Division of Korea

The division of Korea into North Korea and South Korea stems from the 1945 Allied victory in World War II, ending Japan's 35-year occupation of Korea. The United States and the Soviet Union agreed to temporarily occupy the country as a trusteeship with the zone of control demarcated along the 38th Parallel. The Soviet Union and United States supervised the surrender of Japanese forces in their sectors as well as the establishment a Korean provisional government which would become "free and independent in due course."[1] The Soviet Union refused to participate in the United Nations mandated nationwide democratic election for a new government, leading to a declaration of the Republic of South Korea as the sole legitimate government in Korea.

The Korean War (1950-1953) left the two Koreas separated by the DMZ, remaining technically at war through the Cold War to the present day. North Korea's communist Stalinist and isolationist government has presided over a state-controlled economy dependent upon massive aid from Russia and China to survive. South Korea has developed into one of the world's leading economies, employing free enterprise economic policies as well as fostering a democratic government. Since the 1990s, with progressively liberal South Korean administrations, as well as the death of North Korean founder Kim Il-sung, the two sides have taken small, symbolic steps towards a possible Korean reunification.

|

Jeulmun Period

|

Historical Background

End of World War II (1939–1945)

Main article: World War II

In November 1943, Franklin Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Chiang Kai-shek met at the Cairo Conference to discuss what should happen to Japan's colonies, and agreed that Japan should lose all the territories it had conquered by force because it might become too powerful. In the declaration after that conference, a joint statement mentioned Korea for the first time. The three powers declared that they, "mindful of the enslavement of the people of Korea are determined that in due course Korea shall become free and independent” (Cairo Conference). For some Korean nationalists who wanted immediate independence, the phrase "in due course" caused dismay. Roosevelt may have proposed to Stalin that three or four years elapse before full Korean independence; Stalin demurred, saying that a shorter period of time would be desirable. In any case, discussion of Korea among the Allies waited until imminent victory over Japan.

With the war's end in sight in August 1945, the Allied leaders still lacked consensus on Korea's fate. Many Koreans on the peninsula had made their own plans for the future of Korea, and few of those plans included the re-occupation of Korea by foreign forces. Following the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on August 6th, 1945, Soviet leaders invaded Manchuria, as per Josef Stalin's agreement with Harry Truman during the Potsdam conference.[1] The American leaders worried that the whole peninsula might be occupied by the Soviet Union, and feared this might lead to a Soviet occupation of Japan. Later events showed those fears well founded.

The Soviet forces moved rapidly southward on the Korean peninsula directly toward the United States forces moving northward. On August 10, 1945 two young officers, Dean Rusk and Charles Bonesteel, working on extremely short notice and completely unprepared for the task, seeking to avoid the beginning of World War II between the United States and Soviet Union, hurriedly proposed the 38th parallel as the halting line for the two armies. They used a National Geographic map to decide on the 38th parallel, dividing the country approximately in half while leaving the capital Seoul under American control. They lacked the time to consult experts on Korea. The two men had been unaware that forty years previous, Japan and Russia had discussed sharing Korea along the same parallel. Rusk later said that had he known, he would have chosen a different line. Regardless, the officers forwarded the decision in hastily written into General Order Number One for the administration of postwar Japan. Fortunately, the Soviets agree to the halting line. Some Generals in the Soviet and United States forces preferred to fight what they saw as an inevitable war without delay.

As a colony of Japan, the Korean people had been systematically excluded from important posts in the administration of Korea. General Abe Nobuyuki, the last Japanese Governor-General of Korea, conferred with a number of influential Koreans since the beginning of August 1945 to prepare the hand-over of power. On August 15, 1945, Yo Un Hyong, a moderate left-wing politician, agreed to take over. He took charge of preparing the creation of a new country and worked hard to build governmental structures. On September 6, 1945, a congress of representatives convened in Seoul. The foundation of a modern Korean state took place just three weeks after Japan's capitulation. The government, predominantly left wing, comprised of resistance fighters who agreed with many of communism's views on imperialism and colonialism.

After World War II

In the South

On September 7, 1945, General MacArthur appointed Lieutenant General John R. Hodge to administer Korean affairs, Hodge landing in Incheon with his troops the next day. The "Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea" sent a delegation with three interpreters, but he refused to meet with them.

The American military authorities focused on dealing with Japan's surrender and the repatriation of Japanese to Japan. Little changed in the administration of the country; officials then serving under the Japanese authorities remained in their positions. The United States dismissed the Japanese governor general in until the middle of September, many Japanese officials stayed in office until 1946. Those decisions angered many Koreans since those same Japanese exploited Koreans.

The United States occupation authorities in South Korea faced numerous communist attempts to ferment revoltion during 1945 to 1948 period. The Soviet Union not only put in place a communist dictatorship in the north, it sought to take over control of the south through overthrowing the unstable government in the south. The United States supported Princeton-educated Syngman Rhee, who moved back to Korea after decades of exile in the United States, to provisionally lead the country. Rhee had proven himself a patriot dedicated to democracy and free enterprise. Rhee staunchly countered armed rebellions in the south seeking to overthrow the provisional government and install a Soviet-backed communist dictatorship. To complicate matters, a number of political candidates proclaimed communist allegiance and sympathies, opening attempting to rally support of a communist dictatorship in the south. Clearly, the goal of communists in Korea, north and south, lay in establishing a communist dictatorship on the Korean peninsula. From 1945 to 1950, between 30,000 [2] and 100,000 people would lose their lives in those battles. [3]

In August 1948, the United States supervised a democratic election south of the 38th parallel in compliance with the United Nations mandate for a free and open election in Korea. The Soviet Union refused to allow the northern sector to participate, leading the United Nations to declare Syngman Rhee the legimate president of Korea and the Republic of Korea the sole legimate government on the Korean Peninsula. At that point, the United States withdrew its forces to Japan, leaving South Korea with a police force at best to defend itself. Unfortunately, the United States made public statements that led the North and the Soviet Union to believe the United States took a disinterested stance toward Korea, that the United States would not come to the aid of South Korea if attacked.

In the North

In August 1945 the Soviet Army established the Soviet Civil Authority to rule the country until a domestic regime, friendly to the USSR, could be established. Provisional committees were set up across the country putting Communists into key positions. In March 1946 land reform was instituted as the land from Japanese and collaborator land owners was divided and handed over to poor farmers. Kim Il-sung initiated a sweeping land reform program in 1946. Organizing the many poor civilians and agricultural laborers under the people's committees a nationwide mass campaign broke the control of the old landed classes. Landlords were allowed to keep only the same amount of land as poor civilians who had once rented their land, thereby making for a far more equal distribution of land. The north Korean land reform was achieved in a less violent way than that of China or Vietnam. Official American sources stated, "From all accounts, the former village leaders were eliminated as a political force without resort to bloodshed, but extreme care was take to preclude their return to power."[4] This was very popular with the farmers, but caused many collaborators and former landowners to flee to the south where some of them obtained positions in the new south Korean government. According to the U.S. military government, 400,000 northern Koreans went south as refugees. [5]

Key industries were nationalized. The economic situation was nearly as difficult in the north as it was in the south, as the Japanese had concentrated agriculture in the south and heavy industry in the north.

In February 1946 a provisional government called the North Korean Provisional People's Committee was formed under Kim Il-sung, who had spent the last years of the war training with Soviet troops in Manchuria. Conflicts and power struggles rose up at the top levels of government in Pyongyang as different aspirants maneuvered to gain positions of power in the new government. At the local levels, people's committees openly attacked collaborators and some landlords, confiscating much of their land and possessions. As a consequence many collaborators and others disappeared or were assassinated. It was out in the provinces and by working with these same people's committees that the eventual leader of North Korea, Kim Il-sung, was able to build a grassroots support system that would lift him to power over his political rivals who had stayed in Pyongyang. Soviet forces departed in 1948.

Establishment of two Koreas

With mistrust growing rapidly between the formerly allied United States and Soviet Union, no agreement was reached on how to reconcile the competing provisional governments. The U.S. brought the problem before the United Nations in the fall of 1947. The USSR opposed UN involvement.

The UN passed a resolution on November 14, 1947, declaring that free elections should be held, foreign troops should be withdrawn, and a UN commission for Korea should be created. The Soviet Union, although a member with veto powers, boycotted the voting and did not consider the resolution to be binding.

In April 1948, a conference of organizations from the north and the south met in Pyongyang. This conference produced no results, and the Soviets boycotted the UN-supervised elections in the south. There was no UN supervision of elections in the north. On May 10 the south held elections. Syngman Rhee, who had called for partial elections in the south to consolidate his power as early as 1947, was elected, though left-wing parties boycotted the election. Widespread corruption was reported in the elections and the Republic of Korea began life without a great deal of legitimacy. On August 13, he formally took over power from the U.S. military.

Korean War

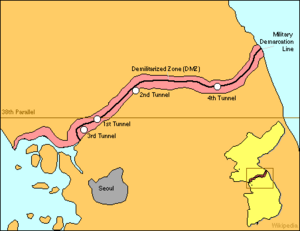

In the North, Democratic People's Republic of Korea was declared on September 9, with Kim Il-sung as prime minister. This division of Korea, after more than a millennium of being unified, was seen as unacceptable and temporary by both regimes. From 1948 until the start of the civil war on June 25, 1950, the armed forces of each side engaged in a series of bloody conflicts along the border. In 1950, these conflicts escalated dramatically when North Korean forces attacked South Korea, triggering the Korean War and effectively making the division permanent. An armistice was signed ending hostilities and the two sides agreed to create a three-mile wide buffer zone between the states, where nobody would enter. This area came to be known as the Demilitarized Zone or DMZ.

After the Korean War (1953–present)

North and South Korea have never signed a formal peace treaty and thus are still officially at war; only a ceasefire was declared. South Korea's government came to be dominated by its military and a relative peace was punctuated by border skirmishes and assassination attempts. The North failed in several assassination attempts on South Korean leaders, most notably in 1968, 1974 and 1983; tunnels were frequently found under the DMZ and war nearly broke out over the axe murder incident at Panmunjeom in 1976. In 1973, extremely secret, high-level contacts began to be conducted through the guise of the Red Cross, but ended after the Panmunjeom incident with little progress having been made.

In the late 1990s, with the South having transitioned to democracy, the success of the Nordpolitik policy, and power in the North having been taken up by Kim Il-sung's son Kim Jong-il, the two nations began to engage publicly for the first time, with the South declaring its Sunshine Policy.

Recently, in effort to promote reconciliation, the two Koreas have adopted an unofficial Unification Flag, representing Korea at international sporting events. The South provides the North with significant aid and cooperative economic ventures, and the two governments have cooperated in organizing meetings of separated family members and limited tourism of North Korean sites. However, the two states still do not recognize each other,[citation needed] and the Sunshine Policy remains controversial in South Korea.

The apportionment of responsibility for the division is much debated, although the older generation of South Koreans generally blame the North's communist zeal for instigating the Korean War.[citation needed] Many in the younger generation see it as a byproduct of the Cold War, criticizing the US role in the establishment of separate states, presence of US troops in the South, and hostile policies against the North.[citation needed]

See also

- History of North Korea

- History of South Korea

- Korean reunification

- Korean Workers Party for information on the formation of North Korea

Notes

- ↑ J. Samuel Walker, "Prompt and Utter Destruction." The University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill.

- ↑ Arthur Millet, The War for Korea, 1945-1950 (2005)

- ↑ Jon Halliday and Bruce Cumings, Korea: The Unknown War, Viking Press, 1988, ISBN 0-670-81903-4

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce. The Origins of the Korean War: Liberation and the Emergence of Separate Regimes, 1945-1947. Princeton University Press, 1981, 607 pages, ISBN 0691093830

- ↑ Allan R. Millet, The War for Korea: 1945-1950 (2005) P. 59

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cho, Soon Sung. 1980. The genesis of tragedy: division of Korea : analysis of American decision-making process. Seoul, Korea: Institute of Foreign Affairs & National Security. OCLC: 40047623

- Cumings, Bruce. 1981. The origins of the Korean War. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691093833

- Hess, Robert Preston. 1960. The background and origins of the thirty-eighth parallel division of Korea. Thesis (M.A.)—Clark University, 1960. OCLC: 37048617

- Kim, Hyung-Kook. 1995. The division of Korea and the alliance making process: internationalization of internal conflict and internalization of international struggle, 1945-1948. Lanham, Md: University Press of America. ISBN 9780819198679

- Lee, Won Sul. 1982. The United States and the division of Korea, 1945. Peace studies book series, no. 2. Seoul: Kyung Hee University Press. OCLC: 8949166

- Oberdorfer, Don. 1997. The two Koreas: a contemporary history. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 9780201409277

External links

- South Korean Ministry of Unification. Retrieved September 11, 2007.

- North Korean News Agency. Retrieved September 11, 2007.

- Korea Web Weekly. Retrieved September 11, 2007.

- NDFSK. Retrieved September 11, 2007.

- Koreascope. Retrieved September 11, 2007.

- Rulers.org. Retrieved September 11, 2007.

[[Category:]]

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.