified to the point that they could speak and felt [[emotion]]s, while others were merely feral beasts. |

| | | | |

| − | The Greek myths of Hercules and Ladon and others are believed to be based upon earlier from [[Canaan]]ite myth where [[Baal]] overcame [[Lotan]], and [[Israel]]ite [[Yahweh]] overcame [[Leviathan]]. These stories too go back still further in history 1,500 B.C.E., to the [[Hittite]] or [[Hurrian]] hero [[Kumarbi]] who had to overcome the dragon [[Illuyankas]] of the Sea.

| + | ==Origins== |

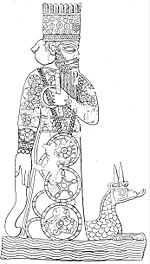

| | + | [[Image:Marduk and pet.jpg|thumb|right|150 px|The ancient [[Mesopotamia]]n god [[Marduk]] and his dragon, from a [[Babylonia]]n cylinder seal]] |

| | + | Scholars have attempted to uncover the true source of dragon [[legend]]s since reports of the ancient creatures themselves have been made public. While it is most probable that dragons in the form popular today never did exist, there is evidence to suggest that perhaps the belief in dragons was based on something real. Some have looked to [[dinosaur]]s as the answer. |

| | | | |

| − | In Australian Aboriginal mythology, the [[Rainbow Serpent]] was a culture hero in many parts of the country. Known by different names in different places, from the [[Waugal]] of the South Western [[Nyungar]], to the Ganba of the North Central Deserts or the Wanambee of South Australia, the rainbow serpent, associated with the creation of waterholes and river courses, was to be feared and respected.

| + | It is known that ancient cultures, such as the Greeks and [[Ancient China|Chinese]] found [[fossil]] remains of large creatures they could not easily identify. Such fossils have been held responsible for the creation of other [[mythical creature]]s, so it is possible that the belief in dragons could have been fostered in the remains of real animals. |

| | | | |

| − | Recently, the [[Discovery Channel]] ran a programme titled ''[[Dragons: A Fantasy Made Real]]''. The programme tries to look at plausible scientific explanations to assume a "what if" scenario, putting various theories and portraying dragons as if they had existed.[http://animal.discovery.com/convergence/dragons/dragons.html]

| + | Some take this hypothesis a step further and suggest that dragons are actually a distant memory of real dinosaurs passed down through the generations of humanity. This belief explains why dragons appear in nearly every culture, as well as why the dragon is more closely recognizable as a dinosaur than any other animal.<ref>Lourella Rouster, [http://www.rae.org/dragons.html "The Footprints of Dragons"] (1997). Retrieved April 14, 2007</ref> However, such theories disregard the accepted timeline of the [[Earth]]'s history, with [[human being]]s and dinosaurs separated by sixty-five million years, and therefore are disregarded by mainstream scholars. It is more likely that a lack of understanding of nature, certain fossils, a stronger connection with the supernatural, and even perhaps a widespread fear of [[snake]]s and reptiles all helped form the idea of the dragon. |

| | + | [[Image:Cadmus teeth.jpg|thumb|left|200px|''Cadmus Sowing the Dragon's teeth,'' by Maxfield Parrish, 1908]] |

| | + | Some of the earliest references to dragons in the west come from [[Greece]]. [[Herodotus]], often called the "father of history," visited [[Judea]] c.450 B.C.E. and wrote that he heard of dragons, described as small, flying [[reptile]]-like creatures. He also wrote that he observed the bones of a large, dragon creature.<ref> Michon Scott, [http://www.strangescience.net/herodotus.htm "Herodotus"] (2005). Retrieved April 14, 2007. </ref> |

| | + | The idea of dragons was not unique to Herodotus in [[Greek mythology]]. There are many snake or dragon legends, usually in which a serpent or dragon guards some treasure. |

| | | | |

| − | ==European dragons==

| + | The first [[Pelasgian]] kings of [[Athens]] were said to be half human, half snake. [[Cadmus]] slew the water-dragon guardian of the Castalian Spring, and on the instructions of [[Athena]], he sowed the dragon's teeth in the ground, from which there sprang a race of fierce armed men, called Spartes ("sown"), who assisted him to build the citadel of [[Thebes]], becoming the founders of the noblest families of that city. The dragon Ladon guarded the Golden Apples of the Sun of the [[Hesperides]]. Another serpentine dragon guarded the [[Golden Fleece]], protecting it from theft by [[Jason]] and the [[Argonauts]]. Similarly, [[Pythia]] and [[Python (mythology)|Python]], a pair of serpents, guarded the temple of [[Gaia]] and the Oracular priestess, before the [[Delphic Oracle]] was seized by [[Apollo]] and the two serpents were draped around his winged caduceus, which he then gave to [[Hermes]].<ref> Edith Hamilton, ''Mythology'' (New York, NY: Little Brown and Company 1942) </ref> These stories are not the first to mention dragon-like creatures, but perhaps mark the time in which dragons become popular in Western beliefs, since European culture was so heavily influenced by ancient Greece. |

| − | In [[European]] [[folklore]], a '''[[dragon]]''' is a [[Serpent (symbolism)|serpentine]] [[legendary creature]]. The Latin word ''draco,'' as in the [[Draco (constellation)|constellation Draco]], comes directly from [[Ancient Greek|Greek]] ''δράκων'', drákōn. The word for dragon in [[Germanic mythology]] and its descendants is ''[[wiktionary:worm|worm]]'' ([[Old English language|Old English]]: ''wyrm'', [[Old High German]]: ''wurm'', [[Old Norse language|Old Norse]]: ''ormr''), meaning snake or serpent. In Old English ''wyrm'' means "serpent", ''draca'' means "dragon". Finnish ''lohikäärme'' means directly "salmon-snake", but the word ''lohi-'' was originally ''louhi-'' meaning crags or rocks, a "mountain snake". Though a winged creature, the dragon is generally to be found in its underground [[lair]], a cave that identifies it as an ancient creature of earth. Likely, the dragons of European and Mid Eastern mythology stem from the cult of snakes found in religions throughout the world.

| |

| | | | |

| − | The dragon of the modern period is typically depicted as a huge fire-breathing, scaly and horned [[dinosaur]]-like creature, with leathery wings, with four legs and a long muscular tail. It is sometimes shown with feathered wings, crests, fiery manes, and various exotic colorations. Iconically it has at last combined the [[Chinese dragon]] with the western one. Asian dragons are long serpent like creatures which possess the scales of a carp, horns of a deer, feet of an eagle, the body of a snake, a feathery mane, large eyes, and can be holding a pearl to control lightning. They usually have no wings. Imperial dragons that were sewn on to silk had five claws (for a king), or four for a prince, or three for courtiers of a lower ranking. The dragons were bringers of rain and lived in and governed bodies of water (e.g lakes, rivers, oceans, or seas). Asian dragons were benevolent, but bossy (this strict behavior is why one of China's nicknames is "the Dragon"). In Western folklore, dragons are usually portrayed as [[evil]], with exceptions mainly in modern fiction.

| + | In [[Middle Ages|medieval]] symbolism, dragons were often symbolic of [[apostasy]] and treachery, but also of anger and envy, and eventually symbolized great calamity. Several heads were symbolic of decadence and oppression, and also of [[heresy]]. They also served as symbols for independence, leadership, and strength. Many dragons also represent wisdom; slaying a dragon not only gave access to its treasure hoard, but meant the hero had bested the most cunning of all creatures. [[Joseph Campbell]] in the ''The Power of Myth'' viewed the dragon as a symbol of [[divinity]] or transcendence, because it represents the unity of Heaven and Earth by combining the serpent form (earthbound) with the bat/bird form (airborne). |

| | | | |

| − | Many modern stories represent dragons as extremely [[intelligence (trait)|intelligent]] creatures who can talk, associated with (and sometimes in control of) powerful [[magic (paranormal)|magic]]. Dragon's blood often has magical properties: for example it let [[Siegfried (opera)|Siegfried]] understand the language of the Forest Bird. The typical dragon protects a cavern or castle filled with [[gold]] and [[treasure]] and is often associated with a great hero who tries to slay it, but dragons can be written into a story in as many ways as a human character. This includes the monster being used as a wise being whom heroes could approach for help and advice.

| + | ==European Mythology== |

| | | | |

| − | <!--Drakes are of dragonkin, their shape is more lithe than of normal dragon's. Drakes vary in size but are usually smaller than dragons and other wyrmkin.<1—Any source for this, or is it anime or video games?—>

| + | While there are many similarities between dragons throughout Europe, there were many distinctions from culture to culture. The following are some examples of variations on the dragon. |

| | | | |

| − | === Roman dragons === | + | ===Slavic mythology=== |

| − | Roman dragons evolved from serpentine Greek ones, combined with the dragons of the [[Near East]], in the mix that characterized the hybrid Greek/Eastern [[Hellenistic]] culture. From Babylon, the [[Sirrush|musrussu]] was a classic representation of a Near Eastern dragon. John's ''[[Book of Revelation]]'' — Greek literature, not Roman — describes Satan as "a great dragon, flaming red, with seven heads and ten horns". Much of John's literary inspiration is late Hebrew and Greek, but John's dragon, like his [[Satan]], are both more likely to have come originally through the Near East. Perhaps the distinctions between dragons of western origin and Chinese dragons (''q.v.'') are arbitrary. A later Roman dragon was certainly of Iranian origin: in the Roman Empire, where each military cohort had a particular identifying ''signum'', (military standard), after the [[Dacian Wars]] and [[Parthian Wars|Parthian War]] of Trajan in the east, the Draco military standard entered the Legion with the Cohors Sarmatarum and Cohors Dacorum ([[Sarmatian]] and [[Dacian]] [[cohort]]) — a large dragon fixed to the end of a lance, with large gaping jaws of silver and with the rest of the body formed of colored silk. With the jaws facing into the wind, the silken body inflated and rippled, resembling a [[windsock]]. This signum is described in Vegetius ''Epitoma Rei Militaris,'' 379 C.E. (book ii, ch XIII. 'De centuriis atque vexillis peditum'):

| + | [[Image:Zmey_Gorynych.jpg|thumb|200 px|right|Zmey Gorynych, by Victor Vasnetsov]] |

| | + | Dragons of [[Slavic mythology]], known as ''zmeys'' (Russian), ''smok'' (Belarussian), ''zmiy'' (Ukrainian), are generally seen as protectors of crops and fertility. They tend to be three headed, conglomerates of [[snake]]s, [[human]]s, and [[bird]]s, they are never bound to one form and often shape shift. They are however, often portrayed as male, and seen as sexually aggressive, often mating with humans. They are associated with [[fire]] and [[water]], as both are crucial for human survival.<ref> A Spell In Time (2000) [http://www.spellintime.fsnet.co.uk/Folklore_Section_Tales.htm "Bulgarian Traditional Tales"] Retrieved April 18, 2007 </ref> |

| | | | |

| − | === Dragons in Slavic mythology ===

| + | Occasionally, a similar creature is seen as an evil, four-legged beast with few, if any, redeeming qualities. They are intelligent, but not very highly so; they often place tribute on villages or small towns, demanding [[maiden]]s for food, or [[gold]]. Their number of heads ranges from one to seven or sometimes even more, with three- and seven-headed dragons being most common. The heads also regrow if cut off, unless the neck is "treated" with fire (similar to the [[hydra]] in [[Greek mythology]]). Dragon [[blood]] is so [[poison]]ous that the earth itself will refuse to absorb it. |

| − | [[Image:Zmey_Gorynych.jpg|thumb|right|Zmey Gorynych, by Victor Vasnetsov]] | + | [[Image:Ljubljana dragon.JPG|left|thumb|250 px| Statue of dragon, Ljubljana, Slovenia]] |

| | + | The most famous [[Poland|Polish]] dragon is the Wawel Dragon or ''smok wawelski.'' It supposedly terrorized ancient [[Kraków]] and lived in caves on the [[Vistula]] river bank below the [[Wawel]] castle. According to lore based on the ''[[Book of Daniel]],'' it was killed by a boy who offered it a [[sheep]]skin filled with [[sulfur]] and [[tar]]. After devouring it, the dragon became so thirsty that it finally exploded after drinking too much water. A metal sculpture of the Wawel Dragon is a well-known tourist sight in Kraków. It is very stylized but, to the amusement of children, noisily breathes [[fire]] every few minutes. Other dragon-like creatures in Polish folklore include the [[basilisk]], living in cellars of [[Warsaw]], and the [[Snake King]] from folk legends. |

| | | | |

| − | Dragons of [[Slavic mythology]] hold mixed temperaments towards humans. For example, dragons (дракон, змей, ламя) in [[Bulgarians|Bulgarian]] mythology are either [[male]] or [[female]], each gender having a different view of mankind. The female dragon and male dragon, often seen as brother and sister, represent different forces of [[agriculture]]. The female dragon represents harsh weather and is the destroyer of crops, the hater of mankind, and is locked in a never ending battle with her brother. The male dragon protects the humans' crops from destruction and is generally loving to humanity. [[Fire]] and [[water]] play major roles in Bulgarian dragon lore; the female has water characteristics, whilst the male is usually a fiery creature.

| + | However, the Slavic dragon is not always harmful to man. The best example of this is the [[Slovenia]]n dragon of [[Ljubljana]], who benevolently protects the city of Ljubljana and is pictured in the city's coat of arms. |

| − | In Bulgarian legend, dragons are three headed, winged beings with [[snake]]'s bodies.

| |

| | | | |

| − | In [[Russians|Russian]], [[Belarusians|Belarusian]], and [[Ukrainians|Ukrainian]] lore, a dragon, or ''[[zmey]]'' (Russian), ''smok'' (Belarussian) ''zmiy'' (Ukrainian), is generally an evil, four-legged beast with few if any redeeming qualities. ''Zmeys'' are intelligent, but not very highly so; they often place tribute on villages or small towns, demanding [[maiden]]s for food, or [[gold]]. Their number of heads ranges from one to seven or sometimes even more, with three- and seven-headed dragons being most common. The heads also regrow if cut off, unless the neck is "treated" with fire (similar to the hydra in Greek mythology). [[Dragon blood]] is so poisonous that Earth itself will refuse to absorb it.

| + | ===Germanic and Norse mythology=== |

| | + | [[Image:Ring45.jpg|thumb|right|200 px| Having slain Fafner, Siegfried tastes his blood and comes to understand the speech of birds.]] |

| | | | |

| − | The most famous [[Poland|Polish]] dragon is the [[Wawel Dragon]] or ''smok wawelski''. It supposedly terrorized ancient [[Kraków]] and lived in caves on the [[Vistula]] river bank below the [[Wawel]] castle. According to lore based on the ''[[Book of Daniel]]'', it was killed by a boy who offered it a [[Sheepskin (material)|sheepskin]] filled with sulphur and tar. After devouring it, the dragon became so thirsty that it finally exploded after drinking too much water. A metal sculpture of the Wawel Dragon is a well-known tourist sight in Kraków. It is very stylised but, to the amusement of children, noisily breathes fire every few minutes. The Wawel dragon also features on many items of Kraków tourist merchandise.

| + | In [[Germanic mythology|Germanic]] and [[Norse mythology|Norse]] traditions, dragons were often depicted as a "Lindworm," a variation on the [[serpent]]ine creatures known as the ''[[wyvern]].'' They usually appeared as monstrous serpents, sometimes with wings and legs, but more often as gigantic snake-like creatures than traditional dragons. The lindworms were seen as [[evil]], a bad [[omen]], and were often blamed for preying on [[cattle]] and other livestock. They were particularly greedy creatures, guarding hordes of treasure and most often living in underground [[cave]]s. Often in Germanic and Norse stories lindworms are actually people whose own greed have led to their transformation into a creature that resembles their sins, the legends of [[Jormugand]], who ate so much he grew to be proportional to the length of the [[Earth]], and [[Fafnir]], the human who killed his own father to inherit his wealth and became a dragon to protect his treasure, being the most famous.<ref> Kylie McCormick, [http://www.blackdrago.com/famous_norse.htm#top "Norse, Scandinavian and Germanic Dragons"] (2006) Retrieved April 15, 2007 </ref> |

| | | | |

| − | Other dragon-like creatures in Polish folklore include the [[basilisk]], living in cellars of [[Warsaw]], and the Snake King from folk legends.

| + | ===British Mythology=== |

| | + | [[Image:stgeorge-dragon.jpg|left|200 px|thumb|Saint George versus the dragon]] |

| | | | |

| − | === Dragons in Germanic mythology ===

| + | Dragons have long been present in [[Great Britain|British]] lore. More often than not dragons were similar to the ''wyverns'' of central [[Europe]], however there were also large, flying dragons that breathed [[fire]]. The most famous dragon in [[England]] is perhaps the one slain by the country's [[patron]] [[Saint George]]. |

| − | [[Image:Ring45.jpg|thumb|left|200 px| Having slain Fafner, Siegfried tastes his blood and comes to understand the speech of birds.]] | |

| − | The most famous dragons in [[Norse mythology]] and [[Germanic mythology]], are:

| |

| − | *[[Níðhöggr]] who gnawed at the roots of [[Yggdrasil]];

| |

| − | * The dragon encountered by [[Beowulf (character)|Beowulf]];

| |

| − | * [[Fafnir]], who was killed by [[Sigurd|Siegfried]]. Fafnir turned into a dragon because of his greed.

| |

| − | * [[Lindworm]]s are monstrous serpents of Germanic myth and lore, often interchangeable with dragons.

| |

| | | | |

| − | Many European stories of dragons have them guarding a treasure hoard. Both Fafnir and Beowulf's dragon guarded earthen mounds full of ancient treasure. The treasure was cursed and brought ill to those who later possessed it.

| + | Today, there are two distinct dragons in the British Isles. The White dragon, which symbolizes England, and the Red dragon that appears on the [[Wales|Welsh]] flag, known as ''(Y Ddraig Goch)''. An ancient story in Britain tells of a white dragon and a red dragon fighting to the death, with the red dragon being the resounding victor. The red dragon is linked with the [[Brython|Britons]] who are today represented by the Welsh and it is believed that the white dragon refers to the [[Saxons]] - now the [[England|English]] - who invaded southern [[Britain]] in the fifth and sixth centuries. Some have speculated that it originates from [[Arthurian Legend]] where [[Merlin (wizard)|Merlin]] had a vision of the red dragon (representing [[Vortigern]]) and the white dragon (representing the invading Saxons) in battle. That particular legend also features in the [[Mabinogion]] in the story of ''Llud and Llevelys''. |

| | | | |

| − | Dragons in the emblem books popular from late medieval times through the 17th century often represent the dragon as an emblem of greed. (''Some quotes are needed'') The prevalence of dragons in European [[heraldry]] demonstrates that there is more to the dragon than greed.

| + | ===Basque mythology=== |

| | | | |

| − | Though the Latin is ''draco, draconis'', it has been supposed by some scholars, including [[John Tanke]] of the [[University of Michigan]], that the word ''dragon'' comes from the [[Old Norse]] ''[[draugr]]'', which literally means a spirit who guards the burial mound of a king. How this image of a vengeful guardian spirit is related to a fire-breathing serpent is unclear. Many others assume the word ''dragon'' comes from the ancient [[Greek language|Greek]] verb ''derkesthai'', meaning "to see", referring to the dragon's legendarily keen eyesight. In any case, the image of a dragon as a serpent-like creature was already standard at least by the [[8th century]] when ''Beowulf'' was written down. Although today we associate dragons almost universally with fire, in medieval legend the creatures were often associated with water, guarding springs or living near or under water.

| + | Dragons are not very common in [[Basque]] legend, however due to such writers as [[Chao]] and [[Juan Delmas]]' interest in the creatures, the ''[[Herensuge]],'' meaning the "third" or "last serpent," has been preserved for today's readers. An [[evil]] [[spirit]] that took the shape of a serpent, the ''herensuge'' would terrorize local towns, killing livestock, and misleading people. The best known legend has [[Archangel Michael|St. Michael]] descending from [[Heaven]] to kill it but only once [[God]] accepted to accompany him in person. [[Sugaar]], the Basque male god, whose name can be read as "male serpent,"<ref>Buber's Basque Page, [http://www.buber.net/Basque/Folklore/aunamendi.herensuge.php "Basque Mythology:Herensuge"] (2005). Retrieved April 15, 2007.</ref> is often associated with the serpent or dragon, but able to take other forms as well. |

| − | [[Image:stgeorge-dragon.jpg|thumb|[[Saint George]] versus the dragon]] | |

| − | Other European legends about dragons include "[[Saint George and the Dragon]]", in which a brave [[knight]] defeats a dragon holding a [[prince]]ss captive. This legend may be a [[Christianity|Christianized]] version of the myth of [[Perseus (mythology)|Perseus]], or of the mounted Phrygian god [[Sabazios]] vanquishing the [[chthonic]] serpent, but its origins are obscure.

| |

| | | | |

| − | The tale of George and the Dragon has been modified for modern works, with Saint George portrayed in one Welsh nationalist rendering as ''an effete wally who faints at the sight of the dragon'' [http://fp.millennas.f9.co.uk/clerchr3.htm] and a poem by [[U. A. Fanthorpe]] based on [[Paolo Uccello]]'s painting, which hangs in the British [[National Gallery, London|National Gallery]]. In the poem, Saint George is a thug, the Maiden considers the relative sexual merits of the dragon and saint, and the Dragon is the only sane character. Certainly, Uccello's fifteenth-century painting, in which the Maiden has the dragon on a leash, is itself not the most conventional representation of the story.

| + | ===Italian mythology=== |

| | | | |

| − | It is possible that the dragon legends of northwestern Europe are at least partly inspired by earlier stories from the [[Roman Empire]], or from the [[Sarmatians]] and related cultures north of the [[Black Sea]]. There has also been speculation that dragon mythology might have originated from stories of large land [[lizard]]s which inhabited [[Eurasia]], or that the sight of giant fossil bones eroding from the earth may have inspired dragon myths (compare [[Griffin]]).

| + | The [[legend]] of [[Saint George]] and the dragon is well known in [[Italy]]. But other [[saint]]s are depicted fighting a dragon. For instance, the first bishop of the city of [[Forlì]], named [[Saint Mercurialis]], was said to have killed a dragon and saved Forlì. Likewise, the first patron saint of [[Venice]], [[Theodore of Amasea|Saint Theodore of Tyro]], was a dragon-slayer, and a statue representing his slaying of the dragon still tops one of the two columns in [[St. Mark's]] square. |

| | | | |

| − | The Germanic tribe, the [[Anglo Saxons]], under the warriors [[Hengest]] and [[Horsa]] broght the symbol of the [[White Dragon (England)|White Dragon]] to [[England]] in the [[United Kingdom]]. Today, the White Dragon is representative of England. | + | ===Christianity=== |

| | + | [[Image:reddragon.jpg|thumb|200 px|''The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in Sun'' William Blake]] |

| | + | In the [[Bible]], there are no direct references to dragons, but there are some creatures that seem to fit the description. In the [[Book of Job]] Chapter 41, the sea monster [[Leviathan]] has some resemblance to a dragon. Most prominent, though, is [[Book of Revelation|Revelation]] 12:3, where an enormous red beast with seven heads is described, whose tail sweeps one third of the stars from heaven down to earth. In most translations, the word "dragon" is used to describe the beast, since in the original [[Greek language|Greek]] the word used is ''drakon'' (δράκον). |

| | | | |

| − | ===Dragons in Celtic mythology===

| + | The Medieval Church's interpretation of the [[Devil]] being associated with the serpent who tempted [[Adam and Eve]] gave a snake-like dragon connotations of [[evil]]. The [[demon]]ic opponents of [[God]], [[Christ]], or good [[Christian]]s have commonly been portrayed as [[reptile|reptilian]] or [[Chimera (mythology)|chimeric]]. The dragon, because it horded [[gold]] and treasure, and lived underground in lore, thus also became a [[symbol]] of [[sin]], particularly how [[greed]] could consume a person to the point of becoming dragon-like. Around the same time, in [[Catholic]] [[literature]] and [[iconography]], some saints were depicted in the act of killing a dragon. This became a prevalent scene, not just for saints but for Christian knights, who must kill or destroy sin, vanquishing evil, in order to save the righteous. |

| | | | |

| − | [[Image:Flag of Wales 2.svg|thumb|right|The [[flag of Wales|Welsh flag]], showing a red dragon passant]]

| + | ==Literature and fiction== |

| − | However, the dragon is now more commonly associated with [[Wales]] due to the national flag having a red dragon (''[[Y Ddraig Goch]]'') as its emblem and their national [[Rugby union in Wales|rugby union]] and [[Rugby league in Wales|rugby league]] teams are known as the dragons. An ancient story in Britain tells of a white dragon and a red dragon fighting to the death, with the red dragon being the resounding victor. The red dragon is linked with the [[Brython|Britons]] who are today represented by the Welsh and it is believed that the white dragon refers to the [[Saxons]] - now the [[England|English]] - who invaded southern [[Britain]] in the 5th and 6th centuries. Some have speculated that it originates from [[Arthurian Legend]] where [[Merlin (wizard)|Merlin]] had a vision of the red dragon (representing [[Vortigern]]) and the white dragon (representing the invading Saxons) in battle. That particular legend also features in the [[Mabinogion]] in the story of ''Llud and Llevelys''.

| |

| | | | |

| − | It has also been speculated that the red dragon of Wales may have originated in the Sarmatian-influenced [[Dacian Draco|Draco]] standards carried by Late Roman cavalry, who would have been the primary defence against the Saxons. In [[Cymric language]] the word "ddraich" means also a chieftain, apparently due to the Roman ''draco'' standards.

| + | Dragons have been portrayed in numerous works of [[literature]]. From the classics, some of the most famous examples include the Old English epic ''[[Beowulf]],'' which ends with the [[hero]] battling a dragon; and [[Edmund Spenser]]'s ''[[The Faerie Queen]],'' where dragon creatures appear regularly. The story of [[Saint George]] slaying the dragon was incorporated into [[fairy tale]]s at some point, a princess being held captive by a dragon becoming an almost clichéd theme. |

| | | | |

| − | The Welsh flag is ''parti per fess Argent and Vert; a dragon Gules passant''.

| + | Most of these representations of dragons were negative—more often they were a supernatural element for a hero to overcome in order to achieve his goals. Some later [[fantasy]] writers, such as [[J.R.R. Tolken]] kept this view of dragons with his character Smaug, a greedy dragon who is brought down by his own pride in ''The Hobbit.'' However, in the twentieth century, some fantasy writers started to shift away from this view. Several writers, such as [[Anne McCaffrey]], started to explore a kinship between humans and dragons, somewhat resembling that between [[horse]]s and humans (although the dragons were generally more intelligent and could often talk). |

| | | | |

| − | ===Dragons in Basque mythology===

| + | Additionally, some [[Christian]] authors have said that dragons were good, before they [[Fall of Man|fell from grace]], as humans did from the [[Garden of Eden]] after [[Adam and Eve]] committed the [[Original Sin]]. Also contributing to the good dragon argument in Christianity is the fact that, if they did exist, they were created by [[God]] as were all creatures. An example of this type of thinking is seen in ''Dragons In Our Midst,'' a Christian book series by author Bryan Davis. |

| | | | |

| − | [[Herensuge]] is the name given to the dragon in [[Basque mythology]], meaning apparently the "third" or "last serpent". The best known legend has [[Archangel Michael|St. Michael]] descending from [[Heaven]] to kill it but only once [[God]] accepted to accompany him in person.

| + | Also helping to change how dragons are viewed were movies such as ''Dragonheart'' (1996), that, although also given a [[medieval]] context, generally depicted dragons as good beings who in fact often saved the lives of humans. Dragons have also been portrayed as friends of children, as in the song and poem ''Puff the Magic Dragon.'' Thus, dragons are no longer automatically viewed as manifestations of evil, beasts that must be defeated by heroes in order to fulfill their mission, but can be seen in a vast range of roles, from companions and friends of humans, to keepers of knowledge and power. |

| | | | |

| − | [[Sugaar]], the Basque male god, is often associated with the serpent or dragon but able to take other forms as well. His name can be read as "male serpent". | + | ==Heraldry== |

| | + | [[Image:Flag of Wales 2.svg|thumb|250 px|right|The Welsh flag, showing a red dragon passant]] |

| | + | The dragon and dragon-like creatures are depicted fairly often in [[heraldry]] throughout [[Europe]], but most notably in [[Great Britain]] and [[Germany]]. ''Wyverns,'' dragons with two back legs and two frontal wings, are the most common, depicting strength and protection, but may also symbolize vengeance. The typical dragon, with wings and four legs, is the second most popular symbol, representing wealth and power. |

| | | | |

| − | [[Agustin Xaho|A. Xaho]], a romantic myth creator of the 19th century, fused these myths in his own creation of ''Leherensuge'', the first and last serpent, that in his newly coined legend would arise again some time in the future bringing the rebirth of the [[Basque people|Basque nation]].

| + | In Britain, these types of images were made famous by [[King Arthur]]'s father [[Uther Pendragon]] who had a dragon on his crest, and also by the story of [[Saint George]] and the dragon. It can be noted that even though images of dragons in heraldry could be positive, this did not change the overall negative attitude towards the dragon in Europe.<ref>Kylie McCormick, [http://www.blackdrago.com/heraldic.htm "Dragons in Heraldry"] (2004). Retrieved April 15, 2007.</ref> |

| − | | |

| − | ===Dragons in Catalan mythology ===

| |

| − | [[Image:Vibria.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Vibria on Sant Jordi day, taken in [[Barcelona]] ([[Principality of Catalonia|Catalonia]])]]

| |

| − | Dragons are well-known in [[Catalan myths and legends]], in no small part because [[Saint George|St. George]] (Catalan ''Sant Jordi'') is the patron saint of [[Principality of Catalonia|Catalonia]]. Like most dragons, the Catalan dragon (Catalan ''drac'') is basically an enormous serpent with two legs, or, rarely, four, and sometimes a pair of wings. As in many other parts of the world, the dragon's face may be like that of some other animal, such as a [[lion]] or [[Cattle|bull]]. As is common elsewhere, Catalan dragons are fire-breathers, and the dragon-fire is all-consuming. Catalan dragons also can emit a fetid odor, which can rot away anything it touches.

| |

| − | | |

| − | The Catalans also distinguish a ''víbria'' or ''vibra'' (cognate with English ''[[viper]]'' and ''[[wyvern]]''), a female dragon with two prominent breasts, two claws and an [[eagle]]'s beak.

| |

| − | | |

| − | === Dragons in Italian mythology ===

| |

| − | | |

| − | The legend of [[Saint George]] and the dragon is well-known in [[Italy]]. But other Saints are depicted fighting a dragon. For instance, the first bishop of the city of [[Forlì]], named [[Saint Mercurialis]], was said to have killed a dragon and saved Forlì. So he often is depicted in the act of killing a dragon. Likewise, the first patron saint of [[Venice]], [[Theodore of Amasea|Saint Theodore of Tyro]], was a dragon-slayer, and a statue representing his slaying of the dragon still tops one of the two columns in [[St. Mark's ]] square.

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Dragons in world mythology==

| |

| − | <div align="center">

| |

| − | <gallery>

| |

| − | Image:Marduk and pet.jpg|The ancient [[Mesopotamia]]n god [[Marduk]] and his dragon, from a [[Babylonia]]n cylinder seal

| |

| − | Image:Pergamonmuseum_Ishtartor_02.jpg|Oldest known picture of a "dragon" (Ishtar Gate)

| |

| − | Image:Paolo Uccello 050.jpg|[[Saint George]] slaying the dragon, as depicted by [[Paolo Uccello]], c. 1470

| |

| − | Image:Stockholm-Gamla Stan-6.jpg| St. George and the dragon in Stockholm

| |

| − | </gallery>

| |

| − | </div>

| |

| − | | |

| − | {| class="wikitable"

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="4" style="background-color: #ffa; text-align: center; font-weight: bold;" | [[Chinese dragon|Asian dragon]]s

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | [[Chinese dragon]]

| |

| − | | '''Lung'''

| |

| − | | Lung have a long, scaled serpentine form combined with the attributes of other animals; most (but not all) are wingless, and has four claws on each foot (five for the imperial emblem). They are rulers of the weather and water, and a symbol of power.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | [[Japanese dragon]]

| |

| − | | '''Ryū'''

| |

| − | | Similar to Chinese and Korean dragons, with three claws instead of four. They are benevolent (with exceptions) and may grant wishes; rare in Japanese mythology.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | [[Vietnamese dragon]]

| |

| − | | '''Rồng''' or '''Long'''

| |

| − | | These dragons' bodies curve lithely, in [[sine]] shape, with 12 sections, symbolising 12 months in the year. They are able to change the weather, and are responsible for crops. On the dragon's back are little, uninterrupted, regular fins. The head has a long mane, beard, prominent eyes, crest on nose, but no horns. The jaw is large and opened, with a long, thin tongue; they always keep a châu (gem/jewel) in their mouths (a symbol of humanity, nobility and knowledge).

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | rowspan="3" | [[Korean dragon]]

| |

| − | | '''Yong'''

| |

| − | | A sky dragon, essentially the same as the Chinese lóng. Like the lóng, yong and the other Korean dragons are associated with water and weather.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | '''yo'''

| |

| − | | A hornless ocean dragon, sometimes equated with a [[sea serpent]].

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | '''kyo'''

| |

| − | | A mountain dragon.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | |[[Siberian dragon]]

| |

| − | | '''[[Yilbegan]]'''

| |

| − | | Related to European Turkic and Slavic dragons

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | |Indian Dragon

| |

| − | |'''Vyalee'''

| |

| − | |Usually seen in temples of South India

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="4" style="background-color: #ffa; text-align: center; font-weight: bold;" | [[European dragon]]s

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Scandinavian & Germanic dragons

| |

| − | | '''[[lindworm]]'''

| |

| − | | A very large winged or wingless serpent with two or no legs, the lindworm is really closer to a [[wyvern]]. They were believed to eat cattle and symbolized pestilence. On the other hand, seeing one was considered good luck. The dragon [[Fafnir]], killed by the legendary hero [[Sigurd]], was called an ormr ('worm') in Old Norse and was in effect a giant snake; it neither flew nor breathed fire. The dragon killed by the Old English hero [[Beowulf]], on the other hand, did fly and breathe fire. Marco Polo encountered one on his journey.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Welsh dragon

| |

| − | | '''[[Y Ddraig Goch]]'''

| |

| − | | The red dragon is the traditional symbol of Wales and appears on the Welsh national flag.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | rowspan="3" | Hungarian dragons (Sárkányok)

| |

| − | | '''[[zomok]]'''

| |

| − | | A great snake living in swamp, which regularly kills pigs or sheeps. A group of sheperds can easily kill them.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | '''[[sárkánykígyó]]'''

| |

| − | | A giant winged snake, which in fact a full-grown ''zomok''. It often serves as flying mount of the ''garabonciások'' (a kind of magicians). The sárkánykígyó rules over storms and bad weather.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | '''[[sárkány]]'''

| |

| − | | A kind of human form dragon. Most of them are giants with multiple heads. Their strength is held in their heads. They become gradually weaker as they lose their heads.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | [[Slavic dragon]]s

| |

| − | | '''zmey''', '''zmiy''', or '''zmaj'''

| |

| − | | Similar to the conventional European dragon, but multi-headed. They breathe fire and/or leave fiery wakes as they fly. In Slavic and related tradition, dragons symbolize evil. Specific dragons are often given [[Turkic languages|Turkic]] names (see Zilant, below), symbolizing the long-standing conflict between the Slavs and Turks.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Romanian dragons

| |

| − | | '''[[balaur]]'''

| |

| − | | Balaur are very similar to the Slavic zmey: very large, with fins and multiple heads.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | [[Chuvash dragons]]

| |

| − | | '''[[Vere Celen]]'''

| |

| − | |Chuvash dragons represent the pre-Islamic mythology of the same region.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Tatar dragons

| |

| − | | '''[[Zilant]]'''

| |

| − | | Really closer to a [[wyvern]], the Zilant is the symbol of [[Kazan]]. ''Zilant'' itself is a Russian rendering of Tatar ''yılan'', i.e. snake.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | rowspan="2" | Basque dragons

| |

| − | | '''[[Herensuge]]'''

| |

| − | | Basque for Dragon. One legend has [[Archangel Michael|St. Michael]] descending from Heaven to kill it, but only when [[God]] agreed to accompany him, so fearful it was.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | '''[[Sugaar]]'''

| |

| − | | The male god of [[Basque mythology]], also called '''Maju''', was often associated to a serpent or snake, though he can adopt other forms.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="4" style="background-color: #ffa; text-align: center; font-weight: bold;" | American dragons

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Meso-American dragon

| |

| − | | '''[[Mex.amphthere or Am.amphithere]]'''

| |

| − | | Feathered serpent deity responsible for giving knowledge to mankind, and sometimes also a symbol of death and resurrection.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Inca dragon

| |

| − | | Amaru

| |

| − | | A Dragon(sometimes called a snake) on the Inca Culture. The last Inca emperor [[Tupak Amaru]]'s name means "Lord Dragon"

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | '''[[Boi-tata]]'''

| |

| − | | A Dragon-like animal (sometimes like a snake) of the Brazilian indian cultures

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | Chilean dragon

| |

| − | | Caicaivilu and Tentenvilu

| |

| − | | Snake-type dragons, cacaivilu was the sea god and tentenvilu was the earth god, both from the chilean island "Chiloé"

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | |colspan="4" style="background-color: #ffa; text-align: center; font-weight: bold;" | African dragons

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | |African dragon

| |

| − | |'''[[Amphisbaena]]'''

| |

| − | | Possibly originating in northern Africa (and later moving to Greece), this was a two headed dragon (one at the front, and one on the end of its tail). The front head would hold the tail (or neck as the case may be) in its mouth, creating a circle that allowed it to roll.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="4" style="background-color: #ffa; text-align: center; font-weight: bold;" | Dragon-like creatures

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="2" | '''[[Basilisk]]'''

| |

| − | | A basilisk is hatched by a cockerel from a serpent's egg. It is a lizard-like or snake-like creature that can supposedly kill by its gaze, its voice, or by touching its victim. Like [[Medusa]], a basilisk may be destroyed by seeing itself in a mirror.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="2" | '''[[Leviathan]]'''

| |

| − | | In [[Hebrews|Hebrew]] mythology, a leviathan was a large creature with fierce teeth. Contemporary translations identify the leviathan with the crocodile, but in the [[Bible]], the leviathan can breathe fire (Job 41:18-21), can fly (Job 41:5), and cannot be pierced with spears or harpoons (Job 41:7), his scales so close that there is no room between them (Job 41:15-16), his upright walk (Job 41:12), his teeth close together (Job 41:14), an underbelly that could cut you(Job 41:30) so the identification does not precisely match. Over time, the term came to mean any large sea monster; in [[Hebrew language|modern Hebrew]], "leviathan" simply means whale. A [[sea serpent]] is also closely related to the dragon, though it is more snakelike and lives in the water.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="2" | '''[[Wyvern]]'''

| |

| − | | Much more similar to a dragon than the other creatures listed here, a wyvern is a winged serpent with either two or no legs. The term wyvern is used in [[heraldry]] to distinguish two-legged from four-legged dragons.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | | colspan="2" | '''[[zmeu]]'''

| |

| − | | Derived from the Slavic dragon, zmeu are ''humanoid'' figures that can fly and breathe fire.

| |

| − | |-

| |

| − | |}

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Notable dragons==

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===In myth===

| |

| − | * [[Zahhak|Azhi Dahaka]] was a three-headed demon often characterized as dragon-like in [[Persia]]n [[Zoroastrianism|Zoroastrian]] mythology.

| |

| − | * Similarly, [[Ugaritic]] myth describes a seven-headed [[sea serpent]] named [[Lotan]].

| |

| − | *The [[Lernaean Hydra|Hydra]] of [[Greek mythology]] is a water serpent with multiple heads with mystic powers. When one was chopped off, two would regrow in its place. This creature was vanquished by [[Heracles]] and his cousin.

| |

| − | * [[Smok Wawelski]] was a [[Poland|Polish]] dragon who was supposed to have terrorized the hills around [[Kraków]] in the [[Middle Ages]].

| |

| − | * [[Y Ddraig Goch]] is now the symbol of Wales (see flag, above), originally appearing as the red dragon from the [[Mabinogion]] story ''Lludd and Llevelys''.

| |

| − | * [[Nidhogg]], a dragon in [[Norse]] mythology, was said to live in the darkest part of the [[Underworld]], awaiting [[Ragnarok]]. At that time he would be released to wreak destruction on the world.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===In literature and fiction===

| |

| − | The Old English epic [[Beowulf]] ends with the hero battling a dragon.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Dragons remain fixtures in fantasy books, though portrayals of their nature differ. For example, [[Smaug]], from ''[[The Hobbit]]'' by [[J. R. R. Tolkien]], who is a classic, European-type dragon; deeply magical, he hoards treasure and burns innocent towns.

| |

| − | | |

| − | A common theme in literature concerning dragons is the partnership of Dragon Riding between humans and dragons. This is evident in [[Dragon Rider]] and the [[Inheritance Trilogy]]. Most notably it is featured in [[Anne McCaffrey]]'s ''[[Pern]]'' series; however, "[[Dragons (Pern)|dragons]]" (really genetically modified [[fire-lizard]]s) feature prominently as workhorses, paired with so-called ''dragonriders'' to protect the planet from a deadly threat.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In [[Ursula K. Le Guin]]'s [[Earthsea]] series, the portrayal of dragons undergoes significant changes from book to book.

| |

| − | | |

| − | The dragons in [[Harry Turtledove]]'s [[Harry Turtledove's Darkness|Darkness]] series, a magical analogue of the [[World War II|Second World War]], are beasts, highly pugnacious and under incomplete human control. In the storyline they are the analogue of [[fighter planes]] and dragon riders are obviously intended to represent fighter pilots of the [[Luftwaffe]] and the [[RAF]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | Dragons have been portrayed in several movies of the past few decades, and in many different forms. In ''[[Dragonslayer]]'' (1981), a "sword and sorcerer"-type film set in [[medieval Britain]], a dragon terrorizes a town's population. In contrast, ''[[Dragonheart]]'' (1996), though also given a medieval context, was a much lighter action/adventure movie that spoofed the "terrorizing dragon" stereotype, and depicts dragons as usually good beings, who in fact often save the lives of humans. Dragons can also be passionate protectors, just like the dragoness in ''[[Shrek]]'' and ''[[Shrek 2]]'', who displays her love for a donkey. ''[[Reign of Fire]]'' (2002), also dark and gritty, dealt with the consequences of dormant dragons reawakened in the modern world. | |

| − | | |

| − | Dragons are common (especially as [[non-player characters]]) in ''[[Dungeons & Dragons]]'' and in some [[computer]] [[fantasy]] [[role-playing game]]s. They, like many other dragons in modern culture, run the full range of good, evil, and everything in between.

| |

| − | | |

| − | On the lighter side, ''[[Puff the Magic Dragon]]'' was first a poem, later a song made famous by [[Peter, Paul and Mary]], that has become a pop-culture mainstay. The poem tells of an ageless dragon who befriends a young boy, only to be abandoned as the boy ages and dies.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Some stories give accounts of dragons in human form, notably the fourteenth-century French story Voeux du Paon <ref name=Jones>{{cite book|last=Jones|first=David|title=An Instinct for Dragons|publisher=Routlege|year=2002}}</ref> tells the story of Melusine, a beautiful woman who seemed faithful but refused to take communion in church. When confronted, she turned into a dragon and fled. She has been depicted in Russian art of the 18th century as a woman's head on a dragon's body <ref name=Jones>{{cite book|last=Jones|first=David|title=An Instinct for Dragons|publisher=Routlege|year=2002}}</ref>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===As emblems===

| |

| − | The dragon is the emblem of [[Ljubljana]], [[Slovenia]]. The city has a dragon bridge which is embellished with four dragons. The city's basketball club are nicknamed the "Green Dragons". License plates on cars from the city also feature a dragon.

| |

| | | | |

| | ==Notes== | | ==Notes== |

| − | <!--This article uses the Cite.php citation mechanism. If you would like more information on how to add references to this article, please see http://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Cite/Cite.php —> | + | <references/> |

| − | <div class="references-small">

| |

| − | <references />

| |

| − | </div>

| |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | ==Further reading==

| |

| − | *''Dragons, A Natural History'' by [[Karl Shuker|Dr. Karl Shuker]] Simon & Schuster (1995) ISBN 0-684-81443-9

| |

| − | *''[[The Flight of Dragons]]'' by [[Peter Dickinson]] HarperCollins (1981) ISBN 0-06-011074-0

| |

| − | *''[[Dragonology: The Complete Book of Dragons]]'' by Dugald A. Steer

| |

| − | *''[[A Book of Dragons]]'' by [[Ruth Manning-Sanders]] (a representative collection of dragon [[fairy tales]] from around the world)

| |

| | | | |

| | ==References== | | ==References== |

| − | <references/>

| + | *Campbell, Joseph and Bill Moyers. ''The Power of Myth.'' Anchor, 1991. ISBN 0385418868 |

| − | | + | *Dickinson, Peter. ''The Flight of Dragons.'' Harper Collins, 1981. ISBN 0060110740 |

| − | 3. Littleton, C. Scott. (2002). ''Mythology. The Illustrated Anthology of World Myth and Storytelling.'' London: Duncan Baird.

| + | *Jones, David E. ''An Instinct for Dragons.'' Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0415937299 |

| − | | + | *Manning-Sanders, Ruth. ''A Book of Dragons.'' |

| − | 4. Theosophical University Press. "Encyclopedia Theosophical Glossary Dis – Diz. (1999). '' Dragons''. http://www.theosociety.org/Pasadena.etgloss.dis-diz.htm.

| + | *Nigg, Joe. ''The Book of Dragons & Other Mythical Beasts.'' Barron's Educational Series, 2001. ISBN 978-0764155109 |

| | + | *Nigg, Joe. ''Wonder Beasts: Tales and Lore of the Phoenix, the Griffin, the Unicorn, and the Dragon.'' Libraries Unlimited, 1995. ISBN 156308242X |

| | + | *Shuker, Karl. ''Dragons, A Natural History.'' Simon & Schuster, 1995. ISBN 0684814439 |

| | + | *Steer, Dugald A., and Ernest Drake. ''Dragonology: The Complete Book of Dragons.'' Candlewick, 2003. ISBN 0763623296 |

| | | | |

| | ==External links== | | ==External links== |

| − | *[http://animal.discovery.com/convergence/dragons/index.html Dragons at Animal Planet]

| + | All links retrieved January 30, 2024. |

| − | | |

| − | | |

| − | *[http://www.sommerland.org/ondragons/races/races_european.html European Dragons] - an illustrated European dragon analysis, citing medieval bestiaries and contemporary works.

| |

| − | *[http://www.isidore-of-seville.com/dragons/ Dragons in Art and on the Web], web directory with 1,470 dragon pictures

| |

| − | *[http://www.draconika.com/culture.php Dragons Across Cultures] on draconika.com

| |

| − | *[http://www.colba.net/~tempest/ General Dragon Information and Facts]

| |

| − | *[http://www.theoi.com/Tartaros/Drakones.html "Theoi Project" website: Dragons of classical Greece], excerpts from Greek sources, illustrations, lists and links.

| |

| − | *[http://www.lafura.org/suplements/bestiari/0005.htm A ''víbria'' costume], as worn by a Catalan ''[[geganter]]''.

| |

| − | *[http://www.fectio.org.uk/articles/draco.htm www.fectio.org.uk] - Draco Late Roman military standard

| |

| | | | |

| | + | *[http://www.draconika.com/culture.php Dragons Across Cultures] Draconika.com |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| | {{Credit2|Dragon|91618722|European_dragon|114664892|}} | | {{Credit2|Dragon|91618722|European_dragon|114664892|}} |

Engraving of Ouroboros (a dragon swallowing its own tail) by Lucas Jennis, in alchemical tract titled

De Lapide Philisophico.

- This article focuses on European dragons.

- For dragons in Oriental cultures see Chinese dragon

The dragon is a mythical creature typically depicted as a large and powerful serpent or other reptile with magical or spiritual qualities. Although dragons (or dragon-like creatures) occur commonly in legends around the world, different cultures have perceived them differently. Chinese dragons, and Eastern dragons generally, are usually seen as benevolent and spiritual, representative of primal forces of nature and the universe, and great sources of wisdom. In contrast, European dragons, as well as some cultures of Asia Minor such as the ancient Persian Empire, were more often than not malevolent, associated with evil supernatural forces and the natural enemy of humanity. The most notable exception is the Ouroborus, or the dragon encircling and eating its own tail. When shaped like this the dragon becomes a symbol of eternity, natural cycles, and completion. Dragons are commonly said to possess some form of magic or other supernormal powers, the most famous being the ability to breathe fire from their mouths.

Over the years dragons have become the most famous and recognizable of all mythical creatures, used repeatedly in fantasy, fairy tales, video-games, film, and role-playing games of pop culture fame. While still seen as powerful and often dangerous to humankind, the latter part of the twentieth century saw a change in attitude, with the good qualities of dragons becoming more prominent. No longer must all dragons be defeated by the hero or saint, some are ready to share their wisdom with human beings and act as companions, friends, and even guardians of children—roles that parallel those of the angels.

Etymology

The word "dragon" has etymological roots as far back as ancient Greek, in the verb meaning "to see strong." There were several similar words in contemporary languages of the time that described some form of clear sight, but at some point, the Greek verb was fused with the word for serpent, drakon (δράκον). From there it worked its way to the Latin language, where it was called Draconis, meaning "snake" or "serpent." In the English language, the Latin word was split into several different words, all similar: Dragon became the official name for the large, mythical creatures, while variations on the root, such as "draconian," "draconic," and "draconical" all came to be adjectives describing something old, rigid, out of touch with the world, or even evil.[1]

Description

Dragons generally fit into two categories in European lore: The first has large wings that enable the creature to fly, and it breathes fire from its mouth. The other corresponds more to the image of a giant snake, with no wings but a long, cylindrical body that enables it to slither on the ground. Both of these types are commonly portrayed as reptilian, hatching from eggs, with scaly bodies, and occasionally large eyes. Modern depictions of dragons are very large in size, but some early European depictions of dragons were only the size of bears, or, in some cases, even smaller, around the size of a butterfly. Some dragons were personified to the point that they could speak and felt emotions, while others were merely feral beasts.

Origins

Scholars have attempted to uncover the true source of dragon legends since reports of the ancient creatures themselves have been made public. While it is most probable that dragons in the form popular today never did exist, there is evidence to suggest that perhaps the belief in dragons was based on something real. Some have looked to dinosaurs as the answer.

It is known that ancient cultures, such as the Greeks and Chinese found fossil remains of large creatures they could not easily identify. Such fossils have been held responsible for the creation of other mythical creatures, so it is possible that the belief in dragons could have been fostered in the remains of real animals.

Some take this hypothesis a step further and suggest that dragons are actually a distant memory of real dinosaurs passed down through the generations of humanity. This belief explains why dragons appear in nearly every culture, as well as why the dragon is more closely recognizable as a dinosaur than any other animal.[2] However, such theories disregard the accepted timeline of the Earth's history, with human beings and dinosaurs separated by sixty-five million years, and therefore are disregarded by mainstream scholars. It is more likely that a lack of understanding of nature, certain fossils, a stronger connection with the supernatural, and even perhaps a widespread fear of snakes and reptiles all helped form the idea of the dragon.

Cadmus Sowing the Dragon's teeth, by Maxfield Parrish, 1908

Some of the earliest references to dragons in the west come from Greece. Herodotus, often called the "father of history," visited Judea c.450 B.C.E. and wrote that he heard of dragons, described as small, flying reptile-like creatures. He also wrote that he observed the bones of a large, dragon creature.[3]

The idea of dragons was not unique to Herodotus in Greek mythology. There are many snake or dragon legends, usually in which a serpent or dragon guards some treasure.

The first Pelasgian kings of Athens were said to be half human, half snake. Cadmus slew the water-dragon guardian of the Castalian Spring, and on the instructions of Athena, he sowed the dragon's teeth in the ground, from which there sprang a race of fierce armed men, called Spartes ("sown"), who assisted him to build the citadel of Thebes, becoming the founders of the noblest families of that city. The dragon Ladon guarded the Golden Apples of the Sun of the Hesperides. Another serpentine dragon guarded the Golden Fleece, protecting it from theft by Jason and the Argonauts. Similarly, Pythia and Python, a pair of serpents, guarded the temple of Gaia and the Oracular priestess, before the Delphic Oracle was seized by Apollo and the two serpents were draped around his winged caduceus, which he then gave to Hermes.[4] These stories are not the first to mention dragon-like creatures, but perhaps mark the time in which dragons become popular in Western beliefs, since European culture was so heavily influenced by ancient Greece.